Abstract

Introduction

Fluid shear stress (FSS) is the most common stress produced by mastication, speech, or tooth movement. However, how FSS regulates human periodontal ligament (PDL) cell proliferation and migration as well as the underlying mechanism remains unknown.

Methods

FSS (6 dyn/cm2) was produced in a flow chamber. Cell proliferation was tested by the 5-ethynyl-2′-deoxyuridine assay. Cell migration was tested by the wound healing assay. Gene and protein expression of platelet-derived growth factors (PDGFs) and matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-2 were measured by reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction and western blot analyses.

Results

We investigated the effect of 4 h of 6 dyn/cm2 FSS on proliferation and migration of PDL cells. FSS promoted PDL cell proliferation but inhibited migration. The gene and protein expression of PDGF receptor (PDGFR)-α and β both decreased in response to FSS. Activating and inhibiting the PDGFRs did not affect the FSS-induced increase in cell proliferation. However, activating PDGFRs with PDGF-BB, which bound both PDGFR-α and β, and PDGF-CC and DD, which had high affinities for PDGFR-α and PDGFR-β, individually rescued FSS-inhibited migration. FSS also inhibited MMP-2 gene expression, which was the most important factor for matrix turnover and migration of PDLs. PDGF-BB, CC, and DD increased the FSS-induced decline in MMP-2 expression. These results indicate that MMP-2 is regulated by FSS and contributes to the FSS-induced decrease in cell migration.

Conclusions

Our study suggests a role for PDGFR-α and β in short-term FSS-regulated cell proliferation and migration. These results will help provide the scientific foundation for revealing the mechanisms clinical tooth movement and PDL regeneration.

Keywords: PDGF receptor, Proliferation, Migration, Matrix metalloproteinases-2

Introduction

The periodontal ligament (PDL) is a highly vascular and cellular connective tissue located between the tooth-root cementum and alveolar bone. The PDL supports the teeth in the sockets, senses mechanical stimuli, and transduces stress to the surrounding tissues. The PDL plays an important role in alveolar bone growth, tooth eruption, and tooth movement.15 PDL cells consist of fibroblasts, osteoblasts, osteoclasts, cementoblasts, and their progenitors.26 PDL cells are critical for extracellular matrix (ECM) deposition, tissue remodeling, wound healing, and tissue regeneration.15

The PDL continually senses the mechanical stress produced by mastication, speech, or tooth movement and absorbs that mechanical stress to minimize stress on the tooth. Tooth movement will not occur without the PDL due to ankylosis of the tooth and alveolar bone.23 PDL cells are stimulated by different types of mechanical stress, such as stretch,11 compressive pressure,5 and shear stress.21,25 Shear stress is the main type of stress loaded on the PDL, produced by squeezing of interstitial fluid, which produces fluid shear stress (FSS) around the PDL cells.5,26 FSS regulates proliferation, migration, and differentiation of PDL cells.16,25 However, the underlying mechanism has not been revealed.

Platelet-derived growth factors (PDGFs) and their receptors (PDGFRs) were identified more than four decades ago. They play crucial roles in cell development, growth, migration and are implicated in a range of diseases, including cancers.1 PDGFs, particularly PDGF-BB, have been confirmed to enhance wound healing and regenerate periodontal tissue.22 Nine genes encode PDGF chains, including PDGF-A, B,4 C,6 and D.2 All PDGFs are dimers of disulfide-linked polypeptide chains that interact with PDGFRs.4 PDGFR-α and β are two PDGFRs that form three types of PDGFRs, such as PDGFR-αα, αβ, and ββ. Different receptor dimers form depending on the PDGF ligands.1 PDGF-AA primarily binds with PDGFR-αα. PDGF-AB binds with PDGFR-αα and PDGFR-αβ. PDGF-BB binds all PDGFRs. PDGF-C exhibits a high affinity for PDGFR-α. PDGF-D shows high binding tendencies with PDGFR-β.13 PDGFR-α and PDGFR-β engage several signaling pathways, such as Ras-MAPK (mitogen-activated protein kinase), phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K), and phospholipase C (PLC)-γ. PDGFRs bind with these proteins directly or through adaptor proteins and then activate the molecules.1

Matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) include over 25 zinc-endopeptidases. MMPs digest all components of the ECM, including collagens, fibronectin, laminin, gelatin, and elastin. They play principal roles in tissue remodeling, angiogenesis, and tumor metastasis.14 MMP-2 mainly cleaves collagens I, III, IV, and elastin, gelatin, and fibronectin.26 MMP-2 is regulated by FSS through the PDGF pathway and is involved in cell migration.15 Whether MMP-2 responds to FSS through the PDGF pathway and plays a role in FSS-induced cell migration remains unknown.

We hypothesized that FSS regulated cell proliferation and migration by PDGFRs. The MMP-2 also regulated by PDGFRs. To test this hypothesis, we used primary cultured human PDL cells and flow chamber which produces FSS in our study. We investigated the role of short-term FSS on cell proliferation and migration. FSS (4 h) increased PDL cell proliferation, but decreased cell migration. PDGFR-α and β were both depressed by FSS. Activating or inhibiting the PDGFRs did not affect FSS-induced cell proliferation. Activation of PDGFR-α and/or β obviously increased cell migration. MMP-2 is regulated by FSS by PDGFRs.

Materials and Methods

Isolation and Culture of Human PDL Cells

Human third molars were extracted from healthy young donors (12–28 years) for orthodontic reasons at Peking University Third Hospital, Beijing, China. This study conformed to the Declaration of Helsinki and all procedures were approved by the Beihang University Ethics Committee. PDL cells were obtained and identified as described in our previous study.26 In brief, the middle part of each tooth root was obtained to avoid intermixing gingivae and dental pulp. PDL tissues were cut into pieces and digested with 3 mg/mL collagenase Ι at 37 °C for 40 min. The tissues were centrifuged, and fresh Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) was added (Gibco, Grand Island, NY, USA) with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and penicillin/streptomycin. PDL cells were incubated at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 in air. A 0.25% trypsin solution (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) was used to pass the cells. Immuno-localization indicated that all cells stained positive for vimentin and were negative for cytokeratin. PDL cell passages 3–6 were used in this study. Each experiment included at least two donors.

Mechanical Strain Devices

FSS was produced by a parallel plate flow chamber as described previously.26 The PDL cells were cultured on glass slides until they were 80–90% confluent. The whole device was incubated at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 in air. A 6 dyn/cm2 steady laminar shear flow was loaded on human PDL cells. DMEM with 10% FBS and penicillin/streptomycin was used as the fluid. Different concentrations of PDGF-BB (Peprotech, Rocky Hill, NJ, USA), CC (Peprotech, Rocky Hill, NJ, USA), and DD (R&D Systems, Inc., Minneapolis, MN, USA) added to the medium to activate the PDGF pathway. AG1296 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA) pre-incubated with PDL cells for blocking the PDGFRs.

EdU (5-Ethynyl-2′-deoxyuridine) Staining

The PDL cells were continuously cultured in DMEM with 10% FBS for 16 h after 4 h of FSS loading. A 10 μM EdU solution was added, and the cells were incubated for an additional 4 h. Cells cultured in a static condition were used as a control. After the 20 h incubation, the same concentration of EdU solution was added to the control group cells for 4 h. PDL cells were fixed in 3.7% formaldehyde for 15 min and permeabilized in 0.5% Triton X-100 for 20 min at room temperature. The cells were incubated with the iClick reaction cocktail for 30 min at room temperature following the instructions with the iClick™EdU Andy Fluor 488 Imaging Kit (GeneCopoeia, Rockville, MD, USA). Nuclei were stained with Hoechst 33342. The samples were imaged under a confocal microscope (TCS-SP5; Leica, Solms, Germany). The proliferation results were measured as the ratio of EdU-positive cells to total cells.

Wound Healing Assay

A monolayer of PDL cells cultured on glass slides was scratched in the crossed area with a sterilized pipette tip, and the cells were washed twice with PBS. The cells were loaded with 6 dyn/cm2 FSS for 4 h and cultured for an additional 20 h without FSS. Cells cultured under the same conditions without FSS for 24 h were used as the control. At the each time point, more than three scratched crosses were imaged at the same position by an Olympus IX71 (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). The number of cells in each cross was calculated to estimate cell migration.

Total RNA Extraction and Reverse Transcription-Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-PCR)

PDL cells were harvested, and total RNA was isolated with Trizol reagent (Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY, USA). A 2 μg portion of total RNA was synthesized to cDNA according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Takara, Shiga, Japan). cDNA was used as a template for each PCR amplification. The primer sequences are shown in Table 1. PCR was performed for 32–36 cycles at 94 °C for 30 s, at 58 °C for 30 s, and at 72 °C for 45 s in a DNA thermal cycler. The PCR products underwent 2% agarose gel electrophoresis with ethidium bromide staining. The gray values of the band were analyzed by Bio-Rad Quantity One (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). The PCRs were repeated at least three times.

Table 1.

Primer sequences for RT-PCR.

| Primer names | Sequence (5′–3′) |

|---|---|

| hPDGFR-α | |

| Sense | CGCCAGGCTACCAGGGAGGT |

| Antisense | CAGGAAGCGGCGTGCCTTCA |

| hPDGFR-β | |

| Sense | CTGCGTCTGCAGCACGTGGA |

| Antisense | GCGCTTGTCGGAGTGGTGCT |

| hMMP-2 | |

| Sense | TGCTGGAGACAAATTCTGGAGATAC |

| Antisense | ACTTCACGCTCTTCAGACTTTGG |

| hGAPDH | |

| Sense | GGTCACCAGGGCTGCTTTTA |

| Antisense | AGGTCCTCGCTCTAGGGAG |

Western Blotting

PDL cells that were exposed to an FSS load were solubilized in RIPA lysis buffer on ice for 30 min (Beyotime, Shanghai, China). Phenylmethane sulfonyl fluoride (PMSF) was added to avoid proteolysis. The lysates were centrifuged at 14,000 × g and 4 °C to yield the cell extracts. Equal portions of the cell lysates were separated on 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membranes (Millipore, Bedford, MA, USA). The PVDF membranes were blocked with 5% bovine serum albumin in triethanolamine buffered saline solution (TBS-T) for 1–2 h at room temperature to avoid nonspecific protein binding. The membranes were incubated with primary antibodies to PDGFR-α and β (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA), MMP-2 (Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA) and GAPDH (Hangzhou Goodhere, Hangzhou, China) at 4 °C overnight to identify the specific proteins. The PVDF membranes were washed with TBS-T three times and incubated with a horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibody (Applygen, Beijing, China). Immunoreactive bands were visualized using an enhanced chemiluminescent (ECL) system (Applygen, Beijing, China). Quantity One software was used to analyze the densitometry bands.

Statistical Analysis

Data are presented as means and standard deviations from at least three experiments. Multiple comparisons were analyzed by one-way analysis of variance using SPSS version 19.0 software (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). The least significant difference test was performed as an unpaired comparison for two independent variables. A p value < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

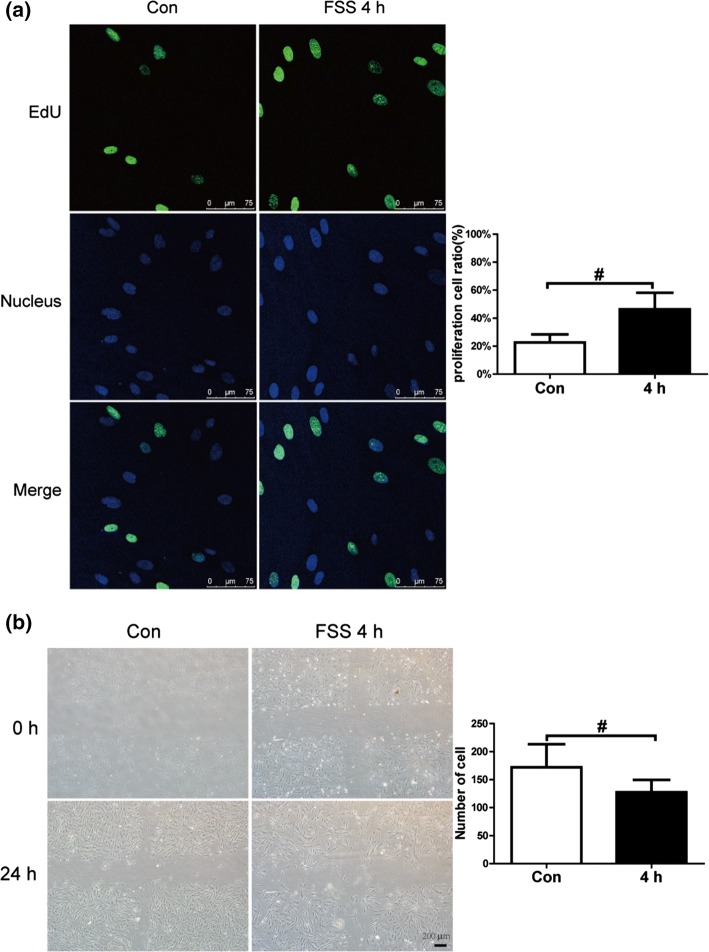

FSS Increases Proliferation but Inhibits Migration of PDL Cells

Our previous study indicated that 3, 6, and 9 dyn/cm2 FSS seemed to affect the expression of MMPs/tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases in PDL cells.26 Long duration FSS, such as 12 or 24 h, inhibited migration and proliferation of PDL cells. Short duration FSS, such as 2 or 4 h, stimulated secretion of growth factors.25 Based on these results, we loaded human PDL cells with 6 dyn/cm2 FSS for 4 h to investigate the effects of short duration FSS on PDL cells. PDL cells cultured under static conditions were used as a control. The PDL cells were imaged to detect the EdU-positive cells after 4 h of FSS and an additional 20 h incubation. The results indicated that FSS increased cell proliferation about twofold (Fig. 1a). The effect of FSS on migration of PDL cells was measured by the wound healing assay. PDL cells were loaded with 4 h of FSS and cultured for an additional 20 h. Cell migration was imaged and the numbers of PDL cells that migrated into the crossed areas were recorded. As results, FSS inhibited migration of the PDL cells compared with the static control group (Fig. 1b).

Figure 1.

A 4 h stimulation with of 6 dyn/cm2 fluid shear stress (FSS) promoted cell proliferation and inhibited migration of periodontal ligament (PDL) cells. A 6 dyn/cm2 FSS treatment was loaded on PDL cells for 4 h. (a) Images of EdU (green)-positive PDL cells represent the control and 4 h FSS groups. Nuclei were stained with Hoechst 33342 (blue). Quantification of the percentage of EdU-positive cells in each group is in the right panel. (b) Wound healing assay images. PDL in the FSS group cells were loaded with 4 h of 6 dyn/cm2 FSS and incubated for an additional 20 h. The control group was incubated under the same conditions without FSS. The same positions in the cross areas were imaged at 0 and 24 h. Cells that migrated into the cross areas were quantified. Data are mean ± standard deviation of at least three experiments (#p < 0.01).

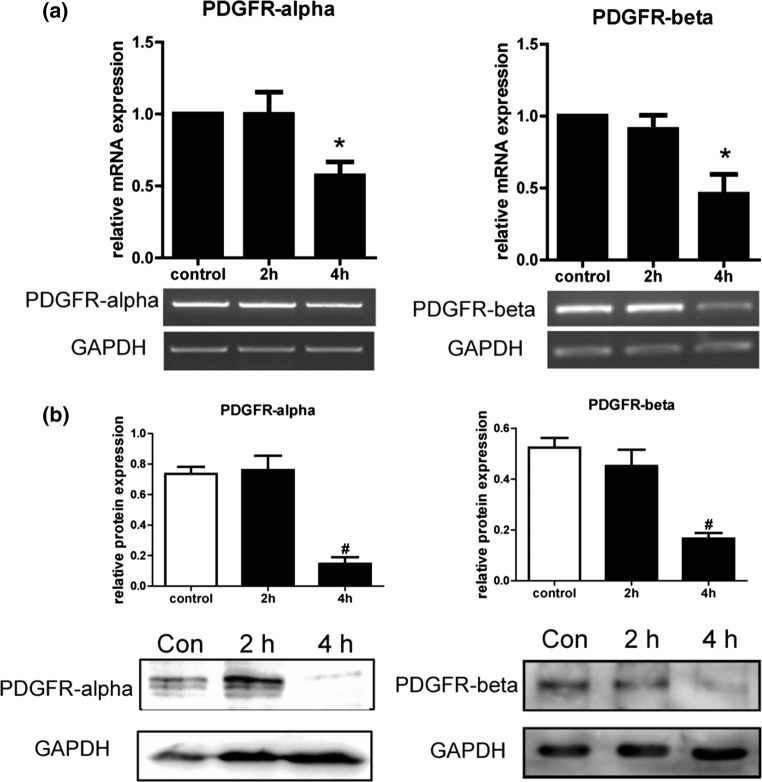

FSS Inhibited PDGFR Expression in PDL Cells

PDL cells were stimulated by 6 dyn/cm2 FSS for 2 and 4 h. Gene expression of PDGFR-α and β was hardly affected after 2 h of FSS but decreased after 4 h of FSS (Fig. 2a). Protein expression coincided with gene expression, as detected by western blot. The 4 h FSS treatment significantly inhibited PDGFR-α and β expression in PDL cells (Fig. 2b), indicating that 4 h of FSS inhibited the PDGFR-α and β gene and protein expression in PDL cells.

Figure 2.

Expression of platelet-derived growth factors (PDGFs) was downregulated by fluid shear stress (FSS). (a) The platelet-derived growth factor receptor (PDGFR)-α and β mRNA levels were quantified by RT-PCR. Relative mRNA expression was normalized to GAPDH expression. Data are mean ± standard deviation of the control in replicated experiments. *p < 0.05 compared with periodontal ligament (PDL) cells without FSS loading. (b) PDGFR-α and β protein levels were quantified by western blot. FSS decreased PDGFR-α and β protein expression. GAPDH protein expression was used as a control.

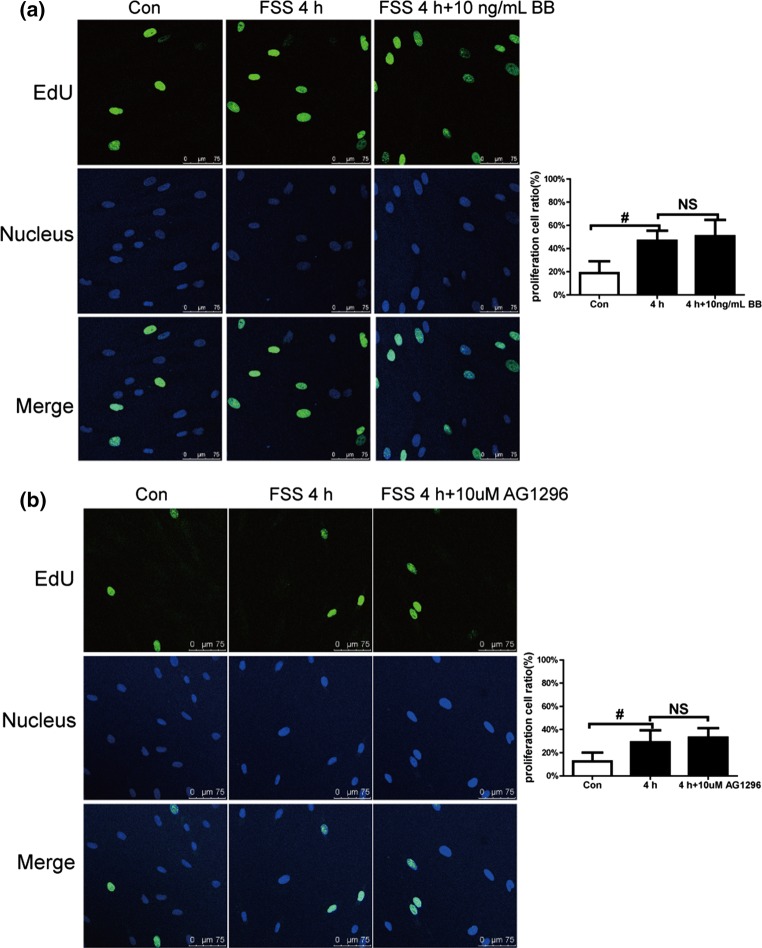

The PDGF Pathway Does Not Regulate FSS-Induced Proliferation of PDL Cells

FSS increased proliferation of PDL cells; thus, we further investigated the role of the PDGF pathway in FSS-regulated proliferation. PDGF-BB (10 ng/mL), which interacts with all PDGFRs, was added to the culture medium and 6 dyn/cm2 FSS was loaded for 4 h. The EdU results demonstrated that PDGF-BB had no significant effect on proliferation (Fig. 3a). Blocking PDGF pathway by 10 µM AG1296 did not affect the PDL cells’ proliferation (Fig. 3b). These results show that either activating or inhibiting the PDGF pathway did change PDL cell proliferation, indicating that the PDGF pathway may not be involved in FSS-induced proliferation of PDL cells.

Figure 3.

Platelet-derived growth factors (PDGFs) did not affect fluid shear stress (FSS)-promoted periodontal ligament (PDL) cell proliferation. Images of EdU-positive PDL cells (green) and nuclei stained with Hoechst 33342 (blue). (a) PDGF-BB (10 ng/mL) did not affect FSS-induced cell proliferation. (b) Inhibiting platelet-derived growth factor receptors (PDGFRs) with AG1296 (10 μm) did not change the FSS-induced increase in cell proliferation. Data are mean ± standard deviation of at least three experiments (#p < 0.01, NS, no significant difference).

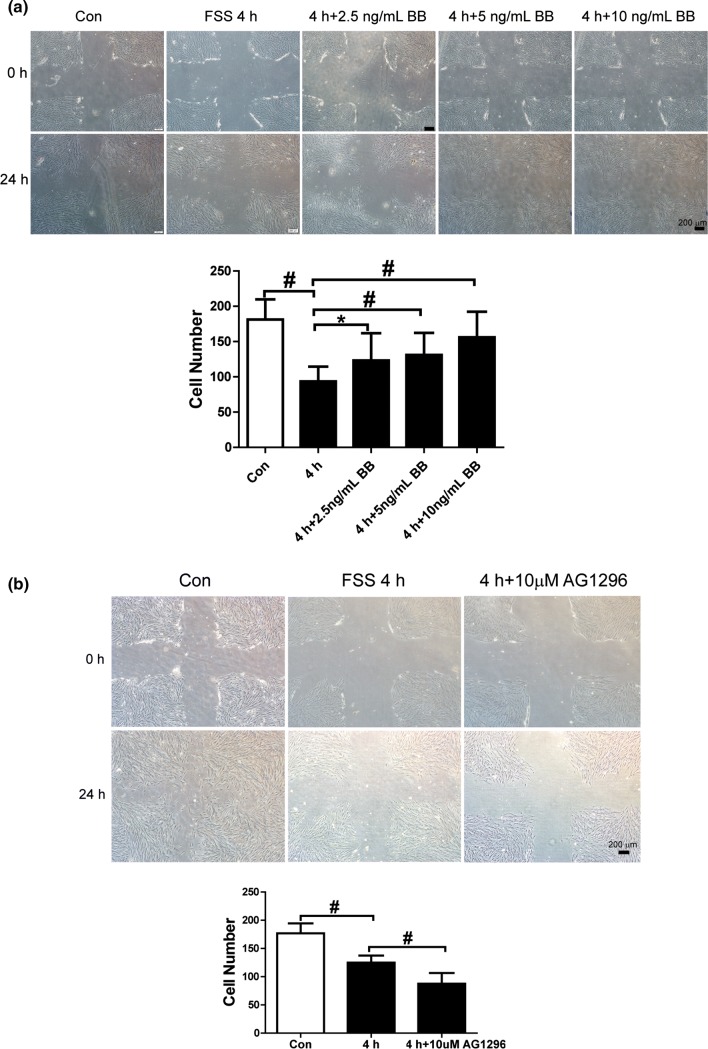

PDGFRs are Involved in FSS-Regulated Migration of PDL Cells

PDGF-BB (2.5, 5, or 10 ng/mL), which activates both PDGFR-α and β, was added to the cultures. The PDL cells were cultured statically or loaded with 6 dyn/cm2 FSS for 4 h as controls. The 4 h of FSS inhibited migration of PDL cells. However, cell migration increased remarkably when 2.5, 5, or 10 ng/mL PDGF-BB was added. The 10 ng/mL PDGF-BB dose was more efficient compared with lower concentrations (Fig. 4a). Cell migration decreased further when PDGFR-α and β were inhibited by AG1296 (Fig. 4b). These results indicate that either activating or inhibiting the PDGF pathway affected FSS-inhibited migration of PDL cells and demonstrates that PDGFRs play a role in FSS-inhibited cell migration.

Figure 4.

PDGFs are involved in FSS-inhibited PDL cell migration. (a) PDGF-BB rescued FSS inhibited cell migration. The wound healing assay was used to investigate cell migration. A 4 h treatment of FSS inhibited cell migration compared with the control. PDGF-BB (2.5, 5, and 10 ng/mL) was added to the culture medium in a flow chamber. Cell migration was rescued when PDGF-BB was combined with 4 h of FSS. PDGF-BB (10 ng/mL) yielded a better effect than 2.5 or 5 ng/mL PDGF-BB. (b) AG1296 (10 μM) which inhibited platelet-derived growth factor receptor (PDGFR) aggravated FSS-induced cell migration. The numbers of cells that migrated into the cross areas were quantified and presented in the panel. Data are mean ± standard deviation of at least three experiments (*p < 0.05, #p < 0.01).

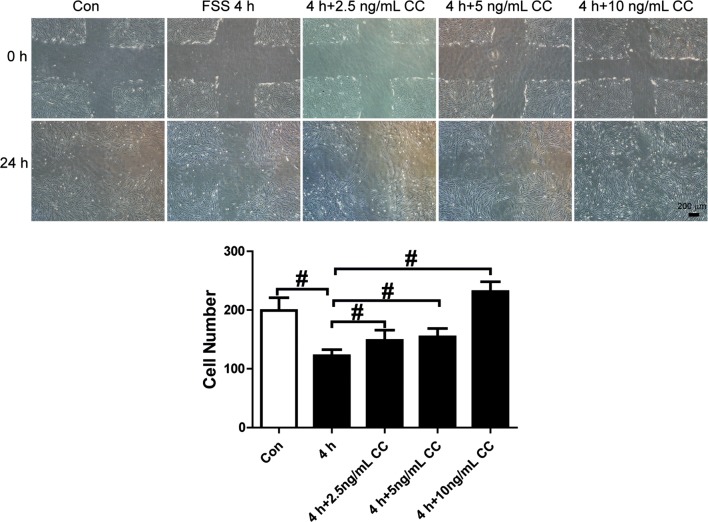

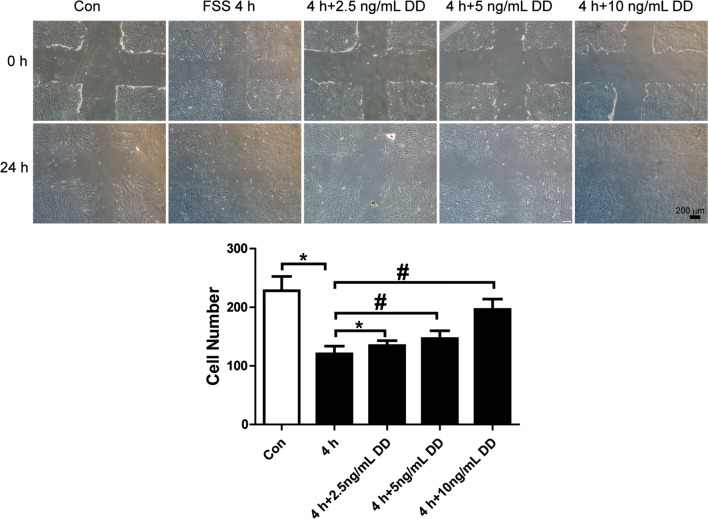

PDGFR-α and β Promote Migration of FSS-Loaded PDL Cells

PDGF-CC and DD were used to activate PDGFR-α or β individually and investigate whether PDGFR-α and β both contributed to FSS-regulated migration of PDL cells. PDGF-CC (2.5, 5, or 10 ng/mL), which activates PDGFR-α, significantly increased cell migration compared with the 4 h FSS group. When the concentration was increased to 10 ng/mL, cell migration increased even higher than that in the static control group (Fig. 5). PDGF-DD (2.5, 5, or 10 ng/mL), which binds with PDGFR-β, promoted FSS-inhibited cell migration. The 10 ng/mL dose of PDGF-DD obviously antagonized FSS-downregulated cell migration (Fig. 6). These results show that either PDGFR-α or β activated by PDGF-CC or DD, increased cell migration. There was no obviously greater effect by PDGFR-α or β. These results show that both PDGFR-α and β play important roles in FSS-depressed migration of PDL cells.

Figure 5.

PDGF-CC rescued FSS-inhibited cell migration. Concentrations of 2.5, 5, or 10 ng/mL PDGF-CC were added to the culture medium in a flow chamber, and PDL cells were loaded with 4 h FSS. Cell migration was rescued compared with 4 h FSS alone. PDGF-CC (10 ng/mL) resulted in better improvement than 2.5 or 5 ng/mL PDGF-CC. The numbers of cells that migrated into the cross areas were analyzed and presented in the panel. Data are mean ± standard deviation of at least three experiments (#p < 0.01).

Figure 6.

PDGF-DD increased FSS-inhibited cell migration. PDGF-DD (2.5, 5, and 10 ng/mL) was added to the culture medium in a flow chamber, and 4 h FSS was loaded on PDL cells. Cell migration increased compared with 4 h FSS alone. PDGF-DD (10 ng/mL) resulted in better improvement than 2.5 and 5 ng/mL PDGF-DD. The numbers of cells that migrated into the cross areas were analyzed and presented in the panel. Data are mean ± standard deviation of at least three experiments (*p < 0.05, #p < 0.01).

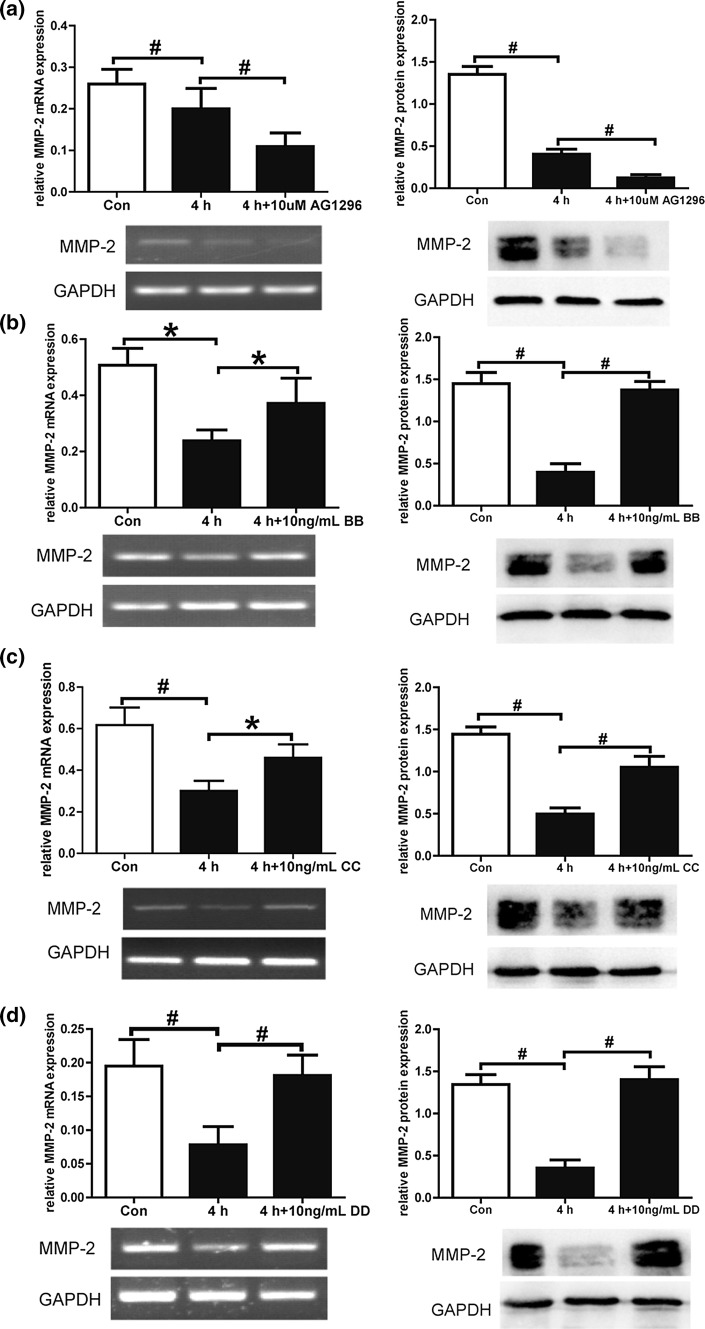

MMP-2 Gene Expression is Regulated by the PDGF Pathway

MMP-2 mainly cleaves gelatin, collagen I, III, IV, elastin, and fibronectin and is an important regulator of cell migration. To investigate the underlying mechanism of FSS-inhibited cell migration, MMP-2 gene expression and the role of PDGFR in the regulation of MMP-2 were studied. A 4 h FSS treatment decreased MMP-2 gene expression, which was in accord with our previous results.26 When the PDGFRs were blocked by AG1296, MMP-2 gene and protein expression in PDL cells both decreased further in response to 4 h of FSS (Fig. 7a). The decrease in MMP-2 gene and protein expression was accelerated when 10 ng/mL PDGF-BB was added to activate PDGFR-α and β (Fig. 7b). MMP-2 gene and protein expression was also upregulated when PDGF-CC (Fig. 7c) or DD (Fig. 7d) was used to activate PDGFR-α or β individually. These results demonstrate that FSS-inhibited cell migration might due to reduced MMP-2 expression. The PDGF pathway plays an important role in FSS-inhibited MMP-2 gene expression. Both PDGFR-α and β are involved in FSS downregulated MMP-2 expression. Activation of PDGFR by PDGF-BB, CC, and DD increased MMP-2 expression and might involve in promoting cell migration.

Figure 7.

MMP-2 expression is regulated by PDGFR. (a) PDL cells were pretreated with or without AG1296 (10 μM) and stimulated by 4 h of FSS. MMP-2 gene and protein expression quantified by RT-PCR decreased in response to 4 h FSS. AG1296 decreased MMP-2 gene (left panel) and protein expression (right panel) compared with 4 h FSS. 10 ng/mL of PDGFR-BB (b), CC (c) and DD (d) increased MMP-2 gene (left panel) and protein expression (right panel) compared with 4 h FSS. Relative mRNA and protein expression was normalized to the expression of GAPDH. Data are mean ± standard deviation of at least three experiments (*p < 0.05, #p < 0.01).

Discussion

PDL is a high turnover tissue, which continually remodels to adapt to physiological functions. Mechanical stress is one of vital factors that initiates tissue remodeling. Shear stress, which is the most common and important type of mechanical stress, regulates cell proliferation, migration, and secretion of growth factors.21,25,26 However, the underlying molecular mechanism has not been revealed. The present study focused on the effects of short duration FSS on proliferation and migration of PDL cells. FSS increased proliferation but inhibited migration of PDL cells. FSS depressed PDGFR-α and β expression. The PDGF pathway was involved in FSS-inhibited cell migration, but may not play a role in FSS-induced cell proliferation.

Mechanical stress regulates cell proliferation depending on the different mechanical types, magnitudes, durations, and different cell types. In our previous study, 12 h of 6 dyn/cm2 FSS inhibited PDL cell proliferation, arresting the cells in the G0/G1 phase25 FSS (3, 6, 9, 12, or 15 dyn/cm2) over a 6-h period significantly increased proliferation of PDL cells.16 A 4–24 h laminar shear stress of 5 or 15 dyn/cm2 induces mesenchymal stem cell (MSC) cycle arrest.8 It has also been reported that 1 h of 20 dyn/cm2 oscillatory shear stress increases MSC proliferation,17 suggesting that short duration FSS benefits proliferation more than long duration FSS. In this study, 4 h of 6 dyn/cm2 FSS significantly increased cell proliferation. Combined with our previous research, these results suggest that short duration FSS, such as 4 or 6 h, promoted cell proliferation and long duration, such as 12 h, inhibited cell growth.

Cell migration is an important process during PDL remodeling. PDL cells migrate to the regenerative or wound healing regions and rebuild new tissues. Mechanical loading produced by mastication, pathological trauma, or iatrogenic tooth movement may regulate PDL cell migration. Our previous study indicated that 12 and 24 h of 6 dyn/cm2 FSS inhibits cell migration.25 A previous study reported that 15 h of 12 dyn/cm2 FSS also inhibits migration of smooth muscle cells (SMCs), but 3 h of the same magnitude of FSS had no effect on migration.16 The migration induced by FSS in SMCs demonstrates the duration-dependent pattern. Our results show that short durations, such as 4 h of FSS, still have an inhibitory effect on PDL cell migration.

PDGFR is a crucial element for various functions, such as wound healing of periodontal tissue.1,14 However, the role of FSS in PDGFRs and how this affects PDL cells is unknown. Whether PDGFRs play a role in FSS-regulated cell behaviors, such as proliferation and migration, remains unknown. In our study, PDGFR-α and β were downregulated by FSS both at the gene and protein levels. It has been reported that PDGFR-β is detectable in normal PDL cells and increases in regenerative tissue. However, in that study, PDGFR-α was not expressed, which might due to individual differences in the studies.18 FSS down-regulates PDGFR-β in SMCs.16 Mechanical stretch increases phosphorylation of PDGFR-α and β in SMC19 and MC3T3 cells.24 Our data indicate that FSS decreased PDGFR-α and β expression in PDL cells, which may have limited activation of the PDGF signaling pathway.

To investigate the role of PDGFR in FSS-regulated PDL cell proliferation, PDGF-BB, which activates both PDGFR-α and β, and AG1296, which is a PDGFR inhibitor, were used. However, activating or inhibiting PDGFR had no effect on PDL cell proliferation, indicating that PDGFRs do not play a role in FSS-regulated proliferation of PDL cells. Oates et al. reported that PDGF stimulates mitogenesis in PDL cells.13 Among the different PDGF isoforms, PDGF-BB displays the maximum mitogenic effect in PDL cells.3 Cyclic stretch increases expression of PDGFR-β, which contributes to proliferation of SMCs.9 In our study, FSS-induced cell proliferation may not have been regulated by the PDGF pathway in PDL cells.

Accumulating studies have demonstrated that PDGFRs are involved in mechanical stress-regulated cell migration,10,15 which led us to investigate the role of PDGFRs in FSS-inhibited migration of PDL cells. We first examined the role of PDGF-BB, which activates both PDGFR-α and β. It has been reported that PDGF-BB has a dose-dependent effect on collagen I synthesis, which is the most important component of the ECM in the PDL. That study showed that among PDL cells treated with 0.1, 1, 3, or 10 ng/mL PDGF-BB, those treated with 1 ng/mL PDGF-BB maximally increased collagen I expression.12 We added 2.5, 5, or 10 ng/mL PDGF-BB to culture medium in a flow chamber, and PDL cells were loaded with FSS. PDGF-BB (2.5 ng/mL) clearly increased cell migration compared with 4 h of FSS, and 10 ng/mL PDGF-BB yielded the maximal effect. This result indicates that PDGF-BB promoted cell migration after exposure to 4 h of FSS. PDGF-BB might bind with PDGFR-α and/or β and activate the downstream signaling pathway to increase cell migration.

PDGFR-α and β play different roles in cell migration due to their different binding affinities to PDGFs. Their responses to mechanical stress also vary. FSS downregulates PDGFR-β expression in SMCs.15 Mechanical stretch increases PDGFR-α activity in osteoblast-like cells.24 To clarify which PDGFR is vital for rescuing FSS-inhibited cell migration, PDGF-CC, which specifically binds with PDGFR-α, and PDGF-DD, which occasionally binds with PDGFR-β, were added to the culture medium. As results, PDGF-CC or DD significantly increased cell migration compared with 4 h of FSS, demonstrating that both PDGFR-α and β play a role rescuing FSS-inhibited cell migration. We did not see any difference between PDGF-CC and DD, suggesting that both PDGFR-α and β might be equally important in FSS-regulated cell migration.

MMPs are important for degradation of the cellular matrix and are vital factors for cell migration. MMPs are widely reported to be regulated by PDGFRs. MMP-9 is regulated by PDGFR in rat brain astrocytes.7 Mechanical stretch activates MMP-13 through PDGFR-α in osteoblast-like cells.24 Our study focused on MMP-2, which is the most important MMP in PDL turnover. MMP-2 expression is regulated by PDGFR-β under FSS in SMCs.15 A 4 h FSS inhibited MMP-2 gene expression, consistent with our previous result.26 Inhibiting PDGFR with AG1296 accelerated the downregulated expression of MMP-2. Activating PDGFR with 10 ng/mL PDGF-BB rescued most of the MMP-2 expression. PDGF-CC and DD yielded the same effect. Our results show that FSS-inhibited PDL cell migration may be due to decreased expression of MMP-2. FSS-induced downregulation of PDGFRs may affect downstream molecules, such as PI3K, Akt, or ERK1/2, to decrease MMP-2 expression.20,24 However, PDGFR-α or β did not have different roles regulating MMP-2.

In conclusion, 4 h of FSS on human PDL cells promoted proliferation but inhibited migration. PDGFR-α and β were both downregulated at the mRNA and protein levels. Activating or inhibiting the PDGFRs had no effect on the FSS-induced increase in proliferation, indicating that PDGFRs do not regulate FSS-induced proliferation of PDL cells. However, activating PDGFR with PDGF-BB, CC, and DD, which individually bind with both PDGFR-α and β, only PDGFR-α or only PDGFR-β, efficiently rescued FSS-inhibited migration. FSS also depressed MMP-2 expression. PDGF-BB, CC, and DD increased MMP-2 expression under FSS indicating the underlying mechanism of FSS-inhibited migration of PDL cells. Our study provides fundamental evidence for clinical tooth movement and regeneration of PDL tissues.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Numbers 11572030), National Key R&D Program of China (2017YFC0108505); National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Numbers 11120101001, 11421202); the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities; the 111 Project (Grant Numbers B13003).

Conflict of interest

All authors including Lisha Zheng, Qiusheng Shi, Jing Na, Nan Liu, Yuwei Guo, Yubo Fan have no conflicts of interest.

Ethical Approval

The authors state that all human subjects research was carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by Beihang University Ethics Committee. This study did not involve any animal research.

Abbreviations

- PDL

Periodontal ligament

- ECM

Extracellular matrix

- PDGF

Platelet-derived growth factors

- FSS

Fluid shear stress

- MAPK

Mitogen-activated protein kinase

- PI3K

Phosphoinositide 3-kinase

- PLC

Phospholipase C

- MMP

Matrix metalloproteinases

- DMEM

Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium

- FBS

Fetal bovine serum

- EdU

5-Ethynyl-2′-deoxyuridine

- PMSF

Phenylmethane sulfonyl fluoride

- SDS-PAGE

Sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis

- PVDF

Polyvinylidene fluoride

- TBS-T

Triethanolamine buffered saline solution

- HRP

Horseradish peroxidase

- ECL

Enhanced chemiluminescent

- MSC

Mesenchymal stem cell

- SMC

Smooth muscle cell

Contributor Information

Lisha Zheng, Phone: +86-10-82314878, Phone: +86-10-82339428, Email: lishazheng@buaa.edu.cn.

Yubo Fan, Phone: +86-10-82314878, Phone: +86-10-82339428, Email: yubofan@buaa.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Andrae J, Gallini R, Betsholtz C. Role of platelet-derived growth factors in physiology and medicine. Genes Dev. 2008;22:1276–1312. doi: 10.1101/gad.1653708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bergsten E, Uutela M, Li X, Pietras K, Ostman A, Heldin CH, Alitalo K, Eriksson U. PDGF-D is a specific, protease-activated ligand for the PDGF beta-receptor. Nat. Cell Biol. 2001;3:512–516. doi: 10.1038/35074588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boyan LA, Bhargava G, Nishimura F, Orman R, Price R, Terranova VP. Mitogenic and chemotactic responses of human periodontal ligament cells to the different isoforms of platelet-derived growth factor. J. Dent. Res. 1994;73:1593–1600. doi: 10.1177/00220345940730100301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Heldin CH, Westermark B. Mechanism of action and in vivo role of platelet-derived growth factor. Physiol. Rev. 1999;79:1283–1316. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1999.79.4.1283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kanzaki H, Chiba M, Shimizu Y, Mitani H. Periodontal ligament cells under mechanical stress induce osteoclastogenesis by receptor activator of nuclear factor kappaB ligand up-regulation via prostaglandin E2 synthesis. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2002;17:210–220. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2002.17.2.210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li X, Ponten A, Aase K, Karlsson L, Abramsson A, Uutela M, Backstrom G, Hellstrom M, Bostrom H, Li H, Soriano P, Betsholtz C, Heldin CH, Alitalo K, Ostman A, Eriksson U. PDGF-C is a new protease-activated ligand for the PDGF alpha-receptor. Nat. Cell Biol. 2000;2:302–309. doi: 10.1038/35010579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lin CC, Lee IT, Chi PL, Hsieh HL, Cheng SE, Hsiao LD, Liu CJ, Yang CM. C-Src/Jak2/PDGFR/PKCdelta-dependent MMP-9 induction is required for thrombin-stimulated rat brain astrocytes migration. Mol. Neurobiol. 2014;49:658–672. doi: 10.1007/s12035-013-8547-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Luo W, Xiong W, Zhou J, Fang Z, Chen W, Fan Y, Li F. Laminar shear stress delivers cell cycle arrest and anti-apoptosis to mesenchymal stem cells. Acta Biochim. Biophys. Sin. (Shanghai) 2011;43:210–216. doi: 10.1093/abbs/gmr004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ma YH, Ling S, Ives HE. Mechanical strain increases PDGF-B and PDGF beta receptor expression in vascular smooth muscle cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1999;265:606–610. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.1718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McGowan SE, McCoy DM. Platelet-derived growth factor receptor-alpha and Ras-related C3 botulinum toxin substrate-1 regulate mechano-responsiveness of lung fibroblasts. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 2017;313:L1174–L1187. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00185.2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Monnouchi S, Maeda H, Fujii S, Tomokiyo A, Kono K, Akamine A. The roles of angiotensin II in stretched periodontal ligament cells. J. Dent. Res. 2011;90:181–185. doi: 10.1177/0022034510382118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ojima Y, Mizuno M, Kuboki Y, Komori T. In vitro effect of platelet-derived growth factor-BB on collagen synthesis and proliferation of human periodontal ligament cells. Oral Dis. 2003;9:144–151. doi: 10.1034/j.1601-0825.2003.02906.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ouyang L, Zhang K, Chen J, Wang J, Huang H. Roles of platelet-derived growth factor in vascular calcification. J. Cell. Physiol. 2018;233:2804–2814. doi: 10.1002/jcp.25985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Page-McCaw A, Ewald AJ, Werb Z. Matrix metalloproteinases and the regulation of tissue remodelling. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2007;8:221–233. doi: 10.1038/nrm2125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Palumbo R, Gaetano C, Melillo G, Toschi E, Remuzzi A, Capogrossi MC. Shear stress downregulation of platelet-derived growth factor receptor-beta and matrix metalloprotease-2 is associated with inhibition of smooth muscle cell invasion and migration. Circulation. 2000;102:225–230. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.102.2.225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Qi L, Zhang Y. The microRNA 132 regulates fluid shear stress-induced differentiation in periodontal ligament cells through mTOR signaling pathway. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 2014;33:433–445. doi: 10.1159/000358624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Riddle RC, Taylor AF, Genetos DC, Donahue HJ. MAP kinase and calcium signaling mediate fluid flow-induced human mesenchymal stem cell proliferation. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2006;290:C776–C784. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00082.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Robbins JR, McGuire PG, Wehrle-Haller B, Rogers SL. Diminished matrix metalloproteinase 2 (MMP-2) in ectomesenchyme-derived tissues of the Patch mutant mouse: regulation of MMP-2 by PDGF and effects on mesenchymal cell migration. Dev. Biol. 1999;212:255–263. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1999.9373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Seo KW, Lee SJ, Kim YH, Bae JU, Park SY, Bae SS, Kim CD. Mechanical stretch increases MMP-2 production in vascular smooth muscle cells via activation of PDGFR-beta/Akt signaling pathway. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e70437. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0070437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Song IS, Jeong YJ, Park JH, Shim S, Jang SW. Chebulinic acid inhibits smooth muscle cell migration by suppressing PDGF-Rbeta phosphorylation and inhibiting matrix metalloproteinase-2 expression. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:11797. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-12221-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.van der Pauw MT, Klein-Nulend J, van den Bos T, Burger EH, Everts V, Beertsen W. Response of periodontal ligament fibroblasts and gingival fibroblasts to pulsating fluid flow: nitric oxide and prostaglandin E2 release and expression of tissue non-specific alkaline phosphatase activity. J. Periodontal Res. 2000;35:335–343. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0765.2000.035006335.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wikesjo UM, Claffey N, Christersson LA, Franzetti LC, Genco RJ, Terranova VP, Egelberg J. Repair of periodontal furcation defects in beagle dogs following reconstructive surgery including root surface demineralization with tetracycline hydrochloride and topical fibronectin application. J. Clin. Periodontol. 1988;15:73–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.1988.tb01558.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wise GE, King GJ. Mechanisms of tooth eruption and orthodontic tooth movement. J. Dent. Res. 2008;87:414–434. doi: 10.1177/154405910808700509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yang CM, Hsieh HL, Yao CC, Hsiao LD, Tseng CP, Wu CB. Protein kinase C-delta transactivates platelet-derived growth factor receptor-alpha in mechanical strain-induced collagenase 3 (matrix metalloproteinase-13) expression by osteoblast-like cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2009;284:26040–26050. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.040154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zheng L, Chen L, Chen Y, Gui J, Li Q, Huang Y, Liu M, Jia X, Song W, Ji J, Gong X, Shi R, Fan Y. The effects of fluid shear stress on proliferation and osteogenesis of human periodontal ligament cells. J. Biomech. 2016;49:572–579. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2016.01.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zheng L, Huang Y, Song W, Gong X, Liu M, Jia X, Zhou G, Chen L, Li A, Fan Y. Fluid shear stress regulates metalloproteinase-1 and 2 in human periodontal ligament cells: involvement of extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) and P38 signaling pathways. J. Biomech. 2012;45:2368–2375. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2012.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]