ABSTRACT

Background: Organizations assisting refugees are over burdened with the Syrian humanitarian catastrophe and encounter diverse difficulties facing the consequences of this massive displacement. Aid-workers experience the horrors of war through their efforts to alleviate suffering of Syrian refugees.

Objective: This study of Syrian refugee aid-workers in Jordan examined work-stressors identified as secondary traumatic stress (STS), number of refugees assisted, worker feelings towards the organization, and their associations to PTSD-symptoms, wellbeing and intimacy. It also examined whether self-differentiation, physical health, and physical pain were associated with these variables.

Method: Syrian refugee aid-workers (N = 317) in Jordan’s NGOs were surveyed. Univariate statistics and structural equation modeling (SEM) were utilized to test study hypotheses.

Results: Increased STS was associated with lower self-differentiation, decreased physical health and increased physical pain, as well as elevated PTSD-symptoms and decreased intimacy. Decreased connection to the NGO was associated with lower self-differentiation, decreased physical health, increased physical pain, and with decreased intimacy and wellbeing. Lower self-differentiation was associated with increased PTSD-symptoms, decreased wellbeing and intimacy. Elevated physical pain was associated with increased PTSD-symptoms, and decreased wellbeing. Diverse mediation effects of physical health, physical pain and self-differentiation were found among the study’s variables.

Conclusions: Aid-workers who assist refugees were at risk of physical and mental sequelae as well as suffering from degraded self-differentiation, intimacy and wellbeing. Organizations need to develop prevention policies and tailor interventions to better support their aid-workers while operating in such stressful fieldwork.

KEYWORDS: Secondary traumatic stress, physical health and pain, intimacy, wellbeing, PTSD-symptoms, humanitarian work

HIGHLIGHTS: • Aid-workers who assist Syrian refugees are at risk of suffering from deteriorated physical health, pain, and disruptions in psychological regulating mechanism due to experiencing STS, feeling disconnected from the organization and the workload. • Working with traumatized populations encompasses negative impacts on the wellbeing, intimate relationships and the developing of PTSD-symptoms among aid-workers.• It is important of include physical and mental health and organizational factors in interventions and prevention policies to support trauma aid-workers.

Antecedentes: Las organizaciones que ayudan a los refugiados están sobrecargadas con la ayuda humanitaria siria catástrofe y encontrar diversas dificultades que enfrentan las consecuencias de esta masiva. Los trabajadores de ayuda al desplazamiento experimentan los horrores de la guerra a través de sus esfuerzos para alivian el sufrimiento de los refugiados sirios.

Objetivo: Este estudio de trabajadores humanitarios de refugiados sirios en Jordania examinó los estresores laborales identificados como el estrés traumático secundario (STS en sus siglas en inglés), el número de refugiados asistidos, los sentimientos del trabajador con respecto a la organización, y sus asociaciones con los síntomas del TEPT, bienestar e intimidad. Se examinó también si la auto-diferenciación, la salud física, y el dolor físico se asociaban con estas variables.

Método: Se encuestaron los trabajadores humanitarios de refugiados sirios (N=317) de organizaciones no gubernamentales (ONGs) en Jordania. Se utilizaron las estadísticas univariadas y el modelamiento de ecuaciones estructurales (SEM en sus siglas en inglés) para probar las hipótesis del estudio.

Resultados: El aumento en el STS se asoció con una más baja auto-diferenciación, una disminuida salud física y un aumento del dolor físico, como también con síntomas elevados de TEPT y una intimidad disminuida. Una conexión disminuida con la ONG se asoció con una más baja auto-diferenciación, una disminuida salud física, un aumento de dolor físico, y con una disminuida intimidad y bienestar. Una más baja auto-diferenciación se asoció con un aumento en los síntomas del TEPT, y un disminuido bienestar e intimidad. El dolor físico elevado fue asociado con un aumento en los síntomas del TEPT, y un disminuido bienestar. Se encontraron diversos efectos mediadores de la salud física, dolor físico y la auto-diferenciación entre las variables del estudio.

Conclusiones: Los trabajadores humanitarios que asisten a los refugiados se encuentran en riesgo de secuelas físicas y mentales como también de sufrir un deterioro en su auto-diferenciación, intimidad y bienestar. Las organizaciones necesitan desarrollar políticas de prevención y adaptar intervenciones para apoyar mejor a sus trabajadores humanitarios mientras operan en tan estresante campo laboral.

PALABRAS CLAVE: Estrés traumático secundario, salud y dolor físico, intimidad, bienestar, síntomas del TEPT, trabajo humanitario

背景:协助难民的组织承受着叙利亚人道主义灾难的沉重负担,并面临着各种艰巨挑战面临着如此大规模的后果 移位。援助工作者通过减轻叙利亚难民的苦难而经历了战争的恐怖。

目标:本研究针对约旦的叙利亚难民救援人员,考查了被认定为继发性创伤应激(STS)的工作压力源,帮助的难民人数和工作人员对组织的感受,以及这些变量与创伤后应激障碍症状,心身健康状况及亲密关系的关联。同时还考查了自我分化、躯体健康和躯体疼痛是否与这些变量相关。

方法:对317名约旦非政府组织的叙利亚难民救援人员进行了调查。单变量统计和结构方程模型(SEM)用于检验研究的假设。

结果:STS增加与自我分化程度降低,躯体健康状况下降,躯体疼痛加剧,PTSD症状升高和亲密关系减弱有关。与非政府组织的联结减弱与自我分化程度降低,躯体健康状况下降,躯体疼痛加剧以及亲密关系和心身健康状况下降有关。自我分化程度降低与PTSD症状升高,心身健康状况和亲密关系下降有关。躯体疼痛加剧与PTSD症状升高和心身健康状况下降有关。在本研究的变量中发现了躯体健康、躯体疼痛和自我分化不同的中介效应。

结论:难民救援人员具有患上身心问题继发症的风险,并且承担着自我分化程度、亲密关系和心身健康状况降低的痛苦。组织需开发预防政策并定制干预措施,以便在这种高压力的实地工作中更好地支持其救援人员。

关键词: 继发性创伤应激, 躯体健康及痛苦, 亲密关系, 心身健康, 创伤后应激障碍症状, 人道主义工作

1. Introduction

The war in Syria has resulted in millions of traumatized civilians escaping their country in the search of protection and refuge in neighbouring countries. Jordan, with its already challenged infrastructure issues, hosts approximately two million Syrians who mainly reside in urban areas (United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees). Humanitarian organizations in Jordan are over-burdened by this massive displacement. Their staffs are highly stressed in attempting to provide services that will meet the extensive needs of these refugees (Rizkalla & Segal, 2018). This study examined work stressors and their associations with wellbeing, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms and the intimate lives of humanitarian aid-workers who assist Syrian refugees in Jordan’s refugee camps and host-communities. It also considered whether self-differentiation, physical health, and physical pain were associated with these variables.

1.1. Trauma-work stressors and consequences

Assisting refugees who have endured traumatic experiences can be a psychologically hazardous occupation for aid-workers. Humanitarian service professions include occupational stressors that may negatively affect providers’ behaviour, producing stress symptoms similar in nature to the ones suffered by their traumatized clients (Connorton, Perry, Hemenway, & Miller, 2012; Jachens, Houdmont, & Thomas, 2018). Most common is secondary traumatic stress (STS), resembling to PTSD-symptoms that follow frequent exposure to trauma materials including emotional and behavioural responses such as intrusiveness of persistent arousal, avoidance and/or numbing in the presence of trauma reminders, and re-experiencing the survivor’s trauma event (Figley, 1995). Major risk factors for developing STS among providers include less experience, having a personal trauma-history, greater exposure to trauma clients, and higher caseloads (Baird & Jenkins, 2003). These work trauma-exposures and stressors were found to affect aid-workers’ personal, interpersonal, and professional lives (Chemali et al., 2017; Taylor, Gregory, Feder, & Williamson, 2018).

1.2. Trauma and intimacy

The negative association between trauma and survivors’ personal lives is well established. Trauma survivors and their partners report suffering from emotional and sexual intimacy disengagement (Henry et al., 2011). Researchers explain that individuals who suffered from PTSD, experience avoidance and numbness, which inhibit self-disclosure and expression of positive feelings (Dekel & Solomon, 2006). Wives of veterans with PTSD reported decreased marital intimacy after their partners returned from the war (Mikulincer, Florian, & Solomon, 1995), psychological and marital difficulties (Cabrera-Sanchez & Friedlander, 2017; Lambert, Engh, Hasbun, & Holzer, 2012), as well as avoiding dealing with conflictual issues within the relationship (Henry et al., 2011).

Studies of STS and the intimate lives of humanitarian aid-workers report that aid-workers assisting survivors of sexual violence, experienced STS associated with decreased sexual intimacy (Rizkalla, Zeevi-Barkay, & Segal, 2017), and demonstrated changes in trusting others and feeling intimate with significate others (Erez Shtark-Benyamin, 2011; VanDeusen & Way, 2006). In Iran, STS was associated with decreased marital intimacy and sexual satisfaction among nurses (Ariapooran & Raziani, 2019).

1.3. Trauma-work and health

Studies report negative ramifications for aid-workers’ wellbeing including threats to health and somatization (Connorton et al., 2012; Costa et al., 2015; Jachens et al., 2018), especially to the ones working with Syrian refugees (Chemali et al., 2017). They note numerous medical disorders aid-workers experienced while undertaking their humanitarian work, in addition to complaints of physical pain and general fatigue (Costa et al., 2015). Researchers found associations between survivors’ trauma, poor health and somatization, specified in local pain, or unspecified it terms of unexplained medical symptoms (Lahav, Rodin, & Solomon, 2015; Lahav, Stein, & Solomon, 2016). STS symptoms were associated with somatization symptoms among spouses of veterans whom suffered from PTSD in Iran (Kianpoor, Rahmanian, Mojahed, & Amouchie, 2017). Wives of veterans with combat stress reaction suffered from psychiatric and somatic symptoms, six years after their husbands returned from the war (Mikulincer et al., 1995), while wives of former war prisoners reported higher PTSD-symptoms and negative perceived health (Lahav et al., 2016). These studies provide some justification for examining physical health and pain as potential mediating variables in this study analyses.

1.4. Differentiation of the self

Despite the negative consequences for the physical and mental health of aid-workers, researchers have reported that there are personal features that mitigate such risk factors, one of which is differentiation of the self. Self-differentiation is a term stemming from the family systems theory, originally proposed by Murray Bowen (1978). Differentiation is a self-regulating mechanism that is utilized in two interrelated dimensions. The first, on an intra-psychic level, it involves the capacity to balance between intellectual and emotional functioning, especially in highly stressful situations. The second, on an inter-personal level, it involves the capacity to maintain balance between separation and closeness when interacting with significant others. Self-differentiation is postulated to contribute to long-term intimacy and mutuality in close relationships, as well as perseverance during times of struggle. Higher self-differentiation is demonstrated in adaptive functioning and high resilience, even in the face of extreme stress. Whereas lower self-differentiation is manifested in difficulties in balancing conflicting thoughts and emotions, in which a person may become either dependent and pleasing, or emotionally detached and rebellious (Bowen, 1978; Skowron & Friedlander, 1998).

1.5. Differentiation as a regulation mechanism

Self-differentiation was associated with wellbeing, regulating chronic and separation anxieties, enhancing social skills in problem solving and psychological adjustment, as well as reducing stress among couples and enhancing their relational satisfaction (Skowron & Friedlander, 1998; Skowron, Wester, & Azen, 2004). Self-differentiation also mediated the relations between stress and psychological distress (Krycak, Murdock, & Marszalek, 2012; Skowron et al., 2004), as well as the association between PTSD-symptoms and sexual satisfaction (Lahav, Price, Crompton, Laufer, & Solomon, 2019). Self-differentiation was also strongly associated with intimacy in both western and Middle Eastern samples (Patrick, Sells, Giordano, & Tollerud, 2007; Rizkalla & Rahav, 2016), respectively.

1.6. Differentiation and trauma

Studies found association between lower self-differentiation and trauma, as well as STS. Wives of veterans reported low self-differentiation levels associated with their partners’ PTSD severity (Cabrera-Sanchez & Friedlander, 2017), and high distress (Dekel, 2010). Additionally, wives who were indirectly exposed to their husbands’ war captivity reported low self-differentiation and elevated PTSD-symptoms. Self-differentiation mediated the relationship between these variables (Lahav et al., 2016). Adult children of former war-prisoners reported low self-differentiation to mediate the association between exposure to stress and STS-symptoms, forty years after their fathers returned from the war (Zerach, 2015). Furthermore, a mutual association was found over time between self-differentiation and PTSD-symptoms, in which low self-differentiation predicted higher PTSD-symptoms and vice versa (Lahav, Levin, Bensimon, Kanat-Maymon, & Solomon, 2017).

1.7. Differentiation and the workplace

Although many studies examined self-differentiation and its association to first and second-hand trauma survivors, this concept has not received much attention with regard to workplace and organizational stressors. One study with nurses found that higher self-differentiation was associated with lower burnout and greater enthusiasm for the profession (Beebe & Frisch, 2009). However, additional studies that examined workload and organizational stressors and their associations to self-differentiation were not found. In addition, the association between self-differentiation, STS, and PTSD-symptoms among humanitarian aid-workers, as well as studies situating physical health and pain as mediators in similar models were not found either.

Therefore, this study may shed some light on the existing literature and contribute to the field of trauma work in humanitarian settings. It may provide some recommendations to policy makers and organizational stakeholders potentially benefiting humanitarian aid-workers’ wellbeing, especially in the Middle East wherein the mass number of Syrian refugees reside. In this study, number of refugees served, feeling connected to NGO and STS were defined as work stressors.

This study aims at filling some of the gap in the literature by investigating the roles of self-differentiation, physical health and pain, within the associations between the independent variables of number of refugees served, feeling connected to NGO and STS, and the dependent variables of PTSD-symptoms, wellbeing and intimacy among humanitarian aid-workers who provide services to Syrian refugees in Jordan.

Based on the literature review above, we hypothesized the following:

(1) Increased STS, number of refugees served, and decreased feelings of connectedness to NGO will be associated with lower self-differentiation, decreased physical health and increased physical pain. (2) Increased STS and number of refugees served and decreased connection to NGO will be associated with elevated PTSD-symptoms, and decreased intimacy and wellbeing. (3) Lower self-differentiation and physical health, and elevated physical pain will be associated with increased PTSD-symptoms, and decreased intimacy and wellbeing. (4) Self-differentiation, physical health and physical pain may potentially mediate some of the associations between the study’s variables.

2. Method

2.1. Participants

Humanitarian aid-workers (N = 317), including employees and volunteers from the medical, mental health, management and service sectors, working in fifteen of Jordan’s NGOs comprised the sample of the study. The participating organizations were international, national and local (See Table 1 for numbers of aid-workers recruited from each organization).

Table 1.

Aid-workers participants according to NOGs distribution (N = 317).

| International organizations |

National organizations |

Local charity organizations |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | |||

| Japan Emergency NGO | 73 (23.3%) | Jordan Health Aid Society | 87 (27.4%) | Waqea | 9 (2.8%) |

| Save the Children | 20 (6.3%) | Noor Al Hussein Foundation | 41 (12.8%) | Dar Alkarama | 8 (2.4%) |

| International Medical Corps | 19 (5.9%) | The Jordanian Women’s Union | 19 (5.9%) | Green Crescent | 7 (2.1%) |

| Center for Victims of Torture | 10 (3.1%) | Bader Centre | 5 (1.7%) | ||

| Mercy Corps | 8 (2.4%) | Naher El Rahmeh | 5 (1.7%) | ||

| International Orthodox Christian Charities | 4 (1.4%) | ||||

| UN Women | 2 (0.7%) | ||||

| Total number of participants N = 317 (100%) | 136 (42.8%) | 147 (46.1%) | 34 (10.7%) | ||

2.2. Procedure and data collection

The researchers gained approval from the organizations to disseminate the survey among aid-workers during their working hours. Explanation of the purpose and procedures of the study were provided during the organizations’ weekly meetings. The right to withdraw or refuse participation was also offered to aid-workers prior to their participation. Data collection took place from March to August 2014 and in May 2015. The majority of the surveys were in Arabic (96%) for local aid-workers and in English (4%) for internationals. The translation of the scale examining STS was conducted with blind back-translation to English by two independent professionals. Five aid-workers assisted in adjusting the translation according to the context of their work in Jordan, so that it would not compromise the Scale’s validity. All other scales were previously used in the Arabic version among Palestinian couples and Syrian refugee samples (Krycak et al., 2012; Rizkalla & Segal, 2019). Participation was anonymous, voluntary and did not include incentives. Each completed survey was required to be sealed in an envelope and directly delivered to the researchers. A consent form was included with the survey with no signature requirement in order to ensure authentic responses and a safe space for participation without imposing job risk. Aid-workers response rate was 70%. Refusal to participate was manifested in empty surveys sealed in the envelopes and delivered to the researchers. The study was approved by the Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects (University of California, Berkeley (CPHS, February 2014)). Inclusion criteria were: (1) Being a humanitarian aid-worker, (2) Working at an organization in Jordan, (3) Delivering services to Syrian refugees in camps, host communities, or both, and (4) Being 19 years of age and above.

2.3. Measures

Data gathering included socio-demographic information, i.e. age, sex, marital status, national origin, profession, years of marriage, number of children, education, years of experience, income, as well as information on health and somatic complaints.

Work stressors were measured by three indicators (the first two created for this study):

Number of refugees served (1 item), measured by the average number of refugees with whom the aid-workers talked every week during their work.

Feelings of connectedness to the organization, ranging from 1 = very high to 5 = very low.

Secondary Trauma Questionnaire (STQ) (Motta, Kefer, Hertz, & Hafeez, 1999) scores utilized to assess STS. The scale includes 20 Likert-type items ranging from 1 = rarely/never to 5 = very often. Some of the items are ‘I experience intrusive, unwanted thoughts about refugees’ problems,’ and ‘I have wished that I could avoid dealing with refugees.’ Higher scores on the scale indicate increasing STS as experienced in PTSD similar symptomology: re-experiencing, avoidance, and increased arousal. The scale is based on the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV) (American Psychiatric Association [APA], 1994) for PTSD criteria and The Compassion Fatigue Self-Test for Psychotherapists (Figley, 1995). The current sample’s Cronbach’s α = .95.

Potential mediators by three indicators (the first two created for this study):

Physical health: ‘How would you describe your physical health?’ (Coded: 1 = good, 2 = fair, and 3 = poor).

Physical pain: ‘Do you currently experience physical pain or discomfort?’ (Coded: 0 = no, 1 = yes).

The Differentiation of Self Inventory-Revised (DSI-R) (Skowron & Schmitt, 2003), includes 46 items that examine the two dimensions of self-differentiation. First the intra-psychic dimension features of emotional reactivity (e.g. ‘people have remarked that I’m overly emotional’) and I position (e.g. ‘I usually do not change my behavior simply to please another person’). Second, the inter-personal dimension features of emotional cut-off (e.g. ‘I’m often uncomfortable when people get too close to me’) and fusion with others (e.g. ‘I worry about people close to me getting sick, hurt, or upset’). Higher scores indicate greater self-differentiation. The Arabic version of the scale was previously used among Palestinian participants (Rizkalla & Rahav, 2016). The current sample’s Cronbach’s α = .81.

Study outcomes were measured by three indicators (the first item created for this study):

Wellbeing: ‘In general, how would you describe your emotional wellbeing?’ (Coded: 1 = good, 2 = fair, and 3 = poor).

The Harvard Trauma Questionnaire (HTQ) (Mollica et al., 1992), a 16 item Likert-type scale that measures PTSD-symptom severity ranging from 1 = not at all to 4 = extremely. Participants were asked to indicate how much various symptoms bothered them in the last week due to experiencing trauma events, such as ‘feeling as though the event is happening again,’ ‘having less interest in daily activities,’ and ‘avoiding activities that remind you of the traumatic or hurtful event.’ Higher scores indicate increasing PTSD severity. The Arabic version of the scale was previously utilized with Syrian refugees in Jordan (Rizkalla & Segal, 2018). The current sample’s Cronbach’s α = .95.

Personal Assessment of Intimacy in Relationships (PAIR) (Schaefer & Olson, 1981) is a 40 item Likert-type scale ranging from 0 = strongly disagree to 4 = strongly agree. The scale examines the perception of intimacy as aid-workers currently experience it with their partners or with the last partner they had (regardless of their marital status), such as ‘my partner listens to me when I need someone to talk to’ and ‘we have few friends in common.’ The original scale contains 36 items, 30 items examine the five types of intimacy (emotional, social, intellectual, sexual and recreational), and six items examine social desirability, which were excluded from the analyses. Additional 4 items of anger management in a relationship were included from the Intimate Relationship Scale (Hershaleg, 1984). The Arabic translated scale was previously utilized with Syrian refugees in Jordan (Rizkalla & Segal, 2019). Higher scores indicate greater intimacy in the relationship. The current sample’s Cronbach’s α = .78.

2.4. Data analysis

Univariate descriptive statistics, correlations, Alpha reliabilities and substitution of missing data were conducted for the majority of scales utilizing SPSS version 25. Structural equation modeling (SEM) analysis using AMOS version 25 was performed to examine the model fit of the data, as well as bootstrap analyses that included 2000 bootstrap resamples with 95% confidence intervals to examine the direct path estimates between the variables. Since the analyses included three mediators, the specific indirect effects were calculated using Monte Carlo method for assessing mediation (Selig & Preacher, 2008) and the Sobel test (Preacher & Hayes, 2008). Missing data were handled using MVA Maximum likelihood substitution. Missing data among the study’s variables ranged from 3.1% to 26.5%. The results of Little’s MCAR test, indicated that the data were completely missing at random (Collins, Schafer, & Kam, 2001), χ2 = 34,901.73; df = 104,157; p = 1.000.

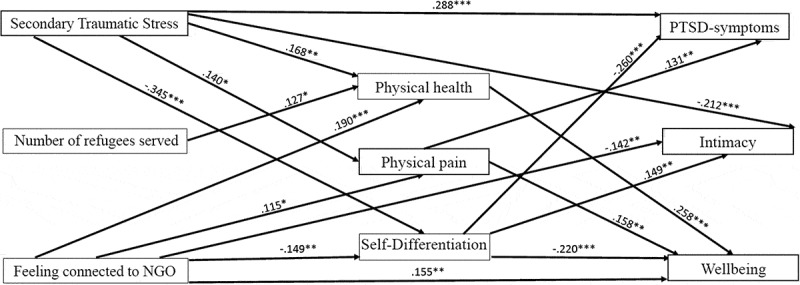

The model contained three endogenous outcomes of PTSD-symptomology, intimacy in relationships and wellbeing of aid-workers as potentially mediated by self-differentiation, physical health and pain. Potential exogenous variables of work stressors were STS, number of refugees served, and feeling connected to NGO (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

SEM model assessing the relation between STS, number of refugees served, feeling connected to NGO, physical health, physical pain, and self-differentiation in predicting PTSD-symptoms, intimacy and wellbeing of aid-workers. Note. Solid lines represent significant predictions, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.0001.

Dashed lines representing non-significant predictions and curved lines representing covariates between constructs were omitted for clarity. The associations STS→ wellbeing, number of refugees served → PTSD-symptoms, and number of refugees served → wellbeing were omitted from the model to gain a better model fit.

3. Results

3.1. Demographics and work related variables

The sample was comprised of 317 NGO aid-workers in Jordan who provided services in refugee camps, host communities, or both. The location of the work varied: refugee camps (64%), Amman (17%), Irbid (9%), Ar Ramtha (7%), Mafraq (1.5%), and Jeresh (1.5%). Aid-workers’ demographics and work related experiences are presented in Table 2. Participants were 56.8% women (n = 180) and 43.2% men (n = 137); their age ranged from 19 to 68 years (M = 29.32, SD = 7.91). The majority of participants were of Jordanian nationality (91%), while 8% were Syrians, and 1% others; 10.7% reported being a refugee in the past, and 9.1% were currently living in refugee camps, 60.7% in Palestinian refugee camps, and 39.3% in Syrian refugee camps. Aid-workers also reported on their relationship with their organizations, as provided in Table 2.

Table 2.

Aid-workers demographics, work experience, and relationship with their organizations.

| Demographics | Range | M | SD | N | Percent | - | - | - |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex: Male | 137 | 43.2 | - | - | - | |||

| Female | 180 | 56.8 | - | - | - | |||

| Age | 19–68 | 29.32 | 7.91 | - | - | - | - | - |

| Years of education | 4–26 | 15.83 | 2.37 | - | - | - | - | - |

| Income: High | 21 | 6.5 | - | - | - | |||

| Medium | 204 | 64.5 | - | - | - | |||

| Low | 92 | 29.0 | - | - | - | |||

| Marital Status: Single | 166 | 52.4 | - | - | - | |||

| Married | 144 | 45.3 | - | - | - | |||

| Separated/Divorced | 7 | 2.3 | - | - | - | |||

| Years of marriage | 0–49 | 3.68 | 7.24 | - | - | - | - | - |

| Number of children | 0–13 | 0.97 | 1.84 | - | - | - | - | - |

| Religion: Muslim | 302 | 95.2 | - | - | - | |||

| Christian | 11 | 3.5 | - | - | - | |||

| Druze | 3 | 1.0 | - | - | - | |||

| Other | 1 | 0.3 | - | - | - | |||

| Work Experience | - | - | - | |||||

| Employment: Worked full time | 268 | 84.7 | - | - | - | |||

| Part time | 25 | 7.8 | - | - | - | |||

| Volunteered | 24 | 7.5 | - | - | - | |||

| Years of experience | 0–45 | 3.09 | 5.54 | - | - | - | - | - |

| Number of refugees served per average week | 1–5000 | 424.77 | 633.56 | - | - | - | - | - |

| Hours worked each week | 1–100 | 35.79 | 15.72 | - | - | - | - | - |

| Hours of inquiries each week | 1–70 | 27.35 | 16.06 | - | - | - | - | - |

| Agency Relationship Evaluations (Responses in Likert Format): | Very high | High | Moderate | Low | Very low | |||

| Feeling connected to the NGO | 1–5 | 2.19 | .887 | 24.0% | 40.3% | 29.3% | 5.7% | 0.6% |

| Believing in the NGOs ideologies | 1–5 | 2.12 | .878 | 26.5% | 40.9% | 28% | 3.2% | 1.3% |

| The extent of satisfaction from what they do at work | 1–5 | 2.51 | .898 | 13.6% | 33.4% | 43.7% | 6.6% | 2.2% |

| The extent of helping others at work make them continue doing it | 1–4 | 1.98 | .839 | 31.9% | 42.2% | 21.7% | 4.1% | 0% |

Number of refugees served on average per week includes speaking to refugees, distribution of food and other items, especially that 64% of aid-workers worked in refugee camps, wherein high volume of encounters with refugees occur.

Aid-workers reported their physical health was good (68.8%), fair (28.4%), and poor (2.8%); 34.4% reported currently suffering from physical pain, 16.7% reported having a medical condition, and 3.8% consumed pain-killers regularly. Somatic complains included abdominal pain (3.2%), back pain (1.6%), joint pain (1.6%), headaches (1.6%), allergies (1.6%), fatigue and lack of sleep (1.3%), and other unspecified pain (4.7%). Their emotional wellbeing was good (43.8%), fair (46.7%), and poor (9.5%).

Intimacy in relationships experienced by aid-workers ranged from 0.50 to 4 (M = 2.22, SD = 0.43), while self-differentiation ranged from 2.24 to 5.35 (M = 3.77, SD = 0.52); 13% of aid-workers suffered from PTSD-symptoms due to traumatic events and 46% screened positive on STS.

3.2. Associations between the study variables

Descriptive statistics and correlations between variables in the study are included in Table 3. All correlations were in the low-moderate range, however the strongest associations occurred between STS and PTSD-symptoms, physical health and pain; self-differentiation and PTSD-symptoms; physical health and wellbeing; and STS and intimacy. Number of refugees served was only associated with physical health and pain. Initially, the variable ‘years of experience’ was included in the analysis and yielded no significant correlations with any of the study’s variables. Demographic variables such as sex and marital status were moderately correlated with only one variable, and therefore they were not included either in the final path model.

Table 3.

Intercorrelations between the main study measures (N = 317).

| Variables | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. STS | 2.13 | .845 | - | ||||||||

| 2. Number of refugees | 423.77 | 633.562 | .094 | - | |||||||

| 3. Connected to NGO | 2.19 | .887 | .076 | −.011 | - | ||||||

| 4. DIS-R | 3.77 | .523 | −.364** | −.061 | −.175** | - | |||||

| 5. Physical health | 1.34 | .531 | .188** | .138* | .201** | −.176** | - | ||||

| 6. Physical pain | .34 | .476 | .160** | .111* | .124* | −.116* | .399** | - | |||

| 7. PTSD-symptoms | 1.66 | .679 | .418** | .080 | .145** | −.389** | .151** | .214** | - | ||

| 8. Intimacy | 2.22 | .430 | −.313** | −.096 | −.212** | .278** | −.226** | −.191** | −.289** | - | |

| 9. Wellbeing |

1.66 | .645 | .130* | .074 | .263** | −.309** | .389** | .304** | .282** | −.216** | - |

STS = secondary traumatic stress; DIS-R = differentiation of the self. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01. Note. Connected to NGO, 1 = very high to 5 = very low. Physical health, 1. Good, 2. Fair, 3. Poor. Physical pain, 0 = no, 1 = yes. Wellbeing, 1. Good, 2. Fair, 3. Poor.

3.3. The research model

Path Analysis fit indices indicated that the theoretical model was a good representation of the data, χ2(9) = 15.39, p = .081, CFI = .983, NFI = .962, TLI = .931, RMSEA = .047 (Figure 1). The model explained 25.3% of PTSD-symptoms variance, 24.7% of wellbeing variance, and 17.6% of intimacy variance.

3.4. Hypotheses and findings

Hypothesis 1. Increased STS, number of refugees served, and decreased feelings of connectedness to NGO will be associated with lower self-differentiation, decreased physical health and increased physical pain.

The first hypothesis was partially confirmed. Increased STS was associated with lower self-differentiation (ß = −.345, p < .001), decreased physical health (ß = .168, p < .002) and increased physical pain (ß = .140, p < .011). Decreased feelings of connectedness to NGO was associated with low self-differentiation (ß = −.149, p < .004), decreased physical health (ß = .190, p < .001) and increased physical pain (ß = .115, p < .037). However increased number of refugees served was only associated with decreased physical health (ß = .127, p < .019). Other associations related to number of refugees served were not significant.

Hypothesis 2. Increased STS and number of refugees served and decreased connectedness to NGO will be associated with elevated PTSD-symptoms, and decreased intimacy and wellbeing.

The second hypothesis was partially confirmed. Increased STS was strongly associated with elevated PTSD-symptoms (ß = .288, p < .001), and decreased intimacy (ß = −.212, p < .001). Decreased connection to NGO was associated with decreased intimacy (ß = −.142, p < .007) and decreased wellbeing (ß = .155, p < .002). Association between feeling connected to NGO and PTSD-symptoms was not significant. Number of refugees served was not associated with any of the endogenous variables.

Hypothesis 3. Lower scores of self-differentiation and physical health, and elevated physical pain will be associated with increased PTSD-symptoms, and decreased intimacy and wellbeing.

The third hypothesis was partially confirmed. Lower self-differentiation was associated with increased PTSD-symptoms (ß = −.260, p < .001), decreased wellbeing (ß = −.220, p < .001) and decreased intimacy (ß = .149, p < .007). Elevated physical pain was associated with increased PTSD-symptoms (ß = .131, p < .008), and decreased wellbeing (ß = .158, p < .003). Association between physical pain and intimacy was not significant. Decreased physical health was only associated with decreased wellbeing (ß = .258, p < .001).

Hypothesis 4. Self-differentiation, physical health and physical pain may potentially mediate some of the associations between the study’s variables.

To examine the mediation effects of the model, bootstrapping analyses for the direct effects and Monte Carlo analyses for the specific indirect effects were conducted, resulting in a complex picture of the findings (Table 4). Physical health fully mediated the association between STS and wellbeing, and partially mediated the association between feeling connected to NGO and wellbeing. Physical pain fully mediated the association between STS and wellbeing, and partially mediated the association between STS and PTSD-symptoms. In addition, physical pain fully mediated the association between feeling connected to NGO and PTSD-symptoms, and partially mediated the association between feeling connected to NGO and wellbeing. Furthermore, self-differentiation fully mediated the association between STS and wellbeing, and partially mediated the association between STS and PTSD-symptoms, as well as partially mediated the association between STS and intimacy. Self-differentiation also fully mediated the association between feeling connected to NGO and PTSD-symptoms, and partially mediated the associations between feeling connected to NGO and intimacy, and feeling connected to NGO and wellbeing. It seems that self-differentiation had the strongest mediation effects among the study’s variables.

Table 4.

Unstandardized regression coefficients, standard errors, and bootstrap 95% confidence intervals for predicting PTSD-symptoms, intimacy and wellbeing through physical health, physical pain, and differentiation.

| Measure | PTSD-symptoms | β (SE) | Intimacy | β (SE) | Wellbeing | β (SE) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) Direct STS | [0.164, 0.399]*** | 0.231 (0.042) | [−0.377, −0.049]** | −0.108 (0.028) | [0.000, 0.000] | – |

| Indirect STS through physical health | – | – | [−0.021, 0.002] | −1.426 (0.005) | [0.011, 0.061]* | 2.597 (0.013) |

| Indirect STS through physical pain | [0.002, 0.034]* | 1.831 (0.008) | [−0.017, 0.002] | −1.248 (0.005) | [0.002, 0.037]* | 1.931 (0.009) |

| Indirect STS through differentiation | [0.039, 0.110]* | 3.975 (0.018) | [−0.048, −0.007]* | −2.464 (0.010) | [0.029, 0.091]* | 3.686 (0.016) |

| (2) Direct number of refugees served | [0.000, 0.000] | – | [−0.125, 0.030] | 0.000 (0.000) | [0.000, 0.000] | – |

| Indirect number of refugees served through physical health | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Indirect number of refugees served through physical pain | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Indirect number of refugees served through differentiation | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| (3) Direct feeling connected to organization | [−0.038, 0.157] | 0.047 (0.038) | [−0.235, −0.046]** | −0.069 (0.026) | [0.044, 0.277]** | 0.112 (0.037) |

| Indirect feeling connected to NGO through physical health | – | – | [−0.022, 0.002] | −1.466 (0.006) | [0.014, 0.063]* | 2.861 (0.012) |

| Indirect feeling connected to NGO through physical pain | [0.000, 0.029]* | 1.626 (0.007) | [−0.014, 0.002] | −1.177 (0.004) | [0.000, 0.032]* | 1.694 (0.008) |

| Indirect feeling connected to NGO through differentiation | [0.008, 0.056]* | 2.463 (0.012) | [−0.024, −0.002]* | −1.938 (0.005) | [0.006, 0.046]* | 2.389 (0.010) |

STS – > wellbeing, number of refugees served –> PTSD-symptoms, number of refugees served –> wellbeing, and physical health–> PTSD-symptoms were omitted from the model to gain a better model fit.

*p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p = 0.001

4. Discussion

This study adds some evidence to the literature on work-stressors potential effects on aid-workers’ physical and mental health, their personal lives, and their ability to regulate their thoughts and feelings in such demanding settings (see Figure 1). STS was associated with decreased self-differentiation, intimacy, physical health, and increased PTSD-symptoms and pain. Decreased self-differentiation was associated with deteriorated PTSD-symptoms, wellbeing and intimacy, which suggests that self-differentiation is a resilience indicator for refugee aid-workers. Decreased feeling of connectedness to NGO was associated with decreased health, wellbeing, self-differentiation and intimacy, and increased pain, which suggests that organizational factors may play a protective factor for aid-workers. Increased number of refugees served was only associated with decreased health, and did not contribute to the model’s mediation effects. Several mediation effects were observed. Self-differentiation mediated the associations between STS and NGO connectedness with all the study’s outcomes, whereas physical health and pain mediated the associations between STS and feeling connected to NGO and wellbeing. Additionally, physical pain mediated the associations between STS and feeling connected to NGO and PTSD-symptoms. These study findings showed variable support though little contradiction in the literature.

4.1. STS and its negative associations

The link between STS and PTSD-symptoms among aid-workers is understudied. Associations between STS, trauma exposure, anxiety and depression (Colombo, Emanuel, & Zito, 2019; Gärtner, Behnke, Conrad, Kolassa, & Rojas, 2019) with an additional association to PTSD-symptoms and work stressors (Griffiths, Royse, & Walker, 2018) have been observed. Trauma exposure has been associated with pain and physical health problems (D’Andrea, Sharma, Zelechoski, & Spinazzola, 2011; Pérez, Abrams, López-Martínez, & Asmundson, 2012). STS and exposure to trauma clients has been associated with fatigue, insomnia, joint/muscular pain, gastritis, headaches, and respiratory difficulties (Colombo et al., 2019). STS mediated the associations between exposure to trauma and perceived physical health (Lee, Gottfried, & Bride, 2018). The association between trauma exposure and physical health was also mediated by hyperarousal and depressive symptoms (Pérez et al., 2012).

STS was also associated to decreased intimacy among therapists (Bober & Regehr, 2006), and decreased sexual intimacy among sexual survivors’ aid-workers (Rizkalla et al., 2017). Therapists addressing sexual violence experienced changes in feeling related to their intimate partners (Erez Shtark-Benyamin, 2011; VanDeusen & Way, 2006). Helpline workers were hindered from starting relationships, and had difficulties enjoying sexual relationships with partners (Taylor et al., 2018). Nurses with higher STS experienced decreased sexual satisfaction and intimacy (Ariapooran & Raziani, 2019). These studies seem to support our findings on the negative impacts of STS on aid-workers’ PTSD-symptoms, physical health, pain, and intimate lives.

4.2. Self-differentiation as a protective factor

Self-differentiation, thought to be a stable feature, which could be changed through intervention (Bowen, 1978), enhanced with increased intimacy (Rizkalla & Rahav, 2016), and undermined by trauma exposure (Dekel, 2010; Lahav et al., 2017), PTSD-symptoms (Lahav et al., 2019, 2016), and poor wellbeing (Jankowski & Sandage, 2012; Skowron & Friedlander, 1998). Self-differentiation’s role as a protective factor in this study’s findings, a mediator between positive and negative outcomes, was supported in the literature with findings of its mediation of the associations between stress exposure and STS-symptoms (Zerach, 2015) and wellbeing (Jankowski & Sandage, 2012), perceived psychological distress (Krycak et al., 2012) and indirect exposure to war captivity and perceived health (Lahav et al., 2016). A better self-regulating mechanism not only contributed to the capacity for affect regulation, but also to interpersonal balance of closeness and distance, which in turn enhanced intimacy in close relationships (Ariapooran & Raziani, 2019; Patrick et al., 2007; Rizkalla & Rahav, 2016). Low self-differentiation mediated the association between PTSD-symptoms and sexual satisfaction among spouses of former war prisoners (Lahav et al., 2019). Perhaps aid-workers with STS tried to distance themselves and regulate their overwhelmed feelings of refugee work. In doing so they may have also distanced themselves from their beloved ones, which in turn contributed to their decreased intimacy (Ariapooran & Raziani, 2019).

4.3. Feeling connected to NGO as a protective factor

Study findings related to the positive effects of connectedness to the NGO receive considerable support in the literature on positive outcomes associated with organizational efforts to improve worker conditions. Researchers suggested that improving providers’ role competence and self-efficacy may promote coping strategies and resilience in response to trauma work (Benight & Bandura, 2004; Ben-Porat, 2017). Organizational support, especially from managers had significantly contributed to social workers’ sense of role competence in dealing with job stressors and enhanced their feelings of relatedness to their work (Taylor et al., 2018). Organizational efforts to prioritize providers’ self-care was suggested as beneficial to their effectiveness and wellbeing (Lee et al., 2018; Taylor et al., 2018). Positive organizational culture, clear guidelines, upheld values, and organizational support contributed to refugees and asylum seekers counsellors’ wellbeing (Roberts, Ong, & Raftery, 2018). Low levels of social support, meaning of work, leadership quality, and sense of community predicted poor wellbeing of employees in 34 European countries (Schütte et al., 2014). Work stressors and disrupted beliefs affected providers’ intimate relationships (Griffiths et al., 2018), and engagement in leisure activities as a self-care strategy (Bober & Regehr, 2006). Considering these findings, one may consider feeling connected to NGO as a protective organizational factor against poor physical health, pain, wellbeing and intimacy. Future studies needs to explore further the contribution of work stressors to unhealthy behaviours and intimate lives.

Studies on the impacts of feeling connected to NGO and self-differentiation are scarce. Perhaps when aid-workers receive organizational support, believe in the organization’s vision and goals, and perceive NGO services as helpful, it enhances their sense of significance in working at the organization and in the humanitarian sector in general, and consequently help them better regulate their thoughts and intense feelings during trauma work.

4.4. Physical health and pain as mediators

There is broad recognition of the role of physical health and pain as mediators of psychosocial experience. STS’s negative association with health also received support (Chemali et al., 2017; Gärtner et al., 2019). For example, cemetery workers’ constant contact with the deceased often internalize others’ pain, resulting in suffering from similar health and pain symptoms (Colombo et al., 2019). Mindfulness, meditation and yoga reduced aid-workers perceived stress and back pain, and raised their physical awareness, wellbeing and coping strategies (Chemali et al., 2017; Eriksen & Ditrich, 2015; Hartfiel et al., 2012). Yoga-based stress management (YBSM) was especially effective to frontline providers’ physical and mental health, and decreased their STS (Riley et al., 2017). Perhaps verbal traditional interventions are not useful to aid-workers (Rizkalla et al., 2017) due to their focus only on the emotional aspects of trauma work, rather than holistic interventions that also address the physical aspects with practical stress reduction techniques.

Finally the number of refugees served was only associated with decreased health, this being concordant with other studies on high caseload (Costa et al., 2015; Griffiths et al., 2018; Riley et al., 2017). Perhaps in the Middle East, where mental health interventions are stigmatized (Rohlof, Knipscheer, & Kleber, 2014), somatic complains and poor health are more acceptable and even justified when working with high volume of traumatized populations.

The study’s findings draw attention to the importance of tailoring interventions that assist aid-workers in differentiating themselves from refugees, to better regulate their thoughts and emotions and consequently better cope with their PTSD-symptoms, intimate relationships and poor wellbeing. Organizations need to develop prevention policies and strategies to make their aid-workers feel more connected to their role at work, and the goals and vision of the organization, which eventually may benefit their wellbeing and health. Organizational policy makers need to realize that it is their responsibility to better equip aid-workers with the support needed to mitigate negative ramifications of trauma work on the physical and mental health, as well as the intimate relationships of aid-workers. Organizational support interventions are recommended to incorporate physical health as well as mental health strategies for aid-workers, since it is crucial, as an organizational pledge, to care for the caregivers to enhance their capacities in caring for the traumatized in humanitarian emergencies.

4.5. Limitations

This study is cross-sectional, and focused on humanitarian aid-workers who provide services to Syrian refugees in Jordan and therefore the generalization to global settings is limited. This study did not assess the physical and mental health of aid-worker prior to starting their work with refugees. Future studies need to consider longitudinal data to better trace changes that may evolve over time when examining the development of stress-related symptoms. Future studies may consider including partners of aid-workers in examining the effects of work-stressors on their physical and mental health. Despite these limitations, the study expands our understanding in providing a holistic prospective of the impact of work stressors, organizational factors, physical health, pain, and self-differentiation, on the mental health, intimate lives and well-being of aid-workers. To our knowledge, no other studies have examined all these variables in the context of the current refugee crisis in the Middle East or elsewhere. To conclude, aid-workers who assist the traumatized are at risk of physical and mental health sequelae as well as suffering from degradation in their regulating mechanisms, intimate relationships and general wellbeing.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by the Mack Center on Mental Health and Social Conflict [Grant SEGAL] and University of California Berkeley.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all humanitarian organizations in Jordan, and their directors who generously collaborated with the researchers, but we will forever be grateful to all humanitarian aid-workers who agreed to participate in this study and provided a glance to their personal and professional lives during serving refugees. We would also like to thank Jamal Atamneh for his assistance in connecting the researchers with NGOs in Jordan; Ramy Al Asheq for his assistance in connecting the researchers with NGOs led by professional Syrians. In addition, we thank Dr. Hanan Bishara for her generous, professional, and dedicated help on her final edits of the translation of the survey in Arabic.

Contributors

Rizkalla was responsible for the design, data collection and management of the project, in addition to data analysis and article preparation. Segal was responsible to the accompaniment of the project, funding resources, and article preparation. All authors have approved the final manuscript for submission and took major role in preparing it.

Disclosure statement

The views expressed in the manuscript are the authors own opinions, and not an official position of the institution or funder that supported this study. No conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Ethics approval

This study was approved by the Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects, University of California, Berkeley (CPHS, February 2014).

References

- American Psychiatric Association (APA) (1994). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (4th ed.). Washington DC: American Psychiatric Association. [Google Scholar]

- Ariapooran S., & Raziani S. (2019). Sexual satisfaction, marital intimacy, and depression in married Iranian nurses with and without symptoms of secondary traumatic stress. Psychological Reports, 122(3), 809–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baird S., & Jenkins S. R. (2003). Vicarious traumatization, secondary traumatic stress, and burnout in sexual assault and domestic violence agency staff. Violence & Victims, 18(1), 71–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beebe R., & Frisch N. (2009). Development of the Differentiation of Self and Role Inventory for Nurses (DSRI-RN): A tool to measure internal dimensions of workplace stress. Nursing Outlook, 57(5), 240–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benight C. C., & Bandura A. (2004). Social cognitive theory of posttraumatic recovery: The role of perceived self-efficacy. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 42(10), 1129–1148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Porat A. (2017). Competence of trauma social workers: The relationship between field of practice and secondary traumatization, personal and environmental variables. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 32(8), 1291–1309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bober T., & Regehr C. (2006). Strategies for reducing secondary or vicarious trauma: Do they work? Brief Treatment and Crisis Intervention, 6(1), 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Bowen M. (1978). Family therapy in clinical practice. New York, NY: Jason Aronson. [Google Scholar]

- Cabrera-Sanchez P., & Friedlander M. L. (2017). Optimism, self-differentiation, and perceived posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms: Predictors of satisfaction in female military partners. Couple and Family Psychology: Research and Practice, 6(4), 235–246. [Google Scholar]

- Chemali Z., Borba C. P. C., Johnson K., Hock R. S., Parnarouskis L., Henderson D. C., & Fricchione G. L. (2017). Humanitarian space and well-being: Effectiveness of training on a psychosocial intervention for host community-refugee interaction. Medicine, Conflict and Survival, 33(2), 141–161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins L. M., Schafer J. L., & Kam C.-M. (2001). A comparison of inclusive and restrictive strategies in modern missing data procedures. Psychological Methods, 6(4), 330–351. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colombo L., Emanuel F., & Zito M. (2019, March). Secondary traumatic stress: Relationship with symptoms, exhaustion, and emotions among cemetery workers. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connorton E., Perry M. J., Hemenway D., & Miller M. (2012). Humanitarian relief workers and trauma-related mental illness. Epidemiologic Reviews, 34(1), 145–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa M., Oberholzer-Riss M., Hatz C., Steffen R., Puhan M., & Schlagenhauf P. (2015). Pre-travel health advice guidelines for humanitarian workers: A systematic review. Travel Medicine and Infectious Disease, 13(6), 449–465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Andrea W., Sharma R., Zelechoski A. D., & Spinazzola J. (2011). Physical health problems after single trauma exposure: When stress takes root in the body. Journal of the American Psychiatric Nurses Association, 17(6), 378–392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dekel R. (2010). Couple forgiveness, self-differentiation and secondary traumatization among wives of former pows. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 27(7), 924–937. [Google Scholar]

- Dekel R., & Solomon Z. (2006). Secondary traumatization among wives of Israeli POWs: The role of POWs’ distress. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 41(1), 27–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erez Shtark-Benyamin K. (2011). The relations between treatment of sexual violence victims, level of empathy and the therapist’s sexual attitudes. Israel: Tel-Aviv University. [Google Scholar]

- Eriksen C., & Ditrich T. (2015). The relevance of mindfulness practice for trauma-exposed disaster researchers. Emotion, Space and Society, 17, 63–69. [Google Scholar]

- Figley C. R. (1995). Compassion fatigue as secondary traumatic stress disorder: An overview In Figley C. R. (Ed.), Compassion fatigue: Coping with secondary traumatic stress disorder in those who treat the traumatized (pp. 1–20). New York, NY: Brunner/Mazel. [Google Scholar]

- Gärtner A., Behnke A., Conrad D., Kolassa I. T., & Rojas R. (2019, January). Emotion regulation in rescue workers: Differential relationship with perceived work-related stress and stress-related symptoms. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths A., Royse D., & Walker R. (2018, May). Stress among child protective service workers: Self-reported health consequences. Children and Youth Services Review, 90, 46–53. [Google Scholar]

- Hartfiel N., Burton C., Rycroft-Malone J., Clarke G., Havenhand J., Khalsa S. B., & Edwards R. T. (2012). Yoga for reducing perceived stress and back pain at work. Occupational Medicine, 62(8), 606–612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henry S. B., Smith D. B., Archuleta K. L., Sanders-Hahs E., Goff B. S. N., Reisbig A. M. J., … Scheer T. (2011). Trauma and couples: Mechanisms in dyadic functioning. Journal of Marital & Family Therapy, 37(3), 319–332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hershaleg A. (1984). Intimacy and mutual familiarity of emotions among married couples in the city and Kibbutz. Israel: Haifa University. [Google Scholar]

- Jachens L., Houdmont J., & Thomas R. (2018). Work-related stress in a humanitarian context: A qualitative investigation. Disasters, 42, 619–634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jankowski P. J., & Sandage S. J. (2012). Spiritual dwelling and well-being: The mediating role of differentiation of self in a sample of distressed adults. Mental Health, Religion & Culture, 15(4), 417–434. [Google Scholar]

- Kianpoor M., Rahmanian P., Mojahed A., & Amouchie R. (2017). Secondary traumatic stress, dissociative and somatization symptoms in spouses of veterans with PTSD in Zahedan, Iran. Electronic Physician, 9(4), 4202–4206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krycak R. C., Murdock N. L., & Marszalek J. M. (2012). Differentiation of self, stress, and emotional support as predictors of psychological distress. Contemporary Family Therapy, 34(4), 495–515. [Google Scholar]

- Lahav Y., Levin Y., Bensimon M., Kanat-Maymon Y., & Solomon Z. (2017). Secondary traumatization and differentiation among the wives of former POWs: A reciprocal association. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 30(4), 399–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lahav Y., Price N., Crompton L., Laufer A., & Solomon Z. (2019). Sexual satisfaction in spouses of ex-POWs: The role of PTSD symptoms and self-differentiation. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lahav Y., Rodin R., & Solomon Z. (2015). Somatic complaints and attachment in former prisoners of war: A longitudinal study. Psychiatry, 78(4), 354–366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lahav Y., Stein J. Y., & Solomon Z. (2016). Keeping a healthy distance: Self-differentiation and perceived health among ex-prisoners-of-war’s wives. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 89, 61–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert J. E., Engh R., Hasbun A., & Holzer J. (2012). Impact of posttraumatic stress disorder on the relationship quality and psychological distress of intimate partners: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Family Psychology, 26(5), 729–737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J. J., Gottfried R., & Bride B. E. (2018). Exposure to client trauma, secondary traumatic stress, and the health of clinical social workers: A mediation analysis. Clinical Social Work Journal, 46(3), 228–235. [Google Scholar]

- Mikulincer M., Florian V., & Solomon Z. (1995). Marital intimacy, family support, and secondary traumatization: A study of wives of veterans with combat stress reaction. Anxiety, Stress & Coping, 8(3), 203–213. [Google Scholar]

- Mollica R., Caspi-Yavin Y., Bollini P., Truong T., Tor S., & Lavelle J. (1992). The harvard trauma questionnaire: Validating a cross-cultural instrument for measuring torture, trauma, and posttraumatic stress disorder in Indochinese refugees. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 180(2), 111–116. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Motta R. W., Kefer J. M., Hertz M. D., & Hafeez S. (1999). Initial evaluation of the secondary trauma questionnaire. Psychological Reports, 85(3), 997–1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patrick S., Sells J. N., Giordano F. G., & Tollerud T. R. (2007). Intimacy, differentiation, and personality variables as predictors of marital satisfaction. The Family Journal, 15(4), 359–367. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez L. G., Abrams M. P., López-Martínez A. E., & Asmundson G. J. G. (2012). Trauma exposure and health: The role of depressive and hyperarousal symptoms. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 25(6), 641–648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher K. J., & Hayes A. F. (2008). Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods, 40(3), 879–891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riley K. E., Park C. L., Wilson A., Sabo A. N., Antoni M. H., Braun T. D., … Cope S. (2017). Improving physical and mental health in frontline mental health care providers: Yoga-based stress management versus cognitive behavioral stress management. Journal of Workplace Behavioral Health, 32(1), 26–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizkalla N., & Rahav G. (2016). Differentiation of the self, couples’ intimacy and marital satisfaction: A similar model for Palestinian and Jewish married couples in Israel. International Journal of the Jurisprudence of the Family, 7, 1–32. [Google Scholar]

- Rizkalla N., & Segal S. P. (2018). Well-being and posttraumatic growth among Syrian refugees in Jordan. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 31(2), 213–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizkalla N., & Segal S. P. (2019). War can harm intimacy: Consequences for refugees who escaped Syria. Journal of Global Health, 9(2), 1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizkalla N., Zeevi-Barkay M., & Segal S. P. (2017). Rape crisis counseling: Trauma contagion and supervision. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260517736877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts R. M., Ong N. W.-Y., & Raftery J. (2018). Factors that inhibit and facilitate wellbeing and effectiveness in counsellors working with refugees and asylum seekers in Australia. Journal of Pacific Rim Psychology, 12(e33), 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Rohlof H. G., Knipscheer J. W., & Kleber R. J. (2014). Somatization in refugees: A review. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 49(11), 1793–1804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaefer M. T., & Olson D. H. (1981). Assessing intimacy: The PAIR inventory. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 7(1), 47–60. [Google Scholar]

- Schütte S., Chastang J. F., Malard L., Parent-Thirion A., Vermeylen G., & Niedhammer I. (2014). Psychosocial working conditions and psychological well-being among employees in 34 European countries. International Archives of Occupational and Environmental Health, 87(8), 897–907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selig J. P., & Preacher K. J. (2008). Monte Carlo method for assessing mediation: An interactive tool for creating confidence intervals for indirect effects. [Computer software]. Retrieved from http://quantpsy.org/. [Google Scholar]

- Skowron E. A., & Friedlander M. L. (1998). The differentiation of self inventory: Development and initial validation. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 45(3), 235–246. [Google Scholar]

- Skowron E. A., & Schmitt T. A. (2003). Assessing interpersonal fusion: Reliability and validity of a new DSI fusion with other subscales. Journal of Marital & Family Therapy, 29(2), 209–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skowron E. A., Wester S. R., & Azen R. (2004). Differentiation of self mediates college stress and adjustment. Journal of Counseling & Development, 82(1), 69–78. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor A. K., Gregory A., Feder G., & Williamson E. (2018). ‘We’re all wounded healers’: A qualitative study to explore the well-being and needs of helpline workers supporting survivors of domestic violence and abuse. Health & Social Care in the Community, 27(1), 1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees UNHCR - Syria emergency [Online]. Retrieved from https://www.unhcr.org/en-us/syria-emergency.html

- VanDeusen K. M., & Way I. (2006). Vicarious trauma: An exploratory study of the impact of providing sexual abuse treatment on clinicians’ trust and intimacy. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse, 15(1), 69–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zerach G. (2015). Secondary traumatization among Ex-POWs’ adult children: The mediating role of differentiation of the self. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 7(2), 187–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Citations

- United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees UNHCR - Syria emergency [Online]. Retrieved from https://www.unhcr.org/en-us/syria-emergency.html