Abstract

Background:

Health care workers (HCW) are at high risk of contracting various infectious diseases and play a dual role in the transmission of infections in health care facilities.

Objective:

To determine the seroprotection against hepatitis B, measles, rubella, and varicella among HCWs in a community hospital in Qatar.

Methods:

This is a cross-sectional survey conducted in a 75-bed community hospital in Dukhan, Qatar. From August 2012 to December 2015, 705 HCWs were tested for the presence of IgG antibodies for measles, rubella, and varicella, and also for hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg). They were also asked about previous history of hepatitis B vaccination.

Results:

595 (84.4%) HCWs received a full hepatitis B vaccination schedule; 110 (15.6%) received a single dose. The full schedule was reported with higher frequency by nurses (90.2%) compared to physicians (74.1%) or technicians (79.7%). Those aged ≥30 years (90.4%) and <20 years of work experience had received a full vaccination schedule more frequently than younger and less experienced HCWs. Female HCWs (87.8%) received full schedule more frequently than males (78.8%). 73.4% of the staff had seroprotection against heaptitis B, with the lowest anti-HBsAg titers observed in physicians (58.8%) compared with other categories; males (64.9%) were less protected than females. The seropositivity was 85.6%(95% CI 82.4% to 88.4%) for measles, 94.7% (95% CI 92.2% to 97.3%) for rubella, and 92.2% (95% CI 89.7% to 94.7%) for varicella.

Conclusion:

HCWs, particularly physicians, are not enough protected against hepatitis B. The seroprotection against measles, rubella, and varicella.

Keywords: Hepatitis B, Measles, Rubella, Chickenpox, Seroepidemiologic studies, Vaccines, Cuba

TAKE-HOME MESSAGE

Immunization of health care workers against selected diseases is strongly recommended, taking into account the high risk of exposure to blood, secretions or body fluids or other potentially contaminated environmental sources of microbial agents potentially vaccine-preventable.

In Qatar, the incidence of vaccine-preventable diseases is low in native population but cases are reported from expatriate population, mainly from countries with high incidence of these diseases.

The serological results have shown high figures of seroprotection for rubella, varicella, measles, and hepatitis B.

Introduction

The health care workers (HCW) play a dual role in the transmission of infection in health care facilities. They can acquire infectious diseases from patients or serve as a source of infection for patients, with a wide range of infectious agents involved in this transmission. Among these, vaccine-preventable diseases like hepatitis B, measles, rubella, varicella (chickenpox), etc, are included. Immunization of HCWs against selected diseases is strongly recommended, taking into account the high risk of exposure they have to blood, secretions or body fluids or other potentially contaminated environmental sources by microbial agents potentially vaccine-preventable.1-3

HCWs have an elevated risk of acquiring hepatitis B and C through percutaneous or mucosal exposures to infected blood, which occur in the health care setting, most often as a needle stick or other sharp injuries. It is estimated that HCWs receive 400000 percutaneous injuries annually. Occupational exposures to hepatitis B virus have historically accounted for as many as 4.5% of the acute hepatitis B cases reported in the USA.4 The risk of acquired hepatitis B infection, after a single exposure to hepatitis B virus-infected blood or body fluid, ranges from 6% to 30% with increased risk attributed to repeated exposure.2 Even though it is rare, the transmission from an infected HCW to patients has been reported for hepatitis B, as well as for other vaccine-preventable diseases1. Hepatitis B vaccination is currently recommended or mandated for HCWs worldwide.2,3 Therefore, the vaccine coverage and the seroprotection against hepatitis B constitute areas of concern and quality improvements in many settings.5-14

Recent studies conducted in HCWs show variable prevalence of seropositivity, between 54% and 97%, against measles, rubella, and varicella in Emirati medical students4 and Turkey's HCWs15. Similar results were reported in studies from Egypt, Japan, Australia and Italy.16

In Qatar, the incidence of vaccine-preventable diseases is low in native population but cases are reported from expatriate population, mainly from countries with high incidence of these diseases.17 On the other hand, the health care force in the country is multinational and from countries with diverse vaccine coverage and incidence of vaccine-preventable diseases. At national level, evaluation of the immune status for vaccine-preventable diseases is mandatory during pre-employment of HCWs.

We conducted this cross-sectional study to determine seroprotection against hepatitis B, measles, rubella, and varicella among HCWs in a community hospital in Qatar.

Materials and Methods

This cross-sectional study was conducted in the Cuban Hospital, a 75-bed community hospital located in Dukhan, Qatar. Between August 2012 and December 2015, all new deputed medical staff (Cuban nationality) underwent a pre-employment medical evaluation, as per corporate regulations, which included the evaluation of health and immunization history and laboratory tests for measles, rubella, varicella, and hepatitis B. Data on age, sex, job category (physician, nurse, allied health care professional) and length of employment as a HCW, were collected from the staff register.

The collected sera were tested for the presence of IgG antibodies specific for measles, rubella, and varicella using Enzygnost® anti-measles-virus/IgG, Architect system/Rubella IgG, and BIO-RAD-PlateliaTM VZV IgG, respectively. According to the manufacturers' recommendations, measles antibody titres <100 mIU/mL were considered “non-protective” or “negative,” those between 100 and 200 mIU/mL were considered “equivocal,” and titers >200 mIU/mL were considered “immune protection” or “positive” results. For rubella the cut-off values were ≤4.9 IU/mL (negative), 5–9.9 IU/mL (equivocal) and ≥10.0 IU/mL (positive); and for varicella the cut-off points were <0.8 IU/mL (negative), 0.8–1.2 IU/mL (equivocal) and >1.2 IU/mL (positive).

Sera were tested by standard ELISA (Architect, Abbot) for HBsAb; a titer ≥10 IU/L was considered “positive (protected),” otherwise, it was “negative (non-protected).”

Receiving a minimum of three doses of heaptitis B vaccine, as per national immunization program, was considered “full hepatitis B vaccination schedule.” Receiving a single dose of the vaccine was considered “incomplete schedule.” Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed with JMP 5.1 (SAS Institute, www.jmp.com) and Epidat 3.1 (www.sergas.es/Saude-publica/EPIDAT-3-1). The prevalence of seroprotection as well as its 95% confidence interval were calculated. Categorical and continuous variables were analyzed with χ2 and Student's t test, respectively. A p value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

The studied 705 HCWs were consisted of 400 nurses, 177 physicians, and 128 allied HCWs. There were 448 females and 257 males, mostly aged between 30 and 49 years (83.9%), with >10 years of work experience as a HCW (89.4%) (Table 1).

| Table 1: Characteristics of health care workers by hepatitis B vaccination and anti-HBsAb, measles, rubella, and varicella. | ||||||||

| Variables | n | Seroprevalence % (95% CI) | Hepatitis B vaccination (%) | |||||

| Hepatitis B | Measles | Rubella | Varicella | Full schedule | Single dose | |||

| Job Category | ||||||||

| Nurse | 400 | 78.1 (75.1 to 81.2) | 83.9 (79.5 to 88.3) | 95.8 (93.0 to 98.6) | 91.1 (87.7 to 94.6) | 90.2** | 28.1 | |

| Physician | 177 | 58.8 (55.2 to 62.4)** | 93.8 (88.9 to 98.7)* | 93.8 (82.8 to 98.7) | 97.3 (92.3 to 99.4) | 74.1 | 34.5 | |

| Technician | 128 | 77.3 (74.2 to 80.4) | 80.5 (71.3 to 89.7) | 91.1 (80.4 to 97.0) | 89.3 (82.1 to 96.5) | 79.7 | 17.1 | |

| Age (yrs) | ||||||||

| <30 | 31 | 82.8 (80.0 to 85.5) | 81.5 (61.9 to 93.7) | 88.0 (68.8 to 97.5) | 93.1 (77.2 to 99.1) | 71.0 | 22.6 | |

| 30–39 | 304 | 82.7 (79.9 to 85.5)* | 79.0 (73.5 to 84.6) | 96.1 (93.7 to 97.5) | 89.8 (85.7 to 84.0) | 90.4* | 24.2 | |

| 40–49 | 288 | 62.9 (59.3 to 66.5) | 91.1 (86.9 to 95.3)** | 93.3 (88.3 to 98.2) | 93.5 (89.8 to 97.2) | 79.6 | 31.2 | |

| ≥50 | 82 | 66.7 (63.2 to 70.2) | 100 | 95.2 (76.2 to 99.9) | 100 | 83.8 | 31.1 | |

| Work experience (yrs) | ||||||||

| <5 | 10 | 87.5 (85.1 to 89.9)** | 100 | 71.4 (29.0 to 96.3) | 75.0 (35.0 to 96.8) | 80.0 | 20.0 | |

| 5–9 | 65 | 76.0 (72.9 to 79.2) | 80.5 (67.1 to 93.8) | 94.1 (80.3 to 99.3) | 90.7 (77.9 to 97.4) | 82.8 | 18.8 | |

| 10–19 | 371 | 77.5 (74.4 to 80.6) | 81.8 (77.0 to 86.6) | 96.1 (93.2 to 98.9 | 90.7 (87.1 to 94.4) | 88.2** | 26.4 | |

| 20–29 | 198 | 63.9 (60.4 to 67.5) | 90.7 (85.6 to 95.9) | 91.8 (84.8 (98.8) | 95.0 (90.8 to 99.0) | 76.6 | 30.2 | |

| ≥30 | 61 | 71.9 (68.6 to 75.2) | 100 | 100 | 100 | 89.3 | 39.3 | |

| Sex | ||||||||

| Female | 448 | 77.7 (74.6 to 80.8)** | 86.3 (78.5 to 90.2) | 88.0 (68.8 to 97.5) | 92.6 (88.3 to 96.9) | 87.8** | 26.3 | |

| Male | 257 | 64.9 (61.4 to 68.4) | 84.3 (82.4 to 90.2) | 95.3 (92.8 to 97.8) | 92.0 (88.9 to 95.1) | 78.8 | 30.2 | |

| Total | 705 | 74.2 (71.0 to 77.4) | 85.6 (82.4 to 88.4) | 94.7 (92.2 to 97.3) | 92.2 (89.7 to 94.7) | 84.4 | 15.6 | |

| *p< 0.05; **p< 0.001 | ||||||||

Of 705 HCWs studied, 595 (84.4%) workers received a full hepatitis B vaccination schedule; 110 (15.6%) received a single dose out of whom, 85 (77.3%) had incomplete vaccination schedule, while 25 (22.7%) received booster doses. The full schedule was reported with significantly (p<0.001) higher frequency by nurses (90.2%) compared with physicians (74.1%) and technicians (79.7%). Those aged ≥30 years (90.4%) (p=0.03) with <20 years of work experience (p<0.001) had received full vaccination schedule more frequently than younger and less experienced HCWs. Female HCWs (87.8%) received full schedule more frequently (p=0.001) than males (78.8%) (Table 1).

Almost three-quarters (73.4%, 95% CI 70.1% to 76.7%) of the studied HCWs had seroprotection against hepatitis B, lowest anti-HBsAb titers were recorded in physicians (58.8%) (p<0.001) compared with other job categories; males (64.9%) were less protected than females (p=0.001). The younger and less-experienced HCWs had a significantly higher anti-HBsAb titers, with less seroprotection in HCWs aged >40 years and >5 years work experience. Those with seroprotection had a mean age of 39.4 (SD 6.6) years and a mean work experience as a HCW of 16.9 (SD 6.9) years (Table 1). Of those with seroprotection, 154 HCWs had anti-HBsAb between 10 and 100 mIU/mL, 369 had titers >100 mIU/mL.

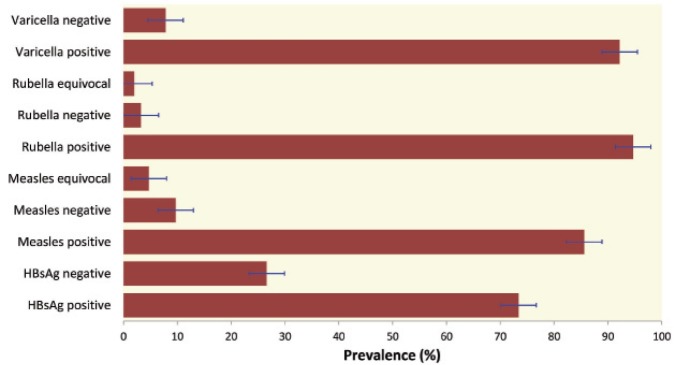

Figure 1 shows seroprevalence of the studied diseases. The highest prevalence is that of rubella (94.7%) followed by varicella (92.2%), and measles (85.6%). The seropositivity rate of measles in physicians (93.8%) was significantly (p=0.04) higher than nurses (83.9%) and allied HCWs (80.5%). Those aged >40 years were more seropositive than 30–39-year-old workers (79.0%) (p<0.001) and HCWs aged <29 years (81.5%) (p=0.02). Seropositive HCWs had a mean age of 40.5 (SD 6.5) years, significantly (p=0.03) higher than those with seronegative (mean 36.9, SD 4.5) or equivocal (mean 36.8, SD 4.5) test results (Table 1). Similarly, seropositive HCWs had a significantly (p=0.04) longer work experience (mean 17.9, SD 7.1 years) than those with seronegative (mean 15.0, SD 5.7) or equivocal (mean 14.0, SD 4.1) test results.

Figure 1.

Seroprevalence of hepatitis B, measles, rubella, and varicella among studied health care workers. Error bars represent 95% confidence interval.

No significant difference was observed in seroprevalence of rubella and varicella (94.7% and 92.2%, respectively). The only exception was the significant (p=0.04) predominance of varicella seropositive rate in HCWs with higher age (mean 40.0, SD 6.5 years) and longer service (mean 17.6, SD 7.0) (Table 1). There were no significant sex-related differences in the seropositivity for these diseases.

Discussion

The coverage of hepatitis B vaccination and the frequency of non-immune staff in the HCWs studied were acceptable. Byrd, et al, reported that 63.4% of HCWs reported receiving ≥3 doses of HepB vaccine.14 Lower rates were reported from Tanzania (48.8%) and Mexico (52.0%).6,9 The deficiency in vaccination coverage was attributed to several factors including refusal to vaccination for fear of adverse events, low-risk perception, doubt about efficacy, unavailability of free of charge services, etc. The low percentage (15.6%) of the HCWs who received only a single dose of the vaccine was mainly attributed to interrupted vaccination schedule. This would be prevented by raising the awareness of HCWs, improving the management system and increasing supervision. For example, a recently published paper reports the effect of employing a multifaceted program on influenza vaccine coverage.18

The observation of higher hepatitis B vaccination coverage in nurses (predominantly females) compared with physicians and technicians, is most likely due to individual factors (eg, risk perception) or greater focus on vaccination programs for specific occupational categories. Similarly, the increased coverage among older HCWs might be a reflection of the performance of the vaccination program.

The prevalence of anti-HBsAb among medical school students in Italy was reported to be (84.2%). It was 76.2% among Saudis HCWs, and 53.0% in Laos HCWs.5,10,12

The observed frequency of HCWs without protective levels anti-HBsAb was primarily attributed to deficiencies in vaccination coverage. Nevertheless, there is evidence showing that the vaccine is protective if the anti-HBsAb titer once rises to a level above 10 IU/L, and that the protection persists even if the antibody levels decline below 10 IU/L.

The prevalence of seroprotection for measles, rubella, and varicella in HCWs was similar to other published reports.5,6,16,19 In Cuba, vaccination against measles and rubella is not included in the immunization program for HCWs; it is included in the national immunization program with high coverage of the population and no one has been reported with these diseases since more than two decades ago.20

The observed seropositivity rate with less seroprotection in younger HCWs for measles could be considered an unexpected result because of the high vaccine coverage of the population. Nevertheless, several studies have shown similar results.16,18,21,22 Aypak, et al, found that 79.2% of staff aged ≤25 years and more than 90% of older group were immune.16 Urbizondo, et al,22 reported seroprotection in 94.4% of HCWs aged ≤30 years and in 97.0% of older ones. No plausible reason explains the increased seroprotection in physicians compared with other job categories.

Varicella is a highly contagious infectious disease frequent in tropical areas and occurs more commonly in adults than in children. Because varicella vaccine is not included in national immunization schedules in many countries, including Cuba, acquisition of natural immunity against the disease is frequent. This might explain the observed seroprotection in Cuban HCWs.23

Our findings and analysis are limited by the characteristics of HCWs studied. They worked overseas because of specific skills and competence issues that could limit the comparison with a general population of HCWs in Cuba. In addition, recall bias of the participants needs to be considered regarding the previous history of hepatitis B vaccination. Raising awareness of HCWs, improving management and increasing supervision on vaccination programs would help a better assessment of the situation and increase the vaccine coverage.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank the assistance of Mr. Carlos L Crespo Palacios for reviewing this paper.

Conflicts of interest:

None declared.

Cite this article as: Guanche Garcell H, Villanueva Arias A, Guilarte García E, Alfonso Serrano RN. Seroprotection against vaccine-preventable diseases amongst health care workers in a community hospital, Qatar. Int J Occup Environ Med 2016;7:234-240.

References

- 1.Sydnor E, Perl TM. Healthcare providers as sources of vaccine-preventable diseases. Vaccine. 2014;32:4814–22. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.03.097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Maltezou HC, Poland GA. Vaccination policies for healthcare workers in Europe. Vaccine. 2014;32:4876–80. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.10.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Talbot TR. Update on immunization for healthcare personnel in the United States. Vaccine. 2014;32:4869–75. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.10.090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.CDC CDC. Updated CDC recommendations for the management of hepatitis B virus-infected health-care providers and students. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2012;61:1–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Black AP, Vilivong K, Nouanthong P. et al. Serosurveillance of vaccine-preventable diseases and hepatitis C in healthcare workers from Lao PDR. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0123647. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0123647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Flores-Sanchez L, Paredes-Solis S, Balanzar Martinez A. et al. Hepatitis B vaccination coverage and associated factor for vaccine acceptance: a cross-sectional study in health workers of the Acapulco General Hospital, Mexico. Gac Med Mex. 2014;150:395–402. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Topuridze M, Butsashvili M, Kamkamidze G. et al. Barriers to hepatitis B vaccine coverage among healthcare workers in the Republic of Georgia: An international perspective. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2010;31:158–64. doi: 10.1086/649795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Assunção AÁ, Araújo TM, Ribeiro RB, Oliveira SV. [Hepatitis B vaccination and occupation exposure in the healthcare sector in Belo Horizonte, Minas Gerais] Rev Saude Publica. 2012;46:665–73. doi: 10.1590/s0034-89102012005000042. [in Portuguese]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mueller A, Stoetter L, Kalluvya S. et al. Prevalence of hepatitis B virus infection among health care workers in a tertiary hospital in Tanzania. BMC Infectious Diseases. 2015;15:386. doi: 10.1186/s12879-015-1129-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lamberti M, De Rosa A, Garzillo EM. et al. Vaccination against hepatitis b virus: are Italian medical students sufficiently protected after the public vaccination programme? J Med Toxicol. 2015;10:41. doi: 10.1186/s12995-015-0083-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alqahtani JM, Abu-Eshy SA, Mahfouz AA. et al. Seroprevalence of hepatitis B and C virus infections among health students and health care workers in the Najran region, southwestern Saudi Arabia: The need for national guidelines for health students. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:577. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Coppola N, Corvino AR, De Pascalis S. et al. The long-term immunogenicity of recombinant hepatitis B virus (HBV) vaccine: contribution of universal HBV vaccination in Italy. BMC Infectious Diseases. 2015;15:149. doi: 10.1186/s12879-015-0874-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ogoina D, Pondei K, Adetunji B. et al. Prevalence of Hepatitis B Vaccination among Health Care Workers in Nigeria in 2011–12. Int J Occup Environ Med. 2014;5:51–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Byrd KK, Lu P, Murphy TV. Hepatitis B Vaccination Coverage Among Health-Care Personnel in the United States. Public Health Reports. 2013;128:498–509. doi: 10.1177/003335491312800609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sheek Hussein M, Hasmey R, Alsuwaidi AR. et al. Seroprevalence of measles, mumps, rubella, varicella zoster and hepatitis A-C in Emirati medical students. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:1047. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-1047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aypak C, Bayram Y, Eren H. et al. Susceptibility to measles, rubella, mumps and varicella zoster viruses among healthcare workers. J Nippon Med Sch. 2012;79:453–8. doi: 10.1272/jnms.79.453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guanche Garcell H, Fernandez Hernandez TM, Abu Baker Abdo E, Villanueva Arias A. Evaluation of the timeliness and completeness of communicable disease reporting: Surveillance in The Cuban Hospital, Qatar. Qatar Med J. 2014;16:50–6. doi: 10.5339/qmj.2014.9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guanche Garcell H, Villanueva Arias A, Guilaete Garcí E. et al. A successful Stragedy for Improving the Influenza Immunization Rates of Health Care Workers without a Mandatory Policy. Int J Occup Environ Med. 2015;6:184–6. doi: 10.15171/ijoem.2015.595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kumakura S, Shibata H, Onoda K. et al. Seroprevalence survey on measles, mumps, rubella and varicella antibodies in healthcare workers in Japan: sex, age, occupational-related differences and vaccine efficacy. Epidemiol Infect. 2014;142:12–9. doi: 10.1017/S0950268813000393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reed G, Galindo MA. Cuba's National Immunization Program. MEDICC Review. 2007;9:5–7. doi: 10.37757/MR2007V9.N1.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ho TS, Wang SM, Wang LR, Liu CC. Changes in measles seroepidemiology of healthcare workers in southern Taiwan. Epidemiol Infect. 2012;140:426–31. doi: 10.1017/S0950268811000598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Urbiztondo L, Borràs E, Costa J. et al. Working Group for the Study of the Immune Status in Healthcare Workers in Catalonia Prevalence of measles antibodies among health care workers in Catalonia (Spain) in the elimination era. BMC Infect Dis. 2013;13:391. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-13-391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Anuario Estadístico de Salud. Ministerio de Salud pública, Cuba, 2012. Available from www.sld.cu/servicios/estadisticas/. (Accessed March 23, 2012).