Abstract

Background

Malignant pleural effusion (MPE) is common and diagnosis is often problematic. A cancer ratio (serum lactate dehydrogenases: pleural adenosine deaminase ratio) has been proposed for diagnosing MPE. However, the usefulness of this “cancer ratio” and the clinical‐radiological criteria for diagnosing MPE has not been clearly determined to date. The aim of this study was to assess the performance of those parameters in the diagnosis of MPE.

Methods

We analyzed 240 patients including 120 with MPE and 120 with non‐MPE (93 tuberculous and 27 parapneumonic). Patients were divided into two groups: MPE and non‐MPE (eg, tuberculous and parapneumonic). We constructed two predictive models to assess the probability of MPE: (a) clinical‐radiological data only and (b) a combination of clinical‐radiological data, the cancer ratio, and the carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA). The performances of the predictive models were assessed using receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves and by examining the calibration.

Results

The area under the ROC curves for model 1 and model 2 were excellent, 0.936 and 0.998, respectively. The overall diagnostic accuracies for model 1 and model 2 were 87.5% and 98.8%, respectively.

Conclusion

The results confirm that both models achieved a high diagnostic accuracy for MPE; however, model 2 was superior with the addition of its simplicity of use in daily practice. This model should be applied to determine which patients with a pleural effusion of unknown origin would not benefit from further invasive procedures.

Keywords: diagnosis, lactate dehydrogenases, logistic models, malignant, pleural effusion

1. INTRODUCTION

Malignant pleural effusion (MPE), tuberculous pleural effusion, and parapneumonic pleural effusion are the most common aetiologies of an exudative pleural effusion in clinical practice.1 The differential diagnosis of MPE and non‐MPE (eg, tuberculous and parapneumonic) is very difficult and none of the current routine tests diagnose MPE adequately. A final diagnosis cannot be reached in 20% of cases.1 In MPE, the diagnostic yield of pleural fluid cytology has been found to be 66%, whereas that of pleural biopsy has been found to be 46% and a combination of both procedures has been found to have a diagnostic yield of 73%.2 Recently, many more advanced assays have been developed to diagnose MPE, such as carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), carbohydrate antigen 153, carbohydrate antigen 125, and cyfra 21‐1. However, these tumor markers are poor predictors for the diagnosis of MPE.3, 4, 5, 6 Further, there are limited biochemical markers for the diagnosis of MPE. The clinical decision on whether to perform future invasive procedures in the case of pleural exudative, such as pleuroscopy, should be based on more evidence.

Thus, the objective of the present study was to develop a predictive model that applied simple clinical and analytical parameters, with the goal of discriminating between MPE and non‐MPE.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

We analyzed the case records of patients who had a diagnosis of MPE or non‐MPE (eg, tuberculous and parapneumonic) in Wenzhou Central Hospital, China, from January 2012 to June 2018. Ethics committee approval was obtained prior to the commencement of the study. Patients in whom pleural effusion was secondary to heart failure, pericardial disease, trauma, or pulmonary embolism were excluded from the analysis. Data collected at the time of admission and before any medical treatment occurred were considered for analysis. Basic demographic, clinical and bio‐marker data were collected within 24 hours of hospitalization. Patients were divided into two groups: MPE and non‐MPE. MPE was defined by the presence of malignant cells from pleural effusion cytology or histopathology. Tuberculous was defined as caseating granulomatous inflammation present in a biopsy or a positive acid‐fast bacilli stain or mycobacterial culture of pleural effusion. Parapneumonic was defined as abscess, bacterial pneumonia, or bronchiectasis. The lactate dehydrogenase (LDH, U/L) and adenosine deaminase (ADA, U/L) were analyzed using an Olympus AU5400 analyzer (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). CEA was determined using electrochemiluminescence analyzer (MODULAR ANALYTICS Cobas E‐170,Roche Diagnostics; Mannheim, Germany). And CX 21 Olympus binocular microscope was used for cell classification.

We used SPSS 23.0 and R software programs for statistical analysis.7 R is freely available at https://cran.rproject.org. Continuous variables are expressed as means (SD) or medians (P25, P75) and were compared using an unpaired Student's t test or the nonparametric Mann‐Whitney test. Categorical variables are presented as counts and percentages and were compared using chi‐square statistics or Fisher's exact test.

Candidate variables with a P value <0.15 after univariate analysis were included in the regression model. Then, logistic regression analysis was performed. The CEA and cancer ratio (serum lactate dehydrogenases (LDH): pleural adenosine deaminase (ADA) ratio) results showed skewed distributions. Thus, these variables were loge‐transformed for multivariate analysis. We constructed two predictive models to assess the probability of MPE: (a) clinical‐radiological data only and (b) a combination of clinical‐radiological data, the cancer ratio and CEA. Then, the performances of both predictive models were assessed using receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves and measurements of calibration and classification accuracy.8 The Hosme‐Lemeshow goodness‐of‐fit test was examined to assess calibration. A P value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. RESULTS

In total, data from 120 patients with MPE and 120 patients with non‐MPE (93 tuberculous and 27 parapneumonic) were obtained retrospectively. The origins of the MPEs are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Origin of malignant pleural effusions

| Origin | n | Origin | n |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lung | 96 | Mesothelioma | 1 |

| Stomach | 4 | Cholangiocellular | 3 |

| Breast | 3 | Ileocecal pseudomyxoma | 1 |

| Prostate | 1 | Unknown origin | 10 |

| Uterus | 1 | Ttotal | 120 |

Table 2 shows the clinical‐radiological and analytical characteristics of the patients. There were no significant differences between the two groups regarding whether the patients were smokers or not. MPE patients were significantly older (P < 0.01), had a higher prevalence of dyspnoea (P < 0.01), a higher prevalence of clinical symptoms for greater than 30 days (P < 0.01), a more serosanguinous appearance of pleural effusion (P < 0.01), more X‐ray/CT images suggestive of malignancy (P < 0.01), less chest pain (P < 0.01), and a lower prevalence of fever and general syndrome (defined as asthenia, anorexia, and loss of weight) (P < 0.01) than non‐MPE patients. CEA, serum LDH, and the cancer ratio (serum LDH: pleural ADA ratio) were significantly higher in MPE patients than that in non‐MPE patients (all P < 0.01). In contrast, polymorphonuclears, serum proteins, pleural proteins, serum LDH, and pleural effusion ADA were much lower (all P < 0.01).

Table 2.

Clinical‐radiological and analytical characteristics of patients

| Variable | MPE (N = 120) | Non‐MPE(N = 120) | Statistics | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age(y) | 69.7 ± 13.8 | 39.9 ± 17.8 | t = −14.5 | <0.01 |

| Males, n% | 50 (50.0%) | 94 (78.3%) | χ 2 = 20.9 | <0.01 |

| Smoking, n(%) | 41 (34.2%) | 49 (40.8%) | χ 2 = 1.1 | 0.29 |

| Clinical symptoms>30 days | 82 (68.3%) | 25 (20.8%) | χ 2 = 54.8 | <0.01 |

| Dyspnoea | 96 (80.0%) | 67 (55.8%) | χ 2 = 16.1 | <0.01 |

| Chest pain | 33 (27.5%) | 84 (70.0%) | χ 2 = 43.4 | <0.01 |

| General syndrome* | 87 (72.5%) | 66 (55.0%) | χ 2 = 8.0 | <0.01 |

| Fever | 25 (20.8%) | 71 (59.2%) | χ 2 = 36.7 | <0.01 |

| X‐ray/CT compatible with malignancy** | 100 (83.3%) | 28 (23.3%) | χ 2 = 86.8 | <0.01 |

| Serosanguinous PF | 51 (42.5%) | 13 (10.8%) | χ 2 = 30.7 | <0.01 |

| PF polymorphonuclears (%) | 8 (3‐19) | 16 (6‐31) | z = −3.98 | <0.01 |

| PF lymphocytes (%) | 51 (35‐69) | 76 (45‐87) | z = −4.61 | <0.01 |

| PF proteins(g/dL) | 46.7 ± 13.0 | 50.3 ± 6.9 | t = 2.6 | <0.01 |

| Serum proteins(g/L) | 62.1 ± 7.3 | 65.7 ± 6.8 | t = 3.9 | <0.01 |

| pLDH(U/L) | 322 (239‐554) | 480 (320‐797) | z = −3.95 | <0.01 |

| pADA(U/L) | 9.0 (5.9‐13.4) | 49 (30‐ 64) | z = −12.04 | <0.01 |

| pCEA(μg/L) | 105.1 (6.6‐645.0) | 0.9 (0.6‐1.4) | z = −11.46 | <0.01 |

| sLDH(U/L) | 218.5 (169‐327) | 171 (148‐199) | z = −5.57 | <0.01 |

| cancer ratio | 26.7 (17.7‐ 37.0) | 3.4 (2.6‐6.5) | z = −12.27 | <0.01 |

pLDH, pleural lactate dehydrogenase; pADA, pleural adenosine deaminase; pCEA, pleural carcinoembryonic antigen; sLDH, serum lactate dehydrogenase; cancer ratio, serum LDH: pleural ADA ratio; MPE, malignant pleural effusion; PF, pleural fluid.

Defined as asthenia, anorexia, and loss of weight.

Presence of lung masses, pulmonary atelectasis, or mediastinal lymph node disease. Quantitative data are expressed as mean (SD) or medians (P25, P75).

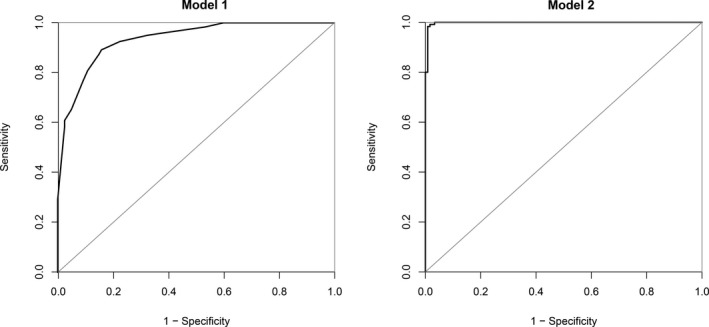

Logistic regression analysis was performed to predict the diagnosis of MPE (Table 3). Better classification was shown in model 2 when prevalence of clinical symptoms for greater than 30 days was combined with chest pain, serosanguinous appearance, X‐ray/CT images suggestive of malignancy, CEA and cancer ratio for the prediction of MPE. Compared to model 1 (area under the curve (AUC) = 0.936), the discrimination capacity of model 2 (AUC = 0.998, P < 0.001) was higher for the diagnosis of MPE than that for non‐MPE. The bootstrap technique showed no optimism. The AUCs of model 1 and model 2 were 0.933 and 0.997, respectively.

Table 3.

Logistic regression models for diagnosing malignant etiology in pleural effusion

| Model 1 | Model 2 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficients (SE) | OR (95%CI) | P value | Coefficients (SE) | OR (95%CI) | P value | |

| X‐ray/CT (1 = yes) | 2.90 (0.45) | 18.19 (7.47,44.33) | <0.001 | 4.21 (1.69) | 67.34 (2.5,1841) | 0.013 |

| Clinical symptoms >30 days | 1.97 (0.44) | 7.18 (3.04,16.99) | <0.001 | 2.81 (1.45) | 1.65 (1.0,284) | 0.053 |

| Serosanguinous PF | 2.83 (0.55) | 16.90 (5.73,49.85) | <0.001 | 1.77 (1.36) | 5.85 (0.43,80.01) | 0.186 |

| Chest pain | −2.34 (0.45) | 0.10 (0.04,0.23) | <0.001 | −2.96 (1.43) | 0.05 (0.003,0.85) | 0.052 |

| Ln(pCEA)μg/L | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | 1.81 (0.63) | 6.09 (1.78,20.85) | 0.004 |

| Ln(cancer ratio) | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | 3.41 (0.97) | 30.29 (4.5,202) | <0.001 |

SE, standard error; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; HL, Hosmer‐Lemeshow; X‐ray/CT, images in chest X‐ray/CT suggestive of malignancy; pCEA, pleural carcinoembryonic antigen. cancer ratio, serum LDH: pleural ADA ratio

Model 1 included chest pain, serosanguinous appearance, X‐ray/CT and clinical symptoms >30 days. Intercept = −2.06; HL, P = 0.779, R 2 = 0.709, AUC = 0.936#

Model 2 included chest pain, serosanguinous appearance, X‐ray/CT, clinical symptoms >30 days, CEA and cancer ratio. Intercept = −13.05; HL, P = 1, R 2 = 0.963, AUC = 0.998. #, P < 0.001 for AUC comparisons with Model 2.

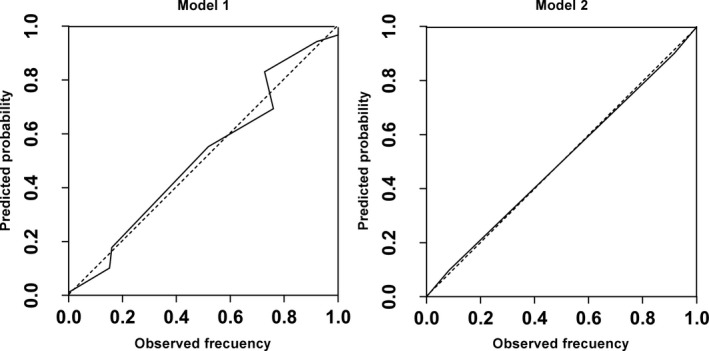

The ROC curves and calibration data are shown in Figure 1 and Figure 2, respectively. The agreement between the predicted probabilities and observed frequencies was excellent.

Figure 1.

ROC (receiver operating characteristics) of the two models studied

Figure 2.

Calibration of the two predictive models studied

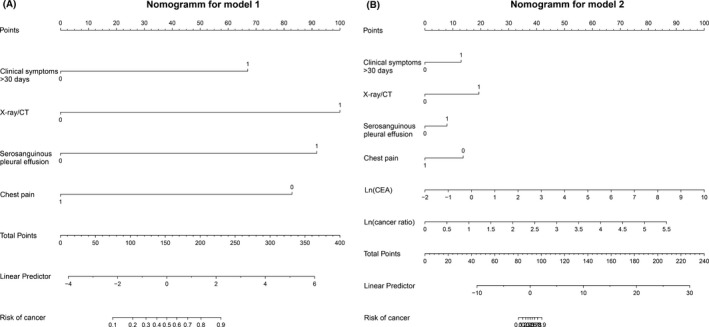

Nomograms for model 1 and model 2 are displayed in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Nomograms of the two models studied (Figure A, Model 1; Figure B, Model 2)

The estimated probability of classifying an individual as having an MPE is as follows:

Pr (MPE) = eLP/(1 + eLP),

where, e = 2.718282.

LP (linear predictor) = −2.06 + 2.90 (X‐ray/CT) + 2.83 (serosanguinous appearance) ‐ 2.34 (chest pain) + 2.90 (clinical symptoms>30 days)

for model 1, and.

LP (linear predictor) = −13.05 + 4.21(X‐ray/CT) + 1.77 (serosanguinous appearance) + 2.81 (clinical symptoms>30 days) ‐ 2.96 (chest pain) + 3.78 lnCEA +3.41 ln (cancer ratio)

for model 2.

Therefore, model 2 correctly classified a higher proportion of patients with MPE (98.8%) than model 1 (87.5%) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Classification of the two prediction models

| Model | Observed neoplasia | Predicted neoplasia | Percentage correct (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | |||

| 1 | No | 103 | 17 | 85.8 |

| Yes | 13 | 107 | 89.2 | |

| Overall(%) | 87.5 | |||

| 2 | No | 118 | 2 | 98.3 |

| Yes | 1 | 119 | 99.2 | |

| Overall(%) | 98.8 | |||

4. DISCUSSION

Our study confirmed that the two different predictive models have excellent discriminatory values for predicting MPE. Compared to model 1 (only clinical‐radiological data), model 2 (clinical‐radiological data, CEA and the cancer ratio) was superior to differentiate between MPE and non‐MPE. This model could provide additional evidence to support the decision of whether to perform a pleuroscopy on an exudative pleural effusion.

Pleural effusion is diagnosed as being malignant if the cytology or biopsy is positive for malignancy. The diagnostic yield of cytology and pleural biopsy is approximately 70%.2, 9 However, conventional diagnostic methods are sometimes invasive.10 Even though pleuroscopy can determine the cause of pleural effusion in patients with an accuracy of 95%, it is invasive and not available in most hospitals.11, 12 Therefore, developing a highly accurate, less invasive, accessible and early detection method is imperative for diagnosing the cause of pleural effusions.

Binary logistic regression models were applied in the present study, and to quantify how good the predictions from the model performances were, the discrimination, calibration, diagnostic accuracy, and overfitting by bootstrap resampling were examined. No overfitting was found. Model 1 included clinical‐radiological data only and was intended to be applied in hospitals that had limitations in performing biochemical tests for pleural effusion. This model was constructed with the following variables: serosanguinous appearance of pleural effusion, X‐ray/CT images suggestive of malignancy, prevalence of clinical symptoms for greater than 30 days, and absence of chest pain. This model (AUC = 0.936) correctly classified 89.2% of the MPE patients and 85.8% of the non‐MPE patients. The selected variables were consistent with the usually described clinical characteristics for MPE and non‐MPE. The variable with the greatest discriminatory capacity was the X‐ray/CT images suggestive of malignancy, as such that their presence increased by 18 times the probability of the pleural effusion being malignant (Table 3). It is consistent with Valdes L et al,13 Ferreiro et al,14 and Ferrer J et al15 Compared with non‐MPE patients, MPE patients had a more frequent serosanguinous appearance of pleural effusion.16 Luis Valdes et al15proposed a predictive MPE model that was composed of chest pain, fever and the presence of radiological images suggestive of malignancy that classified 87.2% of patients with MPE. In contrast, our model did not consider fever. The fact the studies used different methodologies may also contribute to these differences. In addition, chest pain is a common symptom in tuberculous pleural effusion, yet in MPE, it is rare. Thus, the predictive model in our study was constructed with X‐ray/CT images suggestive of malignancy, the absence of chest pain, prevalence of clinical symptoms for greater than 30 days, and serosanguinous appearance of pleural effusion.

Model 2 was composed of clinical‐radiological data (same as model 1) with the additional analytical variables of lnCEA and ln(cancer ratio). CEA was chosen because it is the most extensively studied predictor of MPE and shows a high diagnostic capacity for MPE.6, 17, 18, 19, 20 Compared to the pleural carcinoembryonic antigen (pCEA), the sensitivity and specificity of the “cancer ratio” was found to be higher in the present study. The AUC for the cancer ratio and pCEA were 0.958 and 0.927, respectively. Additionally, Akash Verma et al21 reported that the cancer ratio showed a great predictive capacity in 163 patients with exudation pleural effusion (100 with MPE and 63 with non‐MPE). When the cutoff level of the cancer ratio was greater than 20, the positive predictive value was 32.6. In addition, the negative predictive value was 0.03. Thus, the cancer ratio achieves a high sensitivity and specificity in the differential diagnosis of MPE and non‐MPE, with the cancer ratio included in model 2. Compared with model 1, model 2 provided better classification of 12 patients with MPE and another 15 with non‐MPE, showing an AUC of 0.998, which was significantly better than model 1 (P < 0.001). Therefore, the diagnostic yield of model 2 was greater for the diagnosis of MPE. The combination of the cancer ratio, clinical‐radiology, and CEA further increased the diagnostic yield of the cancer ratio in identifying MPE. In addition, the two models proposed here can be derived from routinely performed biochemical tests and clinical variables, and can accurately identify MPE without any additional tests, costs or time.

Serum LDH is a ubiquitous cellular enzyme that increases in response to tissue injury in a nonspecific manner.22 This mechanism in malignancies is well studied and the diagnostic yield for MPE has been widely researched.21, 23, 24 However, pleural ADA is deemed to be low in MPE. Consequently, we combined serum LDH and pleural ADA in the present study.

One limitation of the present study is that both predictive models were constructed based on patients that were retrospectively reviewed at a single center. The findings require validation in prospective and multicentre studies.

5. CONCLUSION

In summary, both models achieved a high diagnostic accuracy for the prediction of MPE. However, model 2, which comprises the cancer ratio, CEA, and clinical‐radiological parameters, was superior to model 1.

Pan Y, Bai W, Chen J, et al. Diagnosing malignant pleural effusion using clinical and analytical parameters. J Clin Lab Anal. 2019;33:e22689 10.1002/jcla.22689

REFERENCES

- 1. Light RW. Clinical practice. Pleural effusion. N Engl J Med. 2002;346(25):1971‐1977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Sahn SA. State of the art. The pleura. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1988;138(1):184‐234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Porcel JM, Vives M, Esquerda A, Salud A, Perez B, Rodriguez‐Panadero F. Use of a panel of tumor markers (carcinoembryonic antigen, cancer antigen 125, carbohydrate antigen 15–3, and cytokeratin 19 fragments) in pleural fluid for the differential diagnosis of benign and malignant effusions. Chest. 2004;126(6):1757‐1763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Huang WW, Tsao SM, Lai CL, Su CC, Tseng CE. Diagnostic value of Her‐2/neu, Cyfra 21–1, and carcinoembryonic antigen levels in malignant pleural effusions of lung adenocarcinoma. Pathology. 2010;42(3):224‐228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hackbarth JS, Murata K, Reilly WM, Algeciras‐Schimnich A. Performance of CEA and CA19‐9 in identifying pleural effusions caused by specific malignancies. Clin Biochem. 2010;43(13–14):1051‐1055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Yang Y, Liu YL, Shi HZ. Diagnostic accuracy of combinations of tumor markers for malignant pleural effusion: An updated meta‐analysis. Respiration. 2017;94(1):62‐69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Team R , Team RR . A language and environment for statistical computing. 2013. Computing. 2011;1:12–21. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Andersen PK. Regression modeling strategies with applications to linear models, logistic regression and survival analysis. Stat Med. 2010;22(15):2531–2532. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Maskell NA, Butland RJ. BTS guidelines for the investigation of a unilateral pleural effusion in adults. Thorax. 2003;58(Suppl 2):ii8‐ii17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Chopra A, Argula R, Schaefer C, Judson MA, Huggins T. The value of sound waves and pleural manometry in diagnosing a pleural effusion with the dual diagnosis. Thorax. 2016;71(11):1064–1065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hansen M, Faurschou P, Clementsen P. Medical thoracoscopy, results and complications in 146 patients: a retrospective study. Respir Med. 1998;92(2):228–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Rodriguez‐Panadero F, Janssen JP, Astoul P. Thoracoscopy: general overview and place in the diagnosis and management of pleural effusion. Eur Respir J. 2006;28(2):409–422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Valdes L, San‐Jose E, Ferreiro L, et al. Combining clinical and analytical parameters improves prediction of malignant pleural effusion. Lung. 2013;191(6):633–643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ferreiro L, Gude F, Toubes ME, et al. Predictive models of malignant transudative pleural effusions. J Thorac Dis. 2017;9(1):106–116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ferrer J, Roldan J, Teixidor J, Pallisa E, Gich I, Morell F. Predictors of pleural malignancy in patients with pleural effusion undergoing thoracoscopy. Chest. 2005;127(3):1017–1022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Porcel JM, Vives M Differentiating tuberculous from malignant pleural effusions: a scoring model. Med Sci Monit. 2003;9(5):CR16‐CR180. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Chen M, Xie S, Wan C, et al. Diagnostic performance of CTLA‐4, carcinoembryonic antigen and CYFRA 21–1 for malignant pleural effusion. Postgrad Med. 2017;129(6):644–648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Jing X, Wei F, Li J, et al. Diagnostic value of soluble B7–H4 and carcinoembryonic antigen in distinguishing malignant from benign pleural effusion. Clin Respir J. 2018;12(3):986–990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Zhai K, Wang W, Wang Y, Liu JY, Zhou Q, Shi HZ. Diagnostic accuracy of tumor markers for malignant pleural effusion: a derivation and validation study. J Thorac Dis. 2017;9(12):5220–5229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Yu YX, Tong ZH, Zhou XX, et al. Evaluation of the diagnosis value of carcinoembryonic antigen in malignant pleural effusion. Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2018;98(6):432–435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Verma A, Abisheganaden J, Light RW. Identifying malignant pleural effusion by a cancer ratio (serum LDH: pleural fluid ADA ratio). Lung. 2016;194(1):147–153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Rosalki S. Clinical enzymology. A case‐oriented approach. J Clin Pathol. 1988;41(1):119‐119. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Goldman RD, Kaplan NO, Hall TC. Lactic dehydrogenase in human neoplastic tissues. Cancer Res. 1964;24:389–399. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Nishio K, Jacobson KB, Jenkins VK, Upton. AC. Studies on plasma lactic dehydrogenase in mice with myeloid leukemia. I. Relation of enzyme level to course of disease. Cancer Res. 1963;23:340–343. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]