Abstract

Purpose

Chronic Helicobacter pylori gastritis affects two‐thirds of the world's population and is one of the most common chronic inflammatory disorders of humans, the infection clearly results in chronic mucosal inflammation in the stomach and duodenum, which, in turn, might lead to abnormalities in gastroduodenal motility and sensitivity and is the most frequent cause of dyspepsia and peptic disease. Some studies showed that there was a correlation between low‐grade inflammation as CRP and HP infection. The purpose of this study was to investigate the relationship between the presence of HP infection and platelet/lymphocyte ratio (PLR).

Method

A total of 200 patients who met the HP criteria and 180 age‐ and gender‐matched control subjects were included in this randomized controlled trial. Patients were diagnosed to have HP according stomach biopsy and urea breath test, PLR was calculated from complete blood count at time of diagnosis and before initiating the treatment.

Results

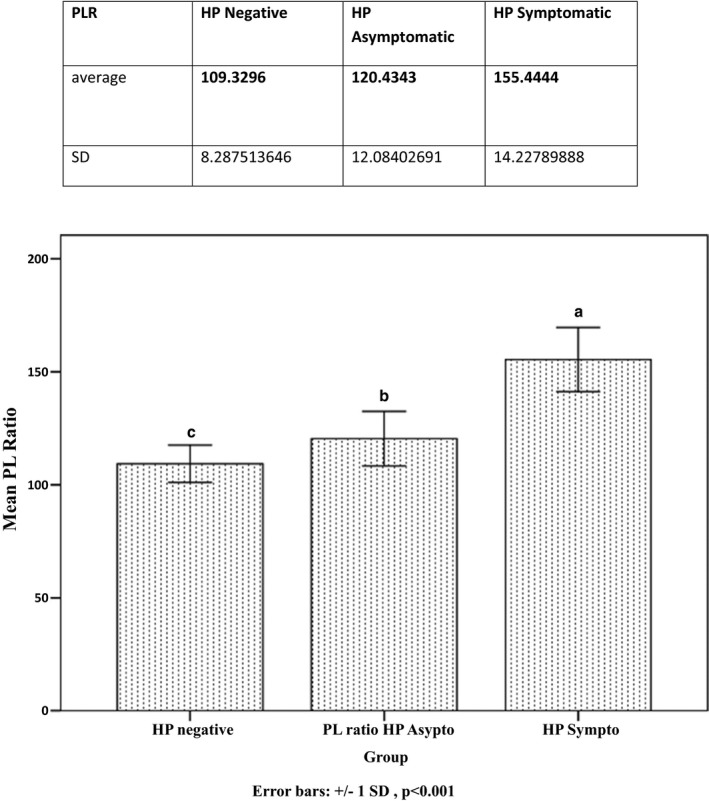

Patients with HP infection had significantly higher PLR compared to those without HP. Moreover, the patients with symptomatic HP had higher PLR than those with asymptomatic HP. While PLR increased as the severity of HP symptoms increased (r=.452, P<.001).

Conclusion

Our study indicated, for the first time, a significant association between HP infection and symptoms based on PLR, a simple and reliable indicator of inflammation. Furthermore, there an increase in PLR as the severity of HP increases.

Keywords: Helicobacter pylori, inflammation, peptic disease, platelet/lymphocyte ratio

1. Introduction

Helicobacter pylori is the most common chronic bacterial infection in humans.1, 2 Studies involving genetic sequence analysis suggest that humans have been infected with H. pylori since they first migrated from Africa around 58 000 years ago.3 H. pylori have been demonstrated worldwide and in individuals of all ages. H. pylori is a common cause of gastric and duodenal ulcers. Conservative estimates suggest that 50 percent of the world's population is affected. Infection is more frequent and acquired at an earlier age in developing countries compared with industrialized nations.2 Once acquired, infection persists and may or may not produce gastroduodenal disease. The route by which infection occurs remains unknown.1, 4 Person‐to‐person transmission of H. pylori through either fecal/oral or oral/oral exposure seems most likely.4, 5 Diagnostic testing for Helicobacter pylori can be divided into invasive and noninvasive techniques, based upon the need for endoscopy. Recommendations for diagnostic testing for H. pylori were first proposed by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) in 1994.6 More recent guidelines were published in 2006 by the European Helicobacter Study Group (EHSG)7 and in 2007 by the American College of Gastroenterology (ACG).8

Few studies showed that there was a correlation between inflammatory mediators and the presence of HP infection. Particularly, C‐reactive protein (CRP) levels were observed to increase in HP.9 Leukocyte activation occurs during an inflammatory reaction. Leukocytes were detected to have a role in several chronic diseases as diabetes, hypertension, atherogenesis, and thrombus formation and other inflammatory disorders. Along with high number of leukocytes, there is a significant relationship between neutrophil/lymphocyte ratio (NLR), PLR and severity and prognosis of CVD.10, 11 Our previous study demonstrated an association between NLR and HP12 but never were observed before an association between HP and PLR, this study was the first to detect a relationship between HP and PLR, another simple and reliable indicator of inflammation.

2. Patients and Methods

Two hundred patients, who had been diagnosed to have HP infection in the outpatient clinic according to established criteria for suspected HP infection, were recruited for the study. A total of 180 age‐ and gender‐matched healthy subjects were recruited as the control group. Patients with uncontrolled hypertension, uncontrolled diabetes, renal failure, hepatic failure, and/or manifest heart disease, such as cardiac failure, coronary arterial disease, arrhythmia, and cardiac valve disease, were excluded. Similarly, patients with infection, acute stress, chronic systemic inflammatory disease, upper or lower gastrointestinal bleeding, and those who had been receiving medications affecting the number of leukocytes were excluded, as well. All the participants included in the study were informed about the study, and their oral and written consents on participating voluntarily were obtained.

Helicobacter pylori was diagnosed according to the National Institutes of Health (NIH) in 1994.6 More recent guidelines were published in 2006 by the European Helicobacter Study Group (EHSG)7 and in 2007 by the American College of Gastroenterology (ACG).8

All patients were diagnosed as having HP infection according to the use of Urea breath testing (UBT) that is based upon the hydrolysis of urea by H. pylori to produce CO2 and ammonia using the non‐radioactive 13C test (Meretek, Otsuka Pharmaceuticals), A labeled carbon isotope is given by mouth; H. pylori liberate tagged CO2 that can be detected in breath samples with sensitivity and specificity are approximately 88%‐95% and 95%‐100% respectively. Gastric biopsies were performed to all patients in addition to urea breath test.

Patients were classified into two groups based on the clinical symptoms of HP: group 1 (patients with asymptomatic HP), group 2 (patients with symptomatic HP), and the control group.

Plasma glucose, urea, creatinine, total cholesterol, TG, HDL, and LDL levels were measured in the venous blood samples obtained in the morning after eight‐hour fasting. Complete blood count was studied in our hematology unit with Beckman‐Coulter Gen‐S system device (Beckman‐Coulter Inc., Fullerton, CA, USA).

2.1. Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were defined as mean±standard deviation, and categorical variables were given as percentages. Independent sample t test or Mann–Whitney U test were used for continuous variables, and chi‐square test for categorical variables. Statistical analyses were performed using Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) Version 15.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Any P value <.05 was considered as statistically significant.

3. Results

Totally, 200 patients with HP half of them symptomatic and 180 age‐ and gender‐matched subjects were included in the study as patient and control groups respectively. Clinical and vital signs characteristics of both groups are summarized in Table 1. As shown in Table 2, while numbers of white blood cells (WBC), neutrophils, platelet but not lymphocytes in the patients with HP were higher than those without HP, hemoglobin levels were comparable. Patients with HP had significantly higher PLR compared to those without HP. Furthermore, PLR increased more as severity of HP symptoms increased PLR was significantly higher in symptomatic HP group compared to asymptomatic group (P<.001) and control groups (P<.001); (PLR=155±14, 120±12, and 109±8, respectively, P<.001 for ANOVA) Figure 1. PLR was also significantly higher in patients with asymptomatic HP (n=100) compared to controls (n=180; 120±12 vs 109±8, P<.001). Using a cut‐off level of 140, PLR predicted severe symptoms with a sensitivity of 92% and specificity of 70% (area under ROC curve=0.645, 95% CI: 0.587‐0.703; P<.001 (Table 3).

Table 1.

Differences between various parameters of the groups with and without HP

| HP (−) | HP (+) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (y) | 49±11 | 50±10 | .440 |

| Gender (Male %) | 55 | 51 | .469 |

| SBP (mm Hg) | 132±17 | 134±16 | .079 |

| DBP (mm Hg) | 81±12 | 82±13 | .031 |

DBP, diastolic blood pressure; HP, Helicobacter pylori; SBP, systolic blood pressure.

Table 2.

Differences between the hematologic parameters of the groups with and without HP

| Control group | Asymptomatic HP | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 13.5±0.54 | 13.4±0.52 | .805 |

| Platelet count (×1000) | 250±54 | 260±72 | .212 |

| WBC | 8528±984 | 9930±1413 | <.001 |

| Neutrophil count | 6039±868 | 8205±1162 | <.001 |

| Lymphocyte count | 2313±577 | 2250±120 | <.001 |

| PLR | 108±0.23 | 115±0.63 | <.001 |

HP, Helicobacter pylori; PLR, platelet/lymphocyte ratio; WBC, white blood cells.

Figure 1.

Differences between all groups

Table 3.

Differences between the hematologic parameters of the groups with symptomatic vs asymptomatic HP

| Symptomatic HP | Asymptomatic HP | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 13.1±0.26 | 13.4±0.52 | .694 |

| Platelet count (×1000) | 288±54 | 260±72 | <.001 |

| WBC | 10 237±414 | 9930±1413 | <.001 |

| Neutrophil count | 9027±426 | 8205±1162 | <.001 |

| Lymphocyte count | 1850±124 | 2250±120 | <.001 |

| PLR | 155 ± 14 | 115±0.63 | <.001 |

HP, Helicobacter Pylori; PLR, platelet/lymphocyte ratio; WBC, white blood cells.

4. Discussion

The present study indicated, for the first time, a significant association between HP infection and inflammation on the basis of PLR, a simple and reliable indicator of inflammation. Furthermore, the link between the increases in the number of PLR associated HP infection has been reported, for the first time, to our knowledge. H. pylori have been demonstrated worldwide and in individuals of all ages. H. pylori is a common cause of gastric and duodenal ulcers. Conservative estimates suggest that 50% of the world's population is affected. Infection is more frequent and acquired at an earlier age in developing countries compared with industrialized nations.2 Once acquired, infection persists and may or may not produce gastroduodenal disease, but it is well‐established that H. pylori causes gastrointestinal disease. In fact, H. pylori cause more than 90% of duodenal ulcers and more than 80% of stomach ulcers.13 H. pylori also cause gastritis, an inflammation of the stomach lining, which can lead to chronic inflammation or loss of function of the cells (atrophic gastritis). Furthermore, individuals with this infection have a 2‐6‐fold increased risk of developing mucosa‐associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma and stomach cancer compared to uninfected individuals.14

Although H. pylori infect the stomach, it has been shown to play a role in the development of numerous non‐gastrointestinal diseases. Researchers suggest that H. pylori induces systemic inflammation as well as decreases the absorption of nutrients, thereby increasing the risk of several diseases. Some of the conditions associated with H. pylori infection include cardiovascular disease (CVD), stroke, anemia, glaucoma, Alzheimer's disease, rosacea, eczema, chronic hives, diabetes, thyroid disease, and idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura.15 Eradication treatment of H. pylori can improve numerous conditions, and natural strategies exist to help eradicate this harmful organism.

One study found that eradication treatment of H. pylori increased high‐density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol, and decreased the inflammatory markers C‐reactive protein (CRP) and fibrinogen, which are associated with atherosclerosis and cardiovascular disease risk.16 Research has shown that the presence of H. pylori antibodies were significantly more frequent in individuals with coronary artery disease (CAD) compared to healthy control subjects. In fact, the presence of antibodies was nearly double in the subjects with CAD compared to the control group, which also correlated with increased CRP levels.9 Similarly, another study showed that H. pylori infection was related to increased arterial stiffness and increased systolic blood pressure in diabetic subjects.17

Our study is the first to detect an association between HP and other available and simple inflammatory marker to control disease activity, differences between asymptomatic and symptomatic persons strengthen our decision to treat and eradicate the organism and maybe in the future to follow‐up after therapy. PLR infrequently practical, despite the simplicity of the test and availability that can be useful in various inflammatory diseases.

Previous studies showed that WBC, leukocyte subtype, and NLR were indicators of systemic inflammation.18 Number of neutrophils is considered to be associated with formation, complexity, and activation of atheromatous plaque.19 Consistent with the literature, the present study showed that the number of platelet increased in HP; moreover, the number of platelet increased as symptoms of HP increased. The variation in the increase rate of number of lymphocytes was insignificant between the HP subjects and those without HP. That was considered to be consistent with more increase in the number of platelet compared to that of lymphocytes and hence increase in PLR in the conditions associated with inflammation. In a previous study, NLR was shown to be a predictor in the progression of atherosclerosis.20, 21 The study by Horne and the colleagues found a significant association between the severity and prognosis of CVD, high WBC and NLR.10 Our previous study have demonstrated the usefulness of NLR in HP in small group of patients but we have not examined the utility of PLR.11 The present study showed that PLR was strongly correlated with the presence of HP and severity of symptoms of HP infection as NLR.

However, associations between PLR and HP have still yet to be investigated in more prospective studies with the correlation of NLR. PLR, a promising marker of inflammation starting to find a place in the literature, was found to be associated with the presence and the severity HP.

5. Conclusion

It is known that systemic inflammation is involved in various chronic diseases and sometime can be considered a major risk for development of CVD. The present study is the first report about the association of PLR with the presence of HP as chronic inflammatory disease as with NLR. The results may have clinical importance, because this marker indicating can be useful for detecting HP infection and severity, deciding about treatment time and follow‐up to ensure eradication of HP, otherwise continuing inflammation in HP may be the early markers of developing cardiovascular events, or even stomach malignancy.

5.1. Limitations

The most important limitation of the present study was the number of the patients included, in addition the absence of follow‐up period after treatment to check the response of therapy and variation of this marker and the correlation with NLR.

Ethics Approval

The study protocol was approved by signing an informed consent for blood sampling approved by the institutional committee in accordance with the Helsinki declaration.

Farah R, Hamza H, Khamisy‐farah R. A link between platelet to lymphocyte ratio and Helicobacter pylori infection. J Clin Lab Anal. 2018;32:e22222 10.1002/jcla.22222

References

- 1. Cave DR. Transmission and epidemiology of Helicobacter pylori . Am J Med. 1996;100:12S‐17S; discussion 17S–18S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Pounder RE, Ng D. The prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection in different countries. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1995;9(suppl 2):33‐39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Linz B, Balloux F, Moodley Y, et al. An African origin for the intimate association between humans and Helicobacter pylori . Nature. 2007;445:915‐918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Mégraud F. Transmission of Helicobacter pylori: faecal‐oral versus oral‐oral route. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1995;9(suppl 2):85‐91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Perry S, de la Luz Sanchez M, Yang S, et al. Gastroenteritis and transmission of Helicobacter pylori infection in households. Emerg Infect Dis. 2006;12:1701‐1708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. NIH Consensus Conference . Helicobacter pylori in peptic ulcer disease. NIH Consensus Development Panel on Helicobacter pylori in Peptic Ulcer Disease. JAMA. 1994;272:65‐69. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Malfertheiner P, Megraud F, O'Morain C, et al. Current concepts in the management of Helicobacter pylori infection: the Maastricht III Consensus Report. Gut. 2007;56:772‐781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Chey WD, Wong BC, Practice Parameters Committee of the American College of Gastroenterology . American College of Gastroenterology guideline on the management of Helicobacter pylori infection. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:1808‐1825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Jha HC, Prasad J, Mittal A. High immunoglobulin A seropositivity for combined Chlamydia pneumoniae, Helicobacter pylori infection, and high‐sensitivity C‐reactive protein in coronary artery disease patients in India can serve as atherosclerotic marker. Heart Vessels. 2008;23:390‐396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Horne BD, Anderson JL, John JM, et al. Which white blood subtypes predict increased cardiovascular risk? J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;45:1638‐1643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Zhou D, Fan Y, Wan Z, et al. Platelet‐to‐lymphocyte ratio improves the predictive power of GRACE risk score for long‐term cardiovascular events in patients with acute coronary syndrome. Cardiology. 2016;134:39‐46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Farah R, Khamisy‐Farah R. Association of neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio with presence and severity of gastritis due to Helicobacter pylori infection. J Clin Lab Anal. 2014;28:219‐223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) . Helicobacter pylori. http://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/aip/research/hp.html. Accessed January 15, 2017.

- 14. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) . Helicobacter pylori and peptic ulcer disease. http://www.cdc.gov/ulcer/keytocure.htm#illnesses. Accessed January 15, 2017.

- 15. Szlachcic A. The link between Helicobacter pylori infection and rosacea. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2002;16:328‐333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Pellicano R, Oliaro E, Fagoonee S, et al. Clinical and biochemical parameters related to cardiovascular disease after Helicobacter pylori eradication. Int Angiol. 2009;28:469‐473. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ohnishi M, Fukui M, Ishikawa T, et al. Helicobacter pylori infection and arterial stiffness in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Metabolism. 2008;57:1760‐1764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Papa A, Emdin M, Passino C, Michelassi C, Battaglia D, Cocci F. Predictive value of elevated neutrophil‐lymphocyte ratio on cardiac mortality in patients with stable coronary artery disease. Clin Chim Acta. 2008;395:27‐31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Avanzas P, Arroyo‐Espliguero R, Cosin‐Sales J, et al. Markers of inflammation and multiple complex stenosis (pancoronary plaque vulnerability) in patients with non‐ST segment elevation acute coronary syndromes. Heart. 2004;90:847‐852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kalay N, Dogdu O, Koc F, et al. Hematologic parameters and angiographic progression of coronary atherosclerosis. Angiology. 2012;63:213‐217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Pasceri V, Cammarota G, Patti G, et al. Association of virulent Helicobacter pylori strains with ischemic heart disease. Circulation. 1998;97:1675‐1679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]