Abstract

Background: Despite the importance of persons with dementia (PWDs) engaging in advance care planning (ACP) at a time when they are still competent to appoint a surrogate decision maker and meaningfully participate in ACP discussions, studies of ACP in PWDs are rare.

Objective: We conducted an intervention development study to adapt an efficacious ACP intervention, SPIRIT (sharing patient's illness representations to increase trust), for PWDs in early stages (recent Montreal Cognitive Assessment [MoCA] score ≥13) and their surrogates and assess whether SPIRIT could help PWDs engage in ACP.

Design: A formative expert panel review of the adapted SPIRIT, followed by a randomized trial with qualitative interviews, was conducted. Patient–surrogate dyads were randomized to SPIRIT in person (in a private room in a memory clinic) or SPIRIT remote (via videoconferencing from home).

Setting/Subjects: Twenty-three dyads of PWDs and their surrogates were recruited from an outpatient brain health center. Participants completed preparedness outcome measures (dyad congruence on goals of care, patient decisional conflict, and surrogate decision-making confidence) at baseline and two to three days post-intervention, plus a semistructured interview. Levels of articulation of end-of-life wishes of PWDs during SPIRIT sessions were rated (3 = expressed wishes very coherently, 2 = somewhat coherently, and 1 = unable to express coherently).

Results: All 23 were able to articulate their end-of-life wishes very or somewhat coherently during the SPIRIT session; of those, 14 PWDs had moderate dementia. While decision-making capacity was higher in PWDs who articulated their wishes very coherently, MoCA scores did not differ by articulation levels. PWDs and surrogates perceived SPIRIT as beneficial, but the preparedness outcomes did not change pre–post.

Conclusions: SPIRIT engaged PWDs and surrogates in meaningful ACP discussions, but requires testing of efficacy and long-term outcomes.

Keywords: advance care planning, Alzheimer's disease, dementia, end-of-life care, surrogate decision making

Introduction

Alzheimer's disease and related dementias (ADRD) are the sixth leading cause of death in the United States with no effective treatment.1,2 For those with advanced ADRD, intensive or burdensome end-of-life care is common. Nearly 41% undergo at least one intensive intervention (e.g., mechanical ventilation) in the last three months of life.3 Since 2000, the use of mechanical ventilation for Medicare beneficiaries with advanced dementia has doubled with no measurable survival benefit.4 The great challenge to the medical community is to prepare patients and families for complicated end-of-life medical decision making in the context of patients' progressive loss of cognitive function and selfhood.

Despite the importance of persons with dementia (PWDs) engaging in advance care planning (ACP) at a time when they are still competent to appoint a surrogate decision maker and meaningfully participate in ACP discussions,5,6 studies demonstrating how ACP discussions should be conducted with PWDs are rare. Recent systematic reviews of ACP interventions for PWDs7–9 have identified only four ACP interventions involving PWDs and all were set in nursing homes, a setting that may be too late for PWDs to voice their end-of-life preferences adequately. To improve ACP for PWDs and their surrogates (mostly family caregivers), we conducted a behavioral intervention development trial10 to adapt an efficacious ACP intervention, SPIRIT (sharing patient's illness representations to increase trust), for PWDs and their surrogates and assessed whether PWDs could meaningfully participate in the SPIRIT intervention and complete outcome assessment.11

SPIRIT intervention

SPIRIT, a 60-minute, structured psychoeducational intervention provided in a face-to-face interview format, is based on the representational approach to patient education.12 Details on the theoretical underpinnings can be found elsewhere.12 The goal of SPIRIT is to promote preparation for end-of-life decisions for patients and their surrogates. The SPIRIT intervention guide has six steps: (1) assessing illness representation, (2) identifying gaps and concerns, (3) creating conditions for conceptual change, (4) introducing replacement information, (5) summarizing, and (6) setting goals and planning. The interventionist first aims to establish an understanding of the cognitive, emotional, and spiritual aspects of the patient's representation of (ideas about) his/her illness. This understanding enables the interventionist to assist the patient in examining his/her own values related to life-sustaining treatment at the end of life. The interventionist aims to enable the surrogate to understand the patient's illness experiences and values and to be prepared for the responsibility and turmoil that can arise during decision making at the end of life. A Goals-of-Care tool is completed at the end of the session to indicate the patient's preferences. SPIRIT has been extensively evaluated and found to be effective in patients with end-stage renal disease and advanced heart failure and in cardiac surgical patients and their surrogates, such as improving dyad congruence between patients' end-of-life preferences and surrogates' understanding of those preferences, patient decisional conflict, and surrogate decision-making confidence, as well as reducing postbereavement psychological distress for surrogates after the patient's death.13–17

Design and Methods

This study involved two steps: (1) adapting SPIRIT for PWDs and their surrogates and (2) testing the feasibility of the adapted SPIRIT intervention in a randomized trial with qualitative interviews to assess PWD's and surrogate's evaluation of SPIRIT. We assessed whether PWDs can meaningfully participate in the SPIRIT intervention and complete outcome assessment. The study had approval from the Institutional Review Board at Emory University.

SPIRIT modification and formative review by content experts

Guided by Stirman's framework for adapting evidence-based interventions,18 we tailored the SPIRIT intervention guide to be suitable for PWDs, such as the illness trajectory discussion and integrated, enhanced consent techniques19 to the delivery process, such as reducing information load by proceeding in manageable segments/chunks and verifying comprehension before eliciting preferences for goals of care. We also added a web-based face-to-face delivery of SPIRIT through videoconferencing to facilitate wider future implementation (SPIRIT remote). The SPIRIT developers (MS and SW) drafted modifications to the intervention guide and worked iteratively with the rest of the team to complete the initial modifications.

Six experts with no involvement in development of SPIRIT, but with substantial expertise in its theoretical underpinnings, ACP, dementia, and palliative care, were invited to review and provide feedback about the modified intervention guide. They reviewed the guide and rated (1) each activity's relevance to the intended theoretical element, (2) the likely effectiveness in addressing the intervention goal, and (3) appropriateness of language, interview questions for the population, on 4-point scales (e.g., 1 = irrelevant, 4 = essential). We computed the content validity index (CVI; 0–1.0) for each intervention activity. The overall CVIs for relevance to theory, likely effectiveness, and appropriateness were computed and all were >0.8 (≥0.78, excellent for intervention activities20).

Feasibility testing of SPIRIT in person and SPIRIT remote

Setting and participants

Dyads of PWDs and their surrogates were recruited from a brain health center in a large city in Georgia. Inclusion criteria for PWDs were (1) dementia diagnosis; (2) recent Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) score ≥13 (a threshold for capacity to complete advance directives21); (3) able to understand and speak English; and (4) decision-making capacity to consent to a low-risk study: a score ≥9 on the University of California, San Diego Brief Assessment of Capacity to Consent (UBACC). The 10-item UBACC (each item score ranges from 0 to 2) had been validated in people with ADRD22 and required under five minutes to administer.

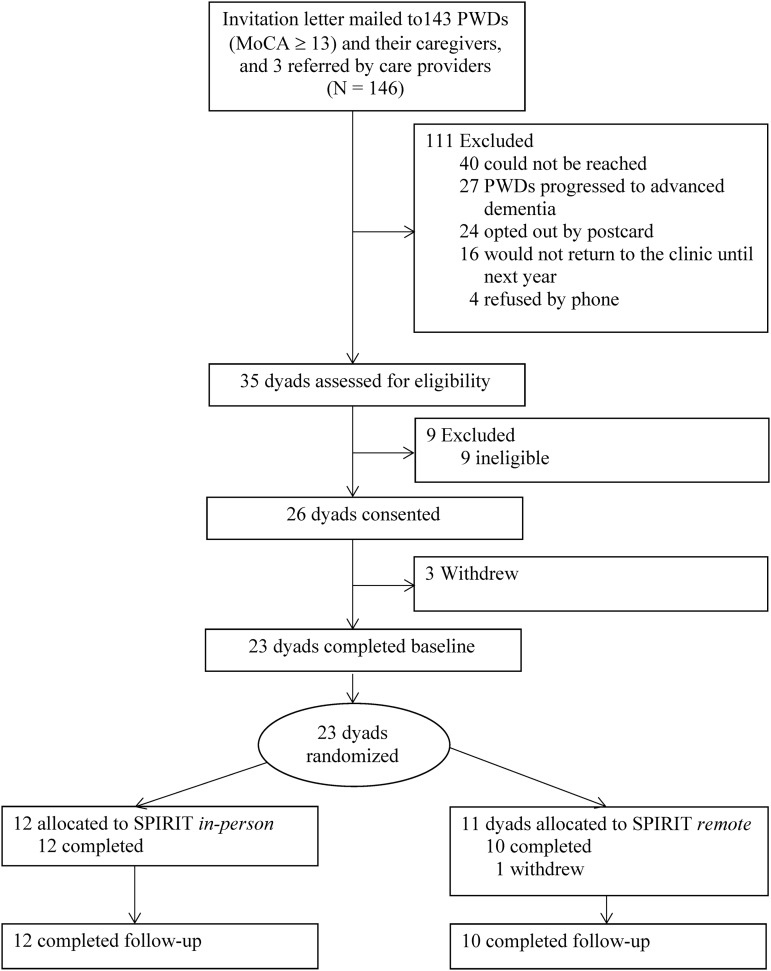

A study team member approached 35 potentially eligible PWDs and their family caregivers in the clinic during their visit (Fig. 1). Surrogate eligibility criteria included (1) 18 years or older; (2) chosen by the PWD; (3) have access to a computer and Internet connectivity in a private setting; and (4) understand and speak English. Nine dyads were excluded based on the UBACC criterion, and 26 dyads provided written consents. Of the 35 approached, 23 dyads completed baseline measures and were randomized. Each member of the dyad received a $30 gift card at study completion.

FIG. 1.

Participant progress in the study.

Randomization and intervention

Group assignments were generated before enrollment and concealed in sequentially numbered opaque envelops opened after the dyad completed baseline measures. Dyads were randomly assigned (1:1 ratio) to SPIRIT in person or SPIRIT remote using random block sizes of 5.

One interventionist (social worker) trained for both modalities conducted all intervention sessions. SPIRIT in-person sessions were conducted in a private room in the clinic. For SPIRIT remote, we used Zoom, a videoconferencing platform. We sent the dyads in SPIRIT remote the necessary equipment (e.g., webcam and microphone) as needed. Detailed instructions were sent to the surrogate one to two weeks before the scheduled SPIRIT session. A research assistant called the surrogate to walk through the instructions and problem solve as needed. Dyads in SPIRIT remote participated from their homes. All sessions were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim.

Measurement and data collection

At baseline, PWDs and surrogates independently completed a sociodemographic profile and measures of preparedness outcomes (dyad congruence, patient decisional conflict, and surrogate decision-making confidence) over the telephone. Participants completed the preparedness outcome measures again, followed by a semistructured interview, two to three days after the intervention. A noninterventionist performed all post-intervention assessments.

Dyad congruence was assessed using the Goals-of-Care tool16 modified to include two scenarios relevant to ADRD. In the first, the PWD has progressed to advanced dementia and develops a severe infection such as pneumonia and is admitted to a hospital; the medical team believes recovery would be unlikely and continuing life-sustaining treatment would no longer be beneficial. There were three response options: “The goals of care should be focused on delaying my death,” “The goals of care should be focused on my comfort and peace,” and “I am not sure.” In the second scenario, the PWD has progressed to advanced dementia and develops a severe infection. The surrogate is being asked whether the PWD should be taken to an emergency department (ED), which will lead to hospitalization with life-sustaining treatments. PWDs and surrogates completed this tool independently and their responses were then compared to determine dyad congruence—either congruent in both scenarios or incongruent. If both members of the dyad endorsed “I am not sure,” they were considered incongruent.

Patient decisional conflict was measured using the 13-item Decisional Conflict Scale, a validated measure in the context of end-of-life decision making13; higher scores indicate greater difficulty in weighing benefits and burdens of life-sustaining treatments and decision making (1 = strongly agree, 5 = strongly disagree; Cronbach's α = 0.80–0.9314,16). In the present study, Cronbach's alpha ranged from 0.80 to 0.83.

Surrogate decision-making confidence was measured using the 5-item Decision-Making Confidence Scale (Cronbach's α = 0.81–0.9014,16); higher scores reflect greater comfort in performing as a surrogate (0 = not confident at all, 4 = very confident). With the study sample, Cronbach's alpha ranged from 0.65 to 0.67.

Feasibility of SPIRIT and outcome assessment with PWDs

We tracked the number of incomplete or interrupted sessions, duration, and any technical difficulties during SPIRIT remote sessions. Using a quantitizing technique of qualitative data analysis,23 two authors (MK and HK) reviewed SPIRIT transcripts. They independently rated the level of PWD's articulation of end-of-life care preferences on a 3-point scale (3 = expressed wishes very coherently, 2 = somewhat, and 1 = unable to express wishes coherently). The two authors also reviewed the transcripts of interviews with PWDs and rated their level of recollection of the SPIRIT session on a 3-point scale (3 = recalled participation in SPIRIT and some details, 2 = vague recollection of SPIRIT, and 1 = no recollection of SPIRIT). Inter-rater reliability (percent agreement) was 91.3% for articulation of wishes and 95.5% for recollection of SPIRIT, and discrepancies were resolved by discussion and reaching consensus. We also tracked measures and items that PWDs expressed difficulty understanding or refused to answer.

Acceptability and perceived impact of SPIRIT

Using a semistructured interview guide, a research assistant conducted a 10- to 15-minute interview with each member of the dyad regarding their experience with SPIRIT, perceived impact, facets of the intervention that the participant found helpful or unhelpful, and suggestions for improvement. Interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim.

Data analyses

Preliminary effect sizes of changes in preparedness outcomes were calculated as differences between pre- and post-intervention mean scores for continuous variables or risk ratios of pre- and postcongruence outcomes within each group. Due to the small sample size, we calculated 95% bootstrap confidence intervals of the change scores/risk ratios. The associations between ratings of PWD's articulation of wishes and recollection of SPIRIT and MoCA and UBACC scores were each examined using Kruskal–Wallis tests. As this was a feasibility study, a formal sample size calculation was not performed. All analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics 24.

Because one dyad withdrew during the SPIRIT session, 44 transcripts (22 PWDs and 22 surrogates) were included in the data analysis. Of the 22 PWD transcripts, 13 contained responses to all interview questions (9 did not recall participating in SPIRIT). Data were analyzed using conventional content analysis techniques24 without preconceived categories. Two authors (MK and HK) coded the data independently, compared codes, and reconciled any differences. Then, codes were grouped into main and subcategories that represented aspects of the participant's experiences with SPIRIT. ATLAS.ti.7 (GmbH, Berlin) was used for qualitative data management.

Results

Sample characteristics

Mean age of PWDs was 74.2 (SD = 7.6) years (Table 1) and they were mostly non-Hispanic white (n = 17, 73.9%). On average, they were diagnosed with dementia three years before enrollment. Fourteen (60.9%) had moderate dementia (MoCA = 13–17). Most surrogates were female (n = 15, 65.2%) and spouses (n = 17, 73.9%).

Table 1.

Sample Characteristics by Treatment Group (N = 23)

| SPIRIT in person (n = 12) | SPIRIT remote (n = 11) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | PWD | Surrogate | PWD | Surrogate |

| Age in years, M (SD) | 73.7 (7.5) | 63.1 (11.8) | 74.7 (7.9) | 69.7 (9.8) |

| Female, n (%) | 7 (58.3) | 8 (66.7) | 5 (41.7) | 7 (63.6) |

| Years of formal education completed | 15.4 (2.5) | 16.6 (2.7) | 15.2 (3.0) | 16.3 (2.3) |

| White (non-Hispanic) | 9 (75.0) | 9 (75.0) | 8 (72.7) | 9 (81.8) |

| Relationship to PWD | ||||

| Spouse/partner | — | 8 (66.7) | — | 9 (81.8) |

| Child | — | 4 (33.3) | — | 2 (18.2) |

| Have had a close family member or friend die | 12 (100.0) | 12 (100.0) | 10 (90.9) | 10 (90.9) |

| Had a discussion with PWD about his/her wishes | ||||

| With PWD alone only | — | 7 (58.3) | — | 7 (63.6) |

| With PWD and his/her doctor | — | 4 (33.3) | — | 4 (36.4) |

| Dementia type | ||||

| Alzheimer's disease | 10 (83.3) | — | 8 (72.7) | — |

| Lewy bodies | 2 (16.7) | — | 0 | — |

| Vascular | 0 | — | 1 (9.1) | — |

| Frontotemporal | 0 | — | 1 (9.1) | — |

| Mixed | 0 | — | 1 (9.1) | — |

| Months since dementia diagnosis, M (SD) | 38.8 (27.8) | — | 31.1 (17.0) | — |

| Recent global cognitive function (MoCA score), M (SD), range | 17.1 (2.9) (14–25) | — | 18.3 (5.0) (13–25) | — |

| Months since last MoCA | 4.7 (6.2) (0–22) | — | 8.5 (9.5) (0–32) | — |

| Top 3 comorbid conditions, n (%) | ||||

| Hypertension | 7 (58.3) | — | 6 (54.6) | — |

| Depression | 6 (50.0) | — | 6 (54.5) | — |

| Diabetes | 2 (16.7) | — | 3 (27.3) | — |

| UBACC score at enrollment, M (SD), range | 13.1 (2.0) (10–16) | — | 13.3 (2.3) (9–16) | — |

MoCA, Montreal Cognitive Assessment; PWD, person with dementia; SD, standard deviation; SPIRIT, Sharing Patient's Illness Representations to Increase Trust; UBACC, University of California San Diego Brief Assessment of Capacity to Consent.

Preparedness outcomes

At baseline, dyad congruence was high (17 dyads in total, 73.9%), patient decisional conflict (M [SD] = 1.74 [0.42]) was low (<2.0), and surrogate decision-making confidence (M [SD] = 3.78 [0.31]) was high (>2.0). These numbers did not change at post-intervention assessment in either treatment group (Table 2).

Table 2.

Preparedness Outcomes by Treatment Group

| Outcome variable | SPIRIT in person (n = 12) | SPIRIT remote (n = 10)a |

|---|---|---|

| Dyad congruence,bn (%) | ||

| Baseline | 7 (58.33) | 9 (90.90) |

| Post-intervention | 8 (66.67) | 8 (80.00) |

| Risk ratioc (95% CI) | 1.14 (0.56–2.33) | 0.89 (0.55–1.33) |

| Patient Decisional Conflict Scale (range 1–5), M (SD) | ||

| Baseline | 1.81 (0.42) | 1.66 (0.42) |

| Post-intervention | 1.82 (0.59) | 1.60 (0.43) |

| Mean difference (95% CI) | −0.001 (−0.22 to 0.22) | −0.007 (−0.25 to 0.21) |

| Surrogate Decision-Making Confidence Scale (range 0–4), M (SD) | ||

| Baseline | 3.73 (0.41) | 3.84 (0.15) |

| Post-intervention | 3.70 (0.46) | 3.94 (0.19) |

| Mean difference (95% CI) | 0.03 (−0.27 to 0.42) | −0.10 (−0.20 to 0.00) |

Higher patient Decisional Conflict Scale scores indicate greater difficulty in decision making. Higher surrogate decision-making confidence scores indicate greater confidence.

One dropout.

Number of dyads who were congruent on goals of care.

Risk ratio = an estimate of incidence of congruence at post-intervention over baseline.

CI, confidence interval.

Feasibility of SPIRIT and outcome assessment with PWDs

One SPIRIT remote session was incomplete because the surrogate became protective of the PWD and wanted to stop the session when the Goals-of-Care document was reviewed. Two SPIRIT remote sessions encountered ongoing audio problems. SPIRIT sessions averaged 100.5 minutes (SD = 16.7; range 51–122). Duration did not differ by modality or by MoCA or UBACC scores of PWDs.

All 23 PWDs were able to articulate their values and end-of-life wishes somewhat or very coherently. While MoCA scores did not differ by articulation level, the UBACC scores did, Kruskal–Wallis H = 5.57, df = 1, p = 0.02, with a mean rank score of 3.50 for a rating of 2 (somewhat coherent, n = 3) and 13.28 for a rating of 3 (very coherent, n = 20).

Nine PWDs could not recall participating in SPIRIT, stating, for example, “It was about riding a bicycle.” Nonetheless, the levels of articulation of wishes during the SPIRIT session for seven of these nine PWDs were rated 3. MoCA scores differ by the level of recollection of SPIRIT, Kruskal–Wallis H = 6.36, df = 2, p = 0.04, with a mean rank score of 7.56 for a rating of 1 (no recollection, n = 9), 12.40 for a rating of 2 (remembered SPIRIT vaguely, n = 5), and 15.38 (remembered details, n = 8). However, UBACC scores were similar. Four PWDs at baseline and 6 at post-intervention expressed difficulty choosing a response option in the Decisional Conflict Scale.

Participants' evaluation of SPIRIT

PWDs who could provide feedback on their SPIRIT sessions stated that they felt comfortable during the session and that it felt good to express feelings and preferences. However, four PWDs expressed emotional difficulty in confronting death, and two PWDs said they became physically tired toward the end of the session. Nearly every surrogate described the experiences with SPIRIT as positive and comprehensive, yet intense and emotional. Surrogates particularly appreciated the opportunity for themselves and PWDs to express their feelings and have open communication about dementia and end of life. The most frequently stated benefit of SPIRIT was helping the dyad being on the same page. The most challenging part for surrogates was the emotional difficulty visualizing the PWD's end of life.

Six PWDs and eight surrogates said the session was long, and one surrogate said it was short. While most participants suggested no change to SPIRIT, a few recommendations from PWDs and surrogates included reducing interview questions that seemed redundant, having multiple sessions over time, and slowing down with more pauses. While two surrogates commented on advantages of SPIRIT remote, including no travel and making the discussion more personal, two others stated that dealing with computer issues in setting up the videoconference was a nuisance.

Discussion

The adapted SPIRIT intervention appears to have enabled PWDs included in the study to engage in an ACP discussion and to promote authenticity of exchanges about experiences surrounding illness and values. Meaningful ACP conversations were possible even for those with moderate dementia and limited decision-making capacity. We believe this was possible because SPIRIT was focused on exploring beliefs and values of PWDs and their surrogates and did not demand the ability to process factually intensive information, nor did it rely heavily on short-term memory. In the absence of ACP interventions with PWDs before they are placed in a nursing home, this is an important finding because Hirschman et al.25 found that as cognitive impairment of PWDs becomes advanced, family members use the best interest standard (what a reasonable person would do) more often than substituted judgment (what my loved one would have wanted), and the primary reason for using the best interest standard was that there had been no previous discussion about the PWD's preferences.26

Our feasibility data also suggest that decision-making capacity may be the more critical mental faculty, rather than global cognitive function, in ACP discussions especially for eliciting end-of-life wishes and preferences. However, the relationships among ability of PWDs to articulate their wishes, cognitive functioning, and decision-making capacity need to be further evaluated.

We set the outcome assessment to occur soon (two to three days) after the intervention rather than two weeks as in earlier SPIRIT studies to increase the likelihood that PWDs could recall the SPIRIT session and give us reliable feedback. Obtaining feedback immediately after the session was not feasible because of fatigue and subject burden. Nine PWDs could not remember having the SPIRIT session, but this should not be interpreted as meaning that SPIRIT was of less value for those dyads because all PWDs conveyed their wishes to their surrogates coherently during the session.

Although several PWDs and surrogates reported that confronting death was emotionally challenging, only one session was incomplete. Overall, SPIRIT was well received by both PWDs and their surrogates regardless of its modality. However, as noted, the sessions were long. The main reasons for the longer duration compared with earlier SPIRIT studies (100 minutes vs. 82 minutes) were that the interventionist was required to speak slowly, repeat questions for the PWD, and ask clarifying questions whenever the response of the PWD was vague. Furthermore, PWDs often paused to come up with words or collect their thoughts. Although the intervention could be broken into two sessions, this would not likely be beneficial due to limited or absent short-term memory of PWDs.

There are several study limitations. Because we aimed to test the feasibility of SPIRIT (not efficacy), the sample was small, and we used a randomized design to minimize potential biases on the preparedness outcomes rather than to conduct between-group efficacy comparisons. Additionally, the sample was homogeneous, consisting mostly of well-educated whites. On preparedness outcomes, we observed ceiling effects resulting in no pre–post change. We did not exclude those who had had an end-of-life discussion before enrollment because prior engagement in such a discussion was not associated with outcomes in prior SPIRIT trials. Our sample may be unusual because participants were recruited from a clinic in which providers are highly proactive about ACP. The surrogate Decision-Making Confidence Scale's Cronbach's alpha was low, which warrants further evaluation in this population. Finally, telephone-based data collection was used to reduce subject burden, but it might be challenging for PWDs. Future studies should include a trial with three groups to evaluate the effects of SPIRIT in person and SPIRIT remote compared with a control group in a larger diverse sample targeting dyads who have not had an end-of-life discussion or completed an advance directive.

Acknowledgment

This work was supported by the National Institute on Aging, National Institutes of Health [R01AG0577714 to M.S.]. ClinicalTrials.gov NCT03311711, Registered 10/12/2017.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1. McKhann GM, Knopman DS, Chertkow H, et al. : The diagnosis of dementia due to Alzheimer's disease: Recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer's Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement 2011;7:263–269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Green C, Zhang S: Predicting the progression of Alzheimer's disease dementia: A multidomain health policy model. Alzheimers Dement 2016;12:776–785 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Mitchell SL, Teno JM, Kiely DK, et al. : The clinical course of advanced dementia. N Engl J Med 2009;361:1529–1538 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Teno JM, Gozalo P, Khandelwal N, et al. : Association of increasing use of mechanical ventilation among nursing home residents with advanced dementia and intensive care unit beds. JAMA Intern Med 2016;176:1809–1816 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Tay SY, Davison J, Jin NC, Yap PL: Education and executive function mediate engagement in advance care planning in early cognitive impairment. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2015;16:957–962 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Cheong K, Fisher P, Goh J, Ng L, Koh HM, Yap P: Advance care planning in people with early cognitive impairment. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2015;5:63–69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bryant J, Turon H, Waller A, Freund M, Mansfield E, Sanson-Fisher R: Effectiveness of interventions to increase participation in advance care planning for people with a diagnosis of dementia: A systematic review. Palliat Med 2019;33:262–273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sellars M, Chung O, Nolte L, et al. : Perspectives of people with dementia and carers on advance care planning and end-of-life care: A systematic review and thematic synthesis of qualitative studies. Palliat Med 2019;33:274–290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Robinson L, Dickinson C, Rousseau N, et al. : A systematic review of the effectiveness of advance care planning interventions for people with cognitive impairment and dementia. Age Ageing 2012;41:263–269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Onken LS, Carroll KM, Shoham V, Cuthbert BN, Riddle M: Reenvisioning clinical science: Unifying the discipline to improve the public health. Clin Psychol Sci 2014;2:22–34 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Song MK, Ward SE, Hepburn K, Paul S, Shah RC, Morhardt DJ: SPIRIT advance care planning intervention in early stage dementias: An NIH stage I behavioral intervention development trial. Contemp Clin Trials 2018;71:55–62 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Donovan HS, Ward SE, Song MK, Heidrich SM, Gunnarsdottir S, Phillips CM: An update on the representational approach to patient education. J Nurs Scholarsh 2007;39:259–265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Song MK, Kirchhoff KT, Douglas J, Ward SE, Hammes BJ: A randomized, controlled trial to improve advance care planning among patients undergoing cardiac surgery. Med Care 2005;43:1049–1053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Song MK, Ward SE, Happ MB, et al. : Randomized controlled trial of SPIRIT: An effective approach to preparing African American dialysis patients and families for end-of-life. Res Nurs Health 2009;32:260–273 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Song MK, Donovan HD, Piraino B, et al. : Effects of an intervention to improve communication about end-of-life care among African Americans with chronic kidney disease. Appl Nurs Res 2010;23:65–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Song MK, Ward SE, Fine JP, et al. : Advance care planning and end-of-life decision making in dialysis: A randomized controlled trial targeting patients and their surrogates. Am J Kidney Dis 2015;66:813–822 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Metzger M, Song MK, Devane-Johnson S: LVAD patients' and surrogates' perspectives on SPIRIT-HF: An advance care planning discussion. Heart Lung 2016;45:305–310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Stirman SW, Miller CJ, Toder K, Calloway A: Development of a framework and coding system for modifications and adaptations of evidence-based interventions. Implement Sci 2013;8:65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Mittal D, Palmer BW, Dunn LB, et al. : Comparison of two enhanced consent procedures for patients with mild Alzheimer disease or mild cognitive impairment. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2007;15:163–167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kassam-Adams N, Marsac ML, Kohser KL, Kenardy JA, March S, Winston FK: A new method for assessing content validity in model-based creation and iteration of eHealth interventions. J Med Internet Res 2015;17:e95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Gregory R, Roked F, Jones L, Patel A: Is the degree of cognitive impairment in patients with Alzheimer's disease related to their capacity to appoint an enduring power of attorney? Age Ageing 2007;36:527–531 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Seaman JB, Terhorst L, Gentry A, Hunsaker A, Parker LS, Lingler JH: Psychometric properties of a decisional capacity screening tool for individuals contemplating participation in Alzheimer's disease research. J Alzheimer Dis 2015;46:1–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Sandelowski M: Real qualitative researchers do not count: The use of numbers in qualitative research. Res Nurs Health 2001;24:230–240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hsieh HF, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res 2005;15:1277–1288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hirschman KB, Xie SX, Feudtner C, Karlawish JH: How does an Alzheimer's disease patient's role in medical decision making change over time? J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol 2004;17:55–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hirschman KB, Kapo JM, Karlawish JH: Why doesn't a family member of a person with advanced dementia use a substituted judgment when making a decision for that person? J Geriatr Psychiatry 2006;14:659–667 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]