Abstract

Background

To address concerns about Veterans’ access to care at US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) healthcare facilities, the Veterans Access, Choice, and Accountability Act was enacted to facilitate Veterans’ access to care in non-VA settings, resulting in the “Veterans Choice Program” (VCP).

Objectives

To assess the characteristics of Veterans who used or planned to use the VCP, reasons for using or planning to use the VCP, and experiences with the VCP.

Design

Mixed-methods.

Subjects

After sampling Veterans in the Midwest census region receiving care at VA healthcare facilities, we included 4521 Veterans in the analyses. Of these, 60 Veterans participated in semi-structured qualitative interviews.

Approach

Quantitative data were derived from VA’s administrative and clinical data and a survey of Veterans including Veteran characteristics and self-reported use of VCP. Associations between Veterans’ characteristics and use or planned use of the VCP were assessed using logistic regression analysis. Interview data were analyzed using thematic analysis.

Key Results

Veterans with a higher odds of reporting use or intended use of the VCP were women, lived further distances from VA facilities, or had worse health status than other Veterans (P ≤ 0.01). Key themes included positive experiences with the VCP (timeliness of care, location of care, access to services, scheduling improvements, and coverage of services), and negative experiences with the VCP (complicated scheduling processes, inconveniently located appointments, delays securing appointments, billing confusion, and communication breakdowns).

Discussion

Our findings suggest that Veterans value access to care close to their home and care that addresses the needs of women and Veterans with poor health status. The Mission Act was passed in June 2018 to restructure the VCP and consolidate community care into a single program, continuing VA’s commitment to support access to community care into the future.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s11606-019-05224-y) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

KEY WORDS: Veterans, access to care, qualitative research, evaluation

INTRODUCTION

The Veterans Access, Choice, and Accountability Act was enacted in 2014 to facilitate Veterans’ access to care outside Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) healthcare facilities. The resulting “Veterans Choice Program” (VCP) was implemented in November 2014.1, 2 The VCP allowed VA to expand the availability of healthcare services for eligible Veterans through agreements with non-VA providers. Veterans enrolled in VA having wait times more than 30 days for VA healthcare appointments or living more than 40 miles from a VA medical center or community-based outpatient clinic would be eligible for care through non-VA providers. In May 2015, the Construction Authorization and Choice Improvement Act expanded VCP eligibility by redefining the 40-mile rule to include unusual and excessive burden for travel to VA healthcare facilities. Veterans may meet the 40-mile eligibility if travel is < 40 miles but involves geographic or environmental challenges such as mountain passes, roads through restricted areas (e.g., military bases), or hazardous weather conditions.3–5

In prior interviews about experiences with the VCP, staff and providers at VA facilities reported that the VCP was implemented with inadequate preparation, the community provider networks were insufficiently developed, and delays in care likely resulted from communication and scheduling problems with subcontractors.3 Veterans using the VCP reported improved access to care but using the VCP was a complex process.6 Additionally, studies of specific subgroups, such as women Veterans and Veterans with chronic hepatitis C virus, found that Veterans experienced difficulties in enrollment, ongoing support, and billing with third-party administrators, a lack of choice in location of treatment, and fragmented care that led to coordination challenges between VA and community providers.7, 8 Because ensuring access to healthcare for Veterans either within or outside of VA remains a priority of policymakers, it is important to understand who is seeking non-VA care and their experiences with that care. This study provides a unique perspective in that it used a mixed-methods design incorporating both quantitative and qualitative data. This study identifies factors and reasons associated with VCP use through quantitative analysis of survey and administrative data and then triangulates these reasons with Veterans’ perspectives from the qualitative analyses to provide further insight into these reasons.

METHODS

Study Design and Sample

We used a mixed-methods convergent design9 to gather complementary data to assess Veterans’ use of and experiences with the VCP. This design entails gathering and analyzing quantitative and qualitative data separately, then comparing the results to triangulate findings and examine the extent to which the two forms of data converge or diverge. The quantitative data derived from VA’s administrative and clinical data and a survey of Veterans in the Midwest census region of the USA. Qualitative data derived from semi-structured telephone interviews of 60 Veterans who participated in the survey and indicated their willingness to be interviewed.

We included Veterans age < 65 as of January 1, 2012, who were enrolled in VA healthcare any time during 2012 through 2014. We first conducted a stratified random sampling of those who were enrolled in VA before October 1, 2013. Strata were defined by gender, rural/urban residence, and three health conditions (mental health; severe illness, defined as diabetes with comorbidities; and disabilities, defined as a spinal cord injury or disorder [SCI/D]), all clinical subgroups of high interest to VA policymakers. To sample patients with mental health conditions, we identified Veterans with depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, or schizophrenia/other psychotic disorders using ICD-9 diagnosis codes established for identifying these conditions among Veterans.10–12 A patient was identified as having one of these mental health conditions if he/she had 1 inpatient or 2 outpatient diagnoses for that condition in a 12-month period. To sample patients with more severe illness, we identified Veterans with diabetes in VA clinical databases based on codes the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) uses to identify patients in the CMS chronic conditions data warehouse.13 To identify patients with SCI/D, we used a list of patients with SCI/D provided by the VA National SCI/D Program Office, which is derived from clinical patient records maintained at individual VA SCI Centers and other VA healthcare facilities.

From the patients identified above, we selected 5000 VA enrollees with mental health conditions, 5000 VA enrollees with diabetes with comorbidities, and 1000 VA enrollees with SCI/D due to the smaller population with this condition. Then, we randomly selected 5000 additional VA enrollees (regardless of health conditions) for a total of 16,000 Veterans enrolled before October 1, 2013. To incorporate the experiences of Veterans with less established relationships with VA into our analyses, we selected a random sample of 5000 Veterans who had enrolled in VA healthcare after October 1, 2013. Consequently, a total sample of 21,000 Veterans were sent an initial letter announcing the survey.

Among the 1446 survey respondents who expressed a willingness to be interviewed, we screened 145 Veteran respondents and conducted semi-structured interviews with 60 of them. The study was approved by a VA Institutional Review Board (IRB).

Mail Survey Procedures and Recruitment

The self-administered survey was conducted by mail following Dillman’s Tailored Design Method.14 Patient addresses were from the VA Corporate Data Warehouse (CDW). An announcement was sent to Veterans about the survey. Following the announcement and initial mailing of the survey, the survey was resent to non-respondents. A cover letter with the survey stated that survey responses would be linked with information in national VA and non-VA databases. Survey items about the VCP were part of a larger survey to assess Veterans’ insurance following implementation of the Affordable Care Act, use of non-VA services, and coordination of care between VA and non-VA providers. Survey questions were informed by previous work15 and discussions with Veterans Integrated Service Network (VISN) 12 leadership and the Office of the Assistant Deputy Under Secretary for Health (ADUSH). Before administering the survey, we conducted 17 cognitive or “think aloud” interviews with Veterans from the general medicine and relevant sub-specialty service lines at a VA medical center and associated outpatient clinics to assess patient understanding of survey questions. The survey instrument was refined from this feedback.

Semi-structured Interviews

Semi-structured telephone interviews were conducted between January 2017 and July 2017 to elucidate Veterans’ experiences with non-VA healthcare. Interview topics were derived from discussions with clinical and policy leadership, and included reasons that Veterans might choose to use the VCP, experience receiving non-VA care through VCP, and coordination of care within and across healthcare systems. Researchers trained in qualitative methods conducted the interviews. Interviews lasted approximately 60 min and were audio-recorded. Verbal informed consent was obtained at the beginning of each interview. Survey and interview guide questions pertinent to this study are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Survey Items and Interview Questions About Veterans Choice Program

| Survey items | |

| Have you received healthcare services outside of the VA through the Veterans Choice Program? | |

| Yes, I received healthcare services outside of the VA through the Veterans Choice Program | |

| No, but I plan to receive healthcare services outside of the VA through the Veterans Choice Program | |

| No, I did not receive healthcare services outside of the VA through the Veterans Choice Program and I do not plan to | |

| I am not sure | |

| Other | |

| What is your main reason for using or planning to use the Veterans Choice Program to get healthcare services outside of the VA? CHECK ONLY ONE | |

| I could not see my regular VA provider | |

| I wanted to access care closer to my home | |

| I was frustrated with having to wait for an appointment at the VA | |

| I was frustrated with the level of care at the VA for certain services | |

| It was hard to get in contact with the right person when calling the VA | |

| I needed specialty care services that were not available at my closest VA facility | |

| I was encouraged to use the Program by someone I talked to at the VA or someone affiliated with the VA | |

| I had medical issue(s) that needed immediate attention and the wait time was too long at my VA facility | |

| Other | |

| Interview questions | |

| How familiar are you with the Veterans Choice Act or VCA? Did you sign-up to receive healthcare services outside of VA through the Veterans Choice Act or VCA? | |

| Tell me about your reasons for signing up/not signing up for health services through VCA? | |

| Of these reasons, which are the most important to you or had the greatest influence on your decision? | |

| How do the healthcare services you receive in VA compared to those you receive outside of VA? | |

| Are there steps that you take, as a patient, to help your VA providers and non-VA providers talk to each other about your care? | |

| How do your different providers from inside and outside the VA talk with one another? |

Administrative and Clinical Data Sources

We supplemented information from the surveys with demographic and health status information from the VA Corporate Data Warehouse (CDW) and Medicare data. Health status was assessed using hierarchical condition category (HCC) risk scores divided into quartiles.16 Additional data included the VA ADUSH Enrollment file,17 which we used to obtain Veterans’ priority categories indicating whether Veterans were subject to VA copayments, and VA enrollment date. ZIP code information was used to determine distance to the nearest VA and Medicare facilities and rural/urban status, based on Rural-Urban Commuting Area (RUCA) codes.

Quantitative Analyses

To describe Veterans’ characteristics, continuous variables were analyzed using t tests, and categorical variables were analyzed using chi-squared tests. The association of Veterans’ characteristics with interest in the VCP (as indicated by having used or planning to use the VCP) was assessed using multivariable logistic regression analysis. Variables in the logistic regression model were included as categorical variables except for years enrolled in VA, which we included as a continuous variable. We presented the percentage of Veterans reporting each reason for using the VCP from the survey. Reasons were not mutually exclusive. Survey responses were weighted to account for sample design and non-response.18 Analyses were conducted in Stata version 14.2 (College Station, TX).

Qualitative Analysis

Audio-recorded interviews were transcribed verbatim. Qualitative analysis entailed thematic content analysis involving the iterative process of searching for themes and patterns emergent from the data through using the constant comparative method.19, 20 The qualitative software analysis program NVivo (QSR International Pty Ltd. Version 11.0, 2010) was used to guide analyses. Codes were initially developed deductively based on topics addressed in the interview guide.21 Within the topical categories, emergent subcodes were inductively developed and defined in a codebook until reaching saturation. To ensure rigor in this process, two researchers independently coded a subset of transcripts and then compared subcodes, resolving coding discrepancies through discussion until reaching consensus. Both researchers then used the codebook to code the entire dataset. Representative quotations are presented to illustrate key points. We followed COREQ guidelines in reporting our qualitative methods and results.22

RESULTS

Among the 21,000 Veterans in our initial sample, 2146 were subsequently determined to be deceased, have an incorrect address, or declined to participate in the study following the initial announcement letter and as a result were never sent a survey (online Appendix). Among the 18,854 Veterans in our final sample, there were 4525 respondents for a response rate of 24%. After removing those with incomplete data, 4521 respondents were available for the current analyses. Based on their survey responses, 2989 reported interest in the VCP (i.e., use or intended use).

Veterans using or planning to use the VCP were similar to Veterans without VCP use in age (52.3 versus 50.9 years, P = 0.10), race (18.2% versus 18.9% African American, P = 0.79), and distance to the nearest VA facility (22.0 versus 20.5 miles, P = 0.31) but were more likely to be women Veterans (14.3% versus 7.8%, P < 0.001) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Patient Characteristics

| No choice* (n 2989) | Choice* (n = 1532) |

P value | Interview participants % (N) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age years, mean | 50.9 | 52.3 | 0.10 | 54.7 |

| Age, % | 0.57 | |||

| ≤ 35 | 15.4 | 12.9 | 6.7 (4) | |

| > 35 to ≤ 45 | 12.2 | 11.4 | 10.0 (6) | |

| > 45 to ≤ 55 | 25.6 | 24.0 | 28.3 (17) | |

| > 55 | 46.9 | 51.7 | 55.0 (33) | |

| Gender, % | < 0.001 | |||

| Female | 7.8 | 14.3 | 41.7 (25) | |

| Male | 92.0 | 85.7 | 58.3 (35) | |

| Other | 0.2 | 0.03 | ||

| Race, % | ||||

| White | 78.8 | 77.7 | 0.78 | 95.0 (57) |

| African American | 18.9 | 18.2 | 0.79 | 5.0 (3) |

| Other | 2.5 | 4.0 | 0.01 | 6.7 (4) |

| Missing | 3.0 | 4.0 | 0.79 | 0 |

| Hispanic ethnicity, % | 0.06 | |||

| Hispanic ethnicity | 2.3 | 2.3 | 0 | |

| Ethnicity missing | 4.4 | 1.6 | 0 | |

| Enrollment priority, % | 0.38 | |||

| High disability | 23.5 | 25.2 | 31.7 (19) | |

| Low/moderate disability | 26.0 | 22.3 | 21.7 (13) | |

| Low income | 34.6 | 32.9 | 33.3 (20) | |

| Non-disabled, copayment required | 15.9 | 19.7 | 13.3 (8) | |

| Years enrolled in VA, mean | 9.5 | 10.1 | 0.05 | |

| Education, % | 0.35 | |||

| High school or less | 26.5 | 23.5 | 18.3 (11) | |

| Associate’s degree | 14.3 | 16.4 | 13.3 (8) | |

| Some college or technical school | 34.6 | 36.9 | 40.0 (24) | |

| Bachelor’s degree or higher | 21.0 | 21.7 | 28.3 (17) | |

| Missing | 3.7 | 1.5 | ||

| Marital status, % | 0.22 | |||

| Married | 42 | 41.0 | 46.7 (28) | |

| Not married | 53.6 | 56.9 | 53.3 (32) | |

| Missing | 4.3 | 2.2 | ||

| Number of children, % | 0.91 | |||

| 0 | 56.5 | 57.7 | 65.0 (39) | |

| 1 | 17.2 | 16.7 | 10.0 (6) | |

| 2 | 12.4 | 10.8 | 13.3 (8) | |

| > 2 | 9.0 | 9.1 | 10.0 (6) | |

| Missing | 5.0 | 5.8 | 1.7 (1) | |

| Distance to nearest VA facility miles, mean | 20.5 | 22.0 | 0.31 | 28.2 |

| Distance to nearest VA facility, % | 0.04 | |||

| < 5 miles | 36.1 | 27.0 | 23.3 (14) | |

| ≥ 5 to < 20 miles | 27.6 | 34.7 | 25.0 (15) | |

| ≥ 20 to < 40 miles | 18.1 | 21.0 | 25.0 (15) | |

| ≥ 40 to < 60 miles | 9.6 | 8.7 | 25.0 (15) | |

| ≥ 60 miles | 8.2 | 8.2 | 13.3 (8) | |

| Missing | 0.4 | 0.4 | 13.3 (8) | |

| Distance to nearest Medicare facility miles, mean | 8.1 | 8.5 | 0.20 | 10.8 |

| Distance to nearest Medicare facility, % | < 0.001 | |||

| < 5 miles | 44.9 | 33.8 | 25.0 (15) | |

| ≥ 5 to < 20 miles | 48.3 | 61.4 | 63.3 (38) | |

| ≥ 20 to < 40 miles | 6.4 | 4.4 | 11.7 (7) | |

| ≥ 40 to < 60 miles | 0.01 | 0.04 | ||

| ≥ 60 miles | 0 | 0 | ||

| Missing | 0.4 | 0.4 | ||

| Rural, % | 28.2 | 34.4 | 0.06 | 55.00 (33) |

| Household income, % | 0.32 | |||

| <$10,000 | 15.9 | 13.1 | 18.3 (11) | |

| $10,001 to $50,000 | 60.1 | 65.8 | 55.0 (33) | |

| >$50,000 | 18.1 | 13.4 | 26.7 (16) | |

| Missing | 5.9 | 7.7 | ||

| Non-VA Insurance in 2015, % | ||||

| None | 64.2 | 67.6 | 0.36 | 30.0 (18) |

| Private insurance (group) | 14.7 | 11.3 | 0.15 | 16.7 (10) |

| Tricare | 8.6 | 7.1 | 0.36 | 16.7 (10) |

| Medicare | 5.5 | 5.2 | 0.82 | 8.3 (5) |

| Medicaid | 5.2 | 4.5 | 0.55 | 23.3 (14) |

| Other | 2.5 | 1.4 | 0.19 | 1.7 (1) |

| Private insurance (individual) | 1.7 | 4.5 | 0.21 | 6.7 (4) |

| Insurance due to ACA | 0.9 | 1.1 | 0.74 | 15.0 (9) |

| Unknown | 0.7 | 0.8 | 0.87 | 0 |

| Hierarchical condition category risk score quartiles | 0.01 | |||

| 1 | 33.4 | 23.1 | 11.7 (7) | |

| 2 | 24.5 | 29.0 | 31.7 (19) | |

| 3 | 26.4 | 26.9 | 26.7 (16) | |

| 4 | 15.7 | 21.1 | 30.0 (18) | |

*Percents have been weighted to adjust for sample design and non-response

Factors Associated with Use of VCP

Results from logistic regression analysis indicated that male Veterans had 47% lower odds of VCP use or intended use than women Veterans (OR = 0.53, 95% CI 0.36 to 0.78, P = 0.001) (Table 3). Distance was also associated with the odds of using or intending to use the VCP. Compared with Veterans living < 5 miles from a VA facility, Veterans living 5 to 40 miles from a VA facility had greater odds of VCP use or intended use. Furthermore, living 5 to 20 miles from a healthcare facility reimbursed by Medicare was associated with greater VCP use or intended use. However, the greatest distances (> 40 miles) from either VA or Medicare-reimbursed facilities were not associated with significantly greater odds of VCP use or intended use. Additionally, health status was associated with VCP use or intended use. Compared with Veterans with the lowest HCC risk scores, Veterans with the highest risk scores had 76% greater odds of VCP use or intended use (OR = 1.76, 95% CI, 1.13 to 2.75, P = 0.01).

Table 3.

Factors Associated with Use or Planned Use of Veterans Choice Program

| Odds ratio (95% CI) | P value | |

|---|---|---|

| Age | ||

| ≤ 35 | Ref | |

| > 35 to ≤ 45 | 0.96 (0.48 to 1.92) | 0.90 |

| > 45 to ≤ 55 | 1.05 (0.59 to 1.86) | 0.88 |

| > 55 | 1.07 (0.59 to 1.95) | 0.83 |

| Gender | ||

| Female | Ref | |

| Male | 0.53 (0.36 to 0.78) | 0.001 |

| Other | 0.07 (0.01 to 0.87) | 0.04 |

| Race | ||

| White | Ref | |

| African American | 1.17 (0.79 to 1.72) | 0.43 |

| Other | 1.52 (1.03 to 2.25) | 0.03 |

| Missing | 1.06 (0.22 to 4.88) | 0.95 |

| Hispanic ethnicity | ||

| Not Hispanic | Ref | |

| Hispanic ethnicity | 0.84 (0.35 to 2.01) | 0.70 |

| Ethnicity missing | 0.30 (0.11 to 0.84) | 0.02 |

| Enrollment priority | ||

| High disability | Ref | |

| Low/moderate disability | 0.86 (0.61 to 1.22) | 0.40 |

| Low income | 0.90 (0.62 to 1.31) | 0.59 |

| Non-disabled, copayment required | 1.11 (0.73 to 1.70) | 0.61 |

| Years enrolled in VA, mean | 1.02 (0.997 to 1.05) | 0.09 |

| Education | ||

| High school or less | Ref | |

| Associate’s degree | 1.12 (0.76 to 1.65) | 0.59 |

| Some college or technical school | 1.22 (0.92 to 1.63) | 0.17 |

| Bachelor’s degree or higher | 1.36 (0.91 to 2.02) | 0.13 |

| Missing | 0.31 (0.07 to 1.43) | 0.13 |

| Marital status | ||

| Not married | Ref | |

| Married | 0.90 (0.68 to 1.18) | 0.44 |

| Missing | 0.79 (0.35 to 1.79) | 0.58 |

| Number of children | ||

| 0 | Ref | |

| 1 | 0.999 (0.70 to 1.43) | 0.996 |

| 2 | 1.00 (0.67 to 1.50) | 0.99 |

| > 2 | 1.18 (0.72 to 1.94) | 0.52 |

| Missing | 2.01 (0.80 to 5.08) | 0.14 |

| Distance to nearest VA facility | ||

| < 5 miles | Ref | |

| ≥ 5 to < 20 miles | 1.47 (1.01 to 2.13) | 0.04 |

| ≥ 20 to < 40 miles | 1.47 (1.00 to 2.16) | 0.05 |

| ≥ 40 to < 60 miles | 1.13 (0.71 to 1.80) | 0.60 |

| ≥ 60 miles | 1.56 (0.93 to 2.65) | 0.10 |

| Missing | 1.15 (0.28 to 4.69) | 0.85 |

| Distance to nearest Medicare facility | ||

| < 5 miles | Ref | |

| ≥ 5 to < 20 miles | 1.57 (1.10 to 2.24) | 0.01 |

| ≥ 20 to < 40 miles | 0.78 (0.44 to 1.37) | 0.39 |

| ≥ 40 to < 60 miles | 3.15 (0.20 to 48.70) | 0.41 |

| Urbanicity | ||

| Urban | Ref | |

| Rural | 1.05 (0.77 to 1.44) | 0.74 |

| Household income | ||

| <$10,000 | Ref | |

| $10,001 to $50,000 | 1.26 (0.89 to 1.78) | 0.19 |

| >$50,000 | 0.92 (0.55 to 1.54) | 0.75 |

| Missing | 2.68 (1.34 to 5.35) | 0.01 |

| Non-VA insurance in 2015 | ||

| Insurance outside VA | Ref | |

| No insurance outside VA | 1.18 (0.90 to 1.55) | 0.22 |

| Hierarchical condition category risk score quartiles | ||

| 1 | Ref | |

| 2 | 1.31 (0.86 to 1.99) | 0.22 |

| 3 | 1.31 (0.85 to 2.02) | 0.22 |

| 4 | 1.76 (1.13 to 2.75) | 0.01 |

Reasons for Using VCP

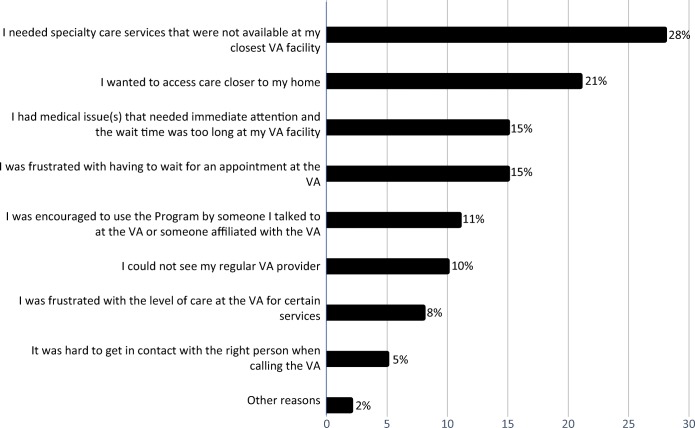

For those reporting VCP use or intended use (N = 1532), the most frequently reported reason was that Veterans needed specialty care services not available at their closest VA facility (28%) (Fig. 1). Many VCP users or intended users (21%) reported wanting access to care closer to home. Some users or intended users reported medical issues that needed immediate attention but wait times were too long at their VA facility (15%), and others reported frustration with having to wait for VA appointments (15%).

Figure 1.

Reason for using or planning to use the Veterans Choice Program. Figure 1 contains poor-quality text inside the artwork. Please do not re-use the file that we have rejected or attempt to increase its resolution and re-save. It is originally poor; therefore, increasing the resolution will not solve the quality problem. We suggest that you provide us the original format. We prefer replacement figures containing vector/editable objects rather than embedded images. Preferred file formats are eps, ai, tiff, and pdf.The original final is attached in .pptx format

Positive Experiences with VCP

Interview participants described positive and negative experiences with using the VCP to receive non-VA healthcare services. Regarding positive experiences, several themes were identified including timeliness of care, location of care, access to services, scheduling improvements, and coverage of services.

Timeliness of Care

Veterans reported positive instances where the VCP expanded opportunities for receiving care outside of the VA. For Veterans waiting more than 30 days for a VA appointment, the VCP allowed them to obtain non-VA care in a timelier manner. Accordingly, Veterans reported receiving care when they needed it rather than waiting for an available VA appointment:

I find that I get to go to the doctor sooner than if I were to wait for an appointment at the VA.

Location of Care

Veterans reported receiving care closer to their preferred location through VCP. Veterans stated that choosing the VCP gave closer options for care:

So I could have some options closer. Like I said, I can’t travel well and I’m not saying that they were better doctors, but I’m saying that I had more options for doctors.

Access to Services

Veterans reported receiving specialty care services that were not otherwise available at their local VA facility. In some circumstances, the VCP provided a helpful mechanism for Veterans to receive specialty care services at a non-VA facility instead:

There are some services that it’s just easier for me to get done outside of the VA. The VA hospital in my area does not cover my liver and stuff, because they don’t have a liver specialist on staff. As a result of that, I started using the Veteran’s Choice Program to go outside of the VA. And the fortunate part of that was my gastroenterologist is a member of the network for Choice, so I’d be able to continue to keep seeing my gastroenterologist through the Choice Program.

Scheduling Improvements

When the VCP was initiated, Veterans reported that there were some “growing pains,” but the process of using VCP to schedule and receive services had improved over time:

Yes, it’s gotten way better, it’s been really good the last couple of times I tried to use it. They’ve been great about finding doctors; when they couldn’t find the doctor that I wanted or asked for, then they’d call me right back and say that doctor is not available or something although we could get you somebody else.

Coverage of Services

Veterans reported that charges for services through VCP were being appropriately handled. Veterans appreciated that the VA was paying for services received through the VCP:

It has been working. It’s a little slow but yes, I’m happy with it. They are paying my bills for going outside the VA.

Negative Experiences with VCP

Some interview participants reported negative experiences with using the VCP including complicated scheduling processes, inconveniently located appointments, delays securing appointments, billing confusion, and communication breakdowns.

Complicated Scheduling Processes

Veterans reported challenges with scheduling appointments through VCP. They described the process as “vague” and “confusing.” Veterans also reported numerous redundant authorizations necessary to seek treatment through VCP resulted in frustration:

If you’ve got a lifelong sentence and you’re going to be stuck with this disease and there’s no cure for it, [community-based providers] shouldn’t have to be filling out forms every two to three months, six months, or whatever.

Inconveniently Located Appointments

Veterans reported that they sought care through the VCP to get it more conveniently. However, Veterans’ preferences were sometimes not met. For example, Veterans requested appointments at a specific location and/or a location closer to home and the VCP representatives did not accommodate their preferences:

I think what their problem is that they’ve been dinged for people having to wait too long for care, so in their effort in trying to get you scheduled quickly, they may not necessarily schedule you in kind of the right location… [I] f it does take a month to get, I’m willing to wait that long to get to this place that I want to go.

Delays Securing Appointments

Veterans reported waiting to receive services through VCP.

I’ve been having to get an endoscopy every three to four months… they still expect me to get a referral from the doctor where they can see I’ve been seeing the same doctor for the same issues that were approved.…[G]oing through the Choice program when they get the referral, because it has to go through so many layers to be approved, that I’ve waited for a procedure I needed immediately, I’ve waited two months.

Billing Confusion

Veterans reported VA facilities inappropriately handled charges for services through VCP:

I had one bill… the provider said that’s not covered through my VA because it was on the Choice program and my provider then sent it to [VA facility] which they sat on it. By the time they figured out they are supposed to send it to the Choice Program, I already had the bill in collections.

Communication Breakdowns

Some Veterans reported unresolved phone calls including holds, transfers, and hang-ups as well as limited explanations regarding the relationship of the VCP to Medicaid coverage. Although many Veterans reported receiving care quicker through the VCP, other Veterans experienced delays in securing appointments. The delays were attributed to the various referrals needed to get approval for VCP care and difficulties with communication:

You never talk to the same person twice. And that is a major issue! … I have never talked to the same person twice… one person explains it one way, and the other person explains it another way, and so, it can be frustrating.

DISCUSSION

This mixed-methods study of Veteran experiences with the VCP identified important associations between VCP use and gender, distance to VA facilities, and health status. Specifically, our quantitative analyses revealed that women were more likely to use the VCP, that distance to VA was associated with use of the VCP, and that those Veterans with worse health status were more likely to use the VCP. Our qualitative data corroborated these findings. Moreover, Veterans reported the importance of having specialized services that are available at a location close to home, and the VCP has addressed these issues for some Veterans. Veterans have reported that the VCP has resulted in improvements in timeliness and access to care. However, Veterans have also reported challenges with the VCP including complicated scheduling processes, inconveniently located appointments, and communication breakdowns. By identifying reasons for interest in the VCP through quantitative analyses and providing complementary insights into experiences with the VCP through qualitative analyses, this mixed-methods study gives a unique perspective on the VCP. Taken together, these results highlight the importance of obtaining continued feedback from Veterans.

A major finding was that women Veterans and those with more comorbidities had higher odds of VCP use or intended use compared with other Veterans. Prior research suggests that a substantially larger proportion of women Veterans receive non-VA healthcare compared with male Veterans.8, 23 Our findings may help explain the gender differences in VCP use. Many women Veterans who we interviewed reported using VCP for gender-specific services (e.g., mammograms). Moreover, survey participants’ leading reason for VCP use was the need for specialty care services not available at their closest VA facility. Because women comprise a minority of the VA population, accounting for approximately 8% of VA users, many gender-specific health services, such as mammography, and breast and cervical oncological services, may only be available in larger VA healthcare facilities with higher volumes of women Veterans. When gender-specific care is not available at a VA healthcare facility, the VCP allows Veterans to access non-VA care from community providers in VCP networks.8

Another key finding was the influence of distance on VCP use. Veterans preferred accessing care closer to their home and/or preferred location. There were unique differences in VCP use by distance to VA facilities. Those living 5 to 40 miles from their nearest VA healthcare facility were more likely to have interest in VCP than those living < 5 miles, but those living more than 40 miles away showed no difference compared with their closer counterparts. Rural areas tend to have fewer medical facilities compared with urban locations. For Veterans living more than 40 miles away from the nearest VA facility, there may not be many other non-VA facilities to be referred to through the VCP as these are likely to be more rural areas. Similarly, Ohl and colleagues found that VA played a greater role in providing healthcare for Veterans in counties over 40 miles from VA healthcare facilities compared with Veterans in counties within 20 miles of VA facilities.24

Veterans’ health status influenced the extent of VCP interest in that sicker individuals (i.e., higher HCC health risk scores) had higher odds of interest in VCP. This finding may be attributable to the added burden of travel or cumulative wait times experienced by Veterans needing more frequent visits. Veterans reported having medical issues that needed immediate attention but the wait time was too long at their VA facility. This finding highlights the importance of ensuring that Veterans with complex, chronic conditions are aware of and capable of leveraging the VCP for their needs.

Practice Implications

The Mission Act was passed into law in June 201825 to consolidate community care into a single program, continuing VA’s commitment to supporting access to community care. As the VCP is restructured through the Mission Act, it is imperative to find ways to improve the experiences of Veterans and the care that they receive from both VA and community-based facilities. Toward that end, Veterans’ experiences with community care could be improved in several ways.

A key improvement should focus on enhancing the communication between VA-referring providers and community-based providers seeing Veterans for care outside of the VA. The lack of communication and coordination between VCP providers and VA healthcare providers has been identified as a challenge in other qualitative studies investigating Veterans’ experiences with the VCP.6, 8 Designing and disseminating additional resources to support Veterans in their navigation of VA and community-based care may be useful. Our data suggest that Veterans could benefit from additional resources to help them coordinate care across systems such as dedicated case managers who would know Veterans and their needs on an individual level to advocate for them.

Another way to improve care is to align the priorities of VCP representatives with those of Veterans to better reflect the needs of Veterans. For example, Veterans noted that some VCP representatives might focus on providing a shorter time to the healthcare appointment while the Veteran’s priority might be shorter distances. In addition, some Veterans reported that VCP representatives may be differentially informed about the locations of potential referrals, and Veterans would like VCP representatives to be more cognizant of distance from referred location to the Veteran’s home. Although scheduling of community care visits for Veterans will be provided by VA rather than through private sector contractors under the Mission Act, it will still be useful for the VA schedulers to incorporate Veteran preferences in the scheduling process.

A further improvement may entail streamlining the process that Veterans must complete to secure VCP appointments. Veterans report that reductions in the number of steps between getting a referral to an outside facility and scheduling an appointment would be useful. Veterans reported that it would be helpful to understand how many visits their referral covered.

Limitations

The sample of Veterans was limited to the 12-state Midwest census region. Generalizability of the findings may be limited to the geographic area where the study was conducted. Additionally, there was a low (24%) response rate. We used weighting to adjust for the response rate but acknowledge this approach many not fully account for non-response. The analyses included Veterans who may have been unfamiliar with VCP because familiarity with the VCP was not assessed in the survey. At the time of our study, there were two large contractors that administered the VCP on a regional basis, Health Net and Triwest, and only Health Net provided services to the Midwest region. Consequently, the experiences of the Veterans in our sample may not necessarily reflect the experiences of those served by Triwest. However, the experiences of Veterans in our sample were consistent with the experiences reported in prior investigations.6–8

CONCLUSIONS

We found that gender, distance to VA facilities, and health status were associated with VCP use. While some Veterans appreciated the VCP’s access to services and timeliness of care, they remain concerned about the VCP’s communication challenges and inappropriately handled charges for services. Veterans’ experiences could be improved by enhancing the communication between VA and community-based providers, aligning the priorities of VCP representatives to better reflect the needs of Veterans, and streamlining the process that Veterans must complete to secure a VCP appointment. Future examination of the impact of the Mission Act on Veterans’ experiences may be warranted to assess whether challenges identified with the VCP have been addressed.

Electronic supplementary material

(DOCX 82 kb)

Funding Information

This study was supported by the Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Research and Development, Health Services Research and Development Service projects IIR 14-069 and SDR 17-155. Dr. Hynes received support as a VA Research Career Scientist RCS-98-352.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

The study was approved by the Edward Hines, Jr. VA Hospital Institutional Review Board (IRB)

Conflict of Interest

Drs. Stroupe, Gonzalez, Smith, and Weaver received grant funding from Medtronic Neurologic for work unrelated to this manuscript.

All remaining authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States government.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Veterans Access, Choice and Accountability Act of 2014 (“Choice Act” US Public Law 113–146). 2014. Available at: https://www.congress.gov/113/plaws/publ146/PLAW-113publ146.pdf. Accessed May 17, 2019.

- 2.Finley EP, Noël PH, Mader M, et al. Clinicians and the Veterans Choice Program for PTSD care: understanding provider interest during early implementation. Med Care. 2017;55:S61–S70. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mattocks KM, Mengeling M, Sadler A, Baldor R, Bastian L. The Veterans Choice Act: a qualitative examination of rapid policy implementation in the Department of Veterans Affairs. Med Care. 2017;55:S71–S75. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Department of Veterans Affairs. 38 CFR Part 17. Expanded access to non-VA care through the Veterans Choice Program. Federal Register, Vol. 80, No. 209. Thursday, October 29, 2015: 66420–66429. Available at https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2015-10-29/pdf/2015-27481.pdf. Accessed May 17, 2019. [PubMed]

- 5.Department of Veterans Affairs. 38 CFR Part 17. Expanded access to non-VA care through the Veterans Choice Program. Federal Register, Vol. 83, No. 92: 21893–21897. Available at: https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2018-05-11/pdf/2018-10054.pdf. Accessed May 17, 2019. [PubMed]

- 6.Sayre GG, Neely EL, Simons CE, Sulc CA, Au DH, Michael Ho P. Accessing care through the Veterans Choice Program: the Veteran experience. J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33:1714–1720. doi: 10.1007/s11606-018-4574-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tsai J, Yakovchenko V, Jones N, et al. “Where’s My Choice?” an examination of Veteran and provider experiences with hepatitis C treatment through the Veteran Affairs Choice Program. Med Care. 2017;55:S13–S19. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mattocks KM, Yano EM, Brown A, Casares J, Bastian L. Examining women Veteran’s experiences, perceptions, and challenges with the Veterans Choice Program. Med Care. 2018;56:557–560. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Creswell JW, Plano Clark VL. Designing and conducting mixed methods research. 2. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, Inc; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Frayne SM, Miller DR, Sharkansky EJ, et al. Using administrative data to identify mental illness: what approach is best? Am J Med Qual. 2010;25:42–50. doi: 10.1177/1062860609346347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gravely AA, Cutting A, Nugent S, Grill J, Carlson K, Spoont M. Validity of PTSD diagnoses in VA administrative data: Comparison of VA administrative PTSD diagnoses to self reported PTSD Checklist scores. JRRD. 2011;48:21–30. doi: 10.1682/JRRD.2009.08.0116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jordan N, Sohn MW, Bartle B, Valenstein M, Lee Y, Lee TA. Association between chronic illness complexity and receipt of evidence-based depression care. Med Care. 2014;52(Suppl 3):S126–31. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.CMS Chronic Conditions Data Warehouse (CCW) CCW Condition Algorithms. Available at https://aspe.hhs.gov/system/files/pdf/252376/AppendixA.pdf. Accessed 26 July 2019

- 14.Dillman DA. Mail and internet surveys: The tailored design methods. 2. New York: John Wiley & Sons,Inc.; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stroupe KT, Smith BM, Hogan TP, et al. Medication acquisition across systems of care and communication with providers by older Veterans. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2013;70:804–13. doi: 10.2146/ajhp120222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hynes DM, Koelling K, Stroupe K, et al. Veterans’ access to and use of Medicare and Veterans Affairs health care. Med Care. 2007;45:214–223. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000244657.90074.b7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.US Department of Veterans Affairs Information Resource Center. VIReC Research User Guide: VHA Assistant Deputy Under Secretary for Health (ADUSH) Enrollment Files. 2nd Edition. Hines IL: US Department of Veterans Affairs, Health Services Research & Development Service, Information Resource Center; Sept. 2013. Available at http://vaww.virec.research.va.gov/RUGs/ADUSH/RUG-ADUSH-EF-FY99-12-RA.pdf. Accessed 26 July 2019

- 18.Vallient R, Dever JA. Survey weights: a step-by-step guide to calculation. College Station: Stata Press; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lindlof R. Qualitative communication research methods. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Strauss A, Corbin JM. Basics of qualitative research: techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. 4. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bradley EH, Curry LA, Devers KJ. Qualitative data analysis for health services research: developing taxonomy, themes, and theory. Health Serv Res. 2007;42(4):1758–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2006.00684.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig JC. Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ): a 32 item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007;19:349–57. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzm042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Frayne SM, Phibbs CS, Saechao F, et al. Sourcebook: Women Veterans in the Veterans Health Administration. Volume 4: Longitudinal Trends in Sociodemographics, Utilization, Health Profile, and Geographic Distribution. Washington DC: Women’s Health Evaluation Initiative, Women’s Health Services, Veterans Health Administration, Department of Veterans Affairs; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ohl ME, Carrell M, Thurman A, et al. Availability of healthcare providers for rural veterans eligible for purchased care under the Veterans Choice ct. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18:315. doi: 10.1186/s12913-018-3108-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sisk R. Trump Signs $55 Billion Bill to Replace VA Choice Program. Military.com 2018. Available at: https://www.military.com/daily-news/2018/06/06/trump-signs-55-billion-bill-replace-va-choice-program.html. Accessed May 17, 2019.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOCX 82 kb)