Abstract

Background

Comparative effectiveness of early rheumatoid arthritis (RA) treatments remains uncertain.

Purpose

Compare benefits and harms of biologic drug therapies for adults with early RA within 1 year of diagnosis.

Data Sources

English language articles from the 2012 review to October 2017 identified through MEDLINE, Cochrane Library and International Pharmaceutical Abstracts, gray literature, expert recommendations, reference lists of published literature, and supplemental evidence data requests.

Study Selection

Two persons independently selected studies based on predefined inclusion criteria.

Data Extraction

One reviewer extracted data; a second reviewer checked accuracy. Two independent reviewers assigned risk of bias ratings.

Data Synthesis

We identified 22 eligible studies with 9934 participants. Combination therapy with tumor necrosis factor (TNF) or non-TNF biologics plus methotrexate (MTX) improved disease control, remission, and functional capacity compared with monotherapy of either MTX or a biologic. Network meta-analyses found higher ACR50 response (50% improvement) for combination therapy of biologic plus MTX than for MTX monotherapy (relative risk range 1.20 [95% confidence interval (CI), 1.04 to 1.38] to 1.57 [95% CI, 1.30 to 1.88]). No significant differences emerged between treatment discontinuation rates because of adverse events or serious adverse events. Subgroup data (disease activity, prior therapy, demographics, serious conditions) were limited.

Limitations

Trials enrolled almost exclusively selected populations with high disease activity. Network meta-analyses were derived from indirect comparisons relative to MTX due to the dearth of head-to-head studies comparing interventions. No eligible data on biosimilars were found.

Conclusions

Qualitative and network meta-analyses suggest that the combination of MTX with TNF or non-TNF biologics reduces disease activity and improves remission when compared with MTX monotherapy. Overall adverse event and discontinuation rates were similar between treatment groups.

Registration

PROSPERO (available at http://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/display_record.php?ID=CRD42017079260).

INTRODUCTION

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is an autoimmune systemic inflammatory disease affecting more than 1 million Americans and characterized by synovial inflammation, which can lead to progressive bone erosion, joint damage, and disability.1 For patients with early RA (≤ 1 year of disease),2 guidelines recommend early treatment with the goal of remission or low disease activity.3, 4 Available therapies for RA include corticosteroids, conventional synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (csDMARDs), tumor necrosis factor (TNF) and non-TNF biologics, targeted synthetic DMARDs (tsDMARDs), and biosimilars. Over the past two decades, biologics have become an important treatment option for established RA. However, clinicians face the challenge around biologic use in early RA.

Biologics commonly used for RA treatment include TNF biologics (adalimumab, certolizumab pegol, etanercept, golimumab, infliximab) and non-TNF biologics (abatacept, rituximab, tocilizumab, and sarilumab). Experts and guideline groups support using csDMARDs, often methotrexate (MTX), as the first line-therapy.3, 4 Despite recommendations, advocates encourage early biologic use to induce remission.5, 6

In a 2012 systematic review, evidence comparing early RA treatment options was limited.7 No studies investigated efficacy, effectiveness, and harms among subgroup populations. Recently, information from clinical trials of four biosimilar drugs (ADA-atto, IFX-dyyb, IFX-abda, ETN-szzs), a tsDMARD (tofacitinib), and one non-TNF biologic (sarilumab) have become available. Additionally, studies continue to be published on established therapies. Given this uncertainty, the Agency of Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) and the Patient Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) commissioned a systematic review to compare effectiveness and harms of RA drugs in patients with early RA. This paper focuses on comparisons of benefits and harms of treatments in early RA involving biologics.

METHODS

The full technical report describes the study methods in detail8 and the protocol was registered at PROSPERO (http://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/display_record.php?ID=CRD42017079260). In a comprehensive synthesis of the evidence, we included data from studies dating back to June 2006, identified in the 2012 review on this topic7 and through an updated literature search.

Data Sources

A professional research librarian searched MEDLINE, Cochrane Library, Embase, and International Pharmaceutical Abstracts from January 2011 to October 5, 2017. We re-reviewed studies included in the 2012 review,7 supplemental evidence (data received through the AHRQ Web site and a Federal Register notice), and reference lists of included studies and recent reviews. We also searched the following sources for unpublished studies: ClinicalTrials.gov, World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform, and New York Academy of Medicine’s Grey Literature Index.

Study Selection

We included study populations defined as early RA by the authors if the diagnosis was ≤ 1 year in the past (Table 1 presents inclusion and exclusion criteria). Two reviewers independently reviewed titles and abstracts using abstrackr9 and full-text articles for eligibility. To assess efficacy regarding disease activity, response, remission, radiographic progression, and functional capacity, we included head-to-head controlled trials and prospective cohort studies comparing any of the therapies. In addition, we included placebo- and MTX-controlled trials for network meta-analyses (NWMA). For adverse events, we abstracted data on overall adverse events, overall study discontinuation, discontinuation attributed to adverse events or toxicity, patient adherence, and any serious adverse events as defined by the FDA.10 For specific adverse events (that were not serious adverse events), we focused on those most commonly reported according to their FDA-approved labels.

Table 1.

Eligibility Criteria

| PICOTS | Inclusion | Exclusion |

|---|---|---|

| Population |

Adult outpatients 18 years of age or older with a diagnosis of early RA, defined as 1 year or less from disease diagnosis; studies with mixed populations if > 50% of study populations had an early RA diagnosis Subpopulations by age, sex or gender, race or ethnicity, disease activity, prior therapies, concomitant therapies, and other serious conditions |

Adolescents and adult patients with disease greater than 1 year from diagnosis; inpatients |

| Intervention |

TNF biologics: adalimumab, certolizumab pegol, etanercept, golimumab, infliximab Non-TNF biologics: abatacept, rituximab, sarilumab, tocilizumab |

Anakinra is excluded because, although it is approved for RA, clinically it is not used for this population61; non-biologic therapies for RA |

| Comparator |

For head-to-head RCTs, head-to-head nRCTs, and prospective, controlled cohort studies: any active intervention listed above For additional observational studies of harms and among subgroups: any active intervention listed above For double-blinded, placebo-controlled trials for network meta-analysis: placebo |

All other comparisons, including active interventions not listed above; no comparator; dose-ranging studies that are not comparing two different interventions |

| Outcomes |

Disease activity, response, remission, radiographic joint damage Functional capacity, quality of life, patient-reported outcomes Overall risk of harms, overall discontinuation, discontinuation because of adverse effects, risk of serious adverse effects, specific adverse effects*, patient adherence |

All other outcomes not listed |

| Timing | At least 3 months of treatment | < 3 months treatment |

| Settings | Primary, secondary, and tertiary care centers treating outpatients | Facilities treating inpatients only |

| Country setting | Any geographic area | None |

| Study designs |

Study designs include head-to head RCTs and nRCTs; prospective, controlled cohort studies (N > 100); double-blinded, placebo-controlled trials for network meta-analysis; and SRs only to identify additional references For studies of harms—i.e., overall and among subgroups, study designs also included any other controlled observational study (e.g., cohort, case-control) (N > 100) |

All other designs not listed |

| Publication language | English | Languages other than English |

FDA US Food and Drug Administration; KQ key question; N number; nRCT nonrandomized controlled trial; PICOTS population, intervention/exposure, comparator, outcomes, time frames, country settings, study design; RA rheumatoid arthritis; RCT randomized controlled trial; SR systematic review; TNF tumor necrosis factor

*Most commonly reported according to their FDA-approved labels—rash, upper respiratory infection, nausea, pruritus, headache, diarrhea, dizziness, abdominal pain, bronchitis, leukopenia, and injection site reactions

Data Extraction and Risk of Bias Assessment

Trained reviewers abstracted each study using a structured, pilot-tested form and a senior reviewer evaluated accuracy. To assess the risk of bias (ROB), we adapted the Cochrane Risk of Bias tool11 for randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and used the Risk of Bias in Non-randomised Studies of Interventions (ROBINS-I) tool12 for nonrandomized controlled studies.

Data Synthesis and Analyses

We planned to conduct pairwise analysis when possible and NWMAs to estimate the indirect treatment effects. Criteria for eligible studies for NWMA included1 no failed prior treatment attempt with MTX2, treatment doses within FDA-approved ranges3, 12-month follow-up, and4 double-blinded RCTs of low or medium ROB. Head-to-head and placebo-controlled RCTs were eligible for NWMA; however, we did not find any eligible placebo-controlled trials in a population with early RA. We considered NWMA for American College of Rheumatology 50% improvement (ACR50), Disease Activity Score (DAS) remission, radiographic joint damage, all study discontinuations, and discontinuations attributed to adverse events.

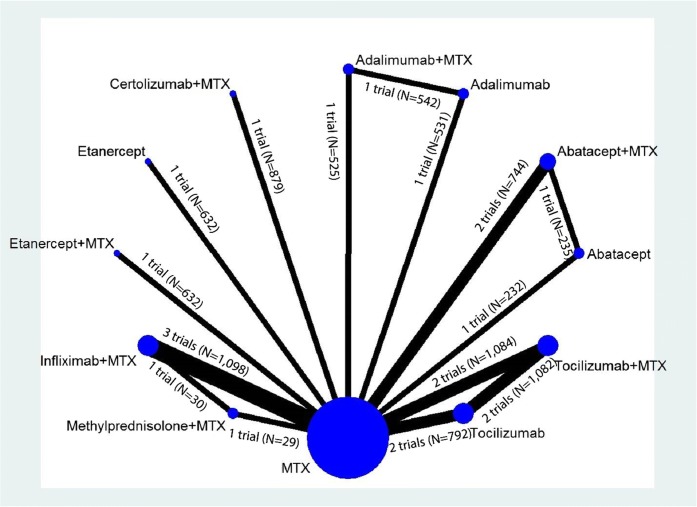

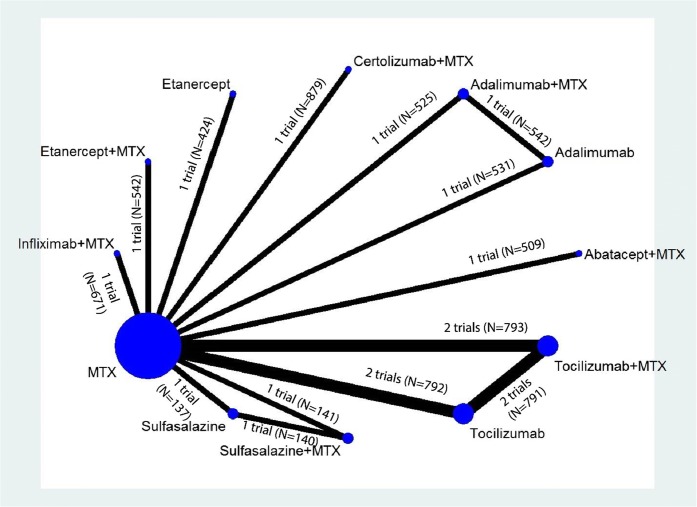

We ran NWMAs using a multivariate, random effects meta-regression model with restricted maximum likelihood for variance estimation.13 Models were fit using the Stata “network” package14 an updated versions of the “mymeta” package which accounts for multi-arm trials. The network structure for outcomes was mostly “star-shaped,” indicating a dearth of head-to-head studies directly comparing interventions (see Figs. 1 and 2, low strength of evidence). Most effect estimates, therefore, were derived from indirect comparisons relative to MTX rather than mixed treatment comparisons. For closed loops, we tested the transitivity assumption by examining loop-specific consistency between direct and indirect effects using network side splits and global consistency by comparing a model assuming consistency with a model not assuming consistency (i.e., inconsistency model). When the global Wald test indicated no significant differences between the consistency and inconsistency models,15 and no significant differences in estimates based on side splits, we presented consistency model estimates.

Figure 1.

Network diagram for network meta-analysis of ACR50 response rates. MTX, methotrexate; N, number of patients.

Figure 2.

Network diagram for network meta-analysis of change from baseline in radiographic joint damage score. MTX, methotrexate; N, number of patients.

Strength of Evidence

We evaluated strength of evidence for each comparison based on the guidance established for AHRQ’s EPC Program as high, moderate, and low or insufficient.16 We graded strength of evidence for the following outcomes: disease activity, response, radiographic joint damage, functional capacity, discontinuation because of adverse events, and serious adverse events.

Role of the Funding Source

This topic was nominated and funded by PCORI in partnership with AHRQ. The AHRQ Contracting Officer’s Representative and PCORI program officers provided comments on the protocol and full evidence report. Neither PCORI nor AHRQ directly participated in literature searches; study eligibility criteria determination; data analysis or interpretation; or preparation, review, or manuscript approval for publication.

RESULTS

Characteristics of Reviewed Studies

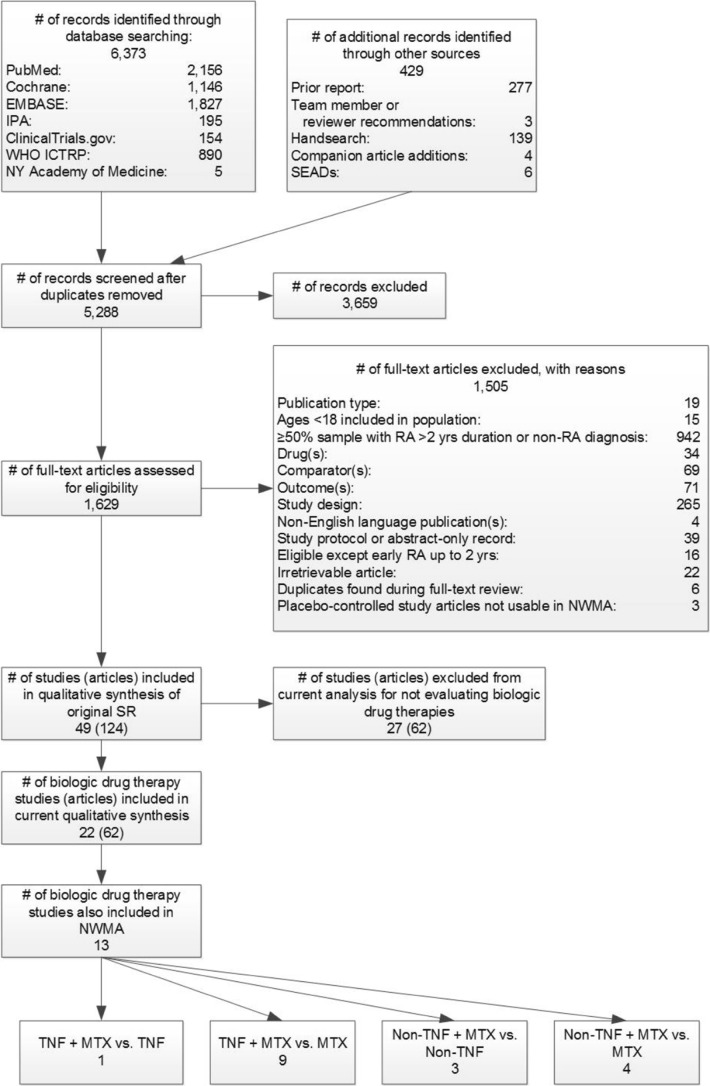

We identified 6373 citations from electronic searches and 429 from other sources (Fig. 3). We were unable to use pairwise meta-analyses due to a lack of head-to-head studies. In this paper, we report results from trials of biologic comparisons only. For these comparisons, we found 22 RCTs with low or medium risk of bias (Table 2). We included 13 studies in our NWMA.

Figure 3.

Summary of literature search flow and yield for early rheumatoid arthritis. IPA, International Pharmaceutical Abstracts; MTX, methotrexate; NWMA, network meta-analysis; NY, New York; RA, rheumatoid arthritis; SEADs, supplemental evidence and data; TNF, tumor necrosis factor; vs., versus; WHO ICTRP, World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform; yrs, years.

Table 2.

Characteristics of Included Trials

| Characteristics | |

|---|---|

| Studies (articles) | 22 (61) |

| Patients | 9,934 |

| Range of % female | 53 to 81 |

| Age: range of means | 46 to 57 |

| Risk of bias (N studies)* |

Low: 4 Medium: 17 High: 7 |

| Study duration | 1 to 2 years |

| N studies reporting on benefits (articles) | 22 (61) |

| N studies reporting on harms (articles) | 22 (59) |

| N studies reporting on subgroup effects (articles) | 4 (17) |

N number

*Some studies received more than one risk of bias rating because we assigned different ratings to specific outcomes reported by the same study. For this reason, the N’s of studies with different ratings will not add up to the total of 22 studies included in this paper.

Study durations ranged from 6 months to 2 years. Over half of the study populations were women (range 53 to 81%) with mean ages ranging from 46 to 57 years. Included studies almost exclusively enrolled patients with high disease activity at baseline as measured by mean or median Disease Activity Score (DAS) 28 scores (range of mean scores 3.6 to 7.1). Among studies reporting MTX use, 18 studies (82%) enrolled MTX-naïve patient samples; the remaining 3 studies enrolled patients with prior csDMARD use (including MTX). Most trials used ACR response, disease activity scores to measure clinical improvement, and Sharp or Sharp/van der Heijde scores to measure radiographic progression of the disease. Trials examining function or quality of life most commonly used the Health Assessment Questionnaire (HAQ) or Medical Outcomes Study Short Form 36 (SF-36). Harms studies generally described overall withdrawals, withdrawals due to adverse events, and specific adverse events including the most commonly occurring across all eligible drugs according to their FDA-approved labels. The majority (N = 21, 95%) were at least partially industry funded. Table 3 summarizes main findings and the strength of evidence. The remainder of results are organized such that we present evidence on the combination of biologics with MTX compared first to biologic monotherapy and second to MTX monotherapy for both TNF and non-TNF biologics. NWMA, when available, follows the comparisons.

Table 3.

Summary of Findings About Benefits and Harms of Treatments for Early Rheumatoid Arthritis with Strength of Evidence Grades

| Key comparisons | Efficacy Strength of evidence |

Harms Strength of evidence |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment types | Specific treatments | Rating | Explanation | Rating | Explanation |

| TNF biologics vs. MTX | ADA + MTX vs. ADA vs. MTX | Moderate | ACR response and remission significantly higher, radiographic progression less, and functional capacity significantly improved with ADA + MTX vs. ADA or with ADA vs. MTX.17 | Moderate | No significant differences in discontinuation because of adverse events or serious adverse events for ADA + MTX vs. ADA or for ADA vs. MTX17 |

| Non-TNF biologics vs. MTX | ABA + MTX vs. ABA vs. MTX | Low | No significant differences in ACR response50, 53 or remission50 for ABA + MTX vs. ABA or for ABA vs. MTX | Low | No significant differences in discontinuation because of adverse events or serious adverse events for ABA + MTX vs. ABA or for ABA vs. MTX50 |

| TCZ + MTX vs. TCZ or TCZ vs. MTX | Low | Remission significantly higher for TCZ + MTX vs. TCZ and TCZ vs. MTX51, 52 | Moderate | No significant differences in discontinuation because of adverse effects or serious adverse events for TCZ + MTX vs. TCZ or for TCZ vs. MTX51, 52 | |

| Insufficient | Functional capacity and disease activity51, 52 | ||||

| ADA + MTX vs. MTX | Moderate | Functional capacity significantly improved for ADA + MTX vs. MTX17, 22, 24, 26, 33, 62 | Low | No significant differences in discontinuation because of adverse events for ADA + MTX vs. MTX17, 22, 24, 26, 33, 62 | |

| Low | ACR response significantly higher with ADA + MTX vs. MTX17, 22, 24, 26, 33, 62 | Low | No significant differences in serious adverse events for ADA + MTX vs. MTX17, 22, 24, 26, 33, 62 | ||

| Low | Remission significantly higher with ADA + MTX vs. MTX17, 22, 24, 26, 33, 62 | ||||

| Low | Radiographic progression less with ADA + MTX vs. MTX17 | ||||

| TNF biologic + MTX vs. MTX monotherapy | CZP + MTX vs. MTX | Low | ACR response36, 63 significantly higher and radiographic progression20 less for CZP + MTX vs. MTX | Low | No significant differences in discontinuation because of adverse effects or serious adverse events20 |

| Low | Remission significantly higher and functional capacity improved for CZP + MTX vs. MTX20 | ||||

| ETN + MTX or ETN vs. MTX | Moderate | ACR response significantly higher and radiographic progression less for ETN + MTX and ETN vs. MTX37, 38 | Low | No significant differences in discontinuation because of adverse effects or serious adverse events37, 38 | |

| Low | Remission rates significantly higher for ETN + MTX and ETN vs. MTX37, 38 | ||||

| Low | Functional capacity mixed for ETN + MTX and ETN vs. MTX37, 38 | ||||

| IFX + MTX vs. MTX | Low | Remission rates45, 46 significantly higher and functional capacity45, 46 greater for IFX + MTX vs. MTX | Low | No significant differences in discontinuation because of adverse effects or serious adverse events45 | |

| Insufficient | Disease activity45–47 and radiographic progression45, 46 for IFX + MTX vs. MTX | ||||

| TNF biologic vs. csDMARD combination therapy (e.g., triple therapy) | IFX + MTX vs. MTX + SSZ + HCQ | Low | ACR response significantly higher for IFX + MTX vs. MTX + SSZ+ HCQ64 | Low | No significant differences in discontinuation because of adverse effects or serious adverse events.64 |

| IFX + MTX + SSZ + HCQ+ PRED vs. MTX + SSZ + HCQ + PRED | Low | No significant differences in ACR response, radiographic progression, or remission for IFX + MTX + SSZ + HCQ + PRED vs. MTX + SSZ + HCQ + PRED65 | Low | No significant differences in discontinuation because of adverse effects or serious adverse events65 | |

| Low | No significant differences in functional capacity for IFX + MTX + SSZ + HCQ + PRED vs. MTX + SSZ + HCQ + PRED65 | ||||

| Non-TNF biologic vs. MTX monotherapy | ABA + MTX vs. MTX | Moderate | Disease activity significantly improved and remission rates higher for ABA + MTX vs. MTX50, 53 | Low | No significant differences in discontinuation because of adverse effects or serious adverse events53 |

| Low | Radiographic progression significantly less for ABA + MTX vs. MTX53 | ||||

| Low | Functional capacity mixed for ABA + MTX vs. MTX50, 53 | ||||

| RIT + MTX vs. MTX | Moderate | Disease activity significantly improved and radiographic progression less for RIT + MTX vs. MTX57 | Moderate | No significant differences in discontinuation because of adverse effects or serious adverse events57 | |

| Moderate | Remission rates significantly higher for RIT + MTX vs. MTX57 | ||||

| Moderate | Functional capacity significantly improved for RIT + MTX vs. MTX57 | ||||

| TCZ + MTX vs. MTX | Moderate | Radiographic progression less for TCZ + MTX vs. MTX51, 52 | Moderate | No significant differences in discontinuation because of adverse effects or serious adverse events51, 52 | |

| Low | Remission significantly higher for TCZ + MTX vs. MTX51, 52 | ||||

| Insufficient | Disease activity and functional capacity for TCZ + MTX vs. MTX51, 52 | ||||

| TNF vs. non-TNF biologics | RIT vs. ADA or ETN | Low | Functional capacity significantly improved for RIT vs. ADA or ETN66 | Insufficient | Discontinuation because of adverse effects or serious adverse events66 |

| Insufficient | Disease activity or remission for RIT vs. ADA or ETN66 | ||||

ABA abatacept, ACR American College of Rheumatology, ADA adalimumab, csDMARD conventional synthetic DMARD, CZP certolizumab pegol, DAS Disease Activity Score, DMARD disease-modifying antirheumatic drug, ETN etanercept, HCQ hydroxychloroquine, IFX infliximab, MTX methotrexate, PRED prednisone, RIT rituximab, TCZ tocilizumab, TNF tumor necrosis factor, tsDMARD targeted synthetic DMARD, vs. versus

TNF Biologics

TNF Biologic Plus Methotrexate Versus TNF Biologic Monotherapy

One RCT of adalimumab (ADA) provided evidence for direct comparison of a TNF biologic plus MTX with TNF biologic monotherapy.17 The NWMA provided some information for ETN as noted below. No comparisons were available for certolizumab pegol (CZP), golimumab (GOL), or infliximab (IFX).

Adalimumab

The PREMIER study17 (N = 799) compared ADA (40 mg biweekly) plus MTX (20 mg/week) with ADA monotherapy (or MTX monotherapy further described below) in MTX-naïve patients with early aggressive RA.17 ADA plus MTX had significantly higher ACR50 response (59% vs. 37%, respectively, p < 0.001), smaller radiographic changes (modified Sharp/van der Heijde score [mTSS], 1.9 vs. 5.5, respectively; p < 0.001), and higher remission rates (DAS28 < 2.6; 49% vs. 25%, respectively, p < 0.001) than ADA monotherapy at 2 years. Additionally, the combination therapy group achieved greater improvement in functional capacity than the ADA monotherapy group (HAQ-DI mean change, − 1.1 vs. − 0.8, respectively; p = 0.0002). During the 10-year open-label extension,18 patients taking ADA plus MTX had significantly less radiographic progression than those on ADA monotherapy, but results were limited by a 34% attrition rate.

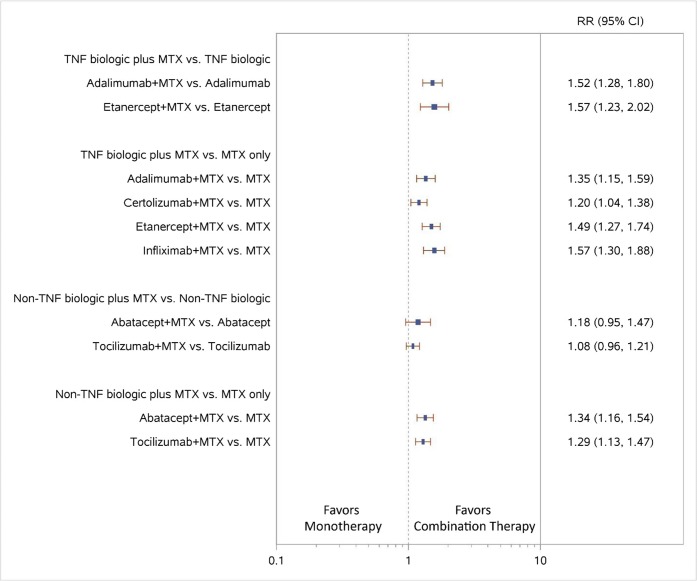

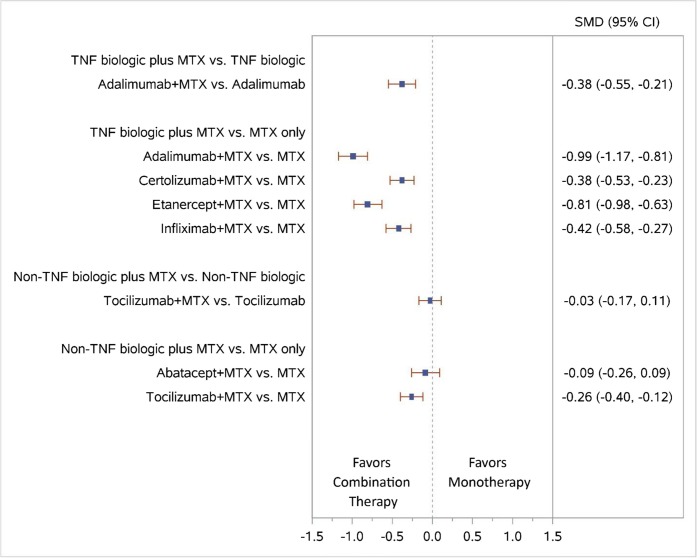

Results of the NWMA also favored the combination of ADA plus MTX versus ADA monotherapy for higher ACR50 response (relative risk [RR], 1.52; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.28 to 1.80) (Fig. 4) and less radiographic progression (standardized mean difference [SMD], − 0.38; 95% CI, − 0.55 to − 0.21) (Fig. 5).

Figure 4.

Forest plot for network meta-analysis (low SOE grades for all NWMA effect estimates) of biologic plus MTX vs. biologic or MTX only: ACR50 response rates. 95% CI, 95% confidence interval; MTX, methotrexate; RR, relative risk; TNF, tumor necrosis factor; vs., versus.

Figure 5.

Forest plot for network meta-analysis (low SOE grades for all NWMA effect estimates) of biologic plus MTX vs. biologic MTX only: change from baseline in radiographic joint damage score. 95% CI, 95% confidence interval; MTX, methotrexate; SMD, standardized mean difference (mean difference divided by standard deviation); TNF, tumor necrosis factor; vs., versus.

Etanercept (ETN)

No study examined ETN plus MTX compared with ETN monotherapy directly; NWMA favored the combination of ETN plus MTX over ETN monotherapy for higher ACR50 response (RR, 1.57; 95% CI, 1.23 to 2.02) (Fig. 4). NWMA examining ETN plus MTX versus ETN monotherapy found no significant differences in all discontinuations or discontinuations due to adverse events (data not shown).

TNF Biologic Plus Methotrexate Versus Methotrexate Monotherapy

Thirteen RCTs compared a TNF biologic plus MTX with MTX monotherapy. Overall, the TNF biologics plus MTX had smaller radiographic changes and higher remission rates than MTX monotherapy. NWMA found lower overall discontinuation rates for combination therapy consisting of TNF biologics (specifically, ADA, CZP, and ETN, but not IFX) plus MTX than MTX monotherapy (range of RR, 0.64 [95% CI, 0.53 to 0.78] to 0.66 [95% CI, 0.43 to 1.00]) (data not shown). However, neither serious adverse events nor discontinuations because of adverse events differed between the groups.

Adalimumab

Five RCTs examined the combination of ADA (40 mg biweekly) plus MTX (ranging from 8 to 20 mg/week) with MTX monotherapy over 26 weeks to 2 years.17–35 Results were consistent: four trials showed improvements in disease activity and functional improvement, and five trials showed smaller radiographic changes for the combination of ADA plus MTX; two trials showed no significant differences but trended in favor of combination therapy. The trials showing differences were conducted over a shorter period (26 weeks). NWMA found higher ACR50 responses and less radiographic progression for ADA plus MTX combination therapy than for MTX monotherapy (RR, 1.35; 95% CI, 1.15 to 1.59, and SMD, − 0.99; 95% CI, − 1.17 to − 0.81, respectively) (Figs. 4 and 5).

Certolizumab Pegol

Two RCTs examined the combination of CZP plus MTX versus MTX monotherapy in MTX-naïve patients.20, 36 One 24-week Japanese trial20 and one 52-week multinational trial36 randomized patients with early RA and poor prognostic factors (high anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide antibody, positive RF, or bony erosions) to CZP plus MTX or to MTX monotherapy. Both trials reported significantly higher DAS28-ESR remission rates (score < 2.636 or not defined20) and functional capacity and significantly lower radiographic progression among patients receiving combination therapy than among patients receiving MTX monotherapy.

In the NWMA, higher ACR50 response rates and less radiographic progression were noted for CZP plus MTX combination therapy than MTX monotherapy (RR, 1.20; 95% CI, 1.04 to 1.38, and SMD, − 0.38; 95% CI, − 0.53 to − 0.23, respectively) (Figs. 4 and 5).

Etanercept

Three trials compared ETN plus MTX with MTX monotherapy.37–39 The first trial included 542 patients with early RA followed over 2 years.37, 40–44 Patients in the ETN plus MTX group had a significantly higher ACR50 response (70.7% vs. 49.0%, p < 0.001) and greater improvement in functional capacity (HAQ mean change − 1.02 vs. − 0.72, p < 0.0001) than MTX monotherapy at 52 weeks. Remission was also significantly higher in the ETN plus MTX group (DAS44 remission < 1.6; 51.3% vs. 27.8%, p < 0.0001). The second trial found no significant difference in ACR20 response rates, radiographic changes, or physical function at 12 months.36 The third trial39 did not find any significant differences in DAS28 between groups but was of shorter duration (24 weeks) and smaller sample size (n = 26).

In the NWMA, higher ACR50 response rates and less radiographic progression were also noted for ETN plus MTX combination therapy than MTX monotherapy (RR, 1.49; 95% CI, 1.27 to 1.74, and SMD, − 0.81; 95% CI, − 0.98 to − 0.63, respectively) (Figs. 4 and 5).

Infliximab

Three trials examined the combination of IFX plus MTX compared with MTX monotherapy in MTX-naïve patients.45–47 The largest trial (n = 1049) compared the efficacy of initiating two different combinations of IFX (3 mg/kg or 6 mg/kg) plus MTX (20 mg/week) with MTX monotherapy over 54 weeks45, 48, 49 and found improved ACR response rates and HAQ scores for both IFX plus MTX combination therapy groups compared with MTX monotherapy (ACR50: 45.6% vs. 50.4% vs. 31.1%, p < 0.001, respectively; patients with HAQ increase ≥ 0.22 units from baseline: 76.0%, 75.5%, 65.2%, p < 0.004, respectively). Patients treated with IFX plus MTX also had higher rates of remission (DAS28-ESR < 2.6: 21.3% for IFX combination therapy groups vs. 12.3% for MTX only, p < 0.001)49 and less radiographic progression (modified SHS change 0.4 to 0.5 for IFX combination therapy groups vs. 3.7 for MTX only, p < 0.001).45 The smaller trials found improved46 or trending47 ACR50 responses in favor of IFX combination therapy at 54 weeks among patients receiving IFX plus MTX combination therapy.

In the NWMA, IFX plus MTX combination therapy led to higher ACR50 response rates and less radiographic progression than MTX monotherapy (RR, 1.57; 95% CI, 1.30 to 1.88, and SMD, − 0.42; 95% CI, − 0.58 to − 0.27, respectively) (Figs. 4 and 5).

Non-TNF Biologics

Non-TNF Biologic Plus Methotrexate Versus Non-TNF Biologic Monotherapy

Abatacept (ABA)

One RCT, the multinational AVERT trial (n = 351), compared the combination of ABA (125 mg/week) plus MTX (7.5 mg/week) with ABA monotherapy.50 This double-blind RCT compared treatments over 1 year; at year 2, patients with DAS28-CRP < 3.2 were tapered off treatment. If patients experienced an RA flare by month 15, they were given ABA plus MTX. No significant differences were noted for ABA plus MTX versus ABA monotherapy for ACR50 response, remission (DAS28-CRP < 2.6), or functional capacity.

Tocilizumab (TCZ)

Two RCTs assessed differences in efficacy between a TCZ plus MTX combination and TCZ monotherapy in MTX-naïve populations.51, 52 The FUNCTION tria151 examined TCZ plus MTX combination therapy over 1 year in 1162 patients with early aggressive RA (moderate to severe active RA classified by ACR criteria). After 1 year, 49% in the TCZ (8 mg/kg/month) plus MTX (10–30 mg/week) combination, and 39.4% in the TCZ monotherapy group achieved remission (DAS28-ESR < 2.6) (p < 0.001). The U-Act-Early trial52 examined 317 patients with early RA over 2 years. Patients were randomized to TCZ (8 mg/kg/month) plus MTX (10–30 mg/week), or TCZ monotherapy. At 2 years, there were no differences in remission for TCZ plus MTX versus TCZ monotherapy (DAS28 < 2.6); 86% vs. 88%). Both trials reported less radiographic progression with TCZ plus MTX than with MTX monotherapy.

Non-TNF Biologic Plus Methotrexate Versus Methotrexate Monotherapy

Abatacept

The AGREE trial was a multinational trial of 509 early RA patients (98% MTX naïve) with poor prognostic factors comparing ABA plus MTX with MTX monotherapy over 2 years.53–56 After 1 year, the ABA plus MTX group had significantly higher ACR50 response and greater functional benefit than the MTX monotherapy group (ACR50: 57.4% vs. 42.3%, respectively, p < 0.001; HAQ-DI % change of > 0.3 units: 71.9% vs. 62.1%, respectively, p = 0.024). The ABA plus MTX group also had significantly higher remission rates (DAS28-CRP < 2.6: 41.4% vs. 23.3%, p < 0.001) and less mean radiographic changes (Genant-modified Sharp score: 0.63 vs. 1.06, p = 0.040) than the MTX monotherapy group. Less radiographic progression was noted at 2 years for the ABA plus MTX group compared with the MTX monotherapy group.55

The multinational AVERT study (n = 351) compared the combination of ABA plus MTX with MTX monotherapy.50 At 1-year, patients in the ABA plus MTX group had significantly higher remission rates than the MTX monotherapy comparison group (DAS28-CRP < 2.6: 60.9% vs. 45.2%, respectively, p = 0.010). Remission rates remained higher for ABA plus MTX than for the MTX monotherapy group following treatment withdrawal at 18 months (DAS28-CRP < 2.6: 14.8% vs. 7.8%, respectively, p = 0.045). Overall, ABA plus MTX had smaller radiographic changes and higher remission rates than MTX monotherapy.

The NWMA found significant differences in ACR50 response when comparing ABA plus MTX with MTX monotherapy (RR, 1.34; 95% CI, 1.16 to 1.54), consistent with results from the AGREE and AVERT trials (Fig. 4). The combination of ABA plus MTX had numerically less radiographic progression than MTX monotherapy, but the difference was not significant (SMD, − 0.09; 95% CI, − 0.26 to 0.09) (Fig. 5).

In NWMA, there was no difference in overall discontinuation between ABA plus MTX and MTX alone, though ABA plus MTX had fewer discontinuations due to adverse events (RR, 0.49, 95% CI, 0.28 to 0.86) (data not shown).

Rituximab

One trial57–59 (n = 755) randomized MTX-naïve patients to rituximab (RIT) (1 g days 1 and 15) plus MTX (7.5–20 mg/week), RIT (500 mg days 1 and 15) plus MTX, or MTX monotherapy over 52 weeks. Both RIT plus MTX groups had significantly improved disease activity (DAS28: 43%, 40%, 20%, respectively, p < 0.001) and remission rates (DAS28-ESR < 2.6: 31%, 25%, 13%, respectively, p < 0.0010) and less radiographic change (0.36, 0.65, 1.08, respectively, p < 0.001) compared with MTX monotherapy. Overall, RIT plus MTX had smaller radiographic changes and higher remission rates than MTX monotherapy. Functional capacity (measured by HAQ-DI decrease > 0.22) improved more in both of the RIT plus MTX groups than in the MTX monotherapy group (HAQ response, 88% and 87% vs. 77%; p < 0.05). Discontinuation because of adverse events and serious adverse events did not differ across groups.

Tocilizumab

Two RCTs, the FUNCTION trial51 (N = 1162) and the U-Act-Early trial52 (N = 317), both previously described in the “Non-TNF Biologic Plus Methotrexate Versus Non-TNF Biologic Monotherapy” section, assessed differences in efficacy between TCZ plus MTX and MTX monotherapy in MTX-naïve populations. In both trials, TCZ plus MTX combination therapy led to smaller radiographic changes and higher remission rates (DAS28-ESR < 2.6: 49% vs. 19.5%, p < 0.001) than MTX monotherapy after 1 to 2 years. Both trials demonstrated greater functional capacity in the combination group than the MTX monotherapy group. Overall discontinuation rates, discontinuation because of adverse events, and serious adverse events did not differ across groups.

Subgroups

Only three RCTs compared drug therapies among different subgroups defined by demographics, disease activity, or coexisting conditions.33, 38, 45 We could not draw any conclusions about response rates or serious adverse events between older and younger patients or between people with different levels of disease activity.

DISCUSSION

Although several biologic agents are available, head-to-head evidence remains limited. Combination therapy with TNF or non-TNF biologics plus MTX resulted in improved disease control, DAS-defined remission, and functional capacity compared with monotherapy of either MTX or a biologic. Network meta-analyses (NWMAs) found higher ACR50 response for combination therapy of biologic plus MTX than MTX monotherapy. The results of comparative NWMA for overall discontinuation and discontinuation attributed to adverse events had confidence intervals too wide to support firm conclusions. Subgroup data were limited.

Eligible early RA studies almost exclusively included patients with high disease activity. In contrast, patients with early RA may present in a clinical setting with varying levels of severity. Patients with early RA enrolled in trials consist of highly selected individuals.60 Although the evidence for the effectiveness of biologics plus MTX in early RA is favorable, it is not the standard of care for several reasons. First, some data indicate that certain patients will do well on MTX monotherapy, but no information is available about how to identify or predict who these patients will be.33, 38, 45 Second, many insurers require MTX failure as a prerequisite to add a biologic. Third, some patients may be wary of a combination therapy approach in early disease (e.g., cost, side effects, injections).

Several limitations of our review should be considered. No consensus exists on defining early RA. For this review, we defined populations with early RA as having a diagnosed disease duration of 1 year or less and included mixed population studies if > 50% of the study populations had an early RA diagnosis. Patients described in this way may have had longer symptoms. Although existing evidence of biologics in combination with MTX shows that this regimen can improve disease activity, we do not know whether starting biologic treatment rather than MTX improves long-term prognosis. Because of a lack of head-to-head trials, we often relied on NWMA to estimate the comparative effectiveness of interventions of interest for treating patients with early RA. NWMAs are an important analytic tool in the absence of direct head-to-head evidence, but also have limitations; thus, we graded them as low strength of evidence. NWMAs often yield estimates with wide confidence intervals that encompass clinically relevant benefits or harms for both drugs (or combination therapies) being compared. The network geometry was mostly star-shaped with very few closed loops, which limited the number of tests we could use to assess transitivity and consistency. The FDA has approved several biosimilars, but there were no eligible studies of biosimilars.

Future research directions include comparisons of patients with different degrees of disease activity or poor prognostic factors and longer-term effects. Data are needed for examination of biosimilars. Studies with longer treatment periods and follow-up of 5 years or longer would provide better information on long-term effectiveness, adherence, and adverse events. They would also yield insights as to whether starting with a biologic improves long-term prognosis of RA.

Analyses of subpopulations based on age and coexisting medical conditions would also be helpful for clinicians and patients newly diagnosed with RA. Currently, treatment selection based on benefits and harms is difficult in these populations. Additionally, patient-centered research is needed with appropriate use of patient-reported outcomes and other patient-generated health data so that results are truly reflective of patient preferences and desires.

In conclusion, for patients with early RA and almost exclusively high disease activity, qualitative data and NWMAs suggest that the combination of a TNF or non-TNF biologic with MTX improves disease activity and DAS-defined remission when compared with either biologic or MTX monotherapy.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Laurie Leadbetter, M.S.L.S., and Christiane Voisin, M.S.L.S., who provided library services; Loraine Monroe for editorial assistance; Charli Randolph, B.A., who assisted with data abstraction, data accuracy checking, and full-text article retrieval; Claire Baker, who assisted with data accuracy checking and full-text article retrieval; Cassandra J. Barnhart, M.P.H., who assisted with full-text article retrieval; Ursula Griebler, Ph.D., M.P.H., who helped assign risk of bias ratings to our included studies; Christina Kien, M.A., who helped assign risk of bias ratings to our included studies; Gernot Wagner, M.D., who provided instruction to Mr. Coker-Schwimmer on using data visualization software to read figure-only study data and reviewed data retrieved this way; and Carol Woodell, B.S.P.H., for project management.

Financial Support

This project was funded under contract HHSA290201500011I_HHSA29032010T from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), US Department of Health and Human Services, Rockville, MD (AHRQ Publication No. 18-EHC015-EF).

The Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) funded the report (PCORI Publication No. 2018-SR-02). The findings and conclusions in this document are those of the authors, who are responsible for its contents; the findings and conclusions do not necessarily represent the views of AHRQ or PCORI. Therefore, no statement in this report should be construed as an official position of PCORI, AHRQ, or of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Footnotes

The original version of this article was revised due to a retrospective Open Access order

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Change history

5/26/2020

This article has been amended to include open access.

References

- 1.Wasserman AM. Diagnosis and management of rheumatoid arthritis. Am Fam Physician. 2011;84(11):1245–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smolen JS, Collaud Basset S, Boers M, Breedveld F, Edwards CJ, Kvien TK, et al. Clinical trials of new drugs for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis: focus on early disease. Ann Rheum Dis. 2016;75(7):1268–71. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-209429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Singh JA, Saag KG, Bridges SL, Jr., Akl EA, Bannuru RR, Sullivan MC, et al. 2015 American College of Rheumatology guideline for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care Res 2016;68(1):1–25. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Smolen JS, Landewe R, Bijlsma J, Burmester G, Chatzidionysiou K, Dougados M, et al. EULAR recommendations for the management of rheumatoid arthritis with synthetic and biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs: 2016 update. Ann Rheum Dis 2017. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.van Vollenhoven RF, Nagy G, Tak PP. Early start and stop of biologics: has the time come? BMC Med. 2014;12:25. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-12-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goekoop-Ruiterman YP, de Vries-Bouwstra JK, Allaart CF, van Zeben D, Kerstens PJ, Hazes JM, et al. Clinical and radiographic outcomes of four different treatment strategies in patients with early rheumatoid arthritis (the BeSt study): a randomized, controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52(11):3381–90. doi: 10.1002/art.21405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Donahue KE, Jonas DE, Hansen RA, Roubey R, Jonas B, Lux LJ, et al. Drug Therapy for Rheumatoid Arthritis in Adults: an Update [Internet] MD: Rockville; 2012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Donahue KE, Gartlehner G, Schulman ER, Jonas B, Coker-Schwimmer E, Patel SV, et al. Drug therapy for early rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review update. In: Quality AfHRa, ed. Rockville, MD: Comparative Effectiveness Review No. 211. (Prepared by the RTI International-University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Evidence-based Practice Center under Contract No. 290–2015-00011-I for AHRQ and PCORI.); 2018. [PubMed]

- 9.Wallace BC, Small K, Brodley CE, Lau J, Trikalinos TA. Proceedings of the 2nd ACM SIGHIT International Health Informatics Symposium. Miami: ACM; 2012. Deploying an interactive machine learning system in an evidence-based practice center: abstrackr; pp. 819–24. [Google Scholar]

- 10.U.S. Food and Drug Administration.CFR - Code of Federal Regulations Title 21. Silver Spring, MD; 2017. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cdrh/cfdocs/cfcfr/CFRSearch.cfm?fr=312.32. Last updated on August 14, 2017. Accessed 7 Sep 2017

- 11.Higgins JP, Green S, eds. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions: the Cochrane Collaboration; 2011.

- 12.Sterne JA, Hernan MA, Reeves BC, Savovic J, Berkman ND, Viswanathan M, et al. ROBINS-I: a tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. BMJ. 2016;355:i4919. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i4919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.White IR, Barrett JK, Jackson D, Higgins JP. Consistency and inconsistency in network meta-analysis: model estimation using multivariate meta-regression. Res Synth Methods. 2012;3(2):111–25. doi: 10.1002/jrsm.1045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.White IR. Network meta-analysis. Stata J. 2015;15(4):951–85. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shim S, Yoon BH, Shin IS, Bae JM. Network meta-analysis: application and practice using Stata. Epidemiol Health. 2017;39:e2017047. doi: 10.4178/epih.e2017047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Berkman ND, Lohr KN, Ansari MT, Balk EM, Kane R, McDonagh M, et al. Grading the strength of a body of evidence when assessing health care interventions: an EPC update. J Clin Epidemiol. 2014;68(11):1312–24. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2014.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Breedveld FC, Weisman MH, Kavanaugh AF, Cohen SB, Pavelka K, van Vollenhoven R, et al. The PREMIER study: a multicenter, randomized, double-blind clinical trial of combination therapy with adalimumab plus methotrexate versus methotrexate alone or adalimumab alone in patients with early, aggressive rheumatoid arthritis who had not had previous methotrexate treatment. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54(1):26–37. doi: 10.1002/art.21519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Keystone EC, Breedveld FC, van der Heijde D, Landewe R, Florentinus S, Arulmani U, et al. Longterm effect of delaying combination therapy with tumor necrosis factor inhibitor in patients with aggressive early rheumatoid arthritis: 10-year efficacy and safety of adalimumab from the randomized controlled PREMIER trial with open-label extension. J Rheumatol. 2014;41(1):5–14. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.130543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ammitzboll CG, Thiel S, Jensenius JC, Ellingsen T, Horslev-Petersen K, Hetland ML, et al. M-ficolin levels reflect disease activity and predict remission in early rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2013;65(12):3045–50. doi: 10.1002/art.38179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Atsumi T, Yamamoto K, Takeuchi T, Yamanaka H, Ishiguro N, Tanaka Y, et al. The first double-blind, randomised, parallel-group certolizumab pegol study in methotrexate-naive early rheumatoid arthritis patients with poor prognostic factors, C-OPERA, shows inhibition of radiographic progression. Ann Rheum Dis. 2016;75(1):75–83. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2015-207511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Axelsen MB, Eshed I, Horslev-Petersen K, Stengaard-Pedersen K, Hetland ML, Moller J, et al. A treat-to-target strategy with methotrexate and intra-articular triamcinolone with or without adalimumab effectively reduces MRI synovitis, osteitis and tenosynovitis and halts structural damage progression in early rheumatoid arthritis: results from the OPERA randomised controlled trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 2015;74(5):867–75. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Detert J, Bastian H, Listing J, Weiss A, Wassenberg S, Liebhaber A, et al. Induction therapy with adalimumab plus methotrexate for 24 weeks followed by methotrexate monotherapy up to week 48 versus methotrexate therapy alone for DMARD-naive patients with early rheumatoid arthritis: HIT HARD, an investigator-initiated study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2013;72(6):844–50. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-201612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Emery P, Smolen JS, Ganguli A, Meerwein S, Bao Y, Kupper H, et al. Effect of adalimumab on the work-related outcomes scores in patients with early rheumatoid arthritis receiving methotrexate. Rheumatology (United Kingdom) 2016;55(8):1458–65. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kew056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Horslev-Petersen K, Hetland ML, Junker P, Podenphant J, Ellingsen T, Ahlquist P, et al. Adalimumab added to a treat-to-target strategy with methotrexate and intra-articular triamcinolone in early rheumatoid arthritis increased remission rates, function and quality of life. The OPERA Study: an investigator-initiated, randomised, double-blind, parallel-group, placebo-controlled trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73(4):654–61. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-202735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hørslev-Petersen K, Hetland ML, Ørnbjerg LM, Junker P, Pødenphant J, Ellingsen T, et al. Clinical and radiographic outcome of a treat-to-target strategy using methotrexate and intra-articular glucocorticoids with or without adalimumab induction: a 2-year investigator-initiated, double-blinded, randomised, controlled trial (OPERA) Ann Rheum Dis. 2016;75(9):1645–53. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2015-208166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kavanaugh A, Fleischmann RM, Emery P, Kupper H, Redden L, Guerette B, et al. Clinical, functional and radiographic consequences of achieving stable low disease activity and remission with adalimumab plus methotrexate or methotrexate alone in early rheumatoid arthritis: 26-week results from the randomised, controlled OPTIMA study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2013;72(1):64–71. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2011-201247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kimel M, Cifaldi M, Chen N, Revicki D. Adalimumab plus methotrexate improved SF-36 scores and reduced the effect of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) on work activity for patients with early RA. J Rheumatol; 2008:206–15. [PubMed]

- 28.Landewe R, Smolen JS, Florentinus S, Chen S, Guerette B, van der Heijde D. Existing joint erosions increase the risk of joint space narrowing independently of clinical synovitis in patients with early rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Res Ther. 2015;17:133. doi: 10.1186/s13075-015-0626-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ornbjerg LM, Ostergaard M, Jensen T, Horslev-Petersen K, Stengaard-Pedersen K, Junker P, et al. Hand bone loss in early rheumatoid arthritis during a methotrexate-based treat-to-target strategy with or without adalimumab—a substudy of the optimized treatment algorithm in early RA (OPERA) trial. Clin Rheumatol. 2017;36(4):781–9. doi: 10.1007/s10067-016-3489-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Smolen JS, Emery P, Fleischmann R, van Vollenhoven RF, Pavelka K, Durez P, et al. Adjustment of therapy in rheumatoid arthritis on the basis of achievement of stable low disease activity with adalimumab plus methotrexate or methotrexate alone: the randomised controlled OPTIMA trial. Lancet. 2014;383(9914):321–32. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61751-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Smolen JS, van der Heijde DM, Keystone EC, van Vollenhoven RF, Goldring MB, Guerette B, et al. Association of joint space narrowing with impairment of physical function and work ability in patients with early rheumatoid arthritis: protection beyond disease control by adalimumab plus methotrexate. Ann Rheum Dis. 2013;72(7):1156–62. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-201620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Strand V, Rentz AM, Cifaldi MA, Chen N, Roy S, Revicki D. Health-related quality of life outcomes of adalimumab for patients with early rheumatoid arthritis: results from a randomized multicenter study. J Rheumatol. 2012;39(1):63–72. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.101161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Takeuchi T, Yamanaka H, Ishiguro N, Miyasaka N, Mukai M, Matsubara T, et al. Adalimumab, a human anti-TNF monoclonal antibody, outcome study for the prevention of joint damage in Japanese patients with early rheumatoid arthritis: the HOPEFUL 1 study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73(3):536–43. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-202433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.van der Heijde D, Breedveld FC, Kavanaugh A, Keystone EC, Landewe R, Patra K, et al. Disease activity, physical function, and radiographic progression after longterm therapy with adalimumab plus methotrexate: 5-year results of PREMIER. J Rheumatol. 2010;37(11):2237–46. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.100208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yamanaka H, Ishiguro N, Takeuchi T, Miyasaka N, Mukai M, Matsubara T, et al. Recovery of clinical but not radiographic outcomes by the delayed addition of adalimumab to methotrexate-treated Japanese patients with early rheumatoid arthritis: 52-week results of the HOPEFUL-1 trial. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2014;53(5):904–13. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/ket465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Emery P, Bingham C O, Burmester G R, Bykerk V P, Furst D E, Mariette X, van der Heijde D, van Vollenhoven R, Arendt C, Mountian I, Purcaru O, Tatla D, VanLunen B, Weinblatt M E. Certolizumab pegol in combination with dose-optimised methotrexate in DMARD-naïve patients with early, active rheumatoid arthritis with poor prognostic factors: 1-year results from C-EARLY, a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase III study. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases. 2016;76(1):96–104. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2015-209057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Emery P, Breedveld FC, Hall S, Durez P, Chang DJ, Robertson D, et al. Comparison of methotrexate monotherapy with a combination of methotrexate and etanercept in active, early, moderate to severe rheumatoid arthritis (COMET): a randomised, double-blind, parallel treatment trial. Lancet. 2008;372(9636):375–82. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61000-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bathon JM, Martin RW, Fleischmann RM, Tesser JR, Schiff MH, Keystone EC, et al. A comparison of etanercept and methotrexate in patients with early rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med. 2000;343(22):1586–93. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200011303432201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Marcora SM, Chester KR, Mittal G, Lemmey AB, Maddison PJ. Randomized phase 2 trial of anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy for cachexia in patients with early rheumatoid arthritis. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;84(6):1463–72. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/84.6.1463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Anis A, Zhang W, Emery P, Sun H, Singh A, Freundlich B, et al. The effect of etanercept on work productivity in patients with early active rheumatoid arthritis: results from the COMET study. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2009;48(10):1283–9. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kep239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Emery P, Breedveld F, Heijde D, Ferraccioli G, Dougados M, Robertson D, et al. Two-year clinical and radiographic results with combination etanercept-methotrexate therapy versus monotherapy in early rheumatoid arthritis: a two-year, double-blind, randomized study. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62(3):674–82. doi: 10.1002/art.27268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kekow J, Moots R, Emery P, Durez P, Koenig A, Singh A, et al. Patient-reported outcomes improve with etanercept plus methotrexate in active early rheumatoid arthritis and the improvement is strongly associated with remission: the COMET trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69(1):222–5. doi: 10.1136/ard.2008.102509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dougados MR, van der Heijde DM, Brault Y, Koenig AS, Logeart IS. When to adjust therapy in patients with rheumatoid arthritis after initiation of etanercept plus methotrexate or methotrexate alone: findings from a randomized study (COMET) J Rheumatol. 2014;41(10):1922–34. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.131238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhang W, Sun H, Emery P, Sato R, Singh A, Freundlich B, et al. Does achieving clinical response prevent work stoppage or work absence among employed patients with early rheumatoid arthritis? Rheumatology (Oxford) 2012;51(2):270–4. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/ker189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.St Clair EW, van der Heijde DM, Smolen JS, Maini RN, Bathon JM, Emery P, et al. Combination of infliximab and methotrexate therapy for early rheumatoid arthritis: a randomized, controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50(11):3432–43. doi: 10.1002/art.20568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Quinn MA, Conaghan PG, O'Connor PJ, Karim Z, Greenstein A, Brown A, et al. Very early treatment with infliximab in addition to methotrexate in early, poor-prognosis rheumatoid arthritis reduces magnetic resonance imaging evidence of synovitis and damage, with sustained benefit after infliximab withdrawal: results from a twelve-month randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52(1):27–35. doi: 10.1002/art.20712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Durez Patrick, Malghem Jacques, Toukap Adrien Nzeusseu, Depresseux Geneviève, Lauwerys Bernard R., Westhovens René, Luyten Frank P., Corluy Luc, Houssiau Frédéric A., Verschueren Patrick. Treatment of early rheumatoid arthritis: A randomized magnetic resonance imaging study comparing the effects of methotrexate alone, methotrexate in combination with infliximab, and methotrexate in combination with intravenous pulse methylprednisolone. Arthritis & Rheumatism. 2007;56(12):3919–3927. doi: 10.1002/art.23055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Smolen JS, Han C, van der Heijde D, Emery P, Bathon JM, Keystone E, et al. Infliximab treatment maintains employability in patients with early rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54(3):716–22. doi: 10.1002/art.21661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Smolen JS, Han C, van der Heijde DM, Emery P, Bathon JM, Keystone E, et al. Radiographic changes in rheumatoid arthritis patients attaining different disease activity states with methotrexate monotherapy and infliximab plus methotrexate: the impacts of remission and tumour necrosis factor blockade. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68(6):823–7. doi: 10.1136/ard.2008.090019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Emery P, Burmester GR, Bykerk VP, Combe BG, Furst DE, Barre E, et al. Evaluating drug-free remission with abatacept in early rheumatoid arthritis: results from the phase 3b, multicentre, randomised, active-controlled AVERT study of 24 months, with a 12-month, double-blind treatment period. Ann Rheum Dis. 2015;74(1):19–26. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2014-206106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Burmester GR, Rigby WF, Van Vollenhoven RF, Kay J, Rubbert-Roth A, Kelman A, et al. Tocilizumab in early progressive rheumatoid arthritis: FUNCTION, a randomised controlled trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 2016;75(6):1081–91. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2015-207628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bijlsma JW, Welsing PM, Woodworth TG, Middelink LM, Petho-Schramm A, Bernasconi C, et al. Early rheumatoid arthritis treated with tocilizumab, methotrexate, or their combination (U-Act-Early): a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, double-dummy, strategy trial. Lancet. 2016;388(10042):343–55. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30363-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Westhovens R, Robles M, Ximenes AC, Nayiager S, Wollenhaupt J, Durez P, et al. Clinical efficacy and safety of abatacept in methotrexate-naive patients with early rheumatoid arthritis and poor prognostic factors. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68(12):1870–7. doi: 10.1136/ard.2008.101121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wells AF, Westhovens R, Reed DM, Fanti L, Becker JC, Covucci A, et al. Abatacept plus methotrexate provides incremental clinical benefits versus methotrexate alone in methotrexate-naive patients with early rheumatoid arthritis who achieve radiographic nonprogression. J Rheumatol. 2011;38(11):2362–8. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.110054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bathon J, Robles M, Ximenes AC, Nayiager S, Wollenhaupt J, Durez P, et al. Sustained disease remission and inhibition of radiographic progression in methotrexate-naive patients with rheumatoid arthritis and poor prognostic factors treated with abatacept: 2-year outcomes. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70(11):1949–56. doi: 10.1136/ard.2010.145268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Smolen JS, Wollenhaupt J, Gomez-Reino JJ, Grassi W, Gaillez C, Poncet C, et al. Attainment and characteristics of clinical remission according to the new ACR-EULAR criteria in abatacept-treated patients with early rheumatoid arthritis: new analyses from the Abatacept study to Gauge Remission and joint damage progression in methotrexate (MTX)-naive patients with Early Erosive rheumatoid arthritis (AGREE) Arthritis Res Ther. 2015;17:157. doi: 10.1186/s13075-015-0671-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tak PP, Rigby WF, Rubbert-Roth A, Peterfy CG, van Vollenhoven RF, Stohl W, et al. Inhibition of joint damage and improved clinical outcomes with rituximab plus methotrexate in early active rheumatoid arthritis: the IMAGE trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70(1):39–46. doi: 10.1136/ard.2010.137703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rigby W, Ferraccioli G, Greenwald M, Zazueta-Montiel B, Fleischmann R, Wassenberg S, et al. Effect of rituximab on physical function and quality of life in patients with rheumatoid arthritis previously untreated with methotrexate. Arthritis Care Res. 2011;63(5):711–20. doi: 10.1002/acr.20419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tak PP, Rigby W, Rubbert-Roth A, Peterfy C, van Vollenhoven RF, Stohl W, et al. Sustained inhibition of progressive joint damage with rituximab plus methotrexate in early active rheumatoid arthritis: 2-year results from the randomised controlled trial IMAGE. Ann Rheum Dis. 2012;71(3):351–7. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2011-200170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sokka T, Pincus T. Eligibility of patients in routine care for major clinical trials of anti-tumor necrosis factor alpha agents in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;48(2):313–8. doi: 10.1002/art.10817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Scott IC, Ibrahim F, Simpson G, Kowalczyk A, White-Alao B, Hassell A, et al. A randomised trial evaluating anakinra in early active rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2016;34(1):88–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bejarano V, Quinn M, Conaghan PG, Reece R, Keenan AM, Walker D, et al. Effect of the early use of the anti-tumor necrosis factor adalimumab on the prevention of job loss in patients with early rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum; 2008:1467–74. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 63.UCB Pharma SA. A multi-center, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study to evaluate the efficacy and safety of certolizumab pegol in combination with methotrexate in the treatment of disease modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARD)-naïve adults with early active rheumatoid arthritis. 2012 https://ClinicalTrials.gov/show/NCT01519791. Accessed on March 7, 2018.

- 64.van Vollenhoven RF, Ernestam S, Geborek P, Petersson IF, Coster L, Waltbrand E, et al. Addition of infliximab compared with addition of sulfasalazine and hydroxychloroquine to methotrexate in patients with early rheumatoid arthritis (Swefot trial): 1-year results of a randomised trial. Lancet; 2009:459–66. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 65.Leirisalo-Repo M, Kautiainen H, Laasonen L, Korpela M, Kauppi MJ, Kaipiainen-Seppanen O, et al. Infliximab for 6 months added on combination therapy in early rheumatoid arthritis: 2-year results from an investigator-initiated, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled study (the NEO-RACo Study) Ann Rheum Dis. 2013;72(6):851–7. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-201365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Porter D, van Melckebeke J, Dale J, Messow CM, McConnachie A, Walker A, et al. Tumour necrosis factor inhibition versus rituximab for patients with rheumatoid arthritis who require biological treatment (ORBIT): an open-label, randomised controlled, non-inferiority, trial. Lancet. 2016;388(10041):239–47. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00380-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]