Abstract

Thrombin is an enzyme that plays many important roles in the blood clotting process; it activates platelets, cleaves coagulation proteins within feedback loops, and cleaves fibrinogen into fibrin, which polymerizes into fibers to form a stabilizing gel matrix in and around growing clots. Thrombin also binds to the formed fibrin matrix, but this interaction is not well understood. Thrombin-fibrin binding is often described as two independent, single-step binding events, one high-affinity and one low-affinity. However, kinetic schemes describing these single-step binding events do not explain experimentally-observed residency times of fibrin-bound thrombin. In this work, we study a bivalent, sequential-step binding scheme as an alternative to the high-affinity event and, in addition to the low-affinity one. We developed mathematical models for the single- and sequential-step schemes consisting of reaction-diffusion equations to compare to each other and to experimental data. We then used Bayesian inference, in the form of Markov chain Monte Carlo, to learn model parameter distributions from previously published experimental data. For the model to best fit the data, we made an additional assumption that thrombin was irreversibly sequestered; we hypothesized that this could be due to thrombin becoming physically trapped within fibrin fibers as they formed. We further estimated that ∼30% of thrombin in the experiments to which we compare our model output became physically trapped. The notion of physically trapped thrombin may provide new insights into conflicting observations regarding the speed of fibrinolysis. Finally, we show that our new model can be used to further probe scenarios dealing with thrombin allostery.

Significance

It has been observed that thrombin, the major enzyme produced during blood clot formation, binds to fibrin in clots and remains stably bound for extended periods of time. The binding scheme and rate constants currently found in the literature do not explain these observations. Here, we use a bivalent binding scheme with a corresponding mathematical model and use Bayesian inference to learn parameters from previously published experimental data. To acquire the best fit with the data, we had to assume that some thrombin was irreversibly sequestered, which led to the hypothesis that thrombin can become physically trapped inside fibrin fibers during their formation. Additionally, our bivalent model allows for the study of thrombin allostery, which is important for the development of anticoagulant drugs.

Introduction

In response to an injury, blood will clot to prevent bleeding from the body. The clotting process is comprised of two intertwined subprocesses: platelet aggregation and blood coagulation. Platelet aggregation includes platelets adhering to the injured vessel and cohering with one another to form a plug that initially slows blood leakage. Blood coagulation is a biochemical system whereby dozens of enzymatic reactions occur in the blood and on the platelet surfaces and culminate in the generation of the enzyme thrombin. Thrombin then cleaves fibrinogen, yielding fibrin monomers, which then polymerize into fibers to form a stabilizing mesh in and around the platelet plug. The most well-known role for thrombin is its cleaving of fibrinogen to fibrin but it has other roles as well; it is involved in multiple positive and negative feedback loops whereby it cleaves different substrates that lead to the production and inhibition of itself, and it is also a potent activator of platelets. Another role that has recently gained attention is its binding directly to already cleaved fibrin in clots, where it has been observed to stay bound for extended periods of time (1, 2, 3). Fibrin-bound thrombin may have important clinical implications because of allosteric interactions between thrombin, fibrin, and anticoagulants (2,4,5); however, the underlying thrombin-fibrin binding mechanism(s) remain poorly characterized.

Several potential functions of clot-bound thrombin have been proposed: 1) an inhibitory one, localizing thrombin to an injury site and limiting downstream clotting (6); 2) a stabilizing one, slowing fibrinolysis (the breakdown of the fibrin mesh) (7); or 3) a pathological one, leading to unwanted thrombosis if the thrombin is released because of mechanical failure or fibrinolytic breakdown of a clot (8,9). Further, γA/γ′ fibrin(ogen), the specific type of fibrin(ogen) thought to be primarily associated with clot-bound thrombin, has recently been implicated as a potential clinical biomarker for myocardial infarctions (10), coronary artery disease (11), and deep vein thrombosis (12).

Thrombin is a serine protease with a catalytic active site flanked by two exosites, exosite 1 and exosite 2. These exosites serve to localize thrombin by binding it to various substrates and to platelet surfaces, which aids in coagulation and platelet activation (13, 14, 15, 16, 17). Fibrinogen is an insoluble plasma protein that, upon enzymatic cleavage by thrombin, becomes soluble fibrin (18). Fibrin has a dimeric structure with a central E domain flanked by two D domains; each D domain has a γ chain associated with it (19), typically found in the form of a γA chain but with roughly in what is known as the minority conformation, or γ′ chains. Because of its dimeric structure, fibrin can be classified by the amount of γ′ chains that it possesses: γA/γA fibrin(ogen) has no γ′ chains, and γA/γ′ fibrin(ogen) has one γ′ chain (19). Several experimental preparations of fibrin will be discussed in this work: wild-type fibrin, in which 15% of all γ chains are in the form of γ′; fractionated γA/γA fibrin with no γ′ chains; and fractionated γA/γ′ fibrin in which every fibrin monomer has one γA and one γ′ chain (1,20).

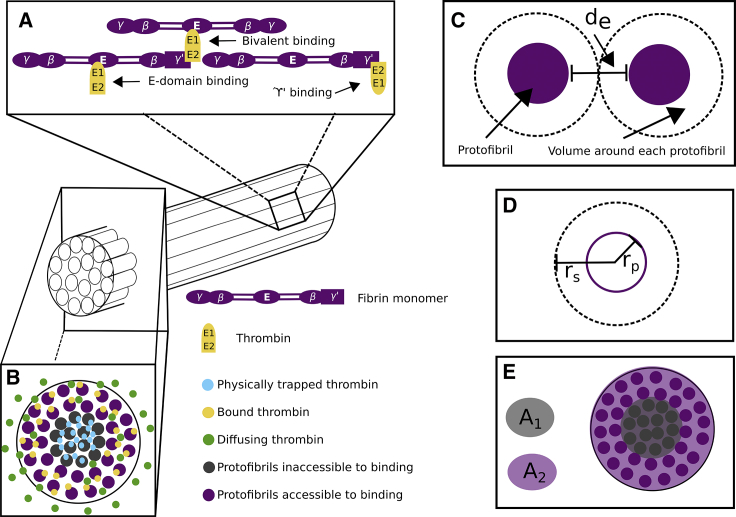

Thrombin binds at two locations on fibrin and does so with distinct exosites; it binds to sites on the central E domain via exosite 1, and it binds to sites on the γ′ chain of fibrin via exosite 2 (19,21). Thrombin binds either fibrin binding site individually but can also be bivalently bound to both sites (1,22,23); it is interesting to note that when thrombin is bivalently bound, one molecule is bound to fibrin binding sites found on adjacent fibrin monomers (23). This can occur because of the half-staggered nature of the fibrin protofibrils (see Fig. 1 A). After the enzymatic cleavage of fibrinogen monomers into fibrin monomers, they begin to polymerize. First, protofibrils form that are two monomer-thick chains of fibrin monomers, then the protofibrils aggregate laterally (see Fig. 1 A), and finally, they form thicker fibers of bundled protofibrils (see Fig. 1 B; (18,24)).

Figure 1.

Fibrin structure and thrombin binding diagram. (A) A diagram shows the half-staggered formation of a fibrin protofibril and the possible binding interactions between thrombin and fibrin. Fibrin monomers form half-staggered chains, protofibrils. Thrombin binds via exosite 1 to the E domain, via exosite 2 to γ′ chains, and bivalently via both exosites to both the E domain and γ′ binding sites, which are localized because of the half-staggered protofibril structure. Protofibrils then aggregate laterally into bundled fibers. (B) A diagram of the cross section of a fibrin fiber is shown. Thrombin becomes trapped in the more dense core of the fiber but can diffuse freely and bind on the less dense periphery of the fiber. The binding sites associated with the dense core are inaccessible to thrombin binding. (C) Shown is a diagram of the distance between protofibrils in a fibrin fiber; the dark purple circles represent a cross section of a protofibril, and the black dotted circle represents space around each protofibril within a fiber, where de is the edge-to-edge distance between protofibrils. (D) A diagram shows the radius of a protofibril, rp, and the radius of the cylinder of space around each protofibril, rs. (E) Shown is a diagram of how the percentage of accessible binding sites is determined. The shaded light purple ring, A2, consists of approximately two protofibrils and represents the region with available, accessible binding sites. The shaded light gray circle, A1, is the region with no accessible binding sites. To see this figure in color, go online.

There are a series of previously-published experiments that investigated the bivalent binding of thrombin in which radiolabeled thrombin was bound to fibrin clots, and its dissociation was monitored in time with radioactivity. Fredenburgh and colleagues developed this experimental setup to study bivalent binding, allostery, and anticoagulants (1,5,20). In the study focused on bivalency, they demonstrated that radiolabeled thrombin bound to a preformed fibrin clot remained stably bound for upwards of 24 h (1). Additionally, they reported that γA/γ′ provided thrombin with five times greater protection than the inhibitors heparin-mediated antithrombin and heparin cofactor II.

The experimental setup designed by Fredenburgh and colleagues is ideal for mathematical modeling because the thrombin-fibrin binding is isolated by type of fibrin(ogen) and is without the added complexity of flow. Briefly, the setup is as follows. In three separate experiments, 3 μM of three distinct types of fibrin(ogen), fractionated γA/γA, fractionated γA/γ′, and wild-type, were incubated with 100 nM thrombin and 16 nM active site-blocked, radiolabeled thrombin, to form a fibrin clot around small loops of wire in centrifuge tubes. Once the fibrin clots were formed, they were removed from the centrifuge tubes and submerged in larger tubes of buffer where the thrombin could dissociate and diffuse out of the clots into the buffer solution. The fraction of thrombin remaining in the clot was monitored by removing the clot periodically over 24 h and measuring the radioactivity. A control experiment was performed for each of the three cases wherein 2 M NaCl was initially included with the thrombin to block all specific binding activity. In all the control experiments, the radioactivity (remaining thrombin) curves were nearly identical, with almost no thrombin remaining after 12 h. The types of fibrin(ogen) used in the experiments consisted of two fractionated types and wild-type. Fractionated γA/γA fibrin had no γ′ chains, so all thrombin binding in this situation occurs solely between the fibrin E domain and thrombin exosite 1; fractionated γA/γ′ fibrin(ogen) had a γ′ chain on every monomer, and wild-type fibrin(ogen) monomers have two γ chains with 15% of them being γ′ chains, so there is binding between thrombin and fibrin E domains as well as γ′ chain. The experimental results showed that, after 24 h, the fractionated γA/γA fibrin retained nearly 20% of all thrombin, the wild-type fibrin retained around 60% of its thrombin, and the fractionated γA/γ′ case retained around 80% of its thrombin (1; Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Modeling the high-affinity binding experiments: posterior distributions of key parameters and resulting model output for the OSB scheme. Shown are the estimated posterior distribution (inset) for the high-affinity Kd, the resulting model output (solid line) with 95% credibility intervals (shaded region), and the data (dotted line) for the wild-type thrombin and fractionated γA/γ′ fibrin. Experimental data points were extracted numerically from the study by Fredenburgh et al. as described in Materials and Methods (1).

Another study from the same group focused on the allosteric nature of thrombin using a similar experimental setup but included exosite 1- and exosite 2-directed ligands, HD1 and HD22 (20). The major difference in the experimental procedures between these two studies were that each clot was formed with 10 μM of fractionated γA/γA fibrin(ogen) only and 15 nM FXIII, and then, each clot was submerged in buffer or buffer plus 20 μM HD22, 5 μM HD1, or 2 M NaCl, which was the control. The authors reported that whereas HD1 fully disrupted the binding to γA/γA fibrin via exosite 1, which was intuitive, the HD22 partially disrupted the thrombin binding because of allostery between the two exosites—this had to be due to HD22 interaction with exosite 2, which is not directly involved with γA/γA fibrin-thrombin binding.

Fibrin-thrombin binding has been previously described as low- and high-affinity binding interactions (25), in which the low-affinity binding is associated with the fibrin E domain sites and thrombin exosite 1 interactions, and the high-affinity binding is associated with γ′ fibrin and thrombin exosite 2 interactions (14). Here, both the low- and high-affinity binding could be described as “one-step” binding (OSB); for example, even though high-affinity binding has been shown to be bivalent where thrombin binds to fibrin via both exosites (1,22), it is essentially assumed to become bivalently bound, through both exosites, at the same time and in one single step. It is interesting to note, however, that the dissociation constants for low-affinity exosite 1 to E domain binding have been reported between 1.5 and 4.9 μM and for exosite 2 to γ′ binding have been reported to be ∼9 μM, which is not “high” affinity in comparison to the aforementioned low-affinity constants. Under the high- and low-affinity, OSB assumption, a dissociation constant for the high-affinity binding, was reported to be between 0.01 and 0.29 μM (1, 14, 22, 29), with the majority of the values near 0.1 μM. Mathematical models based on OSB schemes with dissociation constants near 0.1 μM have not been able to explain experimental data showing thrombin bound to fibrin for long periods of time (2,3).

Bivalent binding is unlikely to occur in a single step and is much more likely to occur in multiple, sequential steps, which we will denote as sequential-step binding (SSB); to our knowledge, this notion of sequential binding steps has been absent from the mathematical models and kinetic descriptions of the thrombin-fibrin binding process (2,3). There is a clear discrepancy that had arisen in the literature in regards to the measured rate constants, the kinetic schemes, and what models can explain the experimental data. Thus, the objective of this study was to determine if an OSB scheme with modified dissociation constants or an SSB scheme is able to describe experimental thrombin-fibrin binding data. In particular, we wanted to explain the dissociation data from Fredenburgh and colleagues, previously described (1). Thus, we considered both an OSB and SSB scheme for thrombin-fibrin binding and translated these schemes into appropriate mathematical models that described the binding dynamics and diffusive motion of thrombin within fibrin clots. The novel aspect of our SSB model is how we incorporate the adjacent fibrin monomer binding into the kinetic scheme, which allows us to account for the physical proximity of the available binding sites. We used Bayesian inference to estimate distributions for model parameters that best fit the previously published experimental data. We found that the OSB and SSB models can both accurately describe the experimental data. With the OSB model, we found that our estimated dissociation constant had to be much smaller than what has been previously reported in the literature. However, for either model to accurately describe the data, we had to make an additional assumption that some thrombin was, somehow, irreversibly sequestered by the clot. We hypothesized that thrombin used to cleave the fibrinogen and polymerize the fibrin could become physically trapped within the fibrin fibers during the polymerization phase. Using Bayesian inference with our model, we estimated that roughly 30% of the thrombin becomes trapped inside fibrin fibers during polymerization for the prescribed concentrations of thrombin and fibrin(ogen), in the experiments without FXIII (1). Although both models were able to reasonably explain the experimental data, we found strong statistical support for the SSB scheme using model selection. Finally, because only the SSB model was able to account for and distinguish both thrombin exosites, we applied it to the situation with exosite-directed ligands and found that it could accurately describe the experimental data.

Materials and Methods

OSB and SSB to describe thrombin-fibrin interactions

We consider two scenarios that each contain the same description for low-affinity thrombin-fibrin binding but differ in their kinetic schemes that describe the high-affinity, thrombin-fibrin binding interactions: the OSB scheme and the SSB scheme. In both scenarios, free thrombin (T) binds to low-affinity binding sites (L) within the E domain and transitions to the low-affinity bound state (BL); these events are assumed to occur via exosite 1 on thrombin. The OSB scheme also includes direct binding between free thrombin (T) and high-affinity binding sites (H). The OSB schemes work under a simplified assumption whereby thrombin binds to the γ′ chain on fibrin, via both exosite 1 and 2, but in one binding reaction step; thrombin in this reaction transitions to the high-affinity bound state (BH). The kinetic schemes and associated constants are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

OSB Reactions and Kinetic Constants

The SSB scheme describes combinations of possible binding interactions between free thrombin (T), low-affinity binding sites on the E domain, and the γ′ chains of fibrin. When a thrombin molecule is bivalently bound to fibrin, it is actually straddled between two distinct fibrin monomers, to the E domain on one monomer via exosite 1 and to the γ′ chain on the other monomer via exosite 2; this is possible because of the half-staggered nature of protofibrils within the fibrin fibers (see Fig. 1). However, only a fraction of the fibrin monomers contain a γ′ chain, and thus, the model must be able to distinguish between low-affinity binding sites on E domains that are in proximity to γ′ chains and those that are not. Consider L to be the low-affinity binding sites on the E domain that are not in proximity to a γ′ chain and L′ to be the sites that are in proximity to a γ′ chain. Let G represent γ′ binding sites, and BL, BL′, and BG represent the corresponding bound states of thrombin. Thrombin bivalently bound to both an E domain site and a γ′ site is represented by B. The kinetic schemes and associated constants are listed in Table 2.

Table 2.

SSB Reactions and Kinetic Constants

Note that the kinetic constants for the sequential steps are unique in that and are dimensionless because kon,G2, koff,G, kon,L2, and koff,L all have units of inverse time.

The populations of each species described in the kinetic schemes can be tracked by transforming the schemes into systems of differential equations using the law of mass action. For example, the ordinary differential equation that tracks BL′ is as follows:

| (1) |

The first two terms represent free thrombin binding and unbinding from the low-affinity, E domain binding sites; the second two terms represent the sequential binding event in which thrombin bound to the low-affinity binding site via exosite 1 transitions to being bivalently bound by binding to the γ′ chain via exosite 2.

Reaction-diffusion model

We model the experiments carried out by Fredenburgh and colleagues (1) by considering thrombin that diffuses and reacts with various binding sites within a spherical fibrin clot. We assume that the clots are radially and axially symmetric so that the three-dimensional reaction-diffusion partial differential equations that describe this process will simplify to one dimension. The independent variables, time and space, are denoted t and r with r = 0 being the center of the spherical clot and r = R being the outer edge. To enforce symmetry at the center, we apply a reflective boundary condition at r = 0. In the experiments, the clot filled with bound thrombin is submerged in a large bath of buffer in which there is no thrombin, and so we assume an absorbing boundary condition at r = R. The reaction-diffusion equation and corresponding boundary conditions for thrombin in the SSB scenario are as follows:

| (2) |

| (3) |

| (4) |

where D is the diffusion coefficient, and R(T, L, L′, G, BL, BL′, and BG) represents the reactions defined for the SSB scenario. Note that a similar equation exists for the OSB scenario and only differs by reaction terms. For all bound, immobile species, we have that D = 0 because they are fixed within the structure of the clot—only free thrombin can diffuse out of the clot. Full model equations for both the SSB and OSB scheme appear in Supporting Materials and Methods, Sections S1 and S2, respectively.

Exosite-directed ligands

The SSB scheme, but not the OSB scheme, allows for modeling the dynamics of thrombin exosite-specific interactions with fibrin. Petrera and colleagues performed experiments to study the allosteric behavior of thrombin; they performed similar thrombin dissociation experiments but with additional ligands that bound specifically to exosite 1 (ligand HD1) and to exosite 2 (ligand HD22) (20). The ligands were introduced into the system in the buffer in which the clot with bound thrombin was submerged. Thus, the ligands in this experiment could diffuse into the clot from the buffer after the thrombin-fibrin system had come to equilibrium.

To investigate specific binding motifs, we devised a model of these experiments to see how it would perform. Here, we denote HD22 as the HD22 ligand, T22 as thrombin bound to HD22 via exosite 2, and C as a short-lived intermediary complex of thrombin bound to the ligand via exosite 2 and also to the low-affinity E domain sites (L) on fibrin via exosite 1. Similarly, HD1 and T1 represent the ligand HD1, specific to exosite 1, and thrombin bound to HD1, respectively.

To adapt our SSB reaction-diffusion model to model these experiments and include these new ligands, we included the differential equations that arise from transforming the kinetic schemes in Table 3 and adjusted the outer-edge boundary conditions to be set to the corresponding concentration in the buffer solution.

Table 3.

Reactions Included in the Model of Exosite-Directed Ligand Experiments

Numerical simulations

We simulated the experiments by Fredenburgh and colleagues (1) using two algorithms, one with and one without the assumption that a fraction of thrombin becomes physically trapped within the fibrin fibers. The simulations with these two assumptions were carried out as follows:

Without trapped thrombin

-

1)

Equilibration phase is as follows. All available thrombin and fibrinogen are incubated as the fibrin fibers form. Model equations are evolved forward in time until they reach an equilibrium, using values for initial concentrations of thrombin and fibrin reported in the experiments. During this phase, thrombin is not allowed to diffuse out of the clot, so in this step, we set the outer-edge boundary condition to be reflective.

-

2)

Dynamic simulation of thrombin dissociation is as follows. The outer-edge boundary conditions are switched to absorbing, the initial conditions are set to those computed in the equilibration phase, and the model equations for all species are evolved forward in time.

-

3)

Calculate the fraction of thrombin remaining in the clot. Concentrations of all thrombin species in the spherical clot are summed, normalized by the initial thrombin, and reported.

With trapped thrombin

-

1)

Equilibration phase I is as follows. All available thrombin and fibrinogen are incubated as the fibrin fibers form. Model equations are evolved forward in time until they reach an equilibrium, using values for initial concentrations of thrombin and fibrin reported in the experiments. During this phase, thrombin is not allowed to diffuse out of the clot, so in this step, we set the outer-edge boundary condition to be reflective.

-

2)

Adjust for the fraction of trapped thrombin. If X% of thrombin is assumed to be trapped within the fibrin fibers, then X% of the bound thrombin computed in the initial equilibration phase is calculated and subtracted from the total amount of thrombin.

-

3)

Equilibration phase II is as follows. The total amount of fibrin is reduced proportionally to the percentage of accessible binding sites. The total free thrombin is reduced to the amount adjusted in the previous step. Model equations are evolved forward in time until they reach an equilibrium; boundary conditions are still assumed reflective.

-

4)

Dynamic simulation of thrombin dissociation is as follows. The outer-edge boundary conditions are switched to absorbing, the initial conditions are set to those computed in the second equilibration phase, and the model equations for all species are evolved forward in time.

-

5)

Calculate the fraction of thrombin remaining in the clot. Concentrations of all thrombin species in the spherical clot are summed with the trapped thrombin computed in step two; this total amount is normalized by the initial thrombin and reported.

The evolution of all model equations was performed numerically using the MATLAB (The MathWorks, Natick, MA) internal partial differential equation (PDE) solver, PDEPE.

Parameter estimation and model selection

Our general strategy in this study was to estimate the least number of parameters possible per set of experimental data. The experiments performed by Fredenburgh and colleagues (1) served as our main resource for model validation and parameter estimation. Their experiments were performed in such a way that we were able to independently estimate the diffusion coefficient for thrombin and the kinetic rate constants for thrombin binding to various types of fibrin. The first set of experiments, which we call the “control” experiments, was designed to determine if thrombin was binding nonspecifically to fibrin in the clot; specific binding to fibrin was blocked so that thrombin would only diffuse through the clot. The authors concluded there was negligible nonspecific binding from the data, and it is with these data that we estimated the diffusion coefficient. The second set of experiments they performed were with γA/γA fibrin, which means that the only specific binding that occurred was the low-affinity binding between exosite 1 of thrombin and the E domain binding sites of fibrin. Thus, using the estimated diffusion coefficient from the previous experiments, the dissociation constant, Kd,L was estimated from these data. The final two experiments include γA/γ′ fibrin (i.e., both low- and high-affinity binding was occurring), and using the previously estimated diffusion coefficient and Kd,L, we used these data to estimate the high-affinity Kd,H (OSB) and the corresponding sequential binding rates (SSB). To extract the experimental data points from the previously published studies, we used the online data extraction tool, WebPlotDigitizer (https://automeris.io/WebPlotDigitizer/). This process involved visually marking the axes and all data points in both the figure and extraction tool and then computing the numerical values for where those data points lie.

We used a Bayesian inference approach whereby we treat model parameters as random variables with associated distributions; we construct these distributions, rather than point values, using Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) methods (26). The foundation of this methodology is Bayes theorem as follows:

where q is a vector of parameter realizations, and v is a vector of observed data. The theorem essentially states that the probability of the parameters given a set of data , the posterior distribution) is proportional to the probability of the data given a set of parameters (, which quantifies the likelihood) times the probability of the parameters themselves (, the prior distribution) (26,27). We assume that the error in the experimental data is normally distributed and use this assumption to estimate the likelihood, which is an approximation of how likely the model output is, given that the data is normally distributed about an experimentally determined mean. If there is known information about the parameters (e.g., a range of experimentally measured values), this information could be incorporated into the prior distribution. If there is no such information, it is suggested to use noninformative, or uniform, distributions for the priors (26). We assumed normal distributions for prior distributions of most estimated parameters, with the means computed with an ordinary least-squares (OLS) estimator. We assumed uniform priors for several parameters that were completely unknown. For model output and experimental data , the goal is to minimize the least-squares error, LSE, which is the Euclidean distance between each data point and its corresponding model output:

We used the MCMC technique with the Metropolis algorithm (26,28) to construct the posterior distributions of all parameters that we estimated. We used a log likelihood formulation, L, as follows:

which is the sum of the probability of each data point, given a particular set of data. Using a log likelihood lets us turn what would otherwise be a product over the individual probabilities into a sum. Under the assumption of normally distributed data, the likelihood becomes as follows:

The next step is to maximize the sum of the likelihood and the probability of a given set of parameters.

This methodology was employed to estimate distributions for koff,L, koff,H, and koff,G; in each case, we fixed the associations rates kon,L, kon,H, and kon,G to be 1/μM s and report the distributions for Kd,L, Kd,H, and Kd,G. For the sequential kinetic constants, and , we estimate each with a joint probability distribution of the corresponding on and off rates, kon,G2 and koff,G2 and kon,L2 and koff,L2, respectively. The steps for each parameter estimation can be generalized as follows: randomly sample parameter space to choose a set of parameters, simulate the mathematical model with that set of parameters, compute the log likelihood of the model output and compare it to the log likelihood of the previous model output, choose to accept or reject based on this difference, iterate, and repeat; the posterior distribution is then constructed from the accepted values in the chain. The Markov part of MCMC is an assumption of statistical independence between chain values. Because of this assumption, a single long chain is equivalent to several smaller chains that sum to the same length. Because the MCMC process involves hundreds of thousands of evaluations of the mathematical model with proposed parameters, we leverage the independence by performing many batches of MCMC runs of 20,000 iterations each, simultaneously. Upon inspection of the chains, we assumed the first 5000 iterations to comprise the “burn in” period and thus neglected these values; once the chains settle into their distribution, we then merge the multiple shorter chains to form one larger posterior distribution.

To evaluate which kinetic scheme and resulting model output provides a better overall description of the data, we use two model selection metrics: the Akaike Information Criteria (AICc, which is AIC corrected for small sample size) and the Bayesian Information Criteria (BIC) (26). If is the maximized log likelihood, then the AICc and BIC are as follows:

where k is the number of parameters estimated using MCMC, and n is the number of data used. This metric can be used to compare two models where the 2k and log(n)k penalize for additional parameters, and the rewards for being a good fit. The model that produces the smallest information criterion value is considered the superior model.

Results

Below, we describe the numerical results for validating our mathematical models with the thrombin dissociation experiments performed by Fredenburgh and colleagues (1). We used our diffusion-reaction model to simulate various experiments to independently estimate the diffusion coefficient, D, dissociation constant for low-affinity binding, Kd,L, and the kinetic rates associated with high-affinity binding for the OSB and SSB schemes, Kd,H, kon,G2, and kon,L2. In all cases, we employed a Bayesian approach to infer a distribution for uncertain parameters with associated prior distributions; upon propagation of each prior distribution through the mathematical model and using the likelihood of the experimental data, we learned the posterior distributions for the parameters. Additionally, we describe model results from simulating experiments with exosite-directed ligands using the SSB model. Because the binding dynamics depend on the structure of the clot itself (29), we begin with estimations of some physical characteristics of the fibrin fibers within the experimental system we are modeling.

Estimated physical characteristics of fibrin fibers

When fibrin polymerizes, it first forms half-staggered chains of fibrin monomers called protofibrils, which then aggregate laterally to form fibers that then comprise the fibrin mesh of a clot (24,30). The quality, thickness, and density of fibers varies as the amounts of fibrinogen and thrombin change (18,29). In the experiments performed by Fredenburgh and colleagues, ∼3 μM fibrinogen was polymerized into fibrin with 100 nM thrombin; these conditions yield thin fibrin fibers that are ∼100 nm in diameter (29), in line with approximations from other studies, suggesting thin fiber diameters to be ∼97.5 nm (31).

Distance between protofibrils within a single fiber

Here, we provide two separate calculations to get an estimate of the mean distance between protofibrils within a fibrin fiber. First, we consider a single cylindrical fibrin fiber with radius 48.75 nm (31,32), in which the fibrin concentration within the fiber is μM (32,33). Next, we examine a small cylindrical slice of a fibrin fiber with cross-sectional area A = π48.752 nm2 and length, l, of 45 nm, the length of a single monomer of fibrin (18,34,35). The estimate of the number of protofibrils (two monomers thick) and their edge-to-edge distance in the slice can be estimated as follows:

For simplicity, we will assume that the fibrin fiber is ∼83 protofibrils thick and then estimate their edge-to-edge distance. To do this, we used a circle-packing algorithm that placed 83 cylinders into the fiber slice and output the radius of each cylinder (http://web.archive.org/web/20080207010024/http://www.80multimedia.com/winnt/kernel.htm). We determined that each smaller cylinder has a radius of rs ≈ 4.65 nm; these cylinders are considered to be occupied by a single protofibril plus additional edge-to-edge space between protofibrils (see Fig. 1, C and D). If we assume that a protofibril radius, rp, ranges between 2.5 and 5 nm (36), then the estimated range of edge-to-edge distance is de = 2(rs − rp) = 0.0 − 4.3 nm (see Fig. 1 D).

Other estimates of fibrin fiber diameters exist in the literature, and we have used these values to estimate the edge-to-edge distance for comparison with the one above. For example, Ferri et al. reported a single fibrin fiber to have a radius of 45.5 nm and a mass-to-length ratio of 1.68 × 106 Da/nm (37). Assuming that a single monomer has an effective length of ∼45 nm (18,34,35), then the estimate of the number of monomers in a cylindrical slice of length 45 nm is as follows:

If each cylindrical fiber with cross-sectional area A = π45.52 nm2 is roughly divided into 111 smaller cylinders of equal volume, we utilize a circle-packing algorithm (http://web.archive.org/web/20080207010024/http://www.80multimedia.com/winnt/kernel.htm) to determine that each smaller cylinder has a radius of rs = ∼3.75 nm. These cylinders are considered to be occupied by a single protofibril plus additional edge-to-edge space between protofibrils (see Fig. 1 C). If we assume that a protofibril radius, rp, ranges between 2.5 and 5 nm (36), then the estimated possible range of edge-to-edge distance is de = 2(rs − rp) = 0 − 2.5 nm (see Fig. 1 D).

These estimates of edge-to-edge distances between protofibrils in a fibrin fiber are either on the same order or less than the effective size of a thrombin molecule, which is 4.5 × 4.5 × 5 nm3 (35).

Inaccessible binding sites within fibrin fibers

Given the estimates above for the spacing between protofibrils, it is unlikely that a thrombin molecule would be able to diffuse into or out of an already formed fibrin fiber. However, it was recently shown that fibrin fibers are less dense at the outer edges than in the core, so that the protofibrils are arranged in a spoke-like manner (36) and that only the peripheral layers of fibrin fibers dynamically remodel (38). Taken together with our small edge-to-edge distance estimates, this suggests that only the outer most protofibrils are accessible to thrombin on the exterior of the formed fibrin fibers. To estimate the percentage of total binding sites that are physically inaccessible to thrombin, we assume the following: 1) protofibrils are arranged in circular layers within the fiber (see Fig. 1), 2) only the two outer most layers of protofibrils are accessible for binding, and 3) the protofibrils have edge-to-edge distances estimated above. Next, we consider a ring on the outer edge of a fibrin fiber that is two protofibrils thick (purple shaded region in Fig. 1 E) to define the region where protofibrils have accessible binding sites. Conversely, the gray shaded region in Fig. 1 E is representative of protofibrils with inaccessible binding sites. Assuming that the outside ring has a width of 4 × rs (Fig. 1 E), we take the ratio of the areas, to be the percentage of total binding sites within a fibrin fiber that are likely to be inaccessible to thrombin. With our two estimates of rs, we found that between 38 and 44% of the binding sites are inaccessible. In the relevant simulations below, we assume that 41% of all fibrin binding sites (average of the two estimates above) are inaccessible to free thrombin. This translates to a reduction of the initial condition for fibrin in the model.

Estimating the diffusion coefficient for thrombin

The goal was to estimate the diffusion coefficient for thrombin by utilizing data from the control experiment in which thrombin diffuses through and out of the clot into buffer but does not bind fibrin with any specific interactions. To achieve this, we used a diffusion equation in spherical coordinates to model thrombin moving through a spherical clot. With this setup, the only parameter that was uncertain was the diffusion coefficient for thrombin (see Supporting Materials and Methods, Section S3 for a description of why we estimate only the diffusion coefficient here).

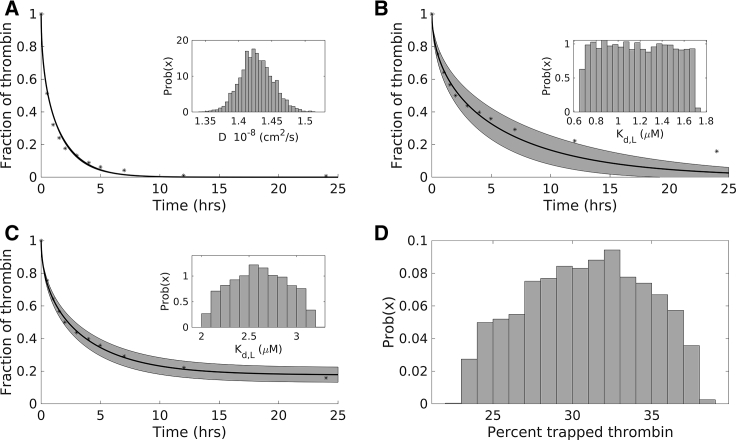

As described in the Materials and Methods, we simulated the thrombin dissociation experiments and reported the total amount of thrombin remaining in the clot, normalized by the initial amount of thrombin. We assumed a normal prior distribution with a mean and SD of 5 × 10−7 and 2.5 × 10−8 cm2/s, respectively. Fig. 2 A shows the experimental data (black circles) and the model output distribution of the thrombin remaining in the clot as a function of time; we plot the mean (solid line) along with a 95% credibility interval, represented by the gray shaded region. The thrombin output distribution appears to be only a single curve because the posterior parameter distribution was very tight around the mean (see Fig. 2 A, inset for histogram of posterior distribution).

Figure 2.

Modeling diffusion and low-affinity binding experiments: posterior distributions of key parameters and resulting model output. (A) Shown are the estimated posterior distribution (inset) for the diffusion coefficient, the resulting model output (solid line) with 95% credibility intervals (shaded region), and the data (dotted line) for the control experiments. (B) Shown are the estimated posterior distribution for the dissociation constant for low-affinity binding (inset) in the absence of physically trapped thrombin, the resulting model output (solid line) with 95% credibility intervals (shaded region), and the data used to estimate the Kd (dotted line). (C) Shown are the estimated posterior distribution for the dissociation constant for low-affinity binding (solid line) under the assumption of physically trapped thrombin, the resulting model output (solid line) with 95% credibility intervals (shaded region), and the data used to estimate the Kd and trapped thrombin percentage. (D) Shown is the posterior distribution of the percentage of thrombin that is physically trapped within the fibrin fibers. Experimental data points were extracted numerically from the article by Fredenburgh et al. as described in Materials and Methods (1).

The data can be described with an approximately normal posterior distribution for the diffusion coefficient with a mean of 1.4268 × 10−8 cm2/s (see Fig. 2 A, inset). Because of the tight distribution around the mean, the diffusion coefficient will be fixed to a point value set to the mean of this distribution for all future simulations in this study. Based on the value of the estimated diffusion coefficient, which is within a reasonable range for a small particle diffusing in water, this is in line with the experimental findings that that there was little to no nonspecific binding.

Estimating the low-affinity dissociation constant I

The experimental data using γA/γA fibrin was used to estimate the low-affinity binding constant, Kd,L. To model these experiments, we used coupled reaction-diffusion equations that described the diffusion of thrombin (with diffusion coefficient fixed to the estimated mean in the previous section), the reaction for low-affinity binding between exosite 1 of thrombin, and the E domain sites on fibrin (reaction 1, Tables 1 and 2), with the assumption that 41% of the fibrin binding sites were inaccessible to thrombin. We fixed the kon,L to be 1/μM s and used Bayesian inference to estimate koff,L; we report a posterior distribution for Kd,L = koff,L/kon,L. We assumed a normal prior distribution for koff,L, with mean 1.7 μM, estimated from OLS. Fig. 2 B shows the experimental data (black circles) and the model output distribution of the thrombin remaining in the clot as a function of time; we plot the mean (solid line) along with a 95% credibility interval, represented by the gray shaded region. The inset of Fig. 2 B shows the histogram of the posterior distribution for Kd,L. The constant, Kd,L, was estimated to be approximately uniformly distributed between 0.6680 and 1.7062 μM with a mean of 1.1791 μM, which seems to be within the range of experimental measurements (1, 14, 22, 29). We can see that the variation in this constant resulted in a much wider credibility interval than in the case of estimating the diffusion coefficient. Only the early time points of the experimental data (less than 10 min) are described well with this model and estimated parameter distribution; the last two data points are not falling within the credibility intervals. This model results in thrombin leaving the clot faster than it does in the experiments, and thus, we concluded that this model does not quantitatively or qualitatively represent the experimental results.

Our first attempt at modeling the γA/γA experiments failed as the resulting thrombin was leaving the clot too soon, even with an independently estimated diffusion coefficient and optimizing for the best fit kinetic rate constants. The reaction-diffusion model will eventually lead to all thrombin leaving the system, whereas the experimental data seem to show thrombin remaining at a nonzero level for extended periods of time—what is holding the thrombin inside the clot? We considered the following possibility: what if the fibrin fibers are somehow physically trapping the thrombin from leaving the clot?

Physical trapping of thrombin

We previously estimated that the average distance between protofibrils was small enough to prevent thrombin from diffusing into the fibers and then estimated the fraction of binding sites that would be inaccessible because of this physical barrier. This seems reasonable when considering fully formed fibrin fibers. However, in the experiments performed by Fredenburgh and colleagues (1), the measured thrombin remaining in the clots includes the thrombin that was used to form the clots and is thus present during formation of fibers. Additionally, other researchers previously suggested that thrombin molecules become trapped within bundles of fibrin fibers during polymerization (29). Expanding on this idea, we hypothesize that thrombin becomes trapped within individual fibers while they are forming, and because the thrombin is radiolabeled, the radioactivity is still measurable, even though the thrombin molecules are trapped within the fiber.

Estimating the low-affinity dissociation constant II

The fraction of total thrombin that becomes physically trapped within fibers is difficult to estimate, and thus, we assumed this fraction to be an uncertain parameter, incorporated in the model as described in the model algorithm section of the Materials and Methods. The trapped fraction parameter was estimated simultaneously with Kd,L. We assumed the trapped fraction had a normal prior distribution with a mean and SD of 20 and 1, respectively. Fig. 2 C shows the experimental data (black circles) and the model output distribution of the thrombin remaining in the clot as a function of time; we plot the mean (solid line) along with a 95% credibility interval, represented by the gray shaded region. The inset of Fig. 2 C shows the histogram of posterior distribution for Kd,L, considering that a fraction of thrombin can be physically trapped. The constant, Kd,L, was estimated to be approximately normally distributed between with a mean of 2.6 μM and SD 0.84 μM, which encompasses the range of experimental measurements (1,14,22). Fig. 2 D shows the histogram of the posterior distribution for the trapped thrombin fraction, which was estimated to be approximately normally distributed with a mean of 31% and SD 14%. Fig. 2 C clearly shows good qualitative and quantitative agreement of the model output and the experimental data; all data points lie within the 95% credibility intervals, and the remaining fraction of thrombin no longer tends to zero. These results are in much better agreement than those considered without trapped thrombin. To quantify this, we computed a model selection test with the AICc (see Materials and Methods for description) and found it to be 922 for the case without trapped thrombin and −3.55 with trapped thrombin. The difference between the criteria for each model gives evidence for statistical support, not the absolute numerical value, in which the model with the lower value is preferred. Observing a difference greater than 10 indicates a very strong statistical preference for the model with the lower value (39). The differences between the models were computed as AICcNoTrappedThrombin − AICcWithTrappedThrombin = 925.55. Thus, we find strong statistical support for the model with the trapped thrombin assumption over the model without it.

Two potential kinetic schemes to explain thrombin dissociation experiments

We have estimated all parameters describing the physical characteristics of fibrin fibers, the diffusion coefficient of thrombin, the trapped thrombin percentage, and the low-affinity dissociation constant, Kd,L. These estimates encompass the control and fractionated γA/γA experiments. We now will continue to use Bayesian inference along with the two remaining sets of data from the wild-type and fractionated γA/γ′ experiments to estimate the rates associated with high-affinity binding. For the OSB-derived model, we estimate Kd,H, and for the SSB-derived model, we estimate kon,L2 and kon,G2. The estimation of the posterior distributions was slightly different than the previously described ones because, here, we sampled from distributions for the previously estimated parameters; for each instance of the MCMC chains, we took 50 independent samples from the previously estimated parameter distributions and computed 50 time courses for the remaining thrombin, and then the mean of these 50 time courses was computed and used in the likelihood calculation.

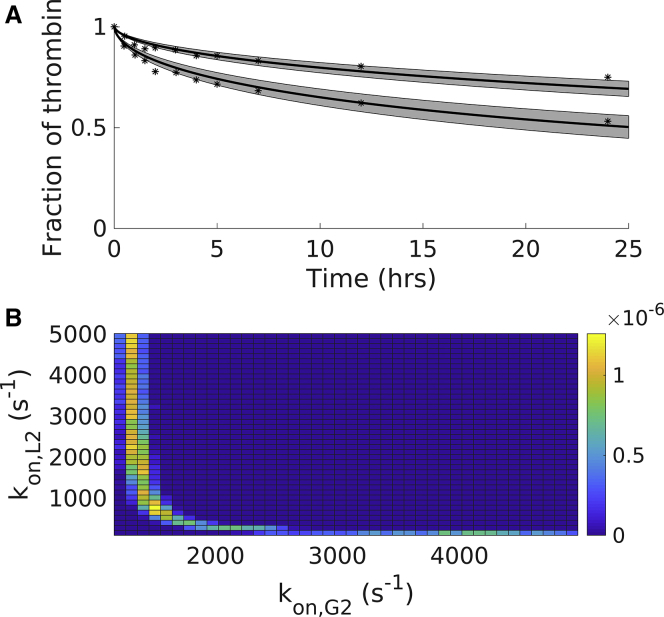

OSB model

To model these experiments, we use a reaction-diffusion equation with the reactions described in Table 1. We assumed the diffusion coefficient, the parameters for low-affinity binding, and the percentage of trapped thrombin were known (estimated above) and used the experimental data and Bayesian inference to learn the parameters for the high-affinity binding reaction. More specifically, we fixed the kon,H to be 1/μM s and estimated koff,H; we report a posterior distribution for Kd,H = koff,H/kon,H. We assumed a normal prior distribution for koff,H, with mean 0.01 s−1 and SD 0.0005 s−1, estimated from OLS. Fig. 3 shows the experimental data (black circles) and the model output distribution of the thrombin remaining in the clot as a function of time; we plot the mean (solid line) along with a 95% credibility interval, represented by the gray shaded regions. We can see that all but one data point lie within the 95% credibility intervals, indicating good agreement between model and data. The inset of Fig. 3 shows the histogram of posterior distribution for Kd,H, estimated to be approximately uniformly distributed between 0.0217 and 0.0303 μM, which is in line with one of the experimental measurements (1) but not others (14,22).

SSB model

To model these experiments, we use a reaction-diffusion equation with the reactions described in Table 2. We assumed the diffusion coefficient, the parameters for low-affinity and the γ′ binding (reactions 1–3, Table 2), and the percentage of trapped thrombin were known (estimated above); we used the experimental data and Bayesian inference to learn the parameters for the high-affinity binding reactions. More specifically, because the rates for the sequential binding steps both have units of inverse time, we fixed the koff,G to be 9/s and used the previously estimated distribution for koff,L and estimated the corresponding distributions for kon,G2 and kon,L2; we report the two-dimensional joint distributions for these rates and not the dissociation constants as we have done in the previous sections. For the prior distributions for both of these rates, we assumed a uniform distribution between 0/s and 5000/s, a noninformative prior.

Fig. 4 A shows the experimental data (black circles) and the model output distribution of the thrombin remaining in the clot as a function of time; we plot the mean (solid line) along with 95% credibility intervals computed by assuming the two rates kon,G2 and kon,L2, are jointly distributed. This means that for each output, the values of kon,G2 and kon,L2 are chosen from the same instance of the MCMC chain rather than independently sampled from their own MCMC chain. We originally computed credibility intervals assuming that the parameters were independently distributed, but we found that the credibility intervals were wide, and the posterior distributions were flat with high SD; this suggested that the parameters were not independent of one another. Thus, we consider them as jointly distributed, and in Fig. 4 B, we show the two-dimensional histogram of the joint posterior distribution of the two rates, kon,G2 and kon,L2. When comparing the model output to data, we can see that most of the data points lie within the 95% credibility intervals, indicating good agreement between model and data.

Figure 4.

Modeling the high-affinity binding experiments: posterior distributions of key parameters and resulting model output for the SSB scheme. (A) Shown are the resulting model output (solid line) with 95% credibility intervals (shaded region) and the data (dotted line) for the wild-type thrombin and fractionated γA/γ′ fibrin. (B) Shown is the estimated joint posterior distribution for sequential rates from the SSB scheme. Experimental data points were extracted numerically from the article by Fredenburgh et al. as described in Materials and Methods (1). To see this figure in color, go online.

Model selection test

Both the OSB and SSB models were in good qualitative and quantitative agreement with the experimental data, but the SSB had an additional parameter. We wanted a way to choose among different models, with statistical support, allowing for the penalization of the likelihood of the data because the complexity of the model. We calculated the corrected Akaike Information Criterion (AICc) and the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) for the remaining thrombin, output from both the OSB and SSB model, evaluated at the mean of the posterior distributions. Both metrics penalize the likelihood of the data with the complexity of the model, which results in the SSB model and its extra parameter having a greater penalty. The difference between the criteria for each model gives evidence for statistical support, not the absolute numerical value, where the model with the lower value is preferred. Observing a difference greater than 10 indicates very strong statistical preference for the model with the lower value (39). The differences between the models were computed as AICcOSB − AICcSSB = 23 and BICOSB − BICSSB = 22. Thus, by either metric, we find statistical support for neglecting the OSB model in favor of the SSB model.

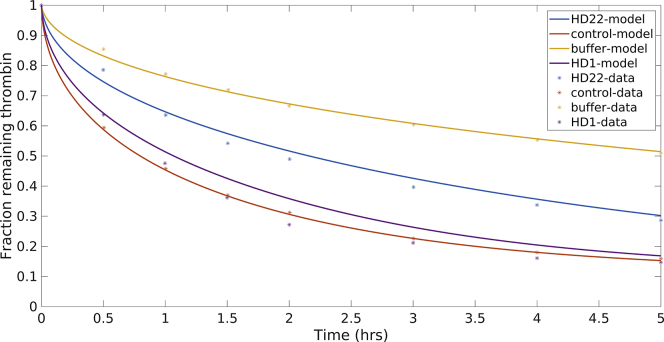

Exosite-directed ligands using the SSB model

The SSB model was previously selected as the preferred model, over the OSB model, to represent data from radiolabeled thrombin dissociation experiments (20). Here, we show that, in addition to that model selection, the SSB model but not the OSB model can be utilized to explore the use of exosite-directed ligands, which are designed to exploit the allosteric behavior of thrombin. This behavior is becoming increasingly important in the development of anticoagulants that target thrombin specifically (20). The SSB model was adapted to include the binding of two exosite-directed ligands, HD1 (thrombin exosite 1) and HD22 (thrombin exosite 2), and the model was evaluated to see if it could reproduce the results of experiments performed by Petrera and colleagues (20).

We have shown above that physical characteristics of the fibrin clots (for example, the percentage of available fibrin binding sites and physically trapped thrombin) are necessary to incorporate into mathematical models. Moreover, these characteristics vary with the ratio of fibrinogen to thrombin that form the clot. Petrera and colleagues used 100 nM thrombin and 10 μM fibrinogen, which is a ratio of fibrinogen to thrombin that is three times higher than that in the experiments of Fredenburgh et al. This suggests that the fibrin fibers that form in these experiments will be larger in diameter and have less densely packed protofibrils than those formed in the previous experiments. We suspected that this would result in a decreased percentage of trapped thrombin and an increased percentage of available binding sites. Therefore, we adjusted these parameters in the SSB model to best represent the directed-ligand data. We found that 13% trapped thrombin and 75% available fibrin binding sites gave good agreement with the data. For the model simulations, we used the means of all parameter distributions estimated above for the SSB model. Fig. 5 shows the resulting model output for remaining thrombin in the clot over the course of 5 h for four different experimental setups: control case, in which thrombin only diffuses; buffer case, in which only γA/γA binding is allowed; HD1 case, in which HD1 binds thrombin exosite 1 and blocks it from binding the E domain sites on fibrin; and the HD22 case, in which HD22 binds the thrombin exosite 2 and modifies the binding of exosite 1. The addition of HD22 reduced the thrombin retention by half compared to the control case, and the addition of HD1 restored the retention to the levels of the control case. The model output was in excellent agreement in all cases.

Figure 5.

The SSB model was modified to include the exosite directed ligands, HD22 and HD1. The SSB was modified to include exosite-directed ligands, HD22 and HD1. Here, all relevant parameters are taken to be the mean of previously estimated parameters. The available number of binding sites was fixed to 75%, and the percentage of trapped thrombin was fixed to 13% to account for the potential differences in clot structure arising from initial molar ratios of fibrinogen to thrombin. Experimental data points were extracted numerically from the article by Petrera et al. as described in Materials and Methods (20). To see this figure in color, go online.

Discussion

Thrombin is known to bind fibrin clots and remain stably bound for extended periods of time. This sequestration of thrombin is often described as two distinct binding events between thrombin and fibrin, one of high affinity and one of low affinity. The existing one-step kinetic schemes and the measured dissociation constants found in the literature cannot account for the experimental data obtained from thrombin-fibrin binding experiments. There is a clear discrepancy between the existing models, kinetic parameters, and experimental data.

In this study, we wanted to determine if an OSB scheme with modified kinetic parameters or our proposed SSB scheme would describe experiments in which the dissociation of radiolabeled, fibrin-bound thrombin was monitored over 24 h. We formulated two mathematical models, both of the reaction-diffusion PDE type, one with the OSB scheme and one with the SSB scheme to represent the thrombin-fibrin binding dynamics. We found that both models could accurately describe the data but with some caveats. The SSB model does have an extra parameter that can be adjusted, but even with this added complexity, the AICc and BIC both give strong statistical support for choosing the SSB model over the OSB model when comparing model output to experimental data. Both models only showed good agreement with the experimental data under the additional assumption that a portion of thrombin became physically trapped within the fibrin fibers during polymerization.

Two binding schemes: one step and sequential step

The OSB model accurately described the data but only with dissociation constants for high-affinity binding that we estimated to be in the range 0.02–0.04 μM. Our estimate is consistent with only one (1) of four separate values found in the literature (1, 14, 22, 29) for this high-affinity dissociation constant. We note that two different experimental protocols were used across these four studies, surface plasmon resonance (1) and Scatchard analysis (40) of binding experiments (14,22,29), and that these two protocols led to two distinct ranges, differing by an order of magnitude in the estimated rates. It was noted in Banninger et al. (29) that because of the fact that some thrombin was irreversibly bound to the fibrin (i.e., physically trapped), Scatchard analysis was not appropriate to quantify the binding parameters.

After studying the literature about the bivalent nature of thrombin binding, we devised a new kinetic scheme to represent bivalent thrombin-fibrin binding. To our knowledge, this notion has not yet been incorporated into mathematical models of thrombin-fibrin binding and thus is a new way to model and probe these dynamics. However, the novel part of the scheme is not the bivalent nature of thrombin itself but the fact that our scheme can capture the proximity of binding sites on E domains to binding sites on γ′ chains; by accounting for two types of low-affinity sites on E domains, ones that are and are not in proximity to γ′ sites, our model is uniquely able to model various fractionated forms of fibrin(ogen).

Because the SSB model can explicitly represent both thrombin exosites, we extended it to study exosite-directed ligands and thrombin allostery (20). Using kinetic rates estimated in this work in combination with kinetic rates reported for the exosite-directed ligands, our model gave a good qualitative match to the experimental data, with the correct relative responses between the different ligands. This set of experimental data was based on different loading concentrations of fibrin(ogen) and had additional FXIIIa, which could change the fibrin structure (18,29) and the amount of trapped thrombin (29). Consequently, we systematically varied the percentage of available binding sites and the percentage of trapped thrombin. We were able to obtain very good qualitative fits for these exosite-directed ligand experiments. Because multiple studies have shown allosteric linkage between thrombin exosites and between the exosites and the active site (5,20,41,42), our SSB model could be used to simulate these scenarios and further probe the thrombin binding dynamics. Our model could also be used to study thrombin-specific aptamers (43), thrombin inhibitors sensitive to the enzymes of fibrinolysis enzymes (44,45), and bivalent direct thrombin inhibitors, such as hirudin and bivalirudin (46). To our knowledge, mathematical modeling tools have not yet been applied to these situations.

Trapped thrombin hypothesis

We are proposing a physical mechanism for thrombin retention within fibrin clots. Based on plausible physical structures of fibrin fibers, we estimated that an average distance between protofibrils in a fibrin fiber could be less than the effective size of a single thrombin molecule. Additionally, fibrin fibers are suggested to be arranged in a spoke-like manner with dense cores and less dense outer edges (36). Thus, we further hypothesized that if thrombin was bound to a protofibril and did not have time to dissociate and diffuse away before protofibril aggregation into fibers, the thrombin could become irreversibly, physically trapped inside the fibrin fiber. As a consequence of this, we also considered that not all fibrin binding sites within a formed fiber would be accessible to mobile thrombin on the exterior of the fiber. It has been suggested that thrombin could be trapped within bundles of fibrin fibers (29), but to our knowledge, the idea that thrombin could be irreversibly trapped within single fibers has not yet been presented in the literature.

This notion of physical trapping of thrombin may provide some insight into paradoxical observations regarding fibrinolysis, the enzymatic degradation of fibrin clots. Thrombin is known to affect the structure of fibrin clots; fine clots composed of thin, but densely packed fibers result from high concentrations of thrombin, whereas coarse clots composed of thicker, less densely packed fibers with large pores between them result from smaller thrombin concentrations (47,48). In the literature, however, one can find conflicting information regarding lysis speeds; fine clots degrade more slowly than coarse clots (49, 50, 51) or the opposite, or there is no difference (52, 53, 54), and thick fibers are individually lysed more slowly than thin fibers (55). Combined mathematical modeling and experiments by Bannish and colleagues reconciled part of this story by adding an additional metric; they showed that the number of tissue plasminogen activator molecules in the system determines what type of clot degrades faster (31,56). However, their models did not include the inhbitor TAFIa. Our hypothesis regarding trapped thrombin could provide another interpretation of lysis speeds, pointing to trapped thrombin as playing a significant role in the process. In particular, clots formed in the presence of large amounts of thrombin would yield fine clots with thin fibers that, in their dense core, have smaller average distances between protofibrils; thus, these thin fibers could potentially trap more thrombin on the inside of the fibers and lead to less availability of fibrin binding sites for thrombin to get in from the outside. The result would be a local source of thrombin within the fibers, available to cleave thrombin activatable fibrinolysis inhibitor (TAFI) into TAFIa, which would then be immediately available to inhibit plasmin, the enzyme that degrades fibrin. On the other hand, thicker fibers would trap a smaller portion of thrombin and would thus potentially have a smaller local source of TAFIa. Even though thin fibers lyse faster individually, the thrombin being released from the fiber as it is being broken down could activate more TAFI and slow the fibrinolytic front.

Thrombin-fibrin binding under flow

A few recent experimental studies have focused on clot-bound thrombin under flow. Haynes and colleagues demonstrated that thrombin allowed to bind a preformed fibrin matrix remains stably bound under flow at venous shear rates for upwards of 30 min (2). The fibrin-bound thrombin was shown to be irreversibly inhibited by antithrombin and heparin, reversibly inhibited by dabigatran, and only minimally inhibited by antithrombin alone. Because of the large size of antithrombin, the authors proposed that thrombin was inhibited by the antithrombin-heparan complex because it was constantly redistributing between different possible bound states associated with fibrin, and in doing so, it was exposed to the inhibitory complex. Muthard and colleagues showed that γ′ fibrin helped to localize and inhibit thrombin generation at venous shear rates but had little to no effect on thrombin generation at arterial and pathological shear rates (57). In a subsequent study, the same group found that during clot formation under flow, fibrin concentrations in the formed clots were much greater than plasma levels of fibrinogen and that large amounts of thrombin were nearly irreversibly sequestered by that same fibrin; the authors suggested that for this to occur, there must be a much higher affinity of thrombin for fibrin than had been previously reported in the literature (3). This suggestion is in line with the idea of an OSB scheme—that a single-step model would describe the binding but that the dissociation constant had to be on the lowest end of the reported rates; however, it is equally likely that the SSB scheme could describe these results as we have shown above. The high concentrations of fibrin and bound thrombin reported in this study imply that there were likely high concentrations of thrombin present during polymerization. Thus, our hypothesis developed under static conditions suggests that large amounts of thrombin may also become trapped within fibrin fibers under venous flow in more physiologically relevant scenarios.

Conclusions

In summary, we have demonstrated that mathematical formulations of both an OSB scheme and an SSB scheme can accurately reproduce results from thrombin disassociation experiments, with varying fibrin(ogen) types. These quantitative results hold as long as the OSB model includes dissociation constants at the lowest end of literature values and if both models are considered under the assumption that thrombin can be physically trapped within fibrin fibers as they form. If one wanted to simply model thrombin-fibrin binding with no consideration of thrombin’s bivalency, our results suggest that the OSB model with trapped thrombin and a small dissociation constant will work. However, the SSB model is the only model that can be used to study bivalent reactions. We showed that the SSB model can be used to study exosite-specific interactions that modulate thrombin binding and function. Could the trapped thrombin assumption, in part, help to explain the paradoxical speeds of fibrinolysis? This notion of trapped thrombin and TAFI interactions could be tested in the models of Bannish and colleagues, and this is a potential future direction for research. It is not yet known if thrombin can actually become physically trapped within fibrin fibers, but we hope that our results will motivate an experimental study to determine the plausibility of this idea. Other future studies include incorporating the SSB scheme into spatial models of flow-mediated coagulation and platelet aggregation (58, 59, 60) to better understand the role of thrombin sequestration by fibrin in hemostasis and thrombosis.

Author Contributions

M.K. designed and performed research, analyzed data, and wrote the manuscript. K.L. designed research, analyzed data, and wrote the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Drs. Michael Stobb, Laura M. Haynes, Suzanne Sindi, Brittany Bannish, and Keith B. Neeves for useful discussions regarding this work.

This work was, in part, supported by the Army Research Office (ARO-12369656), the National Institutes of Health (R01 HL120728), and the National Science Foundation CAREER (DMS-1848221).

Editor: James Keener.

Footnotes

Supporting Material can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpj.2019.09.003.

Supporting Material

References

- 1.Fredenburgh J.C., Stafford A.R., Weitz J.I. Bivalent binding to γA/γ′-fibrin engages both exosites of thrombin and protects it from inhibition by the antithrombin-heparin complex. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:2470–2477. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M707710200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Haynes L.M., Orfeo T., Brummel-Ziedins K.E. Probing the dynamics of clot-bound thrombin at venous shear rates. Biophys. J. 2017;112:1634–1644. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2017.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhu S., Lu Y., Diamond S.L. Dynamics of thrombin generation and flux from clots during whole human blood flow over collagen/tissue factor surfaces. J. Biol. Chem. 2016;291:23027–23035. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M116.754671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kretz C.A., Stafford A.R., Weitz J.I. HD1, a thrombin-directed aptamer, binds exosite 1 on prothrombin with high affinity and inhibits its activation by prothrombinase. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:37477–37485. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M607359200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yeh C.H., Stafford A.R., Weitz J.I. Dabigatran and argatroban diametrically modulate thrombin exosite function. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0157471. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0157471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.de Bosch N.B., Mosesson M.W., Rodriguez-Lemoin A. Inhibition of thrombin generation in plasma by fibrin formation (Antithrombin I) Thromb. Haemost. 2002;88:253–258. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kumar R., Béguin S., Hemker H.C. The influence of fibrinogen and fibrin on thrombin generation--evidence for feedback activation of the clotting system by clot bound thrombin. Thromb. Haemost. 1994;72:713–721. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weitz J.I., Hudoba M., Hirsh J. Clot-bound thrombin is protected from inhibition by heparin-antithrombin III but is susceptible to inactivation by antithrombin III-independent inhibitors. J. Clin. Invest. 1990;86:385–391. doi: 10.1172/JCI114723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Owen J., Friedman K.D., Powers E.R. Thrombolytic therapy with tissue plasminogen activator or streptokinase induces transient thrombin activity. Blood. 1988;72:616–620. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mannila M.N., Lovely R.S., Silveira A. Elevated plasma fibrinogen gamma’ concentration is associated with myocardial infarction: effects of variation in fibrinogen genes and environmental factors. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2007;5:766–773. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2007.02406.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lovely R.S., Falls L.A., Farrell D.H. Association of gammaA/gamma’ fibrinogen levels and coronary artery disease. Thromb. Haemost. 2002;88:26–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Uitte de Willige S., de Visser M.C., Bertina R.M. Genetic variation in the fibrinogen gamma gene increases the risk for deep venous thrombosis by reducing plasma fibrinogen gamma’ levels. Blood. 2005;106:4176–4183. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-05-2180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lane D.A., Philippou H., Huntington J.A. Directing thrombin. Blood. 2005;106:2605–2612. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-04-1710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Meh D.A., Siebenlist K.R., Mosesson M.W. Identification and characterization of the thrombin binding sites on fibrin. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:23121–23125. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.38.23121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Myles T., Yun T.H., Leung L.L. An extensive interaction interface between thrombin and factor V is required for factor V activation. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:25143–25149. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M011324200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Esmon C.T., Lollar P. Involvement of thrombin anion-binding exosites 1 and 2 in the activation of factor V and factor VIII. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:13882–13887. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.23.13882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ayala Y.M., Cantwell A.M., Di Cera E. Molecular mapping of thrombin-receptor interactions. Proteins. 2001;45:107–116. doi: 10.1002/prot.1130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wolberg A.S. Thrombin generation and fibrin clot structure. Blood Rev. 2007;21:131–142. doi: 10.1016/j.blre.2006.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mosesson M.W. Fibrinogen and fibrin structure and functions. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2005;3:1894–1904. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2005.01365.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Petrera N.S., Stafford A.R., Weitz J.I. Long range communication between exosites 1 and 2 modulates thrombin function. J. Biol. Chem. 2009;284:25620–25629. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.000042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lovely R.S., Moaddel M., Farrell D.H. Fibrinogen γ’ chain binds thrombin exosite II. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2003;1:124–131. doi: 10.1046/j.1538-7836.2003.00027.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pospisil C.H., Stafford A.R., Weitz J.I. Evidence that both exosites on thrombin participate in its high affinity interaction with fibrin. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:21584–21591. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M300545200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fredenburgh J.C., Stafford A.R., Weitz J.I. Modes and consequences of thrombin’s interaction with fibrin. Biophys. Chem. 2004;112:277–284. doi: 10.1016/j.bpc.2004.07.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Weisel J.W. Structure of fibrin: impact on clot stability. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2007;5(Suppl 1):116–124. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2007.02504.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu C.Y., Nossel H.L., Kaplan K.L. The binding of thrombin by fibrin. J. Biol. Chem. 1979;254:10421–10425. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Smith R.C. SIAM; Philadelphia, PA: 2013. Uncertainty Quantification: Theory, Implementation, and Applications. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kruschke J. Academic Press; San Diego, CA: 2010. Doing Bayesian Data Analysis: A Tutorial Introduction with R and BUGS. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chib S., Greenberg E. Understanding the Metropolis-Hastings algorithm. Am. Stat. 1995;49:327–335. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bänninger H., Lämmle B., Furlan M. Binding of alpha-thrombin to fibrin depends on the quality of the fibrin network. Biochem. J. 1994;298:157–163. doi: 10.1042/bj2980157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Weisel J.W. Fibrinogen and fibrin. Adv. Protein Chem. 2005;70:247–299. doi: 10.1016/S0065-3233(05)70008-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bannish B.E., Chernysh I.N., Weisel J.W. Molecular and physical mechanisms of fibrinolysis and thrombolysis from mathematical modeling and experiments. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:6914. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-06383-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Carr M.E., Jr., Hermans J. Size and density of fibrin fibers from turbidity. Macromolecules. 1978;11:46–50. doi: 10.1021/ma60061a009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Voter W.A., Lucaveche C., Erickson H.P. Concentration of protein in fibrin fibers and fibrinogen polymers determined by refractive index matching. Biopolymers. 1986;25:2375–2384. doi: 10.1002/bip.360251214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Weisel J.W., Stauffacher C.V., Cohen C. A model for fibrinogen: domains and sequence. Science. 1985;230:1388–1391. doi: 10.1126/science.4071058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bode W., Mayr I., Hofsteenge J. The refined 1.9 A crystal structure of human alpha-thrombin: interaction with D-Phe-Pro-Arg chloromethylketone and significance of the Tyr-Pro-Pro-Trp insertion segment. EMBO J. 1989;8:3467–3475. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1989.tb08511.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li W., Sigley J., Guthold M. Fibrin fiber stiffness is strongly affected by fiber diameter, but not by fibrinogen glycation. Biophys. J. 2016;110:1400–1410. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2016.02.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ferri F., Calegari G.R., Rocco M. Size and density of fibers in fibrin and other filamentous networks from turbidimetry: beyond a revisited Carr–Hermans method, accounting for fractality and porosity. Macromolecules. 2015;48:5423–5432. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chernysh I.N., Nagaswami C., Weisel J.W. Fibrin clots are equilibrium polymers that can be remodeled without proteolytic digestion. Sci. Rep. 2012;2:879. doi: 10.1038/srep00879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kass R.E., Raftery A.E. Bayes factors. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1995;90:773–795. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Scatchard G. The attractions of proteins for small molecules and ions. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1949;51:660–672. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fredenburgh J.C., Stafford A.R., Weitz J.I. Evidence for allosteric linkage between exosites 1 and 2 of thrombin. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:25493–25499. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.41.25493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Siebenlist K.R., Mosesson M.W., Stojanovic L. Studies on the basis for the properties of fibrin produced from fibrinogen-containing gamma’ chains. Blood. 2005;106:2730–2736. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-01-0240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Müller J., Freitag D., Pötzsch B. Anticoagulant characteristics of HD1-22, a bivalent aptamer that specifically inhibits thrombin and prothrombinase. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2008;6:2105–2112. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2008.03162.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Barabas E., Szell E., Bajusz S. Screening for fibrinolysis inhibitory effect of synthetic thrombin inhibitors. Blood Coagul. Fibrinolysis. 1993;4:243–248. doi: 10.1097/00001721-199304000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Callas D., Bacher P., Fareed J. Fibrinolytic compromise by simultaneous administration of site-directed inhibitors of thrombin. Thromb. Res. 1994;74:193–205. doi: 10.1016/0049-3848(94)90108-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Warkentin T.E. Bivalent direct thrombin inhibitors: hirudin and bivalirudin. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Haematol. 2004;17:105–125. doi: 10.1016/j.beha.2004.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]