Abstract

Purpose

To report the outcomes of sinonasal tumors treated with proton beam therapy (PBT) on the Proton Collaborative Group registry study.

Methods and Materials

Sixty-nine patients with sinonasal tumors underwent curative intent PBT between 2010 and 2016. Patients who received de novo irradiation (42 patients) were analyzed separately from those who received reirradiation (27 patients) (re-RT). Median age was 53.1 years (range, 15.7-82.1; de novo) and 57.4 years (range, 31.3-88.0; re-RT). The most common histology was squamous cell carcinoma in both groups. Median PBT dose was 58.5 Gy (RBE) (range, 12-78.3; de novo) and 60.0 Gy (RBE) (range 18.2-72.3; re-RT), and median dose per fraction was 2.0 Gy (RBE) for both cohorts. Survival estimates for patients who received de novo irradiation and those who received re-RT were calculated using the Kaplan-Meier method.

Results

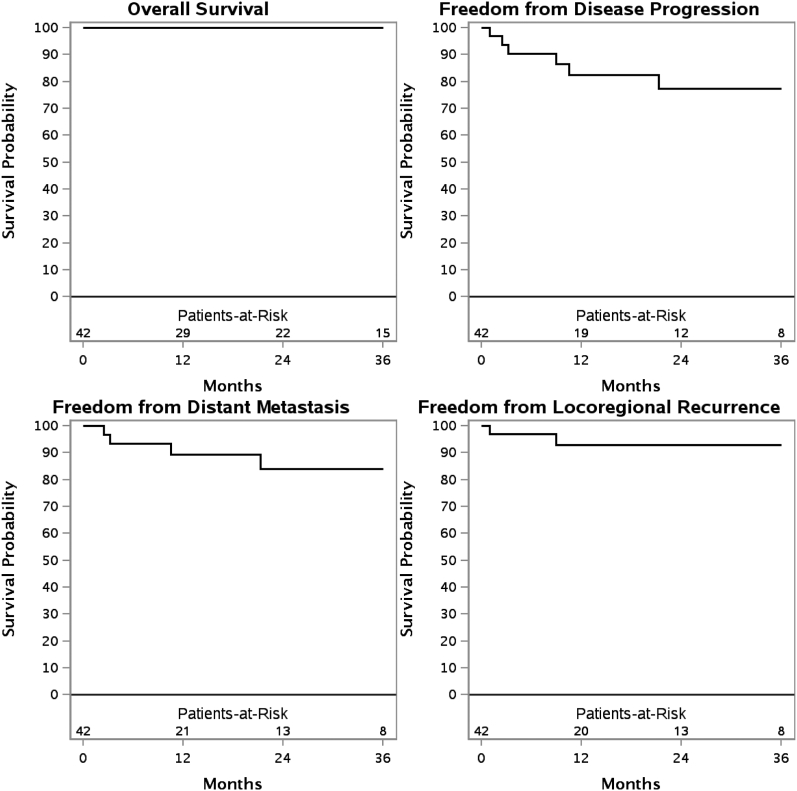

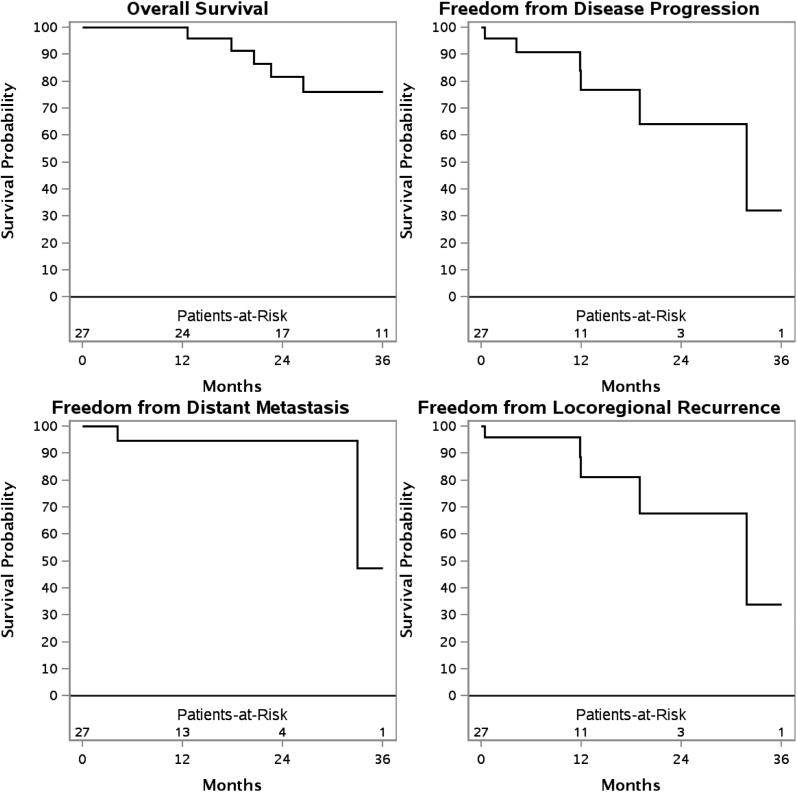

Median follow-up for surviving patients was 26.4 months (range, 3.5-220.5). The 3-year overall survival (OS), freedom from distant metastasis, freedom from disease progression, and freedom from locoregional recurrence (FFLR) for de novo irradiation were 100%, 84.0%, 77.3%, and 92.9%, respectively. With re-RT, the 3-year OS, freedom from distant metastasis, FFDP, and FFLR were 76.2%, 47.4%, 32.1%, and 33.8%, respectively. In addition, 12 patients (17.4%) experienced recurrent disease. Re-RT was associated with inferior FFLR (P = .04). On univariate analysis, squamous cell carcinoma was associated with inferior OS (P < .01) for patients receiving re-RT. There were 11 patients with acute grade 3 toxicities. Late toxicities occurred in 15% of patients, with no grade ≥3 toxicities. No patients developed vision loss or symptomatic brain necrosis.

Conclusions

As one of the largest studies of sinonasal tumors treated with PBT, our findings suggest that PBT may be a safe and efficacious treatment option for patients with sinonasal tumors.

Summary.

Proton beam therapy is a promising treatment option for sinonasal tumors. We report the outcomes of 69 patients with sinonasal tumors treated with proton beam therapy on the multi-institutional Proton Collaborative Group registry study. This is one of the largest series of sinonasal tumors treated with proton beam therapy. Our findings suggest that proton beam therapy is a safe and efficacious treatment option for patients with sinonasal tumors.

Introduction

Sinonasal tumors originate from the nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses. The incidence of sinonasal tumors is 0.556 cases per 100,000 population per year, and they often occur in the sixth decade of life with a male predominance of 1.8:1.1 Overall, they represent approximately 3% to 5% of all head and neck cancers.2 Sinonasal tumors are a heterogenous group of histologic subtypes, including squamous cell carcinoma (most common), adenocarcinoma, adenoid cystic carcinoma, melanoma, esthesioneuroblastoma, and undifferentiated carcinoma.3 Diagnosis of sinonasal tumors is complex; it is often delayed owing to a lack of specific clinical symptoms. Thus, sinonasal tumors often present as locally advanced disease with extensive invasion into adjacent normal structures. In these patients, identifying the site of origin can be challenging.2

Because sinonasal tumors are rare, there have been no randomized clinical trials to guide treatment recommendations. Current treatment recommendations are based on retrospective, single-institution experiences.4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10 These studies often include various primary sites, histologic subtypes, and surgical approaches. The heterogeneity of sinonasal malignancies and multiple treatment approaches make it challenging to draw conclusions regarding treatment outcomes.

Achieving local control in sinonasal tumors is both critical and challenging owing to their intimate anatomic relationship with many vital structures such as the brainstem, brain, optic tracts, and eyes.11 In general, the less common presentation of early stage sinonasal tumors is managed with surgery alone. Locally advanced sinonasal tumors are most commonly managed with multimodality therapy including surgery, radiation therapy (RT), or chemotherapy.12 In addition, RT can be used as a definitive treatment for patients with unresectable disease or who are otherwise nonsurgical candidates. Historically, treatment outcomes for sinonasal tumors have been poor, with 5-year overall survival rates in the range of 22% to 79%12 and local control (LC) rates of 40% to 60%.5, 8, 9, 13 With the advent of modern radiation techniques such as intensity-modulated radiation therapy (IMRT) and charged particle therapy, improved outcomes can potentially be achieved in sinonasal tumors.13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19

One of the limitations of conventional photon radiation therapy is the limited ability to safely deliver adequate dose to the primary target without compromising surrounding healthy structures.15, 16, 19 Charged particle therapy in the form of proton beam therapy (PBT) has clear dosimetric advantages over conventional photon RT. This includes a rapid fall-off dose beyond the Bragg peak and a higher relative biologic effectiveness; these advantages allow the treating radiation oncologist to escalate dose to the primary target and maximally spare adjacent healthy structures.19 The theoretical advantages of PBT have been suggested to be associated with better outcomes in patients with sinonasal tumors compared with patients treated with conventional photon therapy.16, 20 In a meta-analysis of nasal cavity and paranasal sinus tumors treated with radiation therapy, Patel et al reported significantly improved locoregional control for PBT than for IMRT.16 There is a need to report more outcomes associated with PBT for sinonasal tumors because most reports are smaller series from single institutions. The aim of our study is to report the outcomes of patients with sinonasal tumors treated with PBT in the multi-institutional Proton Collaborative Group (PCG) registry study.

Methods and Materials

The PCG is a nonprofit organization of radiation oncologists including 10 institutions with PBT and 12 treatment sites. Participating institutions for this study include the Northwestern Medicine Chicago Proton Center, ProCure Proton Therapy Center New Jersey, ProCure Proton Therapy Center Oklahoma City, Seattle Cancer Care Alliance Proton Therapy Center, University of Maryland Proton Treatment Center, California Protons Cancer Therapy Center, and Willis-Knighton Cancer Center. This study is an institutional review board–approved analysis of the multi-institutional PCG data registry of patients treated with PBT. Between 2010 and 2016, 69 patients with sinonasal tumors were treated with curative intent PBT on the PCG registry study. Patient demographics and characteristics are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Patient and treatment characteristics (n = 69)

| Characteristic | De novo irradiation (n = 42) no. patients (%) | Reirradiation (n = 27) no. patients (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (y) | ||

| Median | 55.9 | 58.1 |

| Range | 15.7-82.1 | 31.3-88.0 |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 29 (69.0%) | 17 (63.9%) |

| Female | 13 (31.0%) | 10 (37.0%) |

| ECOG PS | ||

| 0 | 30 (71.4%) | 19 (70.4%) |

| ≥1 | 12 (28.6%) | 8 (29.6%) |

| Smoking status | ||

| Nonsmoker | 26 (64.3%) | 14 (51.9%) |

| Former/current smoker | 15 (35.7%) | 13 (48.1%) |

| Primary site | ||

| Nasal cavity | 21 (55.3%) | 14 (60.9%) |

| Maxillary sinus | 10 (26.3%) | 5 (21.7%) |

| Ethmoid sinus | 7 (18.4%) | 3 (13.0%) |

| Sphenoid sinus | 0 | 1 (4.3%) |

| Not specified | 4 | 4 |

| Histology | ||

| Squamous cell carcinoma | 15 (35.7%) | 11 (40.7%) |

| Adenoid cystic carcinoma | 8 (19.0%) | 6 (22.2%) |

| Esthesioneuroblastoma | 10 (23.8%) | 4 (14.8%) |

| Adenocarcinoma | 5 (11.9%) | 4 (14.8%) |

| Small cell neuroendocrine | 2 (4.8%) | 1 (3.7%) |

| SNUC | 2 (4.8%) | 1 (3.7%) |

| T stage | ||

| T1 | 5 (11.9%) | 0 |

| T2 | 6 (14.3%) | 3 (11.1%) |

| T3 | 6 (14.3%) | 7 (25.9%) |

| T4a | 7 (16.7%) | 9 (33.3%) |

| T4b | 18 (42.9%) | 8 (29.6%) |

| N stage | ||

| N0 | 37 (88.1%) | 19 (70.4%) |

| N1-N2 | 5 (11.9%) | 8 (29.6%) |

| Stage | ||

| I | 5 (11.9%) | 0 |

| II | 6 (14.3%) | 2 (7.4%) |

| III | 6 (14.3%) | 6 (22.2%) |

| IVA | 7 (16.7%) | 11 (40.7%) |

| IVB | 16 (38.1%) | 8 (29.6%) |

| IVC | 2 (4.8%) | 0 |

| Proton beam therapy target | ||

| Primary site/surgical bed | 39 (92.9%) | 23 (92.0%) |

| Primary site + neck | 2 (4.8%) | 2 (8.0%) |

| Not specified | 1 | 2 |

| Concurrent chemotherapy | ||

| Yes | 16 (38.1%) | 10 (37.0%) |

| No | 26 (61.9%) | 17 (63.0%) |

Abbreviations: ECOG PS = Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status; SNUC = sinonasal undifferentiated carcinoma.

At the time of initial diagnosis, all patients underwent a complete history and physical exam including a flexible nasopharyngolaryngoscopy. All patients received computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Positron emission tomography scans were performed at the discretion of the treating physician. A biopsy was obtained in all patients. Tumor staging was based on the seventh edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer staging system.

All patients were treated supine with a custom thermoplastic immobilization device. High-resolution CT imaging was obtained for treatment planning purposes. Treatment target volumes were identified per the respective institutional guidelines.

PBT was delivered using either a uniform scanning (49 patients, 71%) or a pencil-beam scanning delivery system (20 patients, 29%). In addition, 14 patients (20%) received PBT as a boost combined with photon or neutron therapy. Anterior fields were most typically used. Median PBT dose was 58.5 Gy (RBE; range, 12-78.3; de novo) and 60.0 Gy (RBE; range, 18.2-72.3; re-RT), and median dose per fraction was 2.0 Gy (RBE) for both cohorts disease outcomes for de novo irradiation and reirradiation (re-RT) patients were analyzed separately. The majority of patients were treated with radiation therapy alone. The impact of surgery was not analyzed.

Acute and late toxicities were graded and recorded according to the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events CTCAE version 4.0.

Statistical analysis

Kaplan-Meier survival curves were calculated for overall survival (OS), freedom from distant metastasis (FFDM), freedom from disease progression (FFDP), and freedom from locoregional recurrence (FFLR). Survival curves were calculated separately for patients receiving de novo irradiation and re-RT. All statistical hypothesis tests were 2-sided; P values < .05 were considered to be statistically significant. Differences in survival curves were compared using the log-rank test. All analyses were performed in SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). OS was defined from the day of initiation of PBT to the date of death or censored at last follow-up. FFDP was defined as from the day of initiation of PBT to the first day of confirmation of recurrent disease whether local, regional, or metastatic. FFLR was defined as any recurrence within the radiation fields or regional lymph nodes. All other recurrences were cataloged as distant failure.

Results

The median follow-up for surviving patients was 26.4 months (range, 3.5-220.5 months). Patient and treatment characteristics for de novo patients and re-RT patients are summarized in Table 1. In the de novo cohort, 13 patients (31%) had surgical resection before PBT. All but 3 of these patients had a gross total resection. In the re-RT cohort, 13 patients (48%) had surgical resection before PBT. All but 2 of these patients had a gross total resection.

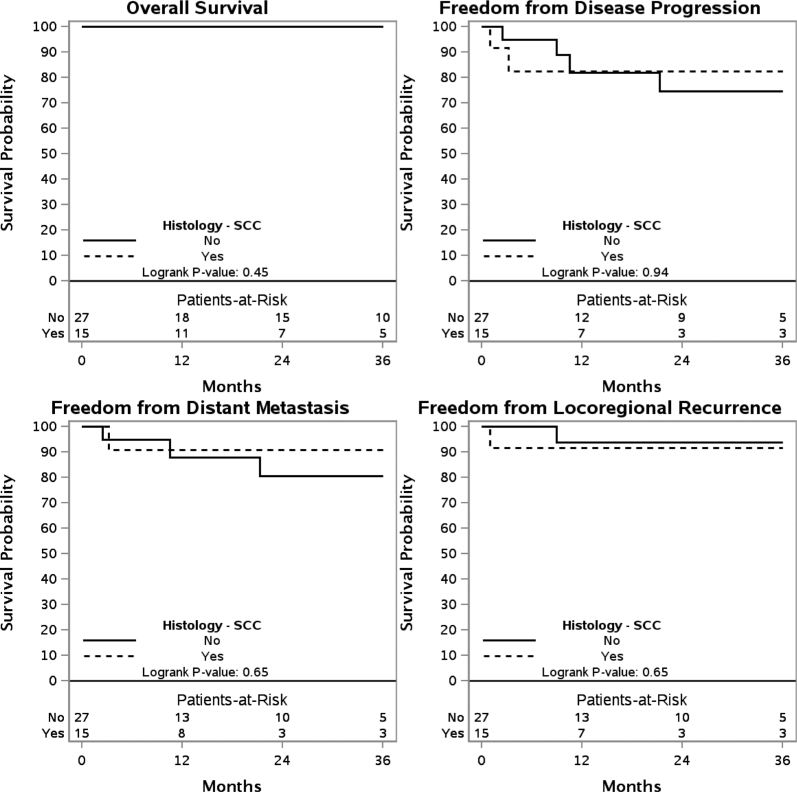

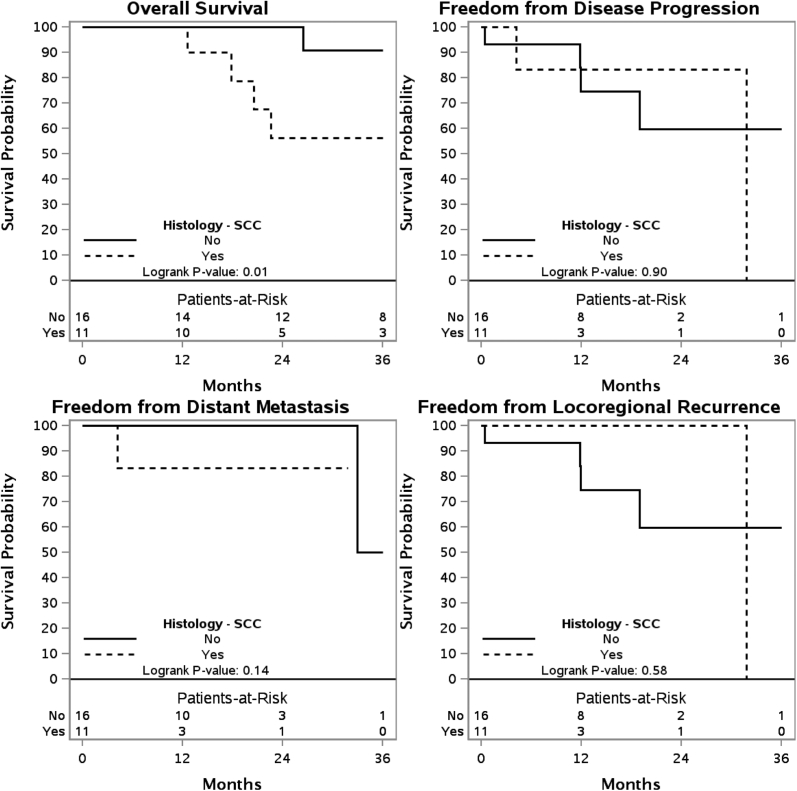

The 3 year OS, FFDM, FFDP, and FFLR are shown for patients who have received de novo irradiation (Fig 1) and those who have received re-RT (Fig 2). These outcomes are also shown for de novo irradiation (Fig 3) and re-RT (Fig 4) based on SCC histology.

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier estimates of overall survival, freedom from distant metastasis, freedom from disease progression, and freedom from locoregional recurrence in patients receiving de novo irradiation.

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier estimates of overall survival, freedom from distant metastasis, freedom from disease progression, and freedom from locoregional recurrence in patients receiving reirradiation.

Figure 3.

Kaplan-Meier estimates of overall survival, freedom from distant metastasis, freedom from disease progression, and freedom from locoregional recurrence in patients receiving de novo irradiation with squamous cell carcinoma histology.

Figure 4.

Kaplan-Meier estimates of overall survival, freedom from distant metastasis, freedom from disease progression, and freedom from locoregional recurrence in patients receiving reirradiation with squamous cell carcinoma histology.

On univariate analysis of patients who received de novo irradiation, lymph node involvement was associated with inferior FFLR (P < .01). In patients who received re-RT, SCC histology was associated with inferior OS (P < .01). When directly comparing the de novo irradiation to re-RT cohorts, re-RT was associated with inferior FFLR (P = .04).

A total of 12 patients (17.4%) had recurrent disease after PBT (Table 2). The patient with a regional failure was a Kadish Stage B esthesioneuroblastoma that was initially treated with photon radiation therapy, received PBT for a local recurrence (48.11 GyE in 24 fractions), and subsequently recurred in the neck and distantly. However, the patient is currently alive on last follow-up. Overall, PBT was well tolerated. Three patients (4.3%) required a percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy tube placed during PBT. There were 11 patients with acute grade 3 toxicities. Acute grade 3 toxicities are summarizing in Table 3. Late toxicities occurred in 15% of the patients and were limited to grade 1-2 toxicities. There were no grade ≥3 late toxicities. No patients developed vision loss or symptomatic brain necrosis.

Table 2.

Patients with recurrence

| Patient | Age | Primary site | Histology | Stage | PBT dose (Gy) | Re-RT | Concurrent chemotherapy | Type of recurrence | Method of diagnosing recurrence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 47 | Ethmoid sinus | Small cell neuroendocrine | IVB | 70 | No | Cisplatin | Local: Skull base | Pathologic |

| 2 | 36 | Nasal cavity | Small cell neuroendocrine | IVB | 63 | Yes | Cisplatin | Local: Bilateral ethmoid sinus | Pathologic |

| 3 | 62 | Ethmoid sinus | Adenocarcinoma | IVA | 50 | Yes | Cisplatin | Local: Nasal mucosa and left maxillary sinus | Pathologic |

| 4 | 60 | Nasal cavity | Squamous cell carcinoma | IVA | 68 | Yes | None | Local: Nasal cavity | MRI |

| 5 | 72 | Nasal cavity | Squamous cell carcinoma | IVA | 34 | Yes | Cetuximab | Local: Nasal cavity | Unknown |

| 6 | 34 | Maxillary sinus | Adenoid cystic carcinoma | IVA | 30 | Yes | None | Local: Left orbit | Physical exam |

| 7 | 77 | Paranasal sinus | Esthesioneuroblastoma | II | 48 | Yes | None | Regional and distant | PET |

| 8 | 32 | Maxillary sinus | Squamous cell carcinoma | IVB | 60 | No | Cetuximab | Distant | MRI |

| 9 | 54 | Maxillary sinus | Adenoid cystic carcinoma | III | 60 | No | Carboplatin | Distant | PET |

| 10 | 56 | Ethmoid sinus | Adenocarcinoma | IVA | 70 | No | Cisplatin | Distant | MRI |

| 11 | 45 | Paranasal sinus | Squamous cell carcinoma | IVB | 65 | Yes | None | Distant | MRI |

| 12 | 20 | Nasal Cavity | Squamous cell carcinoma | IVC | 66 | No | None | Distant | PET |

Abbreviations: MRI = magnetic resonance imaging; PET = Positron emission tomography.

Table 3.

Grade 3 acute toxicity

| Grade 3 acute toxicity | No. of patients (% of n = 69) |

|---|---|

| Mucositis | 8 (11.6%) |

| Pain | 4 (5.8%) |

| Dermatitis | 3 (4.3%) |

| Dry mouth | 2 (2.9%) |

| Dysphagia | 2 (2.9%) |

| Anorexia | 2 (2.9%) |

| Conjunctivitis | 1 (1.4%) |

| Hearing impairment | 1 (1.4%) |

| Nausea | 1 (1.4%) |

Discussion

Sinonasal tumors are an uncommon and heterogeneous type of head and neck cancer.1 There are no randomized trials that have evaluated treatment options for sinonasal tumors, thus treatment recommendations have been guided by retrospective, small studies. To our knowledge, this multi-institutional experience is one of the largest reported studies of patients with sinonasal tumors treated with PBT as a component of their radiation therapy. This study demonstrates that PBT seems to be safe in patients with sinonasal tumors.

In our study, the rate of OS, FFLR, FFDP, and FFLR are comparable with the meta-analysis of charged particle therapy versus photon therapy by Patel and colleagues.16 In addition, primary radiation therapy controlled the overwhelming majority of advanced sinonasal cancer in this cohort. Published series of sinonasal tumors treated with PBT are summarized in Table 4. Russo et al evaluated the Massachusetts General Hospital experience of sinonasal tumors treated with PBT and reported 2-year overall survival and local control rates of 67% and 80%, respectively.18 Dagan et al evaluated the University of Florida experience of sinonasal tumors treated with PBT and reported 3-year overall survival and local control rates of 68% and 83%, respectively.13 Although all patients who received de novo irradiation were alive at 3 years in our study, we acknowledge the limitation of the small number of patients in this cohort. Long-term follow-up is needed to confirm these findings. However, these early results demonstrate that PBT may be an effective treatment option for patients with sinonasal tumors.

Table 4.

Published series of proton beam therapy for sinonasal tumors

| Author | Study period | Institution (country) | Histology | No. of patients | Median age | RT modality | Median RT dose | Median follow-up (mo) | LC (y) | OS (y) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fitzek et al21 | 1992-1998 | Massachusetts General Hospital (US) | ENB, NEC | 19 | 44 | Proton + photon | 69.2 Gy | 45 | 88% (5) | 74% (5) |

| 2002 | ||||||||||

| Weber et al22 | 1991-2001 | Massachusetts General Hospital (US) | SCC, ACC, ENB, PNET, sarcoma, TCC, SNUC, teratocarcinoma | 36 | 54 | Proton + photon | 69.6 Gy | 52.4 | 77.4% (3)† | 90.4% (3) |

| 2006 | 73.1 (5)† | 80.8% (5) | ||||||||

| Truong et al23 | 1991-2005 | Massachusetts General Hospital (United States) | SCC, ACC, NEC Adeno | 20 | 53 | Proton | 76 Gy | 27 | 86% (2) | 53% (2) |

| 2009 | 31% (2)† | |||||||||

| Zenda et al24 | 1999-2006 | National Cancer Center Hospital East (Japan) | SCC, mucosal melanoma, ACC, ENB, SNUC | 39 | 57 | Proton | 65 Gy | 45.4 | 77% (1) | 59% (3) |

| 2011 | ||||||||||

| Fukumitsu et al25 | 2001-2007 | University of Tsukuba (Japan) | SCC, Adeno, ACC, SNUC, MCC | 17 | 62 | Proton | 78 GyE | 23 | 35% (2) | 47.1% (2) |

| 2012 | 17.5% (5) | 15.7% (5) | ||||||||

| Okano et al26 | 2006-2012 | National Cancer Center Hospital East (Japan) | SCC, Adeno, SNUC, ENB, small cell carcinoma | 13 | 47 | Proton | 65 GyE | 56.5 | 33.8 (5)† | 75.5% (5) |

| 2012 | ||||||||||

| Herr et al27 | 1997-2013 | Massachusetts General Hospital (US) | ENB | 22 | 46 | Proton | 66.5 GyE | 73 | 86.4% (5)† | 95.2% (5) |

| 2014 | ||||||||||

| Demizu et al28 | 2003-2011 | Hyogo Ion Beam Medical Center (Japan) | Mucosal melanoma | 62 | 71 | Proton, Carbon Ion | 65 GyE | 18 | 93% (1) | 93% (1) |

| 2009 | 78% (2) | 61% (2) | ||||||||

| Fuji et al29 | 2006-2010 | Shizuoka Cancer Center Hospital (Japan) | Mucosal melanoma | 20 | 74 | Proton | 70 GyE | 35 | 62% (5) | 51% (5) |

| 2014 | 38% (5)† | |||||||||

| Patel et al16 Review | 1990-2014 | N/A | SCC, ACC, Adeno, ENB, other | 212 | 59 | IMRT | 61.4 Gy | 40 | 34 (5)∗ | 45 (5) |

| 2014 | 124 | 58 | Proton | 60.1 GyE | 38 | 55 (5)∗ | 70 (5) | |||

| Russo et al18 | 1991-2008 | Massachusetts General Hospital (US) | SCC | 54 | 56 | Proton | 72.8 GyE | 82 | 80% (2) | 67% (2) |

| 2016 | 80% (5) | 47% (5) | ||||||||

| Dagan et al13 | 2007-2013 | University of Florida (US) | ENB, SCC, ACC, Adeno, SNUC, NEC, mucoepidermoid carcinoma | 84 | 59 | Proton + photon | 73.8 GyE | 28.8 | 83% (3) | 68% (3) |

| 2016 | 73% (3)† | |||||||||

| Toyomasu et al30 | 2001-2012 | Hyogo Ion Beam Medical Center (Japan) | SCC | 59 | 60 | Proton, Carbon Ion | 67.6 GyE | 30 | 54% (3) | 56.2% (3) |

| 2018 | 50.4% (5) | 41.6% (5) | ||||||||

| Present study | 2010-2016 | Proton Collaborative Group | SCC, ACC, ENB, Adeno, small cell, SNUC | 69 | 55.9 | Proton, photon, neutron | 53.8 GyE | 26.4 | 92.9% (3) | 100% (3) |

| 58.1 (Re-RT) | 54.5 GyE (Re-RT) | 33.8% (3 Re-RT) | 76% (3 Re-RT) |

Abbreviations: ACC = adenoid cystic carcinoma; Adeno = adenocarcinoma; ENB = esthesioneuroblastoma; MCC = myoepithelial cell carcinoma; NEC = neuroendocrine carcinoma; PNET = primitive neuroectodermal tumor; RT = radiation therapy; SCC = squamous cell carcinoma; SNUC = sinonasal undifferentiated carcinoma; TCC = transitional cell carcinoma.

Locoregional control.

Disease-free survival.

The predominant pattern of failure has been demonstrated to be local recurrence. The University of Florida experience reported that local recurrence accounted for 60.7% of the failures.13 Russo et al also reported a predominantly local recurrence pattern in sinonasal SCC.18 Our study demonstrates that locoregional recurrence is a significant component of disease progression. Historically, local control in sinonasal malignancies has been demonstrated to be one of the most significant factors for overall disease control. Our study indicates that recurrent disease requiring re-RT is independently a poor prognostic factor in terms of locoregional control. In addition, re-RT patients with SCC had an inferior overall survival when compared with other histologies, an expected finding considering SCC is considered a higher risk histology in sinonasal tumors. Although not statistically significant, patients with SCC in the University of Florida experience also had the worst 3-year overall survival rate when compared with other histologies.13

PBT was well tolerated in our study and seems to have favorable toxicities compared with prior photon reports. No patients in our study experienced vision loss or symptomatic brain necrosis. Although there were no documented grade ≥3 late toxicities, the toxicity data was potentially underreported in our cohort. These results should be interpreted with caution especially in the re-RT setting. Demizu et al reported a 9.6% rate of optic neuropathy with charged particle therapy.28 Particularly for sinonasal tumors, PBT allows for increased target coverage and dose escalation with simultaneous maximal sparing of healthy tissue. PBT has further theoretical advantages over IMRT, including an ability to deposit an increased biologic effective dose to a target with almost no exit dose. Conventional photon radiation therapy is limited by the dose that can be safely administered without harming adjacent optic structures. Jiang et al reported vision loss from radiation-induced optic neuropathy in 8.1% of patients treated with photon radiation therapy.31 Advances in IMRT have improved clinical outcomes in terms of long-term ocular toxicity.32 Although it seems that the rate of optic neuropathy with PBT is comparable to photon therapy, reported series of patients who are treated with PBT likely represent an inherently complex cohort of sinonasal tumors. Nevertheless, PBT has been reported to have at least comparable long-term toxicities when directly compared with conventional photon therapy.

This study has several limitations. This is a retrospective series of a group of a heterogeneous group of malignancies with a relatively short follow-up period. Although all patients received curative intent PBT, there was heterogeneity within the treatment regimen. PBT was delivered with varying techniques, and patients who were treated with combined proton and photon therapy were included in the analysis. Thus, this is not purely a charged particle study. In addition, the impact of surgery was not analyzed in this study. Toxicities reported in our study may be incomplete due to institutional variability in follow-up protocol and reporting. This limits our ability to draw definitive conclusions. However, this is one of the largest series of patients with sinonasal tumors treated with PBT with limited late toxicities. It is important to recognize that patients with a historically poor prognosis such as SCC and re-RT were included and analyzed in this study.

The PCG multi-institutional registry experience is consistent with prior published series of patients with sinonasal tumors treated with PBT (Table 4). Our analysis suggests that PBT is safe and efficacious for treatment of sinonasal tumors.

Conclusions

Sinonasal tumors are rare and can be challenging to treat. Charged particle therapy in the form of proton beam therapy is a promising treatment option. Our findings suggest that proton beam therapy may be a safe and efficacious treatment option for patients with sinonasal tumors. This analysis is in concordance with recent published series of patients with sinonasal tumors treated with proton beam therapy.

Footnotes

Preliminary data were presented at Particle Therapy Co-Operative Group (PTCOG) 56 in Japan.

Sources of support: No funding was received for this study.

Disclosures: Gary L. Larson is an equity holder in the Procure Proton Therapy Center in Oklahoma City. All other authors have no financial or nonfinancial competing interests to be declared.

References

- 1.Turner J.H., Reh D.D. Incidence and survival in patients with sinonasal cancer: A historical analysis of population-based data. Head Neck. 2012;34:877–885. doi: 10.1002/hed.21830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Haerle S.K., Gullane P.J., Witterick I.J., Zweifel C., Gentili F. Sinonasal carcinomas: Epidemiology, pathology, and management. Neurosurg Clin N Am. 2013;24:39–49. doi: 10.1016/j.nec.2012.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lewis J.S., Jr. Sinonasal squamous cell carcinoma: A review with emphasis on emerging histologic subtypes and the role of human papillomavirus. Head Neck Pathol. 2016;10:60–67. doi: 10.1007/s12105-016-0692-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blanch J.L., Ruiz A.M., Alos L., Traserra-Coderch J., Bernal-Sprekelsen M. Treatment of 125 sinonasal tumors: Prognostic factors, outcome, and follow-up. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2004;131:973–976. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2004.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen A.M., Daly M.E., Bucci M.K. Carcinomas of the paranasal sinuses and nasal cavity treated with radiotherapy at a single institution over five decades: Are we making improvement? Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2007;69:141–147. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2007.02.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Daly M.E., Chen A.M., Bucci M.K. Intensity-modulated radiation therapy for malignancies of the nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2007;67:151–157. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2006.07.1389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guan X., Wang X., Liu Y., Hu C., Zhu G. Lymph node metastasis in sinonasal squamous cell carcinoma treated with IMRT/3D-CRT. Oral Oncol. 2013;49:60–65. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2012.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hoppe B.S., Stegman L.D., Zelefsky M.J. Treatment of nasal cavity and paranasal sinus cancer with modern radiotherapy techniques in the postoperative setting—the MSKCC experience. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2007;67:691–702. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2006.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mendenhall W.M., Amdur R.J., Morris C.G. Carcinoma of the nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses. Laryngoscope. 2009;119:899–906. doi: 10.1002/lary.20196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Paulino A.C., Marks J.E., Bricker P., Melian E., Reddy S.P., Emami B. Results of treatment of patients with maxillary sinus carcinoma. Cancer. 1998;83:457–465. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chopra S., Kamdar D.P., Cohen D.S. Outcomes of nonsurgical management of locally advanced carcinomas of the sinonasal cavity. Laryngoscope. 2017;127:855–861. doi: 10.1002/lary.26228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harrison L.B., Kies M.S., Sessions R.B. 4th ed. Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; Philadelphia: 2014. Head and Neck Cancer a Multidisciplinary Approach. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dagan R., Bryant C., Li Z. Outcomes of sinonasal cancer treated with proton therapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2016;95:377–385. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2016.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chan A.W., Liebsch N.J. Proton radiation therapy for head and neck cancer. J Surg Oncol. 2008;97:697–700. doi: 10.1002/jso.21013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Frank S.J., Selek U. Proton beam radiation therapy for head and neck malignancies. Curr Oncol Rep. 2010;12:202–207. doi: 10.1007/s11912-010-0089-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Patel S.H., Wang Z., Wong W.W. Charged particle therapy versus photon therapy for paranasal sinus and nasal cavity malignant diseases: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15:1027–1038. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(14)70268-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ramaekers B.L., Pijls-Johannesma M., Joore M.A. Systematic review and meta-analysis of radiotherapy in various head and neck cancers: Comparing photons, carbon-ions and protons. Cancer Treat Rev. 2011;37:185–201. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2010.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Russo A.L., Adams J.A., Weyman E.A. Long-term outcomes after proton beam therapy for sinonasal squamous cell carcinoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2016;95:368–376. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2016.02.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.van de Water T.A., Bijl H.P., Schilstra C., Pijls-Johannesma M., Langendijk J.A. The potential benefit of radiotherapy with protons in head and neck cancer with respect to normal tissue sparing: A systematic review of literature. Oncologist. 2011;16:366–377. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2010-0171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McDonald M.W., Liu Y., Moore M.G., Johnstone P.A. Acute toxicity in comprehensive head and neck radiation for nasopharynx and paranasal sinus cancers: Cohort comparison of 3D conformal proton therapy and intensity modulated radiation therapy. Radiat Oncol. 2016;11:32. doi: 10.1186/s13014-016-0600-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fitzek M.M., Thornton A.F., Varvares M. Neuroendocrine tumors of the sinonasal tract. Results of a prospective study incorporating chemotherapy, surgery, and combined proton-photon radiotherapy. Cancer. 2002;94:2623–2634. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Weber D.C., Chan A.W., Lessell S. Visual outcome of accelerated fractionated radiation for advanced sinonasal malignancies employing photons/protons. Radiother Oncol. 2006;81:243–249. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2006.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Truong M.T., Kamat U.R., Liebsch N.J. Proton radiation therapy for primary sphenoid sinus malignancies: Treatment outcome and prognostic factors. Head Neck. 2009;31:1297–1308. doi: 10.1002/hed.21092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zenda S., Kohno R., Kawashima M. Proton beam therapy for unresectable malignancies of the nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2011;81:1473–1478. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2010.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fukumitsu N., Okumura T., Mizumoto M. Outcome of T4 (International Union Against Cancer Staging System, 7th edition) or recurrent nasal cavity and paranasal sinus carcinoma treated with proton beam. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2012;83:704–711. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2011.07.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Okano S., Tahara M., Zenda S. Induction chemotherapy with docetaxel, cisplatin and S-1 followed by proton beam therapy concurrent with cisplatin in patients with T4b nasal and sinonasal malignancies. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2012;42:691–696. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hys096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Herr M.W., Sethi R.K., Meier J.C. Esthesioneuroblastoma: An update on the Massachusetts eye and ear infirmary and Massachusetts general hospital experience with craniofacial resection, proton beam radiation, and chemotherapy. J Neurol Surg B Skull Base. 2014;75:58–64. doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1356493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Demizu Y., Murakami M., Miyawaki D. Analysis of vision loss caused by radiation-induced optic neuropathy after particle therapy for head-and-neck and skull-base tumors adjacent to optic nerves. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2009;75:1487–1492. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2008.12.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fuji H., Yoshikawa S., Kasami M. High-dose proton beam therapy for sinonasal mucosal malignant melanoma. Radiat Oncol. 2014;9:162. doi: 10.1186/1748-717X-9-162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Toyomasu Y., Demizu Y., Matsuo Y. Outcomes of patients with sinonasal squamous cell carcinoma treated with particle therapy using protons or carbon ions. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2018;101:1096–1103. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2018.04.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jiang G.L., Tucker S.L., Guttenberger R. Radiation-induced injury to the visual pathway. Radiother Oncol. 1994;30:17–25. doi: 10.1016/0167-8140(94)90005-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Duprez F., Madani I., Morbee L. IMRT for sinonasal tumors minimizes severe late ocular toxicity and preserves disease control and survival. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2012;83:252–259. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2011.06.1977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]