Abstract

Background

Percutaneous vertebroplasty has become the treatment of choice for compression fractures. Although the incidence is low, infection after vertebroplasty is a serious complication. The pathogens most often responsible for infection are bacteria. Meanwhile, mycobacterium tuberculosis-induced infection is extremely rare. In this study, we reported our treatment experience with 9 cases of tuberculous spondylitis after vertebroplasty.

Methods

Between January 2001 and December 2015, 5749 patients underwent vertebroplasty or kyphoplasty in our department. Nine cases developed tuberculous spondylitis after vertebroplasty (0.16%). Data on clinical history, laboratory examinations, image, treatment and outcomes were examined.

Results

One male and 8 female patients with a mean age of 75.1 years developed tuberculous spondylitis after vertebroplasty. 5 patients had a history of pulmonary tuberculosis (TB). Revision surgeries were performed from 5 days to 1124 days after vertebroplasty. Seven patients underwent anterior debridement and fusion with or without posterior instrumentation, and 2 cases received posterior decompression and instrumentation only. After operation, the diagnosis of tuberculous spondylitis was confirmed by TB polymerase chain reaction (TB-PCR) or mycobacteria culture. Mean follow-up period after revision surgery was 36.8 months. At the end of follow-up, 1 patient with paraplegia had passed away, 2 needed a wheel chair, 4 required a walker and 2 were able to walk unassisted.

Conclusions

Vertebroplasty is a minimally invasive procedure but still retains some possibility of complications, including TB infection. Patients with a history of pulmonary TB or any elevation of infection parameters should be reviewed carefully to avoid infective complications.

Keywords: Vertebroplasty, Spine infection, Mycobacteria tuberculosis

At a glance commentary

Scientific background on the subject

Percutaneous vertebroplasty is a widely accepted treatment option for vertebral osteoporotic compression fracture. Potential complications of this procedure including cement leakage, re-fracture, adjacent fracture, infection and cement emboli formation. Spine infection after vertebroplasty were not very common. Most reported cases were due to bacteria infection.

What this study adds to the field

In this study, author presented 9 cases of tuberculous spondylitis after vertebroplasty in a country where Mycobacteria tuberculosis infection is endemic. Early diagnosis and prompt surgical intervention combined with anti-tuberculosis medications can lead to acceptable outcome in this devastating condition. Diagnosis and treatment protocols in this study can be used as a guide in further study.

Background

In 1984, Galibert et al. first demonstrated percutaneous vertebroplasty for the treatment of hemangioma in the spine [1]. In recent two decades, percutaneous augmentation with bone cement is a widely accepted modality of treatment for thoracic and lumbar vertebral osteoporotic compression fractures. The effect of pain reduction on patient with compression fracture is significant [2]. However, with the increasing use of vertebroplasty, more and more complications were noted. Potential complication of vertebroplasty including cement leakage with possible spinal cord compression, re-fracture, adjacent level fracture, infection and emboli formation [3], [4], [5], [6], [7]. Within those complications, reports of infectious complications after vertebroplasty were not very common. The largest series of spinal infection after vertebroplasty or kyphoplasty contained only nine patients [8]. Most infectious pathogen after vertebroplasty were bacteria. However, the cases of tuberculosis infection were reported sporadically [9], [10], [11], [12], [13], [14].

In our country, Taiwan, an island located at south east Asia, tuberculosis is a leading notifiable infectious disease. Extra-pulmonary tuberculosis account for about 1/10 of all tuberculosis cases and tuberculous spondylitis is one of the most devastating infection [15]. Although the incidence of tuberculosis had steadily declined in recent decades, we still experienced some cases of tuberculous spondylitis after vertebroplasty. In this article, we presented a case series of nines cases with tuberculous spondylitis after vertebroplasty. Clinical history, image study, treatments, and final outcomes were demonstrated. We also compared similar articles to analyze the risk factor of these patients.

Material and methods

We reviewed all cases that received vertebroplasty or kyphoplasty in our institute between January 2001 and December 2015. Cases of post-operative tuberculosis infection were enrolled. Diagnosis of tuberculous spondylitis must be confirmed by positive mycobacteria culture or tuberculosis polymerase chain reaction (TB-PCR).

We collected patients’ data include age, sex, level(s) of compression fracture, history of pulmonary tuberculosis infection, comorbidity, American society of anesthesiologist (ASA) score, neurological status, magnetic resonance image (MRI), laboratory data, visual analogue scale (VAS) of back pain, type of revision surgery, interval between operations and final outcome. All images were reviewed by a single well-trained radiologist.

Results

Between January 2001 and December 2015, 5749 patients underwent vertebroplasty or kyphoplasty in our department. Nine cases developed tuberculous spondylitis after vertebroplasty (0.16%) and were included in our series.

8 female patients and 1 male patient were enrolled with a mean age (±standard deviation) of 75.1 ± 7.0 years (minimum 66, maximal 90). Comorbidities were found in 8 of 9 patients and were shown below [Table 1]. 5 cases had a history of pulmonary tuberculosis.

Table 1.

Demographics and comorbidities of patients and information of primary intervention.

| Age | Sex | Comorbidities | ASA | History of pulmonary tuberculosis | VP levels | Number of levels | WBC | ESR | CRP | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case 1 | 75 | F | CAD | 3 | Y | T9 | 1 | 7.2 | 24 | 3 |

| Case 2 | 79 | F | HTN, heart failure, CVA | 3 | Y | T11,12 | 2 | 7.1 | NA | NA |

| Case 3 | 66 | M | Duodenal ulcer | 3 | N | L4 | 1 | 6.2 | NA | NA |

| Case 4 | 79 | F | HTN, CAD, PPU | 3 | N | L1 | 1 | 3.0 | 21 | 11 |

| Case 5 | 70 | F | SLE | 3 | Y | T9,10 | 2 | 5.3 | 34 | NA |

| Case 6 | 74 | F | 2 | Y | L1 | 1 | 7.0 | NA | NA | |

| Case 7 | 71 | F | CKD | 3 | N | L1 | 1 | 8.0 | 50 | 71 |

| Case 8 | 72 | F | DM, HTN | 3 | N | L4 | 1 | 3.8 | NA | NA |

| Case 9 | 90 | F | gout | 3 | Y | T8,9 | 2 | 7.0 | 65 | 4.3 |

Abbreviations: ASA: American society of anesthesiology; VP: vertebroplasty; WBC: white blood count; ESR: erythrocyte sedimentation rate; CRP: C-reactive protein; CAD: coronary artery disease; HTN: hypertension; CVA: cerebral vascular accident; PPU: perforated peptic ulcer; SLE: systemic lupus erythematosus; CKD: chronic kidney disease.

Before primary surgery, spine MRI without contrast were arranged in all patient. Low-signal-intensity band on T1 and T2-weighted image were checked to confirmed the diagnosis of acute osteoporotic compression fracture. WBC count were all within normal range before primary surgery. After completed pre-operation survey, all 9 patients received vertebroplasty, with a total of 12 segments of cement augmented spine.

The interval between vertebroplasty and revision surgery ranged from 5 to 1125 days, with a mean of 250 days. Infection parameters were higher in all patients before revision surgery [Table 2]. The indication of revision surgery included low back pain (all 9 patients) and neurologic deficits (5 of 9 patients).

Table 2.

Pre-revision clinical data and post-revision condition.

| Interval (days) | Indication for revision | pre-OP VAS | Neurologic status | WBC | ESR | CRP | OP method | Blood loss | OP time | TB - PCR | AFS | Culture | Follow up (months) | Outcome | post-OP VAS | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case 1 | 735 | LBP, lower limbs weakness | 7 | Frenkel C | 5.7 | 68 | 11.4 | T9-10 ant. debridement and fusion | 400 | 130 | – | N | Y | 6 | paraplegia, die | – |

| Case 2 | 7 | LBP, fever | 7 | Frenkel E | 8.2 | 26 | 49 | T11-12 ant. debridement and fusion; T8-L3 post. instrumentation | 1200 | 409 | Y | N | Y | 62 | walker support | 4 |

| Case 3 | 62 | LBP | 8 | Frenkel E | 4.9 | 35 | 4.9 | L3-5 ant. debridement and fusion; L2-5 post. instrumentation | 500 | 270 | Y | N | Y | 66 | normal walking | 2 |

| Case 4 | 129 | LBP | 8 | Frenkel E | 4.2 | 33 | 33.2 | T12-L2 ant. debridement and fusion; T11-L3 post. instrumentation | 400 | 289 | Y | Y | Y | 15 | normal walking | 2 |

| Case 5 | 117 | LBP, lower limbs weakness | 8 | Frenkel C | 11.5 | 50 | 119.6 | T9-10 laminectomy; T6-L2 post. instrumentation | 500 | 262 | – | N | Y | 9 | on wheel chair | 3 |

| Case 6 | 5 | LBP, lower limbs weakness | 9 | Frenkel C | 6.4 | 56 | 42.4 | T12-L1 ant.debridement and fusion; T10-L4 post. instrumentation | 1000 | 300 | – | Y | Y | 12 | walker support | 2 |

| Case 7 | 34 | LBP, lower limbs weakness | 8 | Frenkel D | 5.5 | 31 | 31.5 | L1 ant.debridement and fusion; T10-L3 post. instrumentation | 350 | 388 | – | Y | Y | 96 | walker support | 1 |

| Case 8 | 1124 | LBP | 6 | Frenkel E | 8.2 | 39 | 3.2 | L3-L5 ant.debridement and fusion; L2-S1 post. instrumentation | 1100 | 237 | Y | N | Y | 60 | walker support | 4 |

| Case 9 | 33 | LBP, lower limbs paralysis urine incontinence | 8 | Frenkel B | 9.7 | 95 | 115 | T8-9 laminectomy; T6-L2 post. instrumentation | 900 | 231 | N | N | Y | 6 | on wheel chair | 3 |

Abbreviations: VAS: visual analogue scale; WBC: white blood count; ESR: erythrocyte sedimentation rate; CRP: C-reactive protein; LBP: low back pain; OP: operation; PCR: polymerase chain reaction; AFS: acid-fast stain; ant: anterior; post: posterior.

At revision surgery, 7 cases underwent anterior debridement and reconstruction surgery, 6 of which also received posterior instrumentation for augmentation. 2 patients received posterior decompression, fusion and instrumentation. Specimens were obtained during the surgery and the diagnosis of tuberculous spondylitis were confirmed by TB-PCR or mycobacteria culture result [Table 2].

Mean follow-up period after revision surgery was 36.8 months. At the end of follow-up, 1 patient passed away with paraplegia, 2 were on wheelchair, 4 patients required a walker, 2 improved functionally and could walk unassisted. All patient had improvement in VAS score but none of them were completely pain-free at the end of follow-up.

Case presentation

Case 4

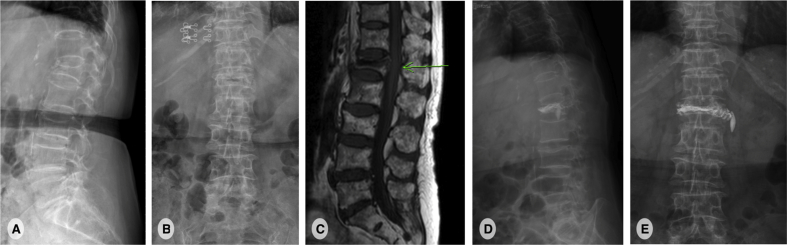

This is a 80-year-old woman with history of hypertension, coronary artery disease and perforated peptic ulcer. She had persistent low back pain after a falling down accident 1 week ago. There was no other associated symptoms like fever or neurologic deficits. Physical examination showed midline back tenderness at the area of T-L junction. Bilateral lower limb muscle power were full and symmetric. Plain film revealed L1 compression fracture with vacuum phenomenon [Fig. 1]. MRI also favored an acute osteoporotic compression fracture. Therefore, L1 vertebroplasty was arranged and her back pain improved dramatically after that. She was discharged 2 days after the procedure.

Fig. 1.

A 80-year-old woman with a L1 osteoporotic compression fracture. (A, B): plain film shows L1 and L3 compression fracture with local kyphosis.(C): Lumbar spine T1-weighted sagittal magnetic resonance image reveals a low signal intensity lesion at L1, compatible with new L1 compression fracture. (D, E): plain film shows adequate cement filling in L1 vertebral body

However, her low back pain recurred 4 months after the vertebroplasty. There was no fever or neurologic deficits. Laboratory data showed elevated CRP (11–> 33.2) compared with previous study. MRI and computed tomography (CT) were arranged and showed fluid accumulation and paravertebral abscess formation, suspect spondylitis [Fig. 2]. Therefore, combined surgery with T12-L2 anterior debridement and fusion with T11-L3 posterior instrumentation were performed [Fig. 3]. TB-PCR and culture obtained during operation both came out to be positive, confirmed the diagnosis of tuberculous spondylitis. After operation, the pain improved and kyphotic deformity was corrected. Anti-tuberculosis medications with the regimen of Rifampin 470 mg, Isoniazid 320 mg, Pyrazinamide 1000 mg and Ethambutol 800 mg daily were given. 2 months after the revision surgery, the patient could walk smoothly and the follow-up CRP level achieved normal level. We kept Rifanah (Rifampin 450 mg and Isoniazid 300 mg daily) for another 6 months and completed the treatment course.

Fig. 2.

(A):T2-weighted magnetic resonance image revealed a retropulsive lesion at L1 with cord compression. (B): non-contrast computed tomography showed local fluid accumulation with paravertebral abscess formation.

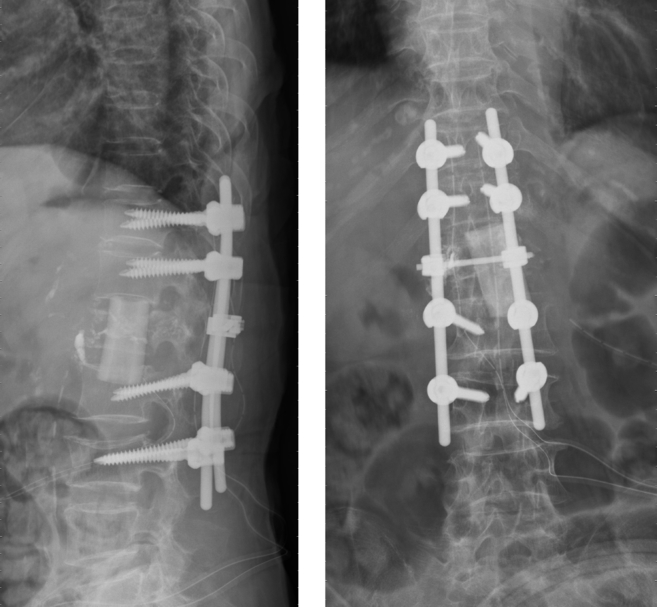

Fig. 3.

Plain film after anterior debridement, fusion and posterior instrumentation from T11-L3.

Case 9

This is a 90-year-old woman with history of gout. She didn't have any recent trauma history. However, gradually onset back pain was noted since 2 months ago. The pain was located at midline with radiation to left flank and subcostal region. Due to above reasons, she visited our hospital for help.

At our out-patient clinic, physical examinations showed full and symmetric lower limbs muscle power. Plain film revealed T8 compression fracture with multiple calcified nodule in mediastinum [Fig. 4]. MRI showed hypointensity lesions at T8 and T9 vertebral body in T1-weighted image, compatible with non-healed osteoporotic compression fracture. Therefore, T8 and T9 vertebroplasty were performed and her back pain improved a lot after that [Fig. 5].

Fig. 4.

(A, B): plain film showed T8 osteoporotic compression fracture with severe kyphosis. (C): T1-weighted magnetic resonance image showed low signal intensity lesion at T8 and T9.

Fig. 5.

Plain film after percutaneous T8, T9 vertebroplasty.

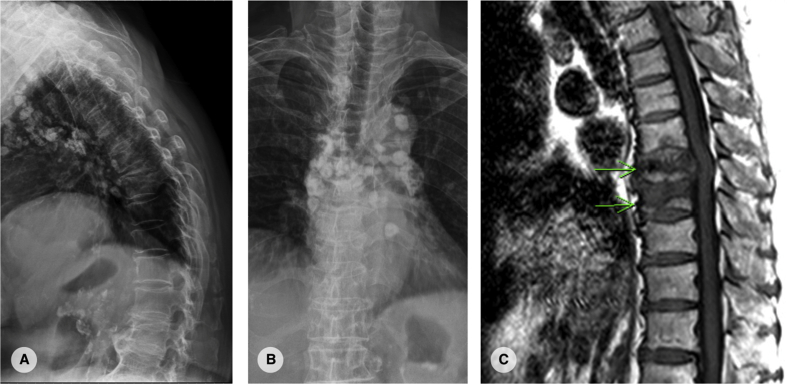

However, during follow-up period, the patient complained about recurrent back pain with bilateral lower limbs weakness. 1 month after vertebroplasty, the patient suffered from complete paraplegia with urine incontinence. Follow-up MRI showed a retropulsive lesion at T8 level with resultant compressive myelopathy [Fig. 6]. Therefore, T8-9 decompression with laminectomy and T6-L2 posterior instrumentation were done as salvage procedure. TB-PCR from intra-operative tissue showed negative result. However, mycobacteria culture came out to be positive for mycobacteria tuberculosis growth 1 month after operation, confirmed the diagnosis of tuberculous spondylitis. Therefore, we started anti-tuberculosis medication with Rifampin 600 mg, Isoniazid 300 mg and Ethambutol 800 mg daily. Since she had history of gout, we didn't prescribed Pyrazinamide and extend the course of anti-tuberculosis treatment to 9 months.

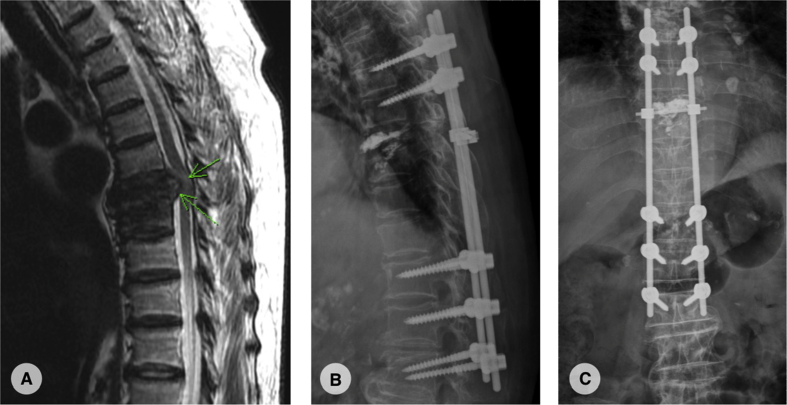

Fig. 6.

(A): T2-weighted magnetic resonance image showed retropulsive lesion at T8. Intramedullary hyper intensity suggestive of compressive myelopathy. (B, C): plain film after T8,9 laminectomy and posterior instrumentation from T6-L2.

She received rehabilitation programs after operation but still had some residual disability as bilateral muscle weakness (MP:4) and urine incontinence. Now she had partially dependent activity daily living (ADL) function and use wheel chair for ambulation.

Discussion

Percutaneous augmentation with bone cement has become a common modality of treatment for thoracic and lumbar vertebral osteoporotic fractures [2], [16], [17]. Although incidence was low, infection after vertebroplasty is a serious complication. Most infections were pyogenic infection caused by bacteria. Mycobacteria tuberculosis induced infection after vertebroplasty was extremely rare. To the best of our knowledge, there were only 7 cases reported by now [9], [10], [11], [12], [13], [14]. This time, we present a case series of 9 cases from 2001 to 2015 in our institute.

The exact etiology of tuberculous spondylitis after vertebroplasty is still not clear. Kang et al. had described a case of tuberculous spondylitis after vertebroplasty [11]. Their patient developed severe back pain within 1 month after the primary procedure and they suggested that misdiagnosis before primary intervention is a possible explanation. Since osteoporotic compression fracture and tuberculous spondylitis shared some common characteristic on MRI findings [18], [19], [20], [21], we might missed some cases of tuberculosis infection if we didn't obtained tissue proof during vertebroplasty. In our 9 cases, 2 of them had early infection within 1 month and both of them had history of pulmonary tuberculosis. Therefore, insidious tuberculosis infection of spine which wasn't been detected by image or laboratory findings before vertebroplasty was highly suspected. However, routinely obtain tissue proof during percutaneous vertebroplasty is not cost-effective. Previous research suggested that it should only reserved for the patients where the preoperative evaluation raises the suspicion of a non-osteoporotic etiology [22]. The timing of tissue proof for these patients is still under debate.

If there was not misdiagnosis, how do the mycobacteria get to the surgical site after vertebroplasty? Previous studies had suggested two mechanisms: hematogenous spreading of active pulmonary TB from lung to vertebra, or local reactivation of an already present inactivated tuberculous focus. The “locus minoris resistentiae” theory, which first been described by Agostoni et al., could be an adequate explanation for surgical site infection [9], [14], [23], [24], [25]. The theory defined a “place of less resistance”, a anatomical site which is more susceptible of infection after trauma or an induced trauma event (ex: surgery). Vertebroplasty, although it was a minimally-invasive procedure, still cause some blood loss and local inflammation. It could be seen as an induced trauma event, which triggered the infection process. Macrophage migration during the inflammation process might bring the mycobacteria to surgical site. Besides, fractured osteoporotic vertebral body with possible hematoma formation could served as a good microenvironment for mycobacteria growth. In patients with history of pulmonary tuberculosis, this theory explained why and how the mycobacteria get there. In patients without history of pulmonary tuberculosis, recent contact with active TB patient and months of incubation may also lead to the result of tuberculous spondylitis.

For a patient who sustained from persisted severe back pain or newly onset neurologic deficit after vertebroplasty, which infection is suspected, a major salvage procedure is inevitable. There was no consensus in previous studies whether anterior or posterior approach is preferred in pyogenic spondylitis or tuberculous spondylitis [26], [27], [28], [29], [30], [31], [32]. Early practice suggested 2-stage surgery in pyogenic spondylitis patient to avoid instrumentation in an contaminated bed. However, Oga et al. had demonstrated that mycobacteria had less biofilm producing ability than bacteria so instrumented stabilization in a tubercular infected bed seems to be safe if meticulous debridement is performed [33]. In early 2000s, anterior debridement, bone grafting and posterior instrumentation were standard treatment for these patient. However, recent studies showed that posterior debridement with instrumentation had comparable or even better result than traditional methods, expect for those who had psoas abscess [26], [27], [28], [29]. Even minimal invasive surgery had some success in patient with tuberculous spondylitis but still need some comparable study. In our series, 7 patients were treated with anterior debridement with or without posterior instrumentation. 2 patients received posterior decompression and instrumentation only. Both procedure lead to acceptable outcome with much improvement in VAS of back pain. However, not all patients were pain free and some still had residual disability. In our case series, there was 1 patient, which was treated with anterior debridement, still had paraplegia after surgery and passed away due to other co-morbidity. There was no significant difference in blood loss and operation time between 2 groups. In our experience, both procedure could be adequate for these patient but still need more cases to demonstrate.

In our case series, all patient had a positive intra-OP tissue culture for tuberculosis. However, mycobacteria was known for it slow growing characteristic. It usually cost a months until the culture yield positive result. Acid-fast stain seemed to be an inadequate diagnostic tool due to its low sensitivity. TB-PCR is currently the best method for quick diagnosis if the equipments were available. If tuberculous spondylitis was confirmed, anti-tuberculosis treatments should initiate as soon as possible. Combination of rifampicin, isoniazid, ethambutol, and pyrazinamide for two months followed by combination of rifampicin and isoniazid for at least 6 months is the most frequently used protocol for tuberculous spondylitis [34], [35], [36], [37]. In our 9 cases, all cases except the one who passed away completed 6 months anti-tuberculosis medication. It seemed to be an adequate management in adjunct with surgical debridement.

The treatment for tuberculous spondylitis after percutaneous vertebroplasty works well with current protocols of medical treatments after surgical debridement and stabilization. Posterior one-staged surgery with debridement and instrumentation showed result not inferior to anterior debridement and need more cases to prove. Future research might aim to decrease the rate of tuberculous spondylitis after vertebroplasty and achieve early diagnosis. For patient who had history of pulmonary tuberculosis, intra-OP culture for mycobacteria might be a reasonable choice to avoid delay diagnosis. On the other hand, during recent vertebroplasty, we had apply antibiotics-loaded cement for the prevention of pyogenic infection. Anti-tuberculosis drug loaded cement had been reported to be used in the treatment of musculoskeletal tuberculosis, especially osteomyelitis or arthritis [38], [39], [40], [41]. It might also had a role on preventing tuberculous spondylitis after vertebroplasty, especially in patient with active pulmonary tuberculosis.

Conclusions

We presented 9 cases of tuberculous spondylitis after vertebroplasty. It is a devastating infection which required major surgery for salvage with a relevant part of residual disability. Patients with a history of pulmonary TB or any elevation of infection parameters should be reviewed carefully before vertebroplasty. Avoiding any delay in correct diagnosis is the utmost importance which lead to an acceptable outcome.

Conflict of interest

There is no conflict of interest in this study.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Chang Gung University.

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bj.2019.04.002.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Galibert P., Deramond H., Rosat P., Le Gars D. Preliminary note on the treatment of vertebral angioma by percutaneous acrylic vertebroplasty. Neurochirurgie. 1987;33:166–168. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Muijs S.P., van Erkel A.R., Dijkstra P.D. Treatment of painful osteoporotic vertebral compression fractures: a brief review of the evidence for percutaneous vertebroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2011;93:1149–1153. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.93B9.26152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Makary M.S., Zucker I.L., Sturgeon J.M. Venous extravasation and polymethylmethacrylate pulmonary embolism following fluoroscopy-guided percutaneous vertebroplasty. Acta Radiol Open. 2015;4 doi: 10.1177/2058460115595660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhao Y., Liu T., Zheng Y., Wang L., Hao D. Successful percutaneous retrieval of a large pulmonary cement embolus caused by cement leakage during percutaneous vertebroplasty: case report and literature review. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2014;39:E1616–E1621. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0000000000000613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sidhu G.S., Kepler C.K., Savage K.E., Eachus B., Albert T.J., Vaccaro A.R. Neurological deficit due to cement extravasation following a vertebral augmentation procedure. J Neurosurg Spine. 2013;19:61–70. doi: 10.3171/2013.4.SPINE12978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Matouk C.C., Krings T., Ter Brugge K.G., Smith R. Cement embolization of a segmental artery after percutaneous vertebroplasty: a potentially catastrophic vascular complication. Interv Neuroradiol. 2012;18:358–362. doi: 10.1177/159101991201800318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ha K.Y., Kim K.W., Kim Y.H., Oh I.S., Park S.W. Revision surgery after vertebroplasty or kyphoplasty. Clin Orthop Surg. 2010;2:203–208. doi: 10.4055/cios.2010.2.4.203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abdelrahman H., Siam A.E., Shawky A., Ezzati A., Boehm H. Infection after vertebroplasty or kyphoplasty. A series of nine cases and review of literature. Spine J. 2013;13:1809–1817. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2013.05.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ge C.Y., He L.M., Zheng Y.H., Liu T.J., Guo H., He B.R. Tuberculous spondylitis following kyphoplasty: a case report and review of the literature. Medicine (Baltim) 2016;95:e2940. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000002940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zou M.X., Wang X.B., Li J., Lv G.H., Deng Y.W. Spinal tuberculosis of the lumbar spine after percutaneous vertebral augmentation (vertebroplasty or kyphoplasty) Spine J. 2015;15:e1–e6. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2015.02.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kang J.H., Kim H.S., Kim S.W. Tuberculous spondylitis after percutaneous vertebroplasty: misdiagnosis or complication? Korean J Spine. 2013;10:97–100. doi: 10.14245/kjs.2013.10.2.97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim H.J., Shin D.A., Cho K.G., Chung S.S. Late onset tuberculous spondylitis following kyphoplasty: a case report and review of the literature. Korean J Spine. 2012;9:28–31. doi: 10.14245/kjs.2012.9.1.28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ivo R., Sobottke R., Seifert H., Ortmann M., Eysel P. Tuberculous spondylitis and paravertebral abscess formation after kyphoplasty: a case report. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2010;35:E559–E563. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181ce1aab. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bouvresse S., Chiras J., Bricaire F., Bossi P. Pott's disease occurring after percutaneous vertebroplasty: an unusual illustration of the principle of locus minoris resistentiae. J Infect. 2006;53:e251–e253. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2006.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Millet J.P., Moreno A., Fina L., del Bano L., Orcau A., de Olalla P.G. Factors that influence current tuberculosis epidemiology. Eur Spine J. 2013;22:539–548. doi: 10.1007/s00586-012-2334-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rao R.D., Singrakhia M.D. Painful osteoporotic vertebral fracture. Pathogenesis, evaluation, and roles of vertebroplasty and kyphoplasty in its management. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003;85-A:2010–2022. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chiras J., Sola-Martinez M.T., Weill A., Rose M., Cognard C., Martin-Duverneuil N. Percutaneous vertebroplasty. Rev Med Interne. 1995;16:854–859. doi: 10.1016/0248-8663(96)80802-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li T., Liu T., Jiang Z., Cui X., Sun J. Diagnosing pyogenic, brucella and tuberculous spondylitis using histopathology and MRI: a retrospective study. Exp Ther Med. 2016;12:2069–2077. doi: 10.3892/etm.2016.3602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Khalid M., Siddiqui M.A., Qaseem S.M., Mittal S., Iraqi A.A., Rizvi S.A. Role of magnetic resonance imaging in evaluation of tubercular spondylitis: pattern of disease in 100 patients with review of literature. JNMA J Nepal Med Assoc. 2011;51:116–121. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Currie S., Galea-Soler S., Barron D., Chandramohan M., Groves C. MRI characteristics of tuberculous spondylitis. Clin Radiol. 2011;66:778–787. doi: 10.1016/j.crad.2011.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jung N.Y., Jee W.H., Ha K.Y., Park C.K., Byun J.Y. Discrimination of tuberculous spondylitis from pyogenic spondylitis on MRI. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2004;182:1405–1410. doi: 10.2214/ajr.182.6.1821405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pneumaticos S.G., Chatziioannou S.N., Savvidou C., Pilichou A., Rontogianni D., Korres D.S. Routine needle biopsy during vertebral augmentation procedures. Is it necessary? Eur Spine J. 2010;19:1894–1898. doi: 10.1007/s00586-010-1388-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chan E.D., Kong P.M., Fennelly K., Dwyer A.P., Iseman M.D. Vertebral osteomyelitis due to infection with nontuberculous Mycobacterium species after blunt trauma to the back: 3 examples of the principle of locus minoris resistentiae. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;32:1506–1510. doi: 10.1086/320155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kainz J., Stammberger H. The roof of the anterior ethmoid: a locus minoris resistentiae in the skull base. Laryngol Rhinol Otol (Stuttg) 1988;67:142–149. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Agostoni G. Aneurysms of the thoracic aorta and traumatism; region of the aortic isthmus; locus minoris resistentiae. Arch Mal Coeur Vaiss. 1953;46:550–558. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Luo C., Wang X., Wu P., Ge L., Zhang H., Hu J. Single-stage transpedicular decompression, debridement, posterior instrumentation, and fusion for thoracic tuberculosis with kyphosis and spinal cord compression in aged individuals. Spine J. 2016;16:154–162. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2013.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang X., Pang X., Wu P., Luo C., Shen X. One-stage anterior debridement, bone grafting and posterior instrumentation vs. single posterior debridement, bone grafting, and instrumentation for the treatment of thoracic and lumbar spinal tuberculosis. Eur Spine J. 2014;23:830–837. doi: 10.1007/s00586-013-3051-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Garg N., Vohra R. Minimally invasive surgical approaches in the management of tuberculosis of the thoracic and lumbar spine. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2014;472:1855–1867. doi: 10.1007/s11999-014-3472-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang H.Q., Li J.S., Zhao S.S., Shao Y.X., Liu S.H., Gao Q. Surgical management for thoracic spinal tuberculosis in the elderly: posterior only versus combined posterior and anterior approaches. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2012;132:1717–1723. doi: 10.1007/s00402-012-1618-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shin J.H., Ha K.Y., Kim K.W., Lee J.S., Joo M.W. Surgical treatment for delayed pyogenic spondylitis after percutaneous vertebroplasty and kyphoplasty. Report of 4 cases. J Neurosurg Spine. 2008;9:265–272. doi: 10.3171/SPI/2008/9/9/265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mummaneni P.V., Walker D.H., Mizuno J., Rodts G.E. Infected vertebroplasty requiring 360 degrees spinal reconstruction: long-term follow-up review. Report of two cases. J Neurosurg Spine. 2006;5:86–89. doi: 10.3171/spi.2006.5.1.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Alfonso Olmos M., Silva Gonzalez A., Duart Clemente J., Villas Tome C. Infected vertebroplasty due to uncommon bacteria solved surgically: a rare and threatening life complication of a common procedure: report of a case and a review of the literature. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2006;31:E770–E773. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000240202.91336.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Oga M., Arizono T., Takasita M., Sugioka Y. Evaluation of the risk of instrumentation as a foreign body in spinal tuberculosis. Clinical and biologic study. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1993;18:1890–1894. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199310000-00028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bakhsh A. Medical management of spinal tuberculosis: an experience from Pakistan. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2010;35:E787–E791. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181d58c3c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gupta S.K., Mohindra S., Sharma B.S., Gupta R., Chhabra R., Mukherjee K.K. Tuberculosis of the craniovertebral junction: is surgery necessary? Neurosurgery. 2006;58:1144–1150. doi: 10.1227/01.NEU.0000215950.85745.33. Discussion-50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Moon M.S., Moon Y.W., Moon J.L., Kim S.S., Sun D.H. Conservative treatment of tuberculosis of the lumbar and lumbosacral spine. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2002;398:40–49. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200205000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bhojraj S., Nene A. Lumbar and lumbosacral tuberculous spondylodiscitis in adults. Redefining the indications for surgery. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2002;84:530–534. doi: 10.1302/0301-620x.84b4.12363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Leclere L.E., Sechriest V.F., 2nd, Holley K.G., Tsukayama D.T. Tuberculous arthritis of the knee treated with two-stage total knee arthroplasty. A case report. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009;91:186–191. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.G.01421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Anguita-Alonso P., Rouse M.S., Piper K.E., Jacofsky D.J., Osmon D.R., Patel R. Comparative study of antimicrobial release kinetics from polymethylmethacrylate. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2006;445:239–244. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000201167.90313.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Su J.Y., Huang T.L., Lin S.Y. Total knee arthroplasty in tuberculous arthritis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1996;323:181–187. doi: 10.1097/00003086-199602000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Masri B.A., Duncan C.P., Jewesson P., Ngui-Yen J., Smith J. Streptomycin-loaded bone cement in the treatment of tuberculous osteomyelitis: an adjunct to conventional therapy. Can J Surg. 1995;38:64–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.