Abstract

Introduction

Mechanical stimulation is important for maintaining cartilage function. We used a loading device to exert rolling-sliding mechanical stimulation on cartilage preserved in vitro to investigate cartilage viability and the involved mechanisms.

Methods

Osteochondral grafts from pig knees were randomly classified into loading and control groups. The loading group cartilage was subjected to cycles of mechanical stimulation with specified frequency/time/pressure combinations every 3 days; Then the DMEM was refreshed, and the cartilage was preserved in vitro. The control group cartilage was preserved in DMEM throughout the process and was changed every 3 days. On days 14 and 28, the chondrocyte survival rate, histology, and Young’s modulus of the cartilage were measured. Western blots were performed after 2 h of loading to evaluate the protein expression.

Results

The loading group showed a significantly higher chondrocyte survival rate, proteoglycan and type II collagen content, and Young’s modulus than did the control group on day 14, but no statistically significant differences were found on day 28. After two hours of the loading, the phosphorylation levels of MEK and ERK1/2 increased, and the expression of caspase-3, cleaved caspase-3 and bax decreased.

Conclusion

These results suggest that periodic rolling-sliding mechanical stimulation can increase cartilage vitality in 2 weeks; a possible mechanism is that mechanical stimulation activates the MEK/ERK signalling pathway, thus inhibiting apoptotic protein expression. This loading preservation scheme could be used by cartilage tissue banks to improve cartilage preservation in vitro and enhance the quality of cartilage repair.

Keywords: Chondrocyte viability, Mechanical stimulation, Cartilage, Extracellular matrix, ERK

Introduction

Articular cartilage is subjected to continuous mechanical loads under physiological conditions. Biomechanics plays a very important role in the development and pathophysiological process of cartilage.26 Cartilage has no blood vessels, lymphatic tubesor nerve tissue, and its self-repair ability is poor. Osteochondral allograft transplantation (OCT) can be used to repair large-area cartilage defects. There is no reoperation trauma in the donor area, and the effect of long-term clinical treatment is promising for this treatment.30 Before osteochondral tissue transplantation, routine monitoring of microorganisms is needed. Aseptic transport also takes a certain time. Therefore, chondrocyte viability decreases with time during preservation in tissue culture. Improving the viability and prolonging the effective preservation time of transplanted cartilage has become a difficult problem and hot topic. Currently, studies have focused on optimizing the components of the culture medium, exploring preservation temperatures and so on.3,29 The mechanical load regulates the metabolism of chondrocytes and the extracellular matrix (ECM) in complex ways.31 Mechanical forms5,13,21 such as hydrostatic pressure and axial compression, have been applied to chondrocytes with the aim of promoting chondrocyte differentiation and enhancing ECM expression, and various mechanical forms have had different effects on chondrocytes.

Rolling-sliding motion in the knee joint provides a comprehensive load system composed of compression and shear force; however, no studies on rolling-sliding mechanical stimulation of cartilage have been reported yet. Based on the effect of rolling-sliding mechanical stimulation on the growth and development of articular cartilage and preliminary research in this study, we hypothesize that rolling-sliding mechanical stimulation boosts the viability of cartilage preserved in vitro. We applied a bionic-load device that we designed to investigate whether rolling-sliding mechanical stimulation would improve chondrocyte viability, and the involved mechanism was also studied by maintaining ECM content and the mechanical properties of explants during preservation.

Materrials and Methods

Isolation of Osteochondral Explants

Full-thickness osteochondral disks (n = 140) were isolated from the knee joints of eight 1-year-old mature pigs (110 kg) using a specialized osteochondral harvester (Arthrex, CA, USA). The explants were taken from the same anatomical locations in weight-bearing areas of the knee joint, and the loading and control groups have similar properties due to their original adjacent locations. We unified the diameter and thickness of the samples. The diameter of the explants was uniform at 8 mm, and the thickness was 10 mm; the explants contained 2 mm cartilage disks, and the remainder was subchondral bone. This experiment was approved by the Animal Ethics Committee (No. 2017032).

Rolling-Sliding Mechanical Stimulation

We used a rolling-sliding mechanical loading device for the experiment. Osteochondral explants were randomly classified into the loading group and the control group. Explants in the loading group were subjected to cycles of mechanical stimulation every 3 days by the device, and then the specimens were cultured at 4 °C in refreshed serum-free Dulbecco modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM). The culture medium contains 4.5 g/L glucose, penicillin–streptomycin, while lacks sodium pyruvate. The device was operated under aseptic conditions in vitro at 4 °C with a humidity of 40–60%, and it contained culture medium. After parameter screening in preliminary studies, the stimulation protocolwas set as follows: frequency 2 Hz; loading time 30 min/day; and pressure 1.0 MPa. In the control group, cartilage was preserved in culture medium during the whole process at 4 °C, and the culture medium was changed every 3 days.

The loading device (Tsmu-1, Taian, China) was designed by us, and the patent number was CN204579655U. The device consists of a transmission wheel, loading plate, steel roller and so on. Explants were placed aseptically into the holes of the loading plate in the compression chamber containing a modest amount of culture media. The transmission wheel, which connected the slide bar frame, was driven by the speed motor, pushing the stainless-steel roller (located underneath) back and forth, thus exerting rolling-sliding mechanical compression on the cartilage (Fig. 1). It is a load-control scheme. The step motor control system can regulate frequency and loading time. Pressure can be controlled by the load control module. This scheme generates dynamic compression and shear force on the explants. The deformation causes internal fluid flow, and chondrocyte are subjected to compound forms of compression and fluid shear force. The loading device provides a complex bionic mechanical environment for cartilage. Control explants were placed in another plate of the chamber with media without mechanical stimulation so that they experienced identical conditions to the loaded specimens. After loading, all the explants were transferred to the culture medium.

Figure 1.

Schematic of the loading device, which primarily consists of a transmission wheel, loading plate, steel roller and so on. The device provides an environment that contains culture medium and applies bionic rolling-sliding mechanical stimulation to osteochondral tissues. The explants are placed aseptically into the holes of the loading plate in a compression chamber. The transmission wheel that connected the slide bar frame is driven by the speed motor, pushing the stainless-steel roller underneath in a back and forth motion, thus exerting mechanical stimulation on the cartilage.

On days 14 and 28, the chondrocyte survival rate, histology, and Young’s modulus of the cartilage were measured to observe consequent load-induced tissue vitality changes. After loading, the expression of related protein was also tested.

Determination of Chondrocyte Viability

We removed the subchondral bone and kept the cartilage (n = 10) located above it, and then rinsed the cartilage with phosphate buffer saline (PBS). A 40-μm-thick slice was made from specimens with a vibratome (VT1000, Laica, Barnack, Oskar, Germany). The slices were stained with 50 mg/L fluorescein diacetate (FDA, Solarbio) and 10 mg/L ethidium bromide (EB, Sigma). Dual-colour fluorescence indicated chondrocyte viability; Cells with green fluorescence were considered live, whereas cells with red or orange fluorescence were considered dead. The cartilage stained with FDA/EB was incubated at 37 °C for 30 min. Slices were then observed under a fluorescence microscope (ECLIPSE-80I, Nikon, Tokyo, Japan), and images were analysed by Image-Pro Plus 6.0 software (MediaCybernetics, MD, USA) to count different cells. The chondrocyte survival rate was calculated according to the percentage of live cells in total cells.

Histological Analysis

Cartilages specimens (n = 10) were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (Sigma) for 24 h and decalcified in 10% EDTA (Sigma) for 2 weeks. Then, the samples were embedded in paraffin, and sectioned at 5-μm thickness. The morphology of the cartilage was tested by HE staining, the distribution of proteoglycans (PG) was detected using safranin O-fast green and toluidine blue staining, and type II collagen was detected by immunohistochemical staining as previously described.9,10 Stained samples were observed under the microscope (ECLIPSE-80I, Nikon, Tokyo, Japan) and photographed. Eight random non-overlapping fields of view were observed for each sample. Contents of PG and type II collagen were measured by calculating the integrated optical density (IOD) with Image-Pro Plus 6.0 software as previously described.29 The IOD value depends on the positive staining areas and is proportional to the amout of PG or collagen II.

Biomechanical Characterization of the Explants

The subchondral bone was removed carefully. The biomechanical properties of the specimens (n = 10) were measured by an axial compression test using amechanical tester (3340, Instron, Norwood, MA, USA) at room temperature, and cartilage disks were kept moist with PBS during the test. The precompression force was set with the software, which then started to record the displacement, load and time. We set the compression speed to 0.1 mm/s at a maximum force of 100 N, and the compression strain was fifteen percent. When the compressive stress-strain curve became stable, the Young’s modulus was calculated by native software.

Western Blot Analysis

Total protein in both groups was extracted in RIPA buffer at room temperature after two hours of the loading experiment. The lysates were collected and centrifuged at 15,000 rpm with a microcentrifuge. The cellular extracts were separated by 10% SDS-PAGE and then electrotransferred onto polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF, Gibco, MA, USA) membranes. The membranes were blocked with 3% non-fat milk for 1 h in TBS-T. The membranes were rinsed twice with TBS-T and incubated with the antibodies p-MEK (ab4750, Abcam, Cambridge, UK), antibodies MEK (ab178876, Abcam, Cambridge, UK), p-ERK1/2 (ab201015, Abcam, Cambridge, UK), ERK1/2 (ab79853, Abcam, Cambridge, UK), caspase-3 (sc-373730, Santa Cruz, CA, USA), cleaved caspase-3 (ab2302, Abcam, Cambridge, UK) and bax (sc-20067, Santa Cruz, CA, USA) overnight at 4 °C. The membranes were washed and incubated with the related anti-mouse or anti-rabbit HRP-conjugated IgG antibodies (sc-516102 sc-2357, Santa Cruz, CA, USA) for 1 h. An anti-GAPDH antibody (ab8245, Abcam, Cambridge, UK) was used as a control. Then, the protein bands were detected.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed by SPSS 18.0 software (IBM, Armonk, NY). Experimental data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation (SD). Chondrocyte viability, IOD values of histologic staining, Young’s modulus, and relative protein expression were statistically analysed using independent sample t-tests. A level of 5% (p < 0.05) was considered statistically significant for each test.

Results

Chondrocyte Viability

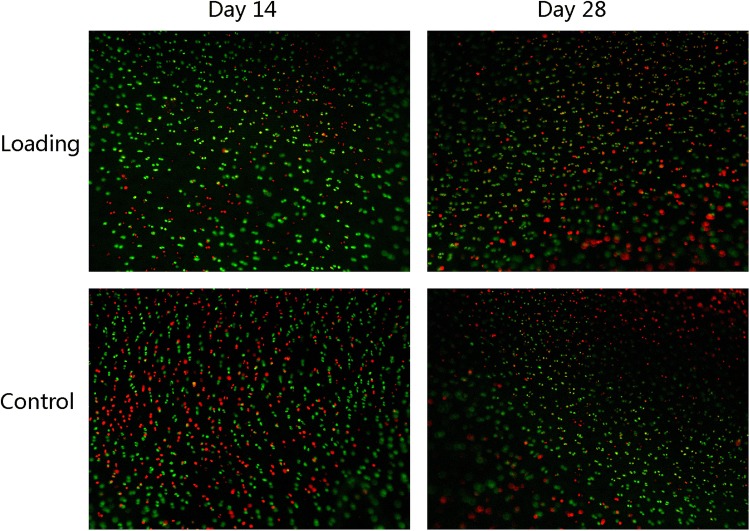

The FDA/EB fluorescence staining in Fig. 2 shows live green and dead red chondrocytes. On day 14, there were more live cells in the loading group, and the chondrocyte survival rate (78.5 ± 1.3%) in the loading group was significantly higher than that in the control group (66.4 ± 1.4%). However, on day 28, the survival rate of the two groups decreased greatly, and the difference was not statistically significant, as is shown in Fig. 3a.

Figure 2.

FDA/EB fluorescence staining of chondrocytes at each time point. Live and dead chondrocytes are indicated by green and red fluorescence, respectively. On day 14, live chondrocyte numbers were higher in the loading group than in the control group. On day 28, there were large numbers of dead chondrocytes in both the groups.

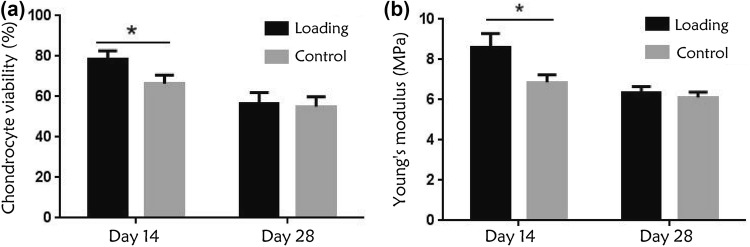

Figure 3.

(a) Chondrocyte survival rate (%) at each time point. On day 14, the chondrocyte survival rate in the loading group was significantly higher than that in the control group. On day 28, the survival rate of the two groups decreased, and the difference was not statistically significant. (b) Young’s modulus of the cartilage. Young’s modulus was significantly higher in the loading group than in the control group on day 14, whereas on day 28, the mechanical properties fell in both the groups, and the difference was not statistically significant. (*p < 0.05).

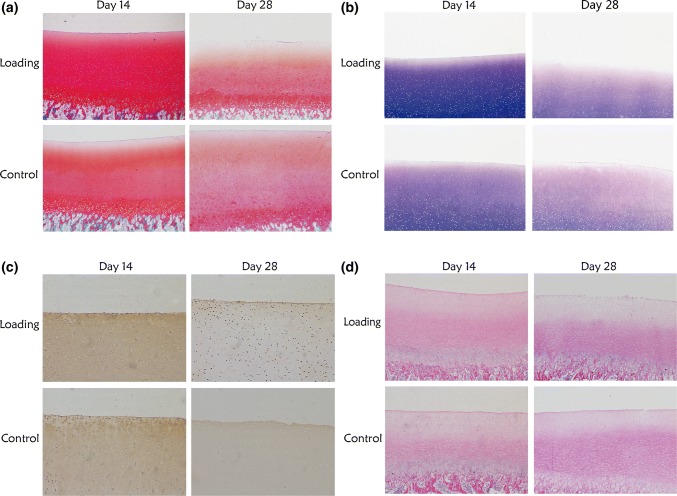

Histology Results

As shown in Fig. 4, on day 14, the cartilage specimens in the loading group had larger amounts of positively stained PG and type II collagen than those in the control group, from the surface to the deep layer. In addition, specimens in the loading group had better morphology than in the static group, with clear levels and rich matrix. On day 28, the content of PG and type II collagen decreased in the two groups, and the surface layer showed the most obvious ECM composition loss. The morphological features of both groups were poor, with obvious loss of chondrocytes and matrix composition.

Figure 4.

Histological staining of cartilage. (a) SafraninO-fast green staining showed the proteoglycan (PG) distribution. On day 14, the content of PG was higher in the loading group than in the control group. On day 28, the content of PG decreased in both groups. (b) toluidine blue staining showed the PG distribution. The content of PG was higher in the loading group than in the control group on day 14, whereas it decreased remarkably in both groups on day 28. (c) immunohistochemical staining showed the type II collagen distribution. On day 14, the type II collagen content was higher in the loading group than in the control group. However, the content significantly decreased in the two groups on day 28. (d) HE staining of cartilage. On day 14, specimens in the loading group has better morphology than those in the control group, with clear levels and rich matrix. On day 28, the morphological features of both the groups were poor, with obvious loss of chondrocytes and matrix composition.

As shown in Fig. 5, the IOD values of safranin O-fast green and toluidine blue and the immunohistochemical staining of cartilage matrix were significantly higher in the loading group than in the control group on day 14. However, on day 28, the IOD values decreased in both groups and were not statistically significant.

Figure 5.

IOD values of histologic staining at different time points. The IOD values of safranin O staining (a), toluidine bluestaining (b) and type II collagen immunohistochemical staining (c) were significantly higher in the loading group than those in the control group on day 14, whereas on day 28, the IOD values decreased and there was no significant difference between the two groups. (*p < 0.05).

Biomechanical Detection

The Young’s modulus of the loading group was higher than that of the static group on day 14, and this difference was statistically significant (p < 0.05). The mechanical properties in the loading group were superior to those in the control group. On day 28, the Young’s modulus decreased in both groups, and there was no significant difference between the two groups (p > 0.05), as shown in Fig. 3b.

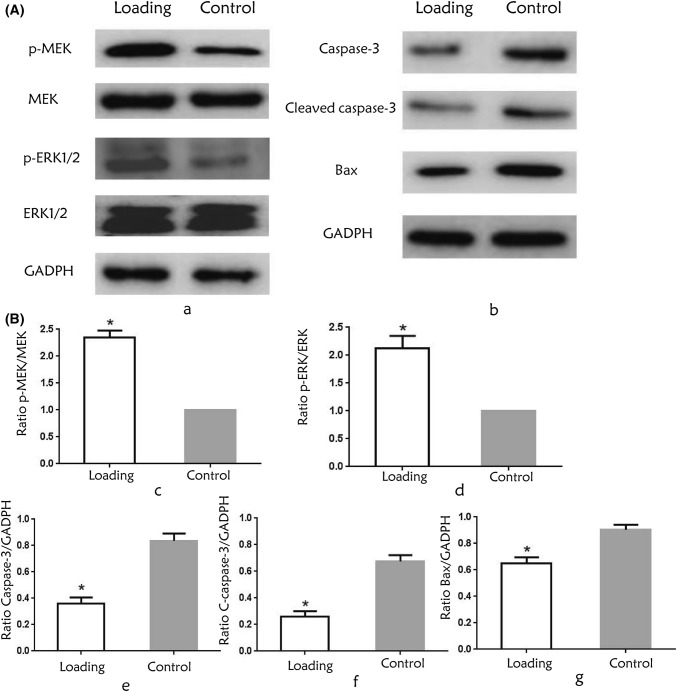

Protein Expression by Western Blot Analysis

After two hours of the mechanical loading, the expression of p-MEK and p-ERK1/2 increased in the loading group (Fig. 6a), and semi-quantitative results showed that the phosphorylation levels of MEK and ERK1/2 increased in the loading group compared to the control group (p < 0.05, Fig. 6b). The expression of apoptosis-related proteins caspase-3, cleaved caspase-3 and bax decreased (Fig. 6a), and there was a significant difference in the relative expression (p < 0.05, Fig. 6b).

Figure 6.

(A) Protein expression after two hours of the loading. (a) The phosphorylation levels of MEK and ERK1/2 in the two groups. (b) The expression of apoptosis-related proteins caspase-3, cleaved caspase-3 and bax decreased after loading. (B) Relative expression of related protein. The ratios of p-MEK/MEK (c), p-ERK/ERK (d) were significantly higher in the loading group, and the ratios of Caspase-3 (e), Cleaved Caspase-3 (f) and Bax (g) to GADPH were significantly lower in the loading group compared to the control group. (*p < 0.05).

Discussion

In this study, we applied rolling-sliding mechanical stimulation precisely to full-thickness cartilage explants containing subchondral bone to investigate the functional and metabolic consequences of loading. In the liquid preservation process in vitro, the mechanical properties of cartilage and chondrocyte viability decreased over time, and we found that cyclic unconfined rolling-sliding compression imposed on articular cartilage was capable of inducing a sequence of changes, including increased chondrocyte viability and mechanical properties and promoted PG and collagen content for days in the loading specimens.

At present, osteochondral allografts are most commonly stored in culture media, such as DMEM, Eagle’s Minimum Essential Medium (EMEM), or other solutions as lactated Ringer’s, RPMI-1640, etc. DMEM is a commonly used culture media that contains basic nutrients capable of supporting cellular viability, such as glucose, amino acids and salts.28,35 The DMEM we used also contained antibiotic. Adding bioactive factors to the culture medium is a hot topic. Bae et al.2 added Epigallocatechin-3-O-gallate (EGCG) to the storage media, and found that chondrocyte viability was significantly well maintained for 2 weeks compared with control group. Chondrocyte viability is critical for cartilage transplantation, generally we consider chondrocyte viability should be at least 70%.6 In our study, we used basal medium and we focused on the role of mechanical stimulation. Chondrocyte viability was > 60% by day 28, combining mechanical stimulation with other methods such as adding bioactive factors is the focus of our further research.

Articular cartilage is stimulated by periodic mechanical loads physiologically. Mechanics regulate the activities of chondrocytes, such as cell migration and differentiation. Mechanical load plays an important role in maintaining the normal function of articular cartilage.19 Chondrocytes are sensitive to abnormal loads, and excessive mechanical disuse can cause cartilage degeneration or even osteoarthritis.37 Bioreactors are applied in tissue engineering cartilage, and they can promote the chondrogenic process by applying mechanical loads to stem cells.4,32 Proper mechanical stimulation has a positive effect on maintaining the phenotype and ECM metabolism of chondrocytes, such as promoting the synthesis of proteoglycans and collagen,7,18 whereas inappropriate mechanical stimulation can lead to changes in chondrocytes, resulting in apoptosis orabnormal matrix metabolism.20 In this study, periodic mechanical intervention was used in the preservation of cartilage tissue in vitro, and the effect of mechanical stimulation on cartilage viability was studied.

A pressure level of 3–5 MPa is common in the knee joint.14 Movement of the knee joint involves two types of motion. One motion is rolling, which represents the rolling of one joint surface on another. The other motion is sliding, which refers to the gliding of one component on another. The point of contact changes in the fixed component when the sliding component moves. These two types of motion coexist during knee joint movement.34 Therefore, we designed a comprehensive rolling-sliding mechanical bioreactor that can simulate the mechanical environments of normal articular cartilage to study the effects of bionic mechanics on cartilage.

Different loading patterns (time/frequency/strength) may affect chondrocyte metabolism.16,36 Research has demonstrated the beneficial effects of physiologic magnitudes of mechanical stimulation on the biochemical properties of chondrocytes. However, raising pressures above these physiologic levels has been shown to have limited or detrimental effects.25 In our study, a pressure of 1.0 MPa showed encouraging results, but the load level we used was much smaller than those found in physiological conditions according to previous research. Cartilage specimens were subjected to cycles of mechanical stimulation every 3 days, and the number of loading cycles performed was moderate. Cycles of mechanical stimulation showed better results than single stimulations.1 Fan et al.8 found that chondrocytes subjected to tensile strain stimulation three times/week for 4 weeks displayed increased proteoglycan content, whereas chondrocytes stimulated daily with the same scheme exhibited negligible effects in terms of ECM accumulation. This finding suggested that the frequency of stimulation needs to be precisely controlled. The cyclic loading regime we used in this study would not produce loss of cell viability or changes that were observable to the naked eye, but they did promote tissue vitality.

Articular cartilage consists of chondrocytes and ECM. Chondrocytes account for 1 to 5% of the total volume of cartilage, and they can synthesize ECM, including collagen and proteoglycans, and regulate matrix metabolism. Chondrocyte viability is one of the gold standards for testing the effect of cartilage preservation in vitro, and chondrocyte viability is also an important criterion for measuring the effect of cartilage repair.27 We found that the survival rate of chondrocytes after the application of mechanical loading in vitro was significantly higher than that in the static group on day 14, and cycles of rolling-sliding mechanical stimulation promoted the viability of chondrocytes. However, on day 28, the survival rate of chondrocytes in the two groups decreased and did not show a significant difference, indicating that the mechanical stimulation scheme failed to maintain chondrocyte viability for a long time. Studies have shown that compression (50% strain, 3 h/day) exerted on chondrocytes maintained high chondrocyte viability on the first day and increased the expression of type II collagen and proteoglycan in 2 weeks.17 Mechanical stimulation is important for the maintenance of chondrocyte viability.

Histological staining results showed that on day 14, the contents of PG and type II collagen were higher in the loading group than those in the control group, but this phenomenon was not maintained until day 28, and the matrix content decreased; this trend was consistent with chondrocyte viability. Mechanical stimulation altered the metabolism of the cartilage matrix and might have promoted the absorption of culture medium. PG and collagen synthesis were triggered by a series of mechanosensitive cellular responses. Studies have demonstrated that exerting a load on the knee joints of mice lightly for a short time can reduce the activity of matrix metalloproteinase13 (MMP-13), which can induce matrix degradation, thus protecting articular cartilage.12

ECM is the basis of the biomechanical properties of cartilage. Cartilage with good mechanical properties shows good weight-bearing performance. In vivo, the load-bearing function of articular cartilage is mainly for resistance to stress and tension, among which stress resistance is particularly important.11 Articular cartilage is a viscoelastic material, and its Young’s modulus reflects its compressive properties. On day 14, the Young’s modulus of the loading group was significantly higher than that of the control group, showing that the loading group had better biomechanical properties than did the control group. This finding was closely related to the concentration of ECM. On day 28, the Young’s modulus decreased in both groups and did not show a significant difference, which was probably associated with loss of ECM components.

Researchers have elucidated how the pathways underlying mechanical stimulation affect chondrocytes. For example, cellular deformation increases the intracellular concentrations of Ca2+ and Na+ by enhancing ion exchangers and stimulating ion channels.23 The mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPKs) signalling pathway is one of the most important signal transduction systems in organisms, and its subfamilies mainly include ERK1/2, JNK, and p38 MAPK. Extracellular signal regulated kinase 1/2 (extracellular regulated protein kinases, ERK1/2) is an important member of the MAPK family, and the MEK/ERK signalling pathway plays a key role in regulating cell growth, development and apoptosis.22 MEK (mitogen extracellular kinase) regulate the activity of ERK1/2 by phosphorylating threonine and tyrosine residues, and upstream MAPK kinase kinases regulate the activity of MEK by phosphorylation of two serine residues. Then the activated ERK1/2 regulates physiological activity.33 In our study, the mechanical loading increased the phosphorylation of MEK and ERK1/2, and we also found that the expression of apoptosis-related protein caspase-3, cleaved caspase-3 and bax decreased. The mitochondrial pathway is a common mechanism of cell apoptosis. Bax has been reported to translocate from the cytosol to mitochondria, where it causes the release of mitochondrial cytochrome-c, redistributing it prior to processing caspase-3. Caspase-3 is a key executive in the process of apoptosis.15,24 The process of apoptosis was suppressed after loading in our study.

There are some limitations in this study. We used cartilage specimens taken from pigs rather than from humans. Although we unify the sample thickness strictly, the samples could have different mechanical moduli. We mainly detected key proteins in the signal pathway, but pathway inhibitor interventions need to be studied. The duration of mechanically maintained cartilage viability is not long, and functional loading protocols (time/frequency/pressure) must be further studied to understand the potential of rolling-sliding mechanical stimulation and prolong its effective time.

Conclusion

In summary, our results indicate that this cyclic rolling-sliding mechanical stimulation protocol can increase chondrocyte viability, maintain proteoglycan and type II collagen content, and enhance mechanical properties within 14 days when cartilage is preserved in vitro. The mechanism involved may be that mechanical stress promotes cartilage viability partly through the MEK/ERK signalling pathway, thus inhibiting the expression of apoptotic proteins. This loading preservation scheme provides a new idea for cartilage tissue banks that will improve cartilage preservation effects and clinical transplantation.

Acknowledgments

We thank Professor Shan Gao for providing us with the study material. We also thank Professor Cong Cheng, who assisted with the statistical analysis.

Funding

This work was supported by the Shandong Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China [Grant Number ZR2017LH018, Grant No. ZR2013HM034], the Projects of Medical and Health Technology Development Program in Shandong Province [Grant Nos. 2015WS0109; 2013WS0317] and Tai’an Science and Technology Development Plan (Grant No. 2018NS0194).

Conflict of interest

Pengwei Qu, Jianghong Qi, Yunning Han, Lu Zhou, Di Xie, Hongqiang Song, Caiyun Geng, Kaihong Zhang and Guozhu Wang declare they have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Ethical Approval

All animal experiments were carried out in accordance with institutional, national and/or international guidelines and approved by the Experimental Animal Ethics Committee of Shandong First Medical University & Shandong Academy of Medical Science. No human studies were carried out by the authors for this article.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Angele P, Yoo JU, Smith C, et al. Cyclic hydrostatic pressure enhances the chondrogenic phenotype of human mesenchymal progenitor cells differentiated in vitro. J. Orthop. Res. 2003;21(3):451–457. doi: 10.1016/S0736-0266(02)00230-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bae JY, Han DW, Matsumura K, Wakitani S, Nawata M, Hyon SH. Nonfrozen preservation of articular cartilage by epigallocatechin-3-gallate reversibly regulating cell cycle and NF-kappaB expression. Tissue Eng. Part A. 2010;16(2):595–603. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2009.0484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bae JY, Matsumura K, Wakitani S, Kawaguchi A, Tsutsumi S, Hyon SH. Beneficial storage effects of epigallocatechin-3-o-gallate on the articular cartilage of rabbit osteochondral allografts. Cell Transpl. 2009;18(5):505–512. doi: 10.1177/096368970901805-604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carroll SF, Buckley CT, Kelly DJ. Cyclic hydrostatic pressure promotes a stable cartilage phenotype and enhances the functional development of cartilaginous grafts engineered using multipotent stromal cells isolated from bone marrow and infrapatellar fat pad. J. Biomech. 2014;47(9):2115–2121. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2013.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen J, Irianto J, Inamdar S, et al. Cell mechanics, structure, and function are regulated by the stiffness of the three-dimensional microenvironment. Biophys. J. 2012;103(6):1188–1197. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2012.07.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cook JL, Stoker AM, Stannard JP, et al. A novel system improves preservation of osteochondral allografts. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 2014;472(11):3404–3414. doi: 10.1007/s11999-014-3773-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Diao HJ, Fung HS, Yeung P, Lam KL, Yan CH, Chan BP. Dynamic cyclic compression modulates the chondrogenic phenotype in human chondrocytes from late stage osteoarthritis. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2017;486(1):14–21. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2017.02.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fan JC, Waldman SD. The effect of intermittent static biaxial tensile strains on tissue engineered cartilage. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 2010;38(4):1672–1682. doi: 10.1007/s10439-010-9917-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Forriol F, Longo UG, Alvarez E, et al. Scanty integration of osteochondral allografts cryopreserved at low temperatures with dimethyl sulfoxide. Knee Surg. Sports Traumatol. Arthrosc. 2011;19(7):1184–1191. doi: 10.1007/s00167-010-1317-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Glenn RE, Jr, McCarty EC, Potter HG, Juliao SF, Gordon JD, Spindler KP. Comparison of fresh osteochondral autografts and allografts: a canine model. Am. J. Sports Med. 2006;34(7):1084–1093. doi: 10.1177/0363546505284846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Haaparanta AM, Jarvinen E, Cengiz IF, et al. Preparation and characterization of collagen/PLA, chitosan/PLA, and collagen/chitosan/PLA hybrid scaffolds for cartilage tissue engineering. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med. 2014;25(4):1129–1136. doi: 10.1007/s10856-013-5129-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hamamura K, Zhang P, Zhao L, et al. Knee loading reduces MMP13 activity in the mouse cartilage. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2013;14:312. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-14-312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Heyland J, Wiegandt K, Goepfert C, et al. Redifferentiation of chondrocytes and cartilage formation under intermittent hydrostatic pressure. Biotechnol. Lett. 2006;28(20):1641–1648. doi: 10.1007/s10529-006-9144-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hodge WA, Fijan RS, Carlson KL, Burgess RG, Harris WH, Mann RW. Contact pressures in the human hip joint measured in vivo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1986;83(9):2879–2883. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.9.2879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huang T, Zhang H, Wang X, Xu L, Jia J, Zhu X. Gambogenic acid inhibits the proliferation of smallcell lung cancer cells by arresting the cell cycle and inducing apoptosis. Oncol. Rep. 2019;41(3):1700–1706. doi: 10.3892/or.2018.6950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ikenoue T, Trindade MC, Lee MS, et al. Mechanoregulation of human articular chondrocyte aggrecan and type II collagen expression by intermittent hydrostatic pressure in vitro. J. Orthop. Res. 2003;21(1):110–116. doi: 10.1016/S0736-0266(02)00091-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jeon JE, Schrobback K, Hutmacher DW, Klein TJ. Dynamic compression improves biosynthesis of human zonal chondrocytes from osteoarthritis patients. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 2012;20(8):906–915. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2012.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jortikka MO, Parkkinen JJ, Inkinen RI, et al. The role of microtubules in the regulation of proteoglycan synthesis in chondrocytes under hydrostatic pressure. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2000;374(2):172–180. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1999.1543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Juang YM, Lee CY, Hsu WY, Lin CT, Lai CC, Tsai FJ. Proteomic analysis of chondrocytes exposed to pressure. Biomed. Chromatogr. BMC. 2010;24(12):1273–1282. doi: 10.1002/bmc.1436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu Q, Hu X, Zhang X, et al. Effects of mechanical stress on chondrocyte phenotype and chondrocyte extracellular matrix expression. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:37268. doi: 10.1038/srep37268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Madej W, van Caam A, Davidson EN, Hannink G, Buma P, van der Kraan PM. Ageing is associated with reduction of mechanically-induced activation of Smad2/3P signaling in articular cartilage. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2016;24(1):146–157. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2015.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McCubrey JA, Steelman LS, Chappell WH, et al. Roles of the Raf/MEK/ERK pathway in cell growth, malignant transformation and drug resistance. Biochim. et Biophys. acta. 2007;1773(8):1263–1284. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2006.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mizuno S. A novel method for assessing effects of hydrostatic fluid pressure on intracellular calcium: a study with bovine articular chondrocytes. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2005;288(2):C329–C337. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00131.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Murphy KM, Ranganathan V, Farnsworth ML, Kavallaris M, Lock RB. Bcl-2 inhibits Bax translocation from cytosol to mitochondria during drug-induced apoptosis of human tumor cells. Cell Death Differ. 2000;7(1):102–111. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4400597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nakamura S, Arai Y, Takahashi KA, et al. Hydrostatic pressure induces apoptosis of chondrocytes cultured in alginate beads. J. Orthop. Res. 2006;24(4):733–739. doi: 10.1002/jor.20077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nowlan NC, Sharpe J, Roddy KA, Prendergast PJ, Murphy P. Mechanobiology of embryonic skeletal development: insights from animal models. Birth Defects Res. Part C. 2010;90(3):203–213. doi: 10.1002/bdrc.20184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pallante AL, Chen AC, Ball ST, et al. The in vivo performance of osteochondral allografts in the goat is diminished with extended storage and decreased cartilage cellularity. Am. J. Sports Med. 2012;40(8):1814–1823. doi: 10.1177/0363546512449321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pennock AT, Wagner F, Robertson CM, Harwood FL, Bugbee WD, Amiel D. Prolonged storage of osteochondral allografts: does the addition of fetal bovine serum improve chondrocyte viability? J. Knee Surg. 2006;19(4):265–272. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1248117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Qi J, Hu Z, Song H, et al. Cartilage storage at 4 degrees C with regular culture medium replacement benefits chondrocyte viability of osteochondral grafts in vitro. Cell Tissue Bank. 2016;17(3):473–479. doi: 10.1007/s10561-016-9556-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Raz G, Safir OA, Backstein DJ, Lee PT, Gross AE. Distal femoral fresh osteochondral allografts: follow-up at a mean of twenty-two years. J. Bone Joint Surg. 2014;96(13):1101–1107. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.M.00769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Responte DJ, Lee JK, Hu JC, Athanasiou KA. Biomechanics-driven chondrogenesis: from embryo to adult. FASEB J. 2012;26(9):3614–3624. doi: 10.1096/fj.12-207241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shahin K, Doran PM. Tissue engineering of cartilage using a mechanobioreactor exerting simultaneous mechanical shear and compression to simulate the rolling action of articular joints. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2012;109(4):1060–1073. doi: 10.1002/bit.24372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shakibaei M, Schulze-Tanzil G, de Souza P, et al. Inhibition of mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase induces apoptosis of human chondrocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276(16):13289–13294. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M010859200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sun M, Lv D, Zhang C, Zhu L. Culturing functional cartilage tissue under a novel bionic mechanical condition. Med. Hypotheses. 2010;75(6):657–659. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2010.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Teng MS, Yuen AS, Kim HT. Enhancing osteochondral allograft viability: effects of storage media composition. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 2008;466(8):1804–1809. doi: 10.1007/s11999-008-0302-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Weber JF, Waldman SD. Stochastic resonance is a method to improve the biosynthetic response of chondrocytes to mechanical stimulation. J. Orthop. Res. 2016;34(2):231–239. doi: 10.1002/jor.23000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wong M, Carter DR. Articular cartilage functional histomorphology and mechanobiology: a research perspective. Bone. 2003;33(1):1–13. doi: 10.1016/S8756-3282(03)00083-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]