Summary

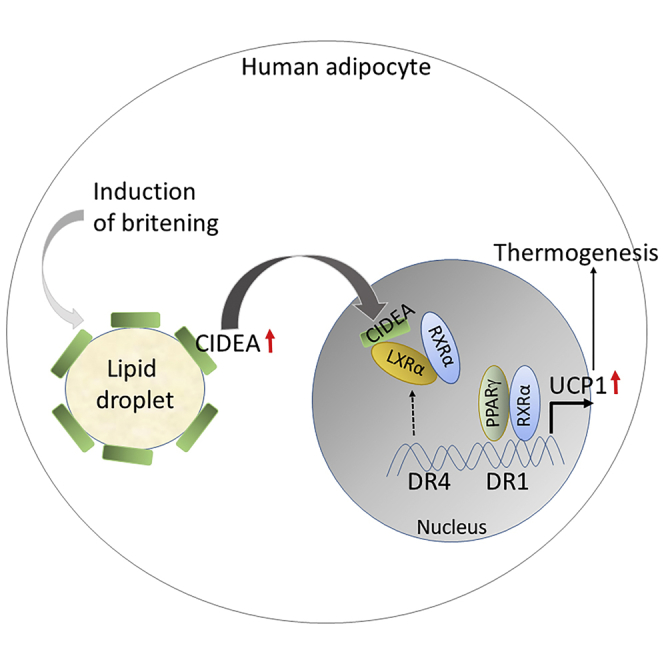

Our study identifies a transcriptional role of cell death-inducing DNA fragmentation factor-like effector A (CIDEA), a lipid-droplet-associated protein, whereby it regulates human adipocyte britening/beiging with consequences for the regulation of energy expenditure. The comprehensive transcriptome analysis revealed CIDEA's control over thermogenic function in brite/beige human adipocytes. In the absence of CIDEA, achieved by the modified dual-RNA-based CRISPR-Cas9nD10A system, adipocytes lost their britening capability, which was recovered upon CIDEA re-expression. Uncoupling protein 1 (UCP1), the most upregulated gene in brite human adipocytes, was suppressed in CIDEA knockout (KO) primary human adipocytes. Mechanistically, during induced britening, CIDEA shuttled from lipid droplets to the nucleus via an unusual nuclear bipartite signal in a concentration-dependent manner. In the nucleus, it specifically inhibited LXRα repression of UCP1 enhancer activity and strengthened PPARγ binding to UCP1 enhancer, hence driving UCP1 transcription. Overall, our study defines the role of CIDEA in increasing thermogenesis in human adipocytes.

Subject Areas: Biological Sciences, Molecular Biology, Cell Biology, Transcriptomics

Graphical Abstract

Highlights

-

•

CIDEA knockout inhibits britening and uncoupling in human adipocytes

-

•

The induction of britening induces CIDEA expression and nuclear translocation

-

•

CIDEA inhibits LXRα repression of UCP1 enhancer activity

-

•

CIDEA enhances PPARγ binding to a UCP1 enhancer element to drive UCP1 transcription

Biological Sciences; Molecular Biology; Cell Biology; Transcriptomics

Introduction

The identification and characterization of brite/beige (a.k.a. brown-like) adipocytes has drawn considerable attention, as these cells are thought to regulate energy production and may help combat obesity and insulin resistance (Nedergaard and Cannon, 2010, Vernochet et al., 2010). Adult humans possess brown adipocytes that are activated by cold stimuli via the sympathetic nervous system (Nedergaard et al., 2007, Nedergaard and Cannon, 2010, Nedergaard and Cannon, 2013). Progenitors isolated from subcutaneous white fat from children or adults can be induced to acquire a brite phenotype (Ahmadian et al., 2011, Fisher et al., 2012, Ohno et al., 2012), characterized by enhanced oxygen consumption and expression of uncoupling protein 1 (UCP1) and cell-death inducing DNA fragmentation factor-like effector A (CIDEA).

CIDEA downregulates UCP1 activity in brown adipose tissue (Zhou et al., 2003). Originally thought to be a mitochondrial protein, CIDEA was later discovered to be a lipid droplet (LD)-associated protein (Christianson et al., 2010, Puri et al., 2008, Reynolds et al., 2015) not localized to mitochondria in adipocytes. Unlike in mice (Zhou et al., 2003), CIDEA expression in human adipocytes correlates with insulin sensitivity (Puri et al., 2008) and lipid disorders in obese patients (Feldo et al., 2013). Furthermore, a CIDEA polymorphism has been associated with a clinical metabolic phenotype (Dahlman et al., 2005, Nordstrom et al., 2005, Wu et al., 2013, Zhang et al., 2008). CIDEA is endogenously expressed in human but not in rodent white adipocytes. A study by Kulyte et al. provided a strong rationale to our study where they have shown that CIDEA localizes in both the cytoplasm and the nucleus and it binds to liver X receptors (LXR) to regulate their activity in human white adipocytes (Kulyte et al., 2011). Also, CIDEA was found to be expressed at abnormally high levels in white adipose tissue from cachexic patients and CIDEA overexpression in vitro inhibited glucose oxidation while stimulating fatty acid oxidation (FAO) (Laurencikiene et al., 2008). Transgenic mice expressing human-CIDEA specifically in adipose tissue show an improved metabolic profile through expansion of adipose tissue (Abreu-Vieira et al., 2015), suggesting that human CIDEA might be functionally different than the mouse CIDEA. Considered a brown adipocyte marker in mice, CIDEA expression increases with britening of mouse white adipocytes (Barneda et al., 2013, Harms and Seale, 2013, Hiraike et al., 2017, McDonald et al., 2015, Qiang et al., 2012, Seale et al., 2007, Seale et al., 2008, Vernochet et al., 2009, Wang et al., 2016). Beyond its associations with thermoregulation (Barneda et al., 2013, Harms and Seale, 2013, McDonald et al., 2015, Qiang et al., 2012, Seale et al., 2007, Vernochet et al., 2009), lipid droplet dynamics, and lipid metabolism (Barneda et al., 2015, Puri et al., 2008, Wu et al., 2014), little is known about the molecular role of CIDEA in britening and thermogenesis of human adipocytes.

To delineate the association of CIDEA with thermogenesis in humans, we established a positive correlation of CIDEA and UCP1 expression in britened human adipose tissue. We then used human primary white adipose tissue-derived stromal vascular cells (hADSCs) as a model system and developed dual RNA-based CRISPR-Cas9 system to knock out CIDEA in primary human cells. We also developed a modified RNA methodology for dose-dependent expression of CIDEA in human adipocytes. Brite adipocytes exhibited elevated UCP1 expression and increased mitochondrial biogenesis along with brite/beige markers. Our studies reveal that during britening CIDEA expression increases and it translocates to the nucleus via a nuclear bipartite signal. In the nucleus, CIDEA induces a brite phenotype in human adipocytes by transcriptional regulation of UCP1 via directly interacting with Liver X Receptor alpha, LXRα, and weakening its binding to UCP1 enhancer. Our studies also identified that CIDEA strengthened PPARγ binding to UCP1 enhancer. Overall, our study identifies a molecular mechanism of CIDEA-mediated regulation of britening and maintenance of brite phenotype in primary human adipocytes.

Results

CIDEA Expression in Human Brite Adipose Tissue Correlates with UCP1 Expression

Treatment of subcutaneous white adipose tissue explants from five obese human subjects with 1 μM rosiglitazone (Rosi) for 7 days induced CIDEA and UCP1 expression reliably (Figure S1A). An average 2.5-fold increase in CIDEA expression correlated with an ~55-fold increase in UCP1 expression, which was negligible without treatment. This britening process was independent of demographics and body mass index. These preliminary studies complimented the role of CIDEA in healthy metabolic phenotype in humans (Dahlman et al., 2005, Feldo et al., 2013, Gummesson et al., 2007, Nordstrom et al., 2005, Puri et al., 2008, Wu et al., 2013, Zhang et al., 2008).

Modified CRISPR-Cas9nD10A Methodology to Knock Out CIDEA in Cultured Human Primary Adipocytes

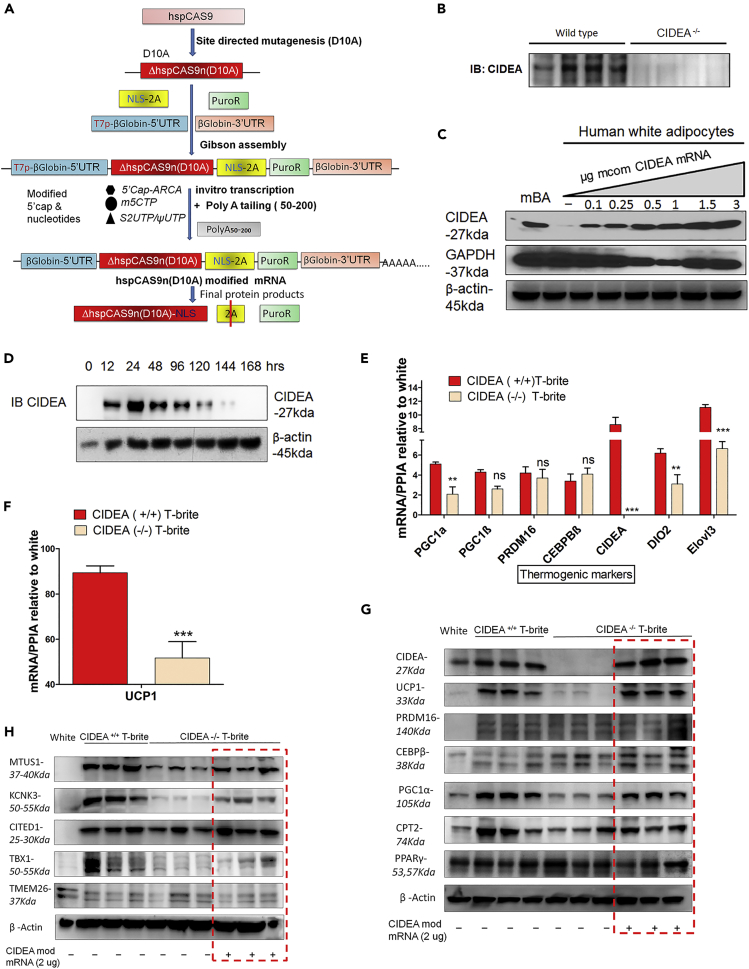

To study the loss of function of CIDEA in human primary cells, we established a modified efficient genome engineering method for genetic manipulation in adipocytes differentiated from hADSC. We modified the existing CRISPR/Cas9 system to knock out CIDEA in multipotent human adipose-derived stromal progenitor cells (hADSCs) from freshly isolated human subcutaneous adipose tissue. To achieve an efficient CIDEA knockout (KO), we designed multiple single guide RNA (sgRNA) in combination of Cas9 or its mutated form to target the CIDEA gene loci (Figure 1A; also see Figures S1, S2, and S3A–S3C and Supplemental Information). With our modified CRISPR-Cas9nD10A nickase methodology, we were able to knock out CIDEA in human adipocytes (Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

CIDEA KO Inhibits Britening of Human White Adipocytes

(A) CRISPR-Cas9 construction. Hybrid Cas9 construct (Cas9D10A-2A-P) and modified human Cas9 mRNA synthesis workflow.

(B) Western blot showing CRISPR-Cas9D10A nickase-mediated abolishment of CIDEA in four biallelic clones of mature adipocytes.

(C) CIDEA protein expression profile after dose-dependent mcom CIDEA mRNA single transfection (24 h) into human white adipocytes. Mouse brown adipocyte (mBA) lysate was blotted as a positive control.

(D) Time course expression profile of mcom CIDEA mRNA after single transfection into Hek293T cells. Modified codon-optimized CIDEA mRNA (mcom CIDEA-mRNA; also called CIDEA mod mRNA) produced eloquent dose- and time-dependent control of CIDEA expression (C and D).

(E and F) Expression of thermogenic genes (E) and UCP1 (F) in Rosi-treated WT (CIDEA+/+) and KO (CIDEA−/−) T-brites derived from hADSCs. CIDEA−/− cells were derived from WT hADSCs by CRISPR-CAS9-mediated KO. Data are expressed as fold changes over dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO; vehicle)-treated adipocytes, and each data point represents pooled cell fractions from three individual donors. Data are mean ± SEM (n = 3). ***p < 0.001, and **p < .01, two-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni post tests.

(G and H) Protein expression of thermogenic (G) and brite genes (H) in CIDEA+/+ and CIDEA−/− T-brites treated with Rosi. After 7 days of Rosi, CIDEA−/− adipocytes were transfected with GFP control mRNA or mcom-CIDEA mRNA (red box) to re-express CIDEA for 3 days. Each lane in the red box represents an individual CIDEA−/− clone.

We next developed a modified-mRNA methodology to perform gain-of-function studies (Figure S3D). Modified codon-optimized CIDEA mRNA (mcom CIDEA-mRNA; also called CIDEA mod mRNA) produced eloquent dose- and time-dependent control of CIDEA expression within physiological limits (Figures 1C and 1D; also see Methods and Figures S3E–S3G). In all our further studies, 1–2 μg mcom CIDEA-mRNA was used.

Thiazolidinedione-Induced Human Adipocyte Britening

Human brite adipocytes, termed T-brites, were obtained by treating mature white adipocytes, that had been differentiated from hADSCs (Lee et al., 2012, Lee et al., 2013), with 1 μg/mL Rosi for 7 days. Relative to untreated control cells, T-brites had increased mRNA expression of PPARγ target genes (ADIPOQ, FABP3, FABP4, and RXRA) and brite/beige marker genes (PGC1α/β, PRDM16, CEBPβ, CIDEA, and ELOVL3), without expression changes in lipogenic genes (FASN and SCD1) (Figures S4A and S4B). Notably, T-brites exhibited an 85-fold increase in UCP1 mRNA expression (Figure S4C) together with increased mRNA expression of other brite marker genes (CITED, TBX1, MTUS1, and KCNK3) (Figure S4D). We did not detect changes in the transcription of brown or white marker genes (Figures S4E and S4F, respectively). Induction of PGC1α and PGC1β transcription in T-brites was accompanied by increased transcription of mitochondrial complex I–V components (Figure S4G).

T-brites showed upregulated PLIN1 and ATGL transcription but downregulated transcription of ATGL's inhibitor G0S2 (Figure S4H). Meanwhile, mRNA levels of FSP27, which negatively regulates lipolysis (Grahn et al., 2014, Singh et al., 2014), were unchanged in T-brites, perhaps due to positive regulation by Rosi (Puri et al., 2007, Puri et al., 2008). T-brites exhibited upregulated mRNA expression of acyl coenzyme A dehydrogenase genes (VLCAD, LCAD, MCAD) and other FAO-associated genes (PPARα, CPT1, CPT2) (Figure S4I). The mRNA abundances of TCA cycle enzyme genes (MDH2 and IDH3a) were also increased in T-brites (Figure S4J). T-brites were found to have elevated mitochondrial DNA contents (data not shown), consistent with increased mitochondrial biogenesis and activity, accompanied by increased FAO and TCA cycle entry characteristic of uncoupling events leading to thermogenesis.

Absence of CIDEA Inhibits Britening and Uncoupling in Human Adipocytes

As predicted, CIDEA expression was plentiful in CIDEA+/+ T-brites produced by Rosi induction (Figure 1E). By comparison, CIDEA−/− T-brites produced by CRISPR-Cas9 KO in hADSCs had reduced PGC1α, DIO2, Elovl3, and UCP1 mRNA expression (Figures 1E and 1F), with no significant changes in PGC1β, PRDM16, and CEBPβ mRNA expression (Figure 1E). Other brite genes were reduced in CIDEA−/− T-brites (Figure S5A). BAT markers (Figure S5B) and lipogenic genes (FASN and SCD1; data not shown) were unaffected by CIDEA KO. Expression of the FAO regulatory genes CPT1 and CPT2 was decreased, whereas PPARα, VLCAD, LCAD, and MCAD mRNA levels were unaltered (Figure S5C). Britening-induced increases in mitochondrial DNA copy number were unaffected by CIDEA KO (Figure S5D). Select electron transport chain genes were downregulated in CIDEA−/− T-brites (Figure S5E), whereas adipogenic gene expression did not differ between CIDEA+/+ and CIDEA−/− T-brites (data not shown). CIDEA KO reduced protein expression of PGC1α (PPARγ coactivator 1 alpha), UCP1, CPT (carnitine palmitoyltransferase) 2, CITED (Cbp/P300 interacting transactivator with Glu/Asp-rich carboxy-terminal domain), MTUS (microtubule-associated scaffold protein)1, TBX1 (T-box 1), and KCNK3 (potassium two-pore domain channel subfamily K member 3) but not PPARγ, PRDM16 (PR domain containing 16), CEBPβ (CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein beta), and TMEM (TransMEMbrane protein); these reductions were reversed by CIDEA re-expression (Figures 1G and 1H, red box). These results suggest that CIDEA plays an important role in adipocyte britening via regulation of thermogenic genes.

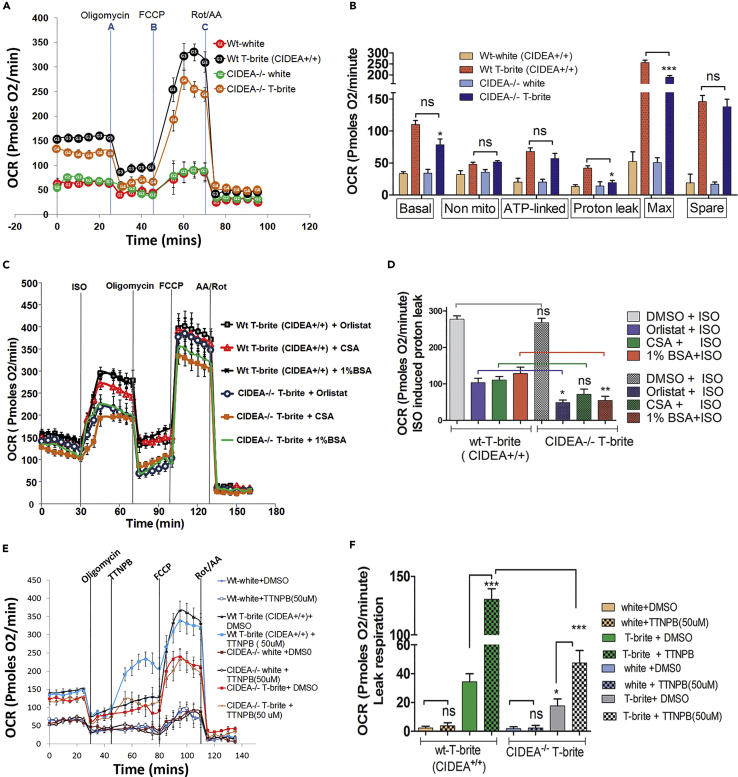

CIDEA KO Diminishes Increased OCR in T-Brites

The basal oxygen consumption rate (OCR) was higher in T-brites than in white adipocytes (Figure 2A). Relative to non-KO controls, CIDEA−/− T-brites had reduced mitochondrial respiration, proton leakage, and maximal respiratory capacity (Figure 2B) but unchanged coupling efficiency and thus unchanged mitochondrial energy production (Figure S6A). These data revealed that irrespective of britening or CIDEA's absence, the efficiency of mitochondrial energy production, above the oligomycin-mediated ATP-block, was same under basal conditions. The cell respiratory ratio (cRCR), a respiratory capacity index, was higher in T-brites than in white adipocytes (Figure S6B). CIDEA KO did not change cRCR, arguably owing to reduced substrate oxidation and proton leakage because cRCR is sensitive to these factors but insensitive to ATP turnover.

Figure 2.

CIDEA KO Inhibits UCP1-dependent OCR in Human Adipocytes Induced for Britening

(A) Seahorse bioanalyzer respirometry of differentiated WT and CIDEA−/− white adipocyte and T-brites show basal respiration, proton leak respiration (after 2 μm oligomycin treatment), maximal substrate oxidation (12 μm FCCP), and non-mitochondrial respiration (5 μm/5 μm antimycin A/rotenone). All data points are an average of 8–10 wells.

(B) Quantification of basal respiration, ATP turnover, proton leak, and maximum respiratory capacity of the samples in panel (A).

(C) Bioenergetics of ISO-induced OCR of WT and CIDEA−/− T-brites pretreated with vehicle (DMSO) or FFA-induced leak respiration blocker (2 h, 20 μm orlistat; 12 h, 6 μg/mL CSA; 1% BSA).

(D) Lipolysis suppression, PTP blockade, or FFA scavenging inhibited ISO-induced leak respiration in CIDEA−/− T-brites.

(E) Time course OCR of WT and CIDEA−/− white and brite/beige adipocytes treated with 50 μM arotinoid acid (TTNPB) or DMSO or after basal and oligomycin-dependent respiration. FCCP and antimycin A/rotenone were added subsequently.

(F) TTNPB increased uncoupled/leak respiration in brite/beige cells in UCP1-dependent manner.

Data in (B), (D), and (F) are mean ± SEM (n = 3). ***p < 0.001 and **p < .01, two-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni post tests.

CIDEA-Mediated Increase in OCR Is UCP1 Dependent

CIDEA inhibition has been shown to increase stimulated lipolysis, thus increasing free fatty acids (FFAs) (Puri et al., 2008). We found that basal lipolysis was increased in CIDEA−/− adipocytes (Figure S2E). Excessive production of intracellular FFAs during lipolysis can mask UCP1-mediated leak respiration through non-specific protonophoric FFA actions and mitochondrial permeability transition pore (PTP) opening (Li et al., 2014). Therefore, we compared T-brite OCRs in wild-type (WT) CIDEA+/+ versus KO CIDEA−/− T-brites stimulated with isoproterenol (ISO), to differentiate CIDEA's involvement in UCP1 activity versus PTP-mediated leak respiration. Injection of T-brites at 30 min time point with the β-adrenoreceptor agonist ISO (to increase endogenous FFAs) increased OCR, with or without CIDEA (Figures 2C and 2D). Maximization of oxidative capacity with the protonophore FCCP [carbonyl cyanide-4-(trifluoromethoxy)phenylhydrazone] during ISO-induced OCR was lower in CIDEA−/− than in CIDEA+/+ T-brites, evidencing a contribution of CIDEA to mitochondrial reserve capacity and uncoupling (Figure 2C). ISO-induced ATP-linked respiration showed no significant difference in CIDEA−/− and CIDEA+/+ T-brites (Figures 2C and 2D), indicating that proton leak was masked in CIDEA−/− cells. Therefore, to assess UCP1's contribution to uncoupled T-brite respiration, we suppressed excess FFA-mediated proton leakage via PTPs with a pretreatment with the lipase inhibitor orlistat, the PTP blocker cyclosporin A (CSA) or the FFA sink BSA (BSA, 1%). The reducing effects of orlistat and 1% BSA on PTP-dependent (UCP1-independent) proton-leak respiration were more pronounced in CIDEA−/− than in CIDEA+/+ T-brites, implicating UCP1 dependence in CIDEA-mediated increases in OCR; the CSA effect did not differ significantly between WT and KO cells (Figures 2C and 2D). Taken together, these results showed that CIDEA KO reduced UCP1-dependent uncoupled respiration.

To further assess the direct contribution of UCP1 to OCR, we administered UCP1 activator, TTNPB (the retinoid analog), after inhibiting coupled oxygen consumption with oligomycin. Because TTNPB increases proton conductance through the inner mitochondrial membrane, we hypothesized that the number of UCP1 molecules present in the inner mitochondrial membrane might correlate with TTNPB-mediated increased respiration. After dose optimization for OCR augmentation without cytotoxicity (data not shown), 50 μM TTNPB was found to have a more robust OCR augmentation effect on oligomycin-inhibited CIDEA+/+ T-brites than on CIDEA−/− T-brites (Figures 2E and 2F); white adipocytes did not respond to TTNPB. CIDEA's role in UCP1-mediated OCR was further confirmed when CIDEA re-expression in CIDEA−/− cells, using CIDEA mcomRNA, restored the TTNPB-induced increase in respiration to nearly the level of control T-brites (Figures S6C and S6D). TTNPB did not alter FCCP efficacy, suggesting different modes of action for the two agents (Figure 6C). Finally, elevated oxidative phosphorylation subunit levels in T-brites, compared with white adipocytes, were decreased by CIDEA KO and recovered with CIDEA re-expression (Figure S6E).

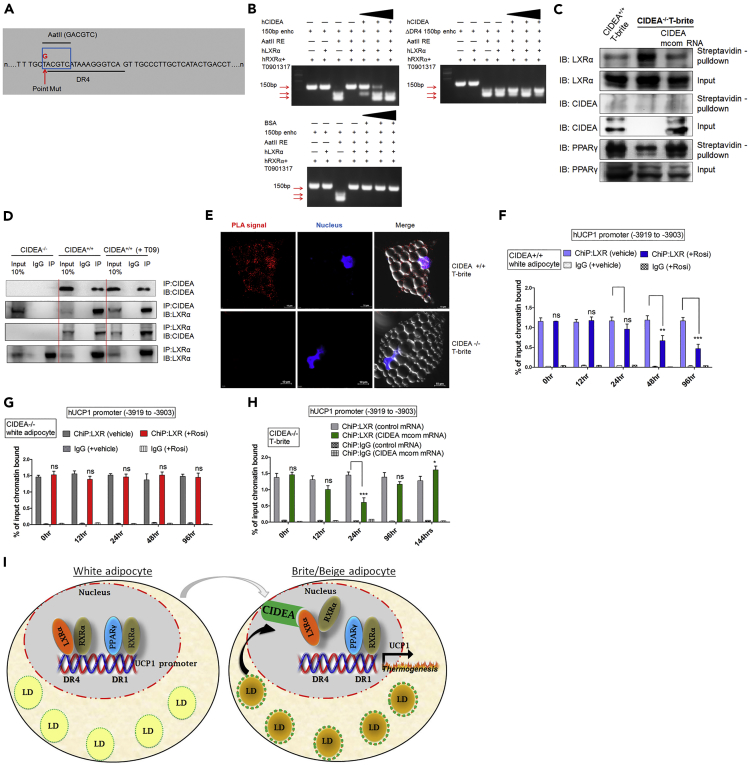

Figure 6.

CIDEA Directly Binds to LXRα to Derepress UCP1 Transcription during Britening

(A) Partial sequence of the WT UCP1 enhancer containing DR4 (LXRα binding site). T-G (red) point mutation (blue box) flanking DR4 that generated an artificial AatII restriction site. It did not alter LXRα binding to DR4 (data not shown).

(B) RFLP-based protein-DNA binding assay showing that LXRα protects synthetic AatII restriction site (lane 4, top left panel). CIDEA increased AatII cleavage efficiency dose dependently (lanes 5–7, top right panel); BSA (negative control) did not stimulate AatII cleavage (lanes 5–7, bottom panel).

(C) LXR and CIDEA immunoblots of streptavidin pull-down assays of nuclear fractions that had been incubated with biotinylated dUER150bp containing DR4.

(D) CIDEA and LXRα coIP and western blots of total cell (20 kDa cutoff) lysate (input) from CIDEA KO, WT, and WT + T09 LXR ligand T-brites.

(E) PLA of CIDEA-LXRα protein-protein interaction in fixed WT T-brites (proteins detected with anti-CIDEA and anti-LXRα antibodies; CIDEA-LXRα interactions within 30–40 nm appear red; blue, Hoechst nuclear counterstain; LDs appear as glossy intracellular globes). Scale bar, 10 μm.

(F and G) ChIP-qPCR analysis of LXRα binding to UCP1 enhancer at −3,919 during Rosi-induced britening of CIDEA+/+ (F) or CIDEA−/− (G) adipocytes.

(H) Time course ChIP-qPCR analysis of hUCP1 enhancer occupancy at −3,919 by LXRα in developing CIDEA−/− T-brites in which mcom-CIDEA mRNA transfection commenced concomitantly with Rosi induction.

(I) Model: Upon induction of human adipocyte britening, increasing concentrations of CIDEA result in CIDEA shuttling to the nucleus, where it interacts directly with LXRα and weakens LXRα binding of the UCP1 enhancer at DR4, thus increasing transcriptional regulation of UCP1 and thermogenesis.

In (F–H), data are mean ± SEM (n = 3). ***p < 0.001, and **p < .01, two-way ANOVAs followed by Bonferroni post-tests.

CIDEA Is Critical for Adipocyte Britening by Various Inducers

To confirm that the role of CIDEA in britening was not specific to Rosi, britening of mature human white adipocytes was induced with a 7-day exposure to 1 nM CL316,243 (a β3 agonist), 100 nM fibroblast growth factor 21 (FGF21), or 100 nM atrial natriuretic peptide (ANP; dosage optimization data not shown) in the presence or absence of CIDEA and confirmed by the characteristics of high mitochondrial content, UCP1 expression, and thermogenic capacity (Bordicchia et al., 2012, Ghorbani and Himms-Hagen, 1997, Granneman et al., 2005). In all cases, levels of transcripts encoding UCP1, PGC1α, CIDEA, PRDM16, and CPT2 transcript levels were robustly increased relative to levels in white adipocytes (Figure S7A). In addition to reducing UCP1 transcription in response to these inducers, KO of CIDEA was associated with lesser induction of several thermogenic and brite marker mRNAs (precise effects varied among inducers, see Figure S7A). Consistent with these mRNA expression data, CIDEA−/− T-brites had lower UCP1, PGC1α, MTUS1, and CITED1 protein expression than CIDEA+/+ T-brites (Figure S7B). In consonance with our previous finding of CIDEA's role in LD morphology (Christianson et al., 2010, Puri et al., 2008), relative to CIDEA+/+ T-brites, CIDEA−/− T-brites had reduced LD sizes after being treated with britening inducers (Figure S8A).

CIDEA KO rendered britening activators less effective at raising UCP1-dependent OCR (in the presence of a PTP inhibitor) (Figure S8B). ISO-induced proton leakage (respiratory uncoupling) was also reduced in CIDEA−/− T-brites in the presence of the PTP inhibitor (Figure S8C). Similar results were obtained in the presence of 1% BSA, which was used to mask non-specific FFA effects (Figures S8D and S8E). These results suggested that CIDEA acts as a regulator of human adipocyte britening, independent of the induction pathway triggered.

Transcriptome Analysis in Britened Human White Adipocytes in the Presence and Absence of CIDEA

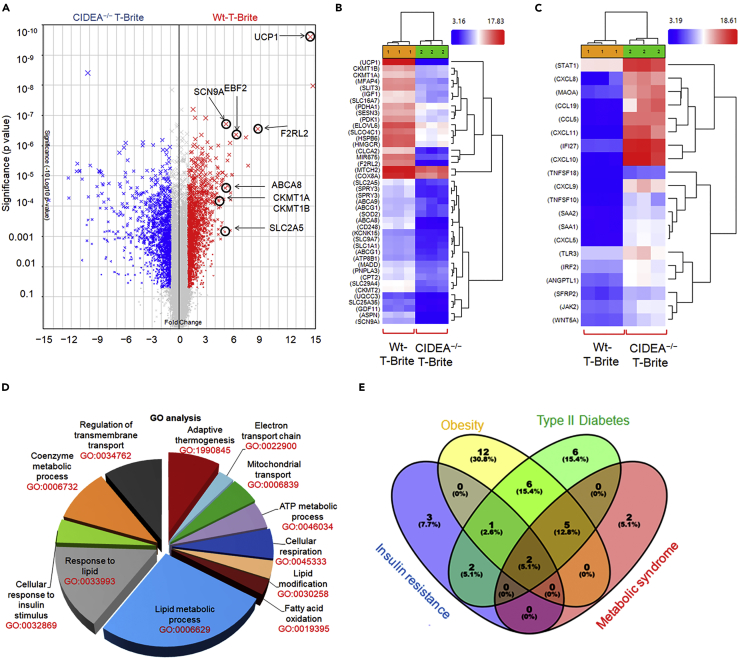

To perform transcriptome analysis, we transdifferentiated white adipocytes into brite adipocytes with a cocktail containing Rosi, FGF21, ANP, and β3 agonist. The idea was to examine the global effect of britening and thermogenic response in CIDEA−/− and CIDEA+/+ T-brites. We identified unique gene signature of brite or thermogenic genes affected by the complete absence of CIDEA (Figure 3A). Differential gene expression analysis with applied filters (ANOVA p < 0.05 and linear fold change < -2 or .2) revealed upregulation of 1,757 genes and downregulation of 1,982 genes in the CIDEA−/− T-brite adipocytes. Furthermore, expression clustering of selected highly downregulated (Figure 3B) and highly upregulated (Figure 3C) genes in the CIDEA−/− T-brites indicate CIDEA's control over thermogenic and metabolic functions. The differentially expressed genes were categorized by gene ontology analysis (GO) followed by DAVID analysis (Figure 3D). The GO analysis revealed that genes involved in overall thermogenic functions including adaptive thermogenesis (GO:1990845), fatty acid oxidation (GO:0019395), mitochondrial transport (GO:0006839), electron transport chain (GO:0022900), cellular respiration (GO:0045333), ATP metabolic process(GO:0046034), coenzyme metabolism (GO:0006732), response to lipid (GO:0033993), and response to insulin stimulation (GO:0032869) were also downregulated in the CIDEA−/− T-brite group. In addition to the downregulation of well-established gene network related to thermogenic function, CIDEA−/− T-brites showed suppression of Creatine kinase (CKMT1) expression. Recently, CkMT1-driven creatine cycle has been shown to be involved in UCP1-independent brite adipocyte thermogenic program (Kazak et al., 2015). This analysis indicated a possible role of CIDEA in thermogenesis in the brite adipocytes.

Figure 3.

A Whole-Genome Transcriptome Microarray Analysis of T-brite Adipocytes ± CIDEA

(A) Volcano plot from hierarchical clustering of differentially expressed genes in T-brite human adipocytes ± CIDEA (n = 3 in each group). Plot demonstrates a decrease in defined thermogenic (UCP1, EBF2, CKMT1A, CKMT1B) and transmembrane markers in T-brite adipocytes in the absence of CIDEA. UCP1 was most upregulated upon britening of human white adipocytes in the presence of CIDEA.

(B) Heatmap of select highly downregulated genes in T-brite adipocytes in the absence of CIDEA (Fold enrichment ≥3.8, p < 0.05).

(C) Heatmap of select highly upregulated genes in T-brite adipocytes in the absence of CIDEA (Fold enrichment ≥−4.5, p < 0.05).

(D) Pathway analysis of differentially regulated genes. Analysis of select GO terms enriched in the differentially regulated genes, downregulated in CIDEA-KO T-brites compared with the wild-type T-brites, with fold changes ≥3.85 (p < 0.05).The number on each pie slice indicates the number of genes in the respective GO terms.

(E) Venn Diagram analysis of individual GAD disease gene sets (colored circles) from the corresponding downregulated (Fold enrichment ≥3.8, p < 0.05) genes in CIDEA-KO T-brites.

All Venn Diagrams were produced with Venny http://bioinfogp.cnb.csic.es/tools/venny/index.html. The numbers on the Venn diagram indicate the number of genes shared or unshared between the indicated disease.

Next, we categorized the highly downregulated gene sets in CIDEA−/− T-brite adipocytes to the human genetic association database (GAD) to identify the significance of CIDEA in beige adipocyte function with the related metabolic disease. GAD primarily links common complex human disease rather than rare Mendelian inheritance in man (OMIM). GAD analysis indicated common metabolic disease linked to highly downregulated genes in CIDEA−/− T-brite adipocytes. Venn diagram comparison among related GAD disease showed modest gene sharing as shown in Figure 3E. This disease-related sharing at the gene level suggests a common regulatory mechanism governing britening/thermogenesis, obesity, insulin resistance, type II diabetes, and metabolic syndrome. Interestingly, CIDEA polymorphism is well connected with metabolic syndrome in humans (Dahlman et al., 2005, Nordstrom et al., 2005, Wu et al., 2013, Zhang et al., 2008). Indeed, a recent study showed that human-CIDEA specifically expressed in mouse adipose tissue improves whole-body metabolic phenotype (Abreu-Vieira et al., 2015).

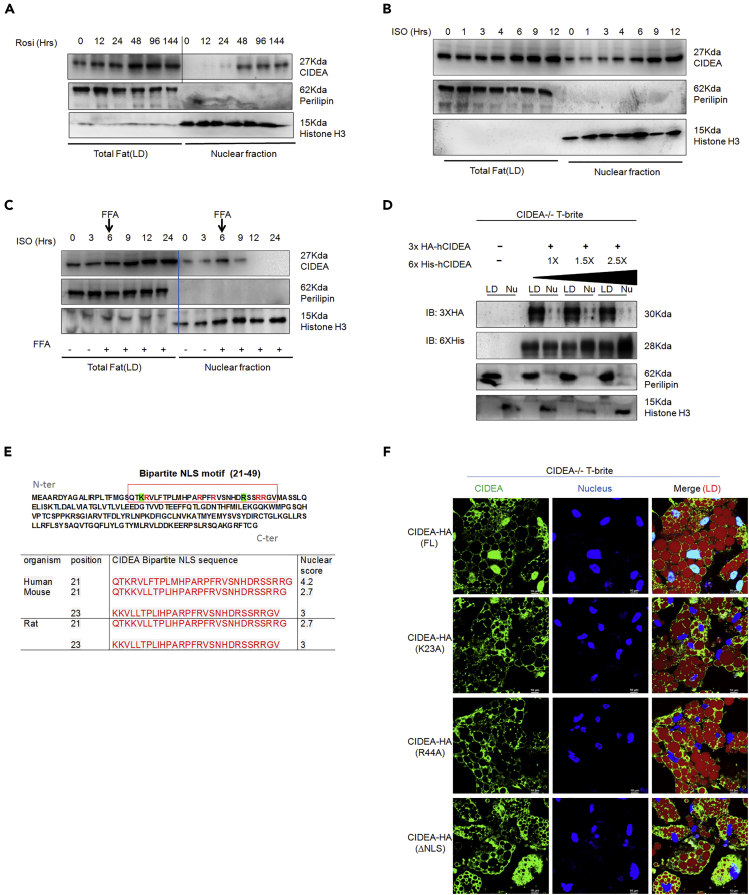

CIDEA Nuclear Localization Depends on a Bipartite Nuclear Localization Signal

CIDEA expression started increasing after 12 h upon britening induction and plateaued at 144 h (Figure S9A). Subcellular fractionation revealed nuclear localization of CIDEA beginning 24 h and peaking 48 h after britening induction (Figure 4A). Perilipin (PLIN1; negative control) remained in the lipid fraction throughout the process. Interestingly, CIDEA enrichment in the nucleus increased 5 h after ISO treatment (Figure 4B). This localization was blunted by a simultaneous cycloheximide treatment (Figure S9B). During ISO treatment, FFA/BSA blocked nuclear enrichment but enhanced CIDEA concentrations in the lipid fraction (Figure 4C). These results suggest that shuttling of CIDEA from LDs to the nucleus depends on its concentration and lipid availability. A competitive assay in which LD-associated CIDEA was saturated with 3×HA-CIDEA-mcomRNA before adding 6×His-CIDEA mcomRNA showed that, at a fixed saturable concentration of 3×HA-CIDEA, 6×His-CIDEA was enriched dose dependently in CIDEA−/− T-brite nuclei (Figure 4D). In fact, the localization of 6×His-CIDEA suggested retrograde nucleus-to-LD shuttling of CIDEA. Bipartite nuclear localization signal (NLS) mapping demonstrated that the 21–49 amino acid (aa) region of human CIDEA, which contains two basic aa clusters separated by a 21-aa spacer, has a high nuclear score of 4.0 (Figure 4E). Similar sequence in mouse and rat showed lower nuclear score. This indicates a high probability of nuclear localization of human CIDEA. Deletion of the NLS (1–219ΔNLS) or substitution of a key lysine (K23A) or arginine (R44A) disrupted CIDEA nuclear localization (Figure 4F), whereas mutation of unrelated arginines (R13A, R127A) did not (data not shown), demonstrating NLS specificity for nuclear localization. These results confirm the importance of bipartite NLS for nuclear entry of human CIDEA.

Figure 4.

Nuclear Shuttling of CIDEA

(A) Time courses of CIDEA protein expression in human white adipocytes after addition of 1 μm Rosi.

(B) Time-dependent LD versus nuclear enrichment of CIDEA after ISO-induction of T-brites.

(C) Compartmentalization of CIDEA in LDs and nuclei after albumin-bound FFA-mix challenge 6 h after ISO induction. FFA-mix (FFA/BSA) challenge inhibited CIDEA nuclear accumulation with concomitant LD enrichment.

(D) Competitive import assay showing dose-dependent nuclear enrichment of 6×His-CIDEA at fixed saturable concentration of 3×HA-CIDEA. The CIDEA−/− T-brites were transfected initially with 3×HA-CIDEA (4 μg in each of 6 wells) and then 6 h later with 6×His-CIDEA. The cells were harvested 12 h after the last transfection.

(E) Top: hCIDEA protein sequence with putative NLS at aa 21–49 (red box). Critical lysine (K23) and arginine (R44) residues are marked green; irrelevant arginines are marked red. Bottom: alignment and comparison of human bipartite NLS with mammalian analogs. Localization prediction scores were obtained from cNLS Mapper.

(F) Confocal images showing nuclear and LD localization of HA-tagged FL CIDEA and mutant CIDEA (K23A/R44A substitution or NLS deletion [ΔNLS]) in T-brites. Cells were labeled with anti-HA primary antibody followed by AF-488 secondary antibody.

We tested whether CIDEA translocation to the nucleus depends on passive diffusion through nuclear pore complexes or α/β importin-Ran-GTPase-mediated active transport. The α/β importin inhibitor ivermectin did not affect CIDEA nuclear import, indicating that it does not require active transport via α/β importin-Ran-GTPase, but blocked the import of HA-t-Ag containing a monopartite NLS recognized by α/β importin (Figure S9C). Apyrase, a nucleotide hydrolase, reduced nuclear import of CIDEA (Figure S9C). These data suggest that CIDEA nuclear entry is at least partially ATP dependent, perhaps facilitated by NLS-binding carrier molecules or may be via protein piggybacking.

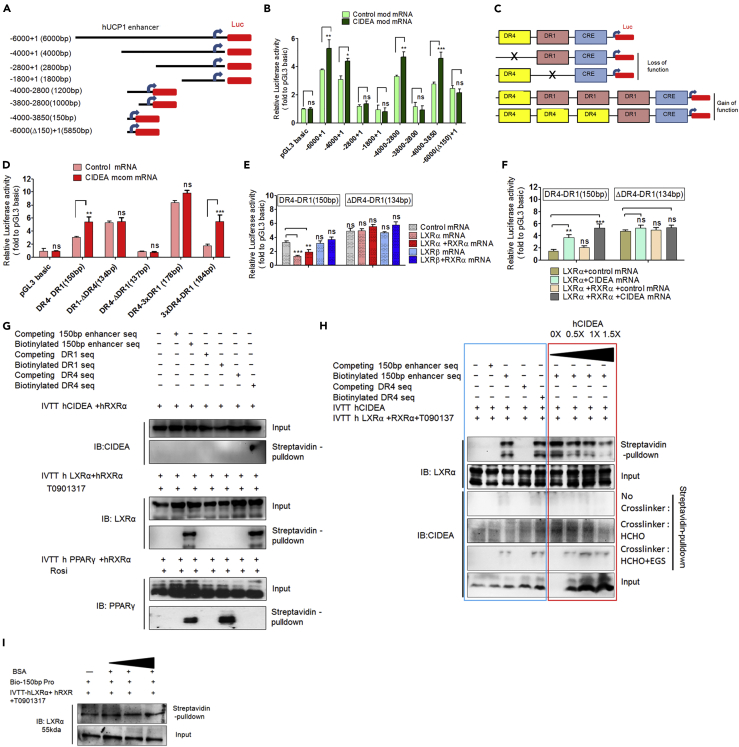

CIDEA Is a Transcriptional Activator of UCP1 during Britening

We next identified the region of UCP1 promoter/enhancer associated with CIDEA-mediated regulation of UCP1 transcription. Experiments with various luciferase-UCP1 constructs (Figure 5A) showed that the 150-bp proximal minimal region of the UCP1 distal enhancer was crucial for CIDEA-mediated upregulation of UCP1 distal enhancer activity (Figure 5B). Interestingly, this region contains previously characterized DR4 and DR1 sequences; LXR binds DR4 to downregulate UCP1 expression, whereas PPARγ binds DR1 to upregulate UCP1 expression (Juge-Aubry et al., 1997, Wang et al., 2008). Therefore, to examine whether CIDEA-mediated UCP1 regulation depends on the DR1 or DR4 sequences, we generated DR1 and DR4 loss of function mutation on 150 bp proximal enhancer sequence (Figure 5C; top three rows). Addition of CIDEA mcomRNA activated the intact minimal distal enhancer (Figure 5D, DR4-DR1). Deletion of DR1 abrogated enhancer activity completely, whereas deletion of DR4 increased enhancer activity, independent of exogenous CIDEA (Figure 5D), suggesting that DR4-LXR binding might mediate CIDEA upregulation of UCP1. To further delineate the association of CIDEA with the DR4 element, we generated gain-of-function mutants of DR1 and DR4 elements. We speculated that increased number of DR1 or DR4 would enhance the binding of LXRα and PPARγ, respectively. Therefore, we generated two separate 150-bp LUC constructs, one containing three DR4 (3xDR4) with one DR1 element (1xDR1) and other containing three DR1 (3xDR1) with one DR4 element (Figure 5C; botom two rows).Transfection of 3xDR1:1xDR4 construct resulted in a profound increase in enhancer activity independent of CIDEA, whereas 3xDR4:1xDR1 had no effect on basal enhancer activity, but it robustly responded to exogenous CIDEA (Figure 5D). These results suggest that CIDEA-mediated UCP1 upregulation occurs via DR4, a sequence known to bind LXR to negatively regulate UCP1 expression (Wang et al., 2008).

Figure 5.

CIDEA Regulates UCP1 Transcription during Human Adipocyte Britening

(A) hUCP1-Luc-pGL-3 constructs, including WT (−6,000 to +1) and seven deletion mutant constructs.

(B) Relative luciferase (rLUC) activity of each construct in response to exogenous CIDEA (12 h after transfection of mcom-CIDEA). Constructs were transfected into T-brites 24 h before transfection of mcom-CIDEA (0.750 pg/cell) or control (glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase [GAPDH]; 0.750 pg/cell) mRNA.

(C) Synthetic dUER150bp constructs containing DR1 (PPARγ-binding site) or DR4 (LXR-binding site) were cloned into a pGL-3 LUC vector for functional analysis.

(D) CIDEA (0.750 pg/cell) induction of the UCP1 promotor (150-bp WT, DR1–DR4); the ΔDR1 and ΔDR4 mutations disrupted CIDEA induction in opposite manner.

(E) Exogenous LXRα or LXRα+RXRα mRNA but not LXRβ or LXRβ+RXRα mRNA (all mRNAs: 0.750 pg/cell) suppressed expression of synthetic dUER150bp luciferase construct containing WT DR4 (DR4-DR1); this suppression was abolished with mutant DR4 (ΔDR4-DR1).

(F) Effect of exogenous mcom-CIDEA mRNA on rLUC of dUER150bp construct. T-brites were transfected with WT or mutant DR4 luciferase constructs 24 h before transfection with CIDEA mRNA (0.750 pg/cell).

(G) In vitro biotin-streptavidin DNA pull-down assay for protein-DNA interaction strength assessment of in vitro translated human recombinant (r)CIDEA, rLXRα, and rPPARγ to dUER150bp or a DR1 or DR4 oligonucleotide. LXRα and PPARγ heterodimeric partner RXRα and their respective ligands were added to facilitate DNA binding. Unlike rLXR and rPPAR, no rCIDEA was pulled down with an equivalent amount of biotinylated DNA as detected by western blotting.

(H) Protein-DNA binding analysis of rCIDEA with dUER150bp and DR4 in the presence of rLXRα and RXRα (blue box). Interaction strength of rLXRα with dUER150bp was reduced with increasing rCIDEA concentration (red box). No CIDEA was recovered by streptavidin pull down followed by western blotting in the absence of a cross-linker. HCHO + EGS cross-linking, but not HCHO-only cross-linking, pulled down CIDEA, revealing a distant CIDEA-LXRα interaction.

(I) Progressive addition of BSA (negative control) did not affect LXRα-DR4 interaction.

In (B), (D), (E), and (F), data are mean rLUC (relative to pGL-3 basic vector) ± SEM (n = 3). ***p < 0.001, **p < .01, and *p < .05; two-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni post tests.

We next measured UCP1 enhancer activity in the presence of LXRα or LXRβ alone or with their obligatory heterodimeric partner RXRα. Exogenous LXRα, but not LXRβ, suppressed UCP1 enhancer activity, consistent with a previous study demonstrating similar selectivity in mice (Wang et al., 2008), and this effect was absent with the deleted-DR4 construct (Figure 5E). Importantly, CIDEA along with LXRα alone or with its obligatory heterodimeric partner RXRα countered this LXRα-mediated suppression of UCP1 enhancer activity (Figure 5F). LXRα agonism with T0901317 reduced UCP1 mRNA expression in CIDEA−/− T-brites with or without ISO but only with ISO in CIDEA+/+ T brites (Figure S10A). Similar results were obtained with GW3965, another LXR agonist (data not shown). We attempted to study the effect of CIDEA by knocking out LXRα by CRISPR, but the LXRα knockout cells did not grow well, showing that LXRα might also have a role in cellular growth and/or development. Therefore, we used small interfering RNA (siRNA) to knock down LXRs. siRNA-mediated knockdown of LXRα, but not LXRβ, increased UCP1 protein expression in T-brites, indicating that LXRβ does not regulate UCP1 expression and also may not compensate for LXRα (Figure S10B). Moreover, uncoupled respiration was increased in LXRα-, but not LXRβ-, depleted T-brites, independent of CIDEA (Figure S10C). Overall, our observations indicate that CIDEA affects UCP1 transcription via LXRα.

CIDEA-LXR Dynamics Is Key to UCP1 Transcriptional Regulation

To test whether CIDEA has any direct interaction with UCP1 enhancer region, we performed in vitro biotinylated-DNA pull-down assays coupled with immunoblots. As shown in Figure 5G, CIDEA did not bind the 150-bp UCP1 distal enhancer region (dUER150bp), nor the DR1 or DR4 oligonucleotides, even in the presence of the LXRα heterodimeric partner RXRα (Figure 5G; top blots). Subsequent assays were performed in the presence of RXRα and the LXRα agonist, T0901317. LXRα (Figure 5G; middle blots) and PPARγ (Figure 5G; lower blots) bound their cognate sequences as efficiently as they bound dUER150bp.

Streptavidin pull-down assays of biotinylated dUER150bp, DR4, or DR1 sequences did not recover any CIDEA in the presence of LXRα or PPARγ (Figure 5H, blue box), suggesting that CIDEA may not bind the enhancer via LXRα or PPARγ. Unlike cross-linking with Formaldehyde (Short cross-linking spacer arm, ~2 A°), cross-linking with Formaldehyde-EGS (long spacer arm, ~16.1 A°) revealed a transient interaction of CIDEA with DR4 (Figure 5H) but not with DR1 (Figure S10D, blue box). As a positive control, biotinylated DR4 and DR1 pulled down LXRα and PPARγ, respectively (Figures 5H and S10D). Interestingly, LXRα binding with its cognate DR4 element in dUER150bp was weakened with increasing CIDEA (Figure 5H, red box), but not BSA (Figure 5I), concentrations, demonstrating the CIDEA binding specificity for LXRα. CIDEA had no effect on PPARγ binding to DR1 (Figure S10D; red square). PPARγ and its ligand rosiglitazone did not affect CIDEA-mediated inhibition of LXRα-DR4 binding (Figure S10E). Overall, the above-mentioned results show that CIDEA interacts with LXRα, which weakens LXRα binding to DR4.

CIDEA Directly Binds to LXRα and Weakens Its Binding to UCP1 Enhancer

To further test that CIDEA weakens LXRα binding to DR4, we produced a single-nucleotide (T-G) mutation one nucleotide before the DR4 core sequence, resulting in an AatII restriction site outside of DR4 (Figure 6A). The idea was that LXRα binding to DR4 would inhibit the cleavage with AatII restriction enzyme. As expected, in the absence of LXRα, there was a cleavage with AatII restriction enzyme, which was otherwise blocked by LXRα binding (Figure 6B). Interestingly, when this construct was incubated with LXRα, AatII cleavage of DR4 increased with increasing concentrations of CIDEA (Figure 6B; top left blot); this cleavage was unaffected by BSA (negative control; Figure 6B; bottom blot). Furthermore, the mutant DR4 fragment did not bind LXRα and was cleaved completely, even in the presence of LXRα, indicating that LXRα protects the DR4 element from cleavage (Figure 6B; top right blot). To further confirm, pull-down assays of nuclear lysates followed by LXRα and CIDEA immunoblots showed that CIDEA−/− T-brites recovered more LXRα than CIDEA+/+ T-brites (Figure 6C) and that this increase was suppressed upon CIDEA re-expression (Figure 6C; far right lane). These results confirmed that CIDEA binding to LXRα results in its removal from the UCP1 enhancer releasing LXRα inhibition of UCP1 transcription. On the other hand, PPARγ recovery was reduced in CIDEA−/− T-brites but recovered upon re-expression of CIDEA (Figure 6C), suggesting that CIDEA positively regulates PPARγ binding to the UCP1 enhancer.

A previous study reported that CIDEA interacts with liver X receptors in white fat cells (Kulyte et al., 2011). We studied if there is a direct interaction of CIDEA with LXRα in brite adipocytes. Bidirectional co-immunoprecipitation (coIP) of CIDEA with LXRα (Figure 6D) suggested a physical interaction between these two proteins. Addition of the LXR ligand increased CIDEA coIP with LXRα, without any effect on LXRα IP (Figure 6D).

In vitro transcription and translation (IVTT)-coupled coIP immunoblot assays confirmed direct interaction of CIDEA with LXRα (Figure 6D); GFP did not bind either protein. These results showed that CIDEA interacts directly with LXRα. Furthermore, in situ proximity ligation assays (PLAs) demonstrated that CIDEA KO abolished the strong association between CIDEA and LXR (Figure 6E).

Based on the above-mentioned results, we then tested a hypothesis that increased CIDEA in the nucleus during britening of white adipocytes affects LXRα occupancy at the UCP1 enhancer. Indeed, ChIP-qPCR for LXRα showed decreased recovery of UCP1 enhancer-associated LXRα over the 2 days following induction of britening, in CIDEA+/+ (Figure 6F) but not CIDEA−/− cells (Figure 6G). Similar results were obtained in the presence of LXR ligand (Figure S11A). CIDEA re-expression reduced LXR association with the UCP1 enhancer within 24 h in CIDEA−/− cells (Figure 6H), and this LXRα association with the enhancer recovered as the transient ectopic CIDEA re-expression subsided with time (Figures 6H and 1D).

Analysis of the UCP1 promoter-enhancer suggested six additional putative LXR response elements (Figure S11B) (Hong and Tontonoz, 2014). Functionality testing showed that, other than DR4 at −3,903, none of these were critical for LXRα binding of the UCP1 promoter-enhancer (Figure S11C).

Since LXRα is known to control a variety of genes in metabolic organs, we next studied if CIDEA-LXRα specifically regulates UCP1.We performed qRT-PCR and ChIP analysis on LXRα-regulated genes in T-brite adipocytes ± CIDEA (Figure S12A). As shown in Figure S12B, except for GLUT4 and APOD none of the LXR-regulated genes showed any significant effect of CIDEA. This observation is in line with a study showing increase in GLUT4 expression in human brown adipocytes along with UCP1 and CIDEA, which makes human brown adipocytes more glucose responsive (Lee et al., 2016).

Discussion

Various studies have shown a positive association of CIDEA expression with healthy metabolic phenotype in humans (Dahlman et al., 2005, Feldo et al., 2013, Gummesson et al., 2007, Nordstrom et al., 2005, Puri et al., 2008, Wu et al., 2013, Zhang et al., 2008). Our present study deciphers a comprehensive cellular and molecular mechanism of CIDEA in the regulation of improved metabolism via regulating thermogenesis and britening by transcriptional regulation of UCP1 in humans (Figure 6I). Our results show that LXRα is the functional interactor of CIDEA, whereby CIDEA represses its activity on UCP1 enhancer. In this work, we first developed dual-RNA based CRISPR-Cas9 and modified-RNA methodologies to modulate CIDEA expression efficiently in cultured human primary adipocytes derived from hADSCs. The T-brite phenotype was confirmed by heightened thermogenic capacity and expression of brite/beige adipocyte markers (Kajimura et al., 2015). Importantly, our experiments demonstrated that CIDEA leads to britening of human adipocytes via transcriptional regulation of UCP1, wherein CIDEA interacts directly with LXRα, thereby weakening LXRα binding to the UCP1 enhancer. Our results were supported by a previous study that showed that CIDEA binds to LXRs and regulates their activity in human white adipocytes (Kulyte et al., 2011). Also, the propensity for UCP1 induction in human adipocytes has been shown to be correlated with CIDEA levels and withdrawal of thermogenic induction led rapidly to instability of CIDEA protein and UCP1 mRNA in vivo (Rosenwald et al., 2013) and in vitro (data not shown). Reintroducing CIDEA into CIDEA−/− cells rescued fully functional T-brite formation, as well as a correlation between CIDEA levels and increased UCP1 transcription and activity. This work defines a crucial role of CIDEA in regulating the brite phenotype in human adipocytes.

In rodents, UCP1 transcription is regulated largely by a combined effect of the CREreach proximal segment and a strong enhancer region ~2.5 kb upstream of the transcription start site; in humans, this region is ~3.9 kb upstream of the transcription start site. Additionally, the human proximal promoter region has more CpG islands than in the mouse (human ENCOD database). Our analysis showed that a 150-bp distal enhancer region (−4,000 to −3,058) of human UCP1 is DNase 1 hypersensitive, indicating multiple transcription factor-binding sites and suggesting that the mechanisms regulating UCP1 transcription may differ between humans and mice. In fact, ISO-mediated UCP1 transcription is weaker in humans than in rodents (del Mar Gonzalez-Barroso et al., 2000). Surprisingly, CIDEA regulation of UCP1 was indirect via a long loop interaction with LXRα. Although CIDEA interacts physically with both LXRα and LXRβ (data not shown), our data indicate that only CIDEA-LXRα interactions are crucial for UCP1 transcription, perhaps owing to its relatively greater stability. It is possible that CIDEA might remove LXRα from DR4, thereby helping PPARγ to regain control over limiting amounts of RXRα, a heterodimeric partner crucial for LXRα and PPARγ activity.

During adipocyte britening, CIDEA was shuttled to the nucleus via its bipartite NLS, independent of active transport and the classical α/β importin pathway. Notably, we incorporated HA tags into the mutants to keep the CIDEA molecule small enough for passive diffusion (Timney et al., 2016). We hypothesize that specific amino acids in the bipartite NLS may interact with nuclear pore proteins during passive diffusion to overcome a steep concentration gradient. These nuclear pore proteins may influence the passive diffusion rate.

CIDEA knockout mice were reported to have a lean phenotype and resistance to diet-induced obesity. It was explained on the basis of reduced UCP1 activity by CIDEA by physically interacting with it in mitochondria (Wu et al., 2014), although later studies showed that CIDEA is not localized in adipocyte mitochondria (Christianson et al., 2010, Puri et al., 2008, Wang et al., 2012). These seemingly disparate results in CIDEA function might also be due to increased lipolysis in whole-body CIDEA-knockout mouse, which produces excessive intracellular FFAs that might cause increased respiration through non-specific protonophoric FFA actions and PTP opening (Li et al., 2014) resulting in increased thermogenicity. A recent study showed that, in adipose-specific CIDEA transgenic mouse, CIDEA adipose expression is proportional to tissue briteness and UCP1 expression was increased owing to adipocyte hyper-recruitment from a mixed adipose tissue (Fischer et al., 2017). Given our observation that robust UCP1 expression precedes brite-adipocyte specific gene expression during britening, we hypothesize that CIDEA-mediated de-repression of UCP1 could create mitochondrion-derived retrograde signaling to the nucleus for complete transdifferentiation of adipocytes into T-brites. It is also possible that inhibition of LXRα suppression by CIDEA could affect a broader network of genes, beyond UCP1, that drive adipocyte britening. For example, our observation of reduced DIO2 (type II iodothyronine deiodinase) expression in CIDEA−/− adipocytes may be relevant for thermogenesis and britening given that thyroid hormones have been linked with brown adipocyte formation and thermogenesis in mice via DIO2 upregulation (Weiner et al., 2016).

During thermogenic stimulation by PPARγ or cAMP (Chen et al., 2013), LXRα is recruited to the UCP1 enhancer (Wang et al., 2008). Our study showed that both of these conditions augmented CIDEA expression and CIDEA enrichment in the nucleus. It is notable that UCP1 transcription was decreased by nearly half but not completely abolished in our CIDEA−/− cells. Potential explanations for this remaining UCP1 transcription include initial dismissal of LXRα by PPARγ enabling basal UCP1 transcription, CRE downstream of the PPAR response element activating UCP1 transcription, and/or Rosi initiating a PPARγ-independent B38/mitogen-activated protein kinase phosphorylation cascade. Our time course ChIP analysis indicated that CIDEA was involved in the maintenance and robustness of UCP1 transcription, rather than its initiation, during adipocyte britening.

CIDEA does not influence the chromatin retention of LXRα but rather interacts with it to alter its localized repressor activity on UCP1. Since CIDEA is a multifunctional protein, we performed a comprehensive transcriptome analysis in britened human white adipocytes ± CIDEA. As shown in Figure 3, UCP1 was the most upregulated gene in T-brite adipocytes. In conclusion, this study established a previously unidentified role of CIDEA in the transcriptional regulation of thermogenesis in human adipocytes and their britening.

Limitations of the Study

Our study defines the molecular role of CIDEA as a regulator of thermogenesis in human adipocytes. We have shown that CIDEA directly binds to LXRα and repress its activity on UCP1 enhancer. Although this study identified the role of CIDEA as a regulator of thermogenesis in human primary adipocytes, its in vivo role in humans remains to be proven. Presently, our results demonstrate that, during britening of human adipocytes, CIDEA expression is increased resulting in translocation to the nucleus via a bipartite NLS. Future studies are required to identify the NLS-binding molecules that may facilitate the entry of CIDEA into the nucleus.

Methods

All methods can be found in the accompanying Transparent Methods supplemental file.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH/NIDDK grants DK101711 (VP) and R56DK094815 (VP). Dr. Puri received support through the Osteopathic Heritage Foundation’s Vision 2020: Leading the Transformation of Primary Care in Ohio award to the Heritage College of Osteopathic Medicine at Ohio University.

Author Contributions

S.J. contributed to study design, performing experiments, analysis of results, and manuscript preparation. S.B. aided in experiments and manuscript preparation. M.-J.L. provided human tissue samples and contributed to data analysis. S.R.F. contributed to study design. V.P. contributed to study design and oversight, analysis of results, and manuscript preparation.

Declaration of Interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Published: October 25, 2019

Footnotes

Supplemental Information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isci.2019.09.011.

Data and Code Availability

The mRNA template sequences and their Gene Bank accession number is provided in the Data S1 dataset file.

Supplemental Information

Following is a list of all the genes, their primer IDs, primer sequences, and purpose.

References

- Abreu-Vieira G., Fischer A.W., Mattsson C., de Jong J.M., Shabalina I.G., Ryden M., Laurencikiene J., Arner P., Cannon B., Nedergaard J. CIDEA improves the metabolic profile through expansion of adipose tissue. Nat. Commun. 2015;6:7433. doi: 10.1038/ncomms8433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmadian M., Abbott M.J., Tang T., Hudak C.S., Kim Y., Bruss M., Hellerstein M.K., Lee H.Y., Samuel V.T., Shulman G.I. Desnutrin/ATGL is regulated by AMPK and is required for a brown adipose phenotype. Cell Metab. 2011;13:739–748. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2011.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barneda D., Frontini A., Cinti S., Christian M. Dynamic changes in lipid droplet-associated proteins in the “browning” of white adipose tissues. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2013;1831:924–933. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2013.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barneda D., Planas-Iglesias J., Gaspar M.L., Mohammadyani D., Prasannan S., Dormann D., Han G.S., Jesch S.A., Carman G.M., Kagan V. The brown adipocyte protein CIDEA promotes lipid droplet fusion via a phosphatidic acid-binding amphipathic helix. Elife. 2015;4:e07485. doi: 10.7554/eLife.07485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bordicchia M., Liu D., Amri E.Z., Ailhaud G., Dessi-Fulgheri P., Zhang C., Takahashi N., Sarzani R., Collins S. Cardiac natriuretic peptides act via p38 MAPK to induce the brown fat thermogenic program in mouse and human adipocytes. J. Clin. Invest. 2012;122:1022–1036. doi: 10.1172/JCI59701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H.Y., Liu Q., Salter A.M., Lomax M.A. Synergism between cAMP and PPARgamma signalling in the initiation of UCP1 gene expression in HIB1B brown Adipocytes. PPAR Res. 2013;2013:476049. doi: 10.1155/2013/476049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christianson J.L., Boutet E., Puri V., Chawla A., Czech M.P. Identification of the lipid droplet targeting domain of the CIDEA protein. J. Lipid Res. 2010;51:3455–3462. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M009498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahlman I., Kaaman M., Jiao H., Kere J., Laakso M., Arner P. The CIDEA gene V115F polymorphism is associated with obesity in Swedish subjects. Diabetes. 2005;54:3032–3034. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.10.3032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- del Mar Gonzalez-Barroso M., Pecqueur C., Gelly C., Sanchis D., Alves-Guerra M.C., Bouillaud F., Ricquier D., Cassard-Doulcier A.M. Transcriptional activation of the human ucp1 gene in a rodent cell line. Synergism of retinoids, isoproterenol, and thiazolidinedione is mediated by a multipartite response element. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:31722–31732. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M001678200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldo M., Kocki J., Lukasik S., Bogucki J., Feldo J., Terlecki P., Kesik J., Wronski J., Zubilewicz T. CIDE–A gene expression in patients with abdominal obesity and LDL hyperlipoproteinemia qualified for surgical revascularization in chronic limb ischemia. Pol. Przegl. Chir. 2013;85:644–648. doi: 10.2478/pjs-2013-0097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer A.W., Shabalina I.G., Mattsson C.L., Abreu-Vieira G., Cannon B., Nedergaard J., Petrovic N. UCP1 inhibition in CIDEA-overexpressing mice is physiologically counteracted by brown adipose tissue hyperrecruitment. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2017;312:E72–E87. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00284.2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher F.M., Kleiner S., Douris N., Fox E.C., Mepani R.J., Verdeguer F., Wu J., Kharitonenkov A., Flier J.S., Maratos-Flier E. FGF21 regulates PGC-1alpha and browning of white adipose tissues in adaptive thermogenesis. Genes Dev. 2012;26:271–281. doi: 10.1101/gad.177857.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghorbani M., Himms-Hagen J. Appearance of brown adipocytes in white adipose tissue during CL 316,243-induced reversal of obesity and diabetes in Zucker fa/fa rats. Int. J. Obes. Relat. Metab. Disord. 1997;21:465–475. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0800432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grahn T.H., Kaur R., Yin J., Schweiger M., Sharma V.M., Lee M.J., Ido Y., Smas C.M., Zechner R., Lass A. Fat-specific protein 27 (FSP27) interacts with adipose triglyceride lipase (ATGL) to regulate lipolysis and insulin sensitivity in human adipocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 2014;289:12029–12039. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.539890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granneman J.G., Li P., Zhu Z., Lu Y. Metabolic and cellular plasticity in white adipose tissue I: effects of beta3-adrenergic receptor activation. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2005;289:E608–E616. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00009.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gummesson A., Jernas M., Svensson P.A., Larsson I., Glad C.A., Schele E., Gripeteg L., Sjoholm K., Lystig T.C., Sjostrom L. Relations of adipose tissue CIDEA gene expression to basal metabolic rate, energy restriction, and obesity: population-based and dietary intervention studies. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2007;92:4759–4765. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-1136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harms M., Seale P. Brown and beige fat: development, function and therapeutic potential. Nat. Med. 2013;19:1252–1263. doi: 10.1038/nm.3361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiraike Y., Waki H., Yu J., Nakamura M., Miyake K., Nagano G., Nakaki R., Suzuki K., Kobayashi H., Yamamoto S. NFIA co-localizes with PPARgamma and transcriptionally controls the brown fat gene program. Nat. Cell Biol. 2017;19:1081–1092. doi: 10.1038/ncb3590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong C., Tontonoz P. Liver X receptors in lipid metabolism: opportunities for drug discovery. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2014;13:433–444. doi: 10.1038/nrd4280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juge-Aubry C., Pernin A., Favez T., Burger A.G., Wahli W., Meier C.A., Desvergne B. DNA binding properties of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor subtypes on various natural peroxisome proliferator response elements. Importance of the 5'-flanking region. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:25252–25259. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.40.25252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kajimura S., Spiegelman B.M., Seale P. Brown and beige fat: physiological roles beyond heat generation. Cell Metab. 2015;22:546–559. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2015.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazak L., Chouchani E.T., Jedrychowski M.P., Erickson B.K., Shinoda K., Cohen P., Vetrivelan R., Lu G.Z., Laznik-Bogoslavski D., Hasenfuss S.C. A creatine-driven substrate cycle enhances energy expenditure and thermogenesis in beige fat. Cell. 2015;163:643–655. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.09.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulyte A., Pettersson A.T., Antonson P., Stenson B.M., Langin D., Gustafsson J.A., Staels B., Ryden M., Arner P., Laurencikiene J. CIDEA interacts with liver X receptors in white fat cells. FEBS Lett. 2011;585:744–748. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2011.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laurencikiene J., Stenson B.M., Arvidsson Nordstrom E., Agustsson T., Langin D., Isaksson B., Permert J., Ryden M., Arner P. Evidence for an important role of CIDEA in human cancer cachexia. Cancer Res. 2008;68:9247–9254. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-1343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee M.J., Pickering R.T., Puri V. Obesity; 2013. Prolonged Efficiency of siRNA-Mediated Gene Silencing in Primary Cultures of Human Preadipocytes and Adipocytes. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee M.J., Wu Y., Fried S.K. Obesity; 2012. A Modified Protocol to Maximize Differentiation of Human Preadipocytes and Improve Metabolic Phenotypes. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee P., Bova R., Schofield L., Bryant W., Dieckmann W., Slattery A., Govendir M.A., Emmett L., Greenfield J.R. Brown adipose tissue exhibits a glucose-responsive thermogenic biorhythm in humans. Cell Metab. 2016;23:602–609. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2016.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y., Fromme T., Schweizer S., Schottl T., Klingenspor M. Taking control over intracellular fatty acid levels is essential for the analysis of thermogenic function in cultured primary brown and brite/beige adipocytes. EMBO Rep. 2014;15:1069–1076. doi: 10.15252/embr.201438775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald M.E., Li C., Bian H., Smith B.D., Layne M.D., Farmer S.R. Myocardin-related transcription factor A regulates conversion of progenitors to beige adipocytes. Cell. 2015;160:105–118. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nedergaard J., Bengtsson T., Cannon B. Unexpected evidence for active brown adipose tissue in adult humans. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2007;293:E444–E452. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00691.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nedergaard J., Cannon B. The changed metabolic world with human brown adipose tissue: therapeutic visions. Cell Metab. 2010;11:268–272. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2010.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nedergaard J., Cannon B. How brown is brown fat? It depends where you look. Nat. Med. 2013;19:540–541. doi: 10.1038/nm.3187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nordstrom E.A., Ryden M., Backlund E.C., Dahlman I., Kaaman M., Blomqvist L., Cannon B., Nedergaard J., Arner P. A human-specific role of cell death-inducing DFFA (DNA fragmentation factor-alpha)-like effector A (CIDEA) in adipocyte lipolysis and obesity. Diabetes. 2005;54:1726–1734. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.6.1726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohno H., Shinoda K., Spiegelman B.M., Kajimura S. PPARgamma agonists induce a white-to-brown fat conversion through stabilization of PRDM16 protein. Cell Metab. 2012;15:395–404. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2012.01.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puri V., Konda S., Ranjit S., Aouadi M., Chawla A., Chouinard M., Chakladar A., Czech M.P. Fat-specific protein 27, a novel lipid droplet protein that enhances triglyceride storage. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:34213–34218. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M707404200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puri V., Ranjit S., Konda S., Nicoloro S.M., Straubhaar J., Chawla A., Chouinard M., Lin C., Burkart A., Corvera S. Cidea is associated with lipid droplets and insulin sensitivity in humans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2008;105:7833–7838. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0802063105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiang L., Wang L., Kon N., Zhao W., Lee S., Zhang Y., Rosenbaum M., Zhao Y., Gu W., Farmer S.R. Brown remodeling of white adipose tissue by SirT1-dependent deacetylation of Ppargamma. Cell. 2012;150:620–632. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.06.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds T.H.t., Banerjee S., Sharma V.M., Donohue J., Couldwell S., Sosinsky A., Frulla A., Robinson A., Puri V. Effects of a high fat diet and voluntary wheel running exercise on cidea and CIDEC expression in liver and adipose tissue of mice. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0130259. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0130259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenwald M., Perdikari A., Rulicke T., Wolfrum C. Bi-directional interconversion of brite and white adipocytes. Nat. Cell Biol. 2013;15:659–667. doi: 10.1038/ncb2740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seale P., Bjork B., Yang W., Kajimura S., Chin S., Kuang S., Scime A., Devarakonda S., Conroe H.M., Erdjument-Bromage H. PRDM16 controls a brown fat/skeletal muscle switch. Nature. 2008;454:961–967. doi: 10.1038/nature07182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seale P., Kajimura S., Yang W., Chin S., Rohas L.M., Uldry M., Tavernier G., Langin D., Spiegelman B.M. Transcriptional control of brown fat determination by PRDM16. Cell Metab. 2007;6:38–54. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2007.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh M., Kaur R., Lee M.J., Pickering R.T., Sharma V.M., Puri V., Kandror K.V. Fat-specific protein 27 inhibits lipolysis by facilitating the inhibitory effect of transcription factor Egr1 on transcription of adipose triglyceride lipase. J. Biol. Chem. 2014;289:14481–14487. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C114.563080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timney B.L., Raveh B., Mironska R., Trivedi J.M., Kim S.J., Russel D., Wente S.R., Sali A., Rout M.P. Simple rules for passive diffusion through the nuclear pore complex. J. Cell Biol. 2016;215:57–76. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201601004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vernochet C., McDonald M.E., Farmer S.R. Brown adipose tissue: a promising target to combat obesity. Drug News Perspect. 2010;23:409–417. doi: 10.1358/dnp.2010.23.7.1487083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vernochet C., Peres S.B., Davis K.E., McDonald M.E., Qiang L., Wang H., Scherer P.E., Farmer S.R. C/EBPalpha and the corepressors CtBP1 and CtBP2 regulate repression of select visceral white adipose genes during induction of the brown phenotype in white adipocytes by peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma agonists. Mol. Cell Biol. 2009;29:4714–4728. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01899-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H., Liu L., Lin J.Z., Aprahamian T.R., Farmer S.R. Browning of white adipose tissue with Roscovitine induces a distinct population of UCP1+ Adipocytes. Cell Metab. 2016;24:835–847. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2016.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H., Zhang Y., Yehuda-Shnaidman E., Medvedev A.V., Kumar N., Daniel K.W., Robidoux J., Czech M.P., Mangelsdorf D.J., Collins S. Liver X receptor alpha is a transcriptional repressor of the uncoupling protein 1 gene and the brown fat phenotype. Mol. Cell Biol. 2008;28:2187–2200. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01479-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W., Lv N., Zhang S., Shui G., Qian H., Zhang J., Chen Y., Ye J., Xie Y., Shen Y. CIDEA is an essential transcriptional coactivator regulating mammary gland secretion of milk lipids. Nat. Med. 2012;18:235–243. doi: 10.1038/nm.2614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiner J., Kranz M., Kloting N., Kunath A., Steinhoff K., Rijntjes E., Kohrle J., Zeisig V., Hankir M., Gebhardt C. Thyroid hormone status defines brown adipose tissue activity and browning of white adipose tissues in mice. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:38124. doi: 10.1038/srep38124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu J., Zhang L., Zhang J., Dai Y., Bian L., Song M., Russell A., Wang W. The genetic contribution of CIDEA polymorphisms, haplotypes and loci interaction to obesity in a Han Chinese population. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2013;40:5691–5699. doi: 10.1007/s11033-013-2671-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu L., Zhou L., Chen C., Gong J., Xu L., Ye J., Li D., Li P. Cidea controls lipid droplet fusion and lipid storage in brown and white adipose tissue. Sci. China Life Sci. 2014;57:107–116. doi: 10.1007/s11427-013-4585-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L., Miyaki K., Nakayama T., Muramatsu M. Cell death-inducing DNA fragmentation factor alpha-like effector A (CIDEA) gene V115F (G-->T) polymorphism is associated with phenotypes of metabolic syndrome in Japanese men. Metabolism. 2008;57:502–505. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2007.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Z., Yon Toh S., Chen Z., Guo K., Ng C.P., Ponniah S., Lin S.C., Hong W., Li P. CIDEA-deficient mice have lean phenotype and are resistant to obesity. Nat. Genet. 2003;35:49–56. doi: 10.1038/ng1225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Following is a list of all the genes, their primer IDs, primer sequences, and purpose.

Data Availability Statement

The mRNA template sequences and their Gene Bank accession number is provided in the Data S1 dataset file.