Abstract

Introduction: Regarding the limited ability of the damaged cartilage cells to self-renew, which is due to their specific tissue structure, subtle damages can usually cause diseases such as osteoarthritis. In this work, using laser photobiomodulation and an interesting source of growth factors cocktail called the synovial fluid, we analyzed the chondrogenic marker genes in treated hair follicle dermal papilla cells as an accessible source of cells with relatively high differentiation potential.

Methods: Dermal papilla cells were isolated from rat whisker hair follicle (Rattus norvegicus) and established cell cultures were treated with a laser (gallium aluminum arsenide diode Laser (λ=780 nm, 30 mW) at 5 J/cm2 ), the synovial fluid, and a combination of both. After 1, 4, 7, and 14 days, the morphological changes were evaluated and the expression levels of four chondrocyte marker genes (Col2a1, Sox-9, Col10a1, and Runx-2) were assessed by the quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction.

Results: It was monitored that treating cells with laser irradiation can accelerate the rate of proliferation of cells. The morphology of the cells treated with the synovial fluid altered considerably as in the fourth day they surprisingly looked like cultured articular chondrocytes. The gene expression analysis showed that all genes were up-regulated until the day 14 following the treatments although not equally in all the cell groups. Moreover, the cell groups treated with both irradiation and the synovial fluid had a significantly augmented expression in gene markers.

Conclusion: Based on the gene expression levels and the morphological changes, we concluded that the synovial fluid can have the potential to make the dermal papilla cells to most likely mimic the chondrogenic and/or osteogenic differentiation, although this process seems to be augmented by the irradiation of the low-level laser.

Keywords: Hair follicle dermal papilla cells, Differentiation, Laser photobiomodulation, Synovial fluid, Cartilage

Introduction

A hair follicle consists of two main regions originated from the embryonic ectoderm and the mesenchymal cells.1 The relationship between these cells is necessary for the development of many structures such as hair, teeth, etc. While the hair follicle epithelial stem cells are markedly located in a region called bulge, the mesenchymal cells are mainly in the dermal compartment which comprises the dermal papilla, a group of teardrop-shaped cells surrounded by a network of nerves and vessels, causing the activation of matrix keratinocytes through morphogenetic and mitogenic signals2 and the dermal sheath.1 The hair follicle dermal cells have maintained their embryonic-like properties to some degree because they are segregated from intrafollicular dermis relatively early on in follicle development. Given this point, it can be said that these cells are one kind of embryonic cells which have remained in the adult system.3 Therefore, the dermal papilla cells have attracted many scientists because of their potential in the regulation of development and growth, although it is assumed that they are a source of multipotent mesenchymal cells which have a high differentiation potential4 as they can differentiate into adipogenic, osteogenic,5 odontogenic,6 and myogenic lineages,7 and also repopulate the hematopoietic system.3 Besides, lineage analysis indicates that both hair and whisker follicle dermal papillae contain neural-crest-derived cells.8 Finally, among the distinctive advantages of the hair follicle cells, the property of being easily accessible9 makes these cells some attractive targets for cell therapy purposes.

To date, many scientists have reported the differentiation of mesenchymal cells toward chondrocytes occurs through several steps including the condensation of the mesenchymal chondroprogenitor cells in order to differentiate into chondrocytes. Following chondrogenesis, the chondrocytes would either undergo the resting stage and differentiate into the articular cartilage or proliferate and pass the prehypertrophic and hypertrophic stages under the effect of different factors in a process called endochondral ossification in order to form the bone.10 The mature chondrocyte is one kind of the connective tissue susceptible to injuries because of its limited abilities for self-renewal, which causes irreversible injuries; therefore, repairing the cartilage defects by a variety of methods has become an interesting subject for many studies. Osteoarthritis is one of the most prevalent degenerative joint disorders, leading to pain and disability of millions of people worldwide.11 Since treatment with medications has not led to a complete recovery, today cartilage engineering based on autologous chondrocyte implantation (ACI) brings new hopes for treating this disease.12 The purpose of ACI is to treat the cartilage lesions through the implantation of the autologous chondrocyte which has been expanded by a cell culture. However, in order to use invasive methods and overcome the problems regarding the use of chondrocytes such as the limited amount of cells obtained in biopsies, scientists have begun to focus on mesenchymal stem cells as an interesting source of cells for cartilage repair.

The low-intensity laser irradiation or photobiomodulation (PBM) therapy can cause a bio-stimulation response which leads to an increased gene expression and stem cell migration in an in vitro condition13 as it is proved that Runx-2 gene expression (a very popular gene marker for osteogenesis) will increase following the low-level laser irradiation.14 Besides, it has been shown that the low-intensity laser is useful not only in increasing the cell proliferation15 but also in accelerating the rate of the differentiation toward different cell lineages in combination with different growth factors.16-18 The increased cell proliferation and migration following the irradiation is because of the several molecular mechanisms including the inhibition of inflammatory cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), interleukin 1 beta- (IL-1β), interleukin 6 (IL-6), and interleukin 8 (IL-8), the elevated amount of nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-κB) activation, the induction of reactive oxygen species (ROS); the increased amount of inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) activity, the augmentation of cellular adenosine three phosphate (ATP) levels, the upregulation of growth factors such as platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF), insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1), nerve growth factor (NGF), transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β), and fibroblast growth factor-2 (FGF-2), the stimulation of protein kinase C (PKC) activation, the inhibition of apoptosis, and others and their corresponding signaling pathways.13,19

The synovial fluid (SF) is a very viscose fluid secreted by the synovial membrane and its main responsibility is both to lubricate the bones and to nourish the cells of cartilage tissue which does not have any blood vessels.20 SF in patients with rheumatoid diseases consists of a significant amount of hyaluronic acid and also contains lubricin, glycoproteins, growth factors (like TGF-β, FGF, and IGF-1), prolactin hormone, growth hormones, and cytokines like IL-6, Interleukin 1 (IL-1), and TNF-α.21-25, There are a number of studies evaluating the effectiveness of SF and its mesenchymal stem cells in order to relieve the chondrocytes defects.26

The aim of this study was to investigate the effect of the SF, the laser irradiation, and a combination of both on the differentiation potential of the dermal papilla cells toward chondrocyte and osteocyte lineages.

Materials and Methods

Isolation of the Dermal Papilla Cells From the Rat Whisker Hair Follicles

The rat whisker follicles were isolated as previously described.27 In brief, first, an L-shaped incision was made behind the whisker pad under a dissecting microscope. The whisker pad was inverted and fat and connective tissues were removed so the follicles were exposed. The hair follicles were dissected and placed in dissection media containing Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM; Inoclon, Iran) supplemented with 1% Antibiotics (100 U/mL penicillin and 100 μg/mL streptomycin; Gibco, USA) and 0.5 μg/mL amphotericin B (Sigma-Aldrich, USA). Then using a pair of insulin needles under a stereomicroscope in a sterile environment, the end bulbs were inverted and dermal papillae appeared. By cutting the basal stalk, which links the dermal papilla to the connective tissue, the dermal papillae were dissected from the hair follicles.

Establishment of Dermal Papilla Cell Cultures

About 6 dissected dermal papillae were pooled in the initial medium and cultured in 24 well plates in 37°C and 5% CO2. The initial medium contained Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium supplemented with 20% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Gibco, USA) and 1% antibiotics and amphotericin B as described before. The cultures were maintained for 1 week, and after that the initial medium replaced by the expansion medium contained Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium supplemented with 10% FBS, 1% antibiotics and amphotericin B. After the cell culture reached an 80% confluence, it passaged routinely. To confirm that the cultured cells are from the dermal papilla, the expression of dermal papilla gene marker alkaline phosphatase was assessed and 4 groups of cell cultures were classified:

SF treated

PBM treated

SF and PBM treated

Controls (no treatment)

Chondrogenic Differentiation

To induce the chondrogenic differentiation, cells from 3-5 passages were cultured in the differentiation medium containing DMEM supplemented with 1.5% SF, 10% FBS, 1% antibiotics and 1% amphotericin B for 1, 4, 7, and 14 days. This media was applied to the cells with each culture medium exchange. The SF used in this study was taken from children with rheumatoid arthritis (RA), diagnosed by a rheumatologist later, under an IRB-approved protocol in Mofid children’s hospital (Tehran, Iran). In order to separate the cells and other unwanted materials in SF, it was centrifuged for 5 minutes at 1500 rpm.

Laser Irradiation

The gallium aluminium arsenide (GaAlAs) diode Laser 780 nm wavelength (Transverse IND. CO., LTD., Taipei, Taiwan) used in this study was supplied and set up by the Laser and Plasma Research Institute (Shahid Beheshti University, Tehran, Iran). The laser was sterilized via flushing 70% ethanol on its surface thoroughly and it was placed in the laminar flow hood. Semi-confluent monolayers of the hair follicle dermal papilla cells were irradiated with the lids off and the medium was replaced by Phosphate buffer saline (PBS; Inoclone, Tehran, Iran) during the irradiation. The irradiation took place in 24 well plates in dark and at room temperature. It was calculated that for the output power of 30 mW it would take 5 minutes and 33 seconds to deliver 5 J/cm2 which was demonstrated to increase the RNA and protein synthesis in previous studies.28 These values were calculated using the formula E[J/cm2]=P[W] ×t[s] / A [cm2], where E representing energy, P is the output power, t is the calculated time for irradiation, and A is the area value which here is 200 mm2.

After the irradiation, some plates were incubated with the differentiation medium while the others incubated with the normal expansion medium as described before. Non-irradiated cells were used as controls and the same conditions applied to them. Both irradiated and non-irradiated samples were re-incubated at 37°C and 5% CO2 for 1, 4, 7, and 14 days. PBM treated cells were irradiated once.

RNA Extraction and Quantitative Reverse Transcription Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction (Q-RT-PCR)

Total RNA was isolated from independent biological replicates of the hair follicle dermal papilla cells, using the easy-BLUE(TM) Total RNA Extraction Kit (iNtRON Biotechnology Inc., South Korea), following the manufacturer’s instructions. RNA concentration and quality were determined by using Nano Drop (Thermo scientific, the USA) and electrophoresis on the agarose gel. On the basis of 500 μg of RNA, the first strand cDNA was synthesized by using Maxime™ RT PreMix (Oligo (dT) 15 Primer) (iNtRON Biotechnology Inc., South Korea). The ALP expression was shown via RT-PCR using Taq 2x Master Mix Red-Mgcl2 1.5 mM (Ampliqon Inc., Denmark). In order to assess the different gene expression patterns, an equal amount of the resulting cDNA was subjected to real-time PCR using a Rotor-Gene 6000 (Corbett Life Science, Sydney, Australia). The oligonucleotide primers are listed in Table 1 and beta-actin was measured as an endogenous control. The qPCR Green-Master with low ROX (PCR-316S, Jena Bioscience, Germany) was used to amplify the interested regions following the standard protocol of the supplier. For the relative quantification, a standard curve was generated by serially diluting (500, 250, 125, and 62.5 ng/uL) the pool of cDNA samples with a high expression value. The standard curve was calculated by plotting the log value of the starting concentration versus the threshold cycle (Ct). Amplification efficiencies were determined based on the slope of the standard curve using the following equation: E% = [10(– 1/slope) - 1] %, and the correlation coefficient (R2) was calculated by Rotor- Gene 6000 analysis software. The threshold cycle (Ct) and melting curves were acquired by using the quantitation and melting curve program of the Rotor-Gene 6000 analysis software.

Table 1. Primers Used in This Study .

| Genes | Primer sequences (5´-3´) | Annealing temperature (°C) | Size (bp) | Gene Bank Code |

| Col2a1 a | F: CCAGAACATCACCTACCACT R: CCCTCATCTCCACATCATTG |

60 | 109 | NM_012929.1 |

| Runx2 b | F: GGACGAGGCAAGAGTTTCAC R: GAGGCGGTCAGAGAACAAAC |

60 | 165 | NM_053470.2 |

| Col10a1 c | F: AACAGGCAGCAGCACTATG R: TGAAGCCTGATCCAAGTAGC |

58 | 183 | AJ131848.1 |

| Sox9 d | F: CTGAAGGGCTACGACTGGAC R: TACTGGTCTGCCAGCTTCCT |

60 | 140 | XM_001081628.5 |

| Beta actin | F: CTATGTTGCCCTAGACTTCG R: AGGTCTTTACGGATGTCAAC |

56 | 228 | NM_031144.3 |

| Alp e | F: CGGACCCTGCCTTACCAACTCATTTGTGC R: CCTGAGTGGTGTTGCATCGCGTGCG |

70 | 401 | NM_013059.1 |

aCollagen type II alpha 1; bRunt-related transcription factor 2; ccollagen type X alpha 1; dSRY (sex determining region Y)-box 9; eAlkaline phosphatase.

Target gene expression levels (Col2a1, Sox-9, Col10a1, and Runx-2) were normalized by the endogenous beta-actin level in each treated cell group. For comparison of the treated groups, the relative mRNA levels were subsequently normalized against the control cell group values.

Statistical Analysis

The fold change of each target gene was calculated using -∆∆Ct method (2−ΔΔCt).29 Changes in the expression of target genes in the treated cell groups which were normalized by beta actin as the internal reference gene are shown as relative up- or down-regulation in comparison with the control group. Data from real-time PCR were analyzed by unpaired t test in order to compare between two groups (each group versus the control cell group). P values ≤ 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Data were analyzed using the SPSS version 20.0 software.

Results

The Isolation and Culture of the Dermal Papilla Mesenchymal Cells

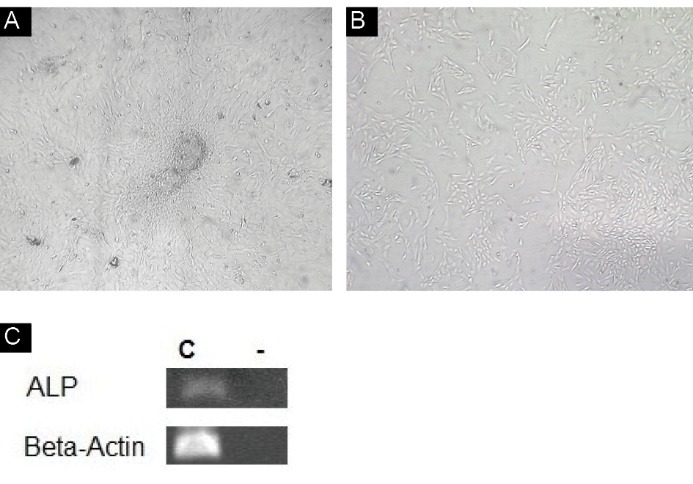

After a week the dermal papillae were attached to the plate and their cells migrated toward outside as shown in Figure 1A and B . Subculture and passage of cells have been performed 3 weeks after isolation. The RT-PCR analysis of control cells without any treatment showed the ALP expression (Figure 1C).

Figure 1.

(A) Cells during migration (×4). (B) Cell culture at passage 3 (×10). (C) The alkaline phosphatase mRNA detected by RT-PCR (C: control group without treatment -: control negative).

Cell Morphology

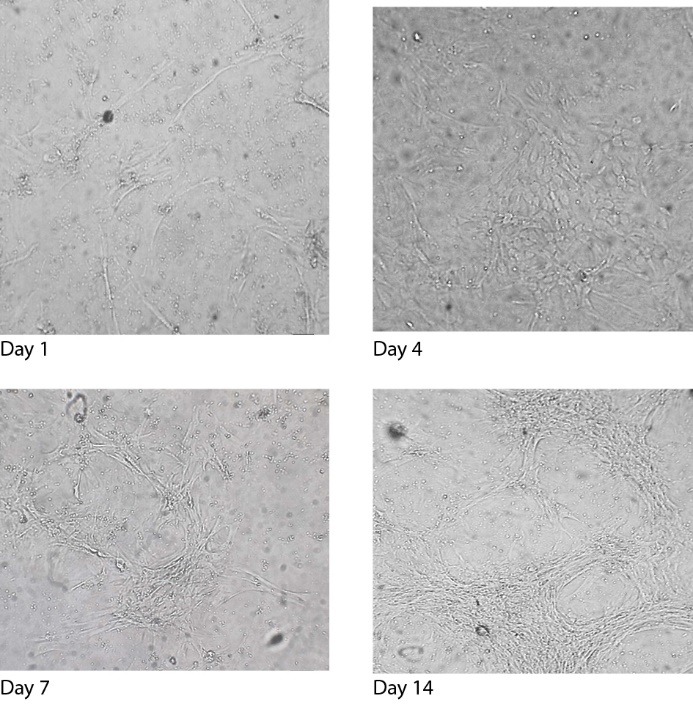

The Morphological Changes in Cells Treated With the Synovial Fluid

Following the treatment of dermal papilla cell cultures with the SF, the morphology of the cells altered dramatically from day 1 to day 14 (Figure 2). During the initial days of treatment until day 4, the cells displayed the characteristic cobblestone morphology under a phase contrast microscope and on day 4 the cells significantly looked like mouse primary cultured rib and articular chondrocytes.30 During the last days from day 7 to day 14, the cells produced an even more pronounced morphological alteration as cells started to become exceedingly long. It is notable that the cells connect to each other and form tissues patterns as this demonstrated (Figure 2). Generally, on day 14 the maximal morphological response in the cells was monitored.

Figure 2.

The Effect of the SF on the Morphology of the Dermal Papilla Cells on Day 1, Day 4, Day 7, and Day 14 (×40).

The Effect of the Laser Irradiation on the Cells in Comparison With the Cells in the Control Group

By applying the GaAlAs diode Laser (λ=780 nm, 30 mW) at 5 J/cm2 for 5 minutes and 33 seconds, an increased proliferation rate was detected using trypan blue along with the hemocytometer to determine the changes in the cell number in the treated group compared to the control group which was in the same condition as the irradiated cells. The morphological shape of the cells did not change significantly until day 14 under the treatment of the laser irradiation.

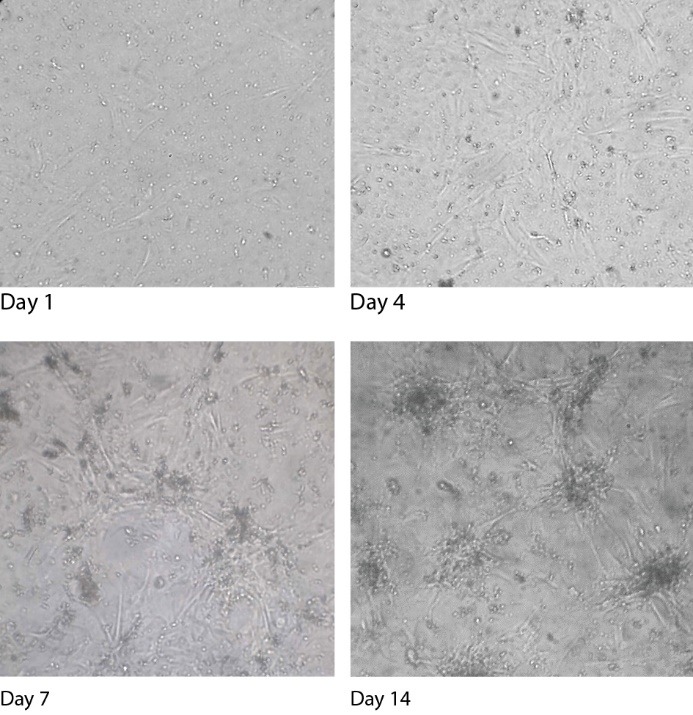

The Morphological Changes in the Cells Treated With the SF and the Laser Irradiation

The cells morphology altered significantly and rapidly, showing the effect of the laser irradiation in combination with the SF on inducing differentiation and proliferation (Figure 3). However, the differentiated morphology in the first group was much more obvious as here the characteristic morphology was not monitored and the same differentiating pattern was not repeated.

Figure 3.

The effect of the SF and the Laser Irradiation on the Morphology of the Dermal Papilla Cells on Day 1, Day 4, Day 7, and Day 14 (×40).

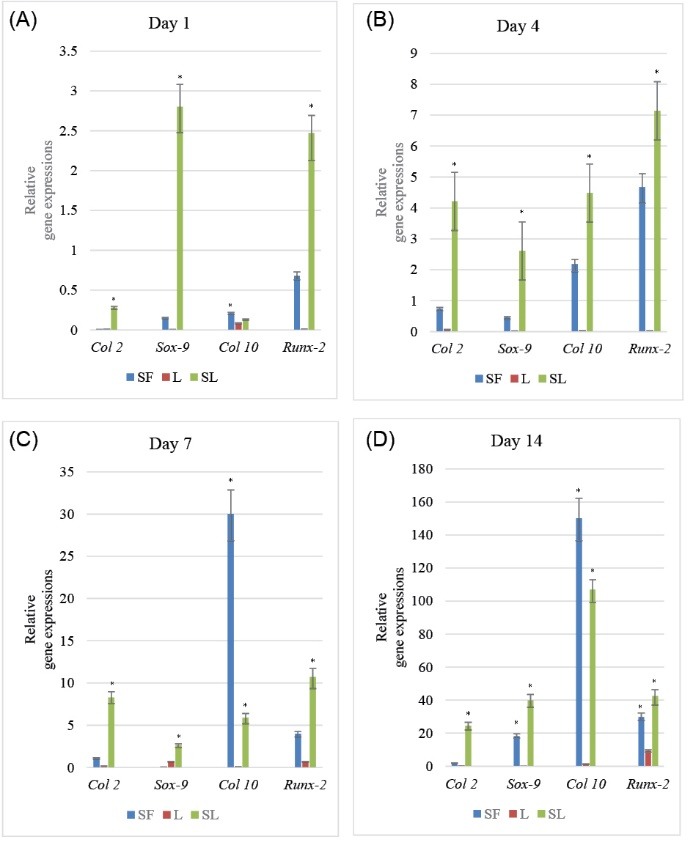

Analysis of Gene Expression in Each Group by Real-Time PCR

Real-time PCR was used to compare the expression levels of each target gene (Col2a1, Sox-9, Col10a1, and Runx-2) in the treated cell groups to those in the control cell groups. Although all genes were up-regulated until day 14 following the treatments, it was not equal for all cell groups and our results showed a similar expression pattern in Sox-9 and Col2a1 genes and also in Runx-2 and Col10a1 genes as their up-regulation was alike (Figure 4 A, B, C, and D).

Figure 4.

The Relative Expression of Each Gene Considering Time. For comparison, target gene expression levels (Col2a1, Sox-9, Col10a1, and Runx-2) were normalized by the endogenous beta-actin level in each treated cell group and subsequently normalized against the control cell group values. Bars show the mean. Gene expression levels are expressed as fold change from each group. * P < 0.05 versus controls.

The sox-9 gene expression in the group treated with just SF and the one treated with a combination of both SF and laser irradiation was slightly up-regulated, especially between the days 7 and 14. However, the group treated with just the laser irradiation had the lowest amount of gene expression. The expression of Col2a1 gene in all groups was relatively similar to the Sox-9 expression pattern.

Runx-2 and Col10a1 gene expressions had the highest expression values on days 7 and 14. Runx-2 gene was highly up-regulated on days 7 and 14 in the laser irradiated cell group and on days 4, 7, and 14 in the third group in comparison with the other genes. Besides, its expression on days 1 and 4 in the SF treated cell group was surprisingly higher than the others. In the laser irradiated cell group, Col10a1 gene expression was not mentionable (Figures 4A-D).

Discussion

It is assumed that the dermal papilla cells are a source of multipotent mesenchymal cells with high differentiation potential. Oliver in 1967 using dissected DP and Jahoda et al in 1984 using the dermal papilla cell cultures could induce whisker hair follicle neogenesis in rats.31,32 Later, other researches also started to work on these cells. For instance, in 2002, it was shown that the dermal compartments of the hair follicle can repopulate the mouse hematopoietic system.3 Further investigations showed the differentiation potential of these cells toward adipogenic, osteogenic, myogenic, and neurogenic lineages.5,7,33 Finally, using an inductive microenvironment, Gang et al. demonstrated odontogenic potential of the cultured vibrissae follicle dermal papilla cells.6 In fact, it seems that the hair follicle dermal papilla cells are an important repository of the stem cells with a high degree of plasticity and a striking regenerative capacity. In this study, we analyzed the chondrogenic potential of these cells.

The factors involved in the process of the differentiation of mesenchymal cells toward chondrocytes and osteocytes mostly include the cytokines,34 the growth factors,35 the signaling proteins, the components of an extra cellular matrix (ECM), and the transcription factors.12 There is a complex network between these factors, which determines the final destination of the cells. 36 In our study, we investigated the changes of four important chondrogenesis and Osteogenesis gene markers Sox-9, Col2a1, Runx-2, and Col10a1- as the result of treating the cultured dermal papilla cells with the SF, the laser irradiation and a combination of both.

Our results showed a similar expression pattern between Sox-9 and Col2a1 genes and also between Runx-2 and Col10a1 genes as their up-regulation was alike in the cell groups. In vitro and in vivo analyses indicated that there were chondrocyte-specific regulatory sequences in the first intron of the Col2a1 gene which included four imperfect Sox-9 binding sites.37 On the other hand, Runx-2 is a known transcription factor for osteoblastic differentiation and one of its directional targets is the collagen type 10 gene. It has been identified that there are two Runx2 putative tandem-repeat binding sites within the 3′-end of a 150-bp region in a Col10a1 distal promoter.38 Also, it has been shown that there is a regulatory element upstream of the Col10a1 gene that upregulates its expression in hypertrophic chondrocyte. This element also has a dual role and may interact with a conserved sequence in Sox-9.39 The Sox-9 gene expression patterns in the first group treated with just the SF and in the third one treated with a combination of both the SF and the laser irradiation were similar as they were slightly up-regulated, especially between the days 7 and 14 while having the lowest amount of gene expression in the laser irradiated cells. This increase may be due to the factors in the SF like FGF, TGF-β, and IGF-1 that can up-regulate the Sox-9 gene. It is shown that FGF increases the expression of Sox-9 gene in both the chondrocytes and the undifferentiated mesenchymal cells while it inhibits the proliferating stage.40 Moreover, it has been revealed that IGF-1 induces the expression of Sox-9 and inhibits the matrix metalloproteinase-13 (MMP-13) which degrades the collagen type 2.12 TGF-β is a positive regulator of chondrogenic cell determination by controlling the Sox-9 gene expression. Besides, it causes an increase in the generation of ECM components like collage type 2. The role of TGF-beta in regulating terminal differentiation can be variable and context-dependent.41 While it has also been shown that IL-6 in the SF can elevate the Col2a1 expression,42 it is assumed that the increased level of Sox-9 and Col2a1 gene expressions is because of the differentiating media that was added to the cell culture with every exchange of the medium, and it can be the reason why their expressions stayed high even on the last days. The very slight up-regulation of Sox-9 gene expression in the laser irradiated group can be due to the fact that following the irradiation the hypoxia caused by ROS generation increased the nuclear accumulation of Hypoxia-inducible factor 1-alpha (HIF-1a) and activated the Sox-9 promoter. Besides, it has also been reported that the mRNA level of Sox-9 and Col2a1 have increased after the laser irradiation.43

Runx-2 and Col10a1 gene expressions had the highest expression values on days 7 and 14, which can be inferred that these days were closer to osteoblastic differentiation as it was shown that in the prehypertrophic and hypertrophic cells the expression of Col10a1 and its regulatory transcription factor Runx-2 increased significantly. The Runx-2 gene had a higher expression value in the laser irradiated cell group on days 7 and 14 and in the third group on days 4, 7, and 14 in comparison with the other genes. It is shown that the irradiation improves the osteogenic differentiation and the expression of its correlated markers such as Runx-2 transcription factor 14,44. Besides, our results also showed that the amount of Runx-2 gene expression in the SF treated cell group on days 1 and 4 was surprisingly higher than the others. It has been indicated that there is an increased amount of endogenous FGF-2 in the SF of RA patients and that FGF2 signaling can increase RUNX-2 activity through the MEK/ERK pathway.23,45 Runx-2 also exerts reciprocal inhibition to Sox-9 transactivity and it can be one of the causes of the reduced amount of Sox-9 and its target gene Col2a1 in comparison with Runx-2 and Col10a1 gene expressions.46 In the laser irradiated cell group, the Col10a1 gene expression was not as high as the other groups. Although it has been reported that the low-level laser irradiation up-regulates the osteogenic differentiation, it is inferred that some of the activated pathways by the irradiation in the cell would cause the Col10a1 gene to be inhibited. It has been shown that in the lung fibroblasts, hepatocyte growth factor can inhibit the collagen47 and it was described elsewhere that the hepatocyte growth factor receptor is highly activated via the low-level laser irradiation13 and this may be the cause of the lower expression of the Col10a1 gene in comparison with Runx-2 in the laser irradiated cell group.

Conclusion

In conclusion, we can say that using the SF would cause the dermal papilla cells to most likely mimic the chondrogenic differentiation, and this process seems to be augmented by the irradiation of the low-level laser. In this article, we believe that cells at 7 and 14 days are going through prehypertrophic and hypertrophic stages and the first days phenotypes are resemblance of chondrogenic phase of reprogramming. However, additional analysis still has to be done. For the future studies, besides doing some additional experiments, our laboratory intends to autologously transplant these differentiated cells into the injured cartilage or bone in mice in order to examine their therapeutic potential for repairing the damaged articular cartilage and bone.

Ethical Considerations

The informed consent was obtained from children’s parents. All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

This study was performed in accordance with the National Institute of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and approved by the institutional animal care and use committee in Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Science (Tehran, Iran).

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare there are no conflicts of interest regarding the publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Prof CAB Jahoda in the School of Biological and Biomedical Sciences of Durham University for his valuable instructions and also Children Mofid Hospital for their help throughout the course of this work.

Please cite this article as follows: Farivar S, Ramezankhani R, Mohajerani E, Ghazimoradi MH, Shiari R. Gene expression analysis of chondrogenic markers in hair follicle dermal papillae cells under the effect of laser photobiomodulation and the synovial fluid. J Lasers Med Sci. 2019;10(3):171-178. doi:10.15171/jlms.2019.27.

References

- 1.Yang CC, Cotsarelis G. Review of hair follicle dermal cells. J Dermatol Sci. 2010;57(1):2–11. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2009.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Paus R, Cotsarelis G. The biology of hair follicles. N Engl J Med. 1999;341(7):491–497. doi: 10.1056/nejm199908123410706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lako M, Armstrong L, Cairns PM, Harris S, Hole N, Jahoda CA. Hair follicle dermal cells repopulate the mouse haematopoietic system. J Cell Sci. 2002;115(Pt 20):3967–3974. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Driskell RR, Clavel C, Rendl M, Watt FM. Hair follicle dermal papilla cells at a glance. J Cell Sci. 2011;124(Pt 8):1179–1182. doi: 10.1242/jcs.082446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jahoda CA, Whitehouse J, Reynolds AJ, Hole N. Hair follicle dermal cells differentiate into adipogenic and osteogenic lineages. Exp Dermatol. 2003;12(6):849–859. doi: 10.1111/j.0906-6705.2003.00161.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wu G, Deng ZH, Fan XJ. et al. Odontogenic potential of mesenchymal cells from hair follicle dermal papilla. Stem Cells Dev. 2009;18(4):583–589. doi: 10.1089/scd.2008.0066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rufaut NW, Goldthorpe NT, Wildermoth JE, Wallace OA. Myogenic differentiation of dermal papilla cells from bovine skin. J Cell Physiol. 2006;209(3):959–966. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fernandes KJ, McKenzie IA, Mill P. et al. A dermal niche for multipotent adult skin-derived precursor cells. Nat Cell Biol. 2004;6(11):1082–1093. doi: 10.1038/ncb1181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Maekawa M, Yamada K, Toyoshima M. et al. Utility of Scalp Hair Follicles as a Novel Source of Biomarker Genes for Psychiatric Illnesses. Biol Psychiatry. 2015;78(2):116–125. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2014.07.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goldring MB. Chondrogenesis, chondrocyte differentiation, and articular cartilage metabolism in health and osteoarthritis. Ther Adv Musculoskelet Dis. 2012;4(4):269–285. doi: 10.1177/1759720x12448454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pelttari K, Barbero A, Martin I. A potential role of homeobox transcription factors in osteoarthritis. Ann Transl Med. 2015;3(17):254. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2305-5839.2015.09.44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Demoor M, Ollitrault D, Gomez-Leduc T. et al. Cartilage tissue engineering: molecular control of chondrocyte differentiation for proper cartilage matrix reconstruction. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2014;1840(8):2414–2440. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2014.02.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gao X, Xing D. Molecular mechanisms of cell proliferation induced by low power laser irradiation. J Biomed Sci. 2009;16:4. doi: 10.1186/1423-0127-16-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Petri AD, Teixeira LN, Crippa GE, Beloti MM, de Oliveira PT, Rosa AL. Effects of low-level laser therapy on human osteoblastic cells grown on titanium. Braz Dent J. 2010;21(6):491–498. doi: 10.1590/s0103-64402010000600003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Farivar S, Malekshahabi T, Shiari R. Biological Effects of Low Level Laser Therapy. Journal of Lasers in Medical Sciences. 2014;5(2):58–62. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Soleimani M, Abbasnia E, Fathi M, Sahraei H, Fathi Y, Kaka G. The effects of low-level laser irradiation on differentiation and proliferation of human bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells into neurons and osteoblasts--an in vitro study. Lasers Med Sci. 2012;27(2):423–430. doi: 10.1007/s10103-011-0930-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stein A, Benayahu D, Maltz L, Oron U. Low-level laser irradiation promotes proliferation and differentiation of human osteoblasts in vitro. Photomed Laser Surg. 2005;23(2):161–166. doi: 10.1089/pho.2005.23.161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.de Villiers JA, Houreld NN, Abrahamse H. Influence of low intensity laser irradiation on isolated human adipose derived stem cells over 72 hours and their differentiation potential into smooth muscle cells using retinoic acid. Stem Cell Rev. 2011;7(4):869–882. doi: 10.1007/s12015-011-9244-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kushibiki T, Hirasawa T, Okawa S, Ishihara M. Low Reactive Level Laser Therapy for Mesenchymal Stromal Cells Therapies. Stem Cells International. 2015;2015:12. doi: 10.1155/2015/974864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Trosko JE, Chang CC. Isolation and characterization of normal adult human epithelial pluripotent stem cells. Oncol Res. 2003;13(6-10):353–357. doi: 10.3727/096504003108748366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Houssiau FA, Devogelaer JP, Van Damme J, de Deuxchaisnes CN, Van Snick J. Interleukin-6 in synovial fluid and serum of patients with rheumatoid arthritis and other inflammatory arthritides. Arthritis Rheum. 1988;31(6):784–788. doi: 10.1002/art.1780310614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mannami K, Mitsuhashi T, Takeshita H. et al. Concentration of interleukin-1 beta in serum and synovial fluid in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and those with osteoarthritis. Nihon Seikeigeka Gakkai Zasshi. 1989;63(11):1343–1352. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Manabe N, Oda H, Nakamura K, Kuga Y, Uchida S, Kawaguchi H. Involvement of fibroblast growth factor-2 in joint destruction of rheumatoid arthritis patients. Rheumatology (Oxford) 1999;38(8):714–720. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/38.8.714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brennan FM, Chantry D, Turner M, Foxwell B, Maini R, Feldmann M. Detection of transforming growth factor-beta in rheumatoid arthritis synovial tissue: lack of effect on spontaneous cytokine production in joint cell cultures. Clin Exp Immunol. 1990;81(2):278–285. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1990.tb03331.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tavera C, Abribat T, Reboul P. et al. IGF and IGF-binding protein system in the synovial fluid of osteoarthritic and rheumatoid arthritic patients. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 1996;4(4):263–274. doi: 10.1016/s1063-4584(05)80104-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.de Sousa E, Casado P, Neto V, Duarte M, Aguiar D. Synovial fluid and synovial membrane mesenchymal stem cells: latest discoveries and therapeutic perspectives. Stem Cell Research & Therapy. 2014;5(5):1–6. doi: 10.1186/scrt501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gledhill K, Gardner A, Jahoda CA. Isolation and establishment of hair follicle dermal papilla cell cultures. Methods Mol Biol. 2013;989:285–292. doi: 10.1007/978-1-62703-330-5_22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Greco M, Guida G, Perlino E, Marra E, Quagliariello E. Increase in RNA and protein synthesis by mitochondria irradiated with helium-neon laser. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1989;163(3):1428–1434. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(89)91138-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. 2001;25(4):402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gosset M, Berenbaum F, Thirion S, Jacques C. Primary culture and phenotyping of murine chondrocytes. Nat Protoc. 2008;3(8):1253–1260. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Oliver RF. The experimental induction of whisker growth in the hooded rat by implantation of dermal papillae. J Embryol Exp Morphol. 1967;18(1):43–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jahoda CA, Horne KA, Oliver RF. Induction of hair growth by implantation of cultured dermal papilla cells. Nature. 1984;311(5986):560–562. doi: 10.1038/311560a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hunt DP, Morris PN, Sterling J. et al. A highly enriched niche of precursor cells with neuronal and glial potential within the hair follicle dermal papilla of adult skin. Stem Cells. 2008;26(1):163–172. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-0281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jagielski M, Wolf J, Marzahn U. et al. The influence of IL-10 and TNFalpha on chondrogenesis of human mesenchymal stromal cells in three-dimensional cultures. Int J Mol Sci. 2014;15(9):15821–15844. doi: 10.3390/ijms150915821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Danisovic L, Varga I, Polak S. Growth factors and chondrogenic differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells. Tissue Cell. 2012;44(2):69–73. doi: 10.1016/j.tice.2011.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zuscik MJ, Hilton MJ, Zhang X, Chen D, O’Keefe RJ. Regulation of chondrogenesis and chondrocyte differentiation by stress. J Clin Invest. 2008;118(2):429–438. doi: 10.1172/jci34174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Akiyama H. Control of chondrogenesis by the transcription factor Sox9. Mod Rheumatol. 2008;18(3):213–219. doi: 10.1007/s10165-008-0048-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li F, Lu Y, Ding M. et al. Runx2 contributes to murine Col10a1 gene regulation through direct interaction with its cis-enhancer. J Bone Miner Res. 2011;26(12):2899–2910. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Leung VYL, Gao B, Leung KKH. et al. SOX9 Governs Differentiation Stage-Specific Gene Expression in Growth Plate Chondrocytes via Direct Concomitant Transactivation and Repression. PLoS Genet. 2011;7(11) doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sahni M, Ambrosetti DC, Mansukhani A, Gertner R, Levy D, Basilico C. FGF signaling inhibits chondrocyte proliferation and regulates bone development through the STAT-1 pathway. Genes Dev. 1999;13(11):1361–1366. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.11.1361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.van der Kraan PM, Blaney Davidson EN, Blom A, van den Berg WB. TGF-beta signaling in chondrocyte terminal differentiation and osteoarthritis: modulation and integration of signaling pathways through receptor-Smads. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2009;17(12):1539–1545. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2009.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Namba A, Aida Y, Suzuki N. et al. Effects of IL-6 and soluble IL-6 receptor on the expression of cartilage matrix proteins in human chondrocytes. Connect Tissue Res. 2007;48(5):263–270. doi: 10.1080/03008200701587513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kushibiki T, Tajiri T, Ninomiya Y, Awazu K. Chondrogenic mRNA expression in prechondrogenic cells after blue laser irradiation. J Photochem Photobiol B. 2010;98(3):211–215. doi: 10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2010.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fujimoto K, Kiyosaki T, Mitsui N. et al. Low-intensity laser irradiation stimulates mineralization via increased BMPs in MC3T3-E1 cells. Lasers Surg Med. 2010;42(6):519–526. doi: 10.1002/lsm.20880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang X, Manner PA, Horner A, Shum L, Tuan RS, Nuckolls GH. Regulation of MMP-13 expression by RUNX2 and FGF2 in osteoarthritic cartilage. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2004;12(12):963–973. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2004.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cheng A, Genever PG. SOX9 determines RUNX2 transactivity by directing intracellular degradation. J Bone Miner Res. 2010;25(12):2680–2689. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bogatkevich GS, Ludwicka-Bradley A, Highland KB. et al. Down-regulation of collagen and connective tissue growth factor expression with hepatocyte growth factor in lung fibroblasts from white scleroderma patients via two signaling pathways. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56(10):3468–3477. doi: 10.1002/art.22874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]