Introduction

Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome (BHDS) is an uncommon genetic disorder affecting the skin, lungs, and kidneys. It is characterized by numerous benign skin tumors (fibrofolliculomas, trichodiscomas, and acrochordons), especially on the face, neck, and chest.1 Although BHDS has a well-known link with malignancy, especially renal cancer, it is infrequently considered in dermatology patients with atypical nevi and melanoma.2 However, increased melanoma risk, including choroidal melanoma, is associated with BHDS.3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9 Here, we report a patient with multiple primary cutaneous melanomas and atypical nevi that triggered evaluation for an underlying genetic cause. We bring this underreported clinical co-occurrence to the attention of dermatologists.

Case report

A 50-year-old woman with Fitzpatrick type 1-2 skin and a history of melanoma and atypical nevi presented for her recommended biannual dermatologic evaluation. Despite adherence to sun protection measures, prior dermatology examinations over 18 years had shown 15 biopsy-proven atypical nevi. Three were severely atypical, and 12 were moderately atypical. Just 4 months earlier, malignant melanoma, superficial spreading type (Breslow thickness of 0.7 mm and immunoreactive for melan A), was diagnosed from the anterior portion of her right forearm. Environmental risk factors included a limited, remote history of tanning bed use over 1 year and sunburns but no outdoor work or immunosuppression. She denied any history of lung or renal disease. On examination, tan-brown nevi of various sizes in a widely scattered distribution and a slightly darker suspicious site on the right back-lateral aspect of the lower leg were noted. Biopsy showed superficial spreading melanoma, Breslow thickness of 0.28 mm, and positive melan A reactivity (Fig 1). This unexpected history of 2 new melanomas over a short period prompted more careful review. Genetics consultation with detailed family history showed paternal renal cysts requiring surgical removal and a brother and son each having dysplastic nevi and singular malignant melanoma at an unknown age and age 21 years, respectively. On skin examination, numerous firm, whitish, dome-shaped papules were noted on her face, chest, and back. Three subtle lesions were biopsied, and 1 histologically confirmed fibrofolliculoma was noted, which meets the criterion for dermatologic diagnosis of this syndrome (Fig 2 and Table I).1 After pretest counseling with a genetics specialist, the patient was offered testing for an FLCN mutation. She declined because of cost and the potential for insurance discrimination.

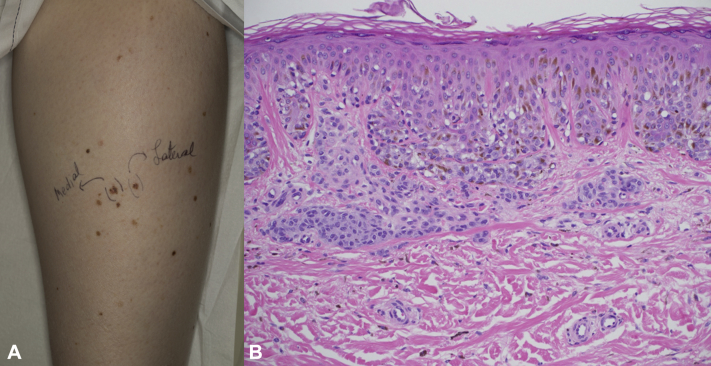

Fig 1.

Melanoma. A, Lower part of the right leg, tibial region. Multiple atypical, pigmented nevi and biopsy-proven melanoma. B, Skin histopathology from right back-lateral leg, tibial area. Melanoma with superficial dermal invasion to 0.28 mm. (Hematoxylin-eosin; original magnification: ×40.)

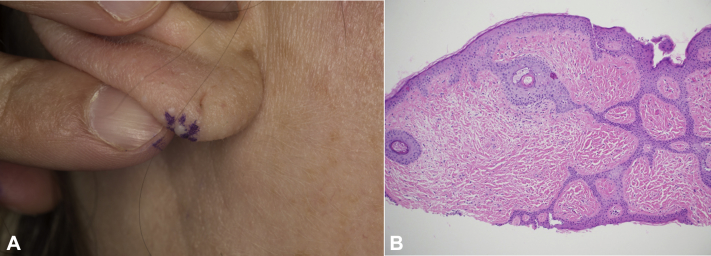

Fig 2.

Fibrofolliculoma. A, Right ear lobe. Representative firm, white, dome-shaped papule. B, Skin histopathology from right ear lobe papule. (Hematoxylin-eosin; original magnification: ×40.)

Table I.

Criteria for diagnosis of Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome

| Major criteria∗ |

|

| Minor criteria∗ |

|

BHDS, Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome.

Patients need to fulfill 1 major criterion or 2 minor criteria for diagnosis. Adapted from Toro.1

Discussion

BHDS is a rare autosomal dominant disorder affecting not only the skin but also the respiratory and renal systems. The clinical presentation varies greatly among affected individuals, even in the same family. Spontaneous pneumothorax due to lung cysts may be one of the earliest manifestations, and up to one third of individuals with BHDS have a lifetime likelihood of developing renal tumors. More than 90% of patients present with benign cutaneous manifestations, which are generally noted in a person's 20s or 30s, and these progressively increase in number and size over time.10 Despite progression, skin features are rarely cosmetically disfiguring and do not come to medical attention. Multiple melanomas and atypical nevi, however, are more likely to draw the attention of a dermatologist, especially when more than 1 melanoma is present in the same patient.

In general, skin cancer risk is considered to be multifactorial, that is, due to a combination of factors such as genetics, environment, and random chance. This patient endorsed some environmental risk factors for melanoma but not others. Her striking history of multiple melanomas despite sun protection suggested a genetic cause and prompted more careful review. Genetic consultation included closer review of family history and physical examination for signs of a genetic cancer syndrome to improve the accuracy of genetic testing or make a diagnosis. This review found multiple, previously unrecognized facial papules suspicious for BHDS.

A literature review for association of BHDS and melanoma showed a case series reporting 8 patients with cutaneous melanoma diagnoses in a cohort of 83 individuals with BHDS. Similar to our case, 1 patient had multiple primary diagnoses of melanoma.8 Interestingly, the rate of melanoma increased from 2.1% in the general population to 10% for patients with BHDS. Table II11, 12, 13 summarizes all reports of cutaneous melanoma in patients with BHDS to date. Further studies are warranted to determine the lifetime risk of melanoma in patients with BHDS and how environmental factors and skin type influence this risk.

Table II.

Patient characteristics in reported cases of cutaneous melanoma diagnosed in BHDS patients

| Study | Study description | Mutational analysis | Dermatologic assessment | Pulmonary involvement | Renal involvement | Others |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sattler et al8 | Multinational European study assessing the prevalence of dysplastic nevi and cutaneous melanoma in a cohort of BHDS families |

|

– >60% female – 62.5% invasive stage I-IV

|

N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Jaster and Wachsmann11 | Case report of a 64-year-old man with BHDS receiving immunosuppression therapy for renal transplantation | N/A | Malignant melanoma | Malignant mesothelioma, epithelial subtype | Polycystic kidney disease | N/A |

| Mota-Burgos et al4 | Case report of a 54-year-old man with BHDS | FLCN mutation present |

|

None | None | Several colorectal tubulovillous adenomas |

| Kasi and Dearmond5 | Case report of a 70-year-old man with BHDS | N/A |

|

Multiple pulmonary cysts | Clear cell renal cell carcinoma and bilateral renal cysts | Colorectal tubulovillous adenoma |

| Cocciolone et al9 | Case report of a 58-year-old man with BHDS | FLCN mutation present |

|

History of spontaneous pneumothorax | None | Salivary gland oncocytoma |

| Welsch et al3 | Case report of a 52-year-old man with BHDS | N/A |

|

Solitary bullae in right lung and history of pneumothorax | Chromophobe-type renal cell carcinoma | Multinodular goiter |

| Toro et al12 | Case series assessing renal findings in 28 BHDS patients | FLCN mutation present in 1 of 2 patients |

– Fibrofolliculomas and/or trichodiscomas |

N/A | Renal oncocytoma and bilateral solid lesions | N/A |

| Khoo et al13 | Case series assessing genetic and clinical findings in 32 BHDS patients | FLCN mutation present |

|

Pneumothorax and lung cancer in some patients | Renal cysts and renal cell carcinoma present in some patients | The following findings were observed in some patients:

|

N/A, Not available.

BHDS is caused by mutations in the tumor suppressor folliculin (FLCN), which is expressed in and is important for the development of skin, lungs, and kidneys.14 Loss of FLCN constitutively activates adenosine monophosphate–activated protein kinase (AMPK), a key enzyme that regulates energy metabolism and melanogenesis.15, 16, 17 Constitutive activation of AMPK leads to autophagy and resistance to many stressors that would normally kill atypical cells. This eventually leads to cellular transformation and, possibly, tumor formation. Autophagy has been strongly linked to the formation of melanoma.18, 19, 20, 21, 22 This is likely the same process responsible for melanoma in patients with BHDS, but further work is warranted in this area.

Because of the subtle presentation of the BHDS lesions, we recommend obtaining a thorough family history in patients with multiple primary melanomas and a careful examination for subtle facial and upper body follicular papules due to the increased possibility of BHDS. In addition, the reverse applies as well. Patients with suspected BHDS should be examined for abnormal or dysplastic moles and potentially melanoma.

Footnotes

Funding sources: None.

Conflicts of interest: None disclosed.

References

- 1.Toro J.R. Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome. In: Adam M.P., Ardinger H.H., Pagon R.A., editors. GeneReviews. University of Washington, Seattle; Seattle, WA: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schmidt L.S., Linehan W.M. FLCN: the causative gene for Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome. Gene. 2018;640:28–42. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2017.09.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Welsch M.J., Krunic A., Medenica M.M. Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome. Int J Dermatol. 2005;44:668–673. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2004.02095.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mota-Burgos A., Acosta E.H., Marquez F.V., Mendiola M., Herrera-Ceballos E. Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome in a patient with melanoma and a novel mutation in the FCLN gene. Int J Dermatol. 2013;52:323–326. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2012.05742.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kasi P.M., Dearmond D.T. Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome: answering questions raised by a case report published in 1962. Case Rep Oncol. 2011;4:363–366. doi: 10.1159/000330446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fontcuberta I.C., Salomao D.R., Quiram P.A., Pulido J.S. Choroidal melanoma and lid fibrofolliculomas in Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome. Ophthalmic Genet. 2011;32:143–146. doi: 10.3109/13816810.2010.544367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marous C.L., Marous M.R., Welch R.J., Shields J.A., Shields C.L. Choroidal melanoma, sector melanocytosis, and retinal pigment epithelial microdetachments in Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome. Retin Cases Brief Rep. 2017;13(3):202–206. doi: 10.1097/ICB.0000000000000595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sattler E.C., Ertl-Wagner B., Pellegrini C. Cutaneous melanoma in Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome: part of the clinical spectrum? Br J Dermatol. 2018;178:e132–e133. doi: 10.1111/bjd.15937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cocciolone R.A., Crotty K.A., Andrews L., Haass N.K., Moloney F.J. Multiple desmoplastic melanomas in Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome and a proposed signaling link between folliculin, the mTOR pathway, and melanoma susceptibility. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:1316–1318. doi: 10.1001/archdermatol.2010.333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Steinlein O.K., Ertl-Wagner B., Ruzicka T., Sattler E.C. Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome: an underdiagnosed genetic tumor syndrome. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2018;16:278–283. doi: 10.1111/ddg.13457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jaster A., Wachsmann J. Serendipitous discovery of peritoneal mesothelioma. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent) 2016;29:185–187. doi: 10.1080/08998280.2016.11929410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Toro J.R., Glenn G., Duray P. Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome: a novel marker of kidney neoplasia. Arch Dermatol. 1999;135:1195–1202. doi: 10.1001/archderm.135.10.1195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Khoo S.K., Giraud S., Kahnoski K. Clinical and genetic studies of Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome. J Med Genet. 2002;39:906–912. doi: 10.1136/jmg.39.12.906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Warren M.B., Torres-Cabala C.A., Turner M.L. Expression of Birt-Hogg-Dubé gene mRNA in normal and neoplastic human tissues. Mod Pathol. 2004;17:998–1011. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bang S., Won K.H., Moon H.R. Novel regulation of melanogenesis by adiponectin via the AMPK/CRTC pathway. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2017;30:553–557. doi: 10.1111/pcmr.12596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yan M., Gingras M.C., Dunlop E.A. The tumor suppressor folliculin regulates AMPK-dependent metabolic transformation. J Clin Invest. 2014;124:2640–2650. doi: 10.1172/JCI71749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Possik E., Jalali Z., Nouët Y. Folliculin regulates AMPK-dependent autophagy and metabolic stress survival. PLOS Genet. 2014;10:e1004273. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pérez L., Sinn A.L., Sandusky G.E., Pollok K.E., Blum J.S. Melanoma LAMP-2C modulates tumor growth and autophagy. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2018;6:101. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2018.00101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ferrarelli L.K. Autophagy-independent p62 in metastatic melanoma. Sci Signal. 2019;12:eaaw8024. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xie X., White E.P., Mehnert J.M. Coordinate autophagy and mTOR pathway inhibition enhances cell death in melanoma. PLoS One. 2013;8:e55096. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0055096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Alonso-Curbelo D., Riveiro-Falkenbach E., Pérez-Guijarro E. RAB7 controls melanoma progression by exploiting a lineage-specific wiring of the endolysosomal pathway. Cancer Cell. 2014;26:61–76. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2014.04.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.García-Fernández M., Karras P., Checinska A. Metastatic risk and resistance to BRAF inhibitors in melanoma defined by selective allelic loss of ATG5. Autophagy. 2016;12:1776–1790. doi: 10.1080/15548627.2016.1199301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]