Abstract

Youth substance use was investigated in a sample of Mexican-origin mothers and youth (93 dyads totaling 186 individuals). We tested the hypotheses that both acculturation and inner-city risk factors impact substance use largely because they undermine family relationships. Mothers and youth completed self-report measures of acculturation and enculturation. Youth completed questionnaires of family relationships, inner-city risk factors, and substance use. Youth substance use was measured with an index of life-time alcohol, tobacco, and marijuana use based on the Youth Risk Behavior Survey. As predicted, mother-youth (dyadic) acculturation / enculturation, as well as exposure to violence, were significantly associated with substance use. Family cohesion mediated the impact of violence exposure on substance use. However, both cohesion and violence had unique and significant associations with substance use. Furthermore, family relationships did not mediate the link between substance use and mother-youth acculturation or mother-youth enculturation. Results underscore the need to develop and test hypotheses that link Latino youth substance use with both acculturation and inner-city contexts that do not solely rely on family relationships as mediators.

While youth substance use does not occur with greater frequency among Latinos compared to other ethnic/racial groups (Szapocznik, Prado, Burlew, Williams, & Santisteban, 2007), lifetime rates of substance use among Latinos are increasing (Vega & Gil, 1999). Furthermore, Latinos have been found to be at greater risk for correlates of substance use, such as school failure, compared to other ethnic groups (Laird, Cataldi, KewalRamani, & Chapman, 2008). Thus, understanding the risk and protective processes of substance use will shed light on the psychosocial adjustment of the Latino youth population in the U.S.

Acculturation, Family Context and Youth Substance Use

Longer exposure to the dominant U.S. culture is associated with increased substance use among Latino adults and youth (Amaro, Whitaker, Coffman, & Heren, 1990; Gil, Wagner, & Vega, 2000; Grant et al., 2004; Vega, Sribney, & Achara-Abrahams, 2003). To explain this link among Latino youth, researchers have advanced the acculturation-gap distress theory. Acculturation refers to the acquisition of a new society’s language, customs and values by immigrant individuals (Berry, 1997). The theory posits that family relationships may deteriorate when gaps arise in acculturation between parents and youth (Szapocznik & Kurtines, 1993). Quality of family relationships may decrease when youth readily adopt the new (United Sates) culture that tends to place high value on youth’s individual rights and independence, while parents adhere to the Latino culture of origin which places high value on parental authority. Notably, in the acculturation gap distress theory, the relation between substance use and high youth acculturation (along with low parental acculturation) is mediated by deterioration of family relationships such as erosion in family cohesion (Gil et al., 2000).

The family mediation hypothesis highlights the important role of the family in substance use. Family relationships are robust predictors of substance use in the general population (Hawkins Catalano, & Miller, 1992; Pertraitis, Flay, & Miller, 1995). Family cohesion and closeness have been found to be related to lower levels of substance use and disposition to deviance among predominantly Cuban American youth in Florida (Apospori, Vega, Zimmerman, Wargeit, & Gil, 1995; Gil et al., 2000; Vega, Gil, Warheit, Zimmerman, & Apospori, 1993). Moreover, other key family variables such as parental monitoring have been found to be associated with substance use among predominantly Mexican American youth sampled in Oregon (Martinez, 2006).

Studies testing the acculturation gap distress hypothesis and substance use have yielded equivocal results. Martinez (2006) found that parent-youth acculturation gaps were linked with youth substance use in a sample of predominantly Mexican American mother-youth dyads. Additionally, he found support for the mediating role of family relationships. In contrast, Vega and Gil (1998) did not find that parent-youth acculturation and substance use were related among youth of Cuban origin. Thus, further empirical work is called for.

A parallel literature on Latino youth mental health and acculturation gaps is informative to the study of Latino youth substance use. Birnam (2006) as well as Lau et al. (2005) found that high mother acculturation and low youth acculturation predicted poor youth mental health. Note that those findings do not follow the pattern predicted by acculturation-gap theory (i.e., low mother acculturation / high youth acculturation predicting poor mental health). Such findings indicate that the latter specific pattern of youth-parent acculturation may not be the only one predictive of youth mental health problems and thus highlight the need to study parent-youth acculturation gaps broadly.

Inner-City Stressors and Youth Substance Use

In addition acculturation and family contexts, Latino youth substance use researchers have regarded inner-city stressors as risk factors to substance use (e.g., Martinez, Eddy, & Degarmo, 2003, Vega & Gil 1999). The call for attention to inner-city stressors by Latino substance use researchers is consistent with research with the general population which has shown that neighborhood violence and economic hardship predict higher substance use among youth (Hawkins et al., 1992; Pertraitis et al., 1995). Furthermore, ecological models of substance use posit that family relationships are mediators of the influences of cultural and neighborhood domains on youth substance use (Szapocznik & Coatsworth, 1999). However, there is also a paucity of research on Latino youth substance use that examines the impact of inner-city stressors on substance use and the mediating role of the family. This is an important gap in the literature because many Latino families and youth live in inner-city environments and are likely exposed to neighborhood violence and economic hardship (Gonzales, Knight, Morgan-Lopez, Saenz, & Sirolli, 2002; Vega & Gil, 1999).

Current Study

We tested the link between youth substance use and both mother-youth acculturation and inner-city stressors. We operationalized mother-youth (dyadic) acculturation with a moderation approach (see Birnam, 2006) which did not impose a priori a particular pattern of acculturation (e.g., youth high and mother low) as a risk factor. We used behavioral / linguistic indices of both participation in the new culture (acculturation) as well as in the culture of origin (enculturation) as recommended by Latino youth researchers (Szapocznik & Kurtines, 1980; Gonzales et al., 2002). Enculturation refers to the retention of the language, customs, and values dominant in the country of origin and has received little attention in the Latino youth substance use literature. Inner-city stressors were operationalized with youth-reported levels of economic hardship and exposure to violence. We also tested the degree to which family cohesion or parental monitoring mediates the impact of inner-city stressors and/or mother-youth acculturation/enculturation on substance use. The latter tests of mediation address a subsidiary research question: Are mother-youth acculturation/enculturation related to family relationships?

Method

Participants

Mexican American mother-youth dyads (N=93) were recruited in a large, urban, Midwestern city. Youth included 47 girls and 45 boys (one did not report gender) with a mean age of 15.4 years (SD = .95). All youth were in the 9th or 10th grade and attended the same public high school which was the recruiting site. All mothers and youth self-identified as Mexican or Mexican-American. The high school was located in an enclave of Latino immigrants (predominantly of Mexican descent) with approximately 47,000 residents. Thus, the demographics of the community differ from national trends (U.S. Census, 2000; Great Cities Institute, n.d.). The community is predominantly Latino or Hispanic (63% vs. 13% in the U.S.) and approximately two-thirds speak a language other than English at home (63% vs. 18% in the U.S.). The levels of gang violence have been characterized as second highest in the U.S. (behind East Los Angeles). Average family size is four (vs. three in the U.S) and 25% live below poverty levels (vs. 9% in the U.S.).

Mothers reported a median annual family income of $14,500 and a mean household size of 5 (SD=2). One-fourth of families were headed by mothers only and 71% by both a father and a mother. Initially, we recruited both mothers and fathers but fathers had a low rate of participation, likely because the procedures relied on parents’ attendance at school events (see Procedures). Mothers had an average of 9 years of school (SD=3.9) and fathers 8 years (SD=4.4). Only 10% of the mothers reported extended family members living with them (e.g., grandmothers, aunts). Mothers were predominantly immigrants (77% foreign and 23% U.S. born). Mothers reported having lived in this large city for 20 years (Median = 17, SD = 12.8; range 9 months to 47 years).

Procedures

Youth and their parents were recruited during school events (e.g. freshman orientation, back to school night). Informed consent and assent forms were given to parents and youth, respectively, in person. Participants were given the opportunity to complete questionnaires on site or at home (66% and 34%, respectively) and in their language of preference; 70% of youth and 26% of mothers completed in English. Bilingual research staff was available to answer questions on site. A toll free number was provided to participants to call for assistance on questionnaires completed at home. The majority of the participants did not have difficulty completing the questionnaires, although a few requested explanations and/or for questions to be read aloud to them. Bilingual research staff called participants who chose to answer questionnaires at home to remind them to return questionnaires and offer assistance. Youth and mothers were compensated for their participation, $10 and $20, respectively. Mothers were compensated more due to the longer time typically needed to complete the questionnaires relative to youth. Procedures and wording of consent forms were approved by a University Institutional Review Board and the high school’s school district for ethical treatment of participants and for description of research procedures at an appropriate grade level in both Spanish and English.

Measures

Youth substance use.

Youth substance use was measured with a composite variable of life-time alcohol, tobacco, and marijuana use. Composite variables of usage of these substances have been used by researchers (e.g., Martinez, 2006; Ostaszewski & Zimmerman, 2006; Walker-Barnes & Mason, 2004) because they are highly intercorrelated predictors of higher usage of illegal drugs (Kandel, Yamaguchi, & Chen, 1992) and substance misuse and abuse during late adolescence and young adulthood (Newcomb & Felix-Ortiz, 1992). We used the 2003 English version of the Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS) to assess lifetime substance use. The Spanish items were developed using back translation methods recommended in Foster and Martinez (1995).

Substance use was measured as a composite with the following questions: “During your life, on how many days have you had at least one drink of alcohol?”, “During your life, how many times have you used marijuana?”, and “Have you ever tried cigarette smoking, even one or two puffs?” Using the procedures suggested by Brener et al. (2004) we recoded the original response categories of alcohol and marijuana usage in the YRBS to form dichotomous response categories of lifetime use (0 = no use, and 1 = use).

We formed a substance use variable by adding the values of the three dichotomous substance variables: 0 = no life time usage of alcohol, marijuana, or tobacco (50% of the sample); 1= use of one substance (20%); 2 = use of two substances (20%), and 3 = use of all three substances (10%). All analyses were based on this composite index of substance use. Reported lifetime usage was 41% for alcohol, 37% for tobacco, and 16% for marijuana. These percentages were below the lower limit observed in state surveys of youth that used the YRBS in 2003: 43% to 81% ranges for alcohol, 33% to 71% for tobacco, and 21% to 49% for marijuana (Benbow, 2005). The results reported below are based on a single composite variable based on lifetime alcohol, tobacco, and marijuana. As expected the three variables were significantly intercorrelated (rs = .38 to .53, ps < .001).

Mother and youth linguistic/behavioral acculturation and enculturation.

The Bidimensional Acculturation Scale (BAS; Marin & Gamba, 1996) was used to measure behavioral/linguistic acculturation and enculturation among mothers and youth. Items measure language usage, linguistic proficiency, and language preference for media in English or American culture (acculturation) and in Spanish or Hispanic culture (enculturation) with 24 items for each culture. The scale was validated by the scale developers with a sample of 254 Mexican and Central American adults (74% completed the questionnaire in Spanish). Cronbach’s (α) for the Hispanicism (enculturation) and Americanism (acculturation) scales in our sample ranged between .84 and .96 for English- and Spanish-speaking youth and mothers. The possible range for the scales was 1 to 4.

Inner-city stressors.

We used the Multicultural Events Scale for Adolescents (MESA; Program for Prevention Research, n.d.; Gonzales, Tien, Sandler, & Friedman, 2001). Youth reported whether they have experienced the event within the last three months. We used English and Spanish versions created by the original developers. The violence exposure subscale included 10 items such as “You heard gunshots in your neighborhood.” The economic hassles subscale included 10 items such as “Your parent lost a job.” Positive responses were summed to form a total score of violence exposure and of economic hassle life events experienced by youth (the total scores can range from 1 to 10 for both scales).

Because the measure is a life events scale, internal consistency is not an applicable measure of reliability (Roosa, et al., 2005; Sandler & Guenther, 1984). Test-retest correlations for a two-week interval showed adequate reliability for the complete MESA (r = .71; Prevention Research Center, n.d.). The developers of the scale established concurrent validity. Scores on the MESA were positively associated with youth internalizing (e.g., anxiety, depression) and externalizing (e.g., delinquency, aggression; Barrera et al., 2002). The association between stressors and youth internalizing and externalizing has been found in numerous studies using other measures of stressors (e.g., Bailey, Hannigan, Delaney-Black, Covington, & Sokol, 2006; Gorman-Smith, Henry, & Tolan, 2004).

Family relationships.

Family cohesion.

Youth completed the cohesion subscale of the Family Environment Scales (FES; Moos & Moos, 1986). The subscale consists of nine true-false items that measure perceptions of family unity, commitment, help, and support such as “Family members really help and support one another”. Empirical results support the validity of the FES cohesion scale among Latino samples (see Santisteban et al., 2003). The scale has been found to be associated with depression and anxiety (e.g., Weisman, Rosales, Kymalainen, & Armest, 2005), substance use (Godley, Kahn, Dennis, Godley, & Funk, 2005), and alcohol (Kliewer et al., 2006) among Latinos. In the present study α =.66 for both English-speaking and Spanish-speaking youth. Scores can range from 0 to 9.

Parental monitoring.

We used Barrera et al.’s (2002) adapted version of the parental monitoring questionnaire (Small & Kerns, 1993; Small & Luster, 1994). The scale included items such as “When I went out, my mother knew where I was.” Higher scores indicate higher levels of youth perceptions of maternal monitoring. In the present study α=.95 for English-speaking respondents and α=.90 for Spanish-speaking youth. Scores can range from 1 to 5.

Results

Bivariate Correlations

Neither mother nor youth acculturation or enculturation were significantly associated with substance use (see Table 1). Violence exposure was associated with higher substance use but economic hassles were not. Family cohesion and parental monitoring were negatively related to substance use. Gender was significantly related to violence exposure and approached significance with maternal monitoring (male youth reported higher exposure to violence, and female youth reported higher levels of maternal monitoring). However, gender was not related to substance use. Therefore, it is an unlikely confound of associations between substance use and both family relationships and inner-city stressors.

Table 1.

Zero-order correlations and descriptive statistics of focal variables and gender

| Substance Use |

Gender |

Acculturation/Enculturation | Stressors | Family Relations | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Y. Enc. | Y. Acc. | M. Enc. | M. Acc. | Violence | Ec. Has. | Cohesion | Monitor. | |||

| Youth Substance Use | - | |||||||||

| Youth Gender | −.08 | - | ||||||||

| Youth Enculturation | .02 | .17† | - | |||||||

| Youth Acculturation | .08 | .03 | −.56** | - | ||||||

| Mom Enculturation | .14 | .10 | .40** | −.20† | - | |||||

| Mom Acculturation | .08 | −.15 | −.58** | .51** | −.46** | - | ||||

| Violence Exposure | .40** | −.22* | −.22* | .12 | .01 | .27** | - | |||

| Economic Hassles | .16 | −.12 | −.21* | .08 | −.27** | .16 | .34** | - | ||

| Family Cohesion | −.34** | .09 | .12 | −.05 | .05 | −.08 | −.38** | −.44** | - | |

| Maternal Monitoring | −.24* | .21† | −.13 | .25* | .07 | −.03 | −.09 | −.17 | .21† | - |

| Means | .91 | - | 2.78 | 3.32 | 3.19 | 2.43 | 1.81 | 1.18 | 5.74 | 4.07 |

| Standard Deviation | 1.07 | - | .77 | .62 | .71 | .94 | 2.05 | 1.45 | 2.16 | .78 |

| Observed Min. | 0 | - | 1.42 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2.09 |

| Observed Max. | 3.00 | - | 4.00 | 4.00 | 4.00 | 4.00 | 8.00 | 7.00 | 9.00 | 5.00 |

Note: Violence, Economic Hassles, Family cohesion and Maternal monitoring were youth reported. Gender was coded 0=male; 1=female

p < .05

p < .01

Parent-Youth Acculturation/Enculturation and Substance Use

To test if youth substance use was linked with youth-parent acculturation / enculturation, in hierarchical regression analyses we entered mother and youth acculturation and enculturation scores in the first block. No single variables were significantly associated with substance use (βs ≤ .23, ps ≥ .062) nor were they as a set [R2 = .05, F(4, 88) = 1.1, p = .33]. In the second block, we entered a mother acculturation by youth acculturation interaction term and a mother enculturation by youth enculturation interaction term (see Birman, 2006) using centered variables (Aiken & West, 1991). As a set, the dyadic interaction terms accounted for significant variance beyond the main effects of the mother and youth enculturation and acculturation scores [∆R2 = .10, F( 2, 86) 4.8, p = .01]. Both the acculturation interaction term (β = −.31, p= .01) and the enculturation interaction term (β = .31, p < .05) were significantly associated with substance use. In the model with interaction terms, mothers’ enculturation was significant (β = .28 p = .02). Mothers’ acculturation, youth enculturation, and youth acculturation were not significantly related to substance use (βs ≤ .24, ps ≥ .086).

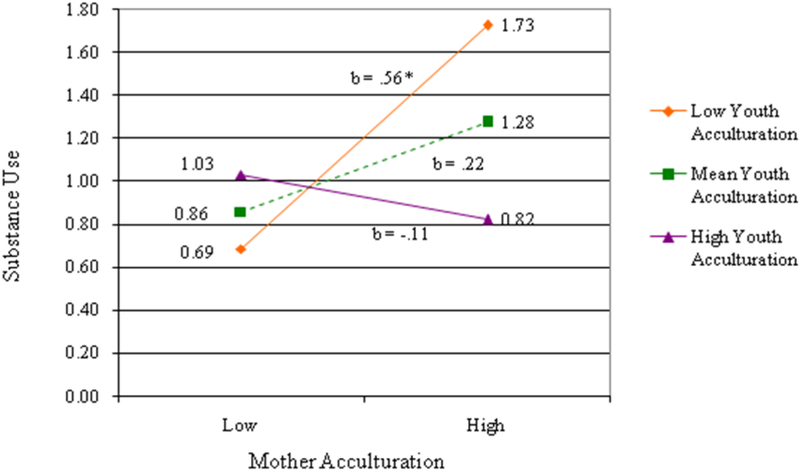

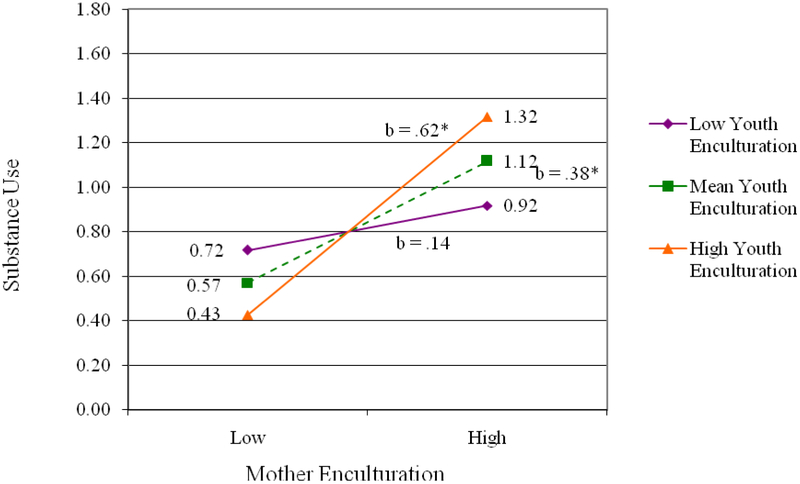

Following the recommendations of Cohen, Cohen, West, & Aiken (2003) and Holmbeck (2002), we calculated regression slopes to interpret the interactions. Figure 1 illustrates that as mothers’ acculturation increased, youth substance use also increased significantly but only when youth acculturation levels were low (relative to other youth in the sample). The relation between mothers’ acculturation levels and youth substance use was not significant at mean or at high youth acculturation. Figure 2 shows that when mother’s enculturation levels increased, youth substance use also increased when youth enculturation levels were high or at the mean, but not when youth enculturation was low (relative to other youth in the sample).

Figure 1.

Mother-youth acculturation and substance use interaction simple slopes.

Note. Graph lines are based on predicted values calculated via simple regression slopes procedures (see Cohen et al, 2003; Holmbeck, 2002)

* p < .05

Figure 2.

Mother-youth enculturation and substance use interaction simple slopes.

Note. Graph lines are based on predicted values calculated via simple regression slopes procedures (see Cohen et al, 2003; Holmbeck, 2002)

* p < .05

Multiple Regression of Substance Use with All Focal Variables

We conducted a multiple regression analysis with simultaneous entry of all focal variables (see Table 2). The model was significantly associated with substance use [R2 = .34, F (10, 82) = 4.3, p < .001]. Parent-youth acculturation and enculturation, mother enculturation, violence exposure, and family cohesion were uniquely and significantly related to substance use.

Table 2.

Regression model of substance use by family relationship, acculturation / enculturation and inner-city risk variables.

| Variable | B | b | SE |

|---|---|---|---|

| Family Cohesion | −.20* | −.10* | .05 |

| Maternal Monitoring | −.13 | −.18 | .13 |

| Mother Acculturation | .11 | .12 | .15 |

| Youth Acculturation | −.06 | −.11 | .21 |

| Mother Enculturation | .24* | .36* | .17 |

| Youth Enculturation | .13 | .18 | .18 |

| Mother X Youth Acculturation | −.27* | −.31* | .12 |

| Mother X Youth Enculturation | .33** | .25** | .09 |

| Violence exposure | .30** | .15** | .05 |

| Economic Hassles | .00 | .00 | .08 |

Note. β = Standardized regression coefficients. b=unstandardized regression coefficients. SE=Standard Errors of bs.

p ≤ .05

p < .01

Family relationships as mediators of mother-youth acculturation/enculturation.

Family cohesion and monitoring were tested as mediators of mother-youth acculturation, and mother-youth enculturation. Given that the latter two were interaction terms, we used an analytic framework to test for the mediation of a moderation effect (see Muller, Judd, and Yzerbyt, 2005). Notably, the framework integrates mediation theory criteria (Baron & Kenny, 1986). The analysis includes tests of whether the mediator (e.g., cohesion) is related to both the outcome (substance use) and the predictor (parent-youth acculturation), as well as the reduction of the predictor when the mediator is introduced. When the mediators were introduced (cohesion, monitoring) in separate tests, there were no substantial reductions in either the mother-youth acculturation or the mother-youth enculturation interaction term (reduction in βs <.03). Furthermore, the mediation analyses also tested whether the mother-youth acculturation and enculturation terms predicted family cohesion or maternal monitoring. These tests yielded null results (βs ≤ .09, ps > .43). Taken together, we found no support for mediation by family cohesion or maternal monitoring of the mother-youth acculturation and enculturation moderation effects on substance use (detailed results are available from the first author upon request).

Family relationships as mediators of inner-city stressors.

To assess whether family relationships mediate the link between violence and substance use, we performed the Sobel Test (Sobel, 1982) with formulas by Preacher and Leonardelli (2003) to test whether a mediator has a statistically significant indirect effect (i.e., it accounts for a substantial portion of the effect of an independent variable on the outcome). Monitoring was not a significant mediator (Sobel Test = 0.7, p = .48). However, family cohesion was a significant mediator (Sobel Test = 1.8, p = .05). We estimated the substance use variance mediated by cohesion following Cohen et al. (2003). Violence exposure explained 15% of the variance of substance use (r2 = .15). When family cohesion was partialled out, violence explained 9% of the variance (sr2 subs use and violence, partialling family cohesion = .09). Thus, only 6% of 9% the variance was explained away by family cohesion, suggesting partial mediation.

Discussion

Family cohesion was substantially related to lower substance use in our sample of Mexican American youth and mother dyads. This is consistent with past empirical studies that used prospective and/or intervention designs (Santisteban et al., 2003; Szapocznik et al., 2007). Furthermore, our findings are consistent with family interaction theory which posits that family cohesion reduces the likelihood that youth become involved with substance using peers, increases youth acceptance of parental values, and promotes emotional security (see Pertraitis et al., 2005; Brook, Brook, Gordon, Whiteman, & Cohen, 1990). The influence of family cohesion has been replicated in other studies with Latino youth (Gil et al., 2000; Santisteban et al. 2003). Thus the hypothesized mechanisms posited by family interaction theory (e.g., reduced negative peer influence) deserve empirical examination in research with this population.

Both mother-youth acculturation and mother-youth enculturation were significantly related to youth substance use. The findings are consistent with past results highlighting the importance of acculturation at the parent-youth dyad level in the risk for substance use among Latino youth (Szapocznik & Kurtines, 1980; Martinez, 2006). However, we did not find support for family relationships mediating the link between mother-youth acculturation and substance use, nor did we find support for the pattern of high youth acculturation and mother low acculturation as a risk factor.

It is possible that family relationship variables such as cohesion are more likely to mediate cultural values or other aspects of cultural participation than linguistic/behavioral acculturation. However, other researchers have empirically observed links between youth substance use and parent-youth acculturation using linguistic/behavioral measures (e.g., Szapocznik & Kurtines, 1980; Martinez, 2006). Of these, Martinez (2006) found evidence in favor of mediation by family variables of the link between behavioral acculturation gaps and substance use. Thus, we think that it is unlikely that the lack of mediation by cohesion or monitoring can be accounted for entirely by the linguistic/behavioral operationalization of acculturation and enculturation.

We posit two additional reasons (which we do not see as mutually exclusive) for the lack of family mediation in our study. First, our sample consisted of mother-youth dyads that were recruited at school events such as orientations and back to school nights. Thus, the sample may under-represent mother-youth dyads with severe substance use and family problems. In fact, students’ reported substance use levels were low compared to results in other studies using the Youth Risk Behavior Survey. In contrast to the present study, early support for the gap distress theory emerged from clinical observations of Cuban American youth and their families receiving treatment for substance use problems (Szapocznik & Kurtines, 1993). It is possible that with more severe youth problem behaviors a transactional process emerges involving low family cohesion, youth-parent acculturation gaps, and severe youth problem behaviors such as substance use (see Szapocznik & Kurtines, 1980). It is possible that such processes were present in our sample because severe cases of substance use were likely underrepresented.

A second possible explanation for the lack of family relationship mediation is the setting of our study which is an ethnic enclave with a high population density of Latinos (predominantly of Mexican descent). In contrast, Martinez (2006) found evidence for the acculturation gap distress theory in a sample of predominantly Mexican American youth and families from a community with a low population density of Latinos in Oregon. Although not identical to ours, Martinez (2006) also used a behavioral measure of acculturation and found that family relationships mediated acculturation gaps and substance use. It could be that in communities with high Latino density, there are more opportunities for youth to be socialized to participate in both cultures (e.g., through school and community events). In contrast, in communities with low Latino population density, the imbalance of promotion of participation in culture of origin (primarily promoted at home) and in the new culture (primarily promoted at school) may be particularly germane for the rise of parent-youth acculturation gaps.

Simple slope probing (Cohen et al., 2003; Holmbeck, 2002) of mother-youth acculturation showed that higher levels of mother acculturation (relative to other mothers in the sample) were related to higher substance use but only when levels of youth acculturation were low (relative to other youth in the sample). Birnam (2006) and Lau et al. (2005) empirically observed links between poor mental health among immigrant youth and high mother acculturation-low youth acculturation. Together their findings and ours raise the possibility that high parental acculturation may represent a risk factor for youth mental health in the context of low youth acculturation.

We posit that social attachment theory is a viable explanation for our findings. According to social attachment theories, substance use is likely to increase when youth have “weak conventional bonds to society and institutions” (Pertraitis et al., 1995, p. 71). Accordingly, youth with low acculturation are likely to have such weak conventional bonds to institutions in the U.S. such as school as well as poorly formed peer relationships. In these situations, youth may pursue gang membership to build their ethnic identity and self-esteem. The scenario of weak bonds with institutions is worsened when low acculturation youth also have gaps in acculturation with their mothers who are higher in acculturation (and possibly weak bonds with their caretakers as well). Furthermore, high acculturation mothers might be more likely to use alcohol and tobacco than lower acculturation mothers and thus inadvertently role model the use of these substances.

In this study we examined acculturation and enculturation as separate dimensions, which is desirable because high acculturation may coexist with high enculturation as well (Gonzales et al., 2002). However, measurement of enculturation is atypical in Latino youth substance use literature. We found that when youth levels of enculturation were high and at the mean (relative to other youth in the sample), higher levels of mother’s enculturation (relative to other mothers in the sample) were related to higher youth substance use. This is an unexpected finding given that the results do not point to cultural gap but rather to the combination of high enculturation. Perhaps there are stressors related to recent high youth and mother enculturation (e.g., family stressors tied to recent immigration such as social isolation) which together produce a cumulative impact on substance use risk (Vega & Gil, 1999; Pertraitis et al., 1995).

Violence exposure was a robust correlate of substance use. This is a significant finding given that many Latino youth live in inner-city settings with high levels of violence and gang-related activity (Gonzales et al., 2002). Following ecological models of substance use (Martinez et al., 2003; Vega & Gil, 1999), inner-city stressors such as violence undermine the protective role of the family, resulting in increased risk for substance use. Consistent with this hypothesis, we found significant mediation by family cohesion of the link between violence and substance use. In a separate study with Mexican American families in this neighborhood, parents have reported high involvement with their youth, partly as a strategy to minimize the time that their adolescent children spend in the streets potentially exposed to, or involved with, gangs (Cruz-Santiago & Ramírez García, n.d.). It is possible that families perceived as cohesive by youth are also effective in minimizing the exposure to violence by youth. Researchers working in inner-city settings have also found that family cohesion is related to low exposure to violence (Gorman-Smith, Henry, & Tolan, 2004).

It is worth noting that violence had a unique and significant association with substance use even after family cohesion was partialled out. Kliewer et al. (2006) also found that family cohesion and violence both had unique and significant associations with youth illicit drug use in Central America. Our results along with those of Kliewer et al. (2006) highlight that violence exposure may impact substance use through family cohesion as well as through other processes. It is possible that higher levels of violence exposure are related to higher levels of availability of alcohol and/or marijuana available to youth (see Kliewer et al. 2006; Vega & Gil, 1999). For example, youth who witness violence are likely to have alcohol and other substances available to them because high gang activity is associated with both neighborhood violence and availability of substances (Walker-Barnes & Mason, 2004). Availability of drugs and affiliation with substance using peers are robust predictors of substance use among youth (Oetting & Beauvais, 1986; Pertraitis et al., 1995).

Researchers have found that when social disorganization in neighborhoods reaches high levels, family relationships are no longer related to the levels of violence exposure by youth (Sheidow, Gorman-Smith, Tolan, & Henry, 2001). In light of this empirical evidence, researchers should consider the limitations of family processes to buffer against contextual risk factors such as sheer drug use availability. In the words of Vega and Gil (1999), “as the family is exposed to the cumulative conditions of disorganized inner-city barrios [neighborhoods], it is evident that preventive interventions that rely solely on family dynamics will prove to be inadequate and ineffective at a population level” (p. 65).

Caveats and Research Directions

We measured substance use with the YRBS, a self-report national surveillance measure (Brenner et al., 2004) and found that student’s reports of substances were low compared to national YRBS reports. We cannot rule out methodological explanations for low reports of usage including retrospective self-report, the nearby presence of mothers, and cross-cultural measurement non-equivalence. However, it is also likely that the reported low rates reflect an underrepresentation of youth with higher usage levels because they (and their parents) might have been less likely to participate in this study which relied on voluntary participation at school events. Thus the findings reported here may apply particularly to youth and families with moderate to low levels of substance use. Notably, we did not measure mother substance use per se which is likely to influence youth substance use; we recommend researchers to integrate parental substance use in Latino youth substance use research. The neighborhood should be taken into account along with the national origin of our sample in the interpretation of these results. Our findings might be more generalizable to immigrants, irrespective of national origin, who live in inner-city settings than to Mexican Americans who live in contrasting settings. Inner-city stressors and their link to cultural participation are likely to impact family processes and youth mental health (see Vega & Gil, 1998, 1999; Berry, 1997). Future studies with diverse Latino populations across diverse settings are needed to shed light on the generalizability of our parent-youth acculturation findings.

It is also crucial to interpret the mother-youth acculturation and enculturation findings in light of our linguistic/behavioral measures. Although our measures have excellent psychometric properties and yielded a wider range of variance than proxies such as nativity, future research should also examine how specific processes tied to these linguistic proxies of cultural participation impact substance use. We used a moderation (variable interaction) approach to examine mother-youth acculturation / enculturation rather than forming groups of dyads based on a priori defined cut-offs of acculturation / enculturation (see Birnam, 2006). Unlike other data analytic strategies, the moderation approach did not limit us to testing only those patterns predicted to be risk factors by acculturation- gap theory. Nonetheless, the results suggest that some groups of dyads (e.g., high acculturation mothers/low acculturation youth) might yield higher or lower risk in substance use than others. Although our study is unique in that we measured both youth and parental acculturation/enculturation, we did not collect data from fathers. Thus our findings are constrained to maternal acculturation / enculturation (and maternal youth monitoring). Likewise, we urge researchers to also parental substance use and their attitudes and values regarding substance use that they promote to their adolescent children.

Cross-cultural measurement equivalence data were not available for the measures that we used; error introduced by language might have impacted our results to an unknown degree. However, we believe that such error is more likely to underestimate rather than over-estimate the reported relations between variables and thus the significant findings are unlikely to be misleading. In fact two of the major correlates of substance use in this study (family cohesion and exposure to violence) have been reported in prior studies as well. Because our data are cross-sectional, we cannot infer that either acculturation/enculturation or violence exposure predict substance use; accordingly we do not emphasize this specific direction of influence in the interpretation of the findings. Family systemic paradigms, which emphasize bi-directional influence between family processes and youth substance use (Santisteban et al., 2003; Szapocznik, Hervis, & Schwartz, 2003) are most useful to interpret these data and to advance inquiry in this scarce body of research.

Acknowledgments

This research and manuscript preparation were supported by an Arnold O. Beckman award by the University of Illinois and by a Visiting Scholar Fellowship by the Center for Latino Family Research, Washington University in St. Louis, awarded to Ramírez García, as well as by an American Psychological Association (APA) Minority Fellowship Program (NIMH Training Grant MH15742-26) awarded to Cruz-Santiago. Special thanks to Howard Berenbaum for his valuable input on previous drafts as well as to Juan Peña. We are very grateful to the mothers and youth who participated and to Dr. Richard Gelb, Principal Natividad Loredo, and the school staff who welcomed our research team.

References

- Aiken LS, & West SG (1991). Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Newbury Park, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Amaro H, Whitaker R, Coffman G, & Heren T (1990). Acculturation and marijuana and cocaine use: Findings from HHANES 1982-1984. American Journal of Public Health, 80, 54–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apospori EA, Vega WA, Zimmerman RS, Warheit GJ, & Gil AG (1995). A longitudinal study of the conditional effects of deviant behavior on drug use among three racial/ethnic groups of adolescents In Kaplan HB (Ed.), Drugs, crime, and other deviant adaptations: Longitudinal studies (pp. 211–230). New York: Plenum Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bailey BN, Hannigan JH, Delany-Black V, Covington C & Sokol RJ (2006). The role of maternal acceptance in the relation between community violence exposure and child functioning. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 34, 57–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron RM, & Kenny DA (1986). The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51, 1173–1182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrera M, Prelow HM, Dumka LE, Gonzales NA, Knight GP, Michaels ML et al. (2002). Pathways from family economic conditions to adolescents’ distress: Supportive parenting, stressors outside the family, and deviant peers. Journal of Community Psychology, 30, 135–152. [Google Scholar]

- Benbow N (2005). 2003 Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS): Summary of Results form A Representative Sample of Students From Selected Chicago Public High Schools.

- Board of Education of the City of Chicago. Chicago, IL: Retrieved [2/December/10] from http://www.oism.cps.k12.il.us/pdf/2003YRBS.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Berry JW (1997). Immigration, acculturation, and adaptation. Applied Psychology: An International Review, 46, 5–68. [Google Scholar]

- Birman D (2006). Acculturation gap and family adjustment findings with Soviet Jewish refugees in the United States and implications for measurement. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 37, 568–589. [Google Scholar]

- Brener ND, Kann L, Kinchen SA, Grunbaum JA, Whalen L, Eaton D, Hawkins J, & James G Ross JG (2004). Methodology of the Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System (MMWR 2004-053 No. RR-12). Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; Atlanta, GA: Retrieved [12/December/08] from http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/rr5312a1.htm [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brook JS, Brook DW, Gordon AS, Whiteman M, & Cohen P (1990). The psychosocial etiology of adolescent drug use: A family interactional approach. Genetic, Social & General Psychology Monographs, 116, 111–267. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J, Cohen P, West SG, & Aiken LS (2003). Applied multiple regression/correlation analyses for the behavioral sciences (3rd Ed.). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- Cruz-Santiago M & Ramírez García J (n.d.). “Hay que ponerse en los zapatos del joven”: Adaptive parenting of adolescent children among Mexican-American parents residing in a dangerous neighborhood. Manuscript under review. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Foster SL, & Martinez CM Jr. (1995). Ethnicity: Conceptual and methodological issues in child clinical research. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 24, 214–226. [Google Scholar]

- Gil AG, Wagner EF, & Vega WA (2000). Acculturation, familism and alcohol use Among Latino adolescent males: Longitudinal relations. Journal of Community Psychology, 28, 443–458. [Google Scholar]

- Great Cities Institute. (n.d.). Neighborhood Initiative: Pilsen (Lower West). Retrieved [2/December/10] from http://www.uicni.org/page.php?section=neighborhoods&subsection=pilsen

- Gorman-Smith D, Henry DB, & Tolan P (2004). Exposure to community violence and violence penetration: The protective effects of family functioning. (2004). Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 33, 439–449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godley MD, Kahn JH, Dennis ML, Godley SH, & Funk RR (2005). The stability and impact of environmental factors on substance use and problems after adolescent outpatient treatment for cannabis abuse or dependence. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 19, 62–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzales NA, Knight GP, Morgan-Lopez AA, Saenz D, & Sirolli A (2002). Acculturation and the mental health of Latino youths: An integration and critique of the literature In Contreras JM, Kerns KA, & Neal-Barnett AM (Eds.), Latino children and families in the United States: Current research and future directions (pp. 45–74). Westport, CT: Praeger. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzales NA, Tein JY, Sandler IN, & Friedman R (2001). On the limits of coping: Interaction between stress and coping for inner-city adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Research, 16, 372–395. [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Stinson FS, Hasin DS Dawson DA, Chou SP, & Anderson K (2004). Immigration and lifetime prevalence of DSM-IV psychiatric disorders among Mexican American and Non-Hispanic Whites in the Unites States. Results from the National Epidemiological Survey on alcohol and related conditions. Archives of General Psychiatry, 61, 1226–1233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins JD, Catalano RE, & Miller JY (1992). Risk and protective factors for alcohol and other drug problems in adolescence and early adulthood: Implications for substance abuse prevention. Psychological Bulletin, 112, 64–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmbeck GN (2002). Post-hoc probing of significant moderational and mediational effects in studies of pediatric populations. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 27(1), 5–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kandel D, Yamaguchi K, & Chen K (1992). Stages of progression in drug involvement from adolescence to adulthood: Further evidence for the gateway theory. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 53, 447–457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kliewer W, Murrelle L, Prom E, Ramirez M, Obando P, Sandi L, et al. (2006). Violence exposure and drug use in Central American youth: Family cohesion and parental monitoring as protective factors. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 16, 455–478. [Google Scholar]

- Laird J, Cataldi EF, KewalRamani A, & Chapman C (2008). Dropout and Completion Rates in the United States: 2006 (NCES 2008-053). National Center for Education Statistics, Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education; Washington, DC: Retrieved [12/December/08] from http://nces.ed.gov/pubsearch/pubsinfo.asp?pubid=2008053 [Google Scholar]

- Lau AS, McCabe KM, Yeh M, Garland AF, Wood PA, & Hough RL (2005). The acculturation gap-distress hypothesis among high- risk Mexican American families. Journal of Family Psychology, 19, 367–375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marin G, & Gamba R (1996). A new measurement of acculturation for Hispanics: the bidimensional acculturation scale for Hispanics (BAS). Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 18, 297–316. [Google Scholar]

- Martinez CR, Eddy JM, & DeGarmo DS (2003). Preventing substance use among Latino youth In Bukoski WJ & Sloboda Z (Eds.), Handbook of drug abuse prevention: Theory, science, and practice (pp. 365–380). New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum. [Google Scholar]

- Martinez CR (2006). Effects of differential family acculturation on Latino adolescent substance use. Family Relations, 55, 306–317. [Google Scholar]

- Muller D Judd CM, & Yzerbyt VY (2005). When moderation is mediated and mediation is moderated. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 89, 852–863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moos RH & Moos BS (1986). Family Environment Scale Manual. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press. [Google Scholar]

- Newcomb DN, & Felix-Ortiz M (1992). Multiple protective and risk factors for drug use and abuse: Cross-sectional and prospective findings. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 63, 280–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oetting ER & Beauvais F (1986). Peer cluster theory: Drugs and the adolescent. Journal of Counseling & Development, 65, 17–22. [Google Scholar]

- Ostaszewski K & Zimmerman MA (2006). The effects of cumulative risks and protective factors on urban adolescent alcohol and other drug use: A longitudinal study of resiliency. American Journal of Community Psychology, 38, 237–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pertraitis J, Flay BR, & Miller TQ (1995). Reviewing theories of adolescent substance use: Organizing pieces in the puzzle. Psychological Bulletin, 117, 67–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, & Leonardelli GJ (2003). Calculation for the Sobel Test: An interactive calculation tool for mediation tests. [Data file]. Retrieved from http://people.ku.edu/~preacher/sobel/sobel.htm

- Program for Prevention Research. (n.d.) Manual for the Multicultural Events Schedule for Adolescents (MESA). Tempe, Arizona: Arizona State University; Retrieved [12/May/2008] from http://www.asu.edu/clas/asuprc/pdf/MESA%20Manual.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Roosa MW, Deng S, Ryu E, Burrell GL, Tein J-Y, Jones S, et al. (2005). Family and child characteristics linking neighborhood context and child externalizing behavior. Journal of Marriage and Family, 67, 515–529. [Google Scholar]

- Sandler I, & Guenther R (1984). Assessment of life stress events In Karoly P (Ed.), Measurement strategies in health psychology (pp. 555–600). New York: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Santisteban DA., Coatsworth JD, Perez-Vidal A, Kurtines WM, Schwartz SJ, LaPerriere A, & Szapocznik J (2003). Efficacy of Brief Strategic Family Therapy in modifying Hispanic adolescent behavior problems and substance use. Journal of Family Psychology, 17, 121–133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheidow AJ, Gorman-Smith D, Tolan PH, Henry DB (2001). Family and community characteristics: Risk factors for violence exposure in inner-city youth. Journal of Community Psychology, 29, 345–360. [Google Scholar]

- Small SA & Kerns D (1993). Unwanted sexual activity among peers during early and middle adolescence: Incidence and risk factors. Journal of Marriage & the Family, 55, 941–952. [Google Scholar]

- Small SA & Luster T (1994). Adolescent sexual activity: An ecological, risk-factor approach. Journal of Marriage & the Family, 56, 181–192. [Google Scholar]

- Sobel ME (1982). Asymptotic intervals for indirect effects in structural equations models In Leinhart S (Ed.), Sociological Methodology 1982 (pp. 290–312). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Szapocznik J & Coatsworth JD (1999). An ecodevelopmental framework for organizing the influences on drug abuse: a developmental model of risk and protection In Glantz M & Hartel C (Eds.) Drug Abuse: Origins and Interventions. (pp. 331–66).Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Szapocznik J, & Kurtines WM (1980). Acculturation, biculturalism, and adjustment among Cuban Americans In Padilla A (Ed.), Recent advances in acculturation research: Theory, models and some new findings (pp. 139–157). Boulder, CO: Westview. [Google Scholar]

- Szapocznik J, & Kurtines WM (1993). Family psychology and cultural diversity: Opportunities for theory, research, and application. American Psychologist, 48, 400–407. [Google Scholar]

- Szapocznik J, Prado G, Burlew KA, Williams RA, & Santisteban DA (2007). Drug abuse in African American and Hispanic adolescents: Culture, development and behavior. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 3, 77–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau. (2000). Fact Sheet for Zip Code 60608. Retrieved [2/December/10] from http://factfinder.census.gov

- Vega WA, & Gil AG (1998). Drug use and ethnicity in early adolescence. New York, NY: Plenum Press. [Google Scholar]

- Vega WA, & Gil AG (1999). A model for explaining drug use behavior among Hispanic adolescents. Drugs & Society, 14, 57–74. [Google Scholar]

- Vega WA, Gil AG, Warheit GJ, Zimmerman RS, & Apospori E (1993). Acculturation and delinquent behavior among Cuban American adolescents: Toward and empirical model. The American Journal of Community Psychology, 21, 113–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vega WA, Sribney WM, & Achara-Abrahams I (2003). Co-occurring alcohol, drug, and other psychiatric disorders among Mexican-origin people in the United States. American Journal of Public Health, 93,, 1057–1064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker-Barnes CJ & Mason CA (2004). Delinquency and substance use among gang involved youth: The moderating role of parenting practices. American Journal of Community Psychology, 34, 235–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisman A, Rosales G, Kymalainen J, & Armesto J (2005). Ethnicity, family cohesion, religiosity and general emotional distress in patients with schizophrenia and their relatives. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 193, 359–368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]