Abstract

Research strongly suggests that family interventions can benefit patients with schizophrenia, yet current interventions often fail to consider the cultural context and spiritual practices that may make them more effective and relevant to ethnic minority populations. We have developed a family focused, culturally informed treatment for schizophrenia (CIT-S) patients and their caregivers to address this gap. Sixty-nine families were randomized to either 15 sessions of CIT-S or to a 3-session psychoeducation (PSY-ED) control condition. Forty-six families (66.7%) completed the study. The primary aim was to test whether CIT-S would outperform PSY-ED in reducing posttreatment symptom severity (controlling for baseline symptoms) on the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale. Secondary analyses were conducted to test whether treatment efficacy would be moderated by ethnicity and whether patient-therapist ethnic match would relate to efficacy and patient satisfaction with treatment. Patients included 40 Hispanic/Latinos, 14 Whites, 11 Blacks, and 4 patients who identified as “other.” In line with expectations, results from an ANCOVA indicated that patients assigned to the CIT-S condition had significantly less severe psychiatric symptoms at treatment termination than did patients assigned to the PSY-ED condition. Patient ethnicity and patient-therapist ethnic match (vs. mismatch) did not relate to treatment efficacy or satisfaction with the intervention. Results suggest that schizophrenia may respond to culturally informed psychosocial interventions. The treatment appears to work equally well for Whites and minorities alike. Follow-up research with a matched length control condition is needed. Further investigation is also needed to pinpoint specific mechanisms of change.

Keywords: schizophrenia symptoms, patient–therapist ethnic match, family therapy, culture

Schizophrenia is a disabling psychiatric disorder that occurs in roughly one out of every hundred individuals (Goldner, Hsu, Waraich, & Somers, 2002; Mueser & Jeste, 2008). It has severe consequences for patients in terms of their psychological, social, and occupational functioning (Pinkham et al., 2012; Shivashankar et al., 2013; Tsang, Leung, Chung, Bell, & Cheung, 2010) and has devastating costs to patients and family members alike (Mitsonis et al., 2012). We developed a 15-week family-focused, culturally informed therapy for schizophrenia (CIT-S) with a primary aim of decreasing the severity of patient psychiatric symptoms. The treatment also aimed to improve other aspects of patients’ quality of life and to reduce caregiver guilt, shame, and burden (Suro & Weisman de Mamani, under review); however, these topics will be addressed in separate manuscripts. The current paper focused primarily on the ability of CIT-S to reduce patient psychiatric symptoms above and beyond a three-session psychoeducation (PSY-ED)-only control condition. We also examined whether patient ethnic minority status (minority vs. majority) would moderate this effect. Discrepancies in patient and therapist ethnic background were also examined to assess whether ethnic match related to treatment efficacy and satisfaction with the treatment.

Family Treatments for Schizophrenia

Clinical trials for schizophrenia have clearly established that family interventions lead to better outcomes including reduced risk of relapse and symptom severity, as well as increased medication compliance (Dixon, Adams, & Lucksted, 2000; Dixon et al., 2010; Dyck et al., 2002; Pharoah, Mari, Rathbone, & Wong, 2004). Despite the clear efficacy of family therapy, research suggests that less than 7% of patients with schizophrenia receive any family therapy at all (Dixon, McFarlane, Hornby, & McNary, 1999). Currently, the most widely disseminated treatment for families of patients with schizophrenia is psychoeducation about the illness, which is usually delivered in brief format of one to three sessions (McFarlane, Dixon, Lukens, & Lucksted, 2003; Sota et al., 2008). Few existing interventions have taken cultural factors into account and most established interventions for schizophrenia are offered only in English. Lefley (2009) carefully reviews the literature on family psychoeducation for serious mental illness around the world in an excellent book on this topic.

A study by Barrio and Yamada (2010) offered preliminary evidence for the efficacy of a culturally based multifamily group therapy for Hispanic/Latino schizophrenia caregivers in increasing their knowledge about the illness and reducing caregiver burden. However, this group included family members only (no patients), and the impact of the group on patient psychiatric symptoms was not examined. More recently, Kopelowicz et al. (2012) adapted an existing multiple family group approach developed by McFarlane and colleagues (1995, 2002) for Spanish-speaking patients and their caregivers, with the aim of improving medication nonadherence. The treatment resulted in increased medication adherence and other improved patient outcomes. These studies aside, few treatments for schizophrenia are culturally informed and offered in languages other than English (e.g., López, Barrio, Kopelowicz, & Vega, 2012; Miranda et al., 2005; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2001). Thus, these programs may be less relevant for Spanish-speaking participants and ethnic/racial minority groups, who overwhelmingly report turning to spiritual and collectivistic values when coping with mental illness (Black, 1996; Weisman et al., 2006). In the next section, we discuss why fostering a greater sense of family collectivism and encouraging adaptive spiritual and religious beliefs and behaviors in therapy for schizophrenia may decrease patients’ psychiatric symptoms and improve other aspects of patients’ and their caregivers’ mental health.

Family Collectivism and Spirituality

A growing body of research leads us to believe that strengthening family cohesion may help decrease patient psychiatric symptoms and improve quality of life for both patients and their caregivers. For example, using cross-sectional data obtained from the Family Environment Scale, Weisman, Rosales, Kymalainen, and Armesto (2005) found that greater perceived family cohesion was associated with less severe psychiatric symptoms and lower levels of depression, anxiety, and stress in schizophrenia patients. This study further found that the benefits of cohesive family environments only extended to a subset of caregivers. Hispanic/Latino and Black caregivers who viewed their family as more cohesive also expressed lower levels of depression, anxiety, and stress. Interestingly, this association was not found for White caregivers. However, in an analog study, Weisman and López (1996) offer data suggesting that for both Whites (living in the United States) and Mexicans (living in Mexico), greater cohesion in one’s family was associated with greater likelihood of reporting favorable emotions and less likelihood of reporting unfavorable emotions toward a hypothetical sibling described to meet Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-IV (DSM-IV) criteria for schizophrenia. Thus, bolstering a sense of cohesion in the family environment may directly help reduce patients’ psychiatric symptoms and may also improve other aspects of psychological functioning for patients and caregivers alike.

Prior research also suggests that enhancing adaptive spiritual beliefs and coping techniques may help reduce patients’ psychiatric symptoms along with offering a host of other mental health benefits to patients and their loved ones. For example, Shah et al. (2011) found that greater self-reported spiritual connection was associated with lower negative symptoms. Mohr et al. (2011) found that patients with schizophrenia who reported using religion to help them adaptively cope with symptoms had fewer negative symptoms and reported a better quality of life 3 years later. Revheim, Greenberg, and Citrome (2010) found that a spiritually based group therapy for patients with schizophrenia resulted in greater perceived self-efficacy for dealing with positive symptoms and a significantly more hopeful outlook on life. Furthermore, Rosmarin, Bigda-Peyton, Öngur, Pargament, and Björgvinsson (2013) found that positive religious coping was associated with significantly greater reductions in depression, anxiety, and increases in well-being over the course of treatment (after controlling for other significant variables). Several studies (e.g., Rammohan, Rao, & Subbakrishna, 2002) have also indicated that religious caregivers benefit from their faith in coping with schizophrenia in a family member as well. For instance, Murray-Swank et al. (2006) found that after controlling for age, race, education, and gender, greater religiosity was associated with less depression, better self-esteem, and better self-care in family caregivers for people with serious mental illness. Having a sound religious belief system likely helps patients and their caregivers cope with symptoms and other aspects of the disease by offering a meaning making system (Tabak & Weisman de Mamani, 2014), a set of active and adaptive coping skills and resources (Shah et al., 2011), and various mechanisms of guidance and social support (see Weisman de Mamani, Tuchman, & Duarte, 2010, for a detailed review of this topic).

Patient Ethnicity and Patient-Therapist Ethnic Match and Satisfaction With Treatment

This study also examined, on an exploratory basis, whether ethnicity moderated treatment efficacy and whether there were differences between minorities and nonminorities on treatment satisfaction. On the one hand, the treatment may be more effective for minorities because Blacks and Hispanics/Latinos are more likely than Whites to turn to spirituality in coping with adversity (Culver, Arena, Wimberly, Antoni, & Carver, 2004; Tarakeshwar, Hansen, Kochman, & Sikkema, 2005). Additionally, as noted earlier, some research suggests that the links between greater family unity and better emotional well-being are stronger for Black and Hispanics/Latinos than for Whites (Weisman et al., 2005). Thus, the emphasis of CIT-S on family collectivism and spirituality in confronting the illness may make the treatment approach especially relevant and culturally sanctioned for minorities. On the other hand, research suggests that perceived family unity (Varela, Sanchez-Sosa, Biggs, & Luis, 2009) and spirituality (Nightingale, 2003) may benefit Whites coping with adversity as well. Because Whites may be less likely than their minority counterparts to already be engaging in spiritual practices and to turn to family for support, they may have even more to gain from a treatment intervention that incorporates these approaches. While no specific hypotheses were offered, on an exploratory basis, we examined whether ethnicity moderated treatment efficacy.

We also examined the effect of patient-therapist ethnic match on treatment efficacy and treatment satisfaction. The preponderance of data suggests that client-ethnic match has little bearing on treatment efficacy. For example, Cabral and Smith (2011) conducted a meta-analysis of 53 studies of client outcomes in mental health treatment and found no significant associations between treatment outcomes and racial/ethnic matching of clients with therapists for a range of mental disorders. Another meta-analysis conducted by a different research team (Shin et al., 2005) offered similar results. They examined both published and unpublished studies between 1991 and 2001. Using a random-effects meta-analysis model in a sample of Black and White adults seeking mental health services, they found no significant differences in functioning at treatment termination between client-patient dyads who were racially and ethnically matched versus those who were not matched. Research on this topic in schizophrenia is practically nonexistent. A PsycINFO search yielded only one abstract for an unpublished doctoral dissertation. Although we were unable to locate the full study, the abstract indicated that therapist-client ethnic match was not found to be a significant predictor of outcome as measured by the Global Assessment Scale for patients with schizophrenia (Kuipers, 1993). We explore this issue further in the current study.

Current Study

The current study focused primarily on the capacity of CIT-S to reduce patient symptom severity. Based on the research reviewed above, our primary hypothesis was that patients who received CIT-S would demonstrate decreased levels of symptom severity as compared to those who received PSY-ED. As noted earlier, we also expected the treatment to improve other aspects of patient quality of life and caregiver well-being, but these topics will be addressed in separate manuscripts. On an exploratory basis, our secondary hypotheses examined whether ethnicity moderated the impact of CIT-S on symptom severity and whether client-therapist ethnic match related to efficacy and patient satisfaction with treatment.

Method

This section begins with a detailed description of CIT-S and of our brief PSY-ED control condition.

Culturally Informed Therapy for Schizophrenia

CIT-S (see Weisman, 2005; Weisman, Duarte, Koneru, & Wasserman, 2006) is a fully manualized approach that occurs over the course of 15 weekly sessions, each lasting approximately 60–75 min and accompanied by a series of detailed handouts. This intervention incorporates therapeutic components that are informed by cross-cultural research, including novel modules on spirituality and family collectivism. It also incorporates techniques that have demonstrated efficacy in treating schizophrenia families, such as psychoeducation and communication training. Between-session homework is assigned for family members to practice the skills that are addressed during therapy. We consider CIT-S to be “culturally informed” because it accesses beliefs, behaviors, and practices from families’ cultural backgrounds that may be adaptive or, in some cases, maladaptive in coping with the illness. We attempt to modify maladaptive beliefs and behaviors throughout treatment, while adaptive ones are shaped, encouraged, and fostered. This treatment also strongly aims to foster collective beliefs and values as well as spiritual practices that research suggests are culturally sanctioned for minorities and possibly beneficial for all (Weisman & López, 1996; Weisman, 1997). We compare CIT-S against a three-session, PSY-ED control condition.

Family collectivism.

This segment was motivated by and developed based on prior research, some of which was reviewed earlier in this article. The primary aim of the family collectivism module is to help family members enhance the perspective that they are part of a team working toward unified goals. Early in treatment, participants are asked to verbalize their expectations and goals for treatment. This provides an opportunity to emphasize commonalities, as most patients and family members report that promoting the patient’s mental health and getting along better with one another are shared priorities. Handouts used to guide the module include a series of questions to generate discussion about each participant’s identification with their family unit and the way they function within this unit. Activities and homework assignments associated with this module include preparing personal narratives to describe how each family member feels they contribute to the general family functioning. Through these narratives, family members begin to consider the ways they impact the family system and to generate ideas about improving family functioning. The therapist often encourages family members to identify specific behaviors of other members that they value and believe contribute to the well-being of the family.

Therapists aim to provide a therapeutic environment where participants feel comfortable expressing any dissatisfaction with roles they have acquired or lost as a result of the patient’s schizophrenia. For example, caregivers sometimes complain that their role as a parent becomes extended when an adult child is mentally ill. Discussing these topics openly can offer important opportunities for perceptions of family unity to increase. For instance, a patient may share that he or she too feels chagrin that their caregivers are permanently stuck in a parenting role and that they are also unhappy with forever remaining in the role of a dependent child. Through this module, therapists work to unify families by emphasizing the commonalities between members and deemphasizing the differences. Emphasis is placed on how the family system works as a whole to impact family problems and the patient’s psychiatric functioning.

Psychoeducation.

This segment was primarily drawn from an intervention originally developed by Falloon, Boyd, and McGill (1984) and adapted by others (e.g., Miklowitz & Goldstein, 1997; Miklowitz, 2008; Mueser & Glynn, 1999) to address other disorders and psychiatric symptoms. Patients and family members are educated on the common symptoms of schizophrenia and are taught to identify the prodromal symptoms that may be present before a relapse. Additionally, family members are given information on the known causes of the illness and exacerbating factors, including genetics, neurochemistry, and environmental factors. Family members also learn about the impact that the family environment has on a patient’s course of illness.

Spiritual coping.

This module aims to help patients and family members access spiritual or existential beliefs that may serve as an adaptive resource in coping with the illness. Early in this module, participants are asked to provide a history of their spiritual beliefs, values, and practices. Handouts are used to guide the discussion by inquiring about participants’ beliefs in God or a supreme being, perceptions of morality, and their views on the meaning and purpose of life. Participants are asked to discuss the role of any spiritual practices that they currently use or would like to use, such as prayer, meditation, volunteerism, or religious service attendance. Spiritual practices such as forgiveness, kindness, and empathy are also discussed. Outside of treatment, family members are encouraged to engage in spiritual practices that they identify as being potentially therapeutic and then discuss these experiences in session.

Therapists make no attempt to instill or push any particular religious stance during this segment and the spirituality module is completed with all family members, regardless of whether or not they endorse a religious orientation. Family members who do not subscribe to a particular religious practice, or do not want to discuss their religious beliefs, work from a parallel set of handouts. They complete similar exercises as religious families but without specific references to “God” or “religion.” Instead, these family members engage in existential exercises such as mindfulness meditation, philosophical readings, and a discussion of spiritual concepts such as empathy and appreciation. During this module the therapist works to reframe any maladaptive uses of religion or spirituality, such as the belief that schizophrenia is a punishment from God for a previous wrongdoing. Therapists do not directly challenge any religious or spiritual beliefs held by participants. Instead, they work to guide family members into adopting more adaptive uses of religion.

Communication training.

The final two modules of CIT-S, communication training and problem solving, are also drawn largely from approaches that were developed by Falloon et al. (1984) and later modified by Miklowitz and Goldstein (1997) and others. These approaches have strong empirical support for assisting families of patients with both schizophrenia (Falloon et al., 1984) and bipolar disorder (Miklowitz & Goldstein, 1997). Communication training teaches family members a set of skills to assist them in providing support for one another more effectively. Techniques covered include active listening, expressing positive regard, and making requests for behavioral change. Skills are practiced in session through discussion and role-play. This provides the patient the opportunity to discuss with their caregivers an appropriate means to communicate their illness that may reduce stress for patients and caregivers alike.

Problem solving.

In the final phase of treatment, family members practice problem-solving skills to enhance their ability to manage the challenges associated with schizophrenia. Participants are taught to identify problems, brainstorm possible solutions without judgment, and then evaluate each idea to arrive upon the optimal solution for the chosen problem. A strategy is then put in place to carry out the solution for homework. These exercises help family members learn to view the daily challenges associated with mental illness as external problems that they can tackle as a team. This provides an opportunity for family members to work through challenges that have arisen during the course of treatment. For example, the theme of medication compliance is a concern raised by many family members about their mentally ill loved one. The problem-solving segment provides an opportunity for patients and caregivers to strategize a plan that is feasible and acceptable to all family members.

PSY-ED Comparison

Our comparison condition consists of three sessions of psychoeducation. It is identical in format to the education module of CIT-S. A three-session psychoeducation control condition was chosen in this early phase of testing CIT-S in order to address whether or not the intervention leads to clinical improvement above and beyond short-term family psychoeducation, which, although used too infrequently, has demonstrated improved patient functioning as well as benefits to caregivers (e.g., Sota et al., 2008).

Sample

Participants in this study were diagnosed with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder as confirmed by the Structured Clinical Interview for the DSM-IV, Patient Edition, (SCID-I/P, First, Spitzer, Gibbon, & Williams, 2002). To be eligible, patients were required to be in regular weekly contact (minimum of 1 hour or more per week over the past 3 months) with a caregiver willing to complete assessment batteries and engage in weekly treatment. A caregiver was defined as a biological relative, a step-relative, a spouse, or a significant other, and the relationship had to have been in existence for at least 6 months. Patients and caregivers were also required to give informed consent and agree to participate in all intervention and assessment phases of the study. To simulate real world settings, and for ethical reasons, all other types of individual psychosocial treatments were permitted.

The patient sample that was initially randomized included 69 participants (28 female, 41 male) with a mean age of 42.59 years (SD = 16.23). Of these participants, 55.1% (n = 38) were randomized to CIT-S and slightly fewer, 44.9% (n = 31), were randomized to PSY-ED. With respect to ethnicity, 58.0% (n = 40) of patients identified as Hispanic/Latino, 20.2% (n = 14) as White, 15.9% (n = 11) as Black, and 5.7% (n = 4) as “other.” Based on the pretreatment assessment, 81.2% (n = 56) of patients’ primary language was English.

Procedure

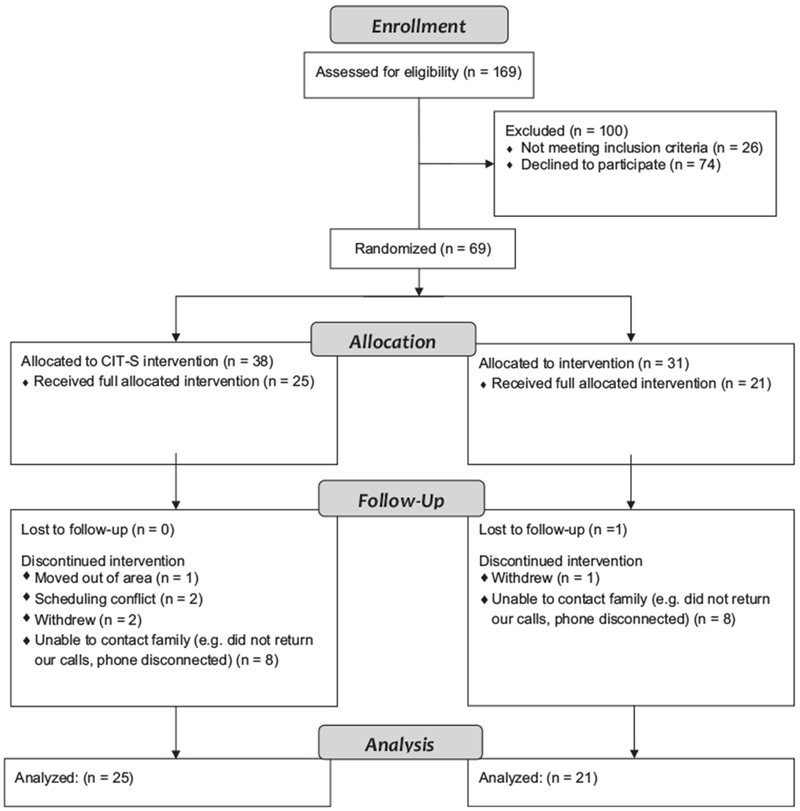

The CIT-S treatment trial is part of a larger family study on schizophrenia that examines how a culturally informed treatment and other psychosocial factors relate to functioning in patients with schizophrenia and their caregivers. Participants were screened by phone and if they appeared to meet criteria for schizophrenia, they were invited to come into the clinic for an in-person diagnostic assessment to confirm diagnosis and to assess eligibility for the treatment trial. Participants who did not have an eligible family member were filtered into a cross-sectional study on family environment or a group intervention trial. Sixty-nine participants were eligible for this study and subsequently randomized to either CIT-S or PSY-ED with one or more family members. Of those, 46 families completed the treatment. See Figure 1 for a chart outlining the flow of patients through each stage in the study.

Figure 1.

CONSORT flow diagram.

All study procedures and materials were approved by the University of Miami Institutional Review Board, and this board over-saw the research process. Participants were recruited via hospitals, community mental health centers, newspaper advertisements, and advertisements on Miami’s aboveground rail system. Participants first received a brief screening over the phone to assess eligibility. If they appeared to meet criteria, they were scheduled for a more extensive screening assessment. During this assessment, a research assistant fully explained the study process, including the randomization design. Participants were asked to review study procedures, and if they were in agreement, to sign an informed consent form. The patient was then interviewed using the SCID-I/P to confirm diagnosis. If patients met study criteria and expressed interest in the treatment arm of the study, a baseline assessment was conducted. In order to control for variability in participants’ level of reading comprehension, assessments were conducted in interview format. The baseline assessment occurred approximately 1–2 weeks before treatment. After the baseline assessment, participants were randomly assigned to either 15 weeks of CIT-S or three sessions of PSY-ED. Participants were reassessed using the same assessment battery 15–17 weeks after the first treatment session. In other words, participants in both groups received the pre and postassessments during the same time interval.

Treating clinicians on this project were all doctoral level clinical psychology students. The study’s principal investigator (Licensed Clinical Psychologist Amy Weisman de Mamani) closely monitored therapist fidelity of prescribed and proscribed behaviors and weekly supervision meetings with all treating therapists were conducted. Sixty-nine videotaped sessions from the first 23 families to enter treatment were rated as part of an earlier study (Carlson & Weisman de Mamani, 2010), using a variant of the Therapist Competency Adherence Scale (Weisman et al., 1998, 2002). The CIT-S Therapist Competency Adherence Scale includes a manual and detailed anchor points and assesses both recommended and proscribed therapist behaviors for both treatment conditions. Mean ratings across the 24 domains were 6.29 (SD = .45) on a 7-point scale (1 = poor, 7 = excellent). Overall, therapists demonstrated excellent competence and adherence on all of the 24 domains assessed, with scores ranging from adequate to excellent.

Translation of Measures

Assessments occurred in either English or Spanish depending on participant’s preference. An editorial board approach was used to translate measures from English to Spanish. This approach takes into account within group language variations and is therefore considered to be more effective than translation-back translation (Geisinger, 1994). Measures were initially translated by a native Spanish speaker of Cuban descent. An editorial board was then composed of native Spanish speakers. Members included Spanish speakers of Cuban, Nicaraguan, Costa Rican, Columbian, Mexican, and Puerto Rican descent, as well as the first author of this paper, who is a non-native Spanish speaker with personal and professional experience in Spanish-speaking countries (e.g., Mexico, Cuba, Spain) and U.S. cities where Spanish is frequently spoken (Los Angeles, Miami). Members of the board reviewed translations independently and then carefully compared measures to the original English versions. Discrepancies in the Spanish translations were then discussed to create the most language-generic version of all measures. Measures were reviewed a second time and all remaining discrepancies were discussed until there was consensus that all Spanish language measures captured the intended constructs and paralleled their English language equivalents.

Measures

Diagnosis confirmation.

To confirm schizophrenia/schizoaffective disorder diagnoses, the psychotic symptoms section of the SCID-I/P (First et al., 2002) was used. Interrater reliability of the SCID interviewers was evaluated by having all interviewers as well as the study’s principle investigator watch six videotaped interviews and independently rate each item to determine an overall diagnosis (in four of the training tapes, a diagnosis was present, and in two, it was absent). Interrater agreement using Cohen’s Kappa was 1.0. This rating indicates that there was perfect agreement in determining whether a diagnosis of schizophrenia/schizoaffective disorder was present or absent.

Symptom severity.

The Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS; Lukoff, Nuechterlein, & Ventura, 1986; Overall & Gorham, 1962) was used to measure symptom severity at baseline and following termination. The BPRS is a 24-item semistructured interview that assesses the following eight areas: unusual thought content, hallucinations, conceptual disorganization, depression, suicidality, self-neglect, bizarre behavior, and hostility. Each item is assessed using a 7-point anchor rating with 1 indicating not present to 7 indicating extremely severe. Higher scores are indicative of greater symptom severity. The first author of this study has completed a University of California, Los Angeles, BPRS training and quality assurance program and has demonstrated reliability with the scale’s creator, Dr. Joseph Ventura. Dr. Weisman de Mamani trained all graduate student interviewers. Interviewers then coded six training videotapes selected by Dr. Ventura. Intraclass correlations between interviewers and consensus ratings of Dr. Ventura ranged from .79 to .98 for total BPRS scores. A total BPRS symptom severity score can be obtained by summing across all 24 items. This was the method used for our primary analyses.

We also used the BPRS to examine three specific symptom clusters (positive, negative, and affective/mood) that emerged in a principal components analysis of the full BPRS (Ventura, Nuechterlein, Subotnik, Gutkind, & Gilbert, 2000). Cronbach’s alpha for the negative symptom cluster, which includes blunted affect, motor retardation, and emotional withdrawal was .96. Cronbach’s alpha for positive symptoms, which included unusual thought content, disorientation, hallucinations, and conceptual disorganization was .89. Cronbach’s alpha for affective (mood) symptoms, which included depression, guilt, and anxiety, was .94.

Consumer satisfaction.

After treatment termination, a 7-point Likert-type scale, ranging from 1 (very dissatisfied) to 7 (very satisfied), was given to assess how satisfied patients were with the treatment.

Statistical Analyses

All study analyses were conducted using SPSS Version 19. Prior to conducting primary analyses, the distribution of all variables was examined for normality and homoscedasticity of residuals to assess whether transformations were necessary. Additional analyses were conducted to examine the relationship of demographic variables (age, gender, language of treatment) and baseline symptom severity with our primary dependent variable, symptom severity at treatment termination. T tests and ANOVAS were used for categorical independent variables and Pearson correlation co-efficients were used for continuous ones. ANCOVA (controlling for baseline symptom severity) was used to test the primary and some of the secondary hypotheses (treatment efficacy and treatment type by ethnicity interactions). Because sample size for Blacks was small, Hispanics/Latinos and Blacks were combined for primary analyses to designate an ethnic minority subgroup. However, for exploratory hypotheses that examined ethnic matching, we also conducted analyses with ethnic groups further broken down.

Results

Preliminary Analyses

Baseline BPRS scores and pretreatment demographic variables (current age, age at illness onset, gender, ethnicity, and language preference) were compared between participants randomized to the CIT-S condition (n = 38) and those randomized to the PSY-ED condition (n = 31). The same comparisons were made between study completers and those who did not complete the study. Cases where families were randomized to treatment but later left the study before completing treatment and the termination assessment were designated as “drop-outs.” Twenty-three families (33.33%) dropped out of the study for a variety of reasons (e.g., relocation, scheduling conflicts, no longer interested in treatment, etc.). Of the study completers, 25 were in the CIT-S condition and 21 were in PSY-ED. A chi square test indicated no differences between the treatment groups on attrition, with 14 (36%) dropping out of CIT-S and 9 (30%) dropping out of PSY-ED, χ2(1) = .265, p = .80. No differences were found on baseline BPRS scores nor any demographic variable between treatment groups, nor between study completers and study drop-outs. See Table 1 for means and standard deviations.

Table 1.

Demographic Variables and Symptom Severity by Treatment Condition for All Randomized Participants and by Treatment Completers Versus Noncompleters

| CIT-S (n = 38) | PSY-ED (n = 31) | Difference statistic | Completers (n = 46) | Noncompleters (n = 23) | Difference statistic | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline BPRS | 55.24 (SD = 16.35) | 52.39 (SD = 15.76) | t(67) = .73, p = .47 | 52.39 (SD = 16.63) | 57.09 (SD = 14.63) | t(67) = 1.149, p = .25 |

| Age | 42.73 (SD = 14.31) | 42.42 (SD = 12.70) | t(66) = .08, p = .94 | 41.76 (SD = 16.74) | 44.32 (SD = 15.34) | t(66) = .61, p = .55 |

| Gender (n, % female) | 15, 39.5% | 13, 41.9% | χ2(1) = .04, p = .52 | 19, 41.3% | 9, 39.1% | χ2(1) = .01, p = .59 |

| Ethnicity (n, %) | χ2(3) = 1.55, p = .67 | χ2(3) = 3.14, p = .37 | ||||

| White | 7, 18.4% | 7, 22.5% | 11, 23.9% | 3, 13.0% | ||

| African American | 5, 13.2% | 6, 19.4% | 6, 13.0% | 5, 21.4% | ||

| Hispanic | 23, 60.5% | 17, 54.8% | 27, 58.7% | 13, 56.5% | ||

| Other | 3, 7.9 | 1, 3.2 | 2, 4.4 | 2, 9.0 | ||

| Age of illness onset | 19.36 (SD = 7.67) | 19.72 (SD = 7.91) | t(59) = −.18, p = .86 | 19.43 (SD = 8.60) | 19.60 (SD = 7.34) | T(59) = −.08, p = .94 |

| Language of treatment (n, % Spanish) | 8, 21.10% | 5, 16.1% | χ2(1) = .27, p = .42 | 9, 19.6% | 4, 17.4% | χ2(1) = .05, p = .55 |

Note. CIT-S = culturally informed treatment for schizophrenia; PSY-ED = psychoeducation; BPRS = Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale; SD = standard deviation.

All study variables had a skewness and kurtosis value within the normal range (skewness statistical value of <3 and a kurtosis statistical value of <10 as defined by Kline, 2011). Therefore, no transformations were conducted. To determine whether statistical controls were needed for covariates, we examined the relationship between the following demographic variables and symptom severity at baseline and at treatment termination: age, gender, and family member type. No relationships were found between any demographic variable and symptom severity at baseline or at treatment termination. See Table 2.

Table 2.

Relationship Between Demographic Variables and Symptom Severity

| Baseline BPRS scores | Termination BPRS scores | |

|---|---|---|

| Age | r = −.01, p = .96 | r = .19, p = .26 |

| Gender | t(44) = −1.60, p = .12 | t(44) = .090, p = .93 |

| Ethnicity (White/minority) | t(44) = 1.42, p = .16 | t(44) = .851, p = .40 |

| Age of illness onset | r = −.15, p = .34 | r = −.051, p = .76 |

| Language of treatment | t(44) = .047, p = .96 | t(44) = 1.18, p = .24 |

Note. All relationships are not significant. BPRS = Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale.

Tests of Primary Hypotheses

The following analyses include only patients who completed treatment and their termination assessment (one third of the sample was excluded because they dropped out of the study prematurely). An ANCOVA (controlling for baseline psychiatric symptoms), that included treatment type, ethnicity and the ethnicity by treatment type interaction in the model demonstrated lower posttreatment symptom severity scores for patients whose families were assigned to the CIT-S condition (M = 43.44, SD = 14.77) relative to those assigned to the PSY-ED condition (M = 53.71, SD = 17.77), F(1, 41) = 4.53, p = .039, partial η2 = .10. Thus, as hypothesized, CIT-S outperformed PSY-ED in reducing psychiatric symptoms by almost 20% with a medium effect size (Richardson, 2011). No significant main effect for ethnicity was found, F(1, 41) = .65, p = .425, and there was no treatment by ethnicity interaction, F(1, 41) = .33, p = .568.

With respect to clinical significance, it should be noted that there was an approximately 10-point difference in termination BPRS scores between CIT-S and PSY-ED completers. This is despite nearly identical scores for treatment completers in these groups at baseline (CIT-S: M = 52.08, SD = 18.04; PSY-ED: M = 52.76, SD = 15.25). Drawing from criteria presented by Leucht et al. (2005), participants in the CIT-S condition began treatment, on average, in the markedly ill range but after receiving CIT-S, improved one full category, moving them squarely into the moderately ill range. On the other hand, patients in the PSY-ED condition began and ended treatment, on average, in the markedly ill range. Thus, the implication of a 10-point difference in termination scores on the BPRS appears clinically meaningful as well.

It should be noted that when BPRS scores were broken down by positive, negative, and affective symptom cluster (controlling for baseline symptoms on that cluster), there was a pattern for mean scores to be somewhat lower on all symptom clusters. However, significant differences between CIT-S and PSY-ED groups at treatment termination only emerged when total scores were examined. In other words, no significant differences emerged for positive, F(1, 43) = 2.096, p = .155; negative, F(1, 43) = .940, p = .338; or affective, F(1,43) = .410, p = .525, symptoms.

Tests of Secondary (Exploratory) Hypotheses

A secondary aim of this study was to examine whether therapist-patient ethnic match or mismatch on minority/nonminority status had any bearing on treatment satisfaction and treatment efficacy. Six of the 10 therapists and 35 of the 46 patients were designated as minority. When patients and therapists were both either designated as a minority or both were designated as a nonminority (based on self-report) they were counted as a match. Thirty-seven of the 46 dyads fell in this group. All other dyads were counted as discrepant. An ANCOVA, controlling for baseline symptoms and treatment type, indicated that matched and unmatched groups did not differ on treatment termination BPRS scores, F(1, 42) = .28, p = .602. We reexamined this hypothesis by also counting client therapist dyads as a mismatch if they were both minorities but from different ethnic groups (e.g., a Hispanic therapist and an African American client). Using this category, 24 dyads were counted as matched and 22 were counted as discrepant. In line with the prior results, therapist-client mismatch had no relationship with BPRS termination scores, even when participant-therapist ethnicity was further broken down, F(1,42) = .67, p = .417.

Treatment satisfaction was measured after treatment termination on a 7-point Likert-type scale, ranging from 1 (very dissatisfied) to 7 (very satisfied). Overall, treatment satisfaction in this study was relatively high, and there were no differences between the CIT-S (M = 6.08, SD = 0.93) and PSY-ED (M = 5.83, SD = 1.68) conditions on treatment satisfaction, t(44) = .63, p = .535. Similarly, an ANCOVA, controlling for treatment type, indicated no differences in matched versus mismatched groups on treatment satisfaction, F(1, 43) = .34, p = .561 (satisfaction in matched therapist-patient dyads, M = 5.91, SD = 1.40, and mismatched therapist-patient dyads, M = 6.20, SD = .89). When reexamining this with minority groups further broken down by ethnicity and counting participant therapist dyads as a mismatch if they were both minorities but from different ethnic groups (e.g., Hispanic therapist and an African American client), results continued to indicate no differences in matched versus mismatched groups on treatment satisfaction, F(1, 43) = .44, p = .512 (satisfaction in matched therapist-patient dyads, M = 5.86, SD = 1.32, and mismatched therapist-patient dyads, M = 5.97, SD = 1.62).

Discussion

The overarching aim of this study was to test whether a family focused, culturally informed treatment for schizophrenia (CIT-S) was effective in lowering patients’ psychiatric symptoms. The study also examined whether treatment efficacy was moderated by ethnicity. With respect to our primary study hypothesis, results indicated that patients who completed CIT-S demonstrated significantly lower levels of symptom severity when compared to patients who completed PSY-ED, with a medium effect size. This effect appears in line with other family focused interventions (for review, see Pitschel-Walz, Leucht, Bäuml, Kissling, & Engel, 2001). The treatment appears to improve symptoms across domains; however, significant results were obtained only when using total BPRS scores. Thus, overall, our findings demonstrate the potential for a family focused intervention incorporating culturally informed components to have a moderately strong and significant positive effect on schizophrenia symptoms.

With respect to our secondary (exploratory) hypotheses, results were not found to be moderated by ethnicity. Thus, this treatment appears to work equally well for Whites and minorities alike. Also in line with the preponderance of research (e.g., Cabral & Smith, 2011), patient-therapist ethnic match does not appear to influence treatment efficacy. This finding is encouraging, especially given the shortage of ethnic minority mental health professionals currently available to provide treatment to patients with the illness (American Psychological Association, 2003). It is unclear from our study whether therapist-participant match on other cultural beliefs and values (e.g., family cohesion, collectivism, spirituality) may impact treatment efficacy. This area requires further exploration.

Although the treatment appears to work well, and our treatment adherence was excellent, it is noteworthy that approximately 33% of patients did not complete therapy and attrition rates did not differ between conditions. This rate is disturbing though not surprising in that schizophrenia and psychotic based disorders have the highest drop-out rate of any diagnosis (e.g., Hamilton, Moore, Crane, & Payne, 2011). Furthermore, minorities drop out of treatment significantly more often than do Whites (Austin & Wagner, 2006; Rich et al., 2013) and, of the treatment modalities, family therapy is associated with even higher dropout rates than individual therapy (Hamilton et al., 2011). Despite our large ethnic minority sample and family focused approach, our attrition rate is comparable to most other studies in schizophrenia (Balikci et al., 2013; Hamilton et al., 2011; Kurtz, Rose, & Wexler, 2011). More attention to barriers that may prevent both minority and nonminority schizophrenia patients from completing treatment are clearly needed in future research.

There were a number of limitations to the present study. First, CIT-S is 12 weeks longer than PSY-ED. Thus, it is unclear whether CIT-S would outperform a matched length empirically supported approach. A related limitation is that patients in the PSY-ED condition had their final assessment 13–14 weeks following therapy termination yet CIT-S patients had their termination assessment 1–2 weeks post treatment. This is because the study was designed to hold everything constant (including the assessment timeline) in both therapy conditions, with the exception of treatment type. While we generally view this as strength, it is possible that participants in the PSY-ED condition may have lost some of their therapy gains prior to their termination assessment. It will, therefore, be important in future research to evaluate whether CIT-S can outperform an already established matched length intervention for schizophrenia (e.g., family-focused therapy; Miklowitz & Goldstein, 1997), with all assessments conducted on the same timeline. Having multiple pre- and posttreatment assessments would further strengthen future research. This would allow for data imputation techniques to account for those who drop out during the study and would also offer the opportunity to assess whether treatment gains are maintained over time.

Another study limitation is that treatment assessors were not always blinded to the treatment condition because the study was managed by one central treatment team and, therefore, logistical and other issues were often discussed at weekly lab meetings. While the clear manualized guidelines that accompany the BPRS and the high reliability among raters make it unlikely that systematic bias was introduced, future studies would be enhanced by ensuring that assessors are always unaware of treatment condition. Another study limitation is that we did not directly assess cultural mechanisms of change in this study. We see this study as a first step in demonstrating that CIT-S is indeed worthy of further investigation. In future research, however, it will be critical to assess whether increases in the utilization of adaptive cultural practices and beliefs (e.g., family collectivism, spiritual coping techniques) directly drive the improvements that we see in patients who receive CIT-S. Finally, because the minority sample was predominantly Hispanic/Latino, our findings may not generalize to other minority groups.

In summary, our study findings demonstrate that CIT-S has the potential to reduce symptom severity for patients suffering from schizophrenia, and the treatment does not appear to be moderated by ethnicity. One reason this treatment may work for all ethnicities is that, while there is emphasis on pulling beliefs, values, and behaviors from one’s culture to help make sense of and manage the illness, we put few parameters on what these philosophies and practices may be (as long as we believe they can be utilized productively in therapy). In prior publications, we have offered illustrations of CIT-S with Hispanic/Latino and Black clients (e.g., Weisman, 2005). We will conclude this paper with a case illustration that demonstrates how the family collectivism module and the spirituality module of CIT-S might function in a White, Jewish family. Aliases are used and identifying information has been altered sufficiently to protect the identity of our participants.

Case Illustration

One of our White clients, Alan, age 27, came in for family therapy with his wife Michelle, (also age 27), and his mother-in-law, Judy, who lived with the couple. The family was randomized to CIT-S. Alan, Michelle, and Judy all strongly identified as Jewish. Alan and Michelle began dating when they were both in their first year of college and married 5 years later. Alan was a certified public accountant and had been gainfully employed but was no longer able to maintain his demanding job after an inpatient hospitalization that had occurred 18 months prior to coming to therapy.

In the family collectivism module, it became clear that the notion of family and family traditions, such as sharing meals and spending quality time together, were very salient for all three family members. Alan, who continued to display mild thought disorder and negative symptoms (i.e., blunted affect and avolition) since his hospitalization, reported feeling distressed that he was not able to provide for his family. When he described the culture of his family of origin, he explained that being diligent and productive were highly valued and felt that he was also letting down his own father who he viewed as an exemplary Jewish dad. While Judy and Michelle were both supportive of Alan taking a hiatus from working, they also expressed concerns that he had not been using his time productively. Alan spent most of his day in his slippers and pajamas, “tinkering” with and fixing broken appliances that people had discarded as junk. He was excellent at repairing the items and enjoyed making things work once again. While Michelle and Judy were impressed with Alan’s skill, they felt like he was not doing enough to help move the family forward. During discussions in the family collectivism module of therapy, the family came up with the idea that Alan could sell appliances that he had repaired. The first few sales lifted Alan’s spirits and gave him increased motivation and hope that he would be able to provide for his family. It also appeared to bring the family closer together. Both Judy and Michelle (and a few other members of their extended family) began assisting in identifying objects on craigslist and in helping to make “business” transactions. Alan’s extended family started referring to him as “Mr. Fix-It,” which he felt reflected their love and support for him. He experienced a surge in his confidence.

The Jewish faith and practices were extremely important to Alan, Judy, and Michelle. However, once Alan became ill, he had stopped going to temple and became more isolated. The spirituality module really resonated with both Alan and Michelle. It made them realize how much they missed participating in their religious community. In therapy, they were asked to bring in spiritual quotes or materials that spoke to them. Alan came across a Jewish proverb: “The man who gives little with a smile gives more than the man who gives much with a frown.” After being diagnosed with schizophrenia, Alan felt that he could no longer meaningfully contribute to society, but rediscovering this proverb allowed him to think about the limitations imposed by his illness in a different manner. He felt inspired to help in his community and hoped that just being there for someone with a helping hand and a smile could make a difference. Alan recounted that doing charity work was a value that had been instilled in him since Hebrew school. Alan and Michelle began serving food at the local soup kitchen. Here, Alan had a chance to put the Jewish proverb to use and this helped him indirectly address the issue of flat affect that had lingered since his hospitalization. Through therapy and through becoming more involved in his community, Alan expressed feeling a greater sense of interconnectedness to his family and to his community.

In the other modules, skills to maintain these gains were reinforced. For example, in the communication training and the problem solving modules, techniques were practiced to help Alan engage with others outside of the family more effectively and to increase the likelihood that his new business venture (repairing appliances) would succeed. In the education module, the importance of adhering to his medication was stressed along with the importance of maintaining a low key supportive environment to help Alan remain in remission. Alan’s mood, affect, and cognition appeared markedly improved at treatment termination and Alan’s wife and mother-in-law also reported feeling happier and less burdened by Alan’s illness.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the National Institute of Health (R34 5R34MH7) and by the University of Miami, Department of Psychology/Fred C. and Helen Donn Flipse Research Support Fund. We thank the patients and families who participated in this randomized trial. We also thank all of the therapists and other research assistants who helped carry out this project.

References

- American Psychological Association. (2003). Guidelines on multicultural education, training, research, practice, and organizational change for psychologists. American Psychologist, 58, 377–402. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.58.5.377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Austin A, & Wagner EF (2006). Correlates of treatment retention among multi-ethnic youth with substance use problems: Initial examination of ethnic group differences. Journal of Child & Adolescent Substance Abuse, 15, 105–128. doi: 10.1300/J029v15n03_07 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Balikci A, Erdem M, Zincir S, Bolu A, Zincir S, Ercan S, & Uzun O (2013). Adherence with outpatient appointments and medication: A two-year prospective study of patients with schizophrenia. Klinik Psikofarmakoloji Bülteni/Bulletin of Clinical Psychopharmacology, 23, 57–64. doi: 10.5455/bcp.20121130085931 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barrio C, & Yamada A (2010). Culturally based intervention development: The case of Latino families dealing with schizophrenia. Research on Social Work Practice, 20, 483–492. doi: 10.1177/1049731510361613 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black L (1996). Families of African origin: An overview In McGoldrick M, Giordano J, & Pearce JK (Eds.), Ethnicity and family therapy (2nd ed; pp. 57–65). New York, NY: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cabral RR, & Smith TB (2011). Racial/ethnic matching of clients and therapists in mental health services: A meta-analytic review of preferences, perceptions, and outcomes. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 58, 537–554. doi: 10.1037/a0025266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson R, & Weisman de Mamani A (2010). Client characteristics and therapist competence and adherence to family therapy for schizophrenia. Interamerican Journal of Psychology, 44, 203–212. [Google Scholar]

- Culver JL, Arena PL, Wimberly SR, Antoni MH, & Carver CS (2004). Coping among African-American, Hispanic, and non-Hispanic White women recently treated for early stage breast cancer. Psychology & Health, 19, 157–166. doi: 10.1080/08870440310001652669 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon L, Adams C, & Lucksted A (2000). Update on family Psychoeducation for schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 26, 5–20. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a033446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon LB, Dickerson F, Bellack AS, Bennett M, Dickinson D, Goldberg RW, … Kreyenbuhl J (2010). The 2009 schizophrenia PORT psychosocial treatment recommendations and summary statements. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 36, 48–70. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbp115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon L, McFarlane W, Hornby H, & McNary S (1999). Dissemination of family psychoeducation: The importance of consensus building. Schizophrenia Research, 36, 339. doi: 10.1016/S0920-9964(99)90042-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dyck D, Short RA, Voss W, Hendryx MS, Hanken M, & Vitaliano P (2002). Service use among patients with schizophrenia in psychoeducational multifamily group treatment. Psychiatric Services, 53, 749–754. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.53.6.749 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falloon IRH, Boyd JL, & McGill CW (1984). Family care of schizophrenia: A problem solving approach to the treatment of mental illness. New York, NY: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, & Williams JBW (2002, November). Structured clinical interview for DSM–IV–TR Axis I Disorders, Research Version, Patient Edition (SCID-I/P). New York, NY: Biometrics Research, New York State Psychiatric Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Geisinger KF (1994). Cross-cultural normative assessment: Translation and adaptation issues influencing the normative interpretation of assessment instruments. Psychological Assessment, 6, 304–312. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.6.4.304 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Goldner EM, Hsu L, Waraich P, & Somers JM (2002). Prevalence and incidence studies of schizophrenic disorders: A systematic review of the literature. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry/La Revue Canadienne de Psychiatric, 47, 833–843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton S, Moore AM, Crane D, & Payne SH (2011). Psychotherapy dropouts: Differences by modality, license, and DSM–IV diagnosis. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 37, 333–343. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-0606.2010.00204.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kline RB (2011). Principles and practices of structural equation modeling (3rd ed.). New York, NY: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kopelowicz A, Zarate R, Wallace CJ, Liberman RP, López SR, & Mintz J (2012). The ability of multifamily groups to improve treatment adherence in Mexican Americans with schizophrenia. Archives of General Psychiatry, 69, 265–273. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuipers C (1993, March). Ethnic match and client characteristics as predictors of treatment duration and outcome among schizophrenics. Dissertation Abstracts International, 53, 9302715. [Google Scholar]

- Kurtz MM, Rose J, & Wexler BE (2011). Predictors of participation in community outpatient psychosocial rehabilitation in schizophrenia. Community Mental Health Journal, 47, 622–627. doi: 10.1007/s10597-010-9343-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lefley H (2009). Family psychoeducation in serious mental illness: Models, outcomes, applications. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. doi: 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195340495.001.0001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Leucht S, Kane JM, Kissling W, Hamann J, Etschel E, & Engel R (2005). Clinical implications of Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale scores. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 187, 366–371. doi: 10.1192/bjp.187.4.366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- López SR, Barrio C, Kopelowicz A, & Vega WA (2012). From documenting to eliminating disparities in mental health care for Latinos. American Psychologist, 67, 511–523. doi: 10.1037/a0029737 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lukoff D, Nuechterlein KH, & Ventura J (1986). Manual for the Expanded Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 12, 594–602. doi: 10.1093/schbul/12.4.578 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McFarlane WR (2002). Multifamily groups in the treatment of severe psychiatric disorders. New York, NY: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- McFarlane WR, Dixon L, Lukens E, & Lucksted A (2003). Family psychoeducation and schizophrenia: A review of the literature. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 29, 223–245. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-0606.2003.tb01202.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McFarlane WR, Lukens E, Link B, & Dushay R (1995). Multiple-family groups and psychoeducation in the treatment of schizophrenia. Archives of General Psychiatry, 52, 679–687. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1995.03950200069016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miklowitz DJ (2008). Bipolar disorder: A family-focused treatment approach (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Miklowitz DJ, & Goldstein MJ (1997). Bipolar disorder: A family-focused treatment approach. New York, NY: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Miranda J, Bernal G, Lau A, Kohn L, Hwang W, & LaFromboise T (2005). State of the science on psychosocial interventions for ethnic minorities. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 1, 113–142. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.1.102803.143822 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitsonis C, Voussoura E, Dimopoulos N, Psarra V, Kararizou E, Latzouraki E, … Katsanou M (2012). Factors associated with caregiver psychological distress in chronic schizophrenia. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 47, 331–337. doi: 10.1007/s00127-010-0325-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohr S, Perroud N, Gillieron C, Brandt P, Rieben I, Borras L, & Huguelet P (2011). Spirituality and religiousness as predictive factors of outcome in schizophrenia and schizo-affective disorders. Psychiatry Research, 186, 177–182. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2010.08.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueser KT, & Glynn SM (1999). Behavioral family therapy for psychiatric disorders (2nd ed.). Oakland, CA: New Harbinger. [Google Scholar]

- Mueser KT, & Jeste DV (2008). Clinical handbook of schizophrenia. New York, NY: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Murray-Swank AB, Lucksted A, Medoff DR, Yang Y, Wohlheiter K , & Dixon LB (2006). Religiosity, psychosocial adjustment, and subjective burden of persons who care for those with mental illness. Psychiatric Services, 57, 361–365. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.57.3.361 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nightingale MC (2003). Religion, spirituality, and ethnicity. Dementia: The International Journal of Social Research and Practice, 2, 380–391. doi: 10.1177/14713012030023006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Overall JE, & Gorham DR (1962). The brief psychiatric rating scale. Psychological Reports, 10, 799–812. doi: 10.2466/pr0.1962.10.3.799 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pharoah F, Mari J, Rathbone J, & Wong W (2004). Family interventions for schizophrenia. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 12, 98–103. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000088.pub3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinkham AE, Mueser KT, Penn DL, Glynn SM, McGurk SR, & Addington J (2012). Social and functional impairments In Lieberman JA, Stroup T, & Perkins DO (Eds.), Essentials of schizophrenia (pp. 93–130). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Pitschel-Walz G, Leucht S, Bauml J, Kissling W, & Engel RR (2001). The effect of family interventions on relapse and rehospitalization in schizophrenia: A meta-analysis. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 27, 73–92. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a006861 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rammohan AA, Rao K, & Subbakrishna DK (2002). Religious coping and psychological wellbeing in carers of relatives with schizophrenia. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 105, 356–362. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0447.2002.1o149.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Revheim N, Greenberg WM, & Citrome L (2010). Spirituality, schizophrenia, and state hospitals: Program description and characterisics of self-selected attendees of a spirituality therapeutic group. Psychiatric Quarterly, 81, 285–292. doi: 10.1007/s11126-010-9137-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rich BA, Hensler M, Rosen HR, Watson C, Schmidt J, Sanchez L, … Alvord MK (2013). Attrition from therapy effectiveness research among youth in a clinical service setting. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 41, 343–352. doi: 10.1007/s10488-013-0469-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson JT (2011). Eta squared and partial eta squared as measures of effect size in educational research. Educational Research Review, 6, 135–147. doi: 10.1016/j.edurev.2010.12.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rosmarin DH, Bigda-Peyton JS, Öngur D, Pargament KI, & Björgvinsson T (2013). Religious coping among psychotic patients: Relevance to suicidality and treatment outcomes. Psychiatry Research, 210, 182–187. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2013.03.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah R, Kulhara P, Grover S, Kumar S, Malhotra R, & Tyagi S (2011). Relationship between spirituality/religiousness and coping in patients with residual schizophrenia. Quality of Life Research: An International Journal of Quality of Life Aspects of Treatment, Care & Rehabilitation, 20, 1053–1060. doi: 10.1007/s11136-010-9839-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin S, Chow C, Camacho-Gonsalves T, Levy RJ, Allen I, & Leff H (2005). A meta-analytic review of racial-ethnic matching for African American and Caucasian American clients and clinicians. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 52, 45–56. doi: 10.1037/0022-0167.52.1.45 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shivashankar S, Telfer S, Arunagiriraj J, McKinnon M, Jauhar S, Krishnadas R, & McCreadie R (2013). Has the prevalence, clinical presentation and social functioning of schizophrenia changed over the last 25 years? Nithsdale Schizophrenia Survey revisited. Schizophrenia Research, 146, 349–356. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2013.02.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sota S, Shimodera S, Kii M, Okamura K, Suto K, Suwaki M, & Inoue S (2008). Effect of a family psychoeducational program on relatives of schizophrenia patients. Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences, 62, 379–385. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1819.2008.01815.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suro G, & Weisman de Mamani A (under review). The effect of a culturally-informed therapy for schizophrenia on self-conscious emotions and burden in caregivers of patients with schizophrenia. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabak N, & Weisman de Mamani A (2014). Religion’s effect on mental health in schizophrenia: Examining the roles of meaning-making and seeking social support. Clinical Schizophrenia & Related Psychoses, 8, 91–100. doi: 10.3371/CSRP.TUWE.021513 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarakeshwar N, Hansen N, Kochman A, & Sikkema KJ (2005). Gender, ethnicity and spiritual coping among bereaved HIV-positive individuals. Mental Health, Religion & Culture, 8, 109–125. doi: 10.1080/1367467042000240383 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tsang HH, Leung AY, Chung RK, Bell M, & Cheung W (2010). Review on vocational predictors: A systematic review of predictors of vocational outcomes among individuals with schizophrenia: An update since 1998. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 44, 495–504. doi: 10.3109/00048671003785716 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2001). Mental health: Culture, race, and ethnicity. A supplement to mental health: A report of the surgeon general. Rockville, MD: U. S. Department of Health and Human Services. [Google Scholar]

- Varela R, Sanchez-Sosa J, Biggs BK, & Luis TM (2009). Parenting strategies and socio-cultural influences in childhood anxiety: Mexican, Latin American descent, and European American families. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 23, 609–616. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2009.01.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ventura J, Nuechterlein KH, Subotnik KL, Gutkind D, & Gilbert EA (2000). Symptom dimensions in recent-onset schizophrenia and mania: A principal components analysis of the 24-item Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale. Psychiatry Research, 97, 129–135. doi: 10.1016/S0165-1781(00)00228-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisman AG (1997). Understanding cross-cultural prognostic variability for schizophrenia. Cultural Diversity and Mental Health, 3, 23–35. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.3.1.23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisman A (2005). Integrating culturally-based approaches with existing interventions for Hispanic/Latino families coping with schizophrenia. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training, 42, 178–197. doi: 10.1037/0033-3204.42.2.178 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Weisman A, Duarte E, Koneru V, & Wasserman S (2006). The development of a culturally informed, family-focused treatment for schizophrenia. Family Process, 45, 171–186. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2006.00089.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisman AG, & López SR (1996). Family values, religiosity, and emotional reactions to schizophrenia in Mexican and Anglo-American cultures. Family Process, 35, 227–237. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.1996.00227.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisman AG, Okazaki S, Gregory J, Tompson MC, Goldstein MJ, Rea M, & Miklowitz DJ (1998). Evaluating therapist competency and adherence to behavioral family management with bipolar patients. Family Process, 37, 107–121. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.1998.00107.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisman A, Rosales G, Kymalainen J, & Armesto J (2005). Ethnicity, family cohesion, religiosity and general emotional distress in patients with schizophrenia and their relatives. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 193, 359–368. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000165087.20440.d1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisman A, Tompson MC, Okazaki S, Gregory J, Goldstein MJ, Rea M, & Miklowitz DJ (2002). Clinicians’ fidelity to a manual-based family treatment as a predictor of the one-year course of bipolar disorder. Family Process, 41, 123–131. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2002.40102000123.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisman de Mamani A, Tuchman N, & Duarte EA (2010). Incorporating religion/spirituality into treatment for serious mental illness. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 17, 348–357. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpra.2009.05.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]