Abstract

Background

Glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) is one of the most useful and relevant laboratory tests currently available. The aim of the actual research was to study the variability and appropriateness in the request of HbA1c in primary care, and differences between regions, to assess if there would be an opportunity to improve the request.

Methods

A cross‐sectional study was conducted enrolling clinical Spanish laboratories. The number of HbA1c requested in 2014 by all general practitioners was reported by each participant. Test‐utilization rate was expressed as tests per 1000 inhabitants. The index of variability was calculated, as the top decile divided by the bottom decile. HbA1c per 1000 inhabitants was compared between the different regions. To investigate whether HbA1c was appropriately requested to manage patients with diabetes, the real request was compared to the theoretically ideal number, according to prevalence of known diabetes mellitus in Spain and guideline recommendations.

Results

A total of 110 laboratories participated in the study, corresponding to a catchment area of 27 798 262 inhabitants (59.8% of the Spanish population) from 15 different autonomous communities (AACCs). 2 655 547 HbA1c were requested, a median of 93.9 (interquartile range (IQR): 33.4) per 1000 inhabitants. The variability index was 1.97. The HbA1c/1000 inhabitants was significantly different among the AACCs, ranging from 73.4 to 126.3.

A total of 4 336 529 additional HbA1c would have been necessary to manage patients with diabetes according to guidelines, and 3 861 769 for diagnosis in asymptomatic patients.

Conclusions

There was a high variability and significant differences between Spanish AACCs. Also a significant under‐request of HbA1c was observed in Primary Care in Spain.

Keywords: appropriateness, diabetes, glycated haemoglobin, laboratory tests utilization

Abbreviations:

- AACC

Autonomous community;

- GP

General practitioner;

- HbA1c

Glycated haemoglobin;

- HD

Health Department

1. INTRODUCTION

Glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) is one of the most useful and relevant laboratory tests currently available. Not just for monitoring diabetes to adjust treatment and avoid complications, but also for its diagnosis.1 This aspect is especially crucial in Europe, where the number of people with diabetes is estimated to be 59.8 million (9.1% of the population aged 20‐79), including 23.5 million undiagnosed cases.2 In addition to its power as a diagnostic and monitoring tool, HbA1c has many advantages when compared to other tests involved in diabetes management. HbA1c is an indicator of the glucose levels in the previous 3 months, it is not invasive, benefits from standardised methodology and sample stability, there is no gap between sample collection in primary care centres and laboratory analysis, and is very affordable.3 However the potency of any laboratory test, regardless of its intrinsic potential as a diagnostic, monitoring or detection tool, is given for the correct or incorrect use in each patient or specific setting.

In 2008, we first detected an inappropriate HbA1c over‐ and also under‐ request in patients with and without diabetes in eight health departments (HDs) in Valencia community.4 The same results were observed in every one of the primary care centres.5 Since 2010, two national scale studies to compare laboratory test ordering in Spain (REDCONLAB), further showed a high variability for HbA1c demand in primary care6 and a global, significant, and potentially dangerous under‐request.6, 7 In the earlier studies, not enough collaborators were available to compare the regional differences in the request between the Spanish autonomous communities (AACCs).

Given the crucial role of the test in diabetes diagnosis and management, especially in younger, healthy and newly diagnosed patients8 we considered the need for additional research.

Our hypothesis was that still the request of HbA1c from primary care is rather heterogeneous among HDs and could be different between Spanish Regions, which is a potential opportunity to improve the request.

The aim of the actual research was to study the variability and appropriateness in the request of HbA1c in primary care, and differences between regions.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

Every Spanish citizen possesses the Individual Health Care Card, which lets access to public health services throughout the National Health System. Spain is divided in 17 regions called AACCs composed by HDs that cover a geographic area and its population, and have several primary care centers, and usually a unique hospital with a laboratory to attend the needs of every HD inhabitant.

A call for data was posted via email and addressed to the participants of previous REDCONLAB studies. A LinkedIn group was created. (https://www.linkedin.com/in/redconlab-grupo-a5663bb7). Spanish laboratories willing to participate were invited to fill out an enrollment form and submit their results online.

Laboratories were required to obtain data from local Laboratory Information System Patient's databases and to provide organizational data. The number of HbA1c requested for 2014 by all general practitioners (GPs) was reported by each participant.

Test‐utilization rate was expressed as tests per 1000 inhabitants. The index of variability was calculated, as the top decile divided by the bottom decile (90th percentile/10th percentile).

Laboratories were grouped in the different AACCs, when more than 4 participants, and a group joining the results of the rest, and codified by numbers because of confidentiality. HbA1c per 1000 inhabitants was compared between the different AACCs.

To investigate whether HbA1c was appropriately requested to manage patients with diabetes, the real request was compared to the theoretically ideal number, according to prevalence of known diabetes mellitus in Spain (8.1%)9 and guideline recommendations (HbA1c test at least two times a year); it also was compared to the necessary amount to diagnose diabetes in asymptomatic patients (HbA1c every 3 years when older than 45), taking into account the demography of the Spanish population.10 The theoretically number of HbA1c tests was expressed in absolute numbers for the population studied, and as HbA1c per 1000 inhabitants. Each participant was also asked via email for the reagent price of HbA1c to calculate the medium cost of HbA1c and the overall incremental expenditure that would have been estimated for performing additional HbA1c to manage diabetic patients and for the diagnosis.

Descriptive statistics was generated for test‐utilization rate. The differences in the indicator between AACCs were calculated by way of Kruskal‐Wallis test analysis. A two‐sided P ≤ .05 rule was utilized as the criterion for rejecting the null hypothesis of no difference. All analyses were performed using SPSS for Windows, Version 22.0 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL, USA).

3. RESULTS

A total of 110 laboratories participated in the study, corresponding to a catchment area of 27 798 262 inhabitants (59.8% of the Spanish population) from 15 different AACCs. 2 655 547 HbA1c were requested, 93.9 (IQR: 33.4) per 1000 inhabitants. The variability index was 1.97.

A total of 4 336 529 HbA1c would have been necessary to manage patients with diabetes according to guidelines, and 3 861 769 for diagnosis in asymptomatic patients; 156 and 139 respectively when expressed per 1000 inhabitants.

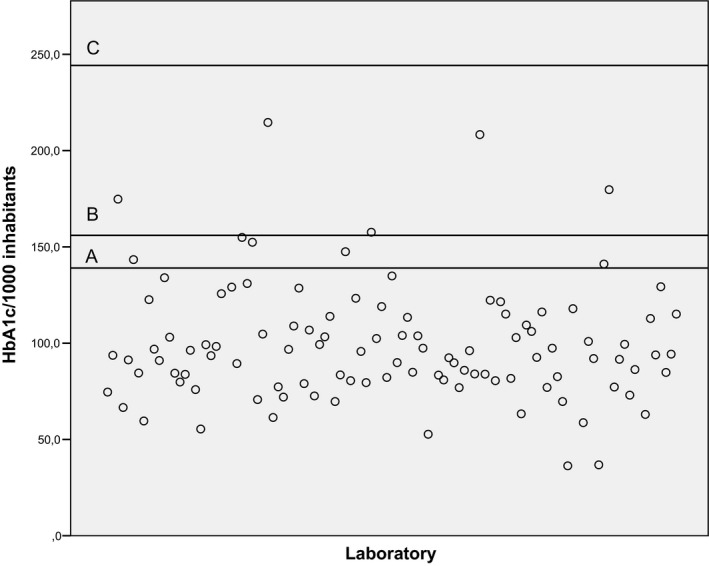

Figure 1 shows graphically the indicator result for every participant laboratory compared to the theoretical ideal values for diabetes management, diagnosis and both together. Five laboratories reached the management threshold, 10 the diagnostic and none reached both.

Figure 1.

Indicator result for every participant laboratory compared to objectives. Scattered plots showing the HbA1c/1000 inhabitants indicator results. Horizontal line displays the objectives values of indicator (A: Theoretical ideal values for diabetes diagnosis; B: Theoretical ideal values for diabetes management; C: Theoretical ideal values for diabetes management and diagnosis)

Fifty‐four (49.1%) laboratories reported the price of the HbA1c reagent; the average price per test (excluding VAT) was 1.28 ± 0.35€. Taking into account that cost, the expenditure for performing additional HbA1c to manage patients with diabetes would have been 5 550 757.1€, and 4 943 064.3€ for the diagnosis in asymptomatic patients.

Ten AACCs had more than 4 participants, and 5 did not reach the 4 contributors and conformed the eleventh group. The HbA1c/1000 inhabitants ratio was significantly different among the AACCs, ranging from 73.4 to 126.3 (Table 1). There are significant differences (P < .05) between AACC 1 and AACCs 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 9 and 11; between AACC 2 and AACCs 3, 4, 5, and 9; between AACC 4 and AACCs 7, 8, 10, and 11; between AACC 5 and AACC 6, 7, 8, 10 and 11; and between AACC 10 and AACC 11.

Table 1.

Request of HbA1c per Spanish regions

| HBA1C/1000 inhabitants | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N centers | Median | P25 | P75 | IQR | ||

| Autonomous communitie (anonymized) | 1 | 20 | 126.3 | 103 | 153.7 | 50.7 |

| 2 | 16 | 105.4 | 95.7 | 124 | 28.3 | |

| 3 | 10 | 86.1 | 73 | 95.7 | 22.7 | |

| 4 | 11 | 79.1 | 61.4 | 83.5 | 22.1 | |

| 5 | 12 | 76.9 | 66.6 | 84 | 17.4 | |

| 6 | 5 | 91.3 | 91 | 106.8 | 15.8 | |

| 7 | 5 | 96.9 | 83.8 | 98.3 | 14.5 | |

| 8 | 6 | 112.8 | 92.6 | 128.6 | 36 | |

| 9 | 6 | 73.4 | 58.7 | 96.1 | 37.4 | |

| 10 | 5 | 100.9 | 97.4 | 116.2 | 18.8 | |

| 11 | 14 | 89.6 | 83.4 | 96.3 | 12.9 | |

HbA1c/1000 inhabitants regarding autonomous communities.

4. DISCUSSION

A high variability and a significant burden of under‐request for HbA1c in every HD was observed, as demonstrated in previous studies.7 Differences were observed between AACCs, that almost doubled in the most demanding when compared to the one with the lowest demand. Close to three million HbA1c tests were requested in primary care in 60% of the Spanish population. However, more than eight million would have been necessary according to guideline recommendations. No single HD reached both the guideline goals to diagnose and manage the disease.

Although there is an overall over‐request of laboratory tests in primary care in Spain,11, 12, 13 HbA1c is a different scenario. This study shows a pattern similar to that observed in the previous REDCONLAB studies,7 with a significant burden of under‐requesting of HbA1c in all the 110 laboratories included in this survey. The fact that there are additional HbA1c uses in primary care, as arterial hypertension or subjects without diabetes <45 years with symptoms or family history could even aggravate the problem.

Individual initiatives for a better HbA1c request have been designed and established, as automatic laboratory‐based strategy to improve the diagnosis of type 2 diabetes in primary care.14 The obtained results, showing significant differences among AACCs, suggest however that the demand could be influenced by regional habits, and highlight that a major awareness and acknowledgement of this problem would be necessary to promote interventions at a regional scale for the best HbA1c request and consequently the best diabetes management and diagnosis.

A limitation of our study could be the difficulty of its application to non‐public environments, with no specific population or inhabitants to be covered.

There was a high variability and significant differences between Spanish AACCs. Also a significant under‐request of HbA1c was observed in Primary Care in Spain. The high prevalence of diabetes worldwide, the usefulness and easy availability of HbA1c, and potential automated strategies to improve demand based on laboratory information systems indicate the need to make efforts at a regional scale through communication and consensus for a better HbA1c request.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

MS, ML‐G, EF, and CL‐S conceived, designed and drafted the manuscript; MS, ML‐G, EF and CL‐S revised the final manuscript. All authors contributed to the concept, reviewed all versions of the manuscript and commented, and approved the final revised version of the manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Members of the REDCONLAB working group are the following: Vidal Pérez Valero (Hospital Regional Universitario de Málaga, Hospital Universitario Virgen de la Victoria, Málaga); Félix Gascón (Hospital Valle de los Pedroches, Pozoblanco); Isidoro Herrera Contreras (Complejo Hospitalario de Jaén); Maria Ángeles Bailen García (Hospital Universitario Puerta del Mar de Cádiz); Cristóbal Avivar Oyonarte (Hospital de Poniente, El Ejido); Esther Roldán Fontana (Hospital La Merced, A.G.S. de Osuna); Fernando Rodríguez Cantalejo (Hospital Universitario Reina Sofía de Córdoba); José Ángel Noval Padillo (Hospital Universitario Virgen del Rocío); M Ángela González García (AGS Norte de Cádiz); Ignacio Vázquez Rico (Hospital Juan Ramón Jiménez de Huelva); Cristina Santos (Hospital Rio Tinto); Ángeles Giménez Marín (Hospital de Antequera); Maria del Señor López Vélez (Hospital San Cecilio de Granada), José Vicente García Larios (Hospital Virgen de las Nieves, Granada); Federico Navajas Luque (AGS Este de Málaga‐Axarquía); Amado Tapia (Hospital de Barbastro); Maria Esther Solé LLop (Hospital de Alcañiz); Juan José Puente (Hospital Clínico Universitario Lozano Blesa); Patricia Esteve (Hospital Ernest Lluch); Maria Teresa Avello López (Hospital San Agustín‐Avilés, Hospital Valle del Nalón); Emilia Moreno Noguero (Hospital Can MIsses); Ana Maria Follana Vázquez (Hospital Mateu Orfila); Jose Luis Ribes Valles (Hospital de Manacor); Mª Luisa Fernández de Lis Alonso (Área de Salud de Fuerteventura); Mercedes Muros (Hospital Nuestra Señora de la Candelaria, Tenerife); Leopoldo Martin Martin (Hospital General de la Palma); Miguel Ángel Pico Picos (Hospital Universitario de Canarias); Casimira Domínguez Cabrera (Hospital Universitario de Gran Canaria Dr Negrín); Marta Riaño Ruiz (Hospital Insular de Gran Canaria); Juan Ignacio Molinos (Hospital Sierrallana de Torrelavega); Luis Fernando Colomo (Hospital de Laredo); Jose Carlos Garrido (Hospital Universitario Marqués de Valdecilla); Enrique Prada de Medio (Hospital Virgen de la Luz de Cuenca); Pilar García Chico (Hospital General Universitario de Ciudad Real); Simón Gómez‐Biedma (Hospital General de Almansa); jesus Dominguez (Hospital Universitario de Guadalajara); Guadalupe Ruiz (Complejo Hospitalario de Toledo); Laura Navarro (Complejo Hospitalario Universitario de Albacete); Fidel Velasco Pena (Hospital Virgen de Altagracia, Manzanares); Carolina Andrés Fernández (Hospital General de Villarobledo); Oscar Herráez Carrera (Hospital C.H. La Mancha Centro_Alcazar de San Juan); Mª Carmen Lorenzo Lozano (Hospital de Puertollano); Joaquín Domínguez Martínez y Oscar Herráez Carrera (Santa Barbara Hospital Gral. Mancha Centro y Hospital General de Tomelloso); Maria Teresa Gil (Hospital Nuestra Señora del Prado Talavera de la Reina); Mª Ángeles Rodríguez Rodríguez (Complejo Asistencial Universitario de Palencia (Hospital Rio Carrión); M. Victoria Poncela García (Hospital Universitario de Burgos); Luis Rabadán (Complejo Asistencial de Soria); Vicente Villamandos (Hospital Santos Reyes, Aranda del Duero); Nuria Fernández García (Hospital Universitario Rio Hortega‐Valladolid); José Miguel González Redondo (Hospital Santiago Apóstol de Miranda de Ebro); Cesáreo García (Hospital Universitario de Salamanca); Luis García Menéndez (Hospital El Bierzo); Pilar Álvarez Sastre (Complejo Asistencial de Zamora); Ovidio Gómez (Hospital Clínico Universitario de Valladolid); Mabel LLovet (Hospital Universitario Verge de la Cinta (Tortosa); Nuria Serrat (Hospital Joan XXIII de Tarragona); Mª José Baz (Hospital de Llerena, Badajoz); Maria José Zaro (Hospital Don Benito‐Villanueva); M Carmen Plata (Hospital Campo Arañuelo, Navalmoral de la Mata); Pura García Yun (Área de Salud de Badajoz (Hospital Infanta Cristina, Hospital Perpetuo Socorro y Hospital Materno Infantil)); Milagrosa Macías Sánchez (Área de Salud de Cáceres (Complejo Hospitalario San Pedro de Alcántara)); Javier Martin (Hospital Virgen del Puerto de Plasencia); Lola Máiz Suarez (Hospital Lucus Augusti, Lugo); Berta González Ponce (Hospital Da Costa, Burela); Concepcion Magadan (Hospital Arquitecto Marcide, El Ferrol); M. Amalia Andrade Olivie (Hospital Xeral‐Cies, CHU Vigo); Pastora Rodríguez (Hospital Universitario de A Coruña); M. Mercedes Herranz Puebla (Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Marañón); Antonio Buño Soto (Hospital Universitario La Paz, Madrid); Fernando Cava; Raquel Guillén Santos (BR Salud); Tomas Pascual (Hospital Universitario de Getafe); Carmen Hernando de Larramendi (Hospital Severo Ochoa de Leganés); Raquel Blázquez Sánchez (Hospital de Móstoles); Pilar Díaz (Hospital 12 de Octubre, Madrid); Ana Díaz (Hospital Universitario de La Princesa); Marta García Collía (Hospital Ramón y Cajal, Madrid); Maria Ángeles Cuadrado Cenzual (Hospital Clinico San Carlos); Santiago Prieto Menchero (Hospital Universitario de Fuenlabrada); María del Carmen Gallego Ramírez (Hospital Rafael Méndez, Lorca); José Luis Quilez Fernández (Hospital Universitario Reina Sofía de Murcia); Maria Dolores Albaladejo (Hospital Santa Lucia, Cartagena); Maria Luisa López Yepes (Hospital Virgen del Castillo de Yecla); Alfonso Pérez Martínez (Hospital Morales Meseguer); Antonio López Urrutia (Hospital de Cruces, Bilbao); Adolfo Garrido Chércoles (Hospital Universitario de Donostia); Carmen Mar Medina (Hospital Galdakao‐Usonsolo); M Carmen Zugaza (Unidad de Gestión Clínica de Álava); Manuel de Eguileor (Hospital Universitario de Basurto); Silvia Pesudo (Hospital La Plana); Carmen Vinuesa (Hospital de Vinaros); Julián Díaz (Hospital Francesc de Borja, Gandia); Marisa Graells (Hospital General Universitario de Alicante); Diego Benítez Benítez (Hospital de Orihuela); Arturo Carratalá (Hospital Clínico Universitario de Valencia); Consuelo Tormo (Hospital General de Elche); Francisco Miralles (Hospital Lluis Alcanyis, Xativa); Amparo Miralles (Hospital de Sagunto); José Luis Barberà (Hospital de Manises); Juan Molina (Hospital Comarcal de La Marina, Villajoyosa); Martin Yago (Hospital de Requena); Mario Ortuño (Hospital Universitario de la Ribera (Alzira)); Maria José Martínez Llopis (Hospital de Denia); Nuria Estañ (Hospital Dr. Peset); Ricardo Molina (Hospital Virgen de los Lirios, Alcoy); Juan Antonio Ferrero (Hospital General de Castellón); Begoña Laiz Marro (Hospital Universitario y Politécnico La Fe de Valencia); Goitzane Marcaida (Consorcio Hospital General Universitario de Valencia).

Salinas M, López‐Garrigós M, Flores E, Leiva‐Salinas C. Glycated hemoglobin: A powerful tool not used enough in primary care. J Clin Lab Anal. 2018;32:e22310 10.1002/jcla.22310

Pilot Group of the Appropriate Utilization of Laboratory Tests members are presented in Acknowledgments section

REFERENCES

- 1. International Expert Committee TIE . International Expert Committee report on the role of the A1C assay in the diagnosis of diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2009;32:1327‐1334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. International Diabetes Federation . IDF Diabetes Atlas, 7th edn Brussels, Belgium: Nam Han Cho; 2015:1‐4. idf.org. 10.1289/image.ehp.v119.i03 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Florkowski C. HbA1c as a diagnostic test for diabetes mellitus—reviewing the evidence. Clin Biochem Rev. 2013;34:75‐83. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Salinas M, López‐Garrigós M, Carratala A, et al. [An evaluation of glycosylated hemoglobin requesting patterns in a primary care setting: a pilot experience in the Valencian Community (Spain)]. Endocrinol Nutr. 2011;58:219‐223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Salinas M, Lopez‐Garrigos M, Pomares F, et al. An evaluation of hemoglobin A1c test ordering patterns in a primary care setting. Lab Med. 2012;43:1‐5. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Salinas M, López‐Garrigós M, Tormo C, et al. Primary care use of laboratory tests in Spain: measurement through appropriateness indicators. Clin Lab. 2014;60:483‐490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Salinas M, López‐Garrigós M, Uris J, et al. A study of the differences in the request of glycated hemoglobin in primary care in Spain: a global, significant, and potentially dangerous under‐request. Clin Biochem. 2014;47:1104‐1107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Reusch JEB, Manson JE. Management of type 2 diabetes in 2017: getting to goal. JAMA. 2017;317:1015‐1016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Soriguer F, Goday A, Bosch‐Comas A, et al. Prevalence of diabetes mellitus and impaired glucose regulation in Spain: the Diabetes Study. Diabetologia. 2012;55:88‐93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Instituto Nacional de Estadística. www.ine.es

- 11. Salinas M, López‐Garrigós M, Flores E, et al. Request of acute phase markers in primary care in Spain. Am J Manag Care. 2015;21:e591‐e596. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Salinas M, López‐Garrigós M, Flores E, et al. Request of laboratory liver tests in primary care in Spain: potential savings if appropriateness indicator targets were achieved. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;27:1130‐1136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Salinas M, López‐Garrigós M, Flores E, et al. Potential over request in anemia laboratory tests in primary care in Spain. Hematology. 2015;20:368‐373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Salinas M, Lopez‐Garrigos M, Flores E, et al. Automatic laboratory‐based strategy to improve the diagnosis of type 2 diabetes in primary care. Biochem Med. 2016;26:121‐128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]