Abstract

Microtubule not only provides the track for kinesin but also modulates kinesin’s mechanochemical cycle. Microtubule binding greatly increases the rates of two chemical steps occurring inside the nucleotide-binding pocket (NBP) of kinesin, i.e., ATP hydrolysis and ADP release. Kinesin neck linker docking (the key force-generation step) is initiated by the motor head rotation induced by ATP binding which needs an anchor provided by microtubule. These functions of microtubule can only be accomplished through interactions with kinesin. Based on the newly obtained crystal structures of kinesin-microtubule complexes, we investigate the interactions between kinesin’s NBP and microtubule using molecular dynamics simulations. We find that the N-3 motif of NBP has direct interactions with a group of negatively charged residues on α-tubulin through Ser235 and Lys237. These specific long-range interactions induce binding of NBP to microtubule at the right position and assist the formation of the indirect interaction between NBP and microtubule. These interactions between N-3 and microtubule have an important anchor effect for kinesin’s motor domain during its rotation with Ser235 as the rotation center, and also play a crucial role in stabilizing the ATP-hydrolysis environment.

Keywords: Kinesin, Microtubule, Nucleotide-binding pocket, Anchor effect

Introduction

Kinesin-1 (herein referred to as kinesin)23 is the smallest motor protein in life known today. As a nucleotide enzyme, kinesin can convert the energy carried by ATP into directional movement along microtubule and play a crucial role for mitosis and organelle transportation in cells.13,14,48,49 Kinesin is a highly efficient motor with efficiency close to 40% (the work done by kinesin in one step, ~24 kJ/mol, over the energy released by ATP hydrolysis, ~60 kJ/mol).15 The high efficiency is realized by the tight coupling between the chemical steps occurring in kinesin’s NBP and the mechanical steps accomplished by a series of conformational changes of the structural elements.5,12,45,49 In kinesin’s mechanochemical cycling, microtubule plays a crucial role as it is not just kinesin’s moving track but also the activator of its chemical steps. In the absence of microtubule the rate of kinesin’s ATPase is much lower than that in the microtubule-attached state,20,34,44,49 indicating that the NBP of kinesin can sense the existence of the microtubule through an effective communication with microtubule. This communication can only be accomplished through the interactions between NBP and microtubule, which now needs to be addressed clearly.

It is generally accepted that, to achieve kinesin’s processive movement along microtubule, the conformations of kinesin’s mechanical elements, the affinity of kinesin with microtubule and the bound nucleotide are highly coupled with each other.1–3,7 When microtubule is absent or the connection between NBP and microtubule is blocked by mutations.20,34,44,49 the ATPase rate of kinesin drops to a basal level ~1000-fold reduced over the microtubule-attached state.11,38 Further researches showed that microtubule can accelerate nucleotide exchange and hydrolysis by stimulate the ADP release from kinesin.11,31 In kinesin’s mechanochemical cycle, this function of microtubule is considered to “gate” kinesin’s ATPase and, from this point of view, the “ front-head gated mechanism” is proposed.5,32,33,47 It is also shown that the closure of kinesin’s NBP, which is needed for ATP hydrolysis, requires the existence of microtubule.27,28 Until now, the whole walking cycle of kinesin on microtubule cannot be investigated using full atomic molecular dynamics (MD) method. Some researchers use coarse-grained MD simulations to study kinesin’s walking cycle.50,18 However, this method cannot give the key details of interactions between NBP and microtubule at atomic level which is needed for the understanding of how microtubule catalyzes the ATPase of kinesin.

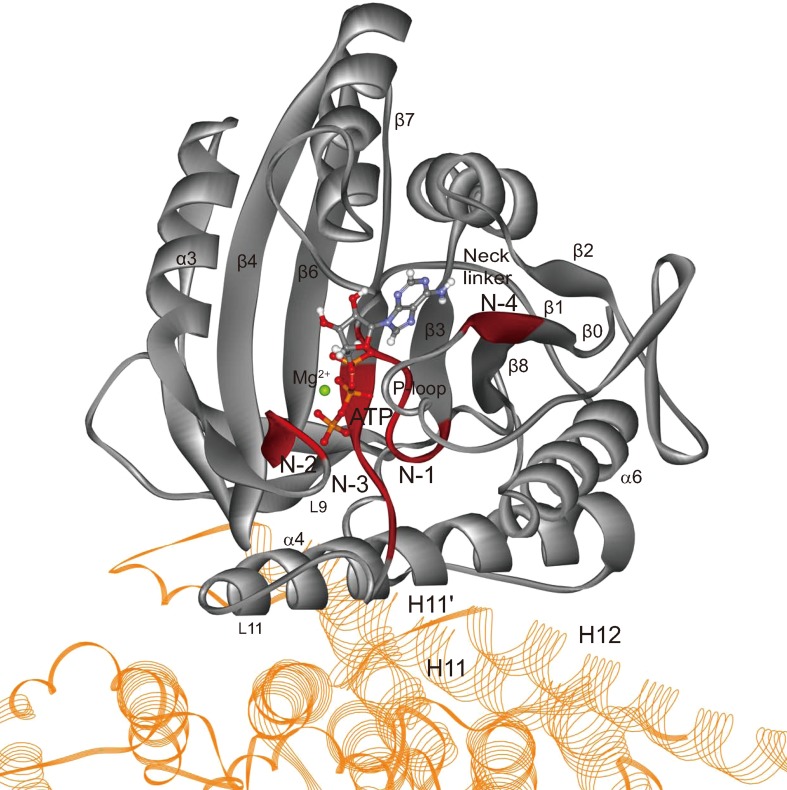

The communication between kinesin’s NBP and microtubule must have a structural basis. The NBPs of members of kinesin superfamily show many similarities with the corresponding region of G proteins, which consist of four motifs, N-1 (P-loop), N-2 (switch-I), N-3 (switch-II) and N-4 (β1) (Fig. 1).35,36,43 These four motifs are highly conservative in the kinesin superfamily35,36 and the entire structure of NBP is a perfect match for ATP molecule in both geometry and interaction (Fig. 1). The functions of NBP is not limited to only binding the nucleotide. A key function of NBP is that it can sense the existence of microtubule and effectively control the mechanochemical transformation process. This control is realized via the interactions between the elements of NBP and microtubule.28 As seen in Fig. 1, most parts of NBP cannot interact directly with microtubule surface. Vale and Milligan49 proposed that the switch-II helix (α4), which is adjacent to N-3 motif, is the key structural element in the communication pathway linking the catalytic site, the polymer binding site, and the mechanical element in kinesin. Kikkawa et al.20 had similar point of view and proposed that the anchoring of the switch-II cluster on the microtubule surface ensure the motor domain rotation in kinesin’s chemical cycle. A systematic mutational analysis of the key residues on microtubule responsible for activation of kinesin’s ATPase by Uchimura et al.46 showed that a cluster of negatively charged residues spanning the helix H11-12 loop and H12 of α-tubulin are critical for kinesin’s motility and ATPase. These residues locate near to the NBP of kinesin motor domain (Fig. 1). Due to lack of the crystal structures of kinesin-microtubule complex, the early investigations cannot give the atomic details of the interactions between NBP and microtubule. Recently, the relationship between kinesin’s motor domain and microtubule was extensively studied using experimental4,6,10,37 and theoretical24,21 methods. The newly obtained crystal structures of kinesin-microtubule complexes by Gigant et al. revealed important details of interactions between motor domain and microtubule in kinesin’s ATP and APO states (PDB ID: 4HNA10 and 4LNU6). By comparing these structures with the structure of ADP-detached state, Gigant et al.10,6 proposed that, along the ATPase cycle, three subdomains have rigid-body movements which distort the nucleotide-binding site and cause ADP release. In this process, the relocation of N-3’s Glu236, which connects L11 loop and interacts with N-2, plays an important role.10 Further, based on the cryo-EM structures of kinesin-microtubule complex with the resolution of 5-6 Å, Shang et al.37 found that Glu236 of N-3 can form hydrogen bond with a conserved residue Asn255 on α4 (the linchpin) that forms a stable interaction between N-3 and α4, and Asn255 can also interact with Met413 of α-tubulin. Since α4 is an important microtubule binding site of kinesin, the linchpin stands for an indirect interaction between NBP and microtubule. Now, there is still a lack of atomic-level analysis of the direct interactions between kinesin’s NBP and microtubule and their functions in kinesin’s mechanochemical cycling.

Figure 1.

Conformation of kinesin’s motor domain (silver) and microtubule (yellow) complex. The nucleotide-binding pocket (N-1, N-2, N-3 and N-4 motifs) of kinesin are highlighted in red color. ATP molecule and Mg2+ are explicitly shown in ball and stick model. H11’ and H12 of α-tubulin are close to NBP’s N-3 motif. Note that the tubulin is shown in part.

The reliable analysis and comparison of the interactions in protein need to be based on the statistics over the microscopic states at physiological temperature, while crystal structures obtained at low temperature only capture one possible conformation of the system. In this work, we set up three MD models of kinesin-microtubule complex, which are surrounded by explicit water molecules at 310 K constant temperature, based on the crystal structures of free motor domain of ADP-state and the kinesin-microtubule complexes in the APO and ATP states. We obtained the stable structures of kinesin-microtubule complexes in different states through MD simulations. We investigate in detail the direct interactions between NBP and microtubule in light of the obtained stable structures and find that kinesin’s NBP can interact with microtubule directly. Ser235 and Lys237 at the C-terminus of NBP’s N-3 motif can form hydrogen bonds and salt bridges with microtubule’s α-tubulin. The hydrogen bonds between Glu236 of N-3 and Asn255 of α4 and that between Asn255 and Gly412 of α-tubulin are indirect interaction between NBP and microtubule. Kinesin’s central β-sheet has a rotation relative to microtubule in the ATP state compared with that in the APO state. The direct and indirect interactions between NBP and microtubule are stable in both APO and ATP states, indicating that N-3 binds tightly to microtubule in the central β-sheet’s rotation process and Ser235 is the rotation center. The interactions between Lys237 and a group of negatively charged residues (Glu414, Glu417 and Glu420) of α-tubulin form the initial contact between NBP and microtubule which assists the formation of the linchpin proposed by Shang et al.37

Methods

The crystal structures we used for modeling are 4HNA,10 4LNU6 and 1BG2.22 4HNA, 4LNU and 1BG2 are all crystal structures of human kinesin. 4HNA is kinesin-microtubule complex which is considered to be in ATP state and 4LNU is that in the APO state. 1BG2 is considered to be in the ADP state with the microtubule is absence. The ADP-ALF of 4HNA was replaced by ATP molecule while the adenosine rings of these two molecules are coincided. The designed ankyrin repeat proteins (DARPin) of 4HNA and 4LNU were deleted in our models. The coordinate water molecules and Mg2+ were maintained. The motor domain of 1BG2 was placed above the tubulin 5 Å. The obtained three kinesin-tubulin complexes were buried in a water sphere (the radius is 70 Å) as the initial conformatrion. TIP3P17 was used to model water molecules. Na+ and Cl− were added to ensure an ionic concentration of 150 mM and zero net charge. The entire model had ~150000 atoms. In our MD simulations, a group of atoms in tubulin (α-carbons of α-tubulin’s Glu168, Leu227, Val353 and α-carbons of β-tubulin’s Thr168, Leu227, Thr353) were fixed to ensure a stable microtubule structure. The software we used for modeling is VMD (version 1.9.2).16 The MD simulations were performed by using NAMD (version 2.9)30 with force field CHARMM25 at constant temperature of 310K. The integration time step is 2 fs. The non-bonded Coulomb and van der Waals interactions were calculated with a cutoff using a switch function starting at a distance of 13 Å and reaching zero at 15 Å. Before the simulation run, the protein-water systems were minimized for 30000 steps. All the three systems were simulated twice with simulations were 40 and 140 ns respectively. The first 5 ns trajectory of each simulation run was eliminated in our analysis. We thus had 130 ns MD trajectory for each system to perform statistical analysis. The criteria of hydrogen bond and salt bridge is as following: the maximum distance between acceptor and hydrogen atoms of a hydrogen bond is 3 Å; the maximum distance of two charged groups (the central carbon atoms which connect to the charged atoms) is 8 Å. The criteria of hydrogen bond between Ser235 of kinesin and Glu414 of α-tubulin is larger (the distance between hydrogen atom of Ser235 and carbon atom of Glu414 which connect to the charged atoms is shorter than 5.5 Å) because Glu414 is a charged residue and its hydrogen-bonding interaction with other residues is stronger than normal hydrogen bond. Molecular drawings in this paper were produced using Discovery studio 3.5 visualizer.

Results and Discussion

Direct Interactions Between Kinesin’s NBP and Microtubule

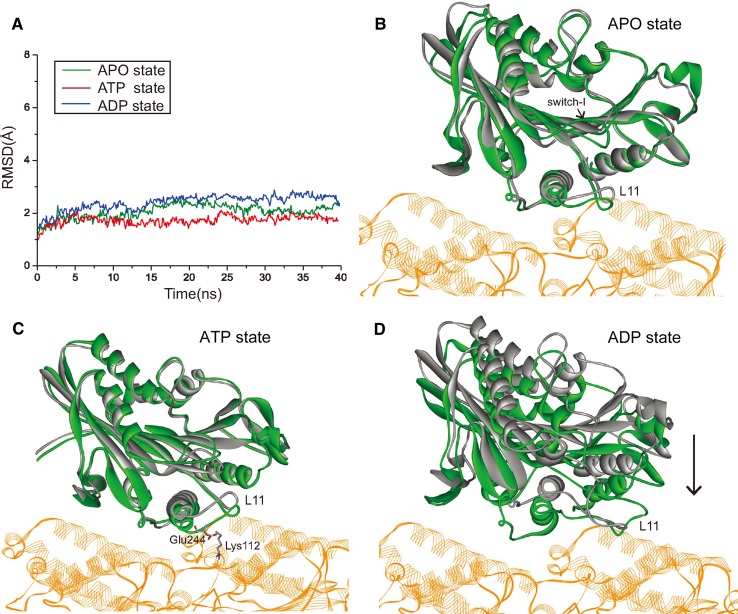

The newly obtained crystal structures of kinesin-microtubule complexes in the APO and ATP states provide us the proper initial structures to perform MD simulations. By burying these two crystal structures in water spheres respectively, we perform 140 ns MD simulations for each model (see Methods). Because there is still no crystal structure of kinesin-microtubule complex with kinesin in ADP state, we dock the ADP-state kinesin’s motor domain to microtubule through MD simulations (see Methods). In the MD simulations, all the three kinesin-microtubule complexes are sufficiently equilibrated and reach stable states (Fig. 2a). The conformational differences between the crystal structures and the stable simulation structures are small and the significant differences mainly occur at the loop regions, which is consistent with the feature of protein’s loop structure in water and thermal environment. Because part of the switch-I (N-2 motif) region of NBP is missed in the crystal structure of kinesin-tubulin complex in APO state, we added the missed residues of switch-I in our MD simulation. In the MD simulations for the APO state complex, the switch-I is flexible due to lack of nucleotide (Fig. 2b). For the ATP-state complexes, the major conformational difference occurs at the N-terminal part of α4 and loop L11 which show large displacement toward α-tubulin (Fig. 2c). A salt bridge formed between Glu244 of kinesin’s L11 loop and Lys112 of α-tubulin can be identified in the simulation structure and this salt bridge is absent in the ATP-state crystal structure. This salt bridge might be responsible for the large displacement of α4 and L11. Since no crystal structure for the ADP-state kinesin-microtubule complex is available, we place the ADP-state structure of kinesin’s motor domain above tubulin (5 Å) and simulate its binding process. The motor domain docks quickly to tubulin and reaches a stable binding state on tubulin. We call this stable structure the first contact complex of ADP-state kinesin and microtubule because kinesin always docks to microtubule in ADP state. The most important conformational difference occurs again at the N-terminal part of α4 and loop L11 (Fig. 2d).

Figure 2.

MD simulation results of kinesin-microtubule complexes with kinesin in APO, ATP and ADP states respectively. a The RMSD values of three models. The fluctuations of the three RMSD values after 5 ns are all within 0.5 Å which indicate that the complexes are sufficiently equilibrated and reach stable states. This figure is prepared by using Origin 8.5. b and c Superpossed structures of crystal structure (silver) and the stable structure (green) after MD simulations in the b APO state and in the c ATP state. α- and β-tubulin are shown in brown color. The added switch-I in APO state of the simulated stable structure is flexible due to lack of nucleotide. The obtained stable structure in ATP state shows large displacement of L11 loop toward tubulin relative to the crystal structure due to a salt bridge formed between Glu244 of L11 and Lys112 of α-tubulin. d Superposition of the ADP-state initial crystal structure (silver) and stable simulation structure (green) binding to tubulin. The black arrow shows the displacement of kinesin’s motor domain in the simulation. Note that the tubulin is shown in part.

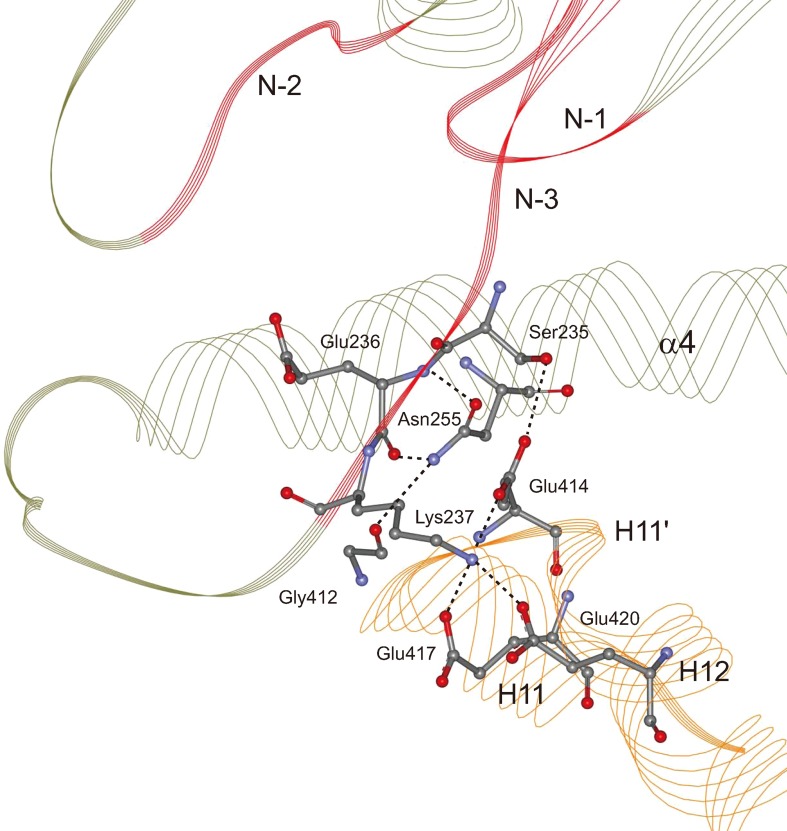

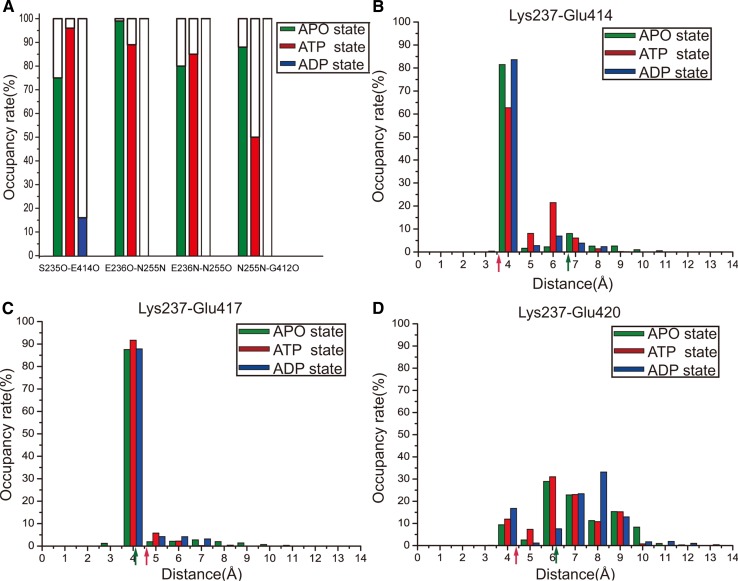

Direct interactions between NBP and microtubule. Careful inspection of the NBP residues of our newly obtained stable structures shows that NBP’s N-1, N-2 and N-4 motifs cannot interact with microtubule directly. The N-3 motif, which locates at the N-terminus of L11 loop, can form direct interaction with microtubule in all the three kinesin-tubulin complexes (Fig. 3). Ser235 of the N-3 motif forms a hydrogen bond with Glu414 of α-tubulin. However, the stability of this hydrogen bond is different in different nucleotide state (see Fig. 4a). In the ATP state, it is very stable. The formation time of this hydrogen bond in the ATP state occupies ~100% of the simulation time, which defines the occupancy rate. This data drops to 70%-80% in the APO state and, in the ADP state, it only forms occasionally (occupancy rate 10%-20%). There is another direct interacting site between NBP and microtubule. The positively charged side chain of Lys237 at the C-terminus of N-3 is buried in a pocket formed by three negatively charged residues (Glu414, Glu417 and Glu420) of α-tubulin (Fig. 3). The salt bond interaction between Lys237 and the pocket is very strong and highly stable in the three nucleotide states (Fig. 4b–4d). The strength and stability of the salt bonds are directly described by the bond length distribution. As seen in Fig. 4b and 4c, the bond lengths for the salt bonds Lys237-Glu414 and Lys237-Glu417 are almost concentrated at 4 nm in the three nucleotide states, meaning that they are very strong. The salt bond between Lys237 and Glu420 is relatively weaker as shown in Fig. 4d. In Fig. 4b–4d, we also show the bond lengths of the three salt bonds in the APO and ATP state crystal structures (indicated by the solid arrow heads). It is apparently seen that there is a significant discrepancy between the results from our statistical data obtained under ambient condition and that from crystal structures obtained at low temperature. Take the salt bond Lys237-Glu414 for example. As seen in Fig. 4b, from the crystal structures, the bond in the ATP state (bond length 3.65 Å) is much stronger than that in the APO state (bond length 6.7 Å). However, the statistical distribution for the bond length from our simulation shows an opposite situation, i.e., the bond in the APO state is stronger than that in the ATP state, indicating that care must be taken when applying structural data obtained at low temperature.

Figure 3.

Direct and indirect interactions between kinesin’s nucleotide-binding pocket and microtubule. Elements of kinesin’s motor domain are shown in green and that of tubulin are shown in yellow. Motifs of NBP are shown in red. The atoms of related residues are explicitly shown with hydrogen atoms omitted. The hydrogen bonds and salt bridges are shown with dotted lines.

Figure 4.

Statistical data of direct and indirect interactions between NBP and microtubule in three nucleotide states. a Occupancy rates of hydrogen bonds between NBP and microtubule in APO (green), ATP (red) and ADP (blue) state respectively. b–d Occupancy rates of salt bonds between Lys237 and the negatively-charged pocket (Glu414, Glu417 and Glu420) of α-tubulin with respect to bond length. The solid arrow heads indicate the bond lengths in crystal structures. This figure is drawn by using Origin 8.5.

The conservation analysis shows that the direct interacting site via Ser235 and Lys237 is conservative in kinesin-1 subfamily. Uchimura et al.46 performed a mutational investigation on “ key residues on microtubule responsible for activation of kinesin ATPase”. They found that a cluster of negatively charged residues of α-tubulin (Glu414, Glu417 and Glu420) are critical for kinesin motility. This result directly supports our finding here. Because Lys237 is buried in this cluster in all the three nucleotide states, these negatively charged residues are the anchoring site of kinesin’s NBP to microtubule. Among these negatively charged residues, Glu414 is special in that it is important for coupling microtubule binding and ATPase activation.46 In our simulation work, the specialness of Glu414 is that it interacts with both Ser235 and Lys237 stably in the APO and ATP states, based on which an explanation of the special role of Glu414 will be given later.

Indirect interactions between NBP and microtubule. In both APO and ATP state, the backbone of Glu236 at the C-terminus of N-3 forms two standard hydrogen bonds with Asn255 of α4. In the meantime, Asn255 also forms a hydrogen bond with Gly412 of α-tubulin (Fig. 3). Because the binding between kinesin’s α4 and microtubule is stable, the hydrogen bonds between Glu236 and Asn255 are indirect interactions between NBP and microtubule. Sindelar et al.38,37, 41 first recognized this important interaction and called Asn255 as “ linchpin residue”. The linchpin hydrogen bonds are more stable in the APO state than that in the ATP state (~90% in APO state vs ~50% in ATP state) (Fig. 4a). In the first-contact ADP state, these hydrogen bonds do not exist. In the microtubule-free ADP state and our stable first-contact ADP state, the N-terminus of α4 uncoils just from the position of Asn255, indicating that linchpin formation and α4 extension are closely linked with each other.

Anchor Effect of Interactions Between NBP and Microtubule

It is believed that ATP binding to the NBP can induce a rotation of kinesin’s motor domain.19,38–42 We superimpose the obtained stable structures in the APO and ATP state in Fig. 5. As seen, the main conformational change in the ATP binding process is an anticlockwise rotation of the motor domain except α4, which is nearly fixed in the two states. The motor domain rotation has two important functions: first, it transforms the conformation of NBP from APO state, which is suitable for ATP binding, to ATP state which is needed for ATP hydrolysis; second, it initiates the neck linker docking process and forms the mechanical pathway from ATP binding to neck linker docking. The interactions between NBP and microtubule play crucial roles in these two aspects.

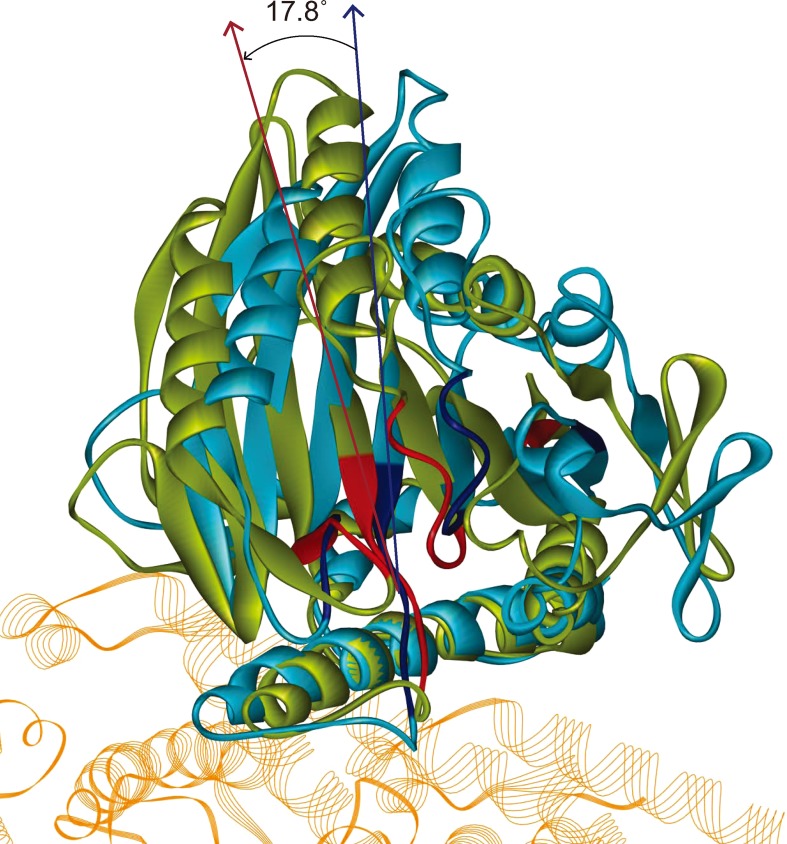

Figure 5.

Superposition of the obtained stable complex structures in APO (blue) and ATP (green) state. The NBPs of the corresponding structures are highlighted. The main conformational change caused by ATP binding is an anticlockwise rotation (~17.8°) of the motor domain with Ser235 as the rotation center.

Stabilizing the environment for ATP hydrolysis. The ATP-binding induced rotation switch the motor domain from the APO state conformation to the ATP bound state one, in which the ATP hydrolysis will take place. However, to achieve a successful hydrolysis reaction, the participant components must be kept sufficiently stable with the distance fluctuation of those key atoms within ~0.5 Å. The microtubule provides a firm basis for the ATP hydrolysis related components through the interactions between NBP and microtubule.

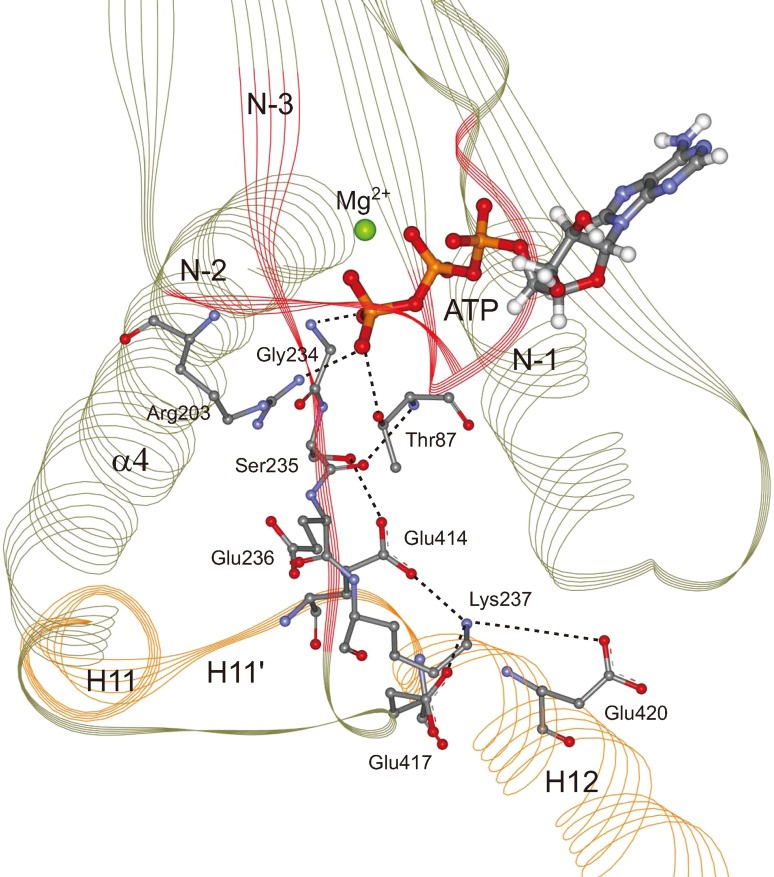

In Fig. 6, we depict explicitly the ATP molecule and the key residues for ATP hydrolysis in the ATP-bound state. As seen, the γ-phosphate of ATP forms a strong hydrogen bond with Gly234 of N-3. The formation of this hydrogen bond is the signature of the complete binding of ATP in the NBP. Because the anchor residues Ser235, Glu236 and Lys237 bind tightly to microtubule and α4 in both state and ATP state, Gly234 adjacent to Ser235 is fixed firmly and thus the ATP molecule obtains a stable binding site.

Figure 6.

The environment for ATP hydrolysis. ATP molecule, the key residues for ATP hydrolysis and their interactions with each other are explicitly shown. The signature of the complete binding of ATP into the NBP is the hydrogen bond formed between Gly234 and γ-phosphate of ATP molecule. Thr87 can interact with the anchor residue, Ser235, by forming a hydrogen bond. The positional relationship among ATP, Thr87, Glu236 and Arg203 are different from that for Eg5, i.e., the ATP hydrolysis environment for kinesin-1 is different from that for Eg5, that indicates a different mechanism of ATP hydrolysis for kinesin-1.

Thr87 of N-1, Glu236 of N-3 and Arg203 of N-2 are believed to be the key residues for ATP hydrolysis. The works on the ATP hydrolysis in Eg5 kinesin (a member of kinesin-5) suggested that the proton transfer pathway in ATP hydrolysis is accomplished by two water molecules with assistance of the three residues.29,26 In the ATP-state kinesin-microtubule complex, we find that Thr87 directly interacts with the anchor residue Ser235 by forming a standard backbone hydrogen bond (Fig. 6), which contributes significantly to the positing and stabilizing of Thr87. Glu236 has a stable position since it is anchored to Asn255 of α4. The hydrogen bonds between Glu236 and Asn255 are highly stable (Fig. 4a) which ensure the stabilization of Glu236. However, it should be pointed out that the high stability of these hydrogen bonds is closely related to the direct interactions of the other two anchor residues (Ser235 and Lys237) with microtubule, which protect the hydrogen-bonding atoms from water attack. In the absence of microtubule, these hydrogen bonds could not even exist.

It is noteworthy that in the stable simulation conformation of the ATP-state kinesin-microtubule complex, the positional relationship among ATP, Thr87, Glu236 and Arg203 is different from that for Eg5. As seen from Fig. 6, Thr87 and Arg203 have direct interactions with the γ-phosphate of ATP without water molecules in between, that is different with the case of Eg5.29,26 In addition, the salt bridge between Glu236 and Arg203 seems not quite strong in our simulations. Even though the structures of N-2 and N-3 motifs of Eg5 and kinesin-1 are quite similar, a difference for the anchor residues might be important: at the position of Lys237 in kinesin-1, the corresponding residue in Eg5 is an asparagine (Asn271 in Eg5, pdb ID: 3HQD29). The strong interactions between Lys237 of kinesin-1 and the negatively charged pocket of microtubule limit its neighboring residue, Glu236, in a position different from that of the corresponding residue, Glu270, in Eg5. This might explain why the Glu236-Arg203 salt bridge in kinesin-1 is weak. These facts together indicate that the ATP hydrolysis mechanism for kinesin-1 might be different from that for Eg5.

Rotation center of the motor domain. ATP-binding induced motor domain rotation is the key step for kinesin’s force generation process, which drives the neck linker docking to the motor domain.9,8 The rotation takes place from the APO-state conformation to the ATP-state conformation, while in both conformations the three anchor residues bind tightly to the microtubule. Therefore, the anchor of N-3 motif’s C-terminus to microtubule provides an axis for motor domain rotation with Ser235 as the rotation center. As seen in Fig. 5, the ATP-state conformation has anticlockwise rotation (~17.8°) relative to that of the APO state while the C-termini of the two N-3 motifs keep coincided.

Neck linker docking process is initiated by the forward movement of the first three residues of neck linker upon the motor domain rotation. The β-domain formed by β1a, β1b and β1c functions as a crucial mechanical amplifier in forming the mechanical pathway from the motor domain rotation to neck linker docking. As shown in our previous work,9,8 the β-domain effectively enlarges the distance between the rotation center and the initial part of the neck linker so that the first three residues and the entire neck linker can get a large enough forward displacement during the rotation of the motor domain. To ensure this amplification function of β-domain accomplish effectively, the rotation center of the motor domain (Ser235) must be fixed firmly. The tight binding of the three anchor residues to the microtubule provides the needed stable mechanical support.

First Contact site Between NBP and Microtubule

Before contact with microtubule, kinesin’s motor domain is in the ADP state with a short α4 and a long extended L11 (e.g., the crystal structure 1BG222). However, the cryo-EM experiments showed that the microtubule-bound ADP-state motor domain exhibited a long α4 with the N-terminus of it extended by several turns.41,19 The extension of α4 is an important effect of microtubule binding, then the microtubule will catalyze ADP release from the NBP and those following chemical steps. To study how the microtubule binding start, we place the crystal structure of motor domain in the ADP state 5 Å above the tubulin in our MD simulations and observe the interactions between microtubule and kinesin in the motor domain docking process (Fig. 2d). Inspection of the docking trajectory shows that the salt bridge between Lys237 and the negatively charged group of α-tubulin is one of the firstly formed direct interactions between ADP-state motor domain and microtubule, the other one is the salt bridge between Arg278 and a negatively charged group of β-tubulin (Glu196, Glu420 and Asp427 of β-tubulin).

In the MD simulations, the docking of the ADP-state motor domain to the microtubule takes ~5 ns, and then a stable conformation of the kinesin-microtubule complex is formed in the rest of the trajectory. In this stable conformation, Lys237 keeps tight binding to the α-tubulin but α4 has no extension, indicating that this stable conformation is just the first contact conformation of ADP-state kinesin and the fully extension of α4 might need a much longer time. In this first contact conformation, the anchor effect of Ser235 is rather weak and the indirect interaction between Glu236 and microtubule through Asn255 (the linchpin) is totally lost (Fig. 4a). Formation of this indirect interaction needs the elongation of α4’s N-terminus that places Asn255 in the stable position to interact with Glu236 of N-3 motif and Gly412 of α-tubulin. Asn255 just locates at the site where α4 starts uncoiling in the ADP state, therefore the short-range hydrogen bond of the linchpin cannot be formed even though the anchor effects of Lys237 and Ser235 put Glu236 close to the right position. This indicates that the anchor effects of Lys237 and Ser235 are necessary for the formation of the linchpin but not sufficient. The extension of α4 needs cooperation of the other residues on L11 loop, of which, we believe, Lys252 should be a crucial one as, in the extended conformation of α4, this residue has a stable interaction with two negatively charged residues on tubulin (Asp163 of β-tubulin and Glu411 of α-tubulin).

Special role of Glu414 of α -tubulin. As shown in the above results and analysis, the interactions between the three anchor residues, Ser235, Glu236 and Lys237, and microtubule play important roles in both chemical and mechanical steps of kinesin. Glu414, Glu417 and Glu420 of α-tubulin form the interaction sites for the direct interactions between Ser235/Lys237 and microtubule. Glu414 is special among the three residues as it forms the specific binding site for Lys237 together with the other two residues and, at the same time, it is the single binding site of Ser235. Through the strong interaction with both Ser235 and Lys237, Glu414 provides a natural coupling between the chemical step and mechanical step for kinesin. Chemically, Ser235 plays a crucial role for stabilizing the ATP hydrolysis environment. Mechanically, Ser235 forms the rotation center for kinesin’s motor domain and Lys237 is a key microtubule-binding site of kinesin. Both chemical and mechanical steps need the fixation support of Glu414. This function of Glu414 provides an explanation (at least in part) for the experimental fact of the special role of Glu414 found by Uchimura et al.46

Conclusions

The accomplishment of the mechanochemical cycling of kinesin needs the assistance of microtubule via the interactions between kinesin and microtubule. The interactions between NBP and microtubule are of special importance since it affects both the chemical steps inside NBP and the mechanical steps of the motor domain. Three anchor residues, Ser235, Glu236 and Lys237, at the C-terminus of the N-3 motif of NBP are responsible for producing the interactions between NBP and microtubule. In addition to the early found indirect interaction between Glu236 and microtubule via Asn255 on α4 (the linchpin), we find that Ser235 and Lys237 interact directly and specifically with a group of negatively charged residues on α-tubulin (Glu414, Glu417, Glu420) which form a binding pocket for Lys237. The interaction between Lys237 and the binding pocket is highly stable in all the three nucleotide states. In the ADP state, Lys237 is the first microtubule contact site of NBP and the entire motor domain. The tight binding of Lys237 to microtubule provides a necessary condition for the formation of the linchpin and the extension of α4. The stable interactions of the three anchor residues with the microtubule in APO and ATP states form a firm mechanical support for the ATP-binding induced motor domain rotation with Ser235 as the rotation center, ensuring the amplification function of the β-domain in initiating the neck linker docking. In the ATP state, the three anchor residues provide a firm basis for the formation of a stable environment needed for ATP hydrolysis. Since kinesin-1 has an important structural difference from a member of kinesin-5, Eg5, at the position of Lys237, the positional relationship among ATP and those ATP-hydrolysis related residues for kinesin-1 is different from that for Eg5. We thus propose that the ATP hydrolysis mechanism of kinesin-1 might be different from that of Eg5 and the future investigation on kinesin-1’s ATP hydrolysis mechanism must consider the influence of microtubule.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China under Grant Nos. 11545014, 11605038 and the Open Project Program of State Key Laboratory of Theoretical Physics, Institute of Theoretical Physics, Chinese Academy of Science, China (Grant No. Y5KF211CJ1).

Conflict of Interest

Yumei Jin, Yizhao Geng, Lina Lü, Yilong Ma, Gang Lü, Hui Zhang, and Qing Ji declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Ethical Standards

No human studies were carried out by the authors for this article. No animal studies were carried out by the authors for this article.

Contributor Information

Yizhao Geng, Phone: +86-22-60435643, Email: gengyz@hebut.edu.cn.

Qing Ji, Email: jiqingch@hebut.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Asenjo AB, Krohn N, Sosa H. Configuration of the two kinesin motor domains during ATP hydrolysis. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2003;10:836–842. doi: 10.1038/nsb984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Asenjo AB, Sosa H. A mobile kinesin-head intermediate during the ATP-waiting state. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:5657–5662. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0808355106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Asenjo AB, Weinberg Y, Sosa H. Nucleotide binding and hydrolysis induces a disorder-order transition in the kinesin neck-linker region. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2006;13:648–654. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Atherton, J., I. Farabella, I.-M. Yu, S. S. Rosenfeld, A. Houdusse, et al.. Conserved mechanisms of microtubule-stimulated ADP release, ATP binding, and force generation in transport kinesins. eLife 3:e03680, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Block SM. Kinesin motor mechanics: Binding, stepping, tracking, gating, and limping. Biophys J. 2007;92:2986–2995. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.100677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cao L, Wang W, Jiang Q, Wang C, Knossow M, et al. The structure of apo-kinesin bound to tubulin links the nucleotide cycle to movement. Nat Commun. 2014;5:5364. doi: 10.1038/ncomms6364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Crevel I, Lockhart A, Cross RA. Weak and strong states of kinesin and ncd. J Mol Biol. 1996;257:66–76. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Geng Y, Ji Q, Liu S, Yan S. Initial conformation of kinesin’s neck linker. Chin Phys B. 2014;23:108701. doi: 10.1088/1674-1056/23/10/108701. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Geng Y, Liu S, Ji Q, Yan S. Mechanical amplification mechanism of kinesin’s β-domain. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2014;543:10–14. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2013.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gigant B, Wang W, Dreier B, Jiang Q, Pecqueur L, et al. Structure of a kinesin-tubulin complex and implications for kinesin motility. Nat Struct Mol Bio. 2013;20:1001–1007. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hackney DD. Kinesin atpase: rate-limiting ADP release. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1988;85:6314–6318. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.17.6314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hancock WO, Howard J. Processivity of the motor protein kinesin requires two heads. J Cell Biol. 1998;140:1395–1405. doi: 10.1083/jcb.140.6.1395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hirokawa N, Niwa S, Tanaka Y. Molecular motors in neurons: Transport mechanisms and roles in brain function, development, and disease. Neuron. 2010;68:610–638. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.09.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hirokawa N, Noda Y. Intracellular transport and kinesin superfamily proteins, kifs: Structure, function, and dynamics. Physiol Rev. 2008;88:1089–1118. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00023.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Howard J. Mechanics of motor proteins and the cytoskeleton. Sunderland: Sinauer Associates Inc; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Humphrey W, Dalke A, Schulten K. Vmd: Visual molecular dynamics. J Mol Graphics. 1996;14:33–38. doi: 10.1016/0263-7855(96)00018-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jorgensen WL, Chandrasekhar J, Madura JD, Impey RW, Klein ML. Comparison of simple potential functions for simulating liquid water. J Chem Phys. 1983;79:926–935. doi: 10.1063/1.445869. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kanada R, Kuwata T, Kenzaki H, Takada S. Structure-based molecular simulations reveal the enhancement of biased brownian motions in single-headed kinesin. PLoS Comput Biol. 2013;9:e10022907. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1002907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kikkawa M, Hirokawa N. High-resolution cryo-EM maps show the nucleotide binding pocket of KIF1A in open and closed conformations. EMBO J. 2006;25:4187–4194. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kikkawa M, Sablin EP, Okada Y, Yajima H, Fletterick RJ, et al. Switch-based mechanism of kinesin motors. Nature. 2001;411:439–445. doi: 10.1038/35078000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Krukau A, Knecht V, Lipowsky R. Allosteric control of kinesin’s motor domain by tubulin: a molecular dynamics study. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 2014;16:6189–6198. doi: 10.1039/c3cp53367k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kull FJ, Sablin EP, Lau R, Fletterick RJ, Vale RD. Crystal structure of the kinesin motor domain reveals a structural similarity to myosin. Nature. 1996;380:550–555. doi: 10.1038/380550a0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lawrence CJ, Dawe RK, Christie KR, Cleveland DW, Dawson SC, et al. A standardized kinesin nomenclature. J Cell Biol. 2004;167:19–22. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200408113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li M, Zheng W. All-atom structural investigation of kinesin-microtubule complex constrained by high-quality cryo-electron-microscopy maps. Biochemistry. 2012;51:5022–5032. doi: 10.1021/bi300362a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.MacKerell AD, Bashford D, Bellott RL, Dunbrack J.D. Evanseck, et al. All-atom empirical potential for molecular modeling and dynamics studies of proteins. J Phys Chem B. 1998;102:3586–3616. doi: 10.1021/jp973084f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McGrath MJ, Kuo I-FW, Hayashi S, Takada S. Adenosine triphosphate hydrolysis mechanism in kinesin studied by combined quantum-mechanical/molecular-mechanical metadynamics simulations. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135:8908–8919. doi: 10.1021/ja401540g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Naber N, Minehardt TJ, Rice S, Chen X, Grammer J, et al. Closing of the nucleotide pocket of kinesin-family motors upon binding to microtubules. Science. 2003;300:798–801. doi: 10.1126/science.1082374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Naber N, Rice S, Matuska M, Vale RD, Cooke R, et al. EPR spectroscopy shows a microtubule-dependent conformational change in the kinesin switch 1 domain. Biophys J. 2003;84:3190–3196. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(03)70043-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Parke CL, Wojcik EJ, Kim S, Worthylake DK. ATP hydrolysis in eg5 kinesin involves a catalytic two-water mechanism. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:5859–5867. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.071233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Phillips JC, Braun R, Wang W, Gumbart J, Tajkhorshid E, et al. Scalable molecular dynamics with namd. J Comput Chem. 2005;26:1781–1802. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Reubold TF, Eschenburg S, Becker A, Kull FJ, Manstein DJ. A structural model for actin-induced nucleotide release in myosin. Nat. Struct. Biol. 2003;10:826–830. doi: 10.1038/nsb987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rosenfeld SS, Fordyce PM, Jefferson GM, King PH, Block SM. Stepping and stretching: How kinesin uses internal strain to walk processively. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:18550–18556. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M300849200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rosenfeld SS, Xing J, Jefferson GM, Cheung HC, King PH. Measuring kinesin’s first step. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:36731–36739. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M205261200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sablin EP, Fletterick RJ. Nucleotide switches in molecular motors: Structural analysis of kinesins and myosins. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2001;11:716–724. doi: 10.1016/S0959-440X(01)00265-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sablin EP, Kull FJ, Cooke R, Vale RD, Fletterick RJ. Crystal structure of the motor domain of the kinesin-related motor ncd. Nature. 1996;380:555–559. doi: 10.1038/380555a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sack S, Kull FJ, Mandelkow E. Motor proteins of the kinesin family structures, variations, and nucleotide binding sites. Eur J Biochem. 1999;262:1–11. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.1999.00341.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shang, Z., K. Zhou, C. Xu, R. Csencsits, J. C. Cochran, et al.. High-resolution structures of kinesin on microtubules provide a basis for nucleotide-gated force-generation. eLife 3:e04686, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 38.Sindelar C. A seesaw model for intermolecular gating in the kinesin motor protein. Biophys. Rev. 2011;3:85–100. doi: 10.1007/s12551-011-0049-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sindelar CV, Budny MJ, Rice S, Naber N, Fletterick R, et al. Two conformations in the human kinesin power stroke defined by x-ray crystallography and epr spectroscopy. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2002;9:844–848. doi: 10.1038/nsb852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sindelar CV, Downing KH. The beginning of kinesin’s force-generating cycle visualized at 9-Å resolution. J Cell Biol. 2007;177:377–385. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200612090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sindelar CV, Downing KH. An atomic-level mechanism for activation of the kinesin molecular motors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:4111–4116. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0911208107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Skiniotis G, Cochran JC, Müller J, Mandelkow E, Gilbert SP, et al. Modulation of kinesin binding by the C-termini of tubulin. EMBO J. 2004;23:989–999. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Smith C, Rayment I. Active site comparisons highlight structural similarities between myosin and other p-loop proteins. Biophys J. 1996;70:1590–1602. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(96)79745-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Song H, Endow SA. Decoupling of nucleotide- and microtubule-binding sites in a kinesin mutant. Nature. 1998;396:587–590. doi: 10.1038/25153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Toprak, E., A. Yildiz, M. T. Hoffman, S. S. Rosenfeld and P. R. Selvin. Why kinesin is so processive. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 106:12717–12722, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 46.Uchimura S, Oguchi Y, Hachikubo Y, Ishiwata S, Muto E. Key residues on microtubule responsible for activation of kinesin ATPase. EMBO J. 2010;29:1167–1175. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2010.25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Uemura S, Ishiwata S. Loading direction regulates the affinity of ADP for kinesin. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2003;10:308–311. doi: 10.1038/nsb911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Vale RD. The molecular motor toolbox for intracellular transport. Cell. 2003;112:467–480. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(03)00111-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Vale RD, Milligan RA. The way things move: Looking under the hood of molecular motor proteins. Science. 2000;288:88–95. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5463.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhang Z, Thirumalai D. Dissecting the kinematics of the kinesin step. Structure. 2012;20:628–640. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2012.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]