Abstract

Symbiotic Rhizobium-legume associations are mediated by exchange of chemical signals that eventually result in the development of a nitrogen-fixing nodule. Such signal interactions are thought to be at the center of the plants’ capacity either to activate a defense response or to suppress the defense response to allow colonization by symbiotic bacteria. In addition, the colonization of plant roots by rhizobacteria activates an induced condition of improved defensive capacity in plants known as induced systemic resistance, based on “defense priming,” which protects unexposed plant tissues from biotic stress.Here, we demonstrate that inoculation of common bean plants with Rhizobium etli resulted in a robust resistance against Pseudomonas syringae pv. phaseolicola. Indeed, inoculation with R. etli was associated with a reduction in the lesion size caused by the pathogen and lower colony forming units compared to mock-inoculated plants. Activation of the induced resistance was associated with an accumulation of the reactive oxygen species superoxide anion (O2 −) and a faster and stronger callose deposition. Transcription of defense related genes in plants treated with R. etli exhibit a pattern that is typical of the priming response. In addition, R. etli–primed plants developed a transgenerational defense memory and could produce offspring that were more resistant to halo blight disease. R. etli is a rhizobacteria that could reduce the proliferation of the virulent strain P. syringae pv. phaseolicola in common bean plants and should be considered as a potentially beneficial and eco-friendly tool in plant disease management.

Keywords: induced systemic resistance, priming, nodule, Rhizobium etli, Pseudomonas

Introduction

Over the last few decades, particularly after the Green Revolution, the global agricultural production increased considerably. However, due to the sustained increase in the global human population, the demand for higher crop production has also increased substantially. Accordingly, to achieve higher agriculture yields, farmers have adopted the extensive application of chemical fertilizers and pesticides, resulting in soil degradation and decrease in soil fertility (Gouda et al., 2018). In addition, nitrous oxide (N2O), which is a by-product of excess nitrogen (N) fertilization, is a chemical pollutant and contributes to global warming as it is the single most important ozone-depleting substance (Ravishankara et al., 2009; Vejan et al., 2016). Also, the excess application of ammonium nitrate in soils leads to a decline in symbiotic interactions established between microbes and legume plants (Vejan et al., 2016). Therefore, reducing the use of synthetic chemical pesticides and fertilizers is one of the challenges in modern society.

Some of the strategies involved in sustainable crop production and integrated pest management include development of novel cultivars exhibiting disease resistance, abiotic stress tolerance, and high nutritional value, application of genetic engineering tools to develop non-legume crops participating in N-fixing symbioses, and the use of biological control agents and plant growth promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR) (Bruce, 2010; Ubertino et al., 2016; Gouda et al., 2018). The use of PGPR is one of the most promising tools for disease management in contemporary agriculture and an alternative that could minimize reliance on agrochemicals (Timmermann et al., 2017). PGPR can be used to promote plant growth and development and enhance plant health without negatively affecting natural ecosystems and biodiversity and without environmental contamination (Calvo et al., 2014; Vejan et al., 2016). With regard to their association with root cells, PGPR could be classified into either intracellular PGPR (iPGPR, symbiotics) or extracellular PGPR (ePGPR, free living) (Martínez-Viveros et al., 2010). iPGPR may inhabit specialized root structures such as root nodules, while ePGPR may be found on root surfaces, in the rhizosphere, or in between root cortex cells (Martínez-Viveros et al., 2010; Gouda et al., 2018).

PGPR have numerous direct or indirect mechanisms for preventing growth and development of pathogens, such as antagonism, competitive exclusion, production of antibiotics, or extracellular secondary metabolites that inhibit pathogen growth, signal interference, competition for nutrients/resources (e.g., fixed N, ferric ion by siderophore production), hormone production, and the activation of the induced systemic resistance (ISR) plant defense system (Haas and Défago, 2005; Glick, 2012; Timmermann et al., 2017).

ISR is defined as an induced condition of enhanced defensive capacity in plants, which is activated in response to biological or chemical stimuli (e.g., colonization of the roots by PGPR or beneficial fungi or treatment with chemical compounds), and protects unexposed plant tissues against pathogenic invasion and insect herbivory (Pieterse et al., 2014; Timmermann et al., 2017; Gouda et al., 2018). ISR aids plants to fight numerous diseases and is effective against a wide range of pathogenic bacteria and fungi, and the activation of the defense mechanisms acts systemically in plant sections that are spatially separated from the inducer (Pieterse et al., 2014).

Activation of ISR by advantageous microorganisms is often based on priming (Pieterse et al., 2014), a physiological state that prepares the plant for a more rapid and/or greater activation of cellular defenses when exposed to biotic or abiotic stress, resulting in an enhanced level of resistance (Conrath, 2009; Conrath, 2011). In 1991, Van Peer and colleagues revealed that priming of defense responses is involved in ISR. In their study, the roots of carnation plants (Dianthus caryophyllus) were “bacterized” (primed) with Pseudomonas sp. strain WCS417r prior to inoculation with the pathogen Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. dianthi. Primed plants (bacterized) showing ISR exhibited enhanced synthesis and accumulation of phytoalexins following inoculation with F. oxysporum, when compared with non-induced control plants (Van Peer et al., 1991). Furthermore, induced resistance against pathogens has been associated with a faster and stronger accumulation of callose (Ton et al., 2005). For example, β-amino-butyric-acid (BABA) induced resistance in Arabidopsis correlates with primed deposition of callose-rich papillae (or enhanced accumulation of callose; Ton and Mauch-Mani, 2004).

Callose-containing cell-wall appositions, named papillae (where antimicrobial compounds can be deposited; Luna et al., 2011), are induce at the sites of pathogen attack, in primed plants, at early stages of pathogen invasion, and could also contribute to disease resistance by strengthening the plant cell wall at the site of pathogen invasion (Kohler et al., 2002).

In Arabidopsis plants primed by ISR (following colonization by PGPR), activation of the induced response involves the activation of the salycilic acid (SA)–, jasmonate (JA)-, and ethylene (ET)-signaling pathways. For example, priming with the PGPR Paraburkholderia phytofirmans PsJN reduces plant susceptibility to disease and the proliferation of the virulent strain Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato DC3000 (PstDC3000) (Timmermann et al., 2017). In addition, P. phytofirmans PsJN induces transcriptional changes in key defense-related genes of the SA-, JA-, and ET-signaling pathways (e.g., PATHOGENESIS RELATED 1, PLANT DEFENSIN 1.2) in plants infected with PstDC3000. Also, the plant hormone abscisic acid (ABA), which regulates numerous plant developmental processes and adaptive responses to stress, has been involved in priming by beneficial microbes for enhanced callose deposition (Ton et al., 2005; Asselbergh et al., 2008; Pieterse et al., 2014). Furthermore, brassinosteroids modulate plant defense responses against pathogens and protect plants from environmental stresses, independently of SA-mediated defense signaling and PR gene expression (Krishna, 2003; Bari and Jones, 2009).

However, the activation of the different hormone-signaling pathway(s) following the application of the ISR-inducing PGPR seems to be specific to the plant species, as well as the pathogen and PGPR involved (De Vleesschauwer and Höfte, 2009; Timmermann et al., 2017). Basic research on the application of PGPR and in the exploitation of existing tools and techniques for safer and productive agricultural practices remains limited (Gouda et al., 2018).

Legume plants, particularly the common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.), are great model systems for studying ISR, as well as defense-priming and plant-pathogen interactions. For instance, common bean interacts with symbiotic diazotrophic bacteria (rhizobia). The symbiotic interaction results in the formation of new plant organs, N-fixing nodules, which fix atmospheric N (Taté et al., 1994). Therefore, symbiotic N-fixing rhizobacteria have positive effects on the host plants, not only facilitating nutrient availability but also priming defense against biotic and abiotic stresses via activation of ISR (Franche et al., 2009; Gouda et al., 2018).

To determine if rhizobacteria elicits the ISR in common bean against P. syringae pv. phaseolicola (PspNPS3121), the causal agent of the halo blight disease, we evaluated the effect of using R. etli to induce resistance based on pathogen accumulation, symptom emergence, nodule number, N fixation, callose deposition, and changes in levels of expression of defense related genes, within and across generations.

Materials and Methods

Plant Material

P. vulgaris cultivar “Rosa de Castilla” (Jiménez-Hernández et al., 2012), a type of bean produced under rainfed conditions and susceptible to the halo blight bacterial disease, was used in the present study. Seeds were surface sterilized (15 min in 2% NaOCl), rinsed three times with sterile deionized water, and germinated under sterile conditions, in moist paper towels, at 28°C. Three days after germination (dag), the seedlings were transferred to 2.3-L pots containing vermiculite, inoculated with 4 ml of the Rhizobium etli CE3 suspension, and placed in a greenhouse (Guanajuato, México, 101°09′01″ W, 20°30′09″ N; 1730 masl; as described by Martínez-Aguilar et al., 2016). The experiments were performed under daylight conditions, with maximum and minimum temperatures of 30 and 18°C, respectively. All inoculated plants were fertilized once a week with a B&D nutrient solution (Broughton and Dilworth, 1971) without N. Non-inoculated plants were fertilized with a B&D solution supplemented with N (8 mM KNO3; Estrada-Navarrete et al., 2007).

Rhizobacteria Growth Conditions and Inoculation

R. etli strain CE3 was grown at 28°C on PY media (5 g/L of peptone, 3 g/L of yeast extract, 0.7 g/L of calcium chloride) supplemented with 20 μg/ml nalidixic acid, 100 mg/ml streptomycin (Cárdenas et al., 2006), and 7 mM CaCl2 until the bacterial culture reached an OD600 of 0.5–0.6. The bacterial culture was centrifuged (5,000 rpm; Sorvall GSA Rotor), the pellets washed in 10 mM MgSO4, and the cells resuspended in 10 mM MgSO4 (Cárdenas et al., 2006). Subsequently, 3-day-old roots from “Rosa de Castilla” cultivar were inoculated, by drench, with 4 ml of the bacterial resuspension.

Pathogen Infection

Pathogen infection in F0 plants was performed as described by Martínez-Aguilar et al., 2016. Briefly, P. syringae pv. phaseolicola NPS3121 (PspNPS3121) was cultivated for 36 h at 28°C on KB media containing 50 μg/ml rifampicin; then, the cells were resuspended in MgCl2 (10 mM) at a final concentration of 5 × 108 colony-forming units per milliliter (CFU/ml). Four milliliters of the bacterial solution were placed in a syringe without a needle, and the abaxial surfaces of the second trifoliate leaves were infiltrated with the pathogen 17 dag. Six infiltration points per leaf were employed. Negative control plants were neither treated nor infiltrated, while positive control plants were not infiltrated but treated with R. etli. To determine the systemic effect, samples were obtained from distal leaves not exposed to the pathogen, 1 day before infection, and 1 and 5 days after infection. Table 1 presents an outline of the experimental design.

Table 1.

Experimental design.

| Treatments | |

|---|---|

| Rhizobium etli (3 dag) | + Phaseolus syringae (17 dag) |

| R. etli (3 dag) | + H2O (17 dag) |

| R. etli (3 dag) | — |

| — | P. syringae (17 dag) |

| — | — |

dag, days after germination.

Disease Evaluation

Bacterial growth was assessed 10 days after infection as follows: three leaf discs adjacent to the infection sites were excised using a 1-cm diameter stainless steel cork borer, then rinsed and homogenized with sterile deionized water, and plated in serial dilutions on KB media containing 50 μg/ml rifampicin and 6 mM MgSO4. The plates were incubated for 36 h at 28°C, and the total numbers of CFUs from three plates for each dilution were counted. The percentage of leaf damage (total chlorotic leaf area/total leaf area) and lesion size (total chlorotic and necrotic leaf area/total leaf area), on leaves that had been exposed to the pathogen, was determined using Fiji software (Schindelin et al., 2012).

Callose Quantification

To determine callose deposition in leaves of common bean plants, we followed the protocol described by Luna et al. (2011) with slight modifications. Seventeen days old P. vulgaris plants (co-cultivated with the symbiont) were immersed, for 30 s, in a bacterial solution (MgCl2 10 mM, Silwet L-77 0.05%, and PspNPS3121 at a concentration of 5 × 108 CFU/ml). After 24 h of pathogen infection, the plants were destained for 24 h in 95% ethanol, washed in 0.07 M phosphate buffer (pH 9), and incubated for 24 h in 0.07 M phosphate buffer containing 0.01% aniline blue (Sigma–Aldrich, catalog #415049). Imaging of callose deposition in three plants per treatment, from two leaves per plant (and four discs per leaf, with a diameter of 1 cm each), was performed with an Olympus BX50 microscope (UV filter BP 340–380 nm, LP 425 nm), and pictures were taken with a Lumenera INFINITY 3 camera. Quantification and callose intensity were determined by using the Fiji software (https://imagej.net) and following the protocol described by Jin and Mackey (2017).

Histochemical Detection of Superoxide Radical

To detect the accumulation of the superoxide anion (O2 −), a reactive oxygen species, we followed the protocol described by Timmermann et al. (2017) with some modifications. Aerial parts of 17 days old P. vulgaris plants (co-cultivated with the symbiont) were immersed, for 30 s, in a bacterial solution (MgCl2 10 mM, silwett L-77 0.05%, and PspNPS3121 at a concentration of 5 × 108 CFU/ml). After pathogen infection (24 h), leaves were removed from plants at 1.5, 3, 6, and 9 h and incubated for 24 h at room temperature in a phosphate buffered saline solution (137 mM NaCl; 2.7 mM KCl; 10 mM Na2HPO4; 2 mM KH2PO4) containing 0.06 mM nitroblue tetrazolium (Sigma–Aldrich, catalog # N6639). The leaves were then cleared in 80% ethanol (50 ml) at 60°C to extract chlorophylls (Timmermann et al., 2017). Imaging of purple formazan deposits (visualized as a blue precipitate), which result from the reaction of nitroblue tetrazolium with O2 − (Carvalho et al., 2008), identified the areas where O2 − was accumulated. Images were taken using a digital camera Nikon 5500 (Nikon Corp., Tokyo, Japan). Quantification of O2 was performed using the protocol described by Juszczak and Baier, 2014. Each experiment was independently performed in triplicate.

Acetylene Reduction Assay

Acetylene reduction assays were performed using whole nodulated roots 24 days post-inoculation (dpi) according to Barraza et al. (2018). Each experiment was performed in triplicate. Nitrogenase-specific activity was expressed as nmol of C2H2 g−1 h−1 of nodule fresh weight (Vessey, 1994).

Candidate Defense Genes With Enhanced Transcription in Response to Colonization of the Roots by R. etli

To identify genes in common bean that were potentially activated by ISR and that confer resistance to plant pathogens, we carried out searches in studies published on the subject of ISR and defense priming for the genes (according to Mayo et al., 2016). The following P. vulgaris genes were selected (orthologues of Arabidopsis genes): ERF6 (Phvul.002G055800), PR10 (Phvul.002G209500), MYC2 (Phvul.003G285700), NPR1 (Phvul.006G131400), PR1 (Phvul.006G196900), WRKY29 (Phvul.002G293200), WRKY70 (Phvul.009G043100), PAL2 (Phvul.007G150500), and WRKY33 (Phvul.008G251300).

In addition, we analyzed the transcript levels of some of the genes coding for enzymes directly involved in plant hormone synthesis. Specifically, we determined the transcript levels of the gene orthologs to the Arabidopsis AMI1 (Phvul.007G180900) and NIT1 (Phvul.011G096700), both involved in auxin biosynthesis (Barraza et al., 2015b); AAO3 (Phvul.008G210000), an aldehyde oxidase that catalyzes the last step of ABA biosynthesis and a marker for the sites of ABA production (Koiwai et al., 2004) and ABA biosynthesis in leaves (Seo et al., 2004); and BR6OX2.2 (Phvul.004G041700), which catalyzes the last reaction in brassinosteroid (BR) biosynthesis (Kim et al., 2005). The importance of the genes was evaluated by the quantification of their transcripts via qPCR in response to R. etli and pathogen infection.

Quantitative PCR (qPCR) Analysis

qPCR was performed according to Martínez-Aguilar et al. (2016). Data from qRT-PCR experiments were analyzed based on the relative quantification method, or the 2−ΔΔCT method (Livak and Schmittgen, 2001). Fold changes in the target genes were normalized to PvAct11 (Borges et al., 2012) and PvTUB (Livak and Schmittgen, 2001; Barraza et al., 2013, Barraza et al., 2015a), as endogenous controls, and relativized to the expression in control samples (relative gene expression in control plants was defined as 1). All experiments were run in triplicate (technical replicates) from three biological replicates. For a list of all primers used, see Supplementary Table ST1 . Statistical significance was determined as described by Martínez-Aguilar et al. (2016).

Transgenerational Inheritance of Priming

Additional experiments were conducted in the F1 progeny to explore the transgenerational priming effect. First, all common bean plants (F0 generation) from all the different treatments (rhizobacteria only, rhizobacteria plus pathogen, pathogen only, rhizobacteria plus water, and without treatment) were self-pollinated and grown to seed set to generate the F1 progeny. Subsequently, for the transgenerational priming analysis, seeds from the F1 progenies were germinated and exposed to the pathogen only, without rhizobacteria treatment. Plants were inoculated with the pathogen at the age at which the parental lines were infected (17 dag). Samples from inoculated plants were obtained from distal leaves that had not been exposed to the pathogen 24 h before infection, and 24 h and 120 h after infection (or 16, 18, and 22 dag, respectively). All samples were obtained in triplicate and stored at −80°C.

Results

Inoculation With R. etli Protects P. vulgaris Against PspNPS3121

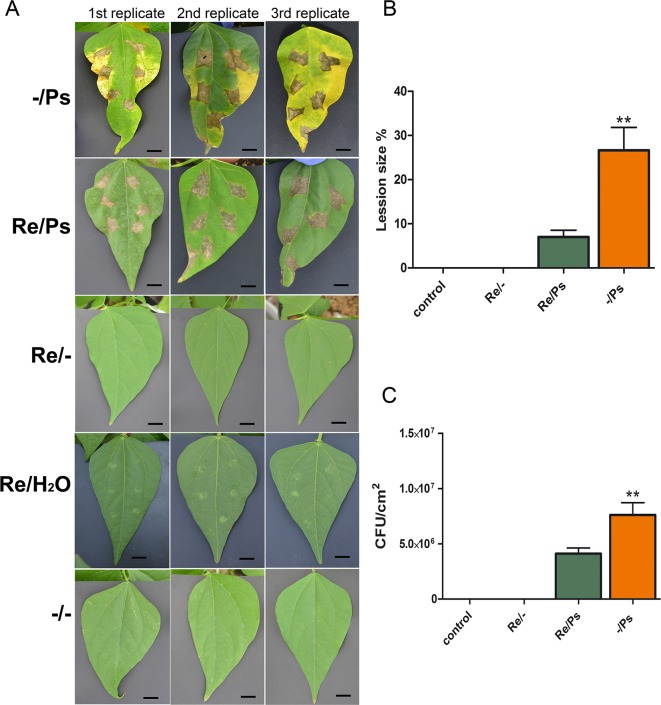

As shown in Figure 1A , inoculation of the symbiont R. etli in cultivar “Rosa de Castilla” before pathogenic bacteria inoculation resulted in a considerable increase in resistance to halo blight disease caused by PspNPS3121. Treatment with R. etli induced a 75% reduction in lesion size (Re/Ps), compared to plants treated with the pathogen only (-/Ps; Figure 1B ). Also, bacterial populations in leaves from plants treated with R. etli and exposed to the pathogen (Re/Ps) were significantly lower, approximately 50% less, than in plants treated with the pathogen only (-/Ps; Figure 1C ). We inferred that common bean plants treated with the R. etli were efficiently protected against PspNPS3121, in contrast to plants that were not primed.

Figure 1.

(A) Leaf damage in common bean plants inoculated with PspNPS3121 (Ps) after treatment with R. etli (Re), or water. Photos were taken 10 days after pathogen inoculation. (B) Lesion size (n = 26) and (C) colony forming units (CFU) of Phaseolus vulgaris plants 10 days after infection with PspNPS3121. Data are mean ± SEM from three independent experiments, and the statistical significance was evaluated using an unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test (** p< 0.05).

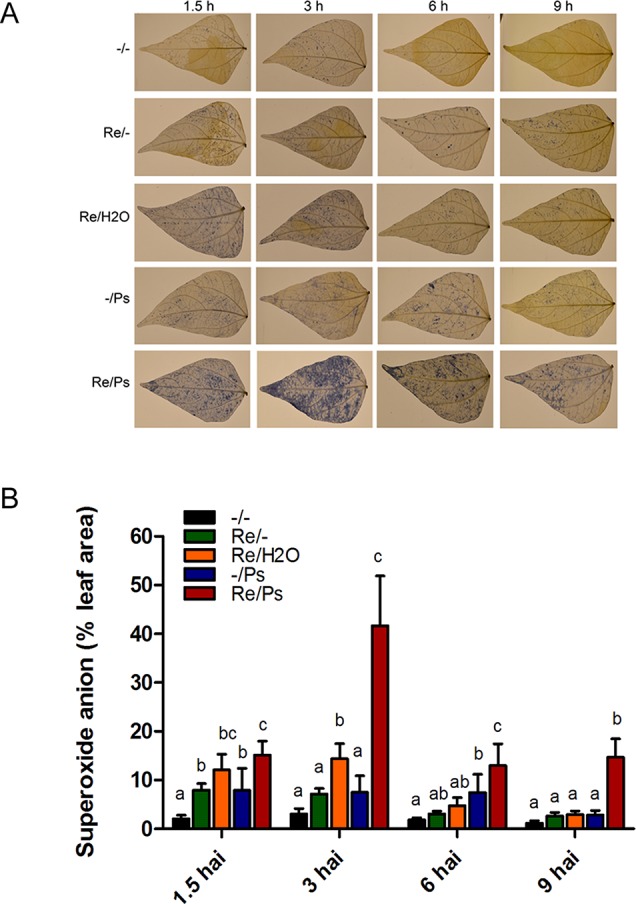

Given that infection development induces oxidative stress, we performed a fast and efficient histochemical assay to examine activation of the induced resistance and to detect accumulation of the reactive oxygen species (ROS) superoxide anion (O2 −) in common bean plants at 1.5, 3, 6, and 9 h after PspNPS3121 infection. Plants inoculated with R. etli and exposed to the pathogen accumulated 3–4 times more O2 − than control plants ( Figure 2 ), and a high accumulation of O2 − was observed 3 h after infection at the whole-leaf level. The above indicates that treatment with R. etli primes common bean plants for improved induction of certain cellular defense responses.

Figure 2.

Histochemical detection of superoxide anion in F0 common bean plants at 1.5, 3, 6, and 9 h after infection (hai). (A) Illustrative photographs from three independent experiments on Phaseolus vulgaris leaves from plants co-cultivated or not with Rhizobium etli, after exposure to PspNPS3121. (B) Quantification of O2 − was performed using the protocol described by Juszczak and Baier, 2014. Images were taken using a digital camera Nikon 5500 (Nikon Corp., Tokyo, Japan). Statistical significance was determined using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s test, p < 0.05. Means with the same letter are not significantly different.

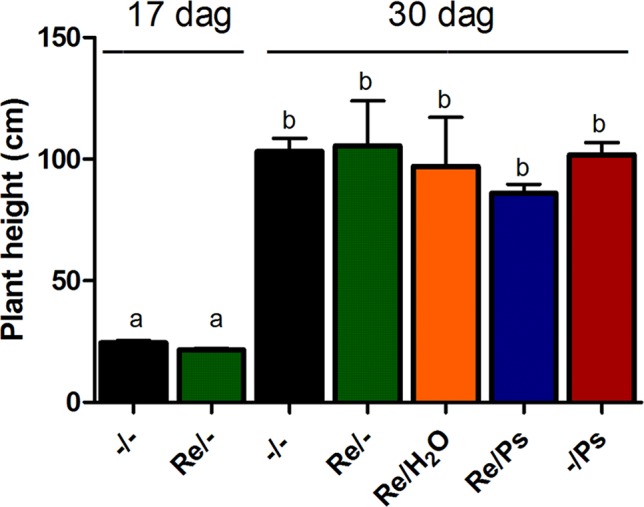

Effect of R. etli Inoculation on Plant Height, Nodule Number and Size, and Acetylene Reduction After Pathogen Infection

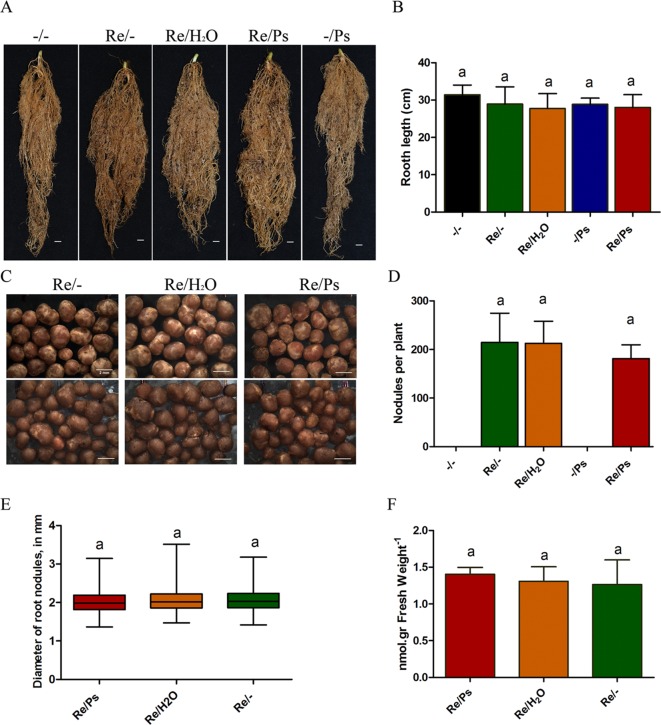

Plant height in all treatments was quantified before pathogen inoculation and 13 days after infection (17 and 30 dag, respectively; Figure 3 ) by measuring the length of the shoot systems from 24 plants per treatment. Plants inoculated with R. etli and exposed to PsNPS3121 were similar in size to plants that were only inoculated with the symbiont, or to the control plants. There were no significant differences in plant height after 13 dpi.

Figure 3.

Plant height before pathogen inoculation and 13 days after infection (17 and 30 dag, respectively). Data are mean ± SEM from 24 independent (n = 24) plants per treatment, from two independent experiments, and were analyzed with one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison tests (P < 0.05). Means with the same letter are not significantly different.

Subsequently, at 13 dpi with PsNPS3121 (or 30 dag), the plants were extracted, the soil removed, and the lengths of the root systems measured. Root system lengths were not influenced by the different treatments ( Figure 4A–B ). In addition, we counted the total number of nodules from six plants from each of the different treatments: (i) R. etli plus PsNPS3121 (Re/Ps), (ii) R. etli plus water (Re/H2O), and (iii) R. etli alone (Re/-). This experiment showed that the numbers of nodules among different treatments are not significantly different ( Figure 4C-D ). We further analyzed the effect of PsNPS3121 on nodule formation by measuring nodule diameter in six plants in each of the different treatments. Nodule diameters from PsNPS3121 infected plants were not significantly different compared to control nodules (Re/H2O and Re/-; Figure 4E ).

Figure 4.

Effects of Rhizobium etli and PsNPS3121 on roots and nodules of Phaseolus vulgaris. (A, B) Lengths of the root systems. Data are mean ± SD from 12 independent plants (n = 12). (C, D) Total number of nodules from each of the different treatments: plants inoculated with R. etli alone or R. etli plus PsNPS3121. Data are mean ± SD from nine independent plants (n = 9). (E) Diameters of nodules in mm. Data are mean ± SD from 50 nodules in nine independent plants (n = 450). Results are expressed as means and quartiles (box plots). (F) Acetylene reduction assay. Data are mean ± SD from six independent plants (n = 6). Statistical significance was determined using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s test, p < 0.05. Means with the same letter are not significantly different.

Subsequently, we evaluated nitrogen fixing activity in nodules. By measuring nitrogen fixation (nitrogenase activity), via an acetylene reduction assay, we observed that all plants from the Re/Ps treatment had capacity for nitrogen fixation similar to the control nodulated roots ( Figure 4F ).

R. etli Prime Plants for Enhanced Expression of Defense Related Genes

Next, we performed a methodical analysis to select illustrative common bean genes, based on their involvement in plant defense and priming, for their expression analysis by qPCR (according to Mayo et al., 2016). After conducting an exhaustive literature review, we selected and identified the corresponding genes at the NCBI and Phytozome databases. Based on transcriptomic data available at the Phytozome, several genes were selected according to their expression patterns (genes with low or no expression in leaves were eliminated). After we confirmed their expression in common bean leaves, three types of genes were selected: (a) genes highly expressed in leaves, (b) genes exhibiting medium expression levels in leaves, and (c) genes exhibiting low expression levels in leaves ( Table 2 ).

Table 2.

Genes selected for defense response and priming, and their experimental expression during ISR in Phaseolus vulgaris leaves.

| Gene | Reference | Accession Number NCBI | Phytozome Id | Functional annotation at Phytozome | Expression level in common bean leaves |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ERF6 | Huang et al., 2016; Sewelam et al., 2013 | XP_007157260.1 | Phvul.002G055800 | EREBP-like factor (EREBP) | Low |

| PR10 | Gao et al., 2012 | XP_007159109.1 | Phvul.002G209500 | Pathogenesis-related protein Bet v I family (Bet_v_1) | Low |

| MYC2 | Pozo et al., 2008; Kazan and Manners, 2013 | XP_007156435.1 | Phvul.003G285700 | Transcription factor MYC2 | Medium |

| PR1 | Zimmerli et al., 2000; Martinez-Aguilar et al., 2016; Slaughter et al., 2012; Luna et al., 2014 | XP_007148301.1 | Phvul.006G196900 | Pathogenesis-related protein 1 (PR1) | Medium |

| WRKY29 | Martínez-Aguilar et al., 2016; Singh et al., 2014 | XP_007160109.1 | Phvul.002G293200 | WRKY DNA-binding domain (WRKY) | Medium |

| WRKY70 | Alvarez-Venegas et al., 2007; Luna et al., 2014 | XP_007136415.1 | Phvul.009G043100 | WRKY DNA-binding domain (WRKY) | Medium |

| PAL2 | Kohler et al., 2002 | XP_007144370.1 | Phvul.007G150500 | Phenylalanine ammonia lyase | High |

| WRKY33 | Zheng et al., 2006; Birkenbihl et al., 2012 | XP_007142085.1 | Phvul.008G251300 | WRKY transcription factor 33 (WRKY33) | High |

| NPR1 | Kohler et al., 2002; Van der Ent et al., 2009a; Van der Ent et al., 2009b; Luna et al., 2012 | XP_007147518.1 | Phvul.006G131400 | Regulatory protein NPR3related | High |

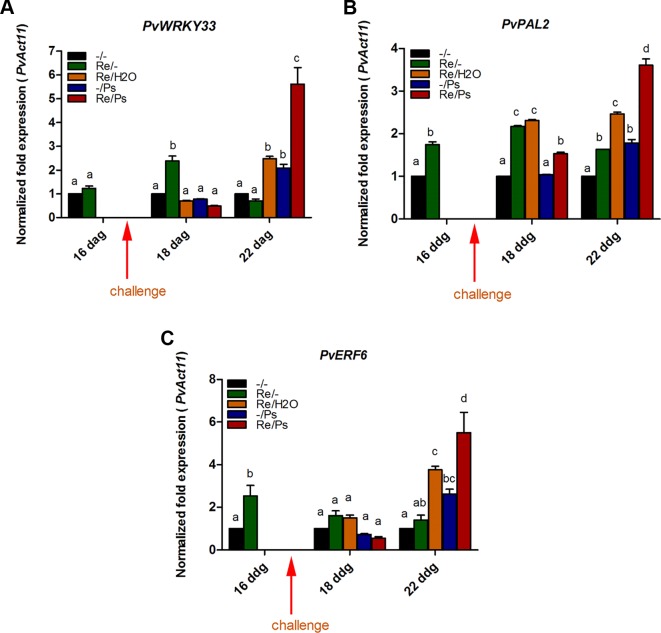

Accordingly, we examined the effect of R. etli inoculation (priming) on the transcription levels of nine genes related to ISR and defense and potentially involved in priming. Samples were obtained from plants treated with R. etli (Re/-) only, with the pathogen (Ps/-) only, or during the interaction with R. etli and exposed to the pathogen (Re/Ps). After qPCR analysis, the transcript levels of only three genes from plants that had been primed with R. etli and inoculated with PspNPS3121 showed a transcriptional pattern characteristic of the priming response (e.g., biphasic curve). In systemically resistant leaves of R. etli–treated plants, priming alone did not enhance transcription of PvWRKY33, PvERF6, and PvPAL2. However, 120 h after pathogen inoculation, there was high accumulation of transcripts, compared to the control plants ( Figure 5 and Supplementary Figure SF1 ). WRKY33 is a transcription factor (TF) involved in the activation of the salicylic acid (SA)–related host response (Birkenbihl et al., 2012); ERF6 is a TF that activates expression of PR genes (Huang et al., 2016), whereas PAL2 functions in plant secondary metabolites synthesis and callose deposition (Kohler et al., 2002). Consequently, R. etli primed P. vulgaris plants for potentiated gene activation, which was subsequently induced by PspNPS3121 infiltration.

Figure 5.

Transcript levels of genes involved in plant defense. (A) PvWRKY33; (B) PvPAL2; (C) PvERF6. Plants were primed with R. etli, followed by inoculation with PspNPS3121 (Re/Ps), inoculated only with the symbiont (Re/- ; and water, Re/H2O), infected only (-/Ps), or neither primed nor inoculated (control, -/-). Data were normalized to the Actin11 (PvActin11) and Tubulin (PvTUB, see Supplementary Figure SF1 ) reference genes. Data represent mean ± SD from three independent experiments (n = 3). Statistical significance was determined using two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test, p < 0.05. Dag: days after germination. Means with the same letter are not significantly different.

On the contrary, there was enhanced transcription of PvPR1 in the late stages of priming (120 h after bacterial inoculation; Supplementary Figure SF2 ). Such a transcriptional pattern, however, was also induced by the pathogen alone. Therefore, the rest of the genes could not be considered as having been primed, under the present experimental conditions.

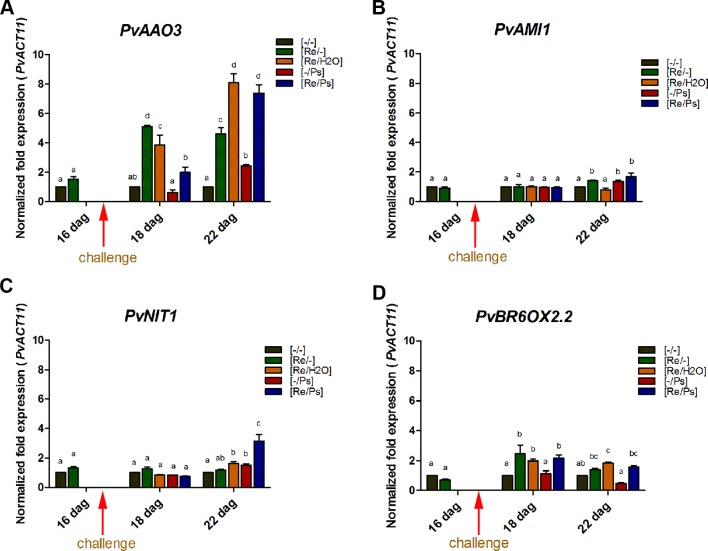

R. Etli Activates the Expression of Genes Involved Plant Hormone Biosynthesis

Plant hormones regulate numerous developmental processes and signaling networks involved in plant responses to different types of biotic and abiotic stresses (Bari and Jones, 2009). Furthermore, the study of key genes and enzymes involved in plant hormone biosynthesis provides important information concerning the regulation of plant hormones pathways and can offer new information regarding the function of plant hormones during plant-microbe interactions (Seo et al., 2004). Thus, we determined the transcript levels of some key genes involved in the synthesis of auxins (IAA; involved in the modulation of defense and development responses; Bari and Jones, 2009), ABA (involved in biotic stress; Ton and Mauch-Mani, 2004; Ton et al., 2009), and BR (implicated in induced systemic tolerance to biotic stress and in the modulation of plant defense responses; Bari and Jones, 2009; Li et al., 2013) ( Figure 6 and Supplementary Table ST1 ). Specifically, we determined the transcript levels of the AMI1 (INDOLE-3-ACETAMIDE HYDROLASE 1), NIT1 (NITRILASE 1), AAO3 (ABSCISIC ALDEHYDE OXIDASE 3), and BR6OX2.2 (BRASSINOSTEROID-6-OXIDASE 2 ISOFORM 2). Compared to control plants ( Figure 6 and Supplementary Figure SF3 ), the transcripts of PvAAO3 (which codes for an enzyme that catalyzes the last step in the ABA biosynthesis pathway, from abscisic aldehyde to ABA; Koiwai et al., 2004; Seo et al., 2004) and PvBR6OX2.2 (enzyme that catalyzes the last step in the production of brassinolide; Kim et al., 2005) increased in all treatments where the plants were inoculated with R. etli. As shown in Figure 6 , there was an induction in PvAAO3 and PvBR6OX2.2 transcripts in all three samples that were inoculated with R. etli (Re/-, Re/H2O, Re/Ps). In control plants (-/-) or in plants treated with the pathogen only (-/Ps), however, the transcript levels of PvAAO3 and PvBR6OX2.2 remained very low. Intriguingly, infiltration with water (Re/H2O), after R. etli inoculation, resulted in similar PvAAO3 and PvBR6OX2.2 transcript levels to the Re/Ps treatment (at 24 h and 120 h after PspNPS3121 infection, respectively), indicating that their induction was potentiated by treatment with water. This result suggests that R. etli inoculation enhances transcription of PvAAO3 and PvBR6OX2.2, which in turn could increase ABA and brassinolide synthesis, independently of PspNPS3121 infection. The rest of the genes analyzed (PvNIT1, PvAMI1), involved in auxin biosynthesis, did not show significant changes in their transcripts as a result of the different treatments.

Figure 6.

Transcript levels of genes involved in plant hormone biosynthesis. (A) PvAAO3; (B) PvAMI1; (C) PvNIT1; (D) PvBROX2.2. Plants were primed with R. etli, followed by inoculation with PspNPS3121 (Re/Ps), inoculated only with the symbiont (Re/- ; and water, Re/H2O), infected only (-/Ps), or neither primed nor inoculated (control, -/-). Data were normalized to the Actin11 (PvActin11) and Tubulin (PvTUB, see Supplementary Figure SF3 ) reference genes. Data represent mean ± SD from three independent experiments (n = 3). Statistical significance was determined using two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test, p < 0.05. Dag: days after germination. Means with the same letter are not significantly different.

R. etli–Induced Callose Deposition in P. vulgaris

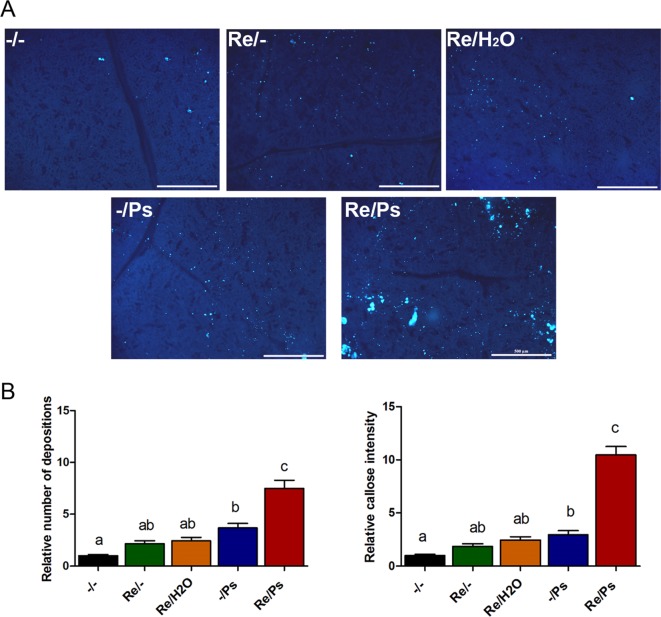

To quantify activity of plant defense response, we determined callose deposition (a quick cellular defense outcome; Kohler et al., 2002), in response to R. etli inoculation and to PspNPS3121 infection. After bacterial treatment, common bean leaves were stained with aniline blue analyzed by epifluorescence microscopy, and callose was quantified and documented as the “relative number of callose-corresponding pixels (callose intensity) or the relative number of callose depositions” (Luna et al., 2011). As shown in Figure 7 , plants primed with R. etli and inoculated with PspNPS3121 (Re/Ps) showed an increase in the number of callose depositions and callose intensity compared to the rest of the different treatments (Re/H2O; -/Ps; Re/-), depicting the primed callose response. Furthermore, the size of the individual callose depositions was larger in Re/Ps treated plants, indicating that R. etli enhanced the production of callose and generated greater amounts of callose per deposition, which was induced by PspNPS3121 infection.

Figure 7.

Phenotype of R. etli-induced callose in F0 generation. (A) Morphological differences of callose depositions in 17 days-old P.vulgaris plants (co-cultivated with the symbiont), after PspNPS3121 infection. Representative photographs of aniline blue-stained leaves under UV epifluorescence illustrate differences in callose deposition between treatments. (B) Relative quantification of callose (number of individual depositions per unit of leaf surface) and callose intensity (number of fluorescent callose-corresponding pixels relative to the total number of pixels) were determined by using the Fiji software (according to Jin and Mackey, 2017). Values represent means (±SEM, n=24). Statistical significance was determined using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test, p < 0.05). Scale bar = 500 µm. Means with the same letter are not significantly different.

The number of depositions and callose intensity between control plants (-/-) and plants inoculated only with the symbiont (Re/-; Re/H2O) did not differ statistically. Whereas the relative number of depositions and intensity did not differ statistically between plants inoculated only with the symbiont (Re/-; Re/H2O) and plants infected only with the pathogen (-/Ps).

Transgenerational Inheritance of Priming in the Common Bean

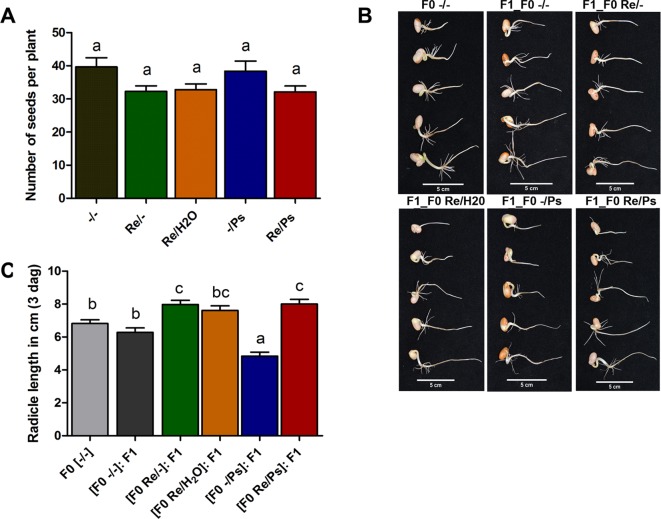

To evaluate if R. etli–primed plants had the potential to generate an transgenerational memory and produce offspring that are more resistant to the halo blight disease than progeny of unprimed parents, all plants (F0 generation), from all the different treatments (-/-, Re/-, Re/H2O, -/Ps, and Re/Ps), were self-pollinated and grown to seed set to generate the F1 progeny.

As shown in Figure 8A , there was no significant difference in the number of seeds produced by plants treated with R. etli (Re/-, Re/H2O, Re/Ps) and the number of seeds produced by control plants (-/-) or plants treated with the pathogen only (-/Ps). However, there was a marginal difference between plants that were nitrogen-supplemented (-/- and -/Ps) and plants that were fertilized with a nitrogen-free solution (Re/-, Re/H2O, Re/Ps). The results suggest that R. etli directly or indirectly protected its hosts against pathogen attack, and its presence facilitates the maintenance of proper crop yield.

Figure 8.

(A) Number of seeds produced in plants from the different treatments (Re/Ps, Re/H2O, Re/-; -/Ps, and -/-). Data are mean ± SD from six independent plants (n = 6) per experiment, from three independent experiments. (B-C) Radicle length of F1 seedlings three days after germination. Scale = 5 cm. Data are mean ± SD from 75 independent seeds (n = 75), from three independent experiments. Statistical significance was determined using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test, p < 0.05. Means with the same letter are not significantly different.

Next, we germinated F1 seeds from all the different F0 treatments (-/-, Re/-, Re/H2O, -/Ps, and Re/Ps) in germination trays under sterile conditions, and the lengths of the radicles were measured 3 dag, before transferring the seedlings to pots. There were significant differences in radicle length in F1 seedlings when compared with F0 control seedlings ( Figure 8B, C ). Particularly, seedlings from plants that were treated with the pathogen only in the F0 generation were 29% shorter than the untreated control plants. Notably, seedlings from plants that were treated with the symbiont in the F0 [(F0 Re/Ps): F1; (F0 Re/-): F1; Figure 8C ] had radicles that were 17% longer than the radicles in the control plants (F0 -/-).

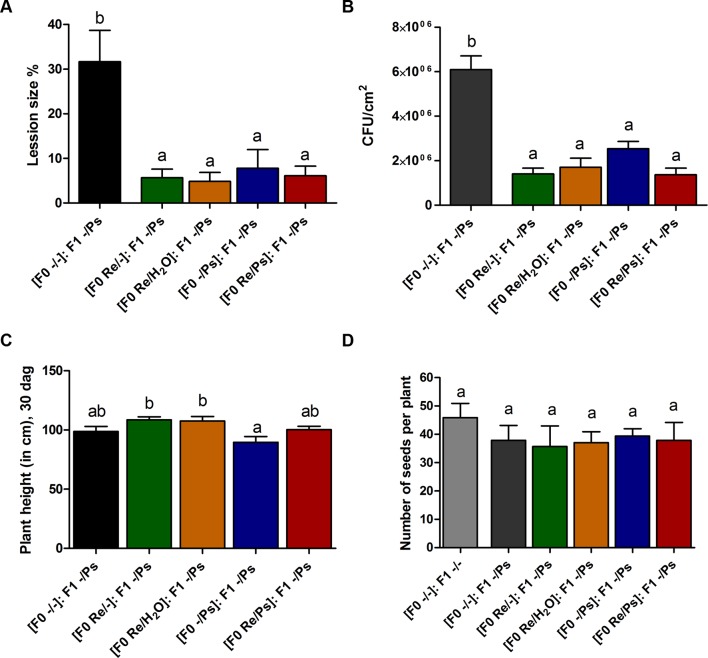

At 17 dag, two trifoliate leaves from all F1 plants were exposed to PspNPS3121 [(F0 Re/Ps): F1 -/Ps; (F0 Re/H2O): F1 -/Ps; (F0 Re/-): F1 -/Ps; (F0 -/Ps): F1 -/Ps]. Treatment with the pathogen resulted in a 5–8% lesion size (of total leaf area), among all plants—that is, an 85% reduction in lesion size when compared to the control plants [(F0 -/-): F1 -/Ps] ( Figure 9A ). In addition, PspNPS3121 bacterial populations (CFU) in leaves from plants treated with R. etli in the F0 generation and exposed to the pathogen in the F1 generation [(F0 Re/Ps): F1 -/Ps; (F0 Re/H2O): F1 -/Ps; (F0 Re/-): F1 -/Ps] were significantly lower than in the control plants treated with the pathogen only ([F0 -/-]: F1 -/Ps) ( Figure 9B ). Therefore, common bean plants treated with R. etli in the F0 generation were effectively protected in the F1 generation against PspNPS3121, in contrast to plants that were not primed [(F0 -/-): F1 -/Ps]. Moreover, F0 plants that were treated with the pathogen only (“sensitized”; Conrath, 2009) and exposed to the pathogen in the F1 generation [(F0 -/Ps): F1 -/Ps] also have shown lower CFUs compared to the control plants ( Figure 9B ). We inferred that infection with PspNPS3121, in the F0 generation, induced enhanced pathogen defense (priming effect) in the F1 generation against the halo blight bacterial disease. However, continuous exposure to the pathogen [(F0 -/Ps): F1 -/Ps] influenced plant height when compared to plants that were primed with R. etli in the F0 generation ( Figure 9C ). That is, plants exposed only to the pathogen in F0 and F1 [(F0 -/Ps); (F0 -/Ps): F1 -/Ps; Figure 9C ] were 17% shorter 30 dag than plants inoculated with the symbiont [(F0 Re/H2O): F1 -/Ps; (F0 Re/-): F1 -/Ps; Figure 9C ]. However, there was no significant difference in the number of seeds produced between F1 plants treated PspNPS3121 and the control plants (-/-) ( Figure 9D ).

Figure 9.

Transgenerational priming effect. (A) Lesion size and (B) colony forming units (CFU) in F1 common bean plants 10 days after infection with PspNPS3121. Data are mean ± SEM from three independent experiments. (C) Plant height 13 days after infection (30 dag). Data are mean ± SEM from 24 independent (n = 24) plants per treatment, from two independent experiments. (D) Number of seeds produced in F1 plants from the different treatments (Re/Ps, Re/H2O, Re/-; -/Ps, and -/-). Data are mean ± SD from six independent plants (n = 6) per experiment, from three independent experiments. Statistical significance was determined using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test, p < 0.05. Means with the same letter are not significantly different.

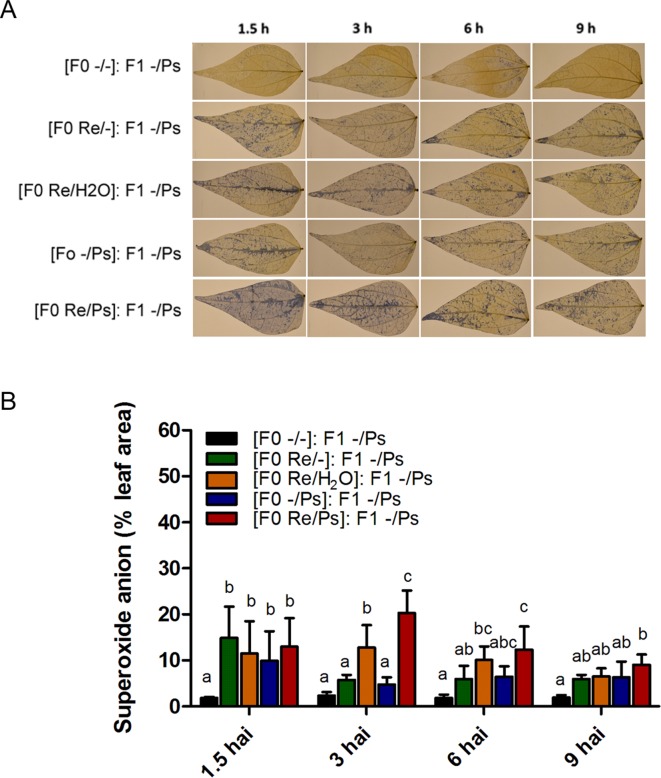

We next wished to examine the activation of the induced resistance in F1 plants by detecting accumulation of the O2 − at 1.5, 3, 6, and 9 h after PspNPS3121 infection ( Figure 10 ). All plants from the F0 generation, when exposed to the pathogen in the F1 generation, accumulated more O2 − than control plants [(F0 -/-): F1 -/Ps], at 1.5 h after infection. However, higher accumulation of O2 − was observed 3 h after infection at the whole-leaf level, in leaves from plants treated with R. etli and PspNPS3121 in the F0 generation and exposed to the pathogen in the F1 generation [(F0 Re/Ps): F1 -/Ps], as well as in plants treated with R. etli and water [(F0 Re/H2O): F1 -/Ps], when compared to control plants ( Figures 7A, B ). Such O2 − accumulation pattern suggests a transgenerational effect in plants primed in the F0 generation with R. etli (“bacterizing the roots,” or root colonized by bacteria; Van Peer et al., 1991) and induced in the F1 by PspNPS3121 on cellular defense responses.

Figure 10.

Histochemical detection of superoxide anion in F1 common bean plants at 1.5, 3, 6, and 9 h after infection. Seeds from all F0 plants (-/-, Re/-, Re/H2O, -/Ps, and Re/Ps) were germinated and F1 progeny plants were challenged with the pathogen. (A) Illustrative photographs from three independent experiments on Phaseolus vulgaris leaves from F1 plants after exposure to PspNPS3121. (B) Quantification of O2 − was performed using the protocol described by Juszczak and Baier, 2014. Images were taken using a digital camera Nikon 5500 (Nikon Corp., Tokyo, Japan). Statistical significance was determined using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s test, p < 0.05. Means with the same letter are not significantly different.

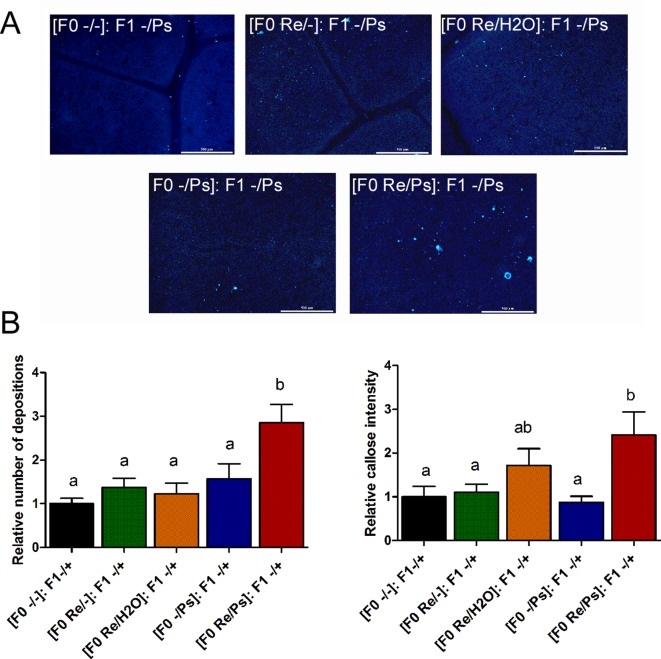

In addition, to determine whether the primed callose response has a transgenerational effect against PspNPS3121, we analyzed callose depositions in the F1 generation of all the different treatments, after exposure to the pathogen [(F0 -/-): F1 -/Ps; (F0 -/Ps): F1 -/Ps; (F0 Re/H2O): F1 -/Ps; (F0 Re/-): F1 -/Ps; (F0 Re/Ps): F1 -/Ps]. As shown in Figure 11 , plants treated with R. etli and PspNPS3121 in the F0 generation and exposed to the pathogen in the F1 generation [(F0 Re/Ps): F1 -/Ps] showed a faster and stronger accumulation of callose depositions after pathogen infection, even though the relative number of depositions was 2.6 times lower than in the F0 generation. This suggests that the ability to produce callose in F1 is caused by the priming effect in the F0. Plants from the rest of the treatments, however, failed to accumulate enhanced levels of callose after pathogen treatment.

Figure 11.

Phenotype of R. etli-induced callose in F1 generation. (A) Morphological differences of callose depositions in 17 days-old P.vulgaris F1 plants. Seeds from the F1 progenies were germinated and exposed to the pathogen only, without rhizobacteria treatment. Representative photographs of aniline blue-stained leaves under UV epifluorescence illustrate differences in callose deposition between treatments. (B) Relative quantification of callose (number of individual depositions per unit of leaf surface) and callose intensity (number of fluorescent callose-corresponding pixels relative to the total number of pixels) were determined by using the Fiji software (according to Jin and Mackey, 2017). Values represent means (±SEM, n=24). Statistical significance was determined using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test, p < 0.05). Scale bar = 500 µm. Means with the same letter are not significantly different.

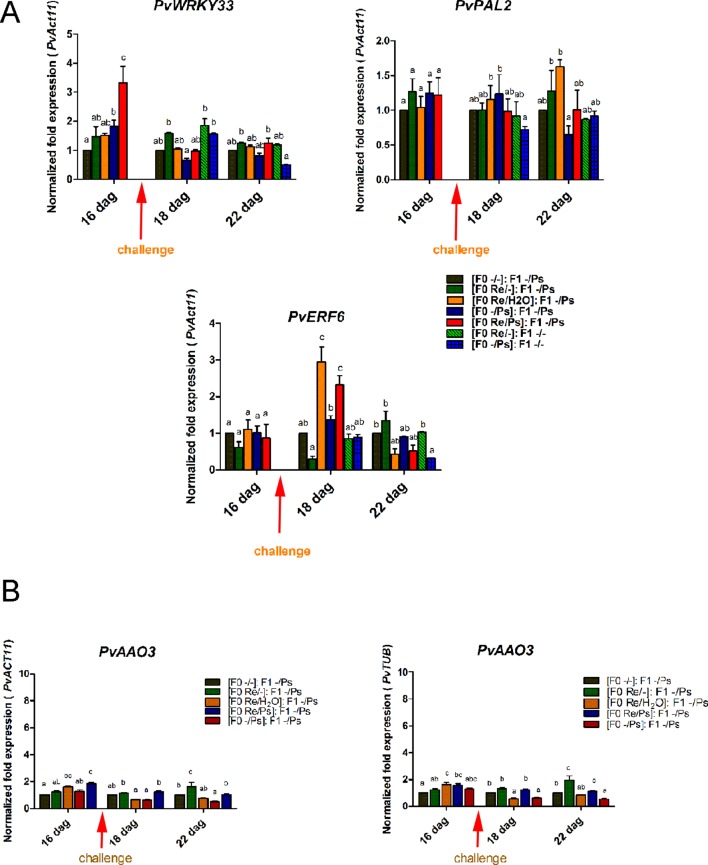

We then selected the primed-responsive genes (PvWRKY33, PvPAL2, and PvERF6) highly induced against PspNPS3121 in the parental generation (F0) and analyzed their expression patterns in the F1 generation before and after pathogen attacks ( Figure 12 and Supplementary Figure SF4 ). As shown in Figure 12A , the genes that exhibited an enhanced transcription pattern following pathogen attack were PvERF6 (2.5 to three-fold induction, 24 h after infection) and PvPAL2 (0.5-fold induction, 24 h after infection) when compared to control plants. Consistent with previous results, the finding suggests a transgenerational effect in common bean plants that were primed in the F0 generation with R. etli and induced by PspNPS3121 infiltration. In addition, F0 plants treated with R. etli were sensitized and displayed enhanced PvPAL2 and PvERF6 transcript levels in the F1 generation. However, expression levels of the ABA-synthesis-related gene PvAAO3, in the F1 generation (without R. etli inoculation), were not significantly different before and after PspNPS3121 infiltrations and also with respect to the control {[(F0 -/-): F1 -/-]; Figure 12B }. This suggests that inoculation with R. etli is required for PvAAO3 expression and ABA synthesis and that PvAAO3 expression is not directly related to the transgenerational induced resistance, under the present experimental conditions.

Figure 12.

Transgenerational transcript levels of common bean genes. (A) Transcript levels of genes involved in plant defense. (A) PvWRKY33; (B) PvPAL2; (C) PvERF6. F0 plants were self-pollinated and grown to seed set to generate the F1 progeny. Seeds from the F1 progenies were germinated and exposed to the pathogen only, without rhizobacteria treatment. Samples were obtained at 16, 18, and 22 dag. Data were normalized to the actin11 (PvActin11) and tubulin (PvTUB, see Figure SF4 ) reference genes. (B) Transcript levels of the PvAAO3 gene involved in ABA synthesis. Data were normalized to the actin11 (PvActin11) and tubulin (PvTUB) reference genes. Data are mean ± SD from three independent experiments (n = 3). Statistical significance was determined using two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test, p < 0.05. Dag, days after germination.

Discussion

Common bean is a valuable crop worldwide and an important grain legume in the human diet. Common bean production, however, is affected by numerous pathogens. Some of the major approaches for controlling common bean infectious diseases include crop rotation, sanitation, using certified seeds, growing resistant cultivars, stress and wound avoidance, chemical control or application of pesticides, and to a lesser extent, the use of bacterial biocontrol agents and PGPR. In legumes, the use of PGPR has been mostly limited to rhizobia manipulation in studies aimed at improving legume growth and development, particularly via nodulation and nitrogen fixation (Pérez-Montaño et al., 2014). In addition, several studies have examined the hypothesis that PGPR might enable plants to maintain their yield with reduced fertilizer application rates (Yang et al., 2009).

PGPR also suppress disease-causing microbes by activating the ISR plant defense system. In addition, legume-Rhizobium interactions induce PGPR “like-responses,” improving tolerance/resistance to different types of stress (Fernandez-Göbel et al., 2019). However, few reports have been published on Rhizobium as elicitors of resistance to bacterial diseases (Osdaghi et al., 2011). Therefore, the goals of the present study were, first, to determine whether the symbiont R. etli elicits the ISR in P. vulgaris against PspNPS3121. Second is to determine if R. etli has a role in decreasing or inhibiting the harmful effects of PspNPS3121 on plant growth, development, and nitrogen fixation in R. etli treated bean plants. Achievement of the above goals could facilitate the use R. etli (and rhizobacteria in general) as a defense-priming agent to induce ISR in P. vulgaris to minimize susceptibility to pathogens and enhance plant breeding activities and overall crop productivity. Therefore, we studied the effect of priming on gene activation and the generational effect of the primed state using R. etli as an elicitor.

Inoculation of common bean with R. etli reduced halo blight severity when compared to plants not treated with the symbiont. For example, foliar pathogen lesion size was 75% lower in the R. etli inoculated plants, than in the non-inoculated plants, while PspNPS3121 CFU was 50% lower in R. etli inoculated plants. Therefore, the symbiotic relationship between R. etli and common bean reduced disease incidence. The finding is notable since any method that can reduce the foliar symptoms of halo blight disease at low costs and in an environmentally safe manner (e.g., without the application of commercial pesticides) is of considerable importance in agriculture.

In our experiments, there were no significant changes in root length, diameter and number of nodules, and nitrogen fixation (nitrogenase activity) among the different treatments. The finding is also critical, since the effects of co-inoculation of R. etli and PspNPS3121 on common bean suggest that R. etli improves tolerance against halo blight disease without affecting crop productivity. Although further studies are required to corroborate the effectiveness of distinct strains of Rhizobium spp. in reducing the incidence of halo blight disease, the utilization of R. etli in common bean planting areas is recommended and could be an alternative to the application of synthetic pesticides and fertilizers.

Accordingly, inoculation with R. etli elicited ISR and primed the whole plant for enhanced defense against PspNPS3121. Aboveground parts of the plant (foliar tissue) acquired an enhanced level of resistance against infection by the PspNPS3121 pathogen following inoculation with R. etli. In addition, R. etli–treated plants exhibited considerably higher ROS superoxide anion accumulation at non-toxic levels at the site infected by the pathogen. Moreover, during the different stages of the symbiotic interaction, ROS can be translocated extensively. Therefore, the systemic redox signaling plays an important role in the regulation of systemic acclimatory mechanisms under stress conditions (Fernandez-Göbel et al., 2019). Consequently, ROS signaling networks control a wide range of biological processes, including responses to biotic stimuli, and functions as a general priming signal in plants (Baxter et al., 2014). Moreover, plant defense hormones modulate plants’ ROS status (Sewelam et al., 2013), which suggests that inoculation of R. etli to the root system sensitized distal plant parts for enhanced pathogen defense (priming effect). Therefore, long-term responses (Mittler et al., 2011) enhanced the oxidative stress defense capacity in common bean leaves when exposed to the PspNPS3121 pathogen.

Interestingly, our study demonstrates that plants treated with R. etli responded more efficiently to pathogen attack via an augmented deposition of callose. Thus, R. etli sensitizes or primes P. vulgaris plants for stronger accumulation of callose biosynthesis at the site of infection, under the present experimental conditions. Hence, we propose that R. etli–induced superoxide anion accumulation promotes callose deposition.

R. etli–treated plants exhibited a potentiated defense-related gene expression. The transcript levels of PvWRKY33, PvERF6, and PvPAL2 exhibited a typical priming response. Although R. etli did not trigger their expression, after PspNPS3121 inoculation, transcripts accumulated at levels higher than in the unprimed, inoculated controls. In plants, a large number of WRKY genes code for TF induced by pathogen infection are involved in plant defense responses and regulate cross-talk between JA- and SA-regulated disease response pathways (Zheng et al., 2006). In Arabidopsis—for example, WRKY33 TF interacts with MAP kinase 4 (MPK4) and MKS1 within the nucleus and upon exposure to PsDC3000 or following elicitation with flg22 (a 22-amino acid sequence of flagellin), WRKY33 is released from the trimeric complex and targets the promoter of PHYTOALEXIN DEFICIENT3 (PAD3), encoding an enzyme necessary for the synthesis of antimicrobial camalexin, a phytoalexin with antimicrobial and antioxidative properties (Qiu et al., 2008). In addition, inoculation with R. etli greatly enhanced Phenylalanine AMMONIA-LYASE2 (PAL2) expression induced by PspNPS3121 infection. PAL genes catalyze the first step in the phenylpropanoid pathway, where L-phenylalanine undergoes deamination to produce trans-cinnamate and ammonia. PAL is also involved in cellular defense responses and the formation of lignin, phytoalexins, coumarins, and other flavonoids (Zhang et al., 2017). Furthermore, it has been shown that PAL2 functions in callose deposition (Kohler et al., 2002). ETHYLENE RESPONSE FACTOR 6 (ERF6), a defense activator involved in Arabidopsis immunity, is also induced upon pathogen attack via the activation of mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs/MPKs) (Huang et al., 2016). ERF6 also plays a key role in oxidative stress signaling and is necessary for the expression of antioxidant genes in response to biotic and abiotic stresses (Sewelam et al., 2013).

Primed plants responded more efficiently to PspNPS3121 attack by a higher level of superoxide anion production, a faster and stronger accumulation of callose, and a faster activation of plant defense gene expression. In addition, treatment with R. etli increased the transcript levels of the ABA-synthesis-related gene PvAAO3, after pathogen attack. Suggesting the activation of an ABA-dependent defense mechanism in primed plants (Ton and Mauch-Mani, 2004). Actually, it has been shown that ABA functions as a positive regulator of disease resistance through—for example, potentiation of callose deposition (Ton and Mauch-Mani, 2004; Ton et al., 2005; Flors et al., 2008). Furthermore, environmental conditions such as light, drought, and salt stress have been suggested to regulate ABA biosynthesis (Xiong and Zhu, 2003). This could explain the higher expression levels of the PvAAO3 gene in R. etli–treated plants that were inoculated with water. Thus, ABA displays an important function in plant defense and its task depends on distinctive plant-microorganism interactions (Bari and Jones, 2009).

Therefore, R. etli facilitated greater and more rapid activation of defense-related genes following infection with the pathogen, which suggests that priming is an important cellular mechanism in ISR in common bean plants. In addition to the critical role of rhizobacteria in plant growth and development, and in maintaining soil fertility, the indirect biotic stress tolerance effect induced by R. etli inoculation should be considered as a major factor influencing the activities of phytopathogenic microorganisms.

Plants exposed to the pathogen in the F1 generation exhibited reduced lesion sizes, low numbers of pathogenic bacterial populations (CFU), and higher transcript levels of PvERF6 and PvPAL2, when compared with the control plants. The results indicate that R. etli–primed plants could develop a transgenerational defense memory and could produce offspring that are more resistant to the halo blight disease. However, the accumulations of superoxide anion and callose deposition, in the F1 generation, were much lower than those detected in the F0, and the expression of the PvAAO3 gene remained without change, after pathogen attack. Notably, up-regulation of PvERF6 (an ET-independent TF that activates expression of PR genes; Huang et al., 2016) suggests that the transgenerational defense mechanisms implicated in common bean protection mediated by R. etli could encompass ET-independent signaling pathway.

Conclusions

The use of rhizobacteria can stimulate ISR in plants, with the potential to transform modern agriculture; however, research on the exploitation of PGPR remains limited. Considering the positive effects of R. etli on crop productivity in the form of biotic stress tolerance and generational and transgenerational inheritances of priming effects, in addition to N-fixation and reduced pesticide application rates, adoption of ISR and PGPR in agriculture should be encouraged as a tool for managing plant stress. Nevertheless, more studies are required to explore the role of root nodule symbiosis and plant innate immunity under stressful conditions such as disease infestation.

Data Availability Statement

All datasets for this study are included in the manuscript/ Supplementary Files .

Author Contributions

RA-V provided the idea of the work. RA-V and AD-V designed the experiments. AD-V and AL-C conducted the experiments and performed the statistical analysis. RA and AD-V participated in the interpretation of results and critically reviewed the manuscript. RA-V wrote the paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by Consejo Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnología, grant CB-2015/257129 to RA-V.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank José Antonio Vera-Núñez for assistance with the acetylene reduction analysis.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpls.2019.01317/full#supplementary-material

Transcript levels of genes involved in plant defense as determined by q-PCR at various days after germination (dag). (A) PvWRKY33; (B) PvPAL2; (C) PvERF6. Plants were primed with R. etli, followed by inoculation with P. syringae pv. phaseolicola (Re/Ps), inoculated with the symbiont only (Re/- ; and water, Re/H2O), infected only (-/Ps), or neither primed nor inoculated (control, -/-). Data were normalized to the Tubulin (PvTUB) reference gene. Data are mean ± SD from three independent experiments (n = 3). Statistical significance was determined using two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test, p<0.05. Dag: days after germination. Means with the same letter are not significantly different.

Transcript levels of genes involved in plant defense. q-PCR analysis was performed at 16, 18, and 22 days after germination (dag). (A) PvPR1; (B) PvPR10; (C) PvWRKY29, (D) PvWRKY70; (E) PvNPR1; (F) PvMYC2. Plants were primed with R. etli, followed by inoculation with PsNPS3121 (Re/Ps), inoculated only with the symbiont (Re/- ; and water, Re/ H2O), infected only (-/Ps), or neither primed nor inoculated (control, -/-). Data were normalized to the PvActin11 reference gene. Data are mean ± SD from three independent experiments (n = 3). Statistical significance was determined using two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test, p<0.05. Dag: days after germination. Means with the same letter are not significantly different.

Transcript levels of genes involved in plant defense. q-PCR analysis was performed at 16, 18, and 22 days after germination (dag). (A) PvAAO3; (B) PvAMI1; (C) PvNIT1; (D) PvBROX2.2. F0 plants were self-pollinated and grown to seed set to generate the F1 progeny. Seeds from the F1 progeny were germinated and exposed to the pathogen only, without rhizobacteria treatment. Samples were obtained at 16, 18, and 22 dag. Data were normalized to the Tubulin (PvTUB) reference gene. Data are mean ± SD from three independent experiments (n = 3). Statistical significance was determined using two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test, p<0.05. Dag: days after germination. Means with the same letter are not significantly different.

Transgenerational transcript levels of genes involved in plant defense. (A) PvWRKY33; (B) PvPAL2; (C) PvERF6. F0 plants were self-pollinated and grown to seed set to generate the F1 progeny. Seeds from the F1 progeny were germinated and exposed to the pathogen only, without rhizobacteria treatment. Samples were obtained at 16, 18, and 22 dag. Data were normalized to the Tubulin (PvTUB) reference gene. Data are mean ± SD from three independent experiments (n = 3). Statistical significance was determined using two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test, p<0.05. Dag: days after germination. Means with the same letter are not significantly different.

References

- Alvarez-Venegas R., Abdallat A. A., Guo M., Alfano J. R., Avramova Z. (2007). Epigenetic control of a transcription factor at the cross section of two antagonistic pathways. Epigenetics 2, 106–113. 10.4161/epi.2.2.4404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asselbergh B., De Vleesschauwer D., Höfte M. (2008). Global switches and fine-tuning-ABA modulates plant pathogen defense. Mol. Plant Microbe. Interact. 21, 709–719. 10.1094/MPMI-21-6-0709 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bari R., Jones J. (2009). Role of plant hormones in plant defence responses. Plant Mol. Biol. 69, 473– 488. 10.1007/s11103-008-9435-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barraza A., Estrada-Navarrete G., Rodriguez-Alegria M. E., Lopez-Munguia A., Merino E., Quinto C., et al. (2013). Down-regulation of PvTRE1 enhances nodule biomass and bacteroid number in common bean. New Phytol. 197, 194–206. 10.1111/nph.12002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barraza B., Luna-Martínez F., Chávez-Fuentes J. C., Álvarez-Venegas R. (2015. a). Expression profiling and down-regulation of three histone lysine methyltransferase genes (PvATXR3h, PvASHH2h, and PvTRX1h) in the common bean. Plant OMICS J. 8, 429–440. [Google Scholar]

- Barraza A., Cabrera-Ponce J. L., Gamboa-Becerra R., Luna-Martínez F., Winkler R., Álvarez-Venegas R. (2015. b). The Phaseolus vulgaris PvTRX1h gene regulates plant hormone biosynthesis in embryogenic callus from common bean. Front. Plant. Sci. 6, 577. 10.3389/fpls.2015.00577 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barraza A., Coss-Navarrete E. L., Vizuet-de-Rueda J. C., Martínez-Aguilar K., Hernández-Chávez J. L., Ordaz-Ortiz J. J., et al. (2018). Down-regulation of PvTRX1h Increases Nodule Number and Affects Auxin, Starch, and Metabolic Fingerprints in the Common Bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.). Plant Sci. 274, 45–58. 10.1016/j.plantsci.2018.05.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baxter A., Mittler R., Suzuki N. (2014). ROS as key players in plant stress signalling. J. Exp. Bot. 65, 1229–1240. 10.1093/jxb/ert375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birkenbihl R. P., Diezel C., Somssich I. E. (2012). Arabidopsis WRKY33 is a key transcriptional regulator of hormonal and metabolic responses toward Botrytis cinerea infection. Plant Physiol. 159, 266–285. 10.1104/pp.111.192641 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borges A., Tsai S. M., Gomes Caldas D. G. (2012). Validation of reference genes for RT-qPCR normalization in common bean during biotic and abiotic stresses. Plant Cell Rep. 31, 827–838. 10.1007/s00299-011-1204-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broughton W. J., Dilworth M. J. (1971). Control of leghaemoglobin synthesis in snake beans. Biochem. J. 125, 1075–1080. 10.1042/bj1251075 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruce T. J. A. (2010). Tackling the threat to food security caused by crop pests in the new millennium. Food Sec. 2, 133–141. 10.1007/s12571-010-0061-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Calvo P., Nelson L. M., Kloepper J. W. (2014). Agricultural uses of plant biostimulants. Plant Soil 383, 3–41. 10.1007/s11104-014-2131-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cárdenas L., Alemán E., Nava N., Santana O., Sánchez F., Quinto C. (2006). Early responses to Nod factors and mycorrhizal colonization in a non-nodulating Phaseolus vulgaris mutant. Planta 223, 746–754. 10.1007/s00425-005-0132-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho L. C., Santos S., Vilela B. J., Amâncio S. (2008). Solanum lycopersicon Mill. and Nicotiana benthamiana L. under high light show distinct responses to anti-oxidative stress. J. Plant Physiol. 165, 1300–1312. 10.1016/j.jplph.2007.04.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conrath U. (2009). “Priming of induced plant defense responses,” in Advances in Botanical Research, vol. 51 . Ed. L. C. Van Loon (London, UK: Elsevier), 361–395. 10.1016/S0065-2296(09)51009-9 [DOI]

- Conrath U. (2011). Molecular aspects of defence priming. Trends Plant Sci. 16, 524–531. 10.1016/j.tplants.2011.06.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Vleesschauwer D., Höfte M. (2009). “Rhizobacteria-induced Systemic Resistance,” in Advances in Botanical Research, vol. 51 . Ed. L. C. Van Loon (London, UK: Elsevier), 223–281. 10.1016/S0065-2296(09)51006-3 [DOI]

- Estrada-Navarrete G., Alvarado-Affantranger X., Olivares J. E., Guillén G., Díaz-Camino C., Campos F., et al. (2007). Fast, efficient and reproducible genetic transformation of Phaseolus spp. by Agrobacterium rhizogenes. Nat. Protocols. 2, 1819–1824. 10.1038/nprot.2007.259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez-Göbel T. F., Deanna R., Muñoz N. B., Robert G., Asurmendi S., Lascano R. (2019). Redox Systemic Signaling and Induced Tolerance Responses During Soybean–Bradyrhizobium japonicum Interaction: Involvement of Nod Factor Receptor and Autoregulation of Nodulation. Front. Plant Sci. 10, 141. 10.3389/fpls.2019.00141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flors V., Ton J., van Doorn R., Jakab G., García-Agustín P., Mauch-Mani B. (2008). Interplay between JA, SA and ABA signalling during basal and induced resistance against Pseudomonas syringae and Alternaria brassicicola. Plant J. 54, 81–92. 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2007.03397.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franche C., Lindström K., Elmerich C. (2009). Nitrogen-fixing bacteria associated with leguminous and non-leguminous plants. Plant Soil 321, 35–59. 10.1007/s11104-008-9833-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gao X., Lu X., Wu M., Zhang H., Pan R., Tian J., et al. (2012). Co-inoculation with rhizobia and AMF inhibited soybean red crown rot: from field study to plant defense-related gene expression analysis. PLoS One 7, e33977. 10.1371/journal.pone.0033977 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glick B. R. (2012). Plant growth-promoting bacteria: mechanisms and applications. Scientifica (Cairo). 2012, 963401. 10.6064/2012/963401 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gouda S., Kerry R. G., Das G., Paramithiotis S., Shin H. S., Patra J. K. (2018). Revitalization of plant growth promoting rhizobacteria for sustainable development in agriculture. Microbiol. Res. 206, 131–140. 10.1016/j.micres.2017.08.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haas D., Défago G. (2005). Biological control of soil-borne pathogens by fluorescent pseudomonads. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 3, 307–319. 10.1038/nrmicro1129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang P. Y., Catinot J., Zimmerli L. (2016). Ethylene response factors in Arabidopsis immunity. J. Exp. Bot. 67, 1231–1241. 10.1093/jxb/erv518 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin L., Mackey D. M. (2017). Measuring Callose Deposition, an Indicator of Cell Wall Reinforcement, During Bacterial Infection in Arabidopsis. Methods Mol. Biol. 1578, 195–205. 10.1007/978-1-4939-6859-6_16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez-Hernández Y., Acosta-Gallegos J. A., Sánchez-García B. M., Martínez Gamiño M. A. (2012). Agronomic traits and Fe and Zn content in the grain of common Rosa de Castilla type bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.). Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Agrícolas. 3, 311–325. http://www.scielo.org.mx/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S2007-09342012000200008. 10.29312/remexca.v3i2.1465 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Juszczak I., Baier M. (2014). Quantification of superoxide and hydrogen peroxide in leaves. Methods Mol. Biol. 1166, 217–224. 10.1007/978-1-4939-0844-8_16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazan K., Manners J. M. (2013). MYC2: the master in action. Mol. Plant 6, 686–703. 10.1093/mp/sss128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim T. W., Hwang J. Y., Kim Y. S., Joo S. H., Chang S. C., Lee J. S., et al. (2005). Arabidopsis CYP85A2, a cytochrome P450, mediates the Baeyer-Villiger oxidation of castasterone to brassinolide in brassinosteroid biosynthesis. Plant Cell 17, 2397–2412. 10.1105/tpc.105.033738 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohler A., Schwindling S., Conrath U. (2002). Benzothiadiazole-induced priming for potentiated responses to pathogen infection, wounding, and infiltration of water into leaves requires the NPR1/NIM1 gene in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 128, 1046–1056. 10.1104/pp.010744 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koiwai H., Nakaminami K., Seo M., Mitsuhashi W., Toyomasu T., Koshiba T. (2004). Tissue-Specific Localization of an Abscisic Acid Biosynthetic Enzyme, AAO3, in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 134, 1697–1707. 10.1104/pp.103.036970 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishna P. (2003). Brassinosteroid-mediated stress responses. J. Plant Growth Regul. 22, 289–297. 10.1007/s00344-003-0058-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li P., Chen L., Zhou Y., Xia X., Shi K., Chen Z., et al. (2013). Brassinosteroids-Induced Systemic Stress Tolerance was Associated with Increased Transcripts of Several Defence-Related Genes in the Phloem in Cucumis sativus. PLoS ONE 8, e66582. 10.1371/journal.pone.0066582 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livak K. J., Schmittgen T. D. (2001). Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 25, 402–408. 10.1006/meth.2001.1262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luna E., Pastor V., Robert J., Flors V., Mauch-Mani B., Ton J. (2011). Callose deposition: a multifaceted plant defense response. Mol. Plant Microbe. Interact. 24, 183–193. 10.1094/MPMI-07-10-0149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luna E., Bruce T. J., Roberts M. R., Flors V., Ton J. (2012). Next-generation systemic acquired resistance. Plant Physiol. 158, 844–853. 10.1104/pp.111.187468 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luna E., López A., Kooiman J., Ton J. (2014). Role of NPR1 and KYP in long-lasting induced resistance by β-aminobutyric acid. Front. Plant Sci. 5, 184. 10.3389/fpls.2014.00184 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Aguilar K., Ramírez-Carrasco G., Hernández-Chávez J. L., Barraza A., Alvarez-Venegas R. (2016). Use of BABA and INA As Activators of a Primed State in the Common Bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.). Front. Plant Sci. 7, 653. 10.3389/fpls.2016.00653 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Viveros O., Jorquera M. A., Crowley D. E., Gajardo G., Mora M. L. (2010). Mechanisms and practical considerations involved in plant growth promotion by rhizobacteria. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 10, 293–319. 10.4067/S0718-95162010000100006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mayo S., Cominelli E., Sparvoli F., González-López O., Rodríguez-González A., Gutiérrez S., et al. (2016). Development of a qPCR Strategy to Select Bean Genes Involved in Plant Defense Response and Regulated by the Trichoderma velutinum - Rhizoctonia solani Interaction. Front. Plant Sci. 7, 1109. 10.3389/fpls.2016.01109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mittler R., Vanderauwera S., Suzuki N., Miller G., Tognetti V. B., Vandepoele K., et al. (2011). ROS signaling: the new wave? Trends Plant Sci. 16, 300–309. 10.1016/j.tplants.2011.03.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osdaghi E., Shams-Bakhsh M., Alizadeh A., Lak M.R., Hamid H.M. (2011). Induction of resistance in common bean by Rhizobium leguminosarum bv. phaseoli and decrease of common bacterial blight. Phytopathol Mediterr 50, 45−54 10.14601/Phytopathol_Mediterr-8524 [DOI]

- Pérez-Montaño F., Alías-Villegas C., Bellogín R. A., del Cerro P., Espuny M. R., Jiménez-Guerrero I., et al. (2014). Plant growth promotion in cereal and leguminous agricultural important plants: from microorganism capacities to crop production. Microbiol. Res. 169, 325–336. 10.1016/j.micres.2013.09.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pieterse C. M., Zamioudis C., Berendsen R. L., Weller D. M., Van Wees S. C., Bakker P. A. (2014). Induced systemic resistance by beneficial microbes. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 52, 347–375. 10.1146/annurev-phyto-082712-102340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pozo M. J., Van Der Ent S., Van Loon L. C., Pieterse C. M. (2008). Transcription factor MYC2 is involved in priming for enhanced defense during rhizobacteria-induced systemic resistance in Arabidopsis thaliana. New Phytol. 180, 511–523. 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2008.02578.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu J.-L., Fiil B.-K., Petersen K., Nielsen H. B., Botanga C. J., Thorgrimsen S., et al. (2008). Arabidopsis MAP kinase 4 regulates gene expression through transcription factor release in the nucleus. EMBO J. 27, 2214–2221. 10.1038/emboj.2008.147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravishankara A. R., Daniel J. S., Portmann R. W. (2009). Nitrous Oxide (N2O): The Dominant Ozone-Depleting Substance Emitted in the 21st Century. Science. 326, 123–125. 10.1126/science.1176985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schindelin J., Arganda-Carreras I., Frise E., Kaynig V., Longair M., Pietzsch T., et al. (2012). Fiji: an open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nat. Methods 9, 676–682. 10.1038/nmeth.2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seo M., Aoki H., Koiwai H., Kamiya Y., Nambara E., Koshiba T. (2004). Comparative Studies on the Arabidopsis Aldehyde Oxidase (AAO) Gene Family Revealed a Major Role of AAO3 in ABA Biosynthesis in Seeds. Plant Cell Physiol. 45, 1694–1703. 10.1093/pcp/pch198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sewelam N., Kazan K., Thomas-Hall S. R., Kidd B. N., Manners J. M., Schenk P. M. (2013). Ethylene response factor 6 is a regulator of reactive oxygen species signaling in Arabidopsis. PLoS One. 8, e70289. 10.1371/journal.pone.0070289 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh V., Roy S., Singh D., Nandi A. K. (2014). Arabidopsis flowering locus D influences systemic-acquired-resistance- induced expression and histone modifications of WRKY genes. J. Biosci. 39, 119–126. 10.1007/s12038-013-9407-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slaughter A., Daniel X., Flors V., Luna E., Hohn B., Mauch-Mani B. (2012). Descendants of primed Arabidopsis plants exhibit resistance to biotic stress. Plant Physiol. 158, 835–843. 10.1104/pp.111.191593 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taté R., Patriarca E. J., Riccio A., Defez R., Iaccarino M. (1994). Development of Phaseolus vulgaris root nodules. Mol. Plant Microbe. Interact. 7, 582–589. 10.1094/MPMI-7-0582 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Timmermann T., Armijo G., Donoso R., Seguel A., Holuigue L., González B. (2017). Paraburkholderia phytofirmans PsJN Protects Arabidopsis thaliana Against a Virulent Strain of Pseudomonas syringae Through the Activation of Induced Resistance. Mol. Plant Microbe. Interact. 30, 215–230. 10.1094/MPMI-09-16-0192-R [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ton J., Mauch-Mani B. (2004). Beta-amino-butyric acid-induced resistance against necrotrophic pathogens is based on ABA-dependent priming for callose. Plant J. 38, 119–130. 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2004.02028.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ton J., Jakab G., Toquin V., Flors V., Iavicoli A., Maeder M. N., et al. (2005). Dissecting the beta-aminobutyric acid-induced priming phenomenon in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 17, 987–999. 10.1105/tpc.104.029728 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ton J., Flors V., Mauch-Mani B.Mauch-Mani., B. (2009). The multifaceted role of ABA in disease resistance. Trends Plant Sci. 14, 310–317. 10.1016/j.tplants.2009.03.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ubertino S., Mundler P., Tamini L. D. (2016). The adoption of sustainable management practices by Mexican coffee producers. Sustain. Agric. Res. 5, 1–12. 10.5539/sar.v5n4p1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Van der Ent S., Van Hulten M., Pozo M. J., Czechowski T., Udvardi M. K., Pieterse C. M., et al. (2009. a). Priming of plant innate immunity by rhizobacteria and beta-aminobutyric acid: differences and similarities in regulation. New Phytol. 183, 419–431. 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2009.02851.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van der Ent S., Van Wees S. C., Pieterse C. M. (2009. b). Jasmonate signaling in plant interactions with resistance-inducing beneficial microbes. Phytochemistry 70, 1581–1588. 10.1016/j.phytochem.2009.06.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Peer R., Niemann G. J., Schippers B. (1991). Induced Resistance and Phytoalexin Accumulation in Biological Control of Fusarium Wilt of Carnation by Pseudomonas sp. Strain WCS417r. Phytopathology 81, 728–734. 10.1094/Phyto-81-728 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vejan P., Abdullah R., Khadiran T., Ismail S., Nasrulhaq Boyce A. (2016). Role of Plant Growth Promoting Rhizobacteria in Agricultural Sustainability-A Review. Molecules 21, E573. 10.3390/molecules21050573 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vessey J. K. (1994). Measurement of nitrogenase activity in legume root nodules: in defense of the acetylene reduction assay. Plant Soil 158, 151–162. 10.1007/BF00009490 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong L., Zhu J. K. (2003). Regulation of abscisic acid biosynthesis. Plant Physiol. 133, 29–36. 10.1104/pp.103.025395 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang J., Kloepper J. W., Ryu C. M. (2009). Rhizosphere bacteria help plants tolerate abiotic stress. Trends Plant Sci. 14, 1–4. 10.1016/j.tplants.2008.10.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerli L., Jakab G., Metraux J. P., Mauch-Mani B. (2000). Potentiation of pathogen-specific defense mechanisms in Arabidopsis by beta -aminobutyric acid. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 97, 12920–12925. 10.1073/pnas.230416897 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang C., Wang X., Zhang F., Dong L., Wu J., Cheng Q., et al. (2017). Phenylalanine ammonia-lyase2.1 contributes to the soybean response towards Phytophthora sojae infection. Sci. Rep. 7, 7242. 10.1038/s41598-017-07832-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng Z., Qamar S. A., Chen Z., Mengiste T. (2006). Arabidopsis WRKY33 transcription factor is required for resistance to necrotrophic fungal pathogens. Plant J. 48, 592–605. 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2006.02901.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials