Abstract

Background

The present study consisted of a total of 200 subjects (100 confirmed coronary artery disease (CAD) patients), both men and women, and 100 healthy control individuals.

Methods

Serum concentration of IL‐6 and RANTES were measured by enzyme‐linked immunosorbent assay kit. For SNPs analysis, sanger method of DNA sequencing was followed.

Results

We observed variable numbers of SNP sites at ‐174 G/C, ‐572 G/C, and ‐597 G/A in IL‐6 and ‐28 C/G and ‐109 C/T in RANTES promoters in CAD patients compared with control individuals. However, the observed changes in the number of SNPs were found to be non‐significant compared with control individuals. The IL‐6 level was found to be significantly (P<.001) elevated in CAD patients compared with control. Moreover, RANTES serum level did not show any significant change in CAD patients.

Conclusion

Based on our result, it is quite clear that inflammation has a role in the pathogenesis of CAD but does not lead to significant changes at the genetic level in our population. As far as our knowledge goes, this is the first report that shows the genetic diversity in IL‐6 and RANTES promoters and their respective levels in Saudi CAD patients.

Keywords: coronary artery disease, ELISA, IL‐6, polymorphism, RANTES

1. Introduction

Atherosclerosis is a fatal, complex, and multifactorial condition and is considered as the primary cause of coronary artery disease (CAD), stroke, and peripheral vascular disease.1, 2 Even though all the pathogenic components associated with atherogenesis have not been completely elucidated, oxidative stress and inflammation have been suggested as a significant triggering factor.3, 4, 5 The chronic inflammatory process arbitrated by several pro‐inflammatory mediators produces different pathological events during various stages of the disease, which could ultimately lead to myocardial infarction (MI), stroke, and sudden death.6 Moreover, dysfunctional endothelium, smooth muscle cells, lipid‐laden macrophages, and T lymphocytes have also been proposed as the lethal contributors of atherosclerotic plaque formation.2, 7 Moreover, inflammatory mediators are also suggested to be involved in the plaque destabilization process along with other mechanisms. These inflammatory responses are part of the pathological remodeling process, which results as one of the fatal outcomes in the form of MI.2

Among the group of inflammatory mediators, IL‐6 is the principal cause of disturbed vascular biology and the most important culprit of future MI adverse events.8 Atherosclerotic lesions are the important site of IL‐6 release and its increased level has been associated with acute ischemic conditions and recurrent events in CAD patients.9, 10 Moreover, the elevated IL‐6 level has also been suggested as the major determinant of the acute phase condition and associated inflammatory injury.9 The regulated upon activation, normal T cell expressed and secreted (RANTES) is the C‐C chemokine that regulates leukocyte trafficking and is also associated with inflammatory events in response to coronary artery lesions.11 It is an important chemokine, secreted from the alpha granules of adhering platelets. Their binding with specific receptors (CCR1 and CCR5) had been suggested as a crucial causative of atherosclerosis in the scientific literature.12

Genetic association of IL‐6 and RANTES and their possible role in the development of CAD had been reported in different ethnic populations.10, 13, 14, 15, 16 However, single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) hotspots in these genes are not reported to be consistent among the population of different racial and ethnic origins.10 The various stress conditions, geographical difference, racial and ethnic diversity are believed to be the reason behind these observed differences. Genetic polymorphisms in IL‐6 gene promoters at ‐174 G/C, ‐572 G/C, and ‐597 G/A positions have been reported in CAD patients of different ethnic populations.15, 17, 18 Moreover, SNP in RANTES promoter at ‐28 C/G and ‐109 C/T region has been reported in the literature.19, 20

Based on the above mentioned scientific reports of different SNP sites in different ethnic population, in the current study, we sequenced promoter region up to the sites where the SNP hotspots are reported in other populations. The purpose of the current study was to find out the possible polymorphic site at the promoter region (‐174, ‐572, and ‐597 in IL‐6 gene, and ‐28 and ‐109 in RANTES gene) and their association with serum level in the Saudi CAD patients. We believe that our case–control study could reveal the pathological linkage between the inflammatory regulations of CAD at the genetic level. To the extent our insight goes from the accessible literature, we are for the first time reporting SNPs in IL‐6 and RANTES promoters and their association with serum level in a single article especially in the Saudi population.

2. Materials and Methods

One hundred confirmed CAD patients visited at the cardiology department of King Abdulaziz University Hospital (KAUH), Jeddah and 100 healthy control individuals were included in the present study. The study was conducted during April 2014 to December 2015 after the approval from ethical committee of the institution. Written and properly informed consent was obtained from all the included participants before the beginning of the study. The selection of CAD patients was made after the diagnosis by coronary angiography and other routinely used biological parameters. Individuals who have a history of significant or serious uncontrolled disease, recent inflammatory events, unwilling, or unable to comply with the protocol were excluded from the study.

2.1. Sample collection

The peripheral blood samples were collected in EDTA and EDTA‐free tubes from selected cardiovascular patients and healthy control individuals. Serum separation was done by centrifugation at 2000 g for 5 minutes. The collected serum samples were stored at −80°C until further analysis.

2.2. Estimation of fasting glucose, HbA1c, and lipid profile

Serum HbA1c was analyzed on Dimension Vista™ System (Siemens Healthcare Diagnostics, Camberley, UK). The protocol provided by the manufacturer's was strictly adhered. Serum CRP, fasting glucose, and lipid profile were evaluated on a devoted Selectra ProM clinical chemistry analyzer system (ELITech, Sees, France). Non‐HDL cholesterol determinations were done by subtracting LDL value from total cholesterol.

2.3. Analysis of IL‐6 and RANTES serum levels

Estimation of IL‐6 and RANTES serum levels were done by using commercially available ELISA kits (Abcam, Shanghai, China). The instructions provided by the manufacturer were strictly adhered.

2.4. Genomic DNA extraction

Genomic DNA was extracted from 200 μL of whole blood using DNA purification kit (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) strictly adhering to manufacturer's instructions. Agarose gel electrophoresis was performed to examine the integrity of genomic DNA.

2.5. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR)

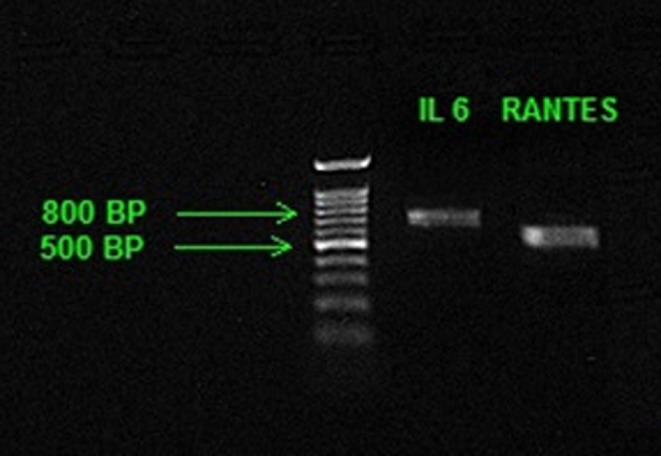

Extracted DNA samples were genotyped for IL‐6 and RANTES promoters using conventional PCR method with specifically designed primers (Table 1). Briefly, l μL of 10 pmol/L forward and reverse primers were added to the reaction mixture containing 12.5 μL of DNA polymerase (AmpliTaq Gold 360; Applied Biosystems, Foster city, CA, USA) and 2 μL of genomic DNA. Total reaction volume was made up to 25 μL with the help of nuclease‐free water. The PCR was performed on Veriti 96‐well thermal cycler (Applied Biosystems). The 35 cycles PCR program was set up for IL‐6 with a 10‐minute initial denaturation at 95°C along with 30 seconds of denaturation at 95°C. The annealing temperature of 58°C was kept for 30 seconds followed by an extension for 60 seconds at 72°C. The final extension time was kept for 7 minutes at 72°C and products were stored at 4°C till next procedure. Similarly, the 35 cycles of the PCR program was also made for RANTES with the only difference of annealing temperature at 60°C. The PCR product of 739 bp and 585 bp were received for IL‐6 and RANTES, respectively. The integrity and molecular weight of the amplified region were confirmed using agarose gel electrophoresis (Figure 1).

Table 1.

PCR primers sequence for IL‐6 and RANTES gene promoter region

| Gene | Primer sequence |

|---|---|

| IL‐6 | Forward 5′ ACCTGGAGACGCCTTGAAGTAACT 3′ |

| Reverse 5′ TAAGGATTTCCTGCACTTACTTGTG 3′ | |

| RANTES | Forward 5′ AGAGACAGAGACTCGAAT 3′ |

| Reverse 5′ CAGTAGCAATGAGGATGACAGCGA 3′ |

Figure 1.

A representative of 1% agarose gel photograph of IL‐6 and RANTES promoters. Lane A: DNA marker; Lane B PCR product of IL‐6 promoter; Lane C: PCR product of RANTES promoter

2.6. PCR products purification, cycle sequencing, and DNA sequencing

The purification of PCR products was done using PCR purification kit (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), which enables the removal of excess salts, primers, and dNTPs. Purified PCR products of IL‐6 and RANTES promoter region were used to perform cycle sequencing as per the BigDye terminator v1.1 cycle sequencing protocol. Cycle sequencing was performed for 25 cycles with an initial denaturation for 5 minutes at 96°C followed by denaturation for 10 seconds at 96°C, annealing for 5 seconds at 55°C and extension for 4 minutes at 60°C. Subsequent purification of cycle sequencing products was done using Big Dye XTerminator cycle sequencing kit (Applied Biosystems), strictly adhering manufacture instructions. The DNA sequencing was done using sanger sequencing method with the application of capillary electrophoresis on 3500xL genetic analyzer (Applied Biosystems) by POP‐7TM polymer. Sequenced data with chromatograms were viewed and imported using sequencer analysis software version 5.4.

2.7. Sequence analysis

Trace files obtained from sanger sequencing were subjected to base and quality calling using Tracetuner V3.0.6.21 Tracetuner was used to call base with the “‐het” parameter and low‐quality regions in the sequences were determined using optimized parameters “‐trim_window” and “‐trim_threshold”. Fasta and quality files generated from each trace file were further converted to Fastq format and low‐quality ends were trimmed using in‐house developed Perl script. We purposely took the stringent parameter for low‐quality trimming as we were dealing with only forward sequences for each amplicon. Fastq sequences of each sample were further aligned to reference sequences using Saha2.22 Alignments were further manually checked using Tablet V.23 Alignments were converted to pileup format using Samtools.24 Genotype for each sample was called with the help of in‐house‐developed Perl scripts. In the case of conflict at any locus between two sequences of the same sample, the type was judiciously called considering the mapping quality and base quality at the locus. The whole above mentioned process, that is, base calling to genotype calling were iterated for each gene.

2.8. Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed by GraphPad Instat 3.05 (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). Basic and clinical variables like age, BMI, lipids, glucose, serum IL‐6, RANTES, and hs‐CRP of the study population are mentioned as mean±SD. Comparison of these variables between patients and control individual was carried out by chi‐square and two‐tailed t‐test. The genotype at ‐174 G/C, ‐572 G/C, ‐597 G/A in IL‐6 promoter and ‐28 C/G and ‐109 C/T in RANTES promoter, as well as allele frequencies, were measured by the chi‐square test. A significant probability (P<.05) was considered as a significant criterion.

3. Results

The study population consists of 100 angiographically confirmed CAD patients [62 men and 38 women] and 100 healthy control individuals [58 men and 42 women]. The baseline demographic characteristics of both groups are presented in Table 2. A statistical correlation has been evaluated for different risk factors viz. age, sex, BMI, hypertension, smoking, and status of physical activities between CAD patients and control individuals. All the above‐mentioned risk factors such as age (P<.001), sex (P<.05), BMI (P<.01), hypertension (P<.001), smoking (P<.01), and physical activity (P<.05) were found to be significantly associated with CAD patients. Among the other CAD risk factors viz. total cholesterol and low‐density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol showed an increase in the level from 3.77 to 4.07 (P<.05) and 2.37 to 2.60 (P<.05), respectively. However, the triglycerides and high‐density lipoprotein (HDL) level did not show any significant change in their respective values. The markers of diabetic incidence also showed a remarkable rise in CAD patients, as fasting glucose and Hb1Ac level were found to be increased from 5.2 to 8.9 (P<.001) and from 5.2 to 8.15 (P<.001) respectively. Among the inflammatory markers, a significant increase in CRP and IL‐6 levels were recorded. The rise from 2.55 to 9.23 (P<.001) and 5.78 to 7.01 (P<.001) were recorded in CRP and IL‐6 levels, respectively. However, RANTES level did not show any significant change in CAD patients compared with control individuals (Table 2).

Table 2.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of study population

| Parameter | Control individuals (n=100) | CAD patients (n=100) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yr) | 47.7±5.06 | 60.6±8.85 | <.001 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 30.89±2.90 | 28.69±4.34 | <.01 |

| Male (n) | 58 | 62 | <.05 |

| Physical activity (n) | 56 | 34 | <.05 |

| Smokers (n) | 23 | 40 | <.01 |

| Hypertension (n) | 18 | 64 | <.001 |

| Fasting glucose (mmol/L) | 5.2±0.43 | 8.9±3.2 | <.001 |

| HbA1c (%) | 5.2±0.40 | 8.15±1.71 | <.001 |

| Total Cholesterol (mmol/L) | 3.77±0.56 | 4.07±0.93 | <.05 |

| Triglycerides (mmol/L) | 1.59±0.31 | 1.78±0.67 | NS |

| LDL cholesterol (mmol/L) | 2.37±0.56 | 2.60±0.93 | <.05 |

| HDL cholesterol (mmol/L) | 1.04±0.16 | 1.15±0.31 | NS |

| CRP (mg/L) | 2.55±0.33 | 9.23±3.56 | <.001 |

| Serum IL‐6 (pg/mL) | 5.78±1.56 | 7.01±2.72 | <.001 |

| Serum RANTES (pg/mL) | 1024.98±188.97 | 998.06±358.53 | NS |

DNA sequencing was carried out to sequence 700‐bp upstream of IL‐6 genes to capture the variant exist in the promoter region. In fact, two pairs of primers were used to amplify the promoter region of IL‐6 gene in control samples, but we sequence only the forward amplicons. We amplified three pairs of primer in CAD samples to confidently cover each base of the targeted promoter region. We successfully obtained 180 trace files from 90 control samples (two files for each sample) and 262 trace file from 93 CAD samples. Most of the CAD samples were covered with three sequenced amplicons. However, there were four samples which were covered with only one trace file each, whereas 17 samples were covered with two trace files. Some amplicons in eight samples were also repeated. Finally, we obtained high‐quality sequenced data of 202553 bp from 432 sequences representing all the samples (CAD and control). Moreover, 10 trace files were completely rejected as the base called with very poor quality and could not qualify minimum quality criteria. Average sequence length was found to be ~469 bp, whereas shortest and the longest sequence was noted as 79 bp and 879 bp, respectively. We were interested in already reported loci at ‐597 A/G (rs1800797), ‐572 G/C (rs1800796), and ‐174 G/C (rs1800795) in IL‐6 promoter.

Locus ‐174 G/C (rs1800795) was found to be covered in 90 CAD and 89 control samples (Table 3). This locus showed polymorphism but non‐significant allelic and genotypic association was observed. Genotype CC was found to be rare in both control and CAD group (3.37% and 3.33%, respectively) while GC was accounted for 27.77% and 25.84% samples, respectively, in diseased and control individuals. In fact, the individuals with GG genotype were found to be major in the Saudi population. Moreover, carriage rate of A and G allele was also found to be non‐significantly associated with control and CAD patients. Similarly, ‐572 G/C (rs1800796) locus was covered in 84 CAD and 75 control samples. At this region also, a non‐significant genotypic and allelic association was observed. GG was recorded as the major genotype and heterozygous condition was observed in 26% and 28% in CAD and control individuals, respectively. CC genotype was found to be rare, and not observed in the control group (Table 3). The third locus of interest was ‐597 A/G (rs1800797). This locus was also genotyped in 84 CAD and 75 control individuals. The study population was found to be prevalent with only AA genotype with the only exception of GG genotype in one individual of the control group (Table 3). This locus also did not show any significant polymorphism between CAD and control individuals.

Table 3.

Distribution of Genotype, allele frequencies and carriage rates of IL6 ‐597 A/G, ‐572 G/C, and ‐174 G/C polymorphism among control and CAD patients

| IL‐6‐597 A/G | IL6‐572 G/C | IL6‐174 G/C | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genotype frequency | ||||||||

| Control Counts (%) (n=75) | CAD Counts (%) (n=84) | Control Counts (%) (n=75) | CAD Counts (%) (n=84) | Control Counts (%) (n=89) | CAD Counts (%) (n=90) | |||

| AA | 74 (98.66) | 84 (100) | GG | 54 (72.00) | 59 (70.23) | GG | 63 (70.78) | 62 (68.88) |

| AG | GC | 21 (28.00) | 22 (26.19) | GC | 23 (25.84) | 25 (27.77) | ||

| GG | 1 (1.33) | CC | 3 (3.57) | CC | 3 (3.37) | 3 (3.33) | ||

| P value | .56 | .25 | .95 | |||||

| Allele frequencies | ||||||||

| A | 148 (98.66) | 168 (100) | G | 129 (86.00) | 140 (83.33) | G | 149 (83.70) | 149 (82.77) |

| G | 2 (1.33) | 0 | C | 21 (14.00) | 28 (16.66) | C | 29 (16.29) | 31 (17.22) |

| P value | .13 | .51 | .81 | |||||

| Carriage rates | ||||||||

| A(+) | 74 (98.66) | 84 (100) | G (+) | 75 (100) | 81 (96.42) | G (+) | 86 (96.62) | 87 (96.66) |

| A(−) | 1 (1.33) | G (−) | 0 | 3 (3.57) | G (−) | 3 (3.37) | 3 (3.33) | |

| P value | .28 | .09 | 1 | |||||

| G(+) | 1 (1.33) | C (+) | 21 (28.00) | 25 (29.76) | C (+) | 26 (29.21) | 28 (31.11) | |

| G(−) | 74 (98.66) | 84 (100) | C (−) | 54 (72.00) | 59 (70.23) | C (−) | 63 (70.78) | 62 (68.88) |

| P value | .28 | .8 | .78 | |||||

The RANTES promoter region was targeted with two pairs of primers in 183 samples. Only the forward amplicons were subjected to be sequenced through sanger method. We successfully obtained 163 trace files from 81 control samples and 210 trace files from 102 CAD samples. The six amplicons from three samples were repeated in CAD samples and one amplicon was repeated in control sample. After processing, we obtained high‐quality sequenced data of 158290 bp from 368 sequences. Only three trace file were completely rejected due to low‐quality trimming. Out of these, high‐quality filtered sequences were found to be long and ~95% sequences were found to be of more than 400 bp. Average sequence length was found to be 430 bp, whereas the longest sequence was of 459 bp. Therefore, coverage across the promoter region was nearly uniform. The locus of interest in RANTES promoter was ‐28 C/G (rs2280788) and ‐109 C/T.

The RANTES ‐28 C/G (rs2280788) loci were typed in 81 healthy control individual and 102 CAD patients. The study population was prevalent with CC genotype only. Heterozygous genotype was completely absent in CAD group. However, two individual were found to be heterozygous in control individuals. Minor alleles were also completely absent in this studied population. Hence, no polymorphism (homozygous) was observed at all on this locus in the entire studied population (Table 4). Based on this result, it quite clear that the locus of intention, that is, rs2280788 cannot be the cause of any disease exist in our population. Similar result was also observed on another locus ‐109 C/T, where CC genotype was present across the groups (Table 4). Alternate genotype CC and TC were found to be rare in the genotyped population.

Table 4.

Distribution of Genotype, allele frequencies, and carriage rates of RANTES ‐28 C/G and ‐109 T/C polymorphism among control and CAD patients

| RANTES ‐28 C/G | RANTES ‐109 T/C | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genotype frequency | |||||

| Control Counts (%) (n=81) | CAD Counts (%) (n=102) | Control Counts (%) (n=81) | CAD Counts (%) (n=102) | ||

| CC | 79 (97.53) | 102 (100) | TT | 80 (98.76) | 100 (98.03) |

| CG | 2 (2.46) | 0 | TC | 1 (1.23) | 1 (0.98) |

| GG | CC | 1 (0.98) | |||

| P value | .27 | .66 | |||

| Allele frequencies | |||||

| C | 160 (98.76) | 204 (100) | T | 161 (99.38) | 201 (98.52) |

| G | 2 (1.23) | C | 1 (0.61) | 3 (1.47) | |

| P value | .11 | .43 | |||

| Carriage rates | |||||

| C(+) | 81 (100) | 102 (100) | T (+) | 81 (100) | 101 (99.01) |

| C(−) | 0 | T (−) | 0 | 1 (0.98) | |

| P value | 1 | .37 | |||

| G(+) | 2 (2.46) | 0 | C (+) | 1 (1.23) | 2 (1.96) |

| G(−) | 79 (97.53) | 102 (100) | C (−) | 80 (98.76) | 100 (98.03) |

| P value | .11 | .7 | |||

4. Discussion

Growing evidence indicates that CAD epidemic had been attributed to different pathogenetic processes such as oxidative stress and vascular inflammation.5, 25, 26 The vascular inflammatory response reflects as the foremost causative of CAD because its pathogenicity has been reported in all the stages of atherosclerosis viz. initiation, progression, and plaque rupture.27

The present study was designed to divulge the presence of SNP hotspots, in immunologically significant IL‐6 and RANTES genes in Saudi CAD population. IL‐6 is an important systemic inflammatory mediator and its role in crucial inflammatory events such as leukocyte recruitment and modulation of coagulation cascade are well documented.28 Several studies confirmed the role of IL‐6 in the linkage of systemic inflammation and cardiovascular disease.9, 29, 30 The clinical significance of IL‐6 extends from predicting future coronary artery events to worse in‐hospital outcome with unstable angina [UA].29 A significant increase in serum IL‐6 level was recorded in CAD patients compared with control individuals in our study (Table 2). The rise in IL‐6 levels could be due to the development and instability of atherosclerotic plaques by means of activation of leukocytes and endothelial cells or by the induction of different cytokines.31 Our study is in concurrent with earlier studies which also reported an increase in IL‐6 serum level in CAD patients.9, 32, 33

RANTES has been also reported as a significant contributor of inflammatory events associated with CAD. Its potential role in cell adhesion and signaling interactions to promote leukocyte recruitment has been reported in scientific literature.11, 34 Moreover, increased expression of RANTES has been also noted in different immune cells in response to atherosclerosis.35 A non‐definitive association between serum RANTES level and cardiovascular outcomes are reported earlier.36 A reduced level of RANTES has been suggested with a higher 2‐year cardiac mortality in male patients undergoing coronary angiography.37 The elevated RANTES levels are also reported as a predictive future cardiovascular event in patients with UA.38 Based on the non‐significant change in RANTES level, one study also reported their non‐predictive value in cardiovascular events in patients with acute coronary syndrome.39 Any significant change in RANTES level in CAD patients compared with control individuals was also not noticed by us (Table 2). It is widely known that the expression of chemokines and their cellular receptors are dependent on several biological events and may or may not influence susceptibility to inflammatory diseases including CAD. However, the expression of RANTES is highly dependent upon its receptor bioactivity as well as the cellular process such as leukocyte trafficking and activation.20 Our prospective case–control study extends the current literature as it represents a different, population‐based study to describe the relationship between systemic RANTES concentrations and CAD.

Genetic studies highlight possible the association of heritable elements with CAD pathogenicity.40, 41 The genetic variations in CAD‐related genes are important especially for those gene products that play an important role in cardiovascular physiology and has potential to discover completely new molecular mechanisms that predispose CAD.42 Although the exact mechanism of genetic association of CAD has not been completely elucidated, transcriptional regulation of IL‐6, and RANTES gene have been proposed as an important mechanism of CAD pathophysiology.43 There are also conflicting reports, which do not suggest the association of SNPs in human IL‐6 and RANTES promoters with different pathological condition of CAD in various ethnic population.15, 19, 20, 44 To the best of our knowledge, the present study reports the status of SNPs in IL‐6 and RANTES promoter region in Saudi CAD patients for the first time.

Our study did not observe any significant changes at previously reported SNP hotspots viz. ‐597 A/G (rs1800797), ‐572 G/C (rs1800796), and ‐174 G/C (rs1800795) in IL‐6 promoter. Similar results have been also reported in other ethnic population.20, 44, 45, 46 Our study further supports previous findings in different populations. However, the positive association of one or more sites of IL‐6 promoter gene has been also reported in some earlier findings in different populations.10, 15, 18 The polymorphism at ‐174 G/C promoter region and its association with the incidence of cardiovascular events has been reported in the German population.47 Jia et al. (48) reported that the SNP at ‐597 G/A in IL‐6 is not associated with the susceptibility to CAD in Han Chinese population.48 Our results also agree with their findings. Moreover, the same research group reported pathogenesis and progression of CAD at ‐572 G/C site in the same population.14 Recently, Saxena et al.49 reported ‐174 G/C (rs1800795) and ‐597 G/A (rs1800797) promoter polymorphisms in IL‐6 gene in type 2 diabetes patients more often co‐existed with CAD in Indian population.

A study on behalf of West of Scotland Coronary Prevention (WOSCOPS) reported that 174 G/C polymorphism in IL‐6 promoter is associated with the risk of coronary heart disease.18 Moreover, Satti et al.10 reported the increase in IL‐6 expression and ‐174 G/C polymorphism in IL‐6 promoter in the CAD patients in Pakistani population. One study by Brull et al.17 reported that both ‐174 G/C and ‐572 G/C polymorphisms in IL‐6 promoter could genetically influence interleukin response of this interleukin to the inflammatory stimulus after coronary artery bypass grafting. This group did not observe statistically significant association at ‐597 G/A site. Jang et al.15 reported a significant association of ‐572 G/C polymorphism with inflammatory variables in Korean CAD patients. Their study did not show any significant association with inflammatory variables and ‐174 G/C polymorphism. Based on the above scientific reports and our results, it is quite clear that there are discrepancies in the reports associated with the promoter polymorphism in IL‐6 gene and its association with CAD pathophysiology. These differences could be because of different demographic and ethnic origins of these studies.

Single nucleotide polymorphism in RANTES promoter has been considered as an important mutation associated with various health issues. An earlier study did not show the potential association of ‐28 C/G polymorphism with CAD in RANTES promoter gene. Vogiatzi et al.20 reported the non‐significant association of ‐28 C/G and ‐109 C/T RANTES mutations with susceptibility to CAD and restenosis after percutaneous coronary intervention. The genotype and allele frequencies of RANTES at ‐28 C/G were also reported as non‐significant between controls and CAD patients in Korean population.15 We also did not observe any significant association between RANTES/CCL5 gene variants at ‐28 C/G and ‐109 C/T in our studied population. Ethnic diversity could be the major possible reason behind the expression of genetic differences with variable phenotypes.50 Earlier studies on particular candidate loci and phenotypes have identified genes that show population differences due to pathogens, diet, climate adaptation and a large portion of which have outcomes for disease susceptibility.51 We believe that ours is a reproducible finding, not the result of genotyping error, and suggests larger sample size before a definite negative association is determined.

5. Conclusion

This study envisages genetic association of IL‐6 and RANTES promoters with Saudi CAD patients. We also report a significant rise in IL‐6 level in CAD patients compared with control individuals. However, the interpretation of our data should consider lower population size taken by us. Despite the limitations of our study, our results can possibly be utilized as a part of pharmaco‐genomic way to deal with tailor treatment regimens to individual patients in the light of their genetic susceptibility patterns.

Acknowledgments

This project was funded by the National Plan for Science Technology and Innovation (MAARIFAH)—King Abdulaziz City for Science and Technology—the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia—award number (11‐BIO‐2020‐03). The authors also acknowledge with thanks Science and Technology Unit, King Abdulaziz University for technical support.

References

- 1. Firoz CK, Jabir NR, Kamal MA, et al. Neopterin: an immune biomarker of coronary artery disease and its association with other CAD markers. IUBMB Life. 2015;67:453–459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Jabir NR, Tabrez S. Cardiovascular disease management through restrained inflammatory responses. Curr Pharm Des. 2016;22:940–946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Jabir NR, Siddiqui AN, Firoz CK, et al. Current updates on therapeutic advances in the management of cardiovascular diseases. Curr Pharm Des. 2016;22:566–571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Jonasson T, Ohlin A‐K, Gottsäter A, Hultberg B, Ohlin H. Plasma homocysteine and markers for oxidative stress and inflammation in patients with coronary artery disease–a prospective randomized study of vitamin supplementation. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2005;43:628–634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bonomini F, Tengattini S, Fabiano A, Bianchi R, Rezzani R. Atherosclerosis and oxidative stress. Histol Histopathol. 2008;23:381–390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Firoz CK, Jabir NR, Khan MS, et al. An overview on the correlation of neurological disorders with cardiovascular disease. Saudi J Biol Sci. 2015;22:19–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ghattas A, Griffiths HR, Devitt A, Lip GYH, Shantsila E. Monocytes in coronary artery disease and atherosclerosis: where are we now? J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62:1541–1551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Zakynthinos E, Pappa N. Inflammatory biomarkers in coronary artery disease. J Cardiol. 2009;53:317–333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Su D, Li Z, Li X, et al. Association between serum interleukin‐6 concentration and mortality in patients with coronary artery disease. Mediators Inflamm. 2013;2013:726178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Satti HS, Hussain S, Javed Q. Association of interleukin‐6 gene promoter polymorphism with coronary artery disease in Pakistani families. Scientific World J. 2013;2013:538365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Simeoni E, Winkelmann BR, Hoffmann MM, et al. Association of RANTES G‐403A gene polymorphism with increased risk of coronary arteriosclerosis. Eur Heart J. 2004;25:1438–1446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Böger CA, Fischereder M, Deinzer M, et al. RANTES gene polymorphisms predict all‐cause and cardiac mortality in type 2 diabetes mellitus hemodialysis patients. Atherosclerosis. 2005;183:121–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Humphries SE, Luong LA, Ogg MS, Hawe E, Miller GJ. The interleukin‐6 ‐174 G/C promoter polymorphism is associated with risk of coronary heart disease and systolic blood pressure in healthy men. Eur Heart J. 2001;22:2243–2252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Jia X, Tian Y, Wang Y, et al. Association between the interleukin‐6 gene ‐572G/C and ‐597G/A polymorphisms and coronary heart disease in the Han Chinese. Med Sci Monit. 2010;16:CR103–CR108. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Jang Y, Kim OY, Hyun YJ, et al. Interleukin‐6‐572C>G polymorphism‐association with inflammatory variables in Korean men with coronary artery disease. J Lab Clin Med. 2008;151:154–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ting K‐H, Ueng K‐C, Chiang W‐L, et al. Relationship of genetic polymorphisms of the chemokine, CCL5, and its receptor, CCR5, with coronary artery disease in Taiwan. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2015;2015:e851683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Brull DJ, Montgomery HE, Sanders J, et al. Interleukin‐6 gene ‐174 g>c and ‐572 g>c promoter polymorphisms are strong predictors of plasma interleukin‐6 levels after coronary artery bypass surgery. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2001;21:1458–1463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Basso F, Lowe GDO, Rumley A, McMahon AD, Humphries SE. Interleukin‐6 ‐174G>C polymorphism and risk of coronary heart disease in West of Scotland coronary prevention study (WOSCOPS). Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2002;22:599–604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Al‐Qahtani A, Alarifi S, Al‐Okail M, et al. RANTES gene polymorphisms (‐403G>A and ‐28C>G) associated with hepatitis B virus infection in a Saudi population. Genet Mol Res. 2012;11:855–862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Vogiatzi K, Voudris V, Apostolakis S, et al. Genetic diversity of RANTES gene promoter and susceptibility to coronary artery disease and restenosis after percutaneous coronary intervention. Thromb Res. 2009;124:84–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Denisov G, Ho D, Mettler M, Candlin J, Hunkapiller T. Tracetuner—next generation base calling. A Celera Business: www.paracel.com; 2000:1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ning Z, Cox AJ, Mullikin JC. SSAHA: a fast search method for large DNA databases. Genome Res. 2001;11:1725–1729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Milne I, Bayer M, Cardle L, et al. Tablet–next generation sequence assembly visualization. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:401–402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Li H, Handsaker B, Wysoker A, et al. The sequence alignment/map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:2078–2079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Münzel T, Gori T, Bruno RM, Taddei S. Is oxidative stress a therapeutic target in cardiovascular disease? Eur Heart J. 2010;31:2741–2748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Li H, Horke S, Förstermann U. Vascular oxidative stress, nitric oxide and atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis. 2014;237:208–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Packard RRS, Libby P. Inflammation in atherosclerosis: from vascular biology to biomarker discovery and risk prediction. Clin Chem. 2008;54:24–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hou T, Tieu BC, Ray S, et al. Roles of IL‐6‐gp130 signaling in vascular inflammation. Curr Cardiol Rev. 2008;4:179–192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Woods A, Brull DJ, Humphries SE, Montgomery HE. Genetics of inflammation and risk of coronary artery disease: the central role of interleukin‐6. Eur Heart J. 2000;21:1574–1583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Haddy N, Sass C, Droesch S, et al. IL‐6, TNF‐alpha and atherosclerosis risk indicators in a healthy family population: the STANISLAS cohort. Atherosclerosis. 2003;170:277–283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Shinohara T, Takahashi N, Okada N, et al. Interleukin‐6 as an independent predictor of future cardiovascular events in patients with type‐2 diabetes without structural heart disease. J Clin Exp Cardiolog. 2012;3:209. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hassanzadeh M, Faridhosseini R, Mahini M, Faridhosseini F, Ranjbar A. Serum levels of TNF‐, IL‐6, and selenium in patients with acute and chronic coronary artery disease. Iran J Immunol. 2006;3:142–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Gotsman I, Stabholz A, Planer D, et al. Serum cytokine tumor necrosis factor‐alpha and interleukin‐6 associated with the severity of coronary artery disease: indicators of an active inflammatory burden? Isr Med Assoc J. 2008;10:494–498. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Ed Rainger G, Chimen M, Harrison MJ, et al. The role of platelets in the recruitment of leukocytes during vascular disease. Platelets. 2015;26:507–520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Veillard NR, Kwak B, Pelli G, et al. Antagonism of RANTES receptors reduces atherosclerotic plaque formation in mice. Circ Res. 2004;94:253–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Herder C, Peeters W, Illig T, et al. RANTES/CCL5 and risk for coronary events: results from the MONICA/KORA Augsburg case‐cohort. Athero‐express and CARDIoGRAM studies. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e25734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Cavusoglu E, Eng C, Chopra V, Clark LT, Pinsky DJ, Marmur JD. Low plasma RANTES levels are an independent predictor of cardiac mortality in patients referred for coronary angiography. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2007;27:929–935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Kraaijeveld AO, de Jager SCA, de Jager WJ, et al. CC chemokine ligand‐5 (CCL5/RANTES) and CC chemokine ligand‐18 (CCL18/PARC) are specific markers of refractory unstable angina pectoris and are transiently raised during severe ischemic symptoms. Circulation. 2007;116:1931–1941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Correia LCL, Andrade BB, Borges VM, et al. Prognostic value of cytokines and chemokines in addition to the GRACE Score in non‐ST‐elevation acute coronary syndromes. Clin Chim Acta. 2010;411:540–545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Lloyd‐Jones DM, Wilson PWF, Larson MG, et al. Framingham risk score and prediction of lifetime risk for coronary heart disease. Am J Cardiol. 2004;94:20–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Murabito JM, Pencina MJ, Nam B‐H, et al. Sibling cardiovascular disease as a risk factor for cardiovascular disease in middle‐aged adults. JAMA. 2005;294:3117–3123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Lieb W, Vasan RS. Genetics of coronary artery disease. Circulation. 2013;128:1131–1138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Zhao Y, Usatyuk PV, Gorshkova IA, et al. Regulation of COX‐2 expression and IL‐6 release by particulate matter in airway epithelial cells. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2009;40:19–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Tong Z, Li Q, Zhang J, Wei Y, Miao G, Yang X. Association between interleukin 6 and interleukin 16 gene polymorphisms and coronary heart disease risk in a Chinese population. J Int Med Res. 2013;41:1049–1056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Bhanushali AA, Das BR. Promoter variants in interleukin‐6 and tumor necrosis factor alpha and risk of coronary artery disease in a population from Western India. Indian J Hum Genet. 2013;19:430–436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Sun GQ, Wu GD, Meng Y, Du B, Li YB. IL‐6 gene promoter polymorphisms and risk of coronary artery disease in a Chinese population. Genet Mol Res. 2014;13:7718–7724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Aker S, Bantis C, Reis P, et al. Influence of interleukin‐6 G‐174C gene polymorphism on coronary artery disease, cardiovascular complications and mortality in dialysis patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2009;24:2847–2851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Jia X‐W, Tian Y‐P, Wang Y, Deng X‐X, Dong Z‐N. [Correlation of polymorphism in IL‐6 gene promoter with BMI, inflammatory factors, and pathogenesis and progression of CHD]. Zhongguo Shi Yan Xue Ye Xue Za Zhi. 2007;15:1270–1275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Saxena M, Agrawal CG, Srivastava N, Banerjee M. Interleukin‐6 (IL‐6)‐597 A/G (rs1800797) & ‐174 G/C (rs1800795) gene polymorphisms in type 2 diabetes. Indian J Med Res. 2014;140:60–68. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Spielman RS, Bastone LA, Burdick JT, Morley M, Ewens WJ, Cheung VG. Common genetic variants account for differences in gene expression among ethnic groups. Nat Genet. 2007;39:226–231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Balaresque PL, Ballereau SJ, Jobling MA. Challenges in human genetic diversity: demographic history and adaptation. Hum Mol Genet. 2007;16:R134–R139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]