Abstract

Background:

Knee osteoarthritis (OA) affects an estimated 1 in 5 individuals older than 45 years of age in the United Kingdom. Previous studies have suggested that germanium-infused garments may provide improved clinical outcomes in OA. Germanium-embedded (GE) knee sleeves embrace this fabric technology.

Purpose:

To assess the outcomes of GE knee sleeves for patients with knee OA.

Study Design:

Cohort study; Level of evidence, 2.

Methods:

This study was undertaken at a hospital in the United Kingdom. Patients who had radiographic features of OA, experienced knee pain for at least 6 months, and opted for nonsurgical intervention were included. Patients were recruited over 3 months. The University of California, Los Angeles activity score, Lysholm score, visual analog scale (VAS) score, and Oxford Knee Score (OKS) were collected at monthly intervals for 6 months. Patients were followed to determine their compliance with wearing the knee sleeves at all times, as advised, and whether any adverse effects had occurred.

Results:

A total of 50 participants were recruited for the study; 4 participants were excluded due to pain and were converted to surgical management. Therefore, 46 patients were analyzed and placed into 2 groups according to severity of OA, as classified by the Kellgren-Lawrence system: group A had grade 1 or 2 OA, and group B had grade 3 or 4 OA. There were 25 patients in group A and 21 in group B. Improvements were seen in OKS, VAS, and Lysholm scores in both groups. Clinically significant improvements were seen in group A only for OKS (mean increase, 14), VAS (mean decrease, 4.1), and Lysholm (mean increase, 17.2) scores. These results were also statistically significant (OKS, P = 5.8 × 10-7; VAS, P = 7.7 × 10-12; Lysholm, P = 4.2 × 10-11). The data from this study demonstrated that GE knee sleeves gave better outcomes for patients with grades 1 and 2 OA compared with patients with more advanced disease, which is consistent with previous studies. A total of 3 patients reported skin irritation, which resolved with simple skin ointment application. No patients reported infection, deep vein thrombosis, or circulation problems.

Conclusion:

GE knee sleeves could play an important role in optimizing nonsurgical management of patients with knee OA, especially patients with grades 1 and 2 OA, as demonstrated by the clinically significant improvements.

Keywords: knee, osteoarthritis, sleeve, management, germanium

Osteoarthritis (OA) is a common condition, and knee OA affects an estimated 1 in 5 people older than 45 years of age in the United Kingdom.2 Patients with OA experience pain, decreased mobility and function, muscle weakness, and deterioration in ability to accomplish activities of daily living.25 Not only can OA cause a substantial loss in quality of life, but it also has a vast financial impact on the National Health Service (NHS). More than 8.75 million people 45 years of age and older (one-third of the UK population) have required treatment for OA.1,20 The prevalence of OA is expected to continue to rise with increasing life expectancies and increasing levels of risk factors such as obesity.31

Pain is the main symptom associated with OA; nearly 80% of patients with arthritis experience pain most days, and 1 in 8 patients describe their pain as unbearable.7 It has been found that depression is 4 times as common in patients with chronic pain compared with those who are pain-free; in keeping with this, around 20% of people with OA experience symptoms of depression and anxiety.11,22,27

Treatment Options for Knee OA

The main goals of treating knee OA are improvement or maintenance of mobility and function, relief of pain and inflammation, and prevention of declining quality of life. Although treatment options for knee OA have been widely implemented and researched, the optimum treatment or combinations of treatment remain unclear.25

The efficacy of total knee replacement (TKR) for improving pain and function has been proven.23 However, surgery is not suitable for all candidates. This, in particular, applies to younger patients who lead more active lifestyles; younger people have a 5-fold increased risk that the replacement will wear out, and they are also more likely to require a revision surgery due to their longer life expectancy.3 Furthermore, TKR may not be a long-lasting solution because repeat surgery may be required within 2 decades of life.25 As such, it is crucial to optimize the available nonoperative managements options. Treatments are needed that can effectively relieve pain and improve function in order to delay surgery.25 This was emphasized in the 2014 National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines, which highlight that OA treatment should take a holistic approach to management and include, at its simplest, patient education, physical activity, weight loss, and devices such as knee braces and walking aids.26

Current Evidence for Knee Braces

In 2017, Lee et al21 conducted a literature review and analyzed 14 studies that compared offloading knee braces versus other forms of treatment. Offloading braces aim to unload the diseased compartment, whereas neutral braces and sleeves immobilize and stabilize the knee joint by providing tactile feedback from the skin. The former has been shown to be helpful for unicompartmental arthritis, with minor reductions in pain and increased function compared with controls. It was found that knee braces are a cost-effective measure that can delay the need for surgery over an 8-year period and could potentially replace the need for surgery altogether.21 Lee et al21 also demonstrated that knee braces drastically affect a patient’s quality of life and, as per NICE guidelines for management of knee OA, should be used in combination with other standard treatments. Certainly, although more research is needed to compare the efficacy of different types of knee braces, early data suggest that anti-inflammatory sleeve technology using materials such as germanium may also be beneficial in managing knee OA.

Germanium-Embedded Knee Sleeve

The Incrediwear Cred40 knee sleeve (Figure 1) is embedded with carbonized charcoal and germanium. Germanium is a nontoxic semiconductor metalloid located between tin and silicone in the periodic table. Since its discovery in 1886, germanium has been widely used in electronics and optics.28 Semiconductors such as germanium differ from metals in that as the temperature of semiconductors increases, their resistance decreases. This is a result of germanium having more “free” electrons at certain temperatures, allowing for a higher conductivity. It is theorized that embedding germanium into cotton garments is an effective way to use the transdermal effect to create a micro electromagnetic field, leading to increased circulation and affecting the inflammatory process.20 Previous low-level observational studies have suggested that germanium-infused garments may provide improved clinical outcomes in osteoarthritis. Germanium-embedded (GE) knee sleeves embrace this fabric technology.

Figure 1.

The Incrediwear Cred40 Knee Sleeve.

Aims of this Study

This is a service evaluation study that aims to assess the clinical outcomes of GE knee sleeves for patients with knee OA using a variety of patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs).

Methods

This project is a service evaluation, via a cohort study, of the management of knee OA undertaken at a hospital in the United Kingdom. Quantitative methods via questionnaire were used for data collection as standard practice in keeping with current clinical practice. The questionnaire included the following scoring systems related to evaluating the knee: University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) activity score, which measures current activity level30; Lysholm score, which measures ability to manage in everyday life19; visual analog scale (VAS) score, which measures the amount of pain felt over the past 24 hours13; and Oxford Knee Score (OKS), which measures function and pain.10 In addition, a subjective semistructured interview was conducted during follow-up visits to determine whether patients were happy with the sleeve, whether any adverse effects had occurred, and whether patients had been wearing the sleeve all the time as advised. Ethical approval was obtained for this study.

Participants and Recruitment

The study included both male and female patients who had been prescribed a GE knee sleeve following consultation in an orthopaedic clinic and radiographic assessment between January and March of 2018. Radiographic features of OA, as characterized by the Kellgren-Lawrence (KL) system, must have been present and the patient must have had knee pain for at least 6 months.18 To be considered for inclusion, the patient must have opted for nonsurgical interventions for managing his or her knee OA. Excluded were patients who opted for surgery or who had no OA changes on knee radiographs or magnetic resonance imaging scans. All participants were given the same model of knee sleeve, varying in sizes (M to XXL) as required. Patient care was in no way altered due to the conduct of this study. No patients involved in this study received additional management of physical therapy or injection therapy. All participants were fully informed about what the study involved and were told that their care would not be affected if they declined to be involved. In addition, all participants provided written informed consent.

Data Collection

The same questionnaire was given to patients when they were first given the knee sleeve (ie, at baseline) and every month thereafter for 6 months. Patients were instructed to wear the sleeve at all times. Data collection was completed by September 2018.

Data Analysis

Variance in the results of continuous data during the 6 months was analyzed by use of repeated-measures analysis of variance for continuous data and chi-square test for nominal categorical data. SPSS version 23.0 (IBM) was used to analyze the data. Statistical significance was set at P < .05. The data were independently analyzed by 2 members of the research team (K.M., P.L.) to reduce potential error and bias.

Where appropriate, data were divided into group A and group B for analysis of subgroups. Group A represented patients with grade 1 or grade 2 OA as per the KL system. Similarly, group B represented patients with grade 3 or grade 4 OA. Participants who withdrew from the study at any point during the 6-month period were excluded from data analysis.

During each follow-up appointment, patients were asked whether they had experienced any adverse events. Potential adverse events were listed as skin complications, infection, change of treatment (such as the need for surgery or injections), decreased range of movement, and other.

Results

Demographic Information

We recruited 50 individuals for this service evaluation. Of these, 4 participants were excluded due to pain and were converted to surgical management. This resulted in a final response rate of 94%. The mean patient age was 62 years in both group A and group B (Table 1).

Table 1.

Participant Age and Sexa

| Group A | Group B | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | Male | Female | Male | Female |

| 40-49 | 1 (0.04) | 1 (0.04) | 1 (0.05) | 0 |

| 50-59 | 4 (0.16) | 2 (0.08) | 3 (0.14) | 3 (0.14) |

| 60-69 | 8 (0.33) | 6 (0.25) | 6 (0.29) | 4 (0.19) |

| 70-79 | 1 (0.04) | 2 (0.08) | 0 | 4 (0.19) |

| Total | 14 (0.56) | 11 (0.44) | 10 (0.48) | 11 (0.52) |

aValues are expressed as n (%). There were 25 participants in group A and 21 in group B.

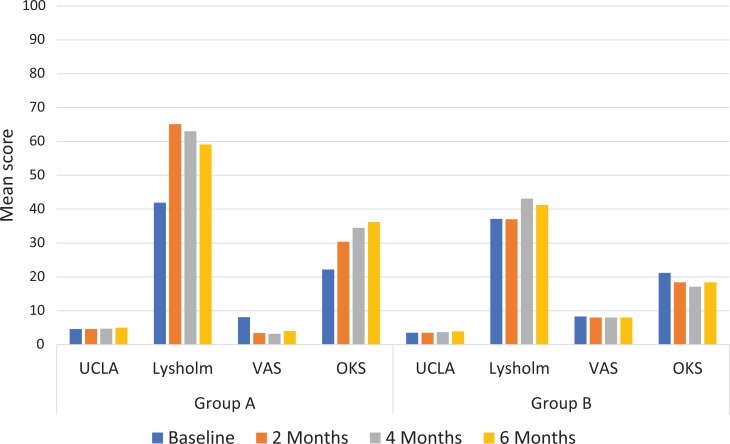

Tables 2 and 3 provide the mean or median result for each parameter at baseline, 2 months, 4 months, and 6 months for groups A and B, respectively. The same data are presented in Figure 2. Appendix Table A1 provides results for every month of the study as well as P values for the differences between baseline and 6 months.

Table 2.

Comparison of Mean or Median Values for Each Scoring System at Baseline, 2 Months, 4 Months, and 6 Months for Group Aa

| Scoring System | Baseline | 2 Months | 4 Months | 6 Months | Difference (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UCLA score | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 0 |

| Lysholm score | 41.9 | 65.1 | 63.0 | 59.1 | 17.2 (41)b |

| VAS score | 8.1 | 3.4 | 3.2 | 4.0 | –4.1 (–51)b |

| Oxford Knee Score | 22.2 | 30.4 | 34.5 | 36.2 | 14.0 (63)b |

aValues are expressed as means for all scores except the UCLA score, where median is used because the data are categorical. UCLA, University of California, Los Angeles; VAS, visual analog scale.

bA significant difference (P < .05) was found between the score at baseline compared with 6 months.

Table 3.

Comparison of Mean or Median Values for Each Scoring System at Baseline, 2 Months, 4 Months, and 6 Months for Group Ba

| Scoring System | Baseline | 2 Months | 4 Months | 6 Months | Difference (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UCLA score | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 0 |

| Lysholm score | 37.1 | 37.0 | 43.1 | 41.2 | 4.1 (11) |

| VAS score | 8.3 | 8.0 | 8.0 | 8.0 | –0.3 (–4) |

| Oxford Knee Score | 21.2 | 18.4 | 17.1 | 18.4 | 2.8 (13) |

aValues are expressed as means for all scores except the UCLA score, where median is used because the data are categorical. UCLA, University of California, Los Angeles; VAS, visual analog scale. No significant difference (P < .05) was found between the scores at baseline compared with 6 months for any of the scoring systems.

Figure 2.

Results for University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) score, Lysholm score, visual analog scale (VAS) score, and Oxford Knee Score (OKS) at baseline, 2 months, 4 months, and 6 months for groups A and B.

UCLA Score

No change was found in the median UCLA score between baseline and 6 months for either group. Group A had a median of 5 every month; throughout the 6 months, group A had a higher median than group B, whose median was 4. No statistically significant difference in UCLA score was found during the 6-month period for either group.

Lysholm Score

Group A had a 17.2-point increase (41%) in mean Lysholm score from baseline to 6 months. This difference was statistically significant (P = 4.2 × 10-11). Group B had a 4.1-point increase (11%) in mean Lysholm score from baseline to 6 months. No statistically significant difference in results was found between baseline and 6 months.

VAS Score

A decrease in VAS score of 4.1 was found in group A, equating to a 51% reduction in score. A statistically significant difference was found between the baseline score and every time the scores were retaken, including between baseline and 6 months (P = 7.7 × 10-12). In group B, the VAS score decreased by 0.34, which was a 4% decrease. No statistically significant difference was found in group B.

Oxford Knee Score

In group A, an increase of 14.0 (63%) was found for the OKS. A statistically significant difference was found in results between baseline and every time thereafter that the score was retaken, including between baseline and 6 months (P = 5.8 × 10-7). For group B, an increase of 2.8 (13%) was found for the OKS, and no statistically significant difference was found between baseline and 6 months.

Complications

A total of 3 patients reported skin irritation, which resolved with a simple skin ointment. A further 5 patients reported that the knee sleeve became loose after 2 months of use, which could potentially be due to reduced inflammation around the knee. A common issue was the sleeve becoming loose after being washed. To reduce this, it is recommended that the sleeve be machine dried to help maintain its shape. No infection, deep vein thrombosis, or circulation problems were reported.

Discussion

This project evaluated the use of GE knee sleeves as a nonoperative management option in patients with OA who had opted out of surgery. Specifically, we assessed the difference that the knee sleeve makes to patients with milder OA (KL grades 1 and 2) compared with patients who have more severe OA (KL grades 3 and 4). A variety of PROMs were used to collect the data. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to examine the use of GE knee sleeves in patients with knee OA.

This study found that over 6 months of using the GE knee sleeves, patients with low-grade OA had a mean increase of 14 points in the OKS. Previous studies found that the minimum clinically important difference (MCID) value for the OKS ranged from 5 to 9.4,6,15 Although these studies focused on patients who had undergone knee replacement rather than patients who used a knee sleeve, it can be deduced that our results likely found a clinically significant improvement in OKS, and therefore a clinically significant improvement in pain and function, in patients with low-grade OA. We found a 4.1-point reduction (51%) in VAS pain score in patients with low-grade OA. Previous studies have found the MCID for VAS to range from 2.1 to 2.3, meaning that a clinically significant reduction in VAS score, and therefore pain, was found in patients with low-grade OA.9,17 In addition, the MCID for the Lysholm score has been reported as 10.1, meaning that this study also found a clinically significant different in Lysholm score in patients with low-grade OA, with a mean difference of 17.2 reported.16

The main goal of nonoperative management of knee OA is to reduce pain and improve function and quality of life.29 A recent literature review found that the current research demonstrates the effectiveness of knee braces as a treatment for knee OA; however, most studies assessed patients over a short period (6 months).24 The literature review also noted that the use of knee braces is surprisingly low given that they are part of the NICE guidelines for recommended management of knee OA.24,26 Although previous studies have questioned the effectiveness of knee braces in the treatment of OA, the findings of the current study support their use, particularly in patients with low-grade OA.8,12

Most Effective in Low-Grade OA

A pattern emerged from the data demonstrating that GE knee sleeves gave better outcomes for patients with grades 1 and 2 OA compared with patients who had more advanced disease. Our study is not the first to find this trend.29 It can be inferred from our findings that the GE knee sleeve is an effective treatment option in patients with low-grade disease. The knee sleeve can be viewed either as a way of allowing these patients to manage their OA by controlling their symptoms until a time when the pain or changes in function become so extreme that surgery is necessary or as a way of potentially avoiding the need for surgery altogether.21 As stated above, this study found clinically significant improvements in OKS, VAS, and Lysholm scores for patients with low-grade OA. In contrast, participants with more severe OA did not achieve a significant improvement in symptoms with the knee sleeve, and there was potentially still evidence of disease progression.

High Compliance Rate

The dropout rate of this study was very low (8%) compared with other studies involving knee braces.5,14 This dropout rate suggests that the GE knee sleeve is a treatment option to which most patients will adhere, and the low number of complications highlights that the GE knee sleeve is a safe treatment method. As previously suggested by Lee et al,21 the current study included regular follow-up appointments to monitor for any complications, to check whether patients were fitting the sleeve correctly, and to correct problems with fitting in order to avoid soft tissue injuries and increase chances of successful treatment. However, given that this knee sleeve is easy to use and less bulky than the one used in the Lee et al21 study, follow-up may not be needed as often as every month, which would save time and money.

Recommendations for Future Research

In keeping with results of previous studies, our findings support the use of a knee sleeve for short-term use in knee OA; however, more research looking into the long-term outcomes of knee sleeves is required.24 It would be of interest to compare the use of the GE knee sleeve with other knee sleeves or braces used in nonoperative treatment of OA. We also recommend further research to compare the outcomes of patients who use GE knee sleeves versus those patients who undergo surgery.

Strengths and Limitations

Limitations of the study include the nonrandomized study design, the small sample size, the potential for recall bias, and the possibility that patients did not comply fully. In addition, the lack of a control group makes it difficult to judge the extent to which a placebo effect contributed to the result. The strengths of the study are the regular patient follow-up and the low dropout rate.

Conclusion

In the United Kingdom, knee OA continues to be a leading cause of morbidity and cost to the health service, and the clinical and economic burden of OA is predicted to increase. Optimization of current nonoperative management is important in improving quality of life and delaying the need for surgical intervention. This is the first study to assess the outcomes of GE knee sleeves in patients with knee OA. Our results confirm that GE knee sleeves could play an important role in managing patients with knee OA, as demonstrated by the clinically significant improvements in OKS, VAS, and Lysholm scores.

Appendix

Table A1.

Results of UCLA, Lysholm, VAS, and Oxford Knee Scoresa

| Group | Baseline | 1 Month | 2 Months | 3 Months | 4 Months | 5 Months | 6 Months | Difference (%) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group A | |||||||||

| UCLA score | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 0 | .216 |

| Lysholm score | 41.9 | 62.0 | 65.1 | 62.4 | 63.0 | 60.4 | 59.1 | 17.2 (41) | 4.2 × 10-11 b |

| VAS score | 8.1 | 4.5 | 3.4 | 3.7 | 3.2 | 3.4 | 4.0 | –4.1 (–51) | 7.7 × 10-12 b |

| Oxford Knee Score | 22.2 | 27.8 | 30.4 | 37.4 | 34.5 | 36.0 | 36.2 | 14.0 (63) | 5.8 × 10-7 b |

| Group B | |||||||||

| UCLA score | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 0 | .14 |

| Lysholm score | 37.1 | 37.9 | 37.0 | 40.2 | 43.1 | 47.2 | 41.2 | 4.1 (11) | ≥.999 |

| VAS score | 8.3 | 8.4 | 8.0 | 7.2 | 8.0 | 8.1 | 8.0 | –0.3 (–4) | ≥.999 |

| Oxford Knee Score | 21.2 | 19.9 | 18.4 | 15.0 | 17.1 | 15.7 | 18.4 | 2.8 (13) | ≥.999 |

aScores are given for group A and group B at baseline and every month thereafter up until 6 months. Values are expressed as means for all scores except the UCLA score, where median is used because the data are categorical. The difference in scores between baseline and 6 months is given, as is the P value for comparison between results at baseline and 6 months. UCLA, University of California, Los Angeles; VAS, visual analog scale.

bP < .05.

Footnotes

The authors declared that there are no conflicts of interest in the authorship and publication of this contribution. AOSSM checks author disclosures against the Open Payments Database (OPD). AOSSM has not conducted an independent investigation on the OPD and disclaims any liability or responsibility relating thereto.

Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the National Health Service Health Research Authority (IRAS project ID: 259756).

References

- 1. Arthritis Research UK. Osteoarthritis in general practice. https://healthinnovationnetwork.com/resources/osteoarthritis-in-general-practice-arthritis-research-uk-2013/. Accessed December 29, 2018.

- 2. Arthritis Research UK. Prevalence of osteoarthritis in England local authorities: Tower Hamlets. https://www.versusarthritis.org/media/13271/tower-hamlets-oa.pdf. Accessed December 29, 2018.

- 3. Bayliss L, Culliford D, Monk A, et al. The effect of patient age at intervention on risk of implant revision after total replacement of the hip or knee: a population-based cohort study. Lancet. 2017;389:1424–1430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Beard DJ, Harris K, Dawson J, et al. Meaningful changes for the Oxford hip and knee scores after joint replacement surgery. J Clin Epidemiol. 2015;68(1):73–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Brouwer RW, van Raaij TM, Verhaar JA, Coene LN, Bierma-Zeinstra SM. Brace treatment for osteoarthritis of the knee: a prospective randomized multi-centre trial. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2006;14:777–783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Clement ND, MacDonald D, Simpson AH. The minimal clinically important difference in the Oxford Knee Score and Short Form 12 score after total knee arthroplasty. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2016;24(11):3696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Conaghan PG, Porcheret M, Kingsbury SR, et al. Impact and therapy of osteoarthritis: the Arthritis Care OA Nation 2012 survey. Clin Rheumatol. 2015;34(9):1581–1588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Crawford DC, Miller LE, Block JE. Conservative management of symptomatic knee osteoarthritis: a flawed strategy. Orthop Rev. 2013;5(1):5–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Danoff JR, Goel R, Sutton R, Maltenfort MG, Austin MS. How much pain is significant? Defining the minimal clinically important difference for the visual analog scale for pain after total joint arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2018;33(7 suppl):S71–S75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Dawson J, Fitzpatrick R, Carr A, Murray D. Questionnaire on the perceptions of patients about total hip replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1998;80(1):63–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Department for Work and Pensions. Work, health and disability green paper: data pack. https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/work-health-and-disability-green-paper-data-pack. Published October 31, 2016 Last updated September 1, 2017 Accessed December 29, 2018.

- 12. Duivenvoorden T, Brouwer R, van Raai T, Verhagen A, Verhaar J, Bierma-Zeinstra S. Braces and orthoses for treating osteoarthritis of the knee. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;3:CD004020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hawker GA, Mian S, Kendzerska T, French M. Measures of adult pain: Visual Analog Scale for Pain (VAS Pain), Numeric Rating Scale for Pain (NRS Pain), McGill Pain Questionnaire (MPQ), Short-Form McGill Pain Questionnaire (SF-MPQ), Chronic Pain Grade Scale (CPGS), Short Form-36 Bodily Pain Scale (SF-36 BPS), and Measure of Intermittent and Constant Osteoarthritis Pain (ICOAP). Arthritis Care Res. 2011;63:S240–S252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hjartarson HF, Toksvig-Larsen S. The clinical effect of an unloader brace on patients with osteoarthritis of the knee, a randomized placebo controlled trial with one year follow up. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2018;19(1):341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ingelsrud LH, Roos EM, Terluin B, Gromov K, Husted H, Troelsen A. Minimal important change values for the Oxford Knee Score and the Forgotten Joint Score at 1 year after total knee replacement. Acta Orthop. 2018;89(5):541–547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Irrgang J. Summary of clinical outcome measures for sports-related knee injuries. AOSSM Outcomes Task Force. https://www.sportsmed.org/AOSSMIMIS/members/downloads/research/ClinicalOutcomeMeasuresKnee.pdf. Published June 5, 2012 Accessed December 29, 2018.

- 17. Katz NP, Paillard FC, Ekman E. Determining the clinical importance of treatment benefits for interventions for painful orthopedic conditions. J Orthop Surg Res. 2015;10:24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kellgren JH, Lawrence JS. Radiological assessment of osteo-arthrosis. Ann Rheum Dis. 1957;16:494–502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kocher MS, Steadman JR, Briggs KK, Sterett WI, Hawkins RJ. Reliability, validity, and responsiveness of the Lysholm knee scale for various chondral disorders of the knee. J Bone Joint Surg. 2004;86(6):1139–1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lee PYF, Brock J, Mansoor S, Whiting B. Knee braces and anti-inflammatory sleeves in osteoarthritis, innovation for the 21st century? J Arthritis. 2018;7:e117. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lee PYF, Winfield TG, Harris SRS, Storey E, Chandratreya A. Unloading knee brace is a cost-effective method to bridge and delay surgery in unicompartmental knee arthritis. BMJ Open Sport Exerc Med. 2017;2(1):e000195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lepine J, Briley M. The epidemiology of pain in depression. Hum Psychopharmacol. 2004;19(suppl 1):S3–S7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lützner J, Kasten P, Günther KP, Kirschner S. Surgical options for patients with osteoarthritis of the knee. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2009;5(6):309–316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Mistry DA, Chandratreya A, Lee PYF. An update on unloading knee braces in the treatment of unicompartmental knee osteoarthritis from the last 10 years: a literature review. Surg J (NY). 2018;4(3):e110–e118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Newberry SJ, FitzGerald J, SooHoo NF, et al. Treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee: an update review In: AHRQ Comparative Effectiveness Reviews. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2017; 12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. NICE: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Osteoarthritis: care and management. Section 1.4: nonpharmacological management. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg177/chapter/1-Recommendations#non-pharmacological-management-2. Published February 2014 Accessed December 29, 2018.

- 27. NHS Digital. Provisional quarterly patient reported outcome measures (PROMs) in England, April 2016 to March 2017. http://digital.nhs.uk/catalogue/PUB30192. Published February 8, 2018 Accessed December 29, 2018.

- 28. Royal Society of Chemistry. Germanium. http://www.rsc.org/periodic-table/element/32/germanium. Accessed December 29, 2018.

- 29. Vaishya R, Pariyo GB, Agarwal AK, Vijay V. Non-operative management of osteoarthritis of the knee joint. J Clin Orthop Trauma. 2016;7(3):170–176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Zahiri CA, Schmalzried TP, Szuszczewicz ES, Amstutz HC. Assessing activity in joint replacement patients. J Arthroplasty. 1998;13:890–895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Zhang Y, Jordan JM. Epidemiology of osteoarthritis. Clin Geriatr Med. 2010;26(3):355–369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]