Abstract

Background

Ostructive sleep apnea (OSA) is an independent risk factor for the development of cardiovascular events. Platelet activation and inflammation are the mechanisms involved in the association between OSA and cardiovascular disease (CVD). The markers of platelet activation and inflammation are the mean platelet volume (MPV), platelet‐lymphocyte ratio (PLR), red cell distribution width (RDW), neutrophil‐ lymphocyte ratio (NLR). We aimed to define the association of NLR, PLR, RDW, and MPV with the severity of disease and the presence of CVD.

Methods

This study consisted of 300 patients who were admitted to the sleep laboratory. The patients were classified according to their apnea‐ hypopnea index (AHI) scores as OSA negative (Group A: AHI<5), mild (Group B: AHI: 5‐15), moderate (Group C: AHI=15‐30), and severe OSA (Group D: AHI >30).

Results

There were no significant differences in the NLR, PLR, and MPV among the groups (P>.05); only RDW differed significantly (P=.04). RDW was significantly higher in patients with than without risk factors for CVD [15.6% (15.4‐15.7) vs 15.3% (15.1‐15.3), respectively; P=.02].

Conclusions

NLR, PLR, MPV, and RDW are widely available and easily obtained from a routinely performed hemogram. Among these laboratory parameters, only RDW can demonstrate the reverse consequences of OSA‐associated comorbidities, because vascular damage due to systemic inflammation is an important underlying mechanism in these diseases. RDW might be used as a marker of the response and patient compliance with continuous positive airway pressure treatment.

Keywords: cardiovascular disease, lymphocyte, neutrophil, obstructive sleep apnea, red cell distribution width

1. Introduction

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is characterized by the occurrence of daytime sleepiness, loud snoring, witnessed breathing interruptions or awakenings due to gasping or choking in the presence of at least five obstructive respiratory events (apneas, hypopneas, or respiratory related arousals) per hour of sleep collapse.1 The presence of 15 or more obstructive respiratory events per hour of sleep in the absence sleep related symptoms is also sufficient for the diagnosis of OSA. OSA is known to be associated with cardiovascular morbidity and mortality.2 OSA increases the risk of cardiovascular diseases (CVD) including hypertension, heart failure, arrhythmias, and coronary artery diseases.3 The pathogenesis is likely to be multifactorial process, including sympathetic nervous system excitation, vascular endothelial dysfunction, oxidative stress and inflammation.4 Recurrent pharyngeal collapse during sleep can lead to repetitive sequences of hypoxia‐reoxygenation, which induce activation of the proinflammatory factors IL‐6, C‐reactive protein (CRP) and TNF‐α.5 Inflammation is one of the fundamental factors contributing to the onset and progression of atherosclerosis.6 Significant roles of leukocytes in atherothrombosis are already known.7 Recently, neutrophil‐to‐lymphocyte ratios (NLR) and platelet‐to‐lymphocyte ratios (PLR) have emerged as potential new biomarkers that indicate the presence of inflammation. And also, they can single out individuals at risk for future cardiovascular events.8, 9

Low level systemic inflammation and hypercoagulability have been associated with OSA and coranary artery disease (CAD).10 Platelets exhibit a crucial linkage between thrombosis, inflammation, and atherogenesis by assembling to sites of vascular damage and inflammation. Mean platelet volume (MPV) has been shown to be indicator of platelet activation.11 And also, red blood cell distribution width (RDW) which is a numerical measure of the size variability of circulating erythrocytes, increases platelet activation. It was shown to be a strong independent predictor of morbidity and mortality in patients with chronic heart failure and in patients with coronary artery disease.12

Several studies have examined the relationship between PLR and RDW, NLR and RDW, MPV and RDW separately in OSA patients. However, the comparison between all of these parameters have not been determined in the same patient group to date. In this study, we analyzed the association of PLR, NLR, MPV, and RDW all together with the severity of the disease and the presence of cardiovascular diseases in patients with OSA.

2. Materials and Methods

This study consisted of 300 patients who were admitted to the sleep laboratory of our hospital between February 2013 and October 2014. Overnight polysomnography (Compumedics E series, Melbourne, Australia) was performed for all patients recording electroencephalogram, electrooculogram, submental electromyogram, bilateral anterior tibial electromyogram, electrocardiogram, chest and abdominal wall movement by inductance plethysmography, airflow measured by a nasal pressure transducer and supplemented by an oral thermister and finger pulse oximetry, snoring microphone and video monitoring using an infrared video camera. The recordings were scored according to the standard American Academy of Sleep Medicine (AASM) Task Force Criteria.13 Apnea was defined as a ≥90% decrease in the airflow amplitude persisting for at least 10 seconds relative to the baseline amplitude. Hypopnea was defined as a ≥50% decrease in the airflow amplitude relative to the baseline values associated with a ≥3% oxygen desaturation or arousal from sleep, all persisting for at least 10 seconds. The apnea hypopnea index (AHI) was calculated as the number of apneic plus hypopneic episodes per hour of sleep. Sleepiness was assessed by Epworth sleepiness scale (ESS) for each patient. We considered 10 the normal limit of ESS, as stated in its original version.14 The patients were classified according to their AHI as follows: OSA negative (Group A: AHI<5), mild (Group B: AHI:5‐15), moderate OSA (Group C: AHI: 15‐30) and severe OSAS (Group D: AHI>30). The oxygen desaturation index (ODI) was defined as the total number of measurements of oxyhemoglobin desaturation of ≥4% within ≥10 seconds to <3 minutes from the baseline, divided by the total sleep time.

Exclusion criteria were as follows: psychiatric causes of sleep disorder, central sleep apnea, use of sedatives and muscle relaxants, narcolepsy, age <18 years, liver or kidney disease, chronic alcoholism, malignacy, hyperthyroidism or hypothyroidism, inflammatory bowel disease, inflammatory connective tissue disorders, asthma, history of recent blood transfusion (within 2 weeks) and hematologic disorders such as leukemia, anemia, or myelodysplastic syndrome.

Demographic characteristics such as age, sex, and body mass index (BMI) were recorded. Cigarette smoking status, previous history of chronic diseases, drugs, and habits were obtained by a standardized questionnaire before the sleep study. The presence of diabetes mellitus (DM), hypertension (HT), or a smoking history was accepted as a cardiovascular risk factor. DM was defined as the patient having been informed of this diagnosis by a physician before admission or current treatment with hypoglycemic therapy (dietary treatment, oral antidiabetic agents, or insulin). HT was defined as a known elevation of blood pressure on at least two separate occasions according to the medical history or the use of antihypertensive medications in a patient with known controlled hypertension. CVD referred only to the presence of heart failure, coronary artery disease, or arrhythmia. Diagnosis of CVD was made by an expert cardiologist and the patients were being medically treated with one or more than one antiaggregants, antiischemic agents, beta blockers, angiotensin‐converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, angiotensin‐receptor blockers (ARB), or calcium antagonists.

The RDW, MPV, platelet, neutrophil, and lymphocyte counts were determined using the Abbott Cell‐Dyne 3700 Hematology Analyzer, as one part of a hemogram. The NLR and PLR were obtained from the absolute neutrophil and platelet counts, respectively, divided by the absolute lymphocyte counts.

2.1. Statistical analysis

All results were expressed as the mean±standard deviation. All analyses were done using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS), V. 15.0 (SPSS, Chiacago, IL, USA). A power analysis was conducted to determine the number of participants needed in the study. The α for the ANOVA will be set at <.012. The inclusion of minimum 25 participants per group provided 95% power for detecting differences in plasma RDW levels. The chi‐squared test was used for the comparison of qualitative variables. For quantitative variables, Kruskal–Wallis test was used when the number of groups exceeded two and but the data did not fit a normal distribution. Analysis of variance was used to compare more than two groups when the data fit the normal distribution. When there were significant differences among the groups, Mann–Whitney U test was used for multiple comparisons. The Spearman's test or Pearson's correlation was used to determine the relationships between variables. To establish RDW cut‐off value to distinguish between patients with or without CVD risk factors, receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis was performed and areas under curve were calculated. A P value of <.05 was considered satatistically significant.

3. Results

The clinical characteristics and laboratory parameters of the study population are summarized in Table 1. According to their AHI, patients were divided into Group A (n=52; 17.3%), Group B (n=53; 17.6%), Group C (n=65; 21.6%) and Group D (n=130; 43.3%). The mean age of the patients was 47.6±11.8 years and 75.6% (227) were male. Age and BMI gradually but significantly increased in parallel with the severity of OSA which was statistically significant (P<.01). The rates of DM and HT were significantly different among the groups (P<.01). And also, the rates of patients with CVD risk factors were significantly different among the groups (P=.03). However, Group D had a higher prevalence of CVD than the other three groups, the difference was not statistically significant. The use of ARBs/ACE inhibitors was significantly higher in Groups C (35%) and D (38%) than in Groups A (13%) and B (19%; P<.01). The patients in Group A used calcium antagonists significantly less frequently than the other groups (P=.02). There was no significant difference among the groups with respect to smoking. Additionally, the mean values of platelet, lymphocyte, neutrrophil counts; NLR; PLR and MPV did not show statistically significant levels among the four groups (P>.05). Only RDW differed significantly among the four groups (P=.04). RDW showed a significant increase in parallel with the severity of OSAS.

Table 1.

Demographic and laboratory findings of the study group

| Group A control group (n=52) | Group B mild OSA (n=53) | Group C moderate OSA (n=65) | Group D severe OSA (n=130) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (y) | 41±12 | 43±10 | 50±11 | 51±11 | <.01 |

| Gender, Male n (%) | 35 (67%) | 44 (83%) | 47 (72%) | 101 (78%) | .379 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 29±4.3 | 29±4.5 | 31.3±4.3 | 34±6 | <.01 |

| Risk factors for CVD | 35 (67%) | 34 (64) | 52(80%) | 102(78%) | .03 |

| Hypertension | 11 (21%) | 14 (26%) | 29 (45%) | 59 (45%) | <.01 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 2 (4%) | 6 (11%) | 11 (%17) | 35 (27%) | <.01 |

| Smoking | 29 (56%) | 29 (55%) | 26 (40%) | 61(47%) | .188 |

| CVD | 8 (15%) | 9 (17%) | 8 (12%) | 26 (%20) | .450 |

| Prehospital medications, n (%) | |||||

| Β blockers | 10 (19%) | 8 (15%) | 13 (20%) | 27 (21%) | .587 |

| ARBs/ACE inhibitors | 7 (13%) | 10 (19%) | 23 (35%) | 50 (38%) | <.01 |

| Calcium antagonists | 4 (7.6%) | 8 (15%) | 11 (17%) | 28 (%21) | .02 |

| Antiplatelet agents | |||||

| Laboratory findings | |||||

| Platelets (×103/μL) | 259±62 | 263±60 | 260±57 | 272±62 | .621 |

| Lymphocytes (×103/μL) | 2.6±0.6 | 2.5±0.8 | 2.6±0.7 | 2.7±0.6 | .701 |

| Neutrophil (×103/μL) | 4.47±1.2 | 4.6±1.4 | 4.6±1.5 | 4.7±1.4 | .730 |

| PLR | 102±28.5 | 108±42 | 105±36 | 105±31 | .857 |

| NLR | 1.9±1.03 | 2±1 | 1.8±1 | 1.8±0.7 | .183 |

| MPV, fL | 7.3±1.3 | 7.2±1 | 7.4±1 | 7.5±1.1 | .348 |

| RDW (%) | 15.2±1.02 | 15.6±1.06 | 15.7±1.2 | 16±1.2 | .04 |

BMI, Body Mass Index; CVD, Cardiovascular disease; ACE, angiotensin‐converting enzyme; ARB, Angiotensin receptor blocker; PLR, Platelet‐lymphocyte ratio; NLR, neutrophil‐lymphocyte ratio; MPV, mean platelet volume; fL, femtoliters; RDW, red cell distribution width.

Significant values are given in bold.

The polsomnographic study results are presented in Table 2. The distribution of sleep stages, AHI, mean and minimum oxygen saturation, ODI were significantly different among the groups (P<.01). All the patients had ESS score <10 and there was no significant difference among the groups with respect to ESS (P=.028).

Table 2.

Polysomnographic findings of the study group

| Group A control group (n=52) | Group B mild OSA (n=53) | Group C moderate OSA (n=65) | Group D severe OSA (n=130) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stage 1 (%) | 5.1±4.3 | 3.8±2.6 | 4.6±4.1 | 4.1±4.3 | .31 |

| Stage 2 (%) | 53±10 | 51±12.3 | 56±12 | 68±15 | <.01 |

| Stage 3 (%) | 24±8 | 26±10 | 24±10 | 17±12 | <.01 |

| REM (%) | 18±8 | 18.6±6 | 15.1±6.6 | 12±7 | <.01 |

| SE (%) | 83±13 | 85±12 | 84±11.8 | 85±13 | .353 |

| AHI events/h | 2.2±1.5 | 10.1±2.1 | 23±5.1 | 60±24 | <.01 |

| Mean O2 sat (%) | 110±117 | 92±4.1 | 90±3 | 86±6 | <.01 |

| Minimum O2 sat | 89±4.35 | 85±3 | 80±6.6 | 73±10 | <.01 |

| ODI | 2.06±1.5 | 9.5±3 | 21±5 | 57±23 | <.01 |

| ESS | 5 (0‐15) | 8 (0‐18) | 7 (0‐18) | 7 (0‐19) | .028 |

REM, Rapid eye movement; SE, Sleep efficiency; AHI, Apnea‐hypopnea index; sat, saturation; ODI, oxygen desaturation ındex; ESS, Epworth sleepiness scale.

Significant values are given in bold.

We also noted the correlations between polysomnographic results and laboratory parameters. Spearman correlation analysis showed a significant correlation only between RDW and polysomnographic parameters. The MPV, NLR and PLR were not significantly correlated with the polysomnographic parameters. RDW was positively correlated with the AHI and ODI but negatively correlated with the mean oxygen saturation (P<.05; Table 3).

Table 3.

Correlation between polysomnographic parameters and RDW

| RDW | ||

|---|---|---|

| r | P | |

| AHI events/h | .123 | .033 |

| Mean O2 sat (%) | −.118 | . 047 |

| ODI | .119 | .038 |

AHI, Apnea‐hypopnea index; sat, saturation; ODI, oxygen desaturation ındex.

Significant values are given in bold.

There were no significant differences in the platelet, lymphocyte, neutrophil counts; NLR; PLR; MPV and RDW between patients with OSA with vs without CVD (P>.05). RDW values were significantly higher in patients with than without CVD risk factors (P=.02).

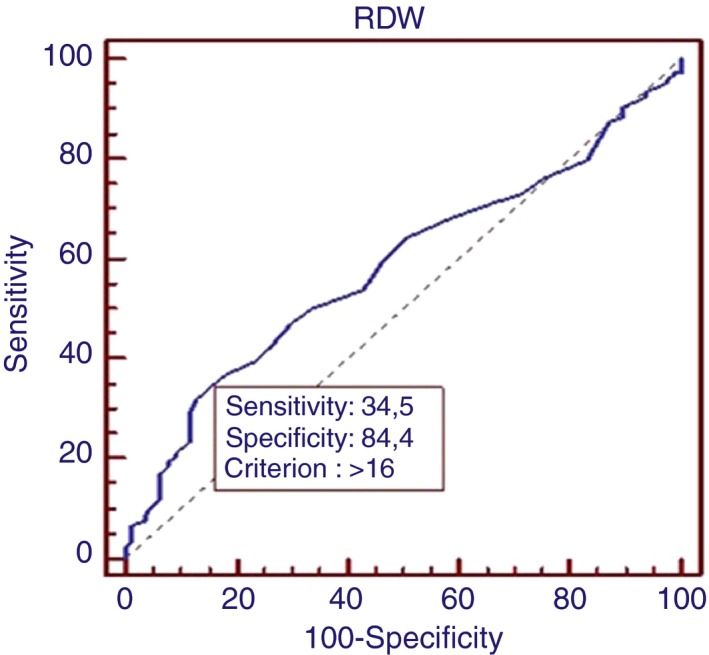

We used ROC analysis to determine the cut‐off value of RDW (>16) to demonstrate the presence of CVD risk factors. The analysis revealed a sensitivity of 34.5%, specificity of 84.4% and area under the ROC curve of 0.584. (CI=0.526‐0.640, P<.05; Figure 1).

Figure 1.

ROC analysis of RDW

4. Discussion

Ostructive sleep apnea has been associated with many comorbidities such as cardiovascular diseases, pulmonary diseases, endocrine dysfunctions and neuropsychiatric problems. Although the exact mechanism underlying these problems remains unclear, chronic inflammation has been implicated in their pathogenesis.15 To address this issue, we analyzed several inflammatory factors such as PLR, NLR, MPV, and RDW levels in patients with OSA. And also we evaluated the association of these markers with the severity of the disease and the presence of cardiovascular diseases in patients with OSA. Detection of inflammatory factors in OSA patients may help us to predict the risk and severity of these comorbid diseases.

Neutrophil‐ lymphocyte ratio is a new biomarker which indicates the presence of inflammation. Evaluation of the NLR in the diseases may help us to predict the progression and prognosis of the disease processes. Various studies have demonstrated the correlation between the NLR and lung cancer, pneumonia and tuberculosis.16, 17, 18 Gunay and associates indicated that NLR was higher in patients with acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) than in patients with stable COPD and healthy controls.19 However, in our study there was no significant difference among the OSA groups with respect to NLR. And also, NLR was not significantly correlated with polysomnographic parameters. This result is in agreement with Korkmaz and associates, who found no difference in NLR between patients with and without OSA.20

Platelet‐lymphocyte ratio, another recent novel biomarker, has been proved to be both sensitive and reliable for evaluation of inflammation. Sunbul and associates found that increased PLR was associated with non‐dipper state in hypertensive patients.21 Koseoglu and associates reported that PLR is strongly associated with the severity of OSA and CVD in patients with OSA.8 However, in our study, PLR was similar between the OSA and control groups. There was no significant difference in the PLR in patients with OSA with vs without CVD.

Chronic inflammation, hypoxia, and sympathetic overactivity are associated with the pathogenesis of platelet activation in OSA.5 MPV is another marker of platelet activation.22 Recent reports have demonstrated that MPV is significantly higher in patients with than without OSA.8, 23 The increased cardiovascular risk in patients with OSA may also be linked to abnormalities of coagulation and excessive platelet activation.24 In our study, we did not find any significant correlation between MPV and the severity of OSA. Our result is in agreement with that of Kurt and associates, who reported that the severity of OSA was not correlated with MPV.4

Inflammation has also the capacity to shorten red blood cell survival.25 Inflammation has been proposed as a key point in the association of RDW with the cardiovascular and pulmonary diseases.26 Ozsu and associates have demonstrated that OSA patients have elevated levels of RDW compared to controls but they did not find any association between the severity of OSA and RDW.27 However, in our study, RDW differed significantly among the OSA groups. Moreover, there was a significant correlation between the level of RDW and the severity of OSA. A high level of RDW in OSA may be caused by numerous factors including inflammation, age, and obesity. In addition, in our study, there was a positive correlation between the severity of OSA and age and BMI. And also, we found a significant positive correlation between the level of RDW and AHI and ODI. All these results suggest that RDW may play a role in the pathogenesis of OSA.

An elevated RDW may be an indicator of underlying inflammation in OSA. RDW can demonstrate the reverse consequences of OSA‐associated comorbidities, because vascular damage due to systemic inflammation is an important underlying mechanism in these diseases. Hypoxemia, inflammation, increased heart rate, and blood pressure in OSA lead to cardiovascular morbidity.28 We found that RDW values were significantly higher in patients with than without CVD risk factors. An elevated RDW may also be proposed as a simple and diagnostic tool for monitoring patients with OSA, those especially with cardiovascular disease. To address this issue, we determined the cut‐off value of RDW (>16) to demonstrate the presence of CVD risk factors.

Taken together, our results indicate that among these laboratory parameters, only RDW can be used as an inexpensive tool for triaging OSA patients for polysomnographic evaluation in sleep laboratories and these patients could able to reach earlier treatment options. And also, RDW might also be used as a marker of the response and patient compliance with continuous positive airway pressure treatment. However, there are some limitations of our study that have to be mentioned. We did not follow the patients prospectively and did not investigate the effect of continuous positive airway pressure treatment on RDW. In this context, prospective, randomized, controlled studies before and after continuous positive airway pressure treatment are needed to assess the association between these parameters and OSA.

Kıvanc T, Kulaksızoglu S, Lakadamyalı H, Eyuboglu F. Importance of laboratory parameters in patients with obstructive sleep apnea and their relationship with cardiovascular diseases. J Clin Lab Anal. 2018;32:e22199 10.1002/jcla.22199

References

- 1. Epstein LJ, Kristo D, Strollo PJ Jr, et al. Clinical guideline for the evaluation, management and long‐term care of obstructive sleep apnea in adults. J Clin Sleep Med. 2009;5:263‐276. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Fava C, Montagnana M, Favaloro EJ, Guidi GC, Lippi G. Obstructive sleep apnea syndrome and cardiovascular diseases. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2011;37:280‐297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Weiss JW, Launois SH, Anand A, Garpestad E. Cardiovascular morbidity in obstructive sleep apnea. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 1999;41:367‐376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kurt OK, Yildiz N. The importance of laboratory parameters in patients with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis. 2013;24:371‐374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ryan S, Taylor CT, McNicholas WT. Systemic inflammation.: a key factor in the pathogenesis of cardiovascular complications in obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome? Thorax. 2009;64:631‐636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Imhof BA, Aurrand‐Lions M. Angiogenesis and inflammation face off. Nat Med. 2006;12:171‐172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Horne BD, Anderson JL, John JM. Which white blood cell subtypes predict increased cardiovascular risk? J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;45:1638‐1643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Koseoglu HI, Altunkas F, Kanbay A, Doruk S, Etikan I, Demır O. Platelet‐lymphocyte ratio is an independent predictor for cardiovascular disease in obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2015;39:179‐185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cho KH, Jeong MH, Ahmed K, et al. Value of early risk stratification using hemoglobin level and neutrophil‐to lymphocyte ratio in patients with ST elevation myocardial infarction undergoing primary percutaneous coronary intervention. Am J Cardiol. 2011;107:849‐856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Conwell W, Lee‐Chiong T. Sleep apnea, chronic sleep restriction and inflammation. Perioperative implications. Sleep Med Clin. 2013;8:11‐21. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kanbay A, Tutar N, Kaya E, et al. Mean platelet volume in patients with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome and its relationship with cardiovascular diseases. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis. 2013;24:532‐536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Perlstein TS, Weuve J, Pfeffer MA, Beckman JA. Red blood cell distribution width and mortality risk in a community‐based prospective cohort. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169:588‐594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Flemons WW, Buysse AD, Redline S, et al. Sleep‐related breathing disorders in adults: recommendations for syndrome definition and measurement techniques in clinical research. The report of an American Academy of Sleep Medicine Task Force. Sleep. 1999;22:667‐689. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Johns MW. A new method for measuring daytime sleepiness: the Epworth sleepiness scale. Sleep. 1991;14:540‐545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Patel SR, Zhu X, Storfer‐Isser A, Jenny NS, Tracy R, Redline S. Sleep duration and biomarkers of inflammation. Sleep. 2009;32:200‐204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kemal Y, Yucel I, Ekiz K, et al. Elevated serum neutrophil to lymphocyte and platelet to lymphocyte ratios could be useful in lung cancer diagnosis. Asian Pac Cancer Prev. 2014;15:2651‐2654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Yoon NB, Son C, Um SJ. Role of the neutrophil‐lymphocyte count ratio in the differential diagnosis between pulmonary tuberculosis and bacterial community acquired pneumonia. Ann Lab Med. 2013;33:105‐110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Iliaz S, Iliaz R, Ortakoylu G, Bahadır A, Bagcı BA, Caglar E. Value of neutrophil/lymphocyte ratio in the differential diagnosis of sarcoidosis and tuberculosis. Annals of Thoracic Medicine. 2014;9:232‐235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Gunay E, Sarınc US, Akar O, Ahsen A, Gunay S, et al. Neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a retrospective study. Inflammation. 2014;37:374‐380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Korkmaz M, Korkmaz H, Kucuker F, Ayyıldız SN, Cankaya S. Evaluation of the association os sleep apnea‐related systemic inflammation with CRP, ESR and neutrophil‐to‐lymphocyte ratio. Med Sci Monit. 2015;21:477‐481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Sunbul M, Gerin F, Durmus E, et al. Neutrophil to lymphocyte and platelet to lymphocyte ratio in patients with dipper vs non‐dipper hypertension. Clin Exp Hypertens. 2014;36:217‐221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Smyth SS, McEver RP, Weyrich AS, et al. Platelet functions beyond hemostasis. J Thromb Haemost. 2009;7:1759‐1766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Varol E, Ozturk O, Gonca T, Has M, Ozaygın M. Mean platelet volume is increased in patients with severe obstructive sleep apnea. Scand J Clin Lab Invest. 2010;70:497‐502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Von Kanel R, Dimsdale JE. Hemostatic alterations in patients with obstructive sleep apnea and the implications for cardiovascular disease. Chest. 2003;124:1956‐1967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Weiss G, Goodnough LT. Anemia of chronic disease. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:1011‐1023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Wang F, Pan W, Pan S, Ge J, Wang S, Chen M. Red cell distribution width as a novel predictor of mortality in ICU patients. Ann Med. 2011;43:40‐46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ozsu S, Aybul Y, Gulsoy A, Bulbul Y, Yaman S, Ozlu T. Red cell distribution width in patients with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Lung. 2012;190:319‐326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Bradley TD, Floras JS. Obstructive sleep apnea and its cardiovascular consequences. Lancet. 2009;373:82‐93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]