Abstract

Renal replacement therapy is guaranteed for all US citizens with end-stage renal disease (ESRD). Undocumented immigrants with ESRD are a particularly vulnerable subset of renal failure patients. There is no federal legislation for these patients except for the requirement to treat them during “emergency medical conditions” and federal legislation excluding them from the guarantee of renal replacement therapy described above. Different states have developed different methods for dealing with this problem, with variation in management even addressed on a center by center basis. This review of the original studies published in the literature reveals the medical, ethical, and financial problems with this situation. These patients frequently have delayed presentation to care, poor access to routine care, increased complications, increased utilization of services, and increased morbidity and mortality in an emergent dialysis model compared to chronic outpatient care. They present an ethical dilemma for practitioners who know they are providing substandard care and occasionally making decisions on how to allocate resources. Emergent dialysis is associated with inadequate reimbursement, increased threat to sustained unemployment, and an overburdening of our healthcare infrastructure. This practice puts patients at risk, places an unfair ethical burden on providers and is financially unsustainable. Special considerations described for kidney transplant and peritoneal dialysis are considered and considerations for a new model are reviewed in the paper. Ultimately accommodations must be made with the input of government, healthcare practitioners, and facilities needs to be reached to protect these vulnerable patients.

KEY WORDS: health policy, immigrants, underserved populations, renal disease, disparities

CLINICAL VIGNETTE

G.V. is a 41-year-old Hispanic female with stage V chronic kidney disease secondary to IgA nephropathy. This was originally diagnosed 4 years ago and has progressively worsened. Her current glomerular filtration rate is 7 mL/min. Dialysis is imminent. On her most recent hospitalization for fluid overload and hyperglycemia, this was discussed at length with her primary team and the nephrology service. She is an undocumented immigrant, uninsured, and married with three children with no financial means to pay for medical care. There is no means for an uninsured, undocumented immigrant to receive dialysis in her county. Despite her impending need for renal replacement therapy (RRT), no vascular surgeon will agree to place an arteriovenous graft or fistula. The patient currently has no means to pay for dialysis access or renal replacement therapy. Frequent ER visits with temporary access will be her only option.

BACKGROUND

In the early days of renal replacement in the USA, the Admissions and Policies Committee of the Seattle Artificial Kidney Center at Swedish Hospital set a precedent by deciding how to ration this incredible new resource among their population of patients with end-stage renal disease (ESRD).1 After an article was published in Life regarding this committee of lay people—known colloquially as “The God Committee”—there was the beginning of a public outcry. Local and national advocacy contributed to the decision to add a Medicare entitlement to all patients with ESRD in 1972, guaranteeing financial coverage for this vulnerable population, which now includes over 650,000 American citizens.2–4

Undocumented immigrants requiring RRT are a uniquely vulnerable population without access to this Medicare entitlement. As foreign born individuals without appropriate documentation (e.g., visas, green cards, or citizenship), these patients are typically low-income and uninsured, and two-thirds live in California, Texas, Florida, New York, Arizona, Illinois, New Jersey, and North Carolina.5,6 Most of these immigrants are from Mexico, followed by other Central and South American nations.7 It is estimated that 5000 to 7000 of the 10 to 12 million undocumented immigrants in the USA have ESRD.8–10

Undocumented immigrants may have originally been able to take advantage of the Medicare entitlement; however, in 1986, the Consolidated Omnibus Reconciliation Act prohibited immigrants “not lawfully admitted” from public benefits.8 Acute care is covered since the Emergency Medical Treatment and Labor Act, passed in 1996, prohibited medical professionals from refusing care to anyone—regardless of immigration status or other factors—who was medically unstable due to an “emergency medical condition,” defined as “a condition manifesting itself by acute symptoms of sufficient severity… such that the absence of immediate medical attention could reasonably be expected to result in placing the person’s health… in serious jeopardy, serious impairment to bodily functions, or serious dysfunction of bodily organs.”9 Most recently, the 2010 Affordable Care Act forbid payment for the care of non-citizens and excludes undocumented patients from the healthcare marketplaces.10

These acts left states with some variability in how to interpret and apply the law regarding chronic RRT for undocumented immigrants. Because they could not use federal funding for chronic disease in undocumented immigrants, some states chose to use state funding by emergency Medicaid to provide chronic outpatient dialysis for these patients.11 These states include Arizona, California, Colorado, Washington D.C., Illinois, Massachusetts, Minnesota, New York, North Carolina, and Washington, although policies can vary from institution to institution.12,13 Other states depend on a variety of approaches including the emergent dialysis approach or a hybrid model (Table 1).6,14 Changes to legislation have occurred in some states. However, the lack of a consistent federal policy leads to confusion and frequent legal disputes.15,16

Table 1.

Approaches to Providing Renal Replacement for Undocumented Immigrants

| Approach | Emergent approach | Hybrid model | Chronic care |

|---|---|---|---|

| Criteria | Admitting patients for life-threatening emergent indication for therapy only | Admitting patients for regular inpatient therapy based on hospital criteria | Patients provided with outpatient dialysis chair |

| Access | Temporary vascular access with dialysis catheter | Dialysis access variable depending on hospital and patient | Dialysis via arteriovenous fistula (AVFs) |

| Disposition | May require 2–3 consecutive days of dialysis | Dependent on availability of services; generally discharged on the same day | Dialysis consistently provided three times weekly |

Sixty-five percent (n = 642) of nephrologists surveyed nationwide stated that they care for undocumented patients with ESRD and this problem is becoming more prevalent.12,15 Dr. Barry Straube, Chief Medical Officer of the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, wrote in 2009, “Clearly we need more data and information to best define options and reform national and state policies.”17 This review aims to describe the medical, ethical, and financial implications of current models of RRT for undocumented immigrants. This paper will review all original studies published on this issue. Special models including transplant and peritoneal dialysis are also reviewed, as well as suggestions by the authors of this analysis.

METHODS

A search of the English literature was conducted on PubMed, Ebscohost Biomedical Reference Collection, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), and Trip databases on 1 March 2017. No beginning date was set for this search.

In PubMed, the following Medical Subject Headings were used: “Kidney failure, chronic,” “Dialysis,” “Renal dialysis,” “Kidney transplantation,” “Renal replacement therapy,” “Undocumented immigrants,” “Emigrants and immigrants,” “Emigration and immigration,” In CINAHL, the medical headings were “Kidney failure, chronic,” “Dialysis,” “Dialysis patients,” “Hemodialysis,” “Kidney transplantation,” and “Immigrants, illegal.” Additional keywords used in Trip and PubMed included “End stage renal disease (ESRD),” “End stage kidney disease,” “chronic renal failure,” “end stage renal failure,” “kidney transplant,” “dialysis,” “hemodialysis,” “immigrants,” “migrants,” “aliens,” “illegal,” “unauthorized,” and “undocumented.” All relevant abstracts obtained by this search were searched in Google Scholar using the “cited by” and “related articles” features in order to ensure the comprehensive nature of this search.

Only peer-reviewed original studies addressing undocumented immigrants’ relation to renal replacement therapy, kidney transplantation, or other treatment for ESRD were included. Case studies, editorials, commentaries, and news articles were excluded. Articles addressing undocumented immigrant’s access to healthcare in general or minority use of renal services were not included. Due to the heterogenous design of studies with variable outcomes and measures, a systematic review was not deemed possible.

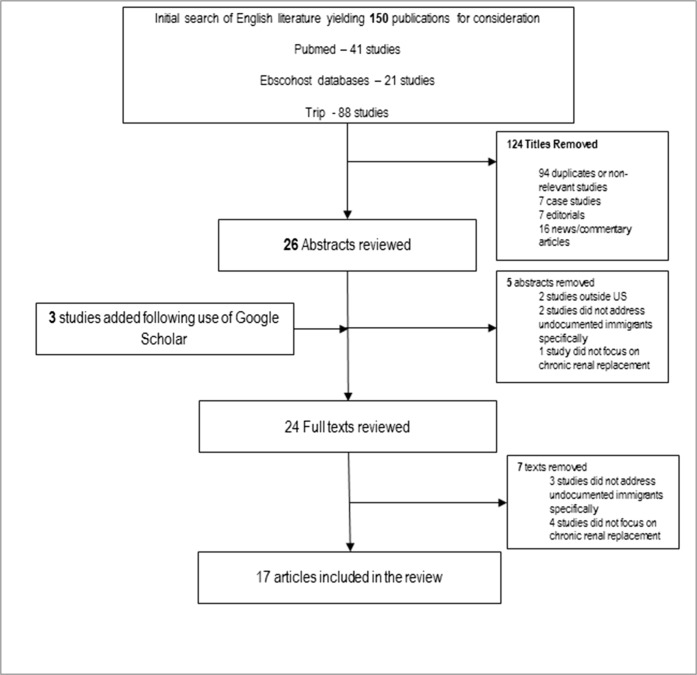

The search yielded 150 results, of which 94 were duplicates or non-relevant titles. Seven were case studies, seven were editorials, and sixteen were news/commentary articles. After use of Google Scholar, an additional 3 results were added. After review of abstracts and relevant full texts, 17 articles were included for the purposes of this review (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Methodology used in article selection.

RESULTS

Demographics

The results are organized in Table 2. One studies nephrologists and administrators, 2 study transplant recipients, and the other 14 study hemodialysis recipients. There are no direct studies of peritoneal dialysis in this population. There is a geographic predominance for TX, a state with very high undocumented immigrant population. Articles based in NY, CA, CO, AZ, and NM are also featured in multiple articles. Multiple articles are by the same author and many by the same state, indicating some overlap of patient populations. All of these studies were published after 2004, with 14 (82%) being published after 2009.

Table 2.

List of Studies Included in the Review

| Author (reference) | Type | Year | Location | Sample size | Sample type |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ahmed et al. 18 | Retrospective cohort | 2016 | TX | 88 | Undocumented immigrants with ESRD |

| Cervantes et al. 6 | Cross-sectional survey | 2017 | CO | 20 | Undocumented immigrants with ESRD |

| Cervantes et al. 19 | Retrospective Cohort study | 2018 | CO, TX, CA | 211 | Undocumented immigrants with ESRD |

| Coritsidis et al. 7 | Retrospective cohort study and cross-sectional survey | 2004 | NY | 278 | Dialysis patients |

| Dubard and Massing 20 | Descriptive analysis | 2007 | NC | 48,391 | Individuals with services covered by emergency Medicaid |

| Hogan et al. 21 | Cross-sectional survey | 2017 | TX | 88 | Undocumented immigrants with ESRD |

| Hurley et al. 15 | Cross-sectional survey | 2009 | National | 990 | Nephrologists |

| Linden et al. 22 | Cross-sectional survey | 2012 | NY | 45 | Undocumented immigrants with ESRD |

| Madden And Qeadan 16 | Case-control study | 2017 | New Mexico | 759 cases | Emergent dialysis recipients through hospital ED |

| McEnhill et al. 23 | Retrospective cohort study | 2015 | CA | 304 | Pediatric kidney transplant recipients |

| Raghavan 24 | Retrospective cohort | 2012 | TX | 140 | Undocumented immigrants with ESRD |

| Raghavan 25 | Descriptive analysis | 2017 | TX | > 100 | Undocumented immigrants with ESRD |

| Raghavan and Sheikh-Hamad 26 | Retrospective cohort | 2011 | TX | 186 | Undocumented immigrants with ESRD |

| Sheikh-Hamad et al. 14 | Retrospective cohort study and cross-sectional survey | 2007 | TX | 35 | Undocumented immigrants with ESRD |

| Shen et al. 27 | Retrospective cohort study | 2018 | National | 346 | Medicaid patients who received kidney transplant (1990–2011) |

| Sher et al. 11 | Retrospective case series | 2017 | IN | 19 | Undocumented immigrants with ESRD |

| Weaver et al. 28 | Retrospective case series | 2012 | IN | 6 | Dialysis patients without a dialysis home |

Models of Care

There are several models for chronic renal replacement therapy for undocumented immigrants described in the literature (Table 1). At one extreme, there is the emergent dialysis approach: patients are only admitted in true life-threatening emergencies, and commonly require intensive care and dialysis therapy for multiple days through a temporary vascular catheter which is removed on discharge. At the other end, there is chronic care, where patients are treated in the same way as documented insured patients. Finally, most healthcare centers use a hybrid model, which utilizes a hospital to provide “inpatient” dialysis services to patients admitted for less than a day somewhat regularly, depending on resource availability and patient need.14,19,24 Hybrid models typically have the patients arrive at the emergency department two or three times per week. These patients are “admitted” to general medicine or nephrology services to go to inpatient dialysis units, where they undergo hemodialysis by whatever vascular access they have available. They are then discharged with plans to return in 3–4 days.

Medical Considerations

Initiation of RRT

Undocumented immigrants present to medical care later than documented patients.7 While standard of care is to initiate dialysis when the GFR falls below 15, it is frequently delayed in undocumented immigrants until the patient requires an emergency treatment.24 This delay of care may be due to the negative impact of emergency dialysis on these patients’ ability to work and live.24 The documentation status of these patients also impacts their access to renal specialists, leading to inconsistent pre-dialysis renal care.7,24

Arteriovenous access is a problem for undocumented patients. For undocumented patients, dialysis is more frequently through catheters instead of AVFs, which can be more dangerous for patients.24 In some cases, the decision to have an AV fistula placed is largely based on the charity of vascular surgeons.24 Other centers have systems in place for more consistent access as AV fistulas are associated with lower costs and better outcomes; however, it is less common for them to be present where emergency dialysis is practiced.14,19,22

Complications of RRT

Complications of RRT in undocumented patients are a result of the differences in their care. Uremic pericardial effusions, nephrogenic ascites, and dialysis disequilibrium syndrome are seen frequently in one center.24 Undocumented patients are also at risk for increased mortality due to inadequate dialysis dosing.11,24 Emergent approach dialysis resulted in a higher number of transfusions while chronic care was associated with a higher number of EPO treatments.14 Undocumented patients also need increased medical management of the interdialytic period. This can include adding medications that have not been proven, inconsistent dosing of expensive medications such as erythropoietin, and supplementation with over the counter medicines. 18,24 When these medications are lost, the consequences can be dangerous.23

Quality of life is significantly lower in undocumented patients undergoing emergent dialysis.6,14,21 Undocumented immigrants undergoing emergent dialysis reported increased physical pain and a lower level of function despite having an increased satisfaction with care compared to those undergoing chronic care.14 In one study, many patients in a center that practices emergent dialysis report the difficulties of waiting for symptom accumulation, specifically debilitating shortness of breath. Patients also described the anxiety of impending death and the effects of repeated cardiopulmonary resuscitation when they presented too late. These consequences of emergent dialysis negatively impacted patients’ ability to work and survive among undocumented immigrants.6

Increased Utilization and Mortality

These complications are associated with increased length of stay, more ICU days, more ED visits, and increased mortality.7,11,14,19 Exceptions to these problems are rare, although one study comparing emergent dialysis and routine inpatient dialysis found no significant differences in 6 patients over a period of 3 months.28 However, in a large, multi-center study, emergent dialysis was associated with a 10-fold increase in acute care days, with only a 3-fold decrease in ambulatory care visits.19 Length of stay for initial dialysis was approximately 3 days longer in undocumented patients.7 In one study, emergent dialysis was associated with a 5-day increase in ICU stay, a 12-fold increase in the number of admissions, and a 26-fold increase in the number of emergency room visits.14 These complications are associated with a 5- to 14-fold increase in mortality in undocumented patients undergoing emergency dialysis.19

Physician Perspectives

In a national survey, most nephrologists believed undocumented immigrants with ESRD have inadequate access to healthcare and were frustrated by the impossibility of obtaining outpatient long-term dialysis, unavailability of transplantation, and the growing prevalence of undocumented patients with ESRD.15 Physicians do not support the idea that undocumented immigrants coming to the USA for the purpose of medical care, or switch states for the purpose of consistent outpatient treatment; most studies support that undocumented patients are unaware of their diagnoses prior to immigration and do not relocate to other states for access to better care. 7,26,27 One physician surveyed by Hurley et al. stated, “I will provide dialysis to all those who medically require it. However, the absence of resources to fund this can severely tax my practice… the dialysis unit and hospital.” Others stated, “When they become adults, no one will accept them . . . . . Eventually, our pediatric dialysis unit in a children’s hospital will have a dialysis program filled with adult, undocumented patients.” As well as, “I dialyze these patients in the hospital dialysis units because the medical directors of the outpatient units won’t accept them.”15

One common ethical problem is forcing providers to decide who gets care by declaring when an undocumented patient qualifies as “emergent.” This burden can fall on emergency room physicians, nephrologists, or even triage nurses and social workers. 6,24,28 Healthcare professionals are also faced with providing substandard care with poor dialysis access and non-existent outpatient care, and deciding how inpatient dialysis chairs should be distributed. 6,24 While many undocumented patients are aware that this treatment is below the current standard of care but express gratitude to providers and healthcare systems for any treatment.6

Financial Considerations

Burden on the Healthcare System

Under the current system, inadequate reimbursement for undocumented immigrants is a problem.11,15,25 There are substantial variations in the estimations of cost to the hospital, ranging from $285,000 annually for one undocumented patient to $1 million annually for 20 undocumented patients.19,27 Undocumented patients were associated with an increase of $5000 per admission.7 Emergent dialysis for undocumented immigrants is estimated to cost US $383 million annually.22 This can lead to hospitals changing their treatment formula to decrease the burden of these patients.11,28 One nephrologist said, “[T]he absence of resources to fund this can severely tax my practices...the dialysis unit and the hospital.”15 While one study did show improvement in the reimbursement to cost ratio with emergency dialysis, this was with a small sample size and excluded physician fees, which would likely be higher due to multiple physicians being involved in the care of emergent dialysis patients.11

Of emergency Medicaid expenditures in North Carolina, renal failure was the third highest diagnostic group after pregnancy and intracranial injury.29 In Colorado, ESRD patients without access to scheduled dialysis were found to have the highest per capita costs and be “superutilizers” and undocumented immigrants use the ED for dialysis far more than controls.6,22 One study did find a decrease in cost by using emergent dialysis compared to regularly scheduled inpatient dialysis; however, it had a small sample size (n = 6) and study period (t = 3 months).28 In one center, 25 patients present to the ED daily for emergent dialysis, depending on availability, approximately 15 are dialyzed and the remainder sent home; at least one patient is admitted to the hospital every day for inpatient management of a dialysis-related condition.24 Different models for streamlining emergent dialysis or lengthening the interdialytic period have been developed but lack widespread implementation.18,24,28

Forced Unemployment

Undocumented immigrants are employed at a very high rate for ESRD patients.7,22 In some cases, twice as many undocumented patients are employed compared with documented ESRD patients.7 The USA relies on this population for work and social contributions, but inadequate dialysis impedes their productive role in society.14,21 Many of them are contributing or have contributed substantially to the Medicare and social security system they are unable to access.14,26 However, in one survey, 79.5% (n = 35) of undocumented dialysis patients reported their unemployment was a direct result of the burden of obtaining emergent dialysis.21 In another study, 90% (n = 43) of undocumented patients receiving emergency-only dialysis were employed prior to starting renal replacement; however, only 14% (n = 6) were able to continue while on emergency dialysis.26

Special Considerations for Other Modes of Care

Transplant

The Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network says organ allocation should not be restricted based on immigration status.23 The barrier to accessing transplants for undocumented immigrants is largely financial.27 In some areas, 10% of organs come from undocumented donors, but they receive less than 1% of donated organs. 23,27 Many undocumented patients are younger and healthier than documented controls and report willing living donors.22 Transplantation saves money compared with outpatient renal replacement after approximately 1.5–2.7 years.22 One California study showed that in pediatric transplant recipients, undocumented immigrants had a lower risk of allograft failure. However, once patients reached 21 years of age, they no longer qualified for state-sponsored funding to help pay for immunosuppressants and one in five lost their grafts.23 Comparably insured undocumented adults have similar outcomes to US citizens.27 One article estimates savings of $321,000 per transplant patient in New York.22 Despite future savings to taxpayers, transplantation out-of-pocket costs for the uninsured are prohibitively expensive.22,23,26

Peritoneal Dialysis

Peritoneal dialysis is one of the most financially sustainable models.24 It is the treatment of choice in Mexico; however, it is frequently denied for undocumented immigrants in the USA for reimbursement issues and concerns about patient adherence.7,24 When outpatient dialysis is covered by emergency Medicaid, peritoneal dialysis in undocumented immigrants has been successful.7

DISCUSSION

This comprehensive literature review showed several concerning findings. First, emergent dialysis is associated with potentially avoidable life-threatening complications. This model is associated with increased complications, ICU days, ED utilization, and hospital admissions; this is likely secondary to the delay in treatment, inadequate AV access, and inconsistent dialysis associated with this model increase complications, ICU days, ED utilization, and hospital admissions for undocumented immigrants. Most importantly, these complications significantly increase patient mortality.

Second, while physicians agree it is their obligation to treat the sick, they are hindered by inadequate resources and different priorities by administrators and governments. This burden of care unjustly falls on healthcare providers with little say in immigration and financial policy and the burden of payment on state residents in those states with a high undocumented population. The commentary literature agrees that medical services ought not to act as proponents of deportation; this could increase patient nonadherence due to fear of forced repatriation.5,9,20 If repatriation takes place, most undocumented immigrants are no longer eligible for insurance in their home countries, and those countries may not provide chronic dialysis to the indigent.30 Adjusted mortality is higher in Mexico compared with uninsured US Hispanic patients.15 The 90-day survival for patients starting renal replacement therapy in Mexico is estimated at 39%, compared with 90% in the USA.26 In one Mexican state, while access is, “[A]lmost universal for the insured population, it is severely restricted for the poor.”31

Finally, the system of emergent dialysis in the UA is not financially efficient. There is a drain of resources created by low-value care with the repeated laboratory tests, emergency department utilization, temporary access catheters, and other unnecessary spending. One article suggests that the cost of $260 million to cover all undocumented immigrant renal replacement pales in comparison with the $11–15 billion contributed in social security payroll taxes each year by undocumented residents, $2.4 billion of which goes to Medicare. 20,32 One study stated that the annual hospital expense was $212,000 per emergent dialysis patient compared with $55,000 per chronic care.33 Another describes a day 30 undocumented patient arrived for emergent dialysis by saying, “It virtually paralyzed their dialysis services.”8 However, healthcare providers are finding creative ways to fund these patients. Private insurance obtained off the federal exchange can play a role for undocumented immigrants who can afford this.21 Social work and case management can play a valuable role in finding funding for patients and coordinating their care.11,28 However, these measures are ultimately only stopgaps. Immigration reform, while currently the subject of intense political interest, is unlikely to stop the increase of patients needing renal replacement due to an aging existing undocumented population.

Ultimately, the evidence suggests that emergent dialysis is a dangerous, financially irresponsible practice that is not supported by physicians. The Ethics Committee of the Society for General Internal Medicine (SGIM) established the Coalition for Kidney Care of Non-Citizens (CKCNC) in 2013, which formulated a position statement in 2015 (Table 3). This position statement is intended to be the beginning of a process to develop a formal policy and advocate on a national scale for these vulnerable patients.34 There are many other avenues by which healthcare professionals can advocate locally and nationally for their patients. The SGIM advocacy website (https://www.sgim.org/communities/advocacy) has tools for local and federal advocacy, and the annual “Hill Day” is a focus for the organization to concentrate advocacy efforts. The American Society of Nephrology (ASN) also has a fairly prominent advocacy wing. Their website (https://www.asn-online.org/policy/) contains tools for advocacy and also events that are specifically focused on advocating for patients with kidney disease. The ASN also provides state-specific fact sheets regarding kidney disease, which can be helpful in local advocacy. The CMS director asked for more information in 2009, and 14 new studies have been published since this call (Table 2), but now the information must be put to good use in reforming the current systems.17

Table 3.

CKCNC Position Statement (2015)

| Preamble | The right to health care is an internationally recognized human right due to its fundamental impact on the individual’s abilities to participate in the political, social, and economic life of society. This statement focuses specifically on the undocumented population of immigrants, as this is a topic of debate currently in the United States and a growing problem for health care systems across the country. |

| 1 | There is a collective ethical obligation amongst health care professionals and health care systems to ensure access to standard medical care (including as an example maintenance dialysis and transplant for patients with end-stage kidney disease) to individuals regardless of citizenship status, ethnic origin, nationality, native language, legal or social standing, or economic means.1,2 |

| 2 | Physicians should, individually and collectively, advocate for public and charitable funding programs to eliminate financial barriers to medical care. All physicians should fulfill their social responsibility for delivering high-quality health care to those without the resources to pay.2 |

| 3 | Physicians should uphold patient confidentiality and should not report non-medical information about the documentation status of undocumented non-citizens to the authorities. |

| 4 | Physicians should, individually and collectively, work with all relevant stakeholders including patients, policy makers, health insurers, and health care systems to ensure, within the best of their abilities, that health resources are justly distributed amongst all. |

| References |

1Adapted from the Declaration of Geneva http://www.wma.net/en/30publications/10policies/g1/ 2Adapted from the American Medical Association’s Health and Ethics Policy H-160.987 Access to Medical Care 3AMA Principle 3-6b: All health care facilities and health professionals should fulfill their social responsibility for delivering high-quality health care to those without the resources to pay. |

CONCLUSION

This review shows the available literature, both quantitative and qualitative, that overwhelmingly supports the need for advocacy. Provision of renal replacement therapy ought to be morally equitable, financially sustainable, and medically safe for all populations. The emergent and most hybrid models meet none of these three criteria. Innovative solutions at the level of the individual center exist and can ameliorate some of these outcomes, but these are still inadequate to justify widespread implementation. Maintenance hemodialysis is a cost-effective, humane option. Improved access to transplantation and peritoneal dialysis on a national level is a good initial step, but ultimately the questions of reimbursement for other forms of care must be addressed, especially for states and centers that handle a high burden of these vulnerable patients. It will require collaboration between government, both federal and state; healthcare facilities including hospitals, clinics, and practitioners; and kidney care organizations such as DaVita and Fresenius. Without this planning and partnership, the unethical, unsustainable, and dangerous current systems will remain in place.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Dr. John Brouillette, Dr. Denyse Thornley-Brown, and Dr. Seema Biswas for their helpful comments and review. They would also like to thank Ms. Elizabeth Laera, AHIP, for help in formulating the literature search.

Authors’ Contributions

Research idea and study design: NTD, CO; data acquisition: NTD; data analysis/interpretation: NTD; supervision or mentorship: CO. Each author contributed important intellectual content during manuscript drafting or revision and accepts accountability for the overall work by ensuring that questions pertaining to the accuracy or integrity of any portion of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Prior Presentations

Nothing to declare

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Rettig RA. Special treatment—the story of Medicare’s ESRD entitlement. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(7):596–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1014193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alexander S. They decide who lives, who dies. Life. 1962;9:102. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Levine C. The Seattle ‘God Committee’: A Cautionary Tale. [internet] Health Affairs Blog, 2009. Accessed from http://healthaffairs.org/blog/2009/11/30/the-seattle-god-committee-a-cautionary-tale/ on 6/14/2019

- 4.Saran R, Robinson B, et al. US renal data system 2016 annual data report: epidemiology of kidney disease in the United States. Am J Kidney Dis. 2017;69(3):A7–8. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2016.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Campbell GA, Sanoff S, Rosner MH. Care of the undocumented immigrant in the United States with ESRD. Am J Kidney Dis. 2010;55(1):181–91. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2009.06.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cervantes L, Fischer S, et al. The Illness Experience of Undocumented Immigrants With End-stage Renal Disease. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(4):529–35. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.8865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coritsidis GN, Khamash H, et al. The initiation of dialysis in undocumented aliens: the impact on a public hospital system. Am J Kidney Dis. 2004;43(3):424–432. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2003.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gupta S, Fenves AZ. Dialysis in the undocumented: The past, the present, and what lies ahead. InSeminars in Dialysis 2017. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Kuruvilla R. R. Health care for undocumented immigrants in Texas: past, present, and future. Tex Med. 2014;110(7):e1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Renal Physicians Association. RPA position on uncompensated renal-related care for citizens and non-citizens 2009.

- 11.Sher SJ, Aftab W, et al. Healthcare outcomes in undocumented immigrants undergoing two emergency dialysis approaches. Clin Nephrol. 2017;88(10):181. doi: 10.5414/CN109137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McKinney M. Care of Undocumented Immigrants with ESRD: A Consistent Federal Policy is Needed, Experts Say. Nephrol Times. 2010;3(2):9–11. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schrag WF. Insurance coverage for unauthorized aliens confusing and complex. Nephrol News Issues. 2015;29(8):12–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sheikh-Hamad D, Paiuk E, Wright AJ, Kleinmann C, Khosla U, Shandera WX. Care for immigrants with end-stage renal disease in Houston: a comparison of two practices. Tex Med. 2007;103(4):54–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hurley L, Kempe A, et al. Care of undocumented individuals with ESRD: a national survey of US nephrologists. Am J Kidney Dis. 2009;53(6):940–9. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2008.12.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Madden EF, Qeadan F. Dialysis Hospitalization Inequities by Hispanic Ethnicity and Immigration Status. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2017;28(4):1509–21. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2017.0130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Straube BM. Reform of the US healthcare system: care of undocumented individuals with ESRD. Am J Kidney Dis. 2009;53(6):921–4. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2009.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ahmed S, Guffey D, Minard C, Workeneh B. Efficacy of loop diuretics in the management of undocumented patients with end-stage renal disease. Am J Emerg Med. 2016;34(8):1552–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2016.05.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cervantes L, Tuot D, Raghavan R, Linas S, Zoucha J, Sweeney L, Vangala C, Hull M, Camacho M, Keniston A, McCulloch CE. Association of emergency-only vs standard hemodialysis with mortality and health care use among undocumented immigrants with end-stage renal disease. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(2):188–95. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.7039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Slifkin RF, Charytan C. Ethical Issues Related to the Provision or Denial of Renal Services to Non-citizens. Semin Dial. 1997;10(3):173–175. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-139x.1997.tb00483.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hogan AN, Fox WR, Roppolo LP, Suter RE. Emergent Dialysis and its Impact on Quality of Life in Undocumented Patients with End-Stage Renal Disease. Ethn Dis. 2017;27(1):39. doi: 10.18865/ed.27.1.39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Linden EA, Cano J, Coritsidis GN. Kidney transplantation in undocumented immigrants with ESRD: a policy whose time has come? Am J Kidney Dis. 2012;60(3):354–9. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2012.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McEnhill ME, Brennan JL, et al. Effect of immigration status on outcomes in pediatric kidney transplant recipients. Am J Transplant. 2016;16(6):1827–33. doi: 10.1111/ajt.13683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Raghavan R. When access to chronic dialysis is limited: one center’s approach to emergent hemodialysis. Semin Dial. 2012;25(3):267–271. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-139X.2012.01066.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Raghavan R. New opportunities for funding dialysis-dependent undocumented individuals. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017;12(2):370–5. doi: 10.2215/CJN.03680316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Raghavan R, Sheikh-Hamad D. Descriptive analysis of undocumented residents with ESRD in a public hospital system. Dialysis & Transplantation. 2011;40(2):78–81. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shen JI, Hercz D, Barba LM, Wilhalme H, Lum EL, Huang E, Reddy U, Salas L, Vangala S, Norris KC. Association of citizenship status with kidney transplantation in medicaid patients. Am J Kidney Dis. 2018;71(2):182–90. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2017.08.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Weaver CS, Myers IJ, Huffman G, Vohito R, Herceg D. An analysis of a case manager-driven emergent dialysis program. Prof Case Manag. 2012;17(1):24–8. doi: 10.1097/NCM.0b013e31822f6042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.DuBard CA, Massing MW. Trends in emergency Medicaid expenditures for recent and undocumented immigrants. Jama. 2007;297(10):1085–92. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.10.1085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rodriguez RA. The dilemma of undocumented immigrants with ESRD. Dialysis & Transplantation. 2010;39(4):141–3. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Garcia-Garcia G, Monteon-Ramos JF, Garcia-Bejarano H, Gomez-Navarro B, Reyes IH, Lomeli AM, Palomeque M, Cortes-Sanabria L, Breien-Alcaraz H, Ruiz-Morales NM. Renal replacement therapy among disadvantaged populations in Mexico: a report from the Jalisco Dialysis and Transplant Registry (REDTJAL) Kidney Int. 2005;68:S58–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2005.09710.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cervantes L, Grafals M, Rodriguez RA. The United States Needs a National Policy on Dialysis for Undocumented Immigrants With ESRD. Am J Kidney Dis. 2018;71(2):157–9. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2017.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Paiuk E, Kleinmann C, Sheikh-Hamad D, Shandera W. Denying chronic dialysis services to non-documented ESRD patient: Is it fiscally wise? J Am Soc Nephrol. 2002;13:397A–398A. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Society of General Internal Medicine, Ethics Sub-Committee. From the Society. [internet] October 2015, [accessed 6/14/2019] available from https://www.sgim.org/File%20Library/SGIM/Resource%20Library/Forum/2015/SGIMOct2015_07.pdf