Abstract

Perceived victim credibility is a crucial factor in jury decision-making, especially in the context of child sexual assault cases where there are often no corroborating witnesses. Yet despite the importance of credibility and the expanding research in this area, there remains no unified understanding of what credibility is, what domains it encompasses and how it can be comprehensively measured. This article proposes a conceptual model of perceived victim credibility encompassing the five domains of accuracy, believability, competency, reliability and truthfulness. These domains are defined, distinguishing between the various sub-constructs based on the items they encompass. This model provides a theoretical framework for the development of an instrument to measure perceived victim credibility in future research studies. This is valuable for both researchers and professionals working in the area of child sexual assault in terms of understanding the construct of credibility and unifying the approach to measuring and comparing attitudes.

Key words: accuracy, believability, child sexual abuse, child sexual assault, competency, conceptual model, credibility, CSA, reliability, truthfulness

Introduction

Perceived victim credibility is one of the most influential factors in juror decision-making during cases of alleged child sexual assault. Specifically, victim credibility has been found to have a direct impact on court outcomes: that is, the less credible a jury considers the child victim to be, the less guilt is attributed to the defendant (Goodman‐Delahunty, Cossins, & O'Brien, 2010; Kaufmann, Drevland, Wessel, Overskeid, & Magnussen, 2003). The credibility of the victim is of particular importance in child sexual assault cases given the fact that the victim is often the sole witness to the event (Bottoms, Golding, Stevenson, & Yozwiak, 2007). Yet, despite witness credibility being of critical importance at trial, jurors are often left to decide on this issue with minimal guidance (Coyle, 2013). Ideally, jurors’ decision-making should be based solely on factual, admissible evidence provided during the trial. However, given the limited legal or ‘hard’ evidence that is commonly available in alleged cases of child sexual assault, there is considerable scope for jurors’ decisions to be influenced by extraneous factors or personal biases (Bottoms et al., 2007; Victorian Law Reform Commission, 2004).

Research in this area has proliferated in recent years, particularly with regard to the impact of victim and perceiver gender on perceptions of credibility. These extra-legal factors are considered two of the most influential determinants of credibility. Yet despite this expanding research base, there remains no universal definition or comprehensive understanding of what credibility is, and what domains this encompasses. Credibility has been diversely defined as the ‘quality in a witness which renders [his or her] evidence worthy of belief’ (Black, n.d.), ‘the extent to which a judge or jury believe that the witness is providing honest and accurate testimony’ (Nurcombe, 1986, p. 473), and the ‘ability to observe or remember facts and events about which the witness has given, is giving, or is to give evidence’ (Evidence Act, 2008 (Vic), Dictionary Pt. 1). Thus, while the concept of credibility seems like an intuitive one, there is a lack of consistent definition and understanding of the concept. In addition, there is considerable inconsistency in how credibility has been measured and conceptualised in past research, with studies measuring concepts such as ‘believability’, ‘honesty’ and ‘competency’. While these concepts have been interpreted synonymously with credibility, arguably they represent distinct facets of the overarching construct of ‘credibility’.

The aim of this article is to describe the development of a conceptual framework of perceived victim credibility. In order to achieve this, the sub-constructs or domains underlying credibility are identified, along with the items with which to measure these domains. This model may provide researchers and professionals working in criminal justice settings with an improved understanding of the constructs underlying credibility and will lead to a more unified approach to measuring and comparing perceptions of victim credibility.

Method

A recent systematic review was conducted regarding the impact of victim and perceiver gender on credibility, two of the most salient factors influencing perceptions of victim credibility (Voogt & Klettke, 2017). This review identified 27 papers that had measured perceived victim credibility, which informed the development of the current conceptual model. These measures were reviewed in order to develop an initial comprehensive item pool. Where existing measures utilised questions, these were rephrased into statements in order to measure items on a consistent Likert scale. In the interest of unifying items and utilising simple, consistent and straightforward language that is understandable to a lay audience (see Clarke & Watson, 1995), the term ‘alleged victim’ was changed to ‘this child’. The word ‘victim’ itself presumes that an offence has occurred and may therefore evoke a level of unconscious bias in respondents. Utilising the term ‘this child’ is an appropriately simplistic term and makes it clear to whom the item refers without using legal jargon.

In order to protect against an acquiescence bias, items were also reverse-coded at random. Where studies did not report the phrasing of items but provided an indication of what the item related to, new items were created by the authors consistent with this domain of credibility. For example, Davies, Patel, and Rogers (2013) reported utilising the item ‘dependable witness’, but the wording of this item was not available. With the view to creating a comprehensive item pool, a new item was developed consistent with the domain of dependability: ‘This child's testimony can be depended upon’. Appendix 1 presents the existing measurements of victim credibility identified within Voogt and Klette's (2017) review and summarises the development of the initial item pool.1.

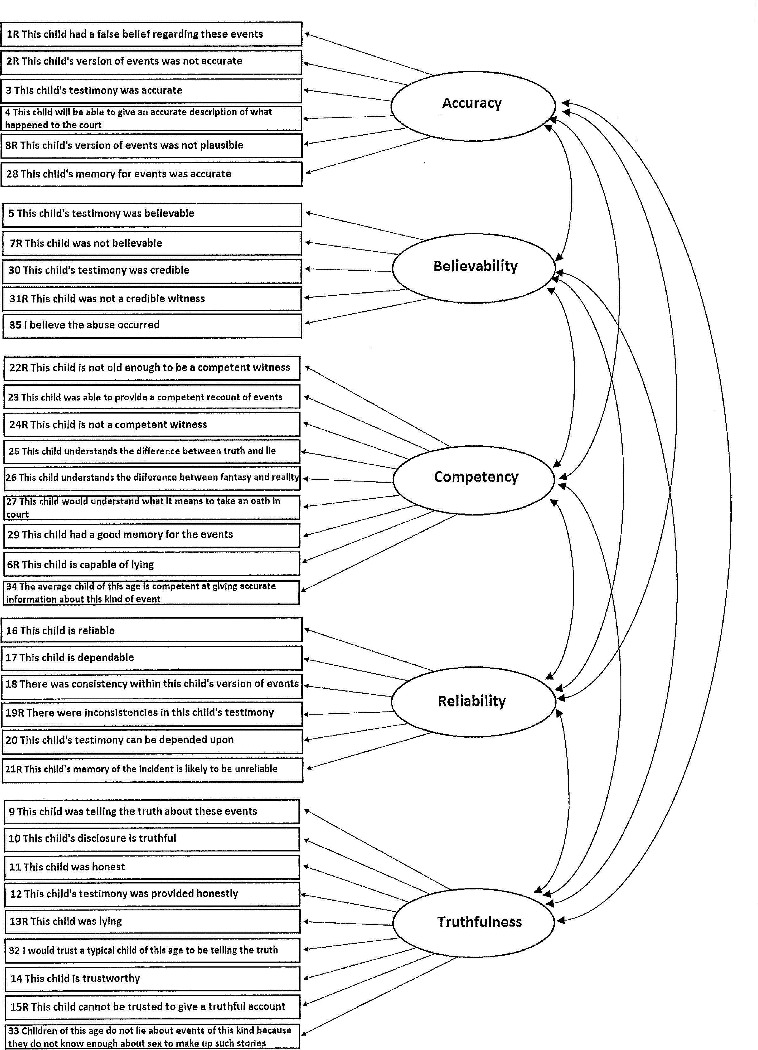

A total of 56 items were created and included in the initial item pool. Following the elimination of redundancies, a comprehensive but parsimonious item pool of 33 items remained. This pool was reviewed by an expert in the field of victim credibility and an additional 2 items were created by the authors based on the conceptual understanding of credibility: ‘This child's version of events was not plausible’ and ‘This child would understand what it means to take an oath in court’. The final 35 items included in the conceptual model are presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Conceptual model of perceived victim credibility.

Conceptual Model of Perceived Victim Credibility

A thematic analysis was used to produce a rudimentary synthesis of findings across the included literature (Braun & Clarke, 2006). This analysis suggests that victim credibility has previously been conceptualised as five distinct sub-constructs or domains: accuracy, believability, competency, reliability and truthfulness. Figure 1 provides an overview of the proposed model of perceived victim credibility.

Based on the thematic analysis, these sub-constructs are defined and distinguished. Based on the items comprising ‘accuracy’, this domain can be viewed as the perception that the child is correct in his or her description of events and that his or her testimony is consistent with the events that actually occurred. Truthfulness refers to the child's honesty in recounting events, and the perception that he or she is not maliciously or consciously lying. That is to say that a child could be viewed as truthful, but still hold a false belief and thus not be viewed as accurate. Reliability can be viewed as a distinct domain relating to consistency within the child's testimony and whether or not the child can be depended upon.

Believability has been defined as the child's ‘willingness to lie’ (Pozzulo, Dempsey, Maeder, & Allen, 2010), but may also be conceptualised as a more subjective, emotional aspect relating to the belief in the child's narrative. Items relating more specifically to ‘credibility’ were incorporated into this domain, consistent with the literature's use of the terms ‘believability’ and ‘credibility’ interchangeably (e.g. Bottoms, Davis, & Epstein, 2004; Wiley & Bottoms, 2009). Finally, competency relates to the child's cognitive capacities such as memory, and his or her understanding of sexual behaviour and the law.

Implications and Conclusion

While the literature on the perceived credibility of child victims continues to expand, and efforts have been made to identify different domains of credibility, no single framework or conceptualisation of these domains has yet provided a comprehensive overview of credibility. The conceptual model presented in this paper has been created utilising a systematic approach to identify items and synthesise them into broad domains or sub-constructs. As such, this work is a valuable contribution to the theoretical and conceptual understanding of credibility.

Based on the synthesis of past research pertaining to perceived victim credibility, five domains or sub-constructs of credibility are identified: accuracy, believability, competency, reliability and truthfulness. Despite many previous studies which have coneptualised and measured credibility as a unidimensional construct, the findings of the current study indicate that credibility is multifaceted and may not be accurately measured by utilising only a single domain or item.

It is important to establish a conceptual framework and the domains underlying perceived credibility before large-scale studies can be conducted on the factors that may influence this construct. The proposed model is valuable in both its relevance to professionals working in the area of child sexual assault and to those conducting research pertaining to child victim credibility. Further, this model provides a theoretical framework for the development of an instrument to measure perceived victim credibility in future research studies. There is a strong need to develop a valid and reliable scale to measure perceived victim credibility that addresses the identified domains within the model, and this is a valuable direction for future research. Future research may be conducted to test the hypothesised model using a factor analytical approach.

Appendix

Appendix 1

Table A1. Item pool development.

| Study | Original item phrasing | Rephrased item |

|---|---|---|

| Allen and Nightingale (1997) | Believability of the victim's testimony | This child's testimony was believable |

| Bornstein, Kaplan, and Perry (2007) | How truthful the disclosure was | This child's disclosure is truthful |

| Bottoms and Goodman (1994) (wording of items not reported) | Accuracy regarding the time frame of abuse events | |

| Accuracy regarding the number of abuse incidents | This child's version of events was not accurate | |

| Accuracy regarding description of the setting of abuse | ||

| Accuracy regarding description of the abuse | ||

| Truthfulness in answering questions | This child was truthful in responding to questions | |

| Consistency of testimony | There was consistency within this child's version of events | |

| Ability to distinguish fact from fantasy | This child understands the difference between fantasy and reality | |

| Likelihood that the witness fabricated allegations | It is likely that this child fabricated the allegations | |

| Bottoms, Nysse-Carris, Harris, and Tyda (2003) | Whether the victim honestly believed the abuse charge | This child had a false belief regarding these events |

| Likelihood that [the child] fabricated the abuse charge | It is likely that this child fabricated the abuse charge | |

| Brigham (1998) | Likelihood that [the victim] is telling the truth | It is likely that this child is telling the truth |

| Davies et al. (2013) (wording of items not reported) | Dependable witness | This child's testimony can be depended upon |

| Reliable witness | There were inconsistencies in this child's testimony | |

| Trustworthy account | This child provided a trustworthy account of events | |

| Victim's statement credible | This child's statement was credible | |

| Victim memory | This child had a good memory for the events | |

| Victim's statement accurate | This child was able to provide a competent recount of events | |

| Victim truthful | This child was truthful | |

| Davies and Rogers (2009) | How competent do you think the average child of [victim name]'s age is at giving accurate information about this kind of event? | The average child of this age is competent at giving accurate information about this kind of event |

| How much do you believe that [victim name] will be able to give an accurate description of what happened to the police? | This child will be able to give an accurate description of what happened to the court | |

| To what extent do you believe that [victim name] is telling the truth about this event? | This child was telling the truth about these events | |

| To what extent would you trust a typical child of [victim name]'s age to be telling the truth? | I would trust a typical child of this age to be telling the truth | |

| Children of [victim name]'s age do not lie about events of this kind because they do not know enough about sex to make up such stories | Children of this age do not lie about events of this kind because they do not know enough about sex to make up such stories | |

| Esnard and Dumas (2013) | Do you think that [victim name]'s testimony is credible? | This child's testimony was credible |

| Golding, Alexander, and Stewart (1999) | Belief of the witness [victim] testifying | I believe the abuse occurred |

| McCauley and Parker (2001) (wording of items not reported) | Credibility | This child was a credible witness |

| Honesty | This child's testimony was provided honestly | |

| Memory | This child is not a competent witness | |

| Nunez, Kehn, and Wright (2011) | [The victim] knows the difference between truth and lie | This child understands the difference between truth and lie |

| [The victim] is trusted by adults | This child is trustworthy | |

| [The victim] can be trusted | This child can be trusted | |

| S/he's [the victim] reliable and dependable | This child is reliable | |

| This child is dependable | ||

| [The victim] is honest | This child was honest | |

| O'Donohue, Elliott, Nickerson, and Valentine (1992) | The child [victim] was telling the truth. | The child was telling the truth |

| O'Donohue and O'Hare (1997) | [Victim name] is telling the truth | The child was telling the truth |

| O'Donohue, Smith, and Schewe (1998) | The child [victim] is telling the truth | The child was telling the truth |

| Pozzulo et al. (2010) | How accurate do you find the alleged victim's testimony? | This child's testimony was accurate |

| How believable do you find the alleged victim's testimony? | This child's testimony was believable | |

| How credible do you find the alleged victim's testimony? | This child's testimony was credible | |

| How reliable do you find the alleged victim's testimony? | This child's testimony was reliable | |

| How truthful do you find the alleged victim's testimony? | This child's testimony was truthful | |

| Rogers and Davies (2007) (wording of items not reported) | Typical child accuracy | A typical child of this age would have an accurate memory for such events |

| Victim accuracy | This child's memory for events was accurate | |

| Victim truth | This child was lying | |

| Rogers, Josey, and Davies (2007) | [Victim name] would not be able to lie about this event because a child of her age would be too naïve to know about such sexual details | This child would not be able to lie about this event because a child of this age is too naïve to know about sexual details |

| An account of this type of event given by a child of [victim name]'s age will be accurate | An account of this type of event given by a child of this age will be accurate | |

| A child of [victim name]'s age can competently give an accurate account of this type of event | A child of this age can competently give an accurate account of this type of event | |

| Rogers, Lowe, and Boardman (2014) | [Victim name]'s memory of the incident is likely to be unreliable | This child's memory of the incident is likely to be unreliable |

| [Victim name] is telling the truth about what happened | This child was telling the truth about these events | |

| Rogers, Wczasek, and Davies (2011) (wording of items not reported) | Victim truthfulness | This child was truthful |

| Victim age truthfulness | This child cannot be trusted to give a truthful account | |

| Victim age competence | This child is not old enough to be a competent witness | |

| Victim age lie/naïvety | This child is capable of lying | |

| Rubin and Thelen (1996) | How likely is it that the victim is telling the truth? | It is likely that the child is telling the truth |

| Wiley and Bottoms (2009) | How credible do you think [victim name] was (in other words, how believable was [victim name])? | This child was not a credible witness |

| This child was not believable |

Note

It is noted that numerous studies identified within Voogt and Klettke's (2017) review do not specify how credibility was measured, further than suggesting, for example, that credibility was rated on a scale from 1 = not at all believable to 6 = extremely believable (Bottoms et al., 2004). As such, these studies are not included in Table A1 in Appendix 1.

References

- Allen L. A., & Nightingale N. N. (1997). Gender differences in perception and verdict in relation to uncorroborated testimony by a child victim. Journal of Offender Rehabilitation, 24(3/4), 101–116. [Google Scholar]

- Black H. C. (n.d.). Black's Law Dictionary. Retrieved from http://thelawdictionary.org/credibility/

- Bornstein B. H., Kaplan D. L., & Perry A. R. (2007). Child abuse in the eyes of the beholder: Lay perceptions of child sexual and physical abuse. Child Abuse and Neglect, 31(4), 375–391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bottoms B. L., Davis S. L., & Epstein M. A. (2004). Effects of victim and defendant race on jurors’ decisions in child sexual abuse cases. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 34(1), 1–33. [Google Scholar]

- Bottoms B. L., Golding J. M., Stevenson M. C., & Yozwiak J. A. (2007). A review of factors affecting jurors’ decision in child sexual abuse cases. In Toglia M., Read J. D., Ross D. F., & Lindsay C. L. (Eds.), Handbook of eyewitness psychology: Vol. 1: Memory for events (pp. 509–543). Mahwah, New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- Bottoms B. L., & Goodman G. S. (1994). Perceptions of children's credibility in sexual assault cases. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 24(8), 702–732. [Google Scholar]

- Bottoms B. L., Nysse-Carris K. L., Harris T., & Tyda K. (2003). Jurors’ perceptions of adolescent sexual assault victims who have intellectual disabilities. Law and Human Behavior, 27(2), 205–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun V., & Clarke V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. [Google Scholar]

- Brigham J. C. (1998). Adults’ evaluations of characteristics of children's memory. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 19(1), 15–39. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke L. A., & Watson D. (1995). Constructing validity: Basic issues in objective scale development. Psychological Assessment, 7(3), 309–319. [Google Scholar]

- Coyle I. R. (2013). How do decision makers decide when witnesses are telling the truth and what can be done to improve accuracy in making assessments of witness credibility? Report to the Criminal Lawyers Association of Australian and New Zealand. Retrieved from http://bond.edu.au/prod_ext/groups/public/@pub-law-gen/documents/image/bd3_027359.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Davies M., Patel F., & Rogers P. (2013). Examining the roles of victim–perpetrator relationship and emotional closeness in judgments toward a depicted child sexual abuse case. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 28(5), 887–909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies M., & Rogers P. (2009). Perceptions of blame and credibility toward victims of childhood sexual abuse: Differences across victim age, victim–perpetrator relationship, and respondent gender in a depicted case. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse, 18(1), 78–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esnard C., & Dumas R. (2013). Perceptions of male victim blame in a child sexual abuse case: Effects of gender, age and need for closure. Psychology Crime & Law, 19(9), 817–844. [Google Scholar]

- Evidence Act 2008 (Vic). [Google Scholar]

- Golding J. M., Alexander M. C., & Stewart T. L., (1999). The effect of hearsay witness age in a child sexual assault trial. Psychology, Public Policy, and Law, 5(2), 420–438. [Google Scholar]

- Goodman‐Delahunty J., Cossins A., & O'Brien K. (2010). Enhancing the credibility of complainants in child sexual assault trials: The effect of expert evidence and judicial directions. Behavioral Sciences & the Law, 28(6), 769–783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufmann G., Drevland G. C., Wessel E., Overskeid G., & Magnussen S. (2003). The importance of being earnest: Displayed emotions and witness credibility. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 17(1), 21–34. [Google Scholar]

- McCauley M. R., & Parker J. F. (2001). When will a child be believed? The impact of the victim's age and juror's gender on children's credibility and verdict in a sexual-abuse case. Child Abuse and Neglect, 25(4), 523–539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nunez N., Kehn A., & Wright D. B. (2011). When children are witnesses: The effects of context, age and gender on adults’ perceptions of cognitive ability and honesty. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 25(3), 460–468. [Google Scholar]

- Nurcombe B. (1986). The child as witness: Competency and credibility. Journal of the American Academy of Child Psychiatry, 25(4), 473–480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Donohue W., Elliott A. N., Nickerson M., & Valentine S. (1992). Perceived credibility of children's sexual abuse allegations: Effects of gender and sexual attitudes. Violence and Victims, 7(2), 147–156. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Donohue W., & O'Hare E. (1997). The credibility of sexual abuse allegations: Child sexual abuse, adult rape, and sexual harassment. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 19(4), 273–279. [Google Scholar]

- O'Donohue W., Smith V., & Schewe P. (1998). The credibility of child sexual abuse allegations: Perpetrator gender and subject occupational status. Sexual Abuse: Journal of Research and Treatment, 10(1), 17–24. [Google Scholar]

- Pozzulo J. D., Dempsey J., Maeder E., & Allen L. (2010). The effects of victim gender, defendant gender and defendant age on juror decision making. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 37(1), 47–63. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers P., & Davies M. (2007). Perceptions of victims and perpetrators in a depicted child sexual abuse case: Gender and age factors. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 22(5), 566–584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers P., Josey N., & Davies M. (2007). Victim age, attractiveness and abuse history as factors in the perception of a hypothetical child sexual abuse case. Journal of Sexual Aggression, 13(2), 121–137. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers P., Lowe M., & Boardman M. (2014). The roles of victim symptomology, victim resistance and respondent gender on perceptions of a hypothetical child sexual abuse case. Journal of Forensic Practice, 16(1), 18–31. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers P., Wczasek R., & Davies M. (2011). Attributions of blame in a hypothetical internet solicitation case: Roles of victim naivety, parental neglect and respondent gender. Journal of Sexual Aggression, 17(2), 196–214. [Google Scholar]

- Rubin M. L., & Thelen M. H. (1996). Factors influencing believing and blaming in reports of child sexual abuse: Survey of a community sample. Journal Of Child Sexual Abuse, 5(2), 81–100. [Google Scholar]

- Victorian Law Reform Commission (2004). Sexual offences: Final report. Melbourne, Victoria: Victorian Law Reform Commission. [Google Scholar]

- Voogt A., & Klettke B. (2017). The effect of gender on perceptions of credibility in child sexual assault cases: A systematic review. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse, 26(2), 195–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiley T. R. A., & Bottoms B. L. (2009). Effects of Defendant Sexual Orientation on Jurors’ Perceptions of Child Sexual Assault. Law and Human Behavior, 33(1), 46–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]