Abstract

Previous research has shown that antisocial, borderline, narcissistic and histrionic personality disorders, also known as the Cluster B personality disorders in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders–Fifth Edition (DSM–5), are commonly raised in lawsuits. Cluster B disorders are characterized by problems with emotion regulation, impulsivity and interpersonal conflicts. Without question, individuals diagnosed with a Cluster B disorder possess traits that make them more susceptible to becoming involved in litigation; however, to date there has been no research on how the disorders interact with the judicial system. This study surveyed litigant success of Cluster B personality disorders in United States federal and state case law. Results showed that both criminal and civil litigants tended to be unsuccessful in their cases. Overall, this study demonstrated that court opinions can provide a window into the psychology of trial litigants and how personality can affect trial outcomes.

Key words: antisocial, borderline, case law, Cluster B, forensic, histrionic, litigation, narcissistic, personality disorders

In ‘The Intractable Client’ (Feinberg & Greene, 1997), an article on personality disorders geared towards family law lawyers, psychologists Rhoda Feinberg and James Tom Greene wrote:

These are the clients whom you will most see in protracted litigation or mediation. They make up the bulk of custody commissioner, court master, and special guardian ad litem cases. . . . People with personality disorders usually ‘dig in’ and maintain their rigid attitudes and perceptions throughout the legal process. (pp. 354–355)

Although Feinberg and Greene (1997) penned this article 20 years ago based on their experiences in the family court system, their words still resonate today at a time when personality disorders continue to be problematic for the judicial system. Little is actually known about court decisions concerning personality diagnoses due to the lack of empirical legal research available. In fact, Feinberg and Greene (1997), though they state that the majority of family law cases involve individuals with personality disorder, offered no data to validate their point.

What we do know about personality disorders and the law is limited. Legally relevant research on personality disorders has focused predominantly on the criminal law context, largely in part due to the overwhelming prevalence rates of the Cluster B personality disorders within correctional settings (Johnson & Elbogen, 2013). This study aimed to examine personality disorders in both criminal and civil case law by first providing background on personality disorders in general, distinguishing Cluster B personalities from other personality disorders, and then lastly describing the available literature on personality disorders, the law and the courts.

Cluster B Personality Disorders

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders–Fifth Edition (DSM–5) divides the 10 personality disorders into clusters; this study is focused on Cluster B, which includes antisocial, borderline, histrionic and narcissistic personality disorders (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Individuals with a Cluster B personality typically present as ‘dramatic, emotional, or erratic’ (American Psychiatric Association, 2013, p. 646), although some have argued that the predominant theme is a lack of empathy (Kraus & Reynolds, 2001). Cluster B personality disorders account for the least prevalent of the clusters when compared with Cluster A (5.7%) and Cluster C (6.0%) (American Psychiatric Association, 2013; Lenzenweger, Lane, Loranger, & Kessler, 2007). As with many of the other personality clusters, patients with Cluster B personalities do not typically seek out treatment on their own and are frequently referred by courts for treatment (Hatchett, 2015). The following provides brief descriptions of the criteria and general considerations of each of the personality disorders listed in Cluster B.

Antisocial Personality Disorder

Antisocial personality disorder (ASPD) is characterized by persistently violating or disregarding others’ rights, committing crimes, deceiving others, behaving impulsively, exhibiting agitation through frequent fights/altercations, acting recklessly, and lacking responsibility and empathy (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Adolescents who exhibited conduct disorder are typically diagnosed with ASPD as adults if they continue behaviors consistent with ASPD (American Psychiatric Association, 2013).

Individuals with ASPD may be prone to legal problems for several reasons. First, ASPD has frequently been associated with the commission of criminal offenses (Hodgkins & Côté, 1993; Roberts & Coid, 2010). Deceitfulness, reckless behavior, impulsivity and lack of empathy increase the individual's risk of becoming involved in the legal system. ASPD is the one personality disorder linked to psychopathy, a condition with some overlapping features of ASPD including deceit and manipulation (American Psychiatric Association, 2013; Hare, Hart, & Harpur, 1991). Accordingly, ASPD is more commonly diagnosed in correctional populations where some studies have estimated that more than 70% of inmates have the personality disorder (Coid, 2002). Second, individuals with ASPD may fail to fulfill their parental obligations, possibly resulting in child neglect, child endangerment or even abuse (American Psychiatric Association, 2013).

Borderline Personality Disorder

Criteria for borderline personality disorder (BPD) include intense mood dysregulation, difficulties with impulse control, fear of abandonment, transient psychotic-like symptoms, volatile relationships with alternating devaluing and idealizing, and absence of a cohesive self-identity (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Females are overrepresented (75%) in diagnosis of the disorder, and marital distress including separation and divorce are prevalent (American Psychiatric Association, 2013).

Out of all of the personality disorders within Cluster B, BPD is the disorder most commonly associated with suicidal gestures (García-Nieto, Blasco-Fontecilla, de León-Martinez, & Baca-García, 2014) and suicide completions (Pompili, Girardi, Ruberto, & Tatarelli, 2005). It is also the ‘only personality disorder whose literature is clearly alive and growing’ with significant increases in published studies since 1980 (Blashfield & Intoccia, 2000, p. 473).

Similar to ASPD, BPD has been linked to several legal problems; however, unlike the ASPD patient, the BPD patient is frequently the plaintiff. BPD patients have been known to sue their providers for malpractice related to sexual misconduct or suicide (Appelbaum & Gutheil, 2007; Simon, 1995). Accordingly, risk management practices have been heavily emphasized when working with this population (Fusco, 2015; Goodman, Roiff, Oakes, & Paris, 2012; Gregory, 2012; Stone, 1993).

Narcissistic Personality Disorder

Narcissistic personality disorder (NPD) is characterized by grandiosity, idealistic fantasies, belief in the individual's uniqueness, entitlement, attention-seeking behaviors, manipulation and a lack of empathy (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). There is evidence that also suggests a more covert type of NPD that is more indifferent than bombastic in nature, which has been hypothesized to be due to experiencing intense shame over inner grandiose thoughts (Gabbard, 1994). Despite their bravado, individuals with NPD typically have fragile egos prone to deep feelings of hurt from criticism (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). NPD is more commonly diagnosed in men with 50–75% of patients being male (American Psychiatric Association, 2013) compared to female, and treatment typically involves managing feelings of anger, depression and shame if the NPD individual even enters into psychotherapy (Kraus & Reynolds, 2001).

Histrionic Personality Disorder

Histrionic personality disorder (HPD) is characterized by a pattern of excessive yet shallow displays of emotion, attention-seeking behaviors, suggestibility and dramatic flair (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Like with BPD, individuals with HPD may present with suicidal behaviors for attention and are most often women (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). But unlike BPD, HPD is lacking in empirical research (Kraus & Reynolds, 2001) and is considered ‘flat’ in literature growth (Blashfield & Intoccia, 2000, p. 473). Accordingly, little is known about HPD patients and their development; it has been posited, though, that HPD developed out of a craving for attention from caregivers and that psychotherapy should focus on managing the HPD patient's need for attention (Kraus & Reynolds, 2001).

Psychiatric Disorders and Case Law

Reviews of psychiatric disorders in case law or legal precedent are limited to a few studies. The diagnosis of multiple personalities, now referred to as dissociative identity disorder (DID), for example, was studied in part because the controversy surrounding the disorder combined with the conundrum of how to use it as a defense to crimes resulted in interesting legal issues (Appelbaum & Greer, 1994; Dawson, 1999; James, 1998; Radwin, 1991). Other reviews of psychology and case law have examined neurodevelopmental disorders such as autism spectrum disorders (ASD; Freckelton, 2013) and fetal alcohol syndrome (FAS; Douds, Stevens, & Sumner, 2012), both diagnoses of which can be especially relevant throughout every step of a criminal trial. ASD in particular have been used to show that defendants lack the capability of forming the specific intent necessary to satisfy many crimes (Freckelton & List, 2009).

In the Douds et al. (2012) study, researchers conducted the first review of federal case law and FAS using the legal search engine LexisNexis. They found that most of the cases (81 out of 131) emerged after 2005, possibly signifying a shift in the courts post Atkins (2002)1. (Douds et al., 2012). Findings indicated that cases with defendants who introduced evidence of a FAS diagnosis typically fell within the jurisdiction of the Eighth2. or Ninth3. United States Circuit Court of Appeals (Douds et al., 2012). The District Court in Texas heard the most FAS cases out of any district court, and as a venue, Texas denied many defendants presenting with FAS with only 32% of defendants succeeding on their claims (Douds et al., 2012). Further results showed that all of the courts found evidence of FAS relevant under Federal Rules of Evidence (FRE) rule 401, which requires that evidence has ‘any tendency to make a fact more or less probable than it would be without the evidence and that the fact is of consequence in determining the action’; however, Douds et al. found that the courts differed when it came to analyzing FAS evidence under the FRE rule 403 test for ‘probative value’ – some courts viewed the evidence as more persuasive in the context of their respective cases while others viewed it as less so. Additionally, though all of the courts admitted FAS evidence, researchers discovered that many courts ‘lumped the diagnoses with a myriad other issues and diagnoses,’ thereby losing some of the distinct value that evidence of a FAS diagnosis has to offer in a criminal defense (Douds et al., 2012, p. 498). The mixed results from Douds et al.'s study demonstrated that while courts have increasingly admitted evidence of mental health issues, they have been unsure of how to utilize certain diagnoses in their decision-making process and how much weight to give such evidence.

In an extensive study, Denno (2015) investigated how neuropsychological evidence has been used in criminal law. Similar to Douds et al.'s (2012) research, Denno collected data through legal search engines and found 800 criminal cases spanning two decades that were categorized as presenting either imaging (e.g. computed tomography, CT, scan; magnetic resonance imaging, MRI; electroencephalography, EEG, etc.) or nonimaging tests (e.g. Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale, WAIS; Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory, MMPI; Rorschach, etc.). Denno found that most of the defendants in the cases reviewed had been charged with murder and attempted to use neuroscience to inform not guilty pleas as well as to provide mitigating factors in the sentencing phase. Further, Denno's results showed that neuroscience evidence was commonly used to support ineffective assistance of counsel claims under Strickland v Washington (1984),4. especially in capital punishment cases, noting that courts ‘not only expect attorneys to investigate and use available neuroscience evidence in their cases when it is appropriate, but they penalize attorneys who neglect this obligation’ (p. 544). Denno's research thus demonstrated the crucial role that psychological evidence can play in a defendant's case.

Cluster B in Criminal Law

Research in forensic psychology on Cluster B personality disorders has typically focused on criminal law and antisocial personality (Coid, 2002; Coid et al., 2006; Hodgins & Côté, 1993) or criminal law and borderline personality (Howard, Huband, Duggan, & Mannion, 2008; Sansone, Watts, & Wiederman, 2014; Sisti & Caplan, 2012). In fact, antisocial personality has been called the ‘primary focus within the criminal forensic realm’ (Johnson & Elbogen, 2013, p. 207), yet no literature on the disorder with regards to case law exists. Narcissistic personality has been correlated in a few studies with crimes against others (Keeney et al., 1997), homicide (Coid, 2002), and fraud and forgery violations (Roberts & Coid, 2010). Borderline personality has been linked to arson charges (Coid, 2002); however, a follow-up study showed that there was no association with the disorder and criminal offenses (Roberts & Coid, 2010).

Research has also linked borderline personality to the crime of stalking (Lewis, Fremouw, Del Ben, & Farr, 2001; Ménard & Pincus, 2014; Sansone & Sansone, 2010). In a retrospective study conducted in an acute psychiatric unit, Sandberg, McNeil, and Binder (1998) found that 8 out of the 17 patients (47%) who stalked, threatened or harassed staff following discharge met criteria for a personality disorder. Although Sandberg et al. did not identify which personality disorder in their study, the literature has correlated borderline personality with being a stalker (Sansone & Sansone, 2010) as well as a victim of stalking (Ménard & Pincus, 2014). Demographic data suggested that stalkers were more likely to be White males, unmarried and with previous hospitalizations (Sandberg, McNiel, & Binder, 1998).

Cluster B in Civil Law

Because the primary focus of personality disorders and the law centers around antisocial personality and criminal law, much is left to be studied in civil law research. In fact, the function of the mental health history of a litigant in civil law has been called ‘far less clear’ when compared to criminal law (Smith, 2010). In general, evidence of psychiatric conditions has been viewed by courts as being relevant to civil cases for several reasons including to prove causation, to impeach character witnesses, and to show propensities, or repeated behaviors, that might favor the defendant (Smith, 2010). Indeed, a litigant's mental health history can be an effective tool used to persuade triers of fact. The problem, however, according to Smith (2010) lies within the judicial system; courts, despite admitting a party's relevant psychiatric evidence, frequently misapply or fail to investigate the evidence, which inadvertently results in rulings that do not take into account all of the facts. This combination of introducing and misinterpreting psychiatric evidence during trials, especially with respect to personality disorders, has been described as a ‘danger’ (Smith, 2010, p. 813) in that legal error may result. Thus, it is apparent that the communication channels between courts and mental health professionals need to be vastly improved.

Rationale

The current research suggests that individuals with personality disorders are likely to be litigants in courtroom proceedings. It has been demonstrated in the literature that many defendants who face legal problems also have personality disorders. However, no research to date has focused on reviewing case law to analyze any trends concerning Cluster B personality disorders.

Personality disorders are chronic and pervasive conditions that disrupt the individual's social and occupational relationships throughout the entirety of the lifespan (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). It has been estimated that up to 10% of the population meets criteria for any personality disorder (American Psychiatric Association, 2013); prevalence for Cluster B personalities increase to more than 50% in psychiatric outpatient samples (El Kissi, Ayachi, Ben Nasr, & Bechir Ben Hadj, 2009) and well over 70% in jail or prison (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Personality disorders are prevalent in the judicial system with Cluster B personalities showing up frequently in criminal and correctional settings as well as family court involving child custody disputes (Feinberg & Greene, 1997; Reid, 2009). Given the chronicity, severity and lack of treatment options available for personality disorders, individuals who have personality disorders may be more litigious, overrepresented in certain areas of the law (e.g. criminal), and not as successful on the merits of their cases. Expanding research in this area would better inform the judicial system, courts and lawyers on how to treat evidence of a personality disorder and on the likely outcomes of cases involving personality disorders as well as assist mental health professionals if they were to professionally consult on such a case during the course of a legal proceeding.

Method

Purpose

The purpose of this study was to evaluate Cluster B personality disorders in published United States federal and state case law. Specifically, the researchers conducted an exploratory analysis looking at reasons why litigants would introduce evidence of a Cluster B personality disorder.

Sampling

The sample was estimated to be composed of approximately 1,000 preexisting United States federal and state cases retrieved through the public electronic legal research database LexisNexis. The sample consisted of litigants, either plaintiff or defendant, who have introduced evidence of a Cluster B personality disorder. The sample of litigants within the cases were inclusive of all genders and minorities. Only cases that have been published were included. Cases that were published but have since been depublished were excluded. Likewise, cases that were unreported were excluded. Duplicate cases including appeals were removed from the sample. When possible, the ruling from the highest court on the substantive issue was recorded to provide an accurate representation of the final disposition of the case. The quantitative portion of this study used all cases decided between January 1980, the publication year of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders–Third Edition (DSM–III), and 2016, the date that data collection on this study began. Data were estimated to span 36 years of case law.

Measures

The researchers collected qualitative data using the publicly available, commonly used legal research database LexisNexis. The search terms used were: “diagnos! AND ‘antisocial personality disorder’ w/p dr. OR therapist” wherein ‘antisocial’ was later replaced with borderline, narcissistic and histrionic to collect search results for each of the four Cluster B disorders.

Results

Descriptive analyses

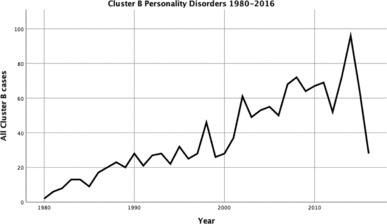

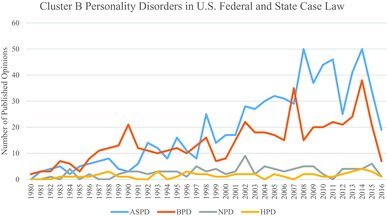

The number of Cluster B cases retrieved from search results was 4,388, of which 2,989 were excluded for a total n = 1,399. In all, there were 718 (51.3%) ASPD cases, 527 (37.7%) BPD cases, 102 (7.3%) NPD cases, and 52 (3.7%) HPD cases. Published federal and state cases spanned from 1980 to 2016. An overall positive trend showing an increase in published opinions referencing a Cluster B personality disorder can be seen in Figure 1. Regarding frequency of cases throughout the years, the fewest number of cases (2) were published in 1980, and the highest number of cases (96) to date peaked in 2014. See Figure 2 for more detail by each disorder. Almost half (46.6%) of the cases were published in the last 10 years.

Figure 1.

Combined Cluster B personality disorders trend in U.S. case law since Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders–Third Edition (DSM–III).9.

Figure 2.

Number of annual opinions by Cluster B litigant. ASPD = antisocial personality disorder; BPD = borderline personality disorder; NPD = narcissistic personality disorder; HPD = histrionic personality disorder. To view this figure in color, please visit the online issue of the Journal.

Most cases were decided by state courts and involved civil5. (68.0%) matters. The majority of all Cluster B litigants were plaintiffs6. (59.3%). More than half (53.7%) of the parties introducing evidence of a Cluster B personality disorder were plaintiffs, 45.2% were defendants, and approximately 1% were court appointed, independent of either party, or unknown. Evidence of a Cluster B disorder tended to be entered into evidence by the opposing party rather than the Cluster B litigant themselves. See Table 1.

Table 1.

Party who introduced evidence of a Cluster B in trial.

| Antisocial |

Borderline |

Narcissistic |

Histrionic |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | % | Total | % | Total | % | Total | % | |

| PD party | 287 | 40.0 | 320 | 60.7 | 34 | 33.3 | 24 | 46.2 |

| Opposing party | 427 | 59.5 | 197 | 37.4 | 65 | 63.7 | 27 | 51.9 |

| Court appointed | 4 | 0.6 | 10 | 1.9 | 3 | 2.9 | 1 | 1.9 |

Note: PD = personality disorder.

Issues presented in cases ranged from federal constitutional appeals to personal injury claims. See Table 2 showing the types and number of cases found. Specifically, the most common types of issues presented in court included criminal appeals (47.9%), disability (19.2%), civil/involuntary commitment (16.7%), and family matters (10.2%). As a group, Cluster B litigants were typically not successful (68.4%) in their legal proceedings. See Table 3 for a complete breakdown of the success of each Cluster B personality disorder.

Table 2.

Types of cases in this sample by Cluster B personality disorder.

| Antisocial | Borderline | Narcissistic | Histrionic | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Criminal appeal | 391 | 233 | 39 | 7 | 670 |

| Civil commitment | 200 | 23 | 11 | – | 234 |

| Disability/benefits | 80 | 161 | 10 | 22 | 273 |

| Family | 30 | 78 | 18 | 17 | 143 |

| Torts | 4 | 18 | 5 | 6 | 33 |

| Civil rights | 12 | 7 | 2 | – | 21 |

| Labor & employment | – | 2 | 15 | – | 17 |

| Education | 1 | 2 | 1 | – | 4 |

| Insurance | – | 2 | – | – | 2 |

| Bankruptcy | – | 1 | 1 | – | 2 |

| Total | 718 | 527 | 102 | 52 | 1,399 |

Table 3.

Litigation success of Cluster B personality disorder parties in published court opinions.

| Successful |

Unsuccessful |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Personality disorder | N | % | N | % |

| Antisocial | 194 | 27.0 | 524 | 73.0 |

| Borderline | 209 | 39.7 | 318 | 60.3 |

| Narcissistic | 19 | 18.6 | 83 | 81.4 |

| Histrionic | 20 | 38.5 | 32 | 61.5 |

| Total | 442 | 31.6 | 957 | 68.4 |

Cluster B data by personality disorder

Antisocial Personality Disorder

The majority of Cluster B cases fell under ASPD with a total of 2,048, of which 1,330 were ruled out; 1,008 were unreported,7. 137 involved parties with no diagnosis8. of ASPD, 76 were overruled, 57 were duplicate cases, 49 were unpublished, and 3 were inapplicable. A net total of 718 valid ASPD cases remained. Of the 718 cases, most (66%) were made up of civil matters; however, more than two thirds of all ASPD cases involved litigants with a criminal history who petitioned the court for matters that fell under the purview of civil law (e.g. habeas corpus petitions, civil commitment). The most common types of cases involving an ASPD litigant were criminal appeals (54.5%) including habeas corpus and postconviction petitions, civil commitment appeals (27.9%) arising out of sexually violent predator or sexually dangerous person (SVP/SDP) state statutes, and disability (11.0%). See Table 2.

In habeas corpus and postconviction petitions, ASPD plaintiffs often used the diagnosis as part of a defense strategy (e.g. competency, diminished capacity, insanity, guilty but mentally ill) against their convictions or in an attempt to mitigate sentencing in instances where they received lengthy sentences and/or capital punishment. A total of 154 out of the 391 ASPD litigants who made a criminal appeal raised the constitutional criminal procedure issue of receiving ineffective assistance of counsel at their original trials. In SVP/SDP cases, ASPD plaintiffs tended to have evidence of an ASPD diagnosis entered against them by the state. This was also the case for family law decisions involving parental termination; state agencies advocating for termination of parental rights introduced evidence of the parent's psychological evaluation showing diagnosis of ASPD.

Regarding the make-up of litigants, 57.4% of the plaintiffs or appellants and 42.6% of the defendants or appellees were diagnosed with ASPD. Forty percent (287) of the ASPD litigants introduced evidence of their personality disorder at trial, and 59.5% (427) had evidence introduced against them by the other party. ASPD litigants tended to be unsuccessful in their cases with an overall success rate of 26.9%. See Table 3.

Borderline Personality Disorder

A search of BPD yielded the second-highest number of cases with 1,865 results retrieved from search engines. Of that amount, 1,338 were excluded; 1,165 were unreported, 107 included no BPD diagnosis, 51 were overruled, 13 were duplicate cases, and 2 were unpublished, which left a total of 527 BPD cases. BPD cases made up 37.7% of the Cluster B cases found, and most (67.9%) were classified as civil lawsuits. The most common types of issues raised in BPD cases were criminal appeals (44.2%), disability (29.8%), and family (14.8%). Similar to ASPD litigants, BPD litigants tended to introduce evidence of their Cluster B personality disorder in mitigation for criminal appeals. For disability cases, BPD was often introduced by the Social Security Administration (SSA) Commissioner or administrative law judge (ALJ) to rebut the Cluster B litigant's claim of disability. In family cases, BPD was commonly introduced by state agencies against parent-petitioners and used to bolster states’ cases in parental termination proceedings.

Most of the BPD cases (64.5%) involved a plaintiff or appellant diagnosed with BPD. The remaining 35.5% involved cases where the defendant or appellee was diagnosed with BPD. Most BPD litigants (60.7%) introduced evidence of their own diagnosis while the remaining had their diagnosis offered by the opposing party. Overall, the majority of BPD litigants (60.3%) tended to be unsuccessful in their cases.

Narcissistic Personality Disorder

A search of NPD cases returned a total of 304, of which 140 were unreported, 35 involved no diagnosis of NPD, 11 were overruled, 11 were duplicate, and 5 were unpublished for a net total of 102 cases. NPD cases tended to fall under civil law (71.6%). The most common cases for NPD litigants in this sample were criminal appeals (36.3%), family (17.6%), and labor and employment (14.7%). The reasons for introducing NPD in criminal and family cases were similar to those provided under ASPD and BPD (e.g. defense, mitigation, parental termination). In labor and employment cases, NPD was commonly diagnosed in the party who was an employee or held a state license (e.g. attorney bar membership, physician license to practice medicine). NPD was entered into evidence in part to provide a rationale as to why the employee was terminated or stripped of their license.

Litigants diagnosed with NPD tended to be defendants (57.8%) more so than plaintiffs. The majority of cases (63.7%) showed that opposing parties usually introduced evidence of the NPD litigant's Cluster B diagnosis. NPD litigants had the least successful rate in cases of the Cluster B disorders with only 18.6% of the rulings made in favor of the NPD litigant.

Histrionic Personality Disorder

HPD cases constituted the fewest number of results in this sample. Search results produced a total of 171 cases, of which 86 were unreported, 25 involved no diagnosis with HPD, 6 were unpublished, 1 was overruled, and 1 was a duplicate. In all, there was a total of 52 valid HPD cases. The majority of HPD cases were classified under civil law (90.4%), the highest percentage of civil to criminal law out of all the Cluster B disorders. The most common cases for HPD litigants to be engaged in were disability (42.3%) and family law (32.7%).

The majority (65.4%) of HPD litigants were plaintiffs. Cases involving an HPD litigant introducing evidence of the Cluster B personality disorder showed that HPD litigants introduced the disorder 34.6% of the time while opposing parties introduced it 63.5%. HPD litigants tended to be less successful in their legal proceedings, achieving a 38.5% success rate on their cases.

Discussion

General Findings

Trend of Cluster B Personality Disorders in United States Case Law

Perhaps one of the more significant findings of this project was the trend of an increasing number of legal decisions involving Cluster B personality disorders since the introduction of the DSM–III in 1980. As seen in Figure 1, there has been a steady overall growth in mentions of Cluster B personality disorders within United States case law and specifically with respect to ASPD and BPD. See Figure 2 for a more detailed view of each personality disorder. Because more than half of the cases in the 36-year span (1980–2016) were published within the last 10 years, one explanation for this increase could be the United States Supreme Court's landmark decision Atkins v VA, 536 U.S. 304 in 2002, which catalyzed the use of mental health as a mitigating factor in criminal sentencing. This finding was consistent with the Douds et al. (2012) study, which showed an increase in FAS cases post Atkins.

Although Atkins (2002) is more commonly known for its use of ID as a defense, Atkins was also an important development in the personality disorder arena. Following Atkins’ own expert Dr. Nelson in the second sentencing phase, the state's forensic psychology expert Dr. Samenow testified in rebuttal that Atkins was in fact of ‘average intelligence, at least’ and diagnosed him with ASPD, a disorder that would not have entitled him to mitigation (Atkins v. VA, at 343, 2002). Though the Virginia Supreme Court's affirmation of Atkins’ convictions and death sentence were later overturned, and Atkins was deemed to be an offender with ID, the introduction of ASPD into testimony was significant. Dr. Samenow, as the state's expert, used ASPD in effect as ammunition against Atkins to explain his criminal behavior and advocate for his penalty. Because Atkins (2002) was a landmark United States Supreme Court decision and served as a blueprint for criminal defense lawyers representing similar defendants throughout the country, it may be more than coincidental that personality disorders such as ASPD multiplied within case law in the years since the Atkins (2002) decision.

Post Atkins (2002), further case law has strengthened the position that personality disorders carry weight in the courtroom. One such example is another United States Supreme Court case, Brumfield v. Cain, 135 S. Ct. 2269 (2015). In Brumfield (2015), plaintiff Brumfield shot and killed a veteran female police officer who was helping guard a grocery store manager on her way to the bank. Brumfield was convicted of the officer's 1993 murder and was sentenced to death (Brumfield v. Cain, 2015). Following the Atkins (2002) decision, Brumfield submitted evidence that his score of ‘75 on an IQ test’ was consistent with the Atkins standard of ID; however, the state rebutted Brumfield's claim of ID using testimony from state psychologist Dr. Bolter who had diagnosed Brumfield with ASPD (Brumfield v Cain, 2015). In the Supreme Court ruling, Justice Sotomayor writing for the majority reasoned that a diagnosis of ASPD did not preclude a defendant from relief under Atkins because ‘antisocial personality is not inconsistent with any of the above-mentioned areas of adaptive impairment, or with intellectual disability more generally’ (Brumfield v Cain, 2015, at 2280). Thus, it is possible that Atkins (2002) and Brumfield (2015) may usher in a new era of litigants who assert a Cluster B personality disorder, the peak of which we have yet to see in case law.

However, the appearance of Atkins (2002) in the legal landscape does not necessarily explain the relatively flat number of cases involving NPD and HPD clients. Of course, there may be other reasons besides Atkins (2002) for the rise in ASPD and BPD cases and the plateau of NPD and HPD cases. One such possibility is that the growth of ASPD and BPD in case law mirrors the growth seen in the empirical literature where much of the research has been focused on those two particular disorders. Both ASPD and BPD enjoy popularity within empirical research and pop culture (see e.g. the televised trials of Jodi Arias, Casey Anthony and Jeffrey Dahmer; the documentary Serial Killer Culture, 2014, which showcases fandom and obsession of notorious offenders), although ASPD is by far more well known and is even considered a ‘sexy’ topic compared to the other Cluster B disorders.

An additional point about the prevalence of ASPD and BPD in this sample as well as in the empirical literature is the attention or notoriety these disorders receive in the media. As evidenced by this research, the majority of ASPD and BPD cases (as well as the majority of all the Cluster B cases found) involved criminal appeals for litigants convicted of murder. Alleged and convicted murderers tend to receive an abundance of air time when crimes happen, especially if the details of the offense are unusually cruel or unique. This presence in the media helps to elevate the status of any personality disorders that are later diagnosed, which thereby can help to popularize the disorder. As interest in a particular disorder, such as ASPD, grows, publishers or producers of media who want to take advantage of the cause célébre encourage the production of features, books and articles of the disorder, which in turn can influence the United States judicial system.

One last possible reason for the acceleration in ASPD and BPD cases is, of course, the increased awareness of trial counsel to issues related to mental health. Criminal defense lawyers are taught in continuing education courses to have their clients ‘shrunk,’ or evaluated by a mental health professional, as part of the discovery process to find out whether any of their client's mental health background can be used as part of a larger narrative in defense strategy. For noncriminal lawyers, continuing education typically includes curriculum on how depression and substance abuse can affect individuals, including lawyers themselves. As lawyers become more aware of problems affecting mental health, it becomes less surprising to see that mental health diagnoses are introduced as evidence at trial. Competence, for example, is such a significant issue to the legal process that competency can be raised sua sponte if the presiding judge suspects that the litigant may have competency-related issues. The psycho-education of lawyers in mental health issues may very well have contributed to a larger awareness of how psychology interacts with the judicial system, and this awareness may have translated into an increase in mental health testimony in court.

Thus, the publication of Atkins (2002), heightened media coverage of notorious criminal defendants, and/or increased awareness of mental health issues on the part of prosecutors and criminal defense attorneys may have contributed to a positive trend of Cluster B in case law since the publication of the DSM–III.

Exploratory Analysis

Parole and Probation

Typically, criminal appellants who petitioned for sentence appeals asked the court to vacate their convictions entirely rather than request alternate sentencing such as parole or probation. The reasoning behind seeking the conviction be overturned completely versus asking for sentence mitigation may have more to do with the convictions themselves; Cluster B litigants as a group tended to be charged with violent crimes. Murder was the most common conviction in the criminal litigant sample. Murder, of course, is a felony requiring imprisonment of more than 365 days, and offenders convicted of murder are oftentimes handed down decades of imprisonment to be served in state penitentiaries. These offenders may not be eligible for parole or probation for many years to come; however, they become immediately eligible to appeal their convictions once sentenced. Thus, the paucity of direct appeals from parole or probation boards could be explained by criminal offenders’ preference to initiate the appeals process as soon as possible. Further, appeals on convictions are independent from appeals they could bring against parole or probation boards in the future, making it possible for a criminal offender to be in the process of appealing their criminal convictions at the same time as initiating an appeal stemming from a parole board decision. Accordingly, few cases found in the sample involved direct appeals of parole or probation board decisions.

Insanity Defense

Depending on the jurisdiction, Cluster B litigants argued for not guilty by reason of insanity (NGRI), guilty but mentally ill (GBMI), and diminished capacity. Overall, Cluster B litigants who argued the insanity defense were unsuccessful on their appeals;10. see Davis v Norris, 423 F 3d 868 (2005) (denying insanity defense and habeas corpus petition to ASPD litigant sentenced to death for murder); US v Waagner, 319 F3d 962 (2003) (denying insanity defense and affirming ASPD litigant's convictions for possession of a firearm, stolen vehicle, and escape); People v Weaver, 26 Cal 4th 876 (2001) (denying insanity defense and affirming convictions for first-degree murder and kidnapping); Davis v State, 595 NW 2d 520 (1999) (affirming convictions for first- and second-degree murder after two experts opined ASPD plaintiff was not legally sane when he committed the killings); State v Young, 780 P 2d 1233 (1989) (dismissing ASPD litigant's diminished capacity claim and affirming convictions of kidnapping, sexual assault and robbery); State v Murphy, 872 P 2d 480 (1994) (denying ASPD litigant's GBMI defense while affirming a conviction for sexual abuse of a child); and State v Rainey, 580 A 2d 682 (1990) (denying BPD litigant's ‘abnormal condition of the mind’ defense and affirming convictions for the intentional or knowing murder of his stepdaughter and fiancé and attempted murder of stepson).

Of the few cases in which Cluster B litigants were successful in arguing for insanity, there were some common aspects. For one, these cases involved litigants who were diagnosed with either ASPD or BPD; no NPD litigant was successful in arguing for insanity, and there were no insanity cases in this sample involving an HPD litigant. Second, ASPD and BPD litigants who successfully argued insanity tended to be criminal defendants convicted of a violent offense such as murder and, upon a successful appeal, had their cases reversed and were remanded to trial court for further consideration of their insanity claims.

It is quite possible that one of the reasons why some ASPD and BPD litigants succeeded on their insanity defenses was that they were able to show a nexus between their personality disorder symptoms and their claim for insanity. Out of the four Cluster B personality disorders, ASPD and BPD are the two disorders listing criteria that effortlessly lend themselves to an insanity claim. Specifically, DSM–5 (2013) ASPD criteria A3 for impulsivity and A4 for irritability and aggressiveness, especially when coupled with high comorbidity of substance use, correspond to a likelihood for ‘blacking out’ during violent incidents. Similarly, DSM–5 BPD criterion A9 describing ‘transient, stress-related paranoid ideation or severe dissociative symptoms’ could be argued as an insanity claim based on the likelihood that an offender may slip in and out of reality during a violent crime. When contrasted with NPD and HPD, both of which omit criteria pertinent to insanity (such as impulsivity and dissociation) and garner attention from others in a much different fashion than what is found in ASPD and BPD, it becomes more understandable that the former two disorders tend to be unsuccessful or altogether absent from insanity cases.

Capital punishment

Criminal appellants who petitioned for death sentence appeals had similar characteristics. They tended to be male plaintiffs diagnosed with ASPD who appealed their sentences through habeas corpus or postconviction petitions. Violent crimes including first-degree murder, rape and robbery were typical of the convictions found with these plaintiffs. Both state expert and defense counsel witnesses presented evidence of criminal appellants’ Cluster B personality disorders; in general, the state presented evidence of the personality disorder to help convict the Cluster B litigant and to persuade the jury as to why they should be sentenced to death. Cluster B litigants also presented evidence of their own diagnoses in mitigation.

One apparent theme in the sample was that Cluster B diagnoses such as ASPD were considered to be more of an aggravating, rather than mitigating, factor in capital punishment sentencing. For the most part, Cluster B diagnoses were used in this sample more as a sword than as a shield; see e.g. Stewart v Sec'y, 476 F 3d 1193 (2007) (affirming denial of ASPD plaintiff's habeas corpus petition); Bible v Schriro, 497 F Supp.2d 991 (2007) (denying ASPD plaintiff's habeas corpus petition and vacating stay of execution previously awarded by lower court); Lorraine v Coyle, 291 F 3d 416 (2002) (reversing grant of ASPD plaintiff's habeas petition); Worthington v Roper, 631 F.3d 487 (2011) (reversing federal court grant of writ of habeas to ASPD plaintiff); and Cullen v Pinholster, 563 US 170 (2011) (US Supreme Court case reversing lower federal court grant of writ of habeas to ASPD plaintiff).

One emerging theme in this sample regarding successful appeals for capital punishment sentences was where the Cluster B litigants themselves presented evidence of their own diagnosis. Rather than have the opposing party introduce the Cluster B diagnosis, criminal litigants facing death sentences offered evidence of their ASPD or BPD.11. This discovery was atypical of the overall data found in that most litigants tended to have their Cluster B diagnoses introduced by the opposing party. Perhaps when faced with capital punishment, Cluster B litigants viewed their diagnoses through the lens of the dicta in Gregg v GA, 428 US 513 (1976)12. and the ‘death is different’ doctrine. It is quite possible that with their own mortality looming, these litigants were forthright in their habeas corpus and postconviction petitions in a way that they had not been in previous proceedings, perhaps even in their own original criminal trials. Some litigants were rewarded for their efforts by having their convictions or sentences vacated, which should serve as inspiration for any litigant to explore all avenues when it comes to capital punishment defense.

Parental Rights Termination

Parental rights termination proceedings comprised the majority of family law cases in this sample. In general, Cluster B personality disorders were treated negatively in case law and were solely used to support the termination of parental rights. No Cluster B litigant in a parental termination case used evidence of their Cluster B diagnosis as a positive trait with regards to parenting. In fact, Cluster B diagnoses were typically admitted into evidence only after the state ordered a psychological evaluation for the parent to determine parental fitness. The most common Cluster B diagnosis in parental termination proceedings was BPD, which is understandable given the pathological relational model inherent in BPD individuals, the need for closeness to others and the volatility that comes with splitting. Evidence of a Cluster B disorder tended to be introduced on behalf of mothers more than fathers, but this could have been because more mothers appealed their parental rights termination decisions and subsequently had their case/diagnosis published in a court opinion.

Cluster B litigants were predominantly unsuccessful in their parental rights termination appeals. This was especially apparent in cases where the mother threatened to or actually harmed herself in front of her children; see In the Matter of LGT (State v RJT), 229 Ore App. 619 (2009) (affirming parental termination of a young adopted child after BPD mother had attempted suicide at least five times during the child's life); TN v Bates, 84 S.W.3d 186 (2002) (affirming parental termination after BPD mother attempted suicide at home using a gas stove while her children were present); and In the Interest of TLB, 376 SW 3d 1 (2011) (affirming parental termination after BPD mother made threats to commit suicide and murder all of the children).

Courts also severed the parent–child relationship in cases where it appeared that termination was in the best interests of the child; see In re Carrington H, 483 SW 3d 507 (2015) (affirming termination of HPD parent after finding that it was in the best interest of the child); In the Interest of TMS, 242 Ga App 442 (2000) (affirming the juvenile court's decision in favor of termination due to parental misconduct or inability); In re JW, 779 NE 2d 954 (2002) (affirming termination after HPD mother who was also diagnosed with Munchausen by proxy and ASPD purposely gave her infant multiple prescription drugs); In the Matter of Aniya L, 124 AD 3d 1001 (2015) (affirming that termination of BPD mother rights was in the best interest of the child); and In the Matter of Lehtonen (State v Lehtonen), 172 Ore App 584 (2001) (affirming termination of BPD mother's parental rights after finding that mother's condition was detrimental to the child and that termination was in the best interests of the child).

Civil Litigant Success

The majority of cases analyzed for civil litigant success were composed of supplemental security income (SSI)/disability cases. Cluster B litigants tended to be the parties appealing termination of benefit decisions or benefit denials; few of the cases found involved the SSA Commissioner appealing decisions in favor of the Cluster B appellant. Mental health professionals, specifically psychologists and psychiatrists, were instrumental in SSI/disability decisions, and the SSA appeared to base their decisions entirely on consulting professionals who performed evaluations on behalf of the government.

Generally, Cluster B litigants who showed evidence of physical symptoms and serious diagnoses in addition to their Cluster B diagnosis met the definition of disability; see, for example, Delgado v Colvin, 190 Soc Sec Rep Service 644 (1986) (reversed and remanded SSI denial for an HPD plaintiff who was diagnosed with cerebral palsy, depression, bipolar disorder and back problems); Griffin v Astrue, 167 Soc Sec Rep Service 730 (2011) (granted in part and remanded for HPD plaintiff who alleged disability due to bipolar disorder, auditory hallucinations and panic attacks); Chase v Astrue, 158 Soc Sec Rep Service 411 (2010) (reversed and remanded denial for HPD plaintiff who was diagnosed with migraines, depression, anxiety, agoraphobia, hearing loss, tinnitus, PTSD, nerve damage, memory loss, neck/shoulder pain, effects of a head injury); Green v. Barnhart, 262 F Supp 2d 1271 (2003) (reversed and remanded for HPD plaintiff who was unable to work and alleged chronic fatigue syndrome, fibromyalgia, ADHD, bladder incontinence, depression, somatoform disorder, and possible sleep apnea); and Schneider v Apfel, 74 Soc Sec Rep Service 234 (2001) (remanded for calculation of benefits for HPD plaintiff who had chemical sensitivity; Raynaud's disease; depression; anxiety; posttraumatic stress disorder, PTSD; panic attacks; psychosomatic symptoms; fibromyalgia; a learning disorder; and carpal tunnel syndrome).

Though all of the Cluster B personality disorders were represented in SSI/disability cases, BPD and HPD were prevalent. These two disorders correspond in the literature to a more hysterical presentation, the symptoms of which may be somaticized when compared to individuals with ASPD and NPD. Further, individuals with BPD or HPD may be more likely to seek out disability compensation in part due to a sense of urgency that may exaggerate physical symptoms, due to a desire for validation of their pain and psychic injury, for attention-seeking purposes (especially if the litigant is female and internalized an unstable view of the self that requires rescuing from an external source), or because of an overwhelming feeling of incompetence after experiencing years of living in an invalidating social environment. Of course, there is also the possibility that BPD and HPD were overdiagnosed in this sample given the gender bias for both disorders to be diagnosed more in female patients. This may readily have been the case given that many of the SSI/disability cases found dated back to the 1980s in a time where cultural competence in gender bias was not as fully developed as it is today.

Limitations

There are several limitations in our research. First, excluding unpublished and unreported case opinions may have affected the overall results of this sample. Out of thousands of court opinions rendered each day, a very small percentage of those are published. Many relevant and significant opinions concerning this research may have been unreported, depublished, or never published in the first place. Using a sample that only reviews published court opinions may have significantly reduced the volume of relevant cases through which to gain an understanding of Cluster B personality disorders in case law.

A second limitation was internal validity in categorizing collected data. Legal opinions tend to be complex and include multiple, confounding variables that make it difficult to sort out decisions. Many times, decisions in this sample of case opinions did not hinge upon a Cluster B personality disorder diagnosis at all but rather on a procedural issue. A litigant's personality disorder was just one variable in a broader narrative of evidence, which at times made it difficult to collect data and could have resulted in errors.

Another limitation in this research was that it involved reviewing appellate decisions instead of trial court transcripts. Because this study collected data using published opinions, cases that had achieved a publication status had, in some cases, been appealed dozens of times. Restating the same facts throughout multiple opinions could have resulted in errors and/or misinterpretations despite the courts’ due diligence in maintaining accuracy. Reviewing the trial court transcript, had they been available for all of the cases in this sample, might have resulted in greater accuracy or less misinterpretation of facts.

Conclusion

Research on Cluster B personality disorders in United States case law is a new frontier. This study took an initial step in showing that court opinions and legal history can provide clues as to litigants’ psychological make-up and offer insight into an overall broader scheme of how personality can affect trial outcomes. All too often in the past, individuals who were diagnosed with what was once called an ‘Axis Two’ were thought of as unmanageable. This stigmatizing effect unfortunately found its way through the legal system such that attorneys were cautioned before undertaking cases involving an individual with a personality disorder. Equipped with little empirical research on personality disorders and their legal implications, some counsel may be at a loss with how to strategize effectively for a Cluster B litigant. As attorneys struggle to present these clients in a favorable light within the courtroom, they may not realize the value in past years of case law involving a Cluster B party. With continued research utilizing both mental health professionals and legal experts, a more nuanced understanding of Cluster B litigants can take shape and conceivably transform the way these litigant-patients are seen in and outside of the courtroom.

Notes

Atkins v. VA, 536 U.S. 304 (2002) (establishing that imposing capital punishment on ‘mentally retarded’ individuals constituted excessive punishment and violated the 8th Amendment).

Arkansas, Iowa, Minnesota, Missouri, Nebraska, North Dakota, South Dakota.

Alaska, Arizona, California, Hawaii, Idaho, Montana, Nevada, Oregon, Washington, Guam, Northern Mariana Islands.

466 US 668 (1984) (holding that a criminal defendant's Sixth Amendment right to counsel is violated when counsel renders ineffective assistance).

Appeals stemming from criminal conduct involving constitutional rights issues (e.g. habeas corpus petitions) were categorized as civil based upon the area of law they would likely fall under.

Most litigants diagnosed with a Cluster B personality disorder were categorized as plaintiffs or appellants because they were often the parties appealing earlier decisions. This means that the majority of these Cluster B litigants were defendants in their original trials. Because published case opinions tend to be appellate in nature, the cases that were reviewed reflected the Cluster B litigant as the plaintiff/appellant/petitioner but may not necessarily mean that depiction was true in earlier proceedings. In sum, despite what role Cluster B litigants appeared to play in this sample, it is more likely that they would be on the receiving end of a lawsuit.

Unreported cases are cases that are not published in hard copy reporter series. Similar to unpublished cases, unreported cases were excluded from this study.

These cases mentioned the diagnosis in a parenthetical citation to an earlier case or described testimony in which the litigant was said to have “features” or “traits” of the disorder rather than the diagnosis; accordingly, these cases were omitted. The same is true of the remaining three Cluster B personality disorders where no diagnosis was found in the opinion.

Note: 2016 data were incomplete as of data collection in this study.

Interestingly, John Hinckley, who successfully argued his insanity case after he gained notoriety for stalking Jodie Foster and the attempted assassination of President Ronald Reagan, appeared in this sample's search results due to his lengthy history of carrying an NPD diagnosis; however, his appeal at US v Hinckley, 40 F Supp 3d 8 (2013) was concerned with the issue of his conditional release from St. Elizabeth's Hospital where he had been held for the last 30 years rather than his insanity plea.

There were no successful capital punishment cases in this sample with an NPD or HPD party.

Landmark decision holding that the death penalty did not violate the U.S. Constitution's 8th and 14th Amendments.

Ethical standards

Declaration of conflicts of interest

Catherine Young has declared no conflicts of interest

Janice Habarth has declared no conflicts of interest

Bruce Bongar has declared no conflicts of interest

Wendy Packman has declared no conflicts of interest

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

References

- American Psychiatric Association (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Washington, DC: Author. [Google Scholar]

- Appelbaum P. S., & Greer A. (1994). Who's on trial? Multiple personalities and the insanity defense. Hospital & Community Psychiatry, 45(10), 965–966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Appelbaum P. S., & Gutheil T. G. (2007). Clinical handbook of psychiatry and the law (4th ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. [Google Scholar]

- Atkins v. Virginia, 536 U.S. 304 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- Blashfield R. K., & Intoccia V. (2000). Growth of the literature on the topic of personality disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry, 157(3), 472–473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coid J. W. (2002). Personality disorders in prisoners and their motivation for dangerous and disruptive behavior. Criminal Behaviour and Mental Health, 12(3), 209–226. doi: doi.org/ 10.1002/cbm.497 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coid J., Yang M., Tyrer P., Roberts A., & Ullrich S. (2006). Prevalence and correlates of personality disorder in Great Britain. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 188(5), 423–431. doi: dx.doi.org/ 10.1192/bjp.188.5.423 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson J. (1999). The alter as agent: Multiple personality and the insanity defence. Psychiatry, Psychology and Law, 6(2), 203–206. [Google Scholar]

- Denno D. W. (2015). The myth of the double-edged sword: An empirical study of neuroscience evidence in criminal cases. Boston College Law Review, 56(2), 493–551. [Google Scholar]

- Douds A. S., Stevens H. R., & Sumner W. E. (2012). Sword or shield? A systematic review of the roles FASD evidence plays in judicial proceedings. Criminal Justice Policy Review, 24(4), 492–509. doi: 10.1177/0887403412447809 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- El Kissi Y., Ayachi M., Ben Nasr S., & Bechir Ben Hadj A. (2009). Personality disorders in a group of psychiatric outpatients: General aspects and Cluster B characteristics. La Tunisie Medicale, 87(10), 685–689. Retrieved from http://www.latunisiemedicale.com/article-medicale-tunisie_1186_en [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feinberg R., & Greene J. T. (1997). The intractable client: Guidelines for working with personality disorders in family law. Family & Conciliation Courts Review, 35(3), 351–364. doi: 10.1111/j.174-1617.1997.tb00476.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Freckelton I. (2013). Autism Spectrum Disorder: Forensic issues and challenges for mental health professionals and courts. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 26(5), 420–434. doi: 10.1111/jar.12036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freckelton I., & List D. (2009). Asperger's Disorder, criminal responsibility and criminal culpability. Psychiatry, Psychology and Law, 16(1), 16–40. doi: 10.1080/13218710902887483 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fusco G. M. (2015). Clinical management: Working with those diagnosed with personality disorders. In Beck A. T., Davis D. D., & Freeman A. (Eds.), Cognitive therapy of personality disorders (3rd ed., pp. 409–427). New York, NY: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gabbard G. O. (1994). Psychodynamic psychiatry in clinical practice (5th ed.). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press. [Google Scholar]

- García-Nieto R., Blasco-Fontecilla H., de Léon-Martinez V., & Baca-García E. (2014). Clinical features associated with suicide attempts versus suicide gestures in an inpatient sample. Archives of Suicide Research, 18(4), 419–431. doi: 10.1080/13811118.2013.845122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman M., Roiff T., Oakes A. H., & Paris J. (2012). Suicidal risk and management in Borderline Personality Disorder. Current Psychiatry Reports, 14(1), 79–85. doi: 10.1007/s11920-011-0249-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregory R. J. (2012). Managing suicide risk in Borderline Personality Disorder. Psychiatric Times, 29(5), 25–26. [Google Scholar]

- Hare R. D., Hart S. D., & Harpur T. J. (1991). Psychopathy and the DSM-IV criteria for Antisocial Personality Disorder. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 100(3), 391–398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatchett G. T. (2015). Treatment guidelines for clients with Antisocial Personality Disorder. Journal of Mental Health Counseling, 37(1), 15–27. [Google Scholar]

- Hodgins S., & Côté G. (1993). Major mental disorder and antisocial personality disorder: A criminal combination.. The Bulletin of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law, 21(2), 155–160. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard R. C., Huband N., Duggan C., & Mannion A. (2008). Exploring the link between personality disorder and criminality in a community sample. Journal of Personality Disorders, 22(6), 589–603. doi: 10.1521/pedi.2008.22.6.589 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James D. (1998). Multiple personality disorder in the courts: A review of the North American experience. The Journal of Forensic Psychiatry, 9(2), 339–361. doi: 10.1080/09585189808402201 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson S. C., & Elbogen E. B. (2013). Personality disorders at the interface of psychiatry and the law: Legal use and clinical classification. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience, 15(2), 203–211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keeney M. M., Festinger D. S., Marlowe D. B., Kirby K. C., & Platt J. J. (1997). Personality disorders and criminal activity among cocaine abusers. In Problems of Drug Dependence 1997: Proceedings of the 59th annual scientific meeting of the college on problems of drug dependence (Research Monograph No. 178). National Institute on Drug Abuse. [Google Scholar]

- Kraus G., & Reynolds D. J. (2001). The “a-b-c's” of the cluster b's: Identifying, understanding, and treating cluster b personality disorders. Clinical Psychology Review, 21(3), 345–373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenzenweger M. F., Lane M. C., Loranger A. W., & Kessler R. C. (2007). DSM-IV personality disorders in the natural comorbidity survey replication. Biological Psychiatry, 62(6), 553–564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis S. F., Fremouw W. J., Del Ben K., & Farr C. (2001). An investigation of the psychological characteristics of stalkers: Empathy, problem-solving, attachment and borderline personality features. Journal of Forensic Sciences, 46(1), 80–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ménard K. S., & Pincus A. L. (2014). Child maltreatment, personality pathology, and stalking victimization among male and female college students. Violence and Victims, 29(2), 300–316. doi: 10.1891/0886-6708.VV-D-12-00098R1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pompili M., Girardi P., Ruberto A., & Tatarelli R. (2005). Suicide in borderline personality disorder: A meta-analysis. Nordic Journal of Psychiatry, 59(5), 319–324. doi: 10.1080/08039480500320025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radwin J. O. (1991). The multiple personality disorder: Has this trendy alibi lost its way? Law & Psychology Review, 15, 351–373. [Google Scholar]

- Reid W. H. (2009). Borderline personality disorder and related traits in forensic psychiatry. Journal of Psychiatric Practice, 15(3), 216–220. doi: 10.1097/01.pra.0000351882.75754.0c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts A. D. L., & Coid J. W. (2010). Personality disorder and offending behavior: Findings from the national survey of male prisoners in England and Wales. The Journal of Forensic Psychiatry & Psychology, 21(2), 221–237. doi: 10.1080/14789940903303811 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sandberg D. A., McNiel D. E., & Binder R. L. (1998). Characteristics of psychiatric inpatients who stalk, threaten, or harass hospital staff after discharge. American Journal of Psychiatry, 155(8), 1102–1105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sansone R. A., & L. A. (2010). Fatal attraction syndrome: Stalking behavior and borderline personality. Psychiatry, 75(5), 42–46. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sansone R. A., & Sansone L. A. (2010). Fatal attraction syndrome: Stalking behavior and borderline personality. Psychiatry (Edgemont), 7(5), 42–46. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sansone R. A., Watts D. A., & Wiederman M. W. (2014). Borderline personality symptomatology and legal charges related to drugs. International Journal of Psychiatry in Clinical Practice, 18(2), 150–152. doi: 10.3109/13651501.2013.847107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon R. I. (1995). Beware the legal liabilities of treating BPD patients. Psychotherapy Letter, 7(6), 2–3. [Google Scholar]

- Sisti D. A., & Caplan A. L. (2012). Accommodation without exculpation? The ethical and legal paradoxes of borderline personality disorder. The Journal of Psychiatry & Law, 40(1), 75–92. doi: doi.org/ 10.1177/009318531204000106 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Smith D. M. (2010). The disordered and discredited plaintiff: Psychiatric evidence in civil litigation. Cardozo Law Review, 31(3), 749–822. [Google Scholar]

- Stone M. H. (1993). Paradoxes in the management of suicidality in borderline patients. American Journal of Psychotherapy, 47(2), 255–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]