Abstract

Objective

To compare the superior‐level facet joint violations (FJV) between robot‐assisted (RA) percutaneous pedicle screw placement and conventional open fluoroscopic‐guided (FG) pedicle screw placement in a prospective cohort study.

Methods

This was a prospective cohort study without randomization. One‐hundred patients scheduled to undergo RA (n = 50) or FG (n = 50) transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion were included from February 2016 to May 2018. The grade of FJV, the distance between pedicle screws and the corresponding proximal facet joint, and intra‐pedicle accuracy of the top screw were evaluated based on postoperative CT scan. Patient demographics, perioperative outcomes, and radiation exposure were recorded and compared. Perioperative outcomes include surgical time, intraoperative blood loss, postoperative length of stay, conversion, and revision surgeries.

Results

Of the 100 screws in the RA group, 4 violated the proximal facet joint, while 26 of 100 in the FG group had FJV (P = 0.000). In the RA group, 3 and 1 screws were classified as grade 1 and 2, respectively. Of the 26 FJV screws in the FG group, 17 screws were scored as grade 1, 6 screws were grade 2, and 3 screws were grade 3. Significantly more severe FJV were noted in the FG group than in the RA group (P = 0.000). There was a statistically significant difference between RA and FG for overall violation grade (0.05 vs 0.38, P = 0.000). The average distance of pedicle screws from facet joints in the RA group (4.16 ± 2.60 mm) was larger than that in the FG group (1.92 ± 1.55 mm; P = 0.000). For intra‐pedicle accuracy, the rate of perfect screw position was greater in the RA group than in the FG group (85% vs 71%; P = 0.017). No statistically significant difference was found between the clinically acceptable screws between groups (P = 0.279). The radiation dose was higher in the FG group (30.3 ± 11.3 vs 65.3 ± 28.3 μSv; P = 0.000). The operative time in the RA group was significantly longer (184.7 ± 54.3 vs 117.8 ± 36.9 min; P = 0.000).

Conclusions

Compared to the open FG technique, minimally invasive RA spine surgery was associated with fewer proximal facet joint violations, larger facet to screw distance, and higher intra‐pedicle accuracy.

Keywords: Cohort study, Freehand technique, Proximal facet joint violation, Robotic‐assisted pedicle screw fixation

Introduction

The transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion (TLIF) is successful in treating lumbar spinal diseases1, 2, 3. Freehand placement of pedicle screws remains the most widely used method in the TLIF procedure, with significant risk of adjacent tissue damage and complications4. However, the unique anatomy of the lumbar spine poses a significant challenge for inserting pedicle screws accurately. The rate of inaccuracy of the freehand technique for thoracolumbar pedicle screw placement is nearly 10% according to a systematic review5. Even with fluoroscopic assistance, there is still high risk of screw malposition, which may compromise the stiffness of the screw–rod construct.

Facet join violation (FJV) is defined as a screw within 1 mm of the facet joint6. One concern regarding the TLIF procedure is the risk of FJV at the superior motion segment. In the past, surgeons usually focused on the accuracy of pedicle screw placement but ignored the superior‐segment FJV. The incidence of FJV ranges from 9.5% to 32.0% of screws, according to previous studies6, 7, 8, 9. Therefore, FJV by pedicle screws is not a rare adverse event in instrumented lumbar fusion surgery. Facet joints are responsible for load‐bearing during spinal movements10. Damage to the facet joint during placement of pedicle screws can contribute to increased stress at the adjacent level and possibly lead to adjacent segment disease, requiring additional treatment11, 12. FJV was also independently associated with a higher reoperation rate and diminished improvement in quality of life13.

The techniques, equipment, and practices of spinal surgery have improved over the last two decades14. The introduction of robots into TLIF surgery could minimize some potential problems of freehand manipulation found in conventional TLIF. For minimally invasive TLIF surgeries with limited exposure, the guidance of robots has shown superiority compared with conventional methods. Use of navigation‐guided robots in spinal procedures allows surgeons to visualize and navigate complex anatomic structures while applying a minimal invasive approach. There are several orthopaedic surgical robots that have been reported to be suitable for pedicle screw fixation, including the TiRobot, ROSA, SpineAssist, and Renaissance. Some studies have compared the robot‐assisted (RA) technique with the conventional technique, mainly focused on the intra‐pedicle accuracy of pedicle screws and radiation exposure15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20. While some studies have compared the presence of FJV, to the best of our knowledge, no study has mentioned a specific FJV degree of these two techniques. The TiRobot system is the first orthopaedic surgical robot researched and developed in China, with completely independent intellectual property. It can be used in spinal surgery and traumatic orthopaedic surgery21, 22, 23, 24. This robotic technique is a practical clinical application of computer‐assisted minimally invasive spine surgery (CAMISS), which achieves better clinical outcomes with the advantages of less invasion, less injury, and better recovery, and has also became the gold standard for spine surgery25. During the current study, the TiRobot system was used to assist pedicle screw placement in the TLIF procedure.

The aim of this prospective cohort study was to compare RA percutaneous pedicle screw placement with conventional open fluoroscopy‐guided (FG) pedicle screw placement. Three major outcomes were evaluated: (i) the incidence and degree of superior‐level FJV; (ii) the distance between each pedicle screw and corresponding proximal facet joint; and (iii) the intra‐pedicle accuracy of proximal screws according to the Gertzbein and Robbins scale.

Materials and Methods

Patient Selection

Patients were selected using the following inclusion criteria: (i) lumbar degenerative disease (L1–S1) resulting in radiculopathy; (ii) ineffective results with conservative treatment for no less than 6 months. Exclusion criteria were as follows: (i) presence of scoliosis greater than 30°; (ii) previously diagnosed osteomalacia or severe osteoporosis; (iii) history of spinal tumors or tuberculosis; and (iv) spinal infection.

Study Design

This prospective non‐randomized cohort study recruited patients scheduled to undergo TLIF between February 2016 and May 2018. The hospital's Institutional Review Board approved this study. Informed consent was provided by all participants.

Sample size estimation was based on the difference in the incidence of FJV. To detect a 20% difference between groups with alpha 0.05 and beta 0.2, 47 patients in each group were required. To avoid possible dropout or conversion, we prospectively recruited 50 patients in each group.

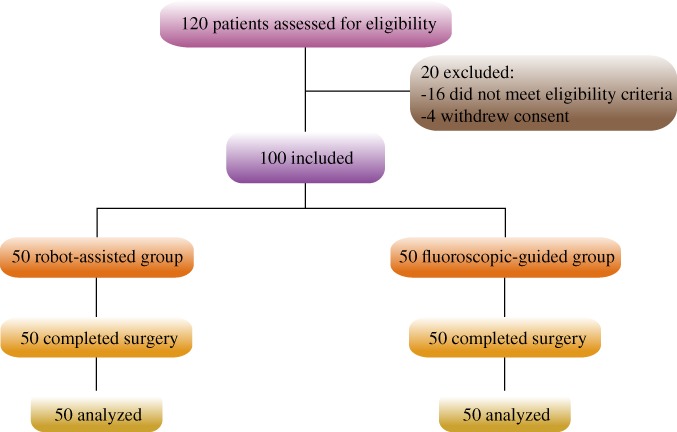

Robot‐assisted (RA) or fluoroscopy‐guided (FG) treatment was chosen by patients, after the details of these two methods were explained by the surgeon. All TLIF procedures were performed by two surgeons, who were blinded to the purpose of this study. Every surgeon completed 25 surgeries in each group. The RA group comprised patients (n = 50) treated under robotic minimal invasive surgery. The FG group comprised patients (n = 50) treated using conventional open fluoroscopy guided freehand procedure. (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Flowchart of enrolled patients, including enrolment, assigned interventions, and analysis of the study participants.

Surgical Technique

Robot‐assisted TLIF procedures were performed using the TiRobot system (TINAVI Medical Technologies, Beijing, China)26. The patient tracker was percutaneously anchored at the spinal process. Intraoperative 3D fluoroscopic images were acquired using the C‐arm scanner (ARCADIS Orbic 3D C‐arm, Siemens Medical Solutions, Erlangen, Germany) and then transferred to the robotic workstation. After planning of pedicle screws through the TiRobot workstation by surgeons, the robotic arm was instructed to move to the chosen trajectory. Then, guiding pins and pedicle screws were successively inserted through the cannula at the distal end of the robotic arm (Fig. 2). Decompression and placement of interbody devices were performed subsequently.

Figure 2.

One procedure of the robot‐assisted surgery. Guiding pins were inserted through the cannula at the distal end of the robotic arm.

Conventional open FG pedicle screw placement was performed through a midline incision. Pedicle screws were inserted by freehand under fluoroscopic guidance and verification3. Decompression and interbody fusion procedures were performed subsequently.

Outcome Measures

Facet Join Violation Incidence and Grade

Postoperative CT scans were performed to evaluate the pedicle screw position. All screws were evaluated by axial images, including the coronal and sagittal reconstructions. Two cranial screws of each patient were evaluated and compared. The accuracy of pedicle screw placement was independently reviewed by one spine surgeon and one radiologist, who were blind to the allocation and purpose of this study. In case of disagreement in categorical grading, a third senior surgeon was involved for adjudication.

The grade of FJV was evaluated according to the modified method of Babu et al.6, 7: Grade 0, no violation; Grade 1, pedicle screw and/or head within 1 mm of the abutting facet joint, without clear joint violation; Grade 2, pedicle screw within the facet joint; and Grade 3, pedicle screw traveling within the articular surface of the facet. (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

CT scans demonstrating the grade of facet joint violation: (A) Grade 0, no violation; (B) Grade 1, pedicle screw and/or head within 1 mm of the abutting facet joint, without clear joint violation; (C) Grade 2, pedicle screw within the facet joint; and (D) Grade 3, pedicle screw traveling within the articular surface of the facet.

The incidence and mean grade of FJV were compared. The mean grade of FJV was calculated by accumulation of each screw grade. The measurement of the distance between each pedicle screw and corresponding proximal facet joint was conducted according to the method previously reported by Kim et al.17. The distance was determined as the mean of two measurements.

Intra‐Pedicle Accuracy (Pedicle Screw Position)

For intra‐pedicle accuracy, pedicle screws were assessed according to the Gertzbein and Robbins scale27. Grade A: excellent screw position, no cortex perforation; Grade B: pedicle cortical breach <2 mm; Grade C: 2 mm ≤ pedicle cortical breach <4 mm; Grade D: 4 mm ≤ pedicle cortical breach <6 mm; Grade E: pedicle cortical breach ≥6 mm.

Perioperative Outcomes

Surgical time (from skin to skin), intraoperative blood loss, postoperative length of stay, conversion and revision surgeries were noted and evaluated. Patient characteristics such as age, gender, and BMI were also recorded.

Radiation Exposure

The cumulative radiation time (seconds) of each patient was recorded from the direct output of the C‐arm. Digital dosimeters were worn on the outside of the surgeon's trunk protector to assess the radiation exposure to medical staff.

Statistical Analysis

The χ2‐test and Fisher exact test (gender, FJV incidence, conversion or revision, and rate of perfect and acceptable screw position) or Student t‐test (age, body mass index, operative time, blood loss, radiation exposure, length of stay, mean grade, and distance between screw and facet joint) or the Mann–Whitney U‐test (FJV grade) were used to evaluate between‐group differences. Statistical analysis was conducted using SPSS (version 24.0; SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA). The level of statistical significance was set as P‐value <0.05.

Results

Patient Demographics

There was no statistically significant difference in age, gender, and body mass index between groups. The distribution of the cranial screw level was similar between the groups (P = 0.640). (Table 1).

Table 1.

Patient demographics and perioperative factors between groups

| Variable | Robot‐assisted group | Fluoroscopic‐guided group | P‐value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | 50 | 50 | ‐ |

| Age (years) | 54.6 ± 11.1 | 55.6 ± 12.8 | 0.683 |

| Female, n (%) | 33 (66%) | 29 (58%) | 0.410 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 25.6 ± 3.9 | 25.3 ± 3.1 | 0.706 |

| Cranial screws level | 0.640 | ||

| L2 | 1 | 3 | ‐ |

| L3 | 3 | 5 | ‐ |

| L4 | 31 | 28 | ‐ |

| L5 | 15 | 14 | ‐ |

| Operative time (min) | 184.7 ± 54.3 | 117.8 ± 36.9 | 0.000 |

| Intraoperative blood loss (mL) | 171.6 ± 123.1 | 362.0 ± 356.8 | 0.001 |

| Postoperative length of stay (days) | 5.1 ± 1.0 | 5.6 ± 2.6 | 0.157 |

| Conversion or revision | 0 | 1 | 1.000 |

| Radiation time (s) | 85.3 ± 27.8 | 75.4 ± 33.0 | 0.109 |

| Radiation dose (μSv) | 30.3 ± 11.3 | 65.3 ± 28.3 | 0.000 |

Facet Join Violation Incidence and Grade

Cranial FJV occurred in 4 top‐level screws in the RA group, significantly less (22.0%) than 26 top‐level screws implanted in the FG group (P = 0.000). In the RA group, 3 and 1 screws were classified as grade 1 and 2, respectively. Of the 26 FJV screws in the FG group, 17 screws were scored as grade 1, 6 screws were grade 2, and 3 screws were grade 3. Significantly more severe FJV were noted in the FG group than in the RA group (P = 0.000). There was a statistically significant difference between RA and FG for overall violation grade (0.05 vs 0.38, P = 0.000). The mean facet to screw distance of the RA group was significantly larger (2.17 times) than that of the FG group (4.16 ± 2.60 mm vs 1.92 ± 1.55 mm, P = 0.000) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Superior‐level facet joint violation of robot‐assisted and fluoroscopic‐guided pedicle screw placement

| Variable | Robot‐assisted group | Fluoroscopic‐guided group | P‐value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cranial screws | 100 | 100 | |

| FJV incidence | 4 | 26 | 0.000 |

| FJV grade | 0.000 | ||

| Grade 0 | 96 | 74 | ‐ |

| Grade 1 | 3 | 17 | ‐ |

| Grade 2 | 1 | 6 | ‐ |

| Grade 3 | 0 | 3 | ‐ |

| Mean Grade | 0.05 | 0.38 | 0.000 |

| Distance between pedicle screw and facet joint (mm) | 4.16 ± 2.60 | 1.92 ± 1.55 | 0.000 |

FJV, facet joint violations

Intra‐Pedicle Accuracy

Of the 100 cranial screws placed in the RA group, 85 were grade A, and 13 and 2 screws were classified as grade B and C, respectively. Of the 100 superior‐level screws in the FG group, 71 screws were grade A, 23 screws were grade B, 4 screws were grade C, and 2 screws were grade E. The rate of perfect screw position (grade A) was greater (14.0%) in the RA group than in the FG group (85.0% vs 71.0%; P = 0.017). A total of 98 screws in the RA group and 94 screws in FG group were clinically acceptable screws (group A and B). No statistically significant difference was found between the clinically acceptable screws between groups (P = 0.279) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Intra‐pedicle accuracy of cranial pedicle screws

| Screw grade | Robot‐assisted group | Fluoroscopic‐guided group | P‐value |

|---|---|---|---|

| A | 85 | 71 | 0.017 |

| B | 13 | 23 | ‐ |

| A+B | 98 | 94 | 0.279 |

| C | 2 | 4 | ‐ |

| D | 0 | 0 | ‐ |

| E | 0 | 2 | ‐ |

Perioperative Outcomes

The operative time in the RA group was significantly longer (1.57 times) (184.7 ± 54.3 vs 117.8 ± 36.9 min; P = 0.000). The blood loss of the FG group was significantly higher (2.11 times) than that of the RA group (171.6 ± 123.1 mL vs 362.0 ± 356.8 mL, P = 0.001). The postoperative length of stay was shorter in the RA (5.1 ± 1.0 days) than in the FG group (5.6 ± 2.6 days), but the difference was not significant (P = 0.157). No RA screws required intraoperative conversion to the FG or revision. One revision was required in the FG group for persistent postoperative radicular pain due to misplaced pedicle screws (Grade E). (Table 1).

Radiation Exposure

The radiation time was longer in the RA (85.3 ± 27.8 s) than in the FG group (75.4 ± 33.0 s), but this difference was not statistically significant (P = 0.109). The radiation dose was significantly higher (2.16 times) in the FG group (30.3 ± 11.3 vs 65.3 ± 28.3 μSv; P = 0.000). (Table 1).

Discussion

In the current study, we mainly examined the superior‐level FJV of RA and FG pedicle screw implantation in TLIF procedure, with a prospective design. The main finding of this study is that the minimally invasive RA technique was better than the open FG technique in terms of proximal FJV grade and intra‐pedicle accuracy. We also demonstrated that the distance of pedicle screws from the proximal facet joints in the RA group was significantly greater than that in the FG group. It is the first report to compare the specific FJV degree between the RA and FG techniques.

The primary benefit of the RA application is to control the implant placement at a precise, pre‐planned, ideal screw trajectory using a minimally invasive approach, helping to prevent screws from cortical breach of the pedicle and proximal FJV. The current study found that the incidence and grade of proximal FJV for percutaneous robotic pedicle screw insertion was lower than the rate for fluoroscopy‐assisted procedures. This difference can be explained by the mechanism of intraoperative robotic guidance. Fluoroscopy‐based freehand screw insertion involves surgeons' hand–eye coordination, while the robotic system mechanically guides the surgeons to the pre‐planned trajectory. In addition, the soft tissue resistance of percutaneous guide pin insertion via robotic arm was less than that of the freehand technique. In this study, FJV was more common at the L5 level for both techniques. A possible explanation is that the lateral iliac crest interfered with the medial–lateral trajectory during placement of the pedicle screw at L58.

The incidence of FJV in association with the RA technique has been reported in previous studies. Hyun et al.16 conducted a prospective randomized study to compare the RA technique with the FG technique in a minimally invasive spine surgery. No proximal FJV occurred in the RA group, and the average distance from the proximal facets was larger in the RA group than in the FG group. Kim et al.17 also assessed the proximal FJV between these two groups. They found that the proximal FJV was significantly different between the robotic and freehand groups, with less FJV and larger facet to screw distance in the robotic group. In a finite element analysis, Kim et al.28 showed the biomechanical advantages of RA pedicle screw insertion in terms of alleviation of stress concentration at proximal adjacent segments after fusion surgery, compared with pedicle screw insertion using the freehand technique. Considering our results of less incidence of FJV and larger screw to facet distance of the robotic procedure, the RA spine surgery might have an advantage in reducing the stress at the adjacent segment. The rate of proximal FJV in our RA group was higher than in the abovementioned articles. This finding was due to the surgeons being concerned mainly with avoiding cortical violation, and not enough attention being paid to the facet joints. As FJV may be a factor in the development of adjacent segment disease, there is growing focus on the impact of the top screw on adjacent segment disease6, 11, 29, 30. We considered that avoidance of FJV is a higher requirement than achieving intra‐pedicle accuracy.

According to the report of Babu et al.6, percutaneous pedicle screw insertion is associated with a higher incidence of higher grade facet joint violation compared to the traditional open approach. In contrast, we found that percutaneous RA pedicle screw placement had fewer proximal FJV and lower FJV grade compared to the open freehand technique. Our higher accuracy verified the advantage of medical robots, which could promote the development of minimal invasive surgery.

In our study, the RA group had significantly higher intra‐pedicle accuracy. The higher accuracy achieved in the RA cohort was consistent with some previous studies. Lieberman et al.31 demonstrated that the RA pedicle screw placement had fewer screw placement deviations and fewer cortical breaches than the freehand group. Kantelhardt et al.32 showed that the use of robotic guidance significantly increased the accuracy of screw positioning. Hyun et al.16 also suggested a higher precision rate when using the robotic guidance. Roser et al.15 demonstrated that the use of robotics in spinal surgery greatly increased accuracy compared with conventional FG procedures. The study by Pechlivanis et al.33 demonstrated a rate of 98.5% clinically acceptable screws in their series of 133 percutaneous robotic‐guided screws.

The total radiation time in the FG group was lower than in the RA group. This could be attributed to additional 3D scans of the robotic system for intraoperative planning. However, this extended radiation time would not increase the radiation dose to the medical staff because they left the operating room during the 3D scans. Thus, the radiation dose in the RA group was lower than in the FG group. Some other studies also reported a reduction of radiation exposure for the RA spine surgery16, 31, 34.

The longer surgical duration of the RA group could be attributed to more intraoperative preparation work needed for the robot system. Longer surgical time has also been noted in other robot systems for spine surgery17, 19, 35. In the FG group, the intraoperative blood loss was significantly higher than in the RA group. This was because the percutaneous minimal invasive technique used in the RA group, while patients in the FG group underwent an open dissection.

No revision occurred in the RA group, but one revision was needed in the FG group. Computer assistance in the form of robotic guidance or navigation has the potential to reduce the incidence of postoperative revisions of pedicle screws, according to a meta‐analysis36. After 2‐year follow up, Park et al.37 found that there was no statistic difference for revision between RA and FG techniques.

This study had some inherent limitations. These results were radiological and perioperative clinical outcomes from a cohort study. To assess the difference in outcomes between groups, randomized controlled trials and long‐term follow up were warranted. Furthermore, the minimally invasive RA procedure and the open FG procedure were compared in this study. A study to investigate the FJV of RA and FG minimally invasive TLIF is needed in the future. Finally, the number of patients included in this study was relatively small. Further studies involving more centers and participants are needed.

Conclusions

Minimally invasive RA pedicle screw placement was associated with fewer proximal FJV, lower FJV grade, larger distance of pedicle screws from the proximal facet joints, and higher intra‐pedicle accuracy, compared to the conventional open fluoroscopic‐guided technique. RA pedicle screw insertion in a minimally invasive spinal surgery can ensure accuracy and safety.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the Beijing Natural Science Foundation of China (Z170001 and 7174311) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (U1713221).

References

- 1. Rosenberg WS, Mummaneni PV. Transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion: technique, complications, and early results. Neurosurgery, 2001, 48: 569–574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Schwender JD, Holly LT, Rouben DP, Foley KT. Minimally invasive transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion (TLIF): technical feasibility and initial results. J Spinal Disord Tech, 2005, 18: S1–S6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ge DH, Stekas ND, Varlotta CG, et al Comparative analysis of two transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion techniques: open TLIF versus Wiltse MIS TLIF. Spine (Phila Pa 1976)., 2019, 44: E555–E560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Gautschi OP, Schatlo B, Schaller K, Tessitore E. Clinically relevant complications related to pedicle screw placement in thoracolumbar surgery and their management: a literature review of 35,630 pedicle screws. Neurosurg Focus, 2011, 31: E8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Perdomo‐Pantoja A, Ishida W, Zygourakis C, et al Accuracy of current techniques for placement of pedicle screws in the spine: a comprehensive systematic review and meta‐analysis of 51,161 screws. World Neurosurg, 2019, 126: 664–678. 10.1016/j.wneu.2019.02.217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Babu R, Park JG, Mehta AI, et al Comparison of superior‐level facet joint violations during open and percutaneous pedicle screw placement. Neurosurgery, 2012, 71: 962–970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Tian W, Xu Y, Liu B, et al Lumbar spine superior‐level facet joint violations: percutaneous versus open pedicle screw insertion using intraoperative 3‐dimensional computer‐assisted navigation. Chin Med J (Engl), 2014, 127: 3852–3856. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Park Y, Ha JW, Lee YT, Sung NY. Cranial facet joint violations by percutaneously placed pedicle screws adjacent to a minimally invasive lumbar spinal fusion. Spine J, 2011, 11: 295–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Moshirfar A, Jenis LG, Spector LR, et al Computed tomography evaluation of superior‐segment facet‐joint violation after pedicle instrumentation of the lumbar spine with a midline surgical approach. Spine (Phila Pa 1976), 2006, 31: 2624–2629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lorenz M, Patwardhan A, Vanderby R Jr. Load‐bearing characteristics of lumbar facets in normal and surgically altered spinal segments. Spine (Phila Pa 1976), 1983, 8: 122–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Park P, Garton HJ, Gala VC, Hoff JT, McGillicuddy JE. Adjacent segment disease after lumbar or lumbosacral fusion: review of the literature. Spine (Phila Pa 1976), 2004, 29: 1938–1944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kim HJ, Chun HJ, Kang KT, et al The biomechanical effect of pedicle screws' insertion angle and position on the superior adjacent segment in 1 segment lumbar fusion. Spine (Phila Pa 1976), 2012, 37: 1637–1644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Levin JM, Alentado VJ, Healy AT, Steinmetz MP, Benzel EC, Mroz TE. Superior segment facet joint violation during instrumented lumbar fusion is associated with higher reoperation rates and diminished improvement in quality of life. Clin Spine Surg., 2018, 31: E36–E41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Fehlings MG, Ahuja CS, Mroz T, Hsu W, Harrop J. Future advances in spine surgery: the AOSpine North America perspective. Neurosurgery, 2017, 80: S1–S8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Roser F, Tatagiba M, Maier G. Spinal robotics: current applications and future perspectives. Neurosurgery, 2013, 72: 12–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hyun SJ, Kim KJ, Jahng TA, Kim HJ. Minimally invasive robotic versus open fluoroscopic‐guided spinal instrumented fusions: a randomized controlled trial. Spine (Phila Pa 1976), 2017, 42: 353–358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kim HJ, Jung WI, Chang BS, Lee CK, Kang KT, Yeom JS. A prospective, randomized, controlled trial of robot‐assisted vs freehand pedicle screw fixation in spine surgery. Int J Med Robot, 2017, 13: e1779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Laudato PA, Pierzchala K, Schizas C. Pedicle screw insertion accuracy using O‐arm, robotic guidance, or freehand technique: a comparative study. Spine (Phila Pa 1976), 2018, 43: E373–E378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lonjon N, Chan‐Seng E, Costalat V, Bonnafoux B, Vassal M, Boetto J. Robot‐assisted spine surgery: feasibility study through a prospective case‐matched analysis. Eur Spine J, 2016, 25: 947–955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Le X, Tian W, Shi Z, et al Robot‐assisted versus fluoroscopy‐assisted cortical bone trajectory screw instrumentation in lumbar spinal surgery: a matched‐cohort comparison. World Neurosurg, 2018, 120: e745–e751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Tian W. Robot‐assisted posterior C1‐2 Transarticular screw fixation for atlantoaxial instability: a case report. Spine (Phila Pa 1976)., 2016, 41: B2–B5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Han X, Tian W, Liu Y, et al Safety and accuracy of robot‐assisted versus fluoroscopy‐assisted pedicle screw insertion in thoracolumbar spinal surgery: a prospective randomized controlled trial. J Neurosurg Spine, 2019, 30: 615–622. 10.3171/2018.10.SPINE18487 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Wu JY, Yuan Q, Liu YJ, Sun YQ, Zhang Y, Tian W. Robot‐assisted percutaneous Transfacet screw fixation supplementing oblique lateral interbody fusion procedure: accuracy and safety evaluation of this novel minimally invasive technique. Orthop Surg, 2019, 11: 25–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Zhang Q, Han XG, Xu YF, et al Robot‐assisted versus fluoroscopy‐guided pedicle screw placement in transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion for lumbar degenerative disease. World Neurosurg, 2019, 125: e429–e434. 10.1016/j.wneu.2019.01.097 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Tian W, Liu Y, Fan M, Zhao J, Jin P, Zeng C. CAMISS concept and its clinical application. Adv Exp Med Biol, 2018, 1093: 31–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Tian W, Liu YJ, Liu B, et al Guideline for thoracolumbar pedicle screw placement assisted by Orthopaedic surgical robot. Orthop Surg, 2019, 11: 153–159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Gertzbein SD, Robbins SE. Accuracy of pedicular screw placement in vivo. Spine (Phila Pa 1976), 1990, 15: 11–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kim HJ, Kang KT, Park SC, et al Biomechanical advantages of robot‐assisted pedicle screw fixation in posterior lumbar interbody fusion compared with freehand technique in a prospective randomized controlled trial‐perspective for patient‐specific finite element analysis. Spine J, 2017, 17: 671–680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Knox JB, Dai JM 3rd, Orchowski JR. Superior segment facet joint violation and cortical violation after minimally invasive pedicle screw placement. Spine J, 2011, 11: 213–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Cheh G, Bridwell KH, Lenke LG, et al Adjacent segment disease following lumbar/thoracolumbar fusion with pedicle screw instrumentation: a minimum 5‐year follow‐up. Spine (Phila Pa 1976), 2007, 32: 2253–2257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Lieberman IH, Hardenbrook MA, Wang JC, Guyer RD. Assessment of pedicle screw placement accuracy, procedure time, and radiation exposure using a miniature robotic guidance system. J Spinal Disord Tech, 2012, 25: 241–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kantelhardt SR, Martinez R, Baerwinkel S, Burger R, Giese A, Rohde V. Perioperative course and accuracy of screw positioning in conventional, open robotic‐guided and percutaneous robotic‐guided, pedicle screw placement. Eur Spine J, 2011, 20: 860–868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Pechlivanis I, Kiriyanthan G, Engelhardt M, et al Percutaneous placement of pedicle screws in the lumbar spine using a bone mounted miniature robotic system: first experiences and accuracy of screw placement. Spine (Phila Pa 1976), 2009, 34: 392–398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Alaid A, von Eckardstein K, Smoll NR, et al Robot guidance for percutaneous minimally invasive placement of pedicle screws for pyogenic spondylodiscitis is associated with lower rates of wound breakdown compared to conventional fluoroscopy‐guided instrumentation. Neurosurg Rev, 2018, 41: 489–496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Yu L, Chen X, Margalit A, Peng H, Qiu G, Qian W. Robot‐assisted vs freehand pedicle screw fixation in spine surgery ‐ a systematic review and a meta‐analysis of comparative studies. Int J Med Robot, 2018, 14: e1892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Staartjes VE, Klukowska AM, Schröder ML. Pedicle screw revision in robot‐guided, navigated, and freehand thoracolumbar instrumentation: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. World Neurosurg, 2018, 116: 433–443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Park SM, Kim HJ, Lee SY, Chang BS, Lee CK, Yeom JS. Radiographic and clinical outcomes of robot‐assisted posterior pedicle screw fixation: two‐year results from a randomized controlled trial. Yonsei Med J, 2018, 59: 438–444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]