Abstract

Background

MYBPC3 mutations have been described in dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM). A mutation, c.3373G>A, has been reported to cause autosomal recessive form of HCM. Here, we report that this mutation can cause autosomal dominant form of DCM.

Methods

Next‐generation sequencing using targeted panel of a total of 23 candidate genes and following Sanger sequencing was applied to detect causal mutations of DCM. Computational analyses were also performed using available software tools. In silico structural and functional analyses including protein modeling and prediction were done for the mutated MYBPC3 protein.

Results and Conclusion

Targeted sequencing showed one variant c.3373G>A (p.Val1125Met) in the studied family following autosomal dominant inheritance. Computational programs predicted a high score of pathogenicity. Secondary structure of the region surrounding p.Val1125 was changed to a shortened beta‐strand based on prediction of I‐TASSER and Phyre2 servers with high confidence value for the mutation. cMyBP‐C protein was modeled to 3dmkA. Our findings suggest that one single mutation of MYBPC3 may have different effects on the cellular mechanisms based of its zygosity. Various factors might be considered for explaining this phenomenon. This gene may have an important role in Iranian DCM and HCM patients.

Keywords: dilated cardiomyopathy, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, Iranian population, MYBPC3, p.Val1125Met

1. INTRODUCTION

MyBP‐C (myosin‐binding protein C) provides 2%‐4% of the mass of myofibrillar proteins.1 The cMyBP‐C contains three fibronectin type III and eight immunoglobulin‐like domains.2 It, however, might be involved in filament assembly and has an important role in regulation of contractility of cardiac muscle.3, 4 The MYBPC3 gene (11p11.2) structure and sequence have been determined in 1997.5 The cMyBP‐C is exclusively expressed during development of the human heart. It encompasses more than 21 Kbp and is composed of 35 exons. It interacts with other proteins and C‐terminal end domains are usually essential for interaction with titin, F‐actin and, myosin proteins.6, 7 This protein is phosphorylated by the protein kinase C and A and Ca+2/calmodulin kinase.8 Disrupted or reduced phosphorylation of this protein could result in a diseased phenotype.9 Two other MyBP‐C isoforms include slow skeletal (encoded by the MYBPC1 gene), and the fast skeletal (encoded by the MYBPC2 gene).

MYBPC3 mutation is the most common cause of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM),6 and it rarely can lead to other cardiac phenotypes such as dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) (CMD1MM; 615396). DCM as one of the leading causes of sudden cardiac death is a predominant form of inherited cardiac disease in humans, estimated to be 1 in 2500 individuals in general population.10 It is characterized by the enlargement of cardiac ventricular chamber and systolic dysfunction.11The prevalence of DCM has not been reported yet in Iran. The majority of DCM patients are sporadic; however, familial DCM has been determined in 20%‐35% of the patients.11 Familial DCM is usually inherited as autosomal dominant,12, 13, 14 although, autosomal recessive, X‐linked, or mitochondrial inheritance patterns are observed in a small number of cases15, 16, 17, 18 reflecting a wide locus heterogeneity for its etiology. Currently, more than 50 genes, which encode cytoskeletal, mitochondrial, nucleoskeletal, and calcium‐handling proteins, have been documented to cause DCM.15, 19 Reduced penetrance and phenotypic variability phenomena have also been reported in DCM.19 Locus heterogeneity and allelic disorders may also complicate this scenario; that is, the type of gene and mutation often leads to difference in the clinical features, age of onset, and prognosis of DCM.

Targeted next‐generation sequencing may be the best option to detect disease‐causing variants of the reported genes involved in heterogeneous disorders such as cardiomyopathies. Here, a heterozygous missense mutation in MYBPC3 gene, which has been previously described to cause HCM in its autosomal recessive form, is reported in a woman affected with DCM for the first time. In addition, computational analyses including protein modeling and prediction of pathogenicity are also presented.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Clinical evaluations

A woman with frequent palpitations and dyspnea was referred to Echocardiography Laboratory of Rajaee Heart Hospital. The clinical manifestation of the disease was started at the age of 30 years; EKG monitoring revealed multiple PVCs and nonsustain VTs; Echocardiographic examination revealed severe spherical left ventricular enlargement with severe systolic dysfunction (LVEF = 10%); also, there was severe diastolic dysfunction and mild pulmonary hypertension. DCM was diagnosed and full medical treatment was started in concomitant with ICD implantation. At the time of her initial visit to our clinic, the patient appeared in functional class II‐III with deep depression. After taking the signed informed consent, five milliliters peripheral blood was prepared for DNA extraction using the standard methods. The genetic analysis was performed for this patient.

2.2. Mutation screening and in silico analysis

The sequencing was performed using a custom‐designed Nimblegen chip capturing coding regions and exon‐intron boundaries of 23 candidate genes associated with DCM (Table S1). The enrichment was done using NimbleGen kit (NimbleGen, Roche, Basel, Switzerland). Genomic DNA was sequenced by targeted next‐generation sequencing (NGS) on an Illumina, Hiseq2000 (Illumina, San Diego, California, USA). Reads were, then, aligned using Burrows‐Wheeler aligner (BWA) on reference genome (hg19). SAMTools was applied for annotation. Filtering was performed based on the mentioned gene panel (Table S1). Variants were selected based on their frequency (minor allele frequency <0.1) in 1000 Genome and ExAC. The coverage of target genes was more than 95%, with sensitivity of more than 99%. Sanger sequencing was performed to confirm mutations. Briefly, the PCR products were sequenced using the BigDye termination method by sequencing analyzer of ABI 3130XL model (PE Applied BioSystems, Massachusetts, USA).

Online software tools and servers were applied to analyze the variants. Sorting intolerant from tolerant (SIFT),20 polymorphism phenotyping (PolyPhen‐2 v2.1),21 MutationTaster,22 Combined Annotation Dependent Depletion (CADD),23 and PROVEAN (Protein Variation Effect Analyzer)24 were used to predict the effects of mutation. A multiple sequence alignment of cMyBP‐C protein was performed using UniProtKB/Swiss‐Prot to check conserved domain among different paralogs and orthologs. The protein sequence of cMyBP‐C (UniProtKB/Swiss‐Prot Q14896) was compared using protein homology/analogy recognition engine V2.0 (Phyre2) to investigate effects of the variants on the structure and function of protein.25 In addition, iterative threading assembly refinement (I‐TASSER) server was used to predict the structure and function of mutated and normal protein.26 Modeling was performed using LOMETS threading program. In addition, interaction of cMyBP‐C protein was predicted by STRING database (version 10.5), a database for prediction of protein‐protein interactions. The interaction includes physical and functional associations derived from genomic context, high‐throughput experiments, co‐expression, automated text mining and previous knowledge.27

3. RESULTS

3.1. Clinical evaluation and genetic testing

The patient clinically diagnosed as DCM. A heterozygous missense variant, c.3373G>A, in exon 30 of the MYBPC3 (NM‐000256), was determined in the patient. The variant leads to a substitution of amino acid valine to methionine in position 1125 (p.Val1125Met) on the cMyBP‐C protein sequence (Figure 1). Subsequent Sanger sequencing confirmed the mutation. The variant was predicted to be damaging using pathogenicity prediction SIFT software (with Median conservation above 3.25). PolyPhen and MutationTaster software tools also predicted the mutation to be probably damaging and disease‐causing (Table S2).

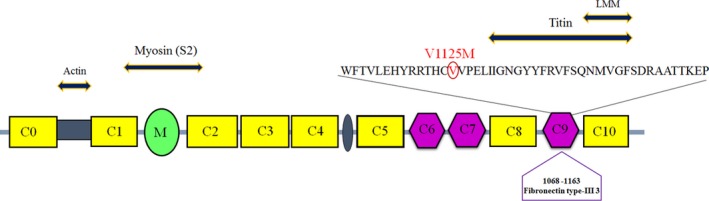

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of cMyBP‐C protein structure. cMyBP‐C is a multi‐modular protein composed of 8 immunoglobulin‐like (C0, C1, C2, C3, C4, C5, C8, C10) and 3 fibronectin type III (C6, C7, C9) domains. The cardiac isoform differs from the slow skeletal and the fast skeletal isoforms by cardiac‐specific regions (C0, M, 28‐amino acid insertion in C5). Between C0 and C1 exists a proline‐alanine rich domain (Pro‐Ala; PA). The location of DCM associated mutation identified in our study is shown above the C9 domain. The C9 contributed interactions have indicated as well

3.2. Structural and functional analyses of MYBPC3

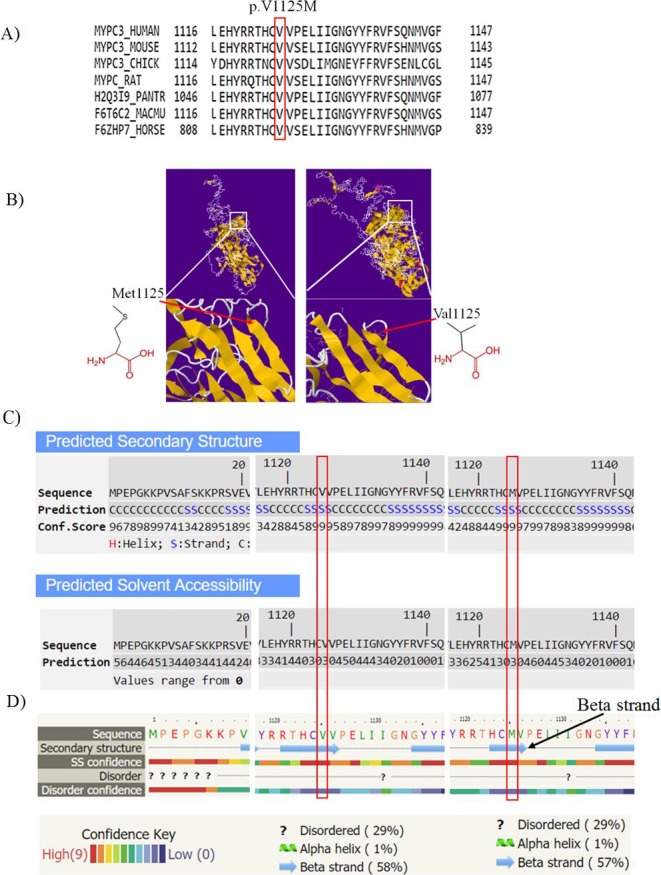

p.Val1125Met was subjected to sequence alignment among other species for conserved residues and the degree of conservation. Valine at position 1125 is highly conserved (Figure 2A). Secondary structure was predicted for p.Val1125Met with available tools. Protein model prediction using I‐TASSER is based on threading model. Secondary structure was predicted to be beta‐strand by I‐TASSER server with high confidence value for this variant (Figure 2B,C); solvent accessibility of the Val and Met amino acids was also determined as illustrated, Val1125 and Met amino acids at this position are both buried in protein; the accessibility to solvent of each of these amino acids is 3.

Figure 2.

A, Multiple amino acid alignment of cMyBP‐C protein adapted from UniProt protein family members. p.Val1125 as indicated in the box shows high conservation among different species. B, Cartoon structural model of human cMyBP‐C protein constructed by I‐TASSER based on 3dmkA (Down syndrome cell adhesion molecule (DSCAM) isoform 1.30.30, N‐terminal eight Ig domains) with a Normalized Z‐score >1 equal to 2.56; alignment with a Normalized Z‐score >1 mean a good alignment and vice versa. Structure prediction of cMyBP‐C protein was based on I‐TASSER server. The position of residue 1125 is shown in larger resolution in 3D structure. The schematic structures of the original (left) and the mutant (right) amino acid are also shown. C, Predicted secondary structure based on threading model by I‐TASSER, first line indicates the sequence, second line indicates the secondary structure, which is determined to be strand at position 1125 with the confidence score of 9 (third line). The range of confidence is 0‐9 wherein a higher score indicates a prediction with higher confidence. The solvent accessibility of the sequence is predicted as buried amino acid (range 0‐9 wherein a higher value means higher accessibility). D) Prediction of the secondary structure based on template/homology modeling by Phyre 2 server. First line indicates the amino acid sequence and the second line is the secondary structure prediction, which is determined as beta‐strand structure with the confidence value of high score (light red, depicted in line three) in mutated protein (Val1125), also this position is ordered which means it is not flexible and dynamic with high value (light red)

The top threading template predicted for p.Val1125Met was based on PDB 3dmkA (Down syndrome cell adhesion molecule (DSCAM) isoform 1.30.30, N‐terminal eight Ig domains)— identity 0.16; normalized Z score of the threading alignments = 2.55 and coverage = 0.58.26 The top threading template predicted for normal sequence was also based on 3dmkA —identity 0.16; normalized Z‐score = 2.56 and coverage = 0.58—showed higher Z‐score in comparison with the mutated sequence substitutions. TM‐score value shows the similarity of the predicted structures to the native structure. Indeed, TM‐align compares the first model with the PDB library models. The proposed model for p.Val1125Met aligned to PDB c3dmkA with TM‐score = 0.579. Structural similarity, therefore, could be reflecting of similar function.

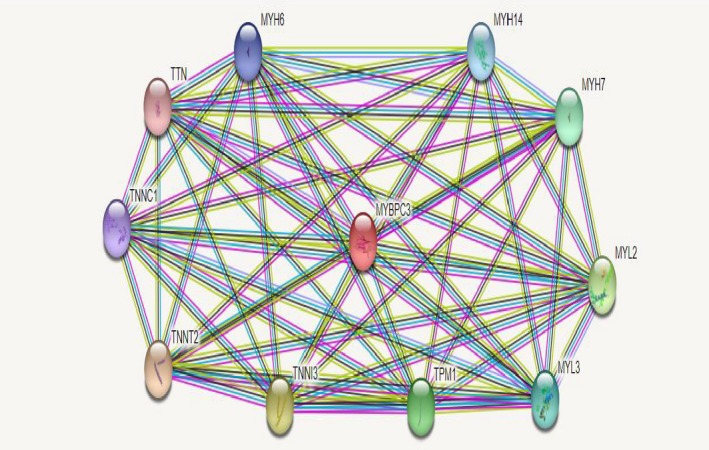

Using Phyre2 the p.Val1125Met was modeled based on c3dmkA with confidence score 100; identity 21% and coverage of 57%. As shown, a high secondary structure prediction confidence score (red) is observed at p.Val1125 position (Figure 2D). Moreover, interactions among cMyBP‐C and other proteins using STRING database emphasize the potential significant consequences of this mutation in development of cardiomyopathies. At least ten functional partners were predicted to interact with cMyBP‐C as follows: TNNT2, TNNI3, MYL2, TPM1, MYH6, MYH7, MYH14, MYH6, TNNC1, and TTN (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Protein‐protein interaction network of myosin‐binding protein C (cMyBP‐C) with STRING10. Predicted functional partners are as follows: TNNT2: Troponin T type 2 (cardiac); TNNI3: Troponin I type 3 (cardiac); MYL2: Myosin, light chain 2, regulatory, cardiac, slow; TPM1: Tropomyosin 1 (alpha) (284 aa); MYH6: Myosin, heavy chain 6, cardiac muscle, beta; MYH7: Myosin, heavy chain 7, cardiac muscle, beta; MYH14: Myosin, heavy chain 14, nonmuscle; MYH6: Myosin, heavy chain 6, cardiac muscle, alpha; TNNC1: Troponin C type 1 (slow); TTN: Titin

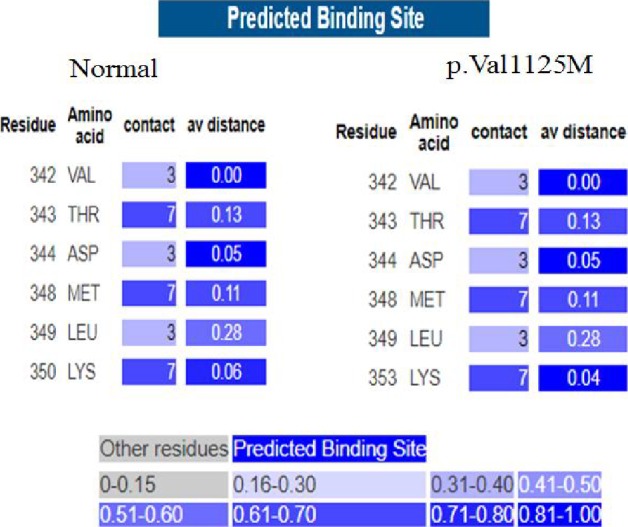

3DLigandSite was applied to predict the changes of binding sites in normal and mutated positions. There was no apparently effective change in binding sites when p.Val1125Met occurs (Figure 4), although, if p.Val1125Met occurs, some slight changes were observed in binding sites of the mutated protein as compared to normal protein.

Figure 4.

Phyre2 using 3DLigandSite server predicts potential binding sites of normal cMyBP‐C in comparison with the mutated protein. All of the predicted binding‐site residues are shown with details of the number of ligands that they contact, the average distance between the residue and the residue conservation score. As illustrated the residues’ average distance slightly is changed in p.Val1125Met (right side) in comparison with normal protein (left side); the range of average distance from conservation score of each residue is 0‐1.00 for each residue

4. DISCUSSION

MYBPC3 is one of the most common genes involved in HCM; its mutations are observed in about forty percent of the patients.6 Nevertheless, it has been shown that MYBPC3 mutations can cause various forms of cardiomyopathies such as DCM. Here, an individual affected by DCM is presented due to MYBPC3 mutation. Several studies have reported different mutations of MYBPC3 in DCM and other cardiomyopathies.28, 29, 30 Missense mutations located in MYBPC3 gene comprise the majority of DCM associated mutations.31, 32 To our knowledge, it has not been reported that one mutation expresses two different patterns of inheritance.

As known, DCM accounting for about half of all heart transplantations is a major cause of sudden death in young adults. Up to 35% of DCM cases show a familial pattern of inheritance, reflecting a strong genetic influence.33 In view of this fact, delineation of the genetic basis of DCM contributes to deeper understanding its pathogenesis and it may improve the diagnosis, prevention, and treatment of this disease. In this current study, we surprisingly detected a heterozygous MYBPC3 mutation (p.Val1125Met, rs121909378), in a patient with DCM. This mutation was first reported in a patient with autosomal recessive HCM.34 Frank‐Hansen et al in 2008 described a compound heterozygous genotype, c.906‐1G>C and p.Val1125Met mutations, in an individual with familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy 4.34 The proband and her affected sister carried both the c.906 –1G>C and the p.Val1125Met mutations. Her nephew presenting a borderline diagnosis of hypertrophy carried only the p.Val1125Met. Considering that the p.Val1125Met was found in our DCM patient, we can conclude that this mutation may act as a cause of DCM and not HCM. that is c.906‐1G>C has been dominantly lead to HCM in Frank‐Hansen study. Alternatively, the p.Val1125Met recessively could cause HCM and dominantly leads to DCM. Combinational effects of this mutation, therefore, with other mutated alleles are important to consider. Albeit, it should not be ignored, interactions with different isoforms of other proteins can affect the consequences of the mutations. Different dose of the mutated protein, unknown modifier factors and sexual and age‐related factors might be also considered for explaining this phenomenon.

Bioinformatics analyses using available prediction software tools showed the potential damaging role of the mutation. MYBPC3 encodes cMyBP‐C, a multi‐modular structural protein component of the sarcomere. The additional immunoglobulin‐like domain of cMyBP‐C at its N‐terminus (C0 domain), its multiple phosphorylation sites between the immunoglobulin‐like domains C1 and C2 and a 28‐proline‐rich amino acid insertion within the C5 domain, makes it as an ideal platform for signaling35, 36 (Figure 1). The predicted protein‐protein interaction network of MyBP‐C using STRING10 (Figure 3) showed it may interact with at least ten proteins including MYH7, MYH14, TTN, etc. In vitro studies showed cMyBP‐C binds sarcomere associated proteins such as F‐actin and thin filaments. It also could affect the activity of actin‐activated myosin ATPase. cMyBP‐C is a key constituent of the thick filaments localized to doublets in the C‐zone of the A‐band of the sarcomere, forming doublet appearing transverse stripes approximately 43 nm apart of each other in the cross‐bridge bearing region.37 The site of reported mutation is conserved and is located in fibronectin type III domain of cMyBP‐C (Figure 1, C9). This location may act as a site of interaction with other partners of cMyBP‐C. The mutation introduces an amino acid with different properties, which can disturb this domain and abolish its function. On the other hand, when p.Val1125Met occurs, each of them has its own specific properties; for example, the Met residue is bigger than the Val residue. The function of protein, thus, could be influenced because of this substitution.

Other studies have shown that genetic composition of our population has unique properties; that is the frequency and type of some mutations in subpopulations of Iran are different from each other and from other parts of the world. For example, the common mutation of GJB6, GJB6‐D13S1830, among European countries is not observed in our population.38, 39 The p.Val1125Met might be a common mutation among Iranian patients affected by cardiomyopathies. Further studies are required to elucidate the role of this mutation.

Our findings suggest that some mutations potentially could have different consequences when they are only mutation rather than in combination with other mutations. Deep understanding of the variants could help identifying allelic disorders. In addition, the role of other genetic variants should be considered if phenotypic variability observed.

Supporting information

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to thank the staffs at Cardiogenetic Research Laboratory, Rajaie Cardiovascular Medical and Research Center for their help in laboratory assistance.

Mahdieh N, Hosseini Moghaddam M, Motavaf M, et al. Genotypic effect of a mutation of the MYBPC3 gene and two phenotypes with different patterns of inheritance. J Clin Lab Anal. 2018;32:e22419 10.1002/jcla.22419

Contributor Information

Bahareh Rabbani, Email: baharehrabbani@yahoo.com.

Azin Alizadeh‐asl, Email: alizadeasl@gmail.com.

REFERENCES

- 1. Okagaki T, Weber FE, Fischman DA, et al. The major myosin‐binding domain of skeletal muscle MyBP‐C (C protein) resides in the COOH‐terminal, immunoglobulin C2 motif. J Cell Biol. 1993;123:619‐626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ackermann MA, Kontrogianni‐Konstantopoulos A. Myosin binding protein‐C: a regulator of actomyosin interaction in striated muscle. J Biomed Biotechnol. 2011;2011:636403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Luther PK, Vydyanath A. Myosin binding protein‐C: an essential protein in skeletal and cardiac muscle. J Muscle Res Cell Motil. 2011;31:303‐305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Finley NL, Cuperman TI. Cardiac myosin binding protein‐C: a structurally dynamic regulator of myocardial contractility. Pflugers Arch. 2014;466:433‐438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Carrier L, Bonne G, Bahrend E, et al. Organization and sequence of human cardiac myosin binding protein C gene (MYBPC3) and identification of mutations predicted to produce truncated proteins in familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Circ Res. 1997;80:427‐434. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Schlossarek S, Mearini G, Carrier L. Cardiac myosin‐binding protein C in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: mechanisms and therapeutic opportunities. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2011;50:613‐620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Behrens‐Gawlik V, Mearini G, Gedicke‐Hornung C, Richard P, Carrier L. MYBPC3 in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: from mutation identification to RNA‐based correction. Pflugers Arch. 2014;466:215‐223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Barefield D, Sadayappan S. Phosphorylation and function of cardiac myosin binding protein‐C in health and disease. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2010;48:866‐875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. van Dijk SJ, Dooijes D, dos Remedios C, et al. Cardiac myosin‐binding protein C mutations and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: haploinsufficiency, deranged phosphorylation, and cardiomyocyte dysfunction. Circulation. 2009;119:1473‐1483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hershberger RE, Hedges DJ, Morales A. Dilated cardiomyopathy: the complexity of a diverse genetic architecture. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2013;10:531‐547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hershberger RE, Siegfried JD. Update 2011: clinical and genetic issues in familial dilated cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;57:1641‐1649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Xu L, Zhao L, Yuan F, et al. GATA6 loss‐of‐function mutations contribute to familial dilated cardiomyopathy. Int J Mol Med. 2014;34:1315‐1322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Yuan F, Qiu XB, Li RG, et al. A novel NKX2‐5 loss‐of‐function mutation predisposes to familial dilated cardiomyopathy and arrhythmias. Int J Mol Med. 2015;35:478‐486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. McNally EM, Golbus JR, Puckelwartz MJ. Genetic mutations and mechanisms in dilated cardiomyopathy. J Clin Invest. 2013;123:19‐26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hershberger RE, Morales A, Siegfried JD. Clinical and genetic issues in dilated cardiomyopathy: a review for genetics professionals. Genet Med. 2010;12:655‐667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Murphy RT, Mogensen J, Shaw A, et al. Novel mutation in cardiac troponin I in recessive idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy. Lancet. 2004;363:371‐372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Roh JI, Cheong C, Sung YH, et al. Perturbation of NCOA6 leads to dilated cardiomyopathy. Cell Rep. 2014;8:991‐998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Man E, Lafferty KA, Funke BH, et al. NGS identifies TAZ mutation in a family with X‐linked dilated cardiomyopathy. BMJ Case Rep. 2013;2013: 10.1136/bcr-2012-007529 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Posafalvi A, Herkert JC, Sinke RJ, et al. Clinical utility gene card for: dilated cardiomyopathy (CMD). Eur J Hum Genet 2013;21(10): 10.1038/ejhg.2012.276 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kumar P, Henikoff S, Ng PC. Predicting the effects of coding non‐synonymous variants on protein function using the SIFT algorithm. Nat Protoc. 2009;4:1073‐1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Adzhubei IA, Schmidt S, Peshkin L, et al. A method and server for predicting damaging missense mutations. Nat Methods. 2010;7:248‐249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Schwarz JM, Cooper DN, Schuelke M, Seelow D. MutationTaster2: mutation prediction for the deep‐sequencing age. Nat Methods. 2014;11:361‐362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kircher M, Witten DM, Jain P, et al. A general framework for estimating the relative pathogenicity of human genetic variants. Nat Genet. 2014;46:310‐315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Choi Y, Sims GE, Murphy S, Miller JR, Chan AP. Predicting the functional effect of amino acid substitutions and indels. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e46688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kelley LA, Mezulis S, Yates CM, Wass MN, Sternberg MJ. The Phyre2 web portal for protein modeling, prediction and analysis. Nat Protoc. 2015;10:845‐858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Yang J, Yan R, Roy A, et al. The I‐TASSER Suite: protein structure and function prediction. Nat Methods. 2015;12:7‐8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Szklarczyk D, Morris JH, Cook H, et al. The STRING database in 2017: quality‐controlled protein‐protein association networks, made broadly accessible. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45(D1):D362‐D368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Daehmlow S, Erdmann J, Knueppel T, et al. Novel mutations in sarcomeric protein genes in dilated cardiomyopathy. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2002;298:116‐120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Konno T, Shimizu M, Ino H, et al. A novel missense mutation in the myosin binding protein‐C gene is responsible for hypertrophic cardiomyopathy with left ventricular dysfunction and dilation in elderly patients. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;41:781‐786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hershberger RE, Norton N, Morales A, et al. Coding sequence rare variants identified in MYBPC3, MYH6, TPM1, TNNC1, and TNNI3 from 312 patients with familial or idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy. Circ Cardiovasc Genet. 2010;3:155‐161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ashrafian H, Watkins H. Reviews of translational medicine and genomics in cardiovascular disease: new disease taxonomy and therapeutic implications cardiomyopathies: therapeutics based on molecular phenotype. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;49:1251‐1264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Chang AN, Potter JD. Sarcomeric protein mutations in dilated cardiomyopathy. Heart Fail Rev. 2005;10:225‐235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Grunig E, Tasman JA, Kucherer H, et al. Frequency and phenotypes of familial dilated cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1998;31:186‐194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Frank‐Hansen R, Page SP, Syrris P, et al. Micro‐exons of the cardiac myosin binding protein C gene: flanking introns contain a disproportionately large number of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy mutations. Eur J Hum Genet. 2008;16:1062‐1069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Pfuhl M, Gautel M. Structure, interactions and function of the N‐terminus of cardiac myosin binding protein C (MyBP‐C): who does what, with what, and to whom? J Muscle Res Cell Motil. 2012;33:83‐94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Sadayappan S, de Tombe PP. Cardiac myosin binding protein‐C: redefining its structure, function. Biophys Rev 2012;4:93‐106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Luther PK, Bennett PM, Knupp C, et al. Understanding the organisation and role of myosin binding protein C in normal striated muscle by comparison with MyBP‐C knockout cardiac muscle. J Mol Biol. 2008;384:60‐72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Riazalhosseini Y, Nishimura C, Kahrizi K, et al. Δ (GJB6‐D13S1830) is not a common cause of non‐syndromic hearing loss in the Iranian population. Arch Iranian Med. 2005;8:104‐108. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Mahdieh N, Raeisi M, Shirkavand A, et al. Investigation of GJB6 large deletions in Iranian patients using quantitative real‐time PCR. Clin Lab. 2010;56:467‐471. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials