Abstract

Background

Among the fungal pathogens, Candida species are the most common cause of urinary tract infection (UTI). Some predisposing factors such as diabetes mellitus, urinary retention, urinary stasis, renal transplantation, and hospitalization can increase the risk of candiduria. The aim of this cross‐sectional study was to evaluate candiduria among type 2 diabetic patients and identification of the Candida isolates.

Method

Four hundred clean‐catch midstream urine specimens were obtained from patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. The specimens were centrifuged and the sediments were examined by direct examination and cultured on Sabouraud dextrose agar. The plates were incubated for 2‐3 days at 35°C. The Candida colonies were counted and purified using CHROMagar Candida. The isolates were identified by matrix‐assisted laser desorption ionization‐time of flight mass spectrometry (MALDI‐TOF MS) system.

Results

Of the 400 urine specimens, 40 (10%) had positive cultures for Candida species with a colony count of ≥1 × 103 colony forming units (CFU)/mL. The frequencies of the Candida species were as follows: C. albicans (n = 19, 47.5%), C. glabrata (n = 15, 37.5%), C. kefyer (n = 4, 10%) and C. krusei (n = 2, 5%). Seventy‐three (88%) of the patients with candiduria had hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) levels above 7%.

Conclusion

The rate of candiduria was relatively high in type 2 diabetic patients and they were also suffering from a lack of proper blood glucose control. Although the frequency of non‐albicans Candida species had not significantly higher than C. albicans, however, they obtained more from those with symptomatic candiduria.

Keywords: candiduria, diabetic patients, MALDI‐TOF, Mashhad, non‐albicans Candida

1. INTRODUCTION

Urinary tract infection (UTI) is one of the most common infections encountered in clinical practice.1 They can be caused by a range of pathogens such as bacteria, fungi, parasites, and viruses.2 However, among the fungal agents and the opportunistic fungal infections involving urinary system, Candida species are the most rampant causes of UTI.3 During past 3 decades, several reports have indicaed a dramatic increase in the prevalence of candiduria.4 Candida spp. can be colonized in the lower or upper urinary tract system and create pyelonephritis, cystitis, urethritis and prostatitis in men.5 They might even appear in the upper urinary tract from the bloodstream or raise the urinary tract from a focus of Candida colonization at near the urethra.6 Although C. albicans is the most commonly isolated species in candiduria, the incidence of non‐albicans species is ever increasing.7 Predisposing conditions such as diabetes mellitus, urinary stasis, renal transplantation, and hospitalization can increase the risk of candiduria. However, diabetes is one of the main risk factors to develop it.4, 8 Candiduria can lead to some serious complications among susceptible patients. Thus, following up of candiduria in susceptible individuals (especially, with high counts of Candida) can decrease the probable complications. Because of the presence of Candida in urine may represent a range of conditions that require accurate interpretation, from contamination of specimen to infections of the kidney and collecting systems to a life‐threatening, disseminated candidiasis.6 In addition, identification of Candida spp. and targeted antifungal therapy can reduce antifungal drug resistance among Candida species.9 The present study was performed to evaluate candiduria among type 2 diabetic patients and their blood glucose control. In addition, the Candida isolates were identified using matrix‐assisted laser desorption ionization‐time of flight mass spectrometry (MALDI‐TOF MS) system.

2. MATERIAL AND METHODS

2.1. Sampling and isolates

A cross‐sectional study was conducted during November 2015‐ September 2016 at diabetes care unit of health center (NO.3), Mashhad University of Medical Sciences (MUMS). Official permission for this study was obtained for all diabetic patients (a fasting blood sugar ≥ 126 mg/dL) who were referred to the diabetes care unit. The questionnaire forms were filed for every patient. The inclusion criteria included only the patients that had diabetes and no other major underlying disease (including hematological stem cell and solid organ transplantations, prolonged therapy with high‐dose corticosteroids, hematological malignancies and AIDS), non pregnant and not taking antifungal drugs during the past 1 month.

Each diabetic patient was guided to roll up a clean‐catch midstream urine specimen. About 15 mL urine specimen was collected in a sterile container from each diabetic patient. The urine pH and glycosuria was recorded for every specimen by the urine test strip. Also, the hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) levels in whole blood of the diabetic patients were measured. After mixing and homogenization of the urine, a inoculating loop with a volume of 0.01 μL was plated on Sabouraud dextrose agar (SDA) with chloramphenicol (Merk, Germany) using a glass spreader. The plates were incubated for 2‐3 days at 35°C. Rest of the urine was centrifuged at 2500 rpm for 5 minutes. The pellet was vortexed until it was completely resuspended. Then, the prepared suspension was examined by direct microscopic examination.

In the culture plates, the colonies obtained after the incubation period were counted and only the specimens with a colony count of ≥1 × 103 colonies were considered as positive cultures for Candida.10 The Candida isolates were purified by color of the colony on CHROMagar Candida medium.

2.2. Identification of yeast species by MALDI‐TOF MS

The obtained single yeast colonies were transferred and cultured on SDA for 24 hour at 35°C. According to the Bruker Daltonics (MALDI‐TOF) protocol for the identification of yeast isolates, the ethanol‐formic acid extraction procedure was followed11: the fresh colonies were transferred in 1.5 mL microtubes and mixed thoroughly in 300 μL of distilled ultra‐pure water. Nine hundred microliters of pure ethanol 100% were added to tubes and after vortexing, they were centrifuged at 14 000 rpm for 2.5 minutes. The supernatant was discarded and the pellet was dried for 15‐20 minutes. Thirty microliters of 70% aqueous formic acid was added and mixed thoroughly. Then, 50 μL of acetonitrile was added and the mixture was centrifuged at 14 000 rpm for 2.5 minutes. One microliter of the yeast extract supernatant was placed onto the polished steel MALDI target plate (Bruker Daltonics, Bremen, Germany) in duplicate and allowed to dry at room temperature. One microliter of Matrix solution was used to overlay each sample, and the plate was air‐dried at room temperature. The plate was loaded into the Bruker Auto flex III MALDI‐TOF MS (Bruker Daltonics). The spectra were analyzed using the Flex Control 3.1 software and MALDI Biotyper OC version 3.1 and a score of ≥2 indicated confidence to the species level.

2.3. Data analysis

The data analyses were performed using SPSS software (version 16). Fisher's exact test was used in the analysis of contingency tables. A P value less than .05 was considered significant.

3. RESULTS

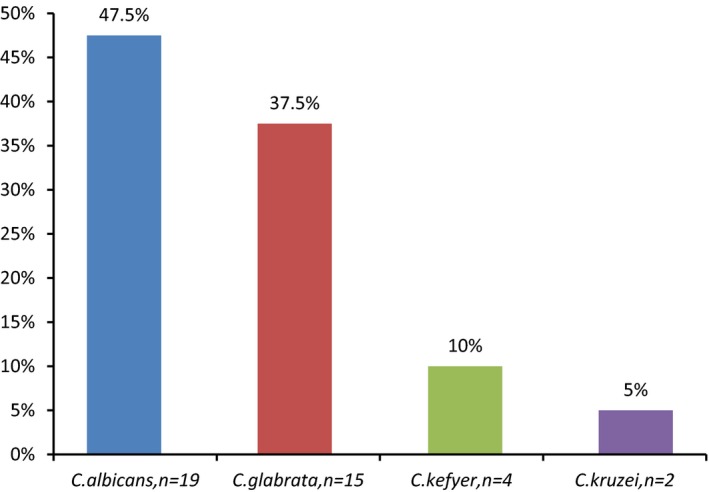

Among the 400 diabetic patients, including 256 females (64%) and 144 males (36%), 40 patients (12.5% were men and 87.5% were women) had positive cultures for Candida. They had a significant candiduria with a colony count of ≥1 × 103 colony forming units (CFU)/mL. According to the statistical analysis, there was a significant association between female gender and candiduria (P = .006). The frequency of identified Candida species in this study is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The frequency of Candida species isolated from urine of type 2 diabetic patients

Considering the colony count of ≥1 × 104 CFU/mL, the candiduria prevalence is 7%. According to this, the frequencies of the Candida species were as follows: C. albicans (n = 13, 46.4%), C. glabrata (n = 12, 42.8%), C. kefyer (n = 2, 7.2%) and C. krusei (n = 1, 3.6%).

The urine pH was from 5 to 8 among the diabetic patients and most patients with candiduria had a urine pH range of 5‐6. The patients with candiduria had a glycosuria in a trace amount (≥3 pluses), that 55% (n = 22) were as ≥3 pluses. Additionally, the HbA1c level was more than 7% in 32 (80%) of the diabetic patients with candiduria.

Table 1 shows the gender of type 2 diabetic patients and the relationship between candiduria and other urinary and blood factors.

Table 1.

The gender of type 2 diabetic patients and relationship between candiduria and other factors in them

| Variable | Positive culture for Candida | Negative culture for Candida | Total | P ‐value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 5 | 139 | 144 | .001 |

| Female | 35 | 221 | 256 | |

| Total | 40 | 360 | 400 | |

| Urine pH | ||||

| 5‐6 | 38 | 208 | 246 | .002 |

| >6‐7 | 2 | 142 | 144 | |

| >7‐8 | 0 | 10 | 10 | |

| Total | 40 | 360 | 400 | |

| HbA1c levels (%) | ||||

| ≤7 | 8 | 252 | 260 | .001 |

| >7 | 32 | 108 | 140 | |

| Total | 40 | 360 | 400 | |

| Glycosuria | ||||

| Negative | 0 | 15 | 15 | .001 |

| Trace | 2 | 91 | 93 | |

| One plus | 4 | 172 | 176 | |

| Two pluses | 12 | 72 | 84 | |

| ≥Three pluses | 22 | 10 | 32 | |

| Total | 40 | 360 | 400 | |

HbA1c, Hemoglobin A1c or glycated hemoglobin.

4. DISCUSSION

The current study has described a screening program to evaluate candiduria among type 2 diabetic patients and the identification of the Candida isolates using MALDI‐TOF MS system. The assay was applied to analysis of 400 urine specimens and the urine pH and glycosuria. Also, the serum hemoglobin HbA1c levels of the patients were measured.

There is little data of the incidence candiduria among different patient around the world.6, 12, 13 It is even considered one of the most controversial issues in management protocols and the optimal treatment options have not been standardized. Although most patients with candiduria are asymptomatic, and yeast agents are noted in the urine as an expected finding on a routine analysis or urine culture, but in some cases, it has been considered an important problem and can cause some complications.14, 15

Some recent studies have shown that the rate of candiduria has increased and non‐albicans Candida species are steadily increasing as the etiological cause of fungal UTI. However, all Candida species are capable of causing UTI.16, 17, 18 There are many predisposing factors for candiduria and diabetes is one of the main factors.4, 8 So, Kauffman et al3 emphasized on early detection of candiduria among diabtic patients.

In this study, the prevalence of candiduria among type 2 diabetic patients was found to be %10. In a similar study it has been reported in Ethiopia19 and Saudi Arabia,20 the prevalence was 8.3% and 8% respectively. Although, it has also been reported in other regions of the world between 2.27% and 30% in various studies performed on various patients.13, 21, 22 The conflicting results of these studies may be due to differences in the sample size, population studied, and even the location and geographical area. However, the important point that seems to be very effective in reporting the prevalence rate is the criteria for determining of candiduria. In the current study, a colony count of ≥1 × 103 CFU/mL in urine culture was considered as candiduria. In other studies, a colony count of ≥1 × 104 CFU/mL in urine culture was considered as candiduria. While in various studies, the definition of a positive urine culture is considered variable in the patients. In addition, this is further complicated by lack of defined laboratory criteria for the diagnosis as fungal UTI. Eventually, it will depend on the presence of symptoms and the method of urine specimen collection.23 In a similar study conducted in Iran, based on the criteria of this study, the candiduria prevalence was 9.8% and this percantage is consistent with the results of the current study.10 Considering the colony count of ≥1 × 104 CFU/mL in this study, the candiduria prevalence will be 7%. However, this difference in the results is not significant.

The candiduria had a significantly higher rate in females (87.5%) than males (12.5%). The main possible factors may be the anatomical status of urinary system in women, vaginal infections and its proximity to anal. Other studies have also presented the same results.21, 22, 23 Therefore, the candidiuria in women should be defined carefully, especially in diabetic patients. In the present study, the frequency of non‐albicans Candida species (52.5%) was higher than C. albicans (47.5%). Among non‐albicans Candida species, C. glabrata (37.5%) had the highest frequency. However, among Candida species, C. albicans was the most common cause detected in the patients, and C. glabrata was the second most common cause detected. Unlike most reports from throughout the world and that of Iran, C. albicans is considered as the significantly dominant causative agent for candidiasis,24, 25, 26, 27 though in this study, it was not observed considerably in the diabetic patients with candiduria. There is an agreement on the high prevalence of non‐albicans Candida species especially C. glabrata in the diabetic patients in Iran and other countries.10, 19, 28, 29 The relatively high frequency of C. glabrata detection from these patients may be because of the higher prevalence of the fungus in them or be due to the antifungal resistance in Candida species. Although among the Candida spp., C. albicans azole resistance rates are generally low. However, the prevalence of other species resistant to triazoles especially fluconazole, such as C. krusei and C. glabrata, is increasing.30 Hence, because of more resistance of non‐albicans Candida to antifungal drugs, accurate identification of Candida species, especially in symptomatic candiduria seem to be necessary. One of the modern methods to identify Candida species is MALDI‐TOF MS that this study used for identification the Candida isolates. Traditional methods can not differentiate Candida species correctly. Therefore, the reports in various studies that have used traditional or nonmolecular techniques cannot be termed reliable.31

Uncontrolled (or poorly controlled) diabetes can increase plasma glucose and create acidosis, and make patients susceptible to various infections.32 The important factors which can influence the transition from the morphological change from yeast to hyphal or pseudohyphal growth of Candida in the urinary tract are acid pH, proteinuria and limited nutrients. Indeed, the rates of germination and elongation of hyphae can be stimulated at low pH in the presence of nitrogenous compounds in the urine of predisposed patients.4 In addition, the pH‐regulated expression of essential genes could be vital to the organism's survival.4 In the study, association between candiduria with glycosuria, acidic urine pH and poor control diabetes (HbA1c > 7%) was a significant correlation. These findings had a agreement with studies of Yismaw et al,19 Paul et al33 and Geerling et al34 This can be due to an increased susceptibility to Candida colonization rates.

One of the limitations of this work was the small population size with clinical signs and symptoms of a UTI. Among the type 2 diabetic patients with candiduria, only 6 (15%) had symptoms of UTI. However, candiduria should follow up among the patients because it can lead to some serious complications, even those with the asymptomatic forms.

This study showed a candiduria with a relatively high prevalence among type 2 diabetic patients. Most of them suffer from a lack of proper blood glucose control. The frequency of non‐albicans Candida species, especially C. glabrata was high. However, the timely recognition of candiduria among type 2 diabetic patients, especially those with symptomatic forms and accurate identification of Candida isolates is recommended to prevent the development of organ failure and other complications.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We thank the staff of Medical Mycology and Parasitology laboratory in Ghaem Hospital in Mashhad University of Medical Sciences (MUMS). Also, we thank professor Anuradha Chowdhary and the staff of the department of Medical Mycology, Vallabhbhai Patel Chest Institute, University of Delhi, India for their guidance and helps. This work was as a master thesis of Alireza Esmailzadeh in MUMS and was financially supported by the Deputy of Research, MUMS, Mashhad, Iran (grant No. 940813).

Esmailzadeh A, Zarrinfar H, Fata A, Sen T. High prevalence of candiduria due to non‐albicans Candida species among diabetic patients: A matter of concern?. J Clin Lab Anal. 2018;32:e22343 10.1002/jcla.22343

Funding information

This work was financially supported by MUMS, Mashhad, Iran (grant No. 940813)

REFERENCES

- 1. Drekonja DM, Johnson JR. Urinary tract infections. Prim Care. 2008;35:345‐367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bensman A, Dunand O, Ulinski T. Urinary tract infections In: Avner E, Harmon W, Niaudet P, Yoshikawa N, eds. Pediatric Nephrology: Sixth Completely Revised, Updated and Enlarged Edition. Berlin: Springer Berlin Heidelberg; 2009:1297‐1310. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kauffman CA, Vazquez JA, Sobel JD, et al. Prospective multicenter surveillance study of funguria in hospitalized patients. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;30:14‐18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Sobel JD, Fisher JF, Kauffman CA, Newman CA. Candida urinary tract infections ‐ epidemiology. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52(SUPPL. 6):S433‐S436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Achkar JM, Fries BC. Candida infections of the genitourinary tract. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2010;23:253‐273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Fisher JF. Candida urinary tract infections ‐ epidemiology, pathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment: Executive summary. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52(SUPPL. 6):S429‐S432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Sardi JCO, Scorzoni L, Bernardi T, Fusco‐Almeida AM, Mendes Giannini MJS. Candida species: current epidemiology, pathogenicity, biofilm formation, natural antifungal products and new therapeutic options. J Med Microbiol. 2013;62(PART1):10‐24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cooke FJ. Infections in people with diabetes. Medicine. 2015;43:41‐43. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Alcazar‐Fuoli L, Mellado E. Current status of antifungal resistance and its impact on clinical practice. Br J Haematol. 2014;166:471‐484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Falahati M, Farahyar S, Akhlaghi L, et al. Characterization and identification of candiduria due to Candida species in diabetic patients. Curr Med Mycol. 2016;2:10‐14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Jensen RH, Arendrup MC. Candida palmioleophila: characterization of a previously overlooked pathogen and its unique susceptibility profile in comparison with five related species. J Clin Microbiol. 2011;49:549‐556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Fakhri A, Navid M, Seifi Z, Zarei MA. The frequency of candiduria in hospitalized patients with depressive syndrome. J Renal Inj Prev. 2014;3:97‐98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Yashavanth R, Shiju MP, Bhaskar UA, Ronald R, Anita KB. Candiduria: prevalence and trends in antifungal susceptibility in a tertiary care hospital of Mangalore. J Clin Diagn Res. 2013;7:2459‐2461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kauffman CA, Fisher JF, Sobel JD, Newman CA. Candida urinary tract infections ‐ diagnosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52(SUPPL. 6):S452‐S456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Sagué CMB, Jarvis WR. Secular trends in the epidemiology of nosocomial fungal infections in the United States, 1980–1990. J Infect Dis. 1993;167:1247‐1251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Binelli CA, Moretti ML, Assis RS, et al. Investigation of the possible association between nosocomial candiduria and candidaemia. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2006;12:538‐543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Jamil S, Jamil N, Saad U, Hafiz S, Siddiqui S. Frequency of Candida albicans in patients with funguria. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2016;26:113‐116. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Silva S, Negri M, Henriques M, Oliveira R, Williams DW, Azeredo J. Candida glabrata, Candida parapsilosis and Candida tropicalis: biology, epidemiology, pathogenicity and antifungal resistance. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2012;36:288‐305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Yismaw G, Asrat D, Woldeamanuel Y, Unakal C. Prevalence of candiduria in diabetic patients attending Gondar University Hospital, Gondar, Ethiopia. Iran J Kidney Dis. 2013;7:102‐107. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. El Sheikh SM, Johargi AK. Bacterial and Fungal infections among diabetics. Med Sci J. 2000;8:41‐48. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Richards MJ, Edwards JR, Culver DH, Gaynes RP. Nosocomial infections in pediatric intensive care units in the United States. National Nosocomial Infections Surveillance System. Pediatrics. 1999;103:e39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Silva V, Hermosilla G, Abarca C. Nosocomial candiduria in women undergoing urinary catheterization. Clonal relationship between strains isolated from vaginal tract and urine. Med Mycol. 2007;45:645‐651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Nitzan O, Elias M, Chazan B, Saliba W. Urinary tract infections in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: review of prevalence, diagnosis, and management. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes. 2015;8:129‐136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kord Z, Fata A, Zarrinfar H. Molecular identification of candida species isolated from patients with vulvovaginitis for the first time in mashhad. Iran J Obstet Gynecol Infertil. 2017;20:50‐57. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Khorsand I, Ghanbari Nehzag MA, Zarrinfar H, et al. Frequency of variety of candida species in women with candida vaginitis referred to clinical centers of Mashhad, Iran. Iran J Obstet Gynecol Infertil. 2015;18:15‐22. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Zarrinfar H, Kaboli S, Dolatabadi S, Mohammadi R. Rapid detection of Candida species in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid from patients with pulmonary symptoms. Braz J Microbiol. 2016;47:172‐176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Vazquez JA, Sobel JD. Mucosal candidiasis. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2002;16:793‐820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Nayman Alpat S, Özgüneş I, Ertem OT, et al. Evaluation of risk factors in patients with candiduria. Mikrobiyoloji Bulteni. 2011;45:318‐324. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Jain N, Kohli R, Cook E, Gialanella P, Chang T, Fries BC. Biofilm formation by and antifungal susceptibility of Candida isolates from urine. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2007;73:1697‐1703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Walsh TJ, Gamaletsou MN. Treatment of fungal disease in the setting of neutropenia. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2013;2013:423‐427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Arvanitis M, Anagnostou T, Fuchs BB, Caliendo AM, Mylonakis E. Molecular and nonmolecular diagnostic methods for invasive fungal infections. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2014;27:490‐526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Casqueiro J, Casqueiro J, Alves C. Infections in patients with diabetes mellitus: a review of pathogenesis. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2012;16:27‐36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Paul N, Mathai E, Abraham OC, Michael JS, Mathai D. Factors associated with candiduria and related mortality. J Infect. 2007;55:450‐455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Geerlings S, Fonseca V, Castro‐Diaz D, List J, Parikh S. Genital and urinary tract infections in diabetes: impact of pharmacologically‐induced glucosuria. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2014;103:373‐381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]