Abstract

Objective

To identify factors that explain the observed effects of internal auditing on improving patient safety.

Design setting and participants

A process evaluation study within eight departments of a university medical centre in the Netherlands.

Intervention(s)

Internal auditing and feedback for improving patient safety in hospital care.

Main outcome measure(s)

Experiences with patient safety auditing, percentage implemented improvement actions tailored to the audit results and perceived factors that hindered or facilitated the implementation of improvement actions.

Results

The respondents had positive audit experiences, with the exception of the amount of preparatory work by departments. Fifteen months after the audit visit, 21% of the intended improvement actions based on the audit results were completely implemented. Factors that hindered implementation were short implementation time: 9 months (range 5–11 months) instead of the 15 months’ planned implementation time; time-consuming and labour-intensive implementation of improvement actions; and limited organizational support for quality improvement (e.g. insufficient staff capacity and time, no available quality improvement data and information and communication technological (ICT) support).

Conclusions

A well-constructed analysis and feedback of patient safety problems is insufficient to reduce the occurrence of poor patient safety outcomes. Without focus and support in the implementation of audit-based improvement actions, quality improvement by patient safety auditing will remain limited.

Keywords: audit, process evaluation study, patient safety, hospitals

Introduction

Healthcare providers are faced with the challenge of improving patient safety by detecting and preventing the occurrence of adverse events (AEs) [1, 2]. There is a growing interest in effective and sustainable interventions for reducing AEs [3, 4]. Audit and feedback is a widely used intervention for improving quality of care in numerous settings; however, the effectiveness is variable [5–7]. After a serious event on hospital level, we implemented an internal audit system to continuously improve patient safety in hospital care [8]. Central to this audit system is the use of a peer-to-peer evaluation approach to engage healthcare providers in the plan-do-check-act (PDCA) quality-improvement cycle [8]. Audits can be seen as the ‘check’ stage of the PDCA quality improvement cycle: auditors check whether quality standards have been established (‘plan’) and applied in practice (‘do’). Based on the audit results improvement actions are implemented (‘act’) by healthcare providers and management to improve patient safety [8]. Despite this approach, we observed in a previous effect evaluation study no statistically significant effect on the primary outcome, AEs and on team climate and patient safety culture [9]. Only patients’ experiences regarding their safety, observed medication safety and information security increased [9]. We incorporated a process evaluation in our effect evaluation study to understand the effects observed [10]. In this process evaluation, we evaluated whether the internal audit, including the implementation of improvement actions and revisit 15 months after the audit visit, had been executed as planned and whether the audit results triggered departments to improve patient safety. If the internal audit in its ultimate form differed considerably from the original plan, this could lead to ‘implementation error’, meaning incorrect implementation or insufficient execution of the intervention (in this case internal auditing) can lead to incorrect conclusions about the effectiveness of the intervention [10]. The effectiveness of patient safety auditing also depends on the context in which patient safety auditing is performed [7]. Therefore, we identified internal and external factors that might influence the effectiveness of patient safety auditing. The main research question of our process evaluation was: ‘Which combination of factors explains the degree of patient safety improvement by internal auditing in hospital care?’

Based on the results of our process evaluation, we provide recommendations on how organizations can support staff to improve the audit process. This process evaluation is the second part of a mixed-method evaluation study of patient safety auditing. The results of the effect evaluation are described in part 1 of this study [9].

Methods

Study design and setting

We used the process evaluation framework described by Hulscher et al. [10] to describe the actual performance of the patient safety auditing activities and to gain insight into the experiences with patient safety auditing of those who participated in the audit (auditees) and the factors that hinder or facilitate effective patient safety auditing in detail. We formulated four research questions: (1) Were the internal audits (including revisit) executed as planned? (2) What are the auditees’ experiences with internal audits? (3) Were the improvement actions implemented as planned and what are the results regarding patient safety? and (4) What are the barriers and facilitators for the implementation of the improvement actions?

The study was performed between 2011 and 2014 on eight clinical departments of a 953-bed university hospital [8]. We used the Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ) [11] guidelines and the Standards for QUality Improvement Reporting Excellence (SQUIRE) [12] for reporting our study.

Context of patient safety auditing

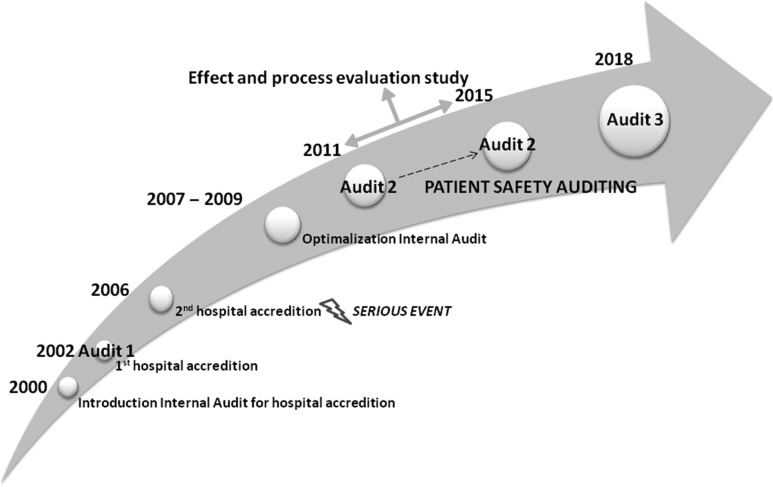

Patient safety auditing in a Dutch hospital was introduced after a serious event in 2006 that occurred due to inadequate clinical governance, lack of leadership, poor collaboration between hospital department medical staff, a blame culture and the lack of use of patient outcomes for quality improvement [13, 14]. Based on these findings, the internal audit system was optimized from 2007 to 2009 (Fig. 1). In this audit system, quality control is central and patient outcomes are the basis for quality improvements instead of controlling the presence of preconditions for good patient care as in previous audits [13]. Team climate measurements and appraisal and assessments by internal and external collaborating partners became a standard part of the internal audits. Healthcare providers were trained as auditors, and an independent board for Quality Assurance and Safety was installed. Since 2011, hospital departments, which deliver patient care, undergo an upgraded internal audit according to a fixed audit scheme of 21 months (Appendix 1) [8, 9]. The department heads write an improvement plan tailored to the audit results by using a standard improvement plan (Appendix 2). This standard should facilitate the implementation of the intended improvement actions and monitoring of progress by the department heads.

Figure 1.

Timeline of development of patient safety auditing in hospital care.

Measurements and data collection

We used a mixed-method approach for this process evaluation: (1) survey, (2) semi-structured interviews and (3) quantitative and qualitative content analysis of audit documents (Table 1).

Table 1.

Research questions, measurements and data source

| Focus | Research questions | Methods | Timing | Data source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Execution of internal audit | 1) Were the internal audits (including revisit) executed as planned? | Quantitative content analysis of documents | >1 month after revisit |

|

| 2) What are the experiences of auditees with internal audits? |

|

|

|

|

| Implementation of improvement actions |

|

|

|

|

| 4) What are the barriers and facilitators for the implementation of improvement actions? |

|

|

|

(1) Survey

We developed a web-based questionnaire to evaluate the auditees’ experiences (Appendix 3). The questions covered the elements of the audit process [8, 9] and its perceived strengths and limitations. The face validity of the questionnaire was examined by expert review (n = 10) and one plenary expert discussion meeting, and was tested in two departments. This led to refining of the formulations and the removal of three items from the questionnaire. The auditees received the questionnaire online within 2 weeks after the internal audit. Non-respondents received one reminder to reduce non-response bias.

(2) Interviews

To cover the topics experiences in-depth with (strengths and limitations of) patient safety auditing, implementation of improvement actions and the barriers and facilitators of the implementation, an experienced interviewer conducted 24 semi-structured face-to-face interviews (60 min each) from March 2013 to October 2014 using an interview topic guide (Appendix 4). The interviews took place at the workplace within 1 month after the revisit. Purposive sampling was used to select a varied group of healthcare professionals to ensure diversity regarding involvement in the internal audits and job type [15]. The interviewees were informed about the study and its aim by e-mail and provided verbal informed consent at the beginning of the interview.

(3) Quantitative and qualitative content analysis of audit documents

The audit results were classified by an independent fixed team of four analysts into four quality domains [16]: management structure, preconditions, care processes and outcomes. The degree of implementation of the audit-based improvement actions was independently assessed by the two auditors who revisited the department. They used a 4-point rating scale [16]: 1 = not implemented, 2 = partly implemented, 3 = nearly implemented, 4 = completely implemented (5 = not assessed), and tabulated the final scores in the revisit reports. Disagreements on the classification and scores were discussed until consensus was reached.

Data analysis

The questionnaire data was analysed descriptively using the statistical software IBM SPSS V.22. The percentages of positive and negative experiences were calculated for each question by combining two positively phrased ratings, i.e. ‘agreed and strongly agreed’, and two negatively phrased ratings, i.e. ‘disagree and strongly disagree’, respectively. A positive response >80% and a negative response >10% were considered a strength and limitation, respectively, of patient safety auditing. This was a data driven decision meaningful for practice.

The barriers and facilitators from the interviews (n = 24) and the revisit reports (n = 8) were qualitatively analysed by thematic analysis [15, 17] and directed content analysis [18], respectively. The interviews were audio-taped and transcribed verbatim according to a standardized format. Two researchers (M.H.-S. and E.P.) analysed the transcripts (n = 24) independently using the coding framework based on the integrated checklist of determinants of practice (TICD) of Flottrop [19] (see Appendix 5 for the coding tree). The interview data were discussed, replaced or recoded until consensus was reached. One researcher (M.H.-S.) systematically read the revisit reports, coded the barriers and facilitators using the interview coding framework, recoded in consultation with a second researcher (P.Jv.G.) and organized the final codes into a hierarchical structure if possible. M.H.-S tabulated all perceived barriers and facilitators and described the prominent sub-categories with illustrative quotes. M.H.-S., M.Z., P.Jv.G., H.W. and G.P.W. studied and discussed the prominent sub-categories in two team meetings. Atlas.ti.7 was used for coding, annotating and interpreting the results in the primary data material of the interviews and revisit reports.

IBM SPSS V.22 was used to calculate the median time (in months) between audit visit and audit preparation, audit report handover, completion of the implementation plan, actual implementation of improvement actions and revisit by the audit team, respectively, and the classification of the audit results and the implementation rating scores. The 4-point implementation rating scale was therefore split into two scores: ‘completely implemented’ (4 points) and ‘not implemented’ (1–3 points). Improvement actions that were not assessed (n = 2) were excluded from the analysis.

Results

Execution of the internal audit

The internal audits (n = 8) were performed by 34 auditors in total: 27 physicians, three nurses and four allied healthcare workers. In total, 402 auditees were interviewed at the audit visit: 37.6% were physicians, 27.6% were nurses, 13.7% were managers, 8.5% were healthcare researchers, 5.5% were secretaries, 4.5% were allied healthcare workers and 2.7% were outpatient clinic employees. The median times were 5 months (range, 4–6 months) for audit preparation, 3 months (range, 2–3 months) for audit report handover to the department head, 3 months (range, 2–7.5 months) for completing the improvement plan, 9 months (range, 5–11 months) for starting of the implementation of the improvement plan and 15 months (range, 15–18 months) for performing the revisit.

A pool of 10 auditors consisting of seven physicians, two nurses and one allied healthcare worker revisited the eight departments. They interviewed a total of 88 auditees, who were purposive selected on their involvement in the implementation of the audit-based improvement actions: 38.6% were physicians, 17.0% were nurses, 33.0% were managers, 1.1% were secretaries, 4.5% were allied healthcare workers, 1.1% were outpatient clinic employees and 4.5% were others.

Auditees’ experiences with internal audits

Of the 402 invited auditees, 213 (53.0%) filled in the questionnaire. Respondents were mainly physicians (32.4%), nurses (23.5%) and managers (23.9%). The other respondents were allied healthcare workers (2.8%), administrative staff (5.2%), researchers (3.3%), quality officers (6.6%) and unknown (2.3%). All heads of the departments involved (n = 16) responded. The distribution of job types of the respondents (e.g. physicians, nurses) corresponded to the distribution in the total group of auditees.

Overall, 81.7% of the respondents had positive experiences with the internal audit; 84.1% indicated that the purpose of the audit was clear to them, 80.3% said that the internal audit was well-tailored and 80.7% considered the performance of the internal auditors professional (Appendix 3). Of the department heads, 86.4% indicated that the internal audit added value for improving quality of care. However, 36.4% felt that the amount of preparatory work required of the department was disproportional to the benefits, and 13.6% disagreed that the audit preparation was efficient. An overview of the results for each item is shown in Appendix 3.

Implementation of the intended improvement actions

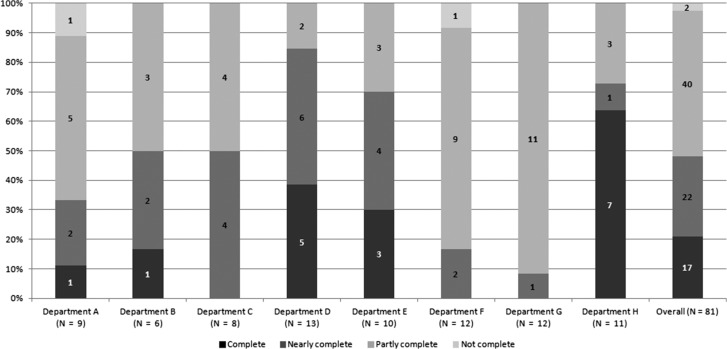

In total, the eight departments formulated 81 improvement actions varying from 6 to 13 actions per department. Fifteen months after the internal audit, 21% (n = 17) of the 81 actions were implemented; 79% (n = 64) were partly implemented or not implemented (Fig. 2). The completed improvement actions were mainly related to medical devices and sterile medical aids management, documenting care processes in protocols and the use of existing indicators for monitoring the quality of care processes. The partly implemented or not implemented actions were related to the reorganization of multidisciplinary care processes (e.g. physician visit structure, outdoor clinic), improving inter-departmental collaboration, implementation of the national patient safety programme for Dutch hospitals [20], medical and nursing staff recruitment and evaluation of the departmental quality policy.

Figure 2.

The number of improvement actions and percentage degree of implementation per department and overall 15 months after the audit visit.

Perceived facilitators and barriers for implementing quality improvement actions

In total, 24 auditees were interviewed (interviewees), i.e. three per department (n = 8): six medical heads of departments, four department managers, five staff physicians, five head nurses, two senior nurses and two quality officers. Fifty-eight percent was male. The average years of experience in the current function were 6.5 and ranged 1–25 years. The interviewees mentioned 58 prominent barriers and facilitators that influenced the implementation of the audit-based improvement actions (Table 2). Most factors were related to internal auditing (n = 22), implementation processes (n = 14) and professional (n = 9). Eight factors were organizational-related and, five social-related. Prominent auditing-related factors were quality of audit results, efficiency of the audit process and competence of internal auditors. A prominent implementation-related factor was the feasibility of improvement actions and a prominent professional-related factor was the attitude of healthcare providers for quality improvement. The two prominent social-related factors were leadership of the department heads and improvement culture; organizational structure for quality improvement was a prominent organizational-related factor. Generally, interviewees considered the audit results objective, relevant and recognizable due to the competence of the internal auditors, which facilitated the translation of the audit results into improvement actions. The interviewees wondered if the same audit results could be achieved with a less extensive audit system to reduce their amount of preparatory work. They also noted that a number of the intended patient safety improvement actions were difficult to implement due to the feasibility of the actions, the quality of both the patient safety improvement and implementation plan and the organizational structure for quality improvement (e.g. sufficient time, capacity, management support, information and communication technological [ICT] support). Despite these barriers, the interviewees also mentioned that the patient safety interventions implemented were due to the positive attitude and intrinsic motivation of the healthcare providers and the urgency of the department heads to improve that patient safety problem. According to the interviewees, a learning culture facilitated continuing patient safety improvement even when the improvement action proved inadequate (Table 2).

Table 2.

Perceived prominent facilitators and barriers for the implementation of improvement actions by the interview respondents

| Category | Sub-category | Factors | F | B | Illustrative quotes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Internal auditing (including revisit) | Quality of audit results |

|

✓ |

|

|

|

✓ | ||||

|

✓ | ✓ | |||

|

✓ | ✓ | |||

|

✓ | ||||

| Efficiency Process |

|

✓ |

|

||

|

✓ | ||||

|

✓ | ||||

|

✓ | ||||

|

✓ | ||||

|

✓ | ||||

|

✓ | ||||

|

✓ | ||||

|

✓ | ||||

|

✓ | ✓ | |||

| Revisit |

|

✓ | ✓ |

|

|

|

✓ | ||||

|

✓ | ||||

| Auditors |

|

✓ | Department manager: I think the audit has just been performed very thoroughly, with many specialized audits and quality topics. And I am just amazed, sometimes, that something comes up, that the audit team has discovered. | ||

|

✓ | ||||

|

✓ | ||||

|

✓ | ✓ | |||

| 2. Implementation process | Feasibility of improvement actions |

|

✓ |

|

|

|

✓ | ||||

|

✓ | ||||

|

✓ | ||||

|

✓ | ||||

|

✓ | ||||

|

✓ | ||||

|

✓ | ||||

|

✓ | ||||

| Implementation plan |

|

✓ | ✓ | From revisit report: The PDCA cycle is not complete yet. From bottom-up new initiatives arise (plan/do phase); there is no structural attention for implementation and quality assurance (check/act phase). | |

|

✓ | ✓ | |||

|

✓ | ||||

|

✓ | ✓ | |||

|

✓ | ||||

| 3. Professional | Attitude | Opinion that IA: |

|

||

|

✓ | ||||

|

✓ | ||||

|

✓ | ||||

|

✓ | ||||

|

✓ | ||||

|

✓ | ||||

| Motivation |

|

✓ | Head nurse: We immediately realized this improvement action by well-driven people in the right place, who want to do their work qualitatively well. | ||

|

✓ | ||||

|

✓ | ||||

| 4. Social | Leadership |

|

✓ | ✓ | Head nurse: I think of the strength of our current heads of the department, who are interested in quality improvement, with a positive attitude, no blaming culture, and you improve immediately. |

|

✓ | ✓ | |||

|

✓ | ||||

| Culture |

|

✓ | ✓ | Head nurse: We learn if we have not taken the right decisions. We say that afterwards, we could have chosen better for that approach and not for this approach. That is what you are learning and carries that with us for the next time. | |

|

✓ | ✓ | |||

| 5. Organizational (= hospital, department) | Organizational structure |

|

✓ |

|

|

|

✓ | ||||

|

✓ | ||||

|

✓ | ||||

|

✓ | ||||

|

✓ | ||||

|

✓ | ||||

|

✓ |

F = facilitator; B = barrier; IA = internal audit; PSI = patient safety improvement; EPD = electronic patient record; TCI = Team Climate Inventory; SMART = specific, measurable, attainable, realistic, timely; QI = quality improvement.

Discussion

We assumed that patient safety in hospital care would be significantly improved 15 months after the audit visit, as after the serious event in our hospital, there was a great sense of urgency among the healthcare providers to prevent such events, and they believed that patient safety auditing could be an effective intervention for assuring and improving the safety of hospital care [13]. Auditing is an appropriate method for identifying patient safety problems and their underlying causes and would aid the formulation of improvement actions tailored to the detected safety problems [7, 21]. However, in a previous study, we measured the effects of internal auditing in hospital care and observed no convincing effect [9]. In this process evaluation, we studied why the observed effects are small. In general, healthcare providers’ experiences with the internal audit process were positive, with the exception of the amount of departmental preparatory work, which was perceived as inefficient and disproportional in relation to the audit results. The audit results provided sufficient information for writing an improvement plan. The department heads and the healthcare providers implemented 21% of the intended improvement actions. Important factors that hindered the implementation of improvement actions were mainly in the follow-up phase: (1) the implementation time was <9 months instead of the planned 15 months; (2) it is unrealistic to expect to change healthcare providers’ behaviour and reorganize multidisciplinary care processes within 15 months; (3) there was limited implementation of interventions focused on specific patient safety problems, such as team training [22]; (4) an unfeasible improvement plan (e.g. too time-consuming and labour-intensive improvement actions) and (5) inadequate infrastructure for quality improvement (e.g. insufficient staff capacity and time, lack of quality evaluation data and ICT support).

Previous comparative studies, such as that by De Vos et al. [23] have also demonstrated difficulties in translating feedback information into effective actions; the same study also reported that the relatively short follow-up of 14 months resulted in no effects on quality improvement. Benning et al. [3] learned that great resources are necessary for effecting departmental change, and time is needed to entrenched patient safety improvements to have an impact on patient safety at department level. In most studies, data were typically gathered within 12 months of the intervention, while it is recognized that culture is a slow-changing phenomena [24]. Improved patient safety outcomes are observed when measurements are taken at least 2 years after the intervention [24]. The time required for healthcare providers to implement the quality improvement changes is underestimated [25]. Factors as staff capacity, time, data infrastructure, management and ICT support are well-known facilitators for successful quality improvement [24, 26].

A methodological strength of this study is the use of a mixed-method approach, which included a survey, interviews and document analysis for providing in-depth information on internal audit execution and experiences and the implementation of improvement actions [15]. This approach is recommended for capturing the effects of diffuse and complex innovations [27]. With the interviews more in-depth information is gathered regarding patient safety auditing; information that is difficult to capture with questionnaires [15]. Several limitations of this study have to be taken into account. The response to the questionnaire was just over 50%. This appears to be a low response rate; however, response rates of <20% among healthcare professionals are not uncommon [28, 29]. We also did not interview the internal auditors. Possibly, the auditors’ perspectives would provide new information on the audit process and the influencing factors.

This process evaluation resulted in a broad overview of factors that influence the effectiveness of patient safety auditing, which hospitals can use to support their staff to improve the audit process (Box 1).

Box 1. How to support staff to improve the audit process.

| Facilitators | Recommendations |

|---|---|

| Reliable audit results | Provide accurate feedback of the identified patient safety problems by objective, relevant, recognizable and reliable audit results. |

| Competent auditors | Detect patient safety problems by competent internal auditors who are also working at the hospital and who therefore know the care processes very well. |

| Efficient audit process | Prevent time consuming and labour intensive audit process by: tailor-made auditing on the quality level of the audited department/healthcare process, clear communication and coordination with other quality visits and measures. |

| Feasible improvement actions | Formulate and prioritize improvement actions with healthcare providers and stakeholders for feasibility and commitment. |

| Effective implementation | Choose tailor made, pragmatic implementation approach (e.g. PDCA cycle). Use quality officers’ support. |

| Leadership, attitude and learning culture | Combine leadership of the department heads, healthcare providers’ positive attitude and intrinsic motivation, and a learning culture for initiating and perpetuating improvements to address patient safety problems successfully. |

| Organization-wide advice and support | Give organization-wide advice and support for those responsible for improvement actions to achieve successfully implementation, among other things: calculating and facilitating the staff, time and finance required, the availability of quality improvement data, ICT support and sharing good patient safety improvement practices. |

PDCA = Plan, Do, Check, Act; ICT = Information and Communication Technology.

Conclusively, a well-constructed analysis and feedback of patient safety problems is insufficient to reduce the occurrence of poor patient safety outcomes. Our process evaluation showed that a lack of focus and support in the implementation of audit-based improvement actions prevents the completion of the PDCA improvement cycle. Quality improvement by patient safety auditing will remain limited.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the auditees and interviewees for their participation, Lilian van de Pijpekamp-Breen and Esmee Peters for their contribution in the processing of the data.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available at International Journal for Quality in Health Care online.

Authors' contributions

M.H.-S., M.Z., H.W., W.B., P.Jv.G. and G.P.W. designed the study. M.H.-S. collected the data. M.H.-S. and M.Z. analysed and interpreted the data, and drafted the manuscript. H.W., W.B., P.Jv.G. and G.P.W. assisted in interpreting the results and revising the manuscript for intellectual content. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interest statement

All authors work at Anonymous, whose audit system has been evaluated. Some bias could result from the hospital. Bias-preventing actions were registration of the study in the Dutch register for clinical trials, installation of an external advisory board for examining the integrity of the study group, independent data entry was performed by an administrative assistant, interviews were transcribed independently by a research assistant and were coded independently by a second researcher.

Ethical approval

The study protocol has been presented to the Medical Ethical Committee of the Anonymous (registration number:11 July 2011, CD/CMO 0793). They declared ethical approval was not required under the Dutch National Law. The study protocol was registered on 12 March 2012 in the Dutch Trial Registry of clinical trials (registration number: NTR3343).

Data sharing

On request available to the corresponding author.

References

- 1. Andermann A, Wu AW, Lashoher A et al. Case studies of patient safety research classics to build research capacity in low-and middle-income countries. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf 2013;39:553–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Dückers M, Faber M, Cruijsberg J et al. Safety and risk management interventions in hospitals. Med Care Res Rev 2009;66:90S–119S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Benning A, Ghaleb M, Suokas A et al. Large scale organisational intervention to improve patient safety in four UK hospitals: mixed method evaluation. BMJ 2011;342:d195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Shojania KG, Thomas EJ. Trends in adverse events over time: why are we not improving? BMJ Qual Saf 2013;22:273–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hysong SJ, Teal CR, Khan MJ et al. Improving quality of care through improved audit and feedback. Implement Sci 2012;7:45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ivers N, Jamtvedt G, Flottorp S et al. Audit and feedback: effects on professional practice and healthcare outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;6:CD000259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Walshe K, Freeman T. Effectiveness of quality improvement: learning from evaluations. Qual Saf Health Care 2002;11:85–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hanskamp-Sebregts M, Zegers M, Boeijen W et al. Effects of auditing patient safety in hospital care: design of a mixed-method evaluation. BMC Health Serv Res 2013;13:226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hanskamp-Sebregts M, Zegers M, Westert Gert P et al. Effects of patient safety auditing in hospital care: results of a mixed-method evaluation (part 1). Int J Qual Health Care 2018; 30. https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzy134 [Accepted May 17, 2018]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hulscher M, Laurant M, Grol R. Process evaluation on quality improvement interventions. Qual Saf Health Care 2003;12:40–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care 2007;19:349–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ogrinc G, Mooney S, Estrada C et al. The SQUIRE (Standards for QUality Improvement Reporting Excellence) guidelines for quality improvement reporting: explanation and elaboration. Qual Saf Health Care 2008;17:i13–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ouwens M, Roumen-Klappe E, Keyser A et al. One’s finger on the pulse. Internal audit system to monitor safety and quality of care (in Dutch). Med Contact (Bussum) 2008;38:1554–7. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Dutch Safety Board An inadequate goverance process: cardiac surgery in UMC St Radboud. Research after reporting of excessive mortality rates on 28 September 2005 (in Dutch), Den Haag; 2008. https://www.onderzoeksraad.nl/uploads/items-docs/364/rapport_hartchirurgie_sint_radboud.pdf (17 October 2017, date last accessed).

- 15. Pope C, Mays N. Qualitative Research in Health Care. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Netherlands Institute for Accreditation in Healthcare (in Dutch: NIAZ), The Netherlands: https://www.niaz.nl/english (17 October 2017, date last accessed).

- 17. Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol 2006;3:77–101. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hsieh H-F, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res 2005;15:1277–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Flottorp SA, Oxman AD, Krause J et al. A checklist for identifying determinants of practice: a systematic review and synthesis of frameworks and taxonomies of factors that prevent or enable improvements in healthcare professional practice. Implement Sci 2013;8:35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Baines R, Langelaan M, de Bruijne M et al. How effective are patient safety initiatives? A retrospective patient record review study of changes to patient safety over time. BMJ Qual Saf 2015;24:561–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Godlee F. How can we make audit sexy? BMJ 2010;340:c2324. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Weaver SJ, Lubomksi LH, Wilson RF et al. Promoting a culture of safety as a patient safety strategy: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med 2013;158:369–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. De Vos ML, Veer SN, Wouterse B et al. A multifaceted feedback strategy alone does not improve the adherence to organizational guideline-based standards: a cluster randomized trial in intensive care. Implement Sci 2015;10:95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Clay-Williams R, Nosrati H, Cunningham FC et al. Do large-scale hospital-and system-wide interventions improve patient outcomes: a systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res 2014;14:369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hughes RG. Advances in patient safety. Tools and strategies for quality improvement and patient safety In: Hughes RG (ed). Patient Safety and Quality: An Evidence-Based Handbook for Nurses. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US), 2008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kaplan HC, Provost LP, Froehle CM et al. The Model for Understanding Success in Quality (MUSIQ): building a theory of context in healthcare quality improvement. BMJ Qual Saf 2012;21:13–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Brown C, Hofer T, Johal A et al. An epistemology of patient safety research: a framework for study design and interpretation. Part 4. One size does not fit all. Qual Saf Health Care 2008;17:178–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Dykema J, Jones NR, Piché T et al. Surveying clinicians by web: current issues in design and administration. Evaluation & the health professions 2013;36:352–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Dobrow MJ, Orchard MC, Golden B et al. Response audit of an Internet survey of health care providers and administrators: implications for determination of response rates. J Med Internet Res 2008;10:e30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.