Abstract

Purpose

Estimate prevalence of types of cancer-related financial hardship by race and test whether they are associated with limiting care due to cost.

Methods

We used data from 994 participants (411 white, 583 African-American) in a hospital-based cohort study of survivors diagnosed with breast, colorectal, lung, or prostate cancer since January 1, 2013. Financial hardship included decreased income, borrowing money, cancer-related debt, and accessing assets to pay for cancer care. Limiting care included skipping doses of prescribed medication, refusing treatment, or not seeing a doctor when needed due to cost. Logistic regression models controlled for sociodemographic factors.

Results

More African American than white survivors reported financial hardship (50.3% vs. 41.0%, p=0.005) and limiting care (20.0% vs. 14.2%, p=0.019). More white than African American survivors reported utilizing assets (9.3% vs. 4.8%, p=0.006), while more African American survivors reported cancer-related debt (30.5% vs. 18.5%, p<0.001). Survivors who experienced financial hardship were 4.4 (95% CI: 2.9, 6.6) times as likely to limit care as those who did not. Borrowing money, cancer-related debt, and decreased income were each independently associated with limiting care, while accessing assets was not.

Conclusions

The prevalence of some forms of financial hardship differed by race, and these were differentially associated with limiting care due to cost.

Implications for Cancer Survivors

The ability to use assets to pay for cancer care may protect survivors from limiting care due to cost. This has differential impacts on white and African American survivors.

Keywords: African American, cancer, disparities, financial hardship, limiting care, race

INTRODUCTION

Nearly half of cancer survivors in the United States report some form of financial hardship related to cancer.[1] Previous work has identified three broad domains of financial hardship, including material, behavioral, and psychological.[1] Material financial hardship (referred to as “financial hardship” throughout this manuscript) can take many forms, including using savings to pay for cancer care,[2] the inability to cover medical and household bills,[3] and experiencing high levels of debt or filing for bankruptcy,[4]–[8] even among survivors with health insurance.[5], [6] Financial hardship due to cancer has been associated with poorer access to medical care,[7], [8] which can lead to poor quality of life[9], [10] and even mortality.[11]

One way that patients may cope with financial hardship related to cancer is to limit the medical care they receive (behavioral financial hardship [1]). This may include delaying treatment or not seeing healthcare providers when necessary, taking less than the prescribed amount of medications, and refusing treatments.[1], [12] Cancer survivors are more likely than adults with no history of cancer to forgo several types of care, including medical, dental, and mental health care and prescription medications,[7] Financial problems are associated with forgoing cancer care due to cost,[8], [13] specifically, high out-of-pocket costs and other financial strains are associated with nonadherence to prescription medications among cancer patients and survivors,[13]–[16] and with not receiving recommended surveillance after a cancer diagnosis.[17]

There is evidence that financial hardship is most common among racial/ethnic minority and low-income survivors;[3], [8], [18]–[21] however, less is known about whether the types of financial hardship experienced differ by race.[3], [22] Additionally, previous work has not established whether the association between financial hardship and limiting care due to cost varies by type of financial hardship. Different forms of financial hardship may have different implications for decisions around accessing care. Specifically, needing to borrow money or take on cancer-related debt may have different implications for limiting care than being able to pay for necessary treatment using existing financial resources.

The purpose of this study is twofold: 1) to estimate the prevalence of both material financial hardship and limiting care due to cost (behavioral financial hardship) and test whether the prevalence of each type of financial hardship and care limitation differs by race, and 2) to estimate the association between total and specific types of financial hardship and limiting care due to cost. We hypothesize that the types of financial hardship experienced will differ by race, and that all forms of financial hardship will be associated with limiting care due to cost.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Study Cohort

The Detroit Research on Cancer Survivors (Detroit ROCS) pilot is a hospital-based, prospective cohort study designed to investigate the associations between comorbid conditions, medical history, health behaviors, social support, financial well-being, and health-related outcomes among African-American and white cancer survivors.[23] Participants were eligible to join the cohort if they were between the ages of 20 and 79; diagnosed with a primary, invasive colorectal, lung, prostate or female breast cancer on or after January 1, 2013, and diagnosed and/or treated at the Karmanos Cancer Center (KCC) in Detroit, Michigan.

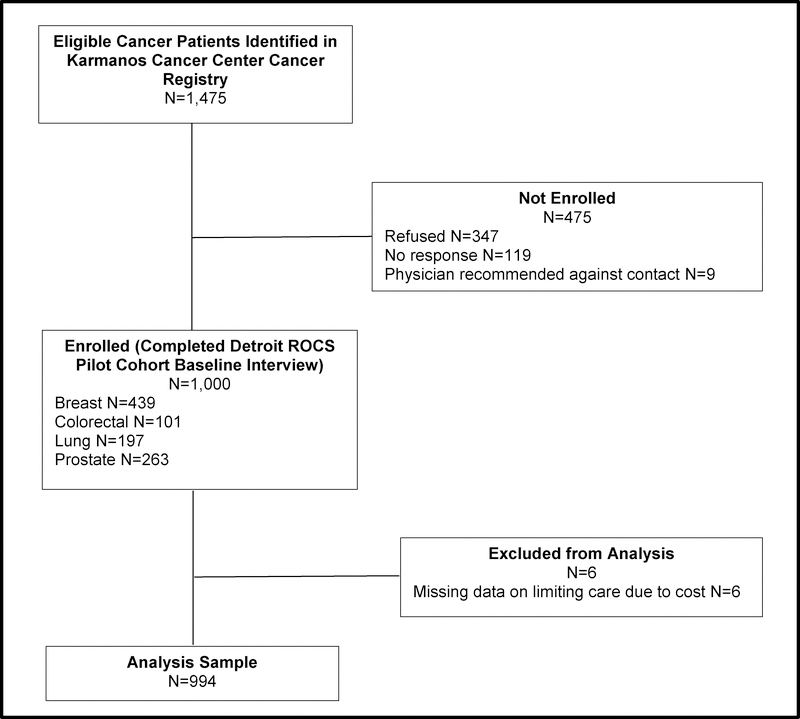

A flow diagram of participant recruitment appears in Figure 1. Data queries of the KCC cancer registry between September, 2015 and January, 2016 identified 1,475 potentially eligible participants. We contacted the physician of record for each asking if they objected to the patient being invited to participate. We sent participant invitation letters if we did not receive a physician objection within three weeks. Nine survivors were excluded due to physician objection, 347 refused, and 119 did not respond to repeated invitations, for a total of 1,000 survivors enrolled into the cohort (response rate=67.8%). Response rates were higher in African American (69.6%) than white survivors (65.4%) and in breast (70.2%) and lung (70.6%) cancer survivors compared with survivors of colorectal (66.4%) and prostate (62.8%) cancer. Response rates did not differ by stage (67.7% among local/regional disease vs. 68.2% for distant stage disease) or time since diagnosis (67.8% within 15 months of diagnosis and 15+ months since diagnosis). Participants completed baseline surveys online using Qualtrics (30.3%) or over the phone with a trained interviewer (69.7%) between March 2015 and June 2017. Analyses exclude participants missing information on all measures of limiting care due to cost (N=6), for an analytic sample of 994 participants. Included participants had complete data for all measures of financial hardship.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of study sample

Data Collection

Participant demographic and socioeconomic characteristics including race, sex, income, education, marital status, employment, and cancer treatments received were self-reported using categories included in Table 1 and reflect information at the time of survey completion rather than at cancer diagnosis unless otherwise noted. Health insurance information regarding private insurance, Medicare, and Medicaid coverage is from self-reported responses to the question, “What kind of health insurance do you currently have?” with response options of Medicare only, Medicare plus other insurance, private insurance through an employer, private insurance not through an employer, Veterans Affairs, Medicaid, no insurance, and other. Information related to experiencing financial hardship and limiting care due to cost were also self-reported using previously-developed measures, as described below.[20], [24] Age at diagnosis and additional cancer-related information including site, stage, and time since diagnosis were obtained through linkage with the Metropolitan Detroit Cancer Surveillance System.

Table 1.

Descriptive characteristics of cohort participants

| Total | White | African American | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N=994 | N=411 | N=583 | ||||

| Characteristic | N | % | N | % | N | % |

| Race | ||||||

| African American | 583 | 58.7 | 583 | 100 | -- | -- |

| White | 411 | 41.4 | -- | -- | 411 | 100 |

| Sex | ||||||

| Female | 615 | 61.9 | 260 | 63.3 | 355 | 60.9 |

| Male | 379 | 38.1 | 151 | 36.7 | 228 | 39.1 |

| Age at diagnosis | ||||||

| <55 | 265 | 2637 | 121 | 29.4 | 144 | 24.7 |

| 55–59 | 218 | 21.9 | 70 | 17.0 | 148 | 25.4 |

| 60–64 | 207 | 20.8 | 77 | 18.7 | 130 | 22.3 |

| 65+ | 304 | 30.6 | 143 | 34.8 | 161 | 27.6 |

| Income | ||||||

| <$20,000 | 395 | 42.4 | 58 | 15.3 | 337 | 60.9 |

| $20,000–39,999 | 169 | 18.1 | 68 | 17.9 | 101 | 18.3 |

| $40,000–59,999 | 114 | 12.2 | 61 | 16.1 | 53 | 9.6 |

| $60,000–79,999 | 69 | 7.4 | 37 | 9.8 | 32 | 5.8 |

| $80,000+ | 185 | 19.9 | 155 | 40.9 | 30 | 5.42 |

| Education | ||||||

| Less than high school | 115 | 11.7 | 24 | 5.8 | 91 | 15.8 |

| High school/GED | 297 | 30.1 | 97 | 23.6 | 200 | 34.7 |

| Some college | 345 | 35.0 | 134 | 32.6 | 211 | 36.6 |

| College degree | 230 | 23.3 | 156 | 38.0 | 74 | 13.0 |

| Marital status | ||||||

| Married/living with partner | 457 | 46.3 | 298 | 73.0 | 159 | 27.5 |

| Widowed | 108 | 10.9 | 28 | 6.9 | 80 | 13.8 |

| Divorced/separated | 227 | 23.0 | 60 | 14.7 | 167 | 28.8 |

| Never married | 195 | 19.8 | 22 | 5.4 | 173 | 29.9 |

| Employment status | ||||||

| Employed full time | 197 | 19.8 | 120 | 29.2 | 77 | 13.2 |

| Employed part time | 80 | 8.1 | 49 | 11.9 | 31 | 5.3 |

| Homemaker | 37 | 3.7 | 17 | 4.1 | 20 | 3.4 |

| Unemployed | 86 | 8.7 | 22 | 5.4 | 64 | 11.0 |

| Retired | 360 | 36.2 | 152 | 37.0 | 208 | 35.7 |

| Medical leave/disability | 221 | 22.2 | 48 | 11.7 | 173 | 29.7 |

| Other/missing | 13 | 1.3 | 3 | 0.7 | 10 | 1.7 |

| Any private health insurance | ||||||

| No | 302 | 30.8 | 56 | 13.8 | 246 | 42.7 |

| Yes | 680 | 69.3 | 350 | 86.2 | 330 | 57.3 |

| Any Medicare | ||||||

| No | 552 | 56.0 | 239 | 58.6 | 313 | 54.3 |

| Yes | 433 | 44.0 | 169 | 41.4 | 264 | 45.8 |

| Any Medicaid | ||||||

| No | 771 | 78.5 | 367 | 90.4 | 404 | 70.1 |

| Yes | 211 | 21.5 | 39 | 9.6 | 172 | 29.9 |

| Cancer site | ||||||

| Breast | 439 | 44.2 | 174 | 42.3 | 265 | 45.5 |

| Colorectal | 101 | 10.2 | 51 | 12.4 | 50 | 8.6 |

| Lung | 194 | 19.5 | 100 | 24.3 | 94 | 16.1 |

| Prostate | 260 | 26.2 | 86 | 20.9 | 174 | 29.9 |

| Cancer stage at diagnosis | ||||||

| I | 286 | 28.9 | 112 | 27.5 | 174 | 29.9 |

| II | 337 | 34.0 | 120 | 29.4 | 217 | 37.3 |

| III | 190 | 19.2 | 83 | 20.3 | 107 | 18.4 |

| IV | 177 | 17.9 | 93 | 22.8 | 84 | 14.4 |

| Cancer treatments | ||||||

| Surgery | ||||||

| Yes | 696 | 70.3 | 294 | 71.5 | 402 | 69.4 |

| No | 294 | 29.7 | 117 | 28.5 | 177 | 30.6 |

| Chemotherapy | ||||||

| Yes | 535 | 54.2 | 235 | 57.6 | 300 | 51.8 |

| No | 452 | 45.8 | 173 | 42.4 | 279 | 48.2 |

| Radiation | ||||||

| Yes | 601 | 61.2 | 232 | 57.7 | 369 | 63.6 |

| No | 381 | 38.8 | 170 | 42.3 | 211 | 36.4 |

| Time since diagnosis | ||||||

| <12 months | 161 | 16.2 | 76 | 18.5 | 85 | 14.6 |

| 12–17 months | 352 | 35.5 | 129 | 31.4 | 223 | 38.3 |

| 18–23 months | 228 | 23.0 | 97 | 23.6 | 131 | 22.5 |

| 24+ months | 252 | 25.4 | 109 | 26.5 | 143 | 24.6 |

Financial Hardship

Participants were asked whether, in order to pay bills related to their cancer treatment, they had to do any of the following, and were instructed to select all that apply: 1) refinance or take out a second mortgage on their home, 2) sell their home, 3) sell stocks or other investments, or 4) withdraw money from retirement accounts. Selected items were coded as ‘yes’ and items left blank were coded as ‘no’. They were separately asked whether their income had declined since their cancer diagnosis; whether they or any member of their family had to borrow money from friends or other family members to help pay for their cancer treatment; and/or whether they were currently in debt due to expenses related to their cancer. Participants were considered to have experienced financial hardship if they answered in the affirmative to any of the above items. In sub-analyses, measures of having to borrow money, currently being in cancer-related debt, and experiencing a decrease in income were each considered separately. Participants were counted as accessing assets if they indicated that they refinanced or sold their home, sold stocks or other investments, or withdrew money from retirement accounts to pay for cancer care. All of the financial hardship questions are from previous work by Shankaran, et al.[20]

Limiting care due to cost

Three items assessed whether participants limited care related to their cancer diagnosis due to cost: (1) “Was there a time in the past 12 months when you needed to see a doctor but could not because of cost?”; (2) “Did you ever turn down treatments (chemotherapy, radiation, pain medications, anti-nausea medications, anti-diarrhea medications, or other recommended cancer treatments) because you were concerned about the cost?”; and (3) “Did you ever skip doses of a prescribed medication to save money?”. The first question is from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System[24] and the others are based on previous work by Shankaran, et al.[20] Participants were considered to have limited care due to cost if they answered in the affirmative to any of these items.

Statistical Analysis

Odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) of the associations between any and specific types of financial hardship and limiting care due to cost were estimated using logistic regression models. We present results of models controlling only for age at diagnosis and sex, and models additionally controlling for income, employment status, marital status, health insurance, and cancer site, all using the categories presented in Table 1. These factors were included a priori based on previous literature describing predictors of financial hardship among cancer survivors. We further considered education, time since diagnosis, and cancer treatments received as additional covariates, but none were associated with limiting care due to cost in adjusted models and none changed the overall observed association between financial hardship and limiting care, so they were excluded from our analyses.

Finally, models of individual types of financial hardship were also mutually adjusted for each of the other forms of financial hardship (e.g., the model of the association between borrowing money and limiting care due to cost controls for debt, utilizing assets, and reporting a decrease in income).

In sensitivity analyses we assessed whether differences in types of financial hardship by race remained after controlling for household income. We further assessed whether observed associations between financial hardship and limiting care differed by race by fitting adjusted models separately among white and African American survivors. A test for interaction was conducted by including an interaction term (financial hardship x race) in the model of any financial hardship and limiting care due to cost. We used the same procedure to test for interaction by time since diagnosis split at the median of 18 months. All statistical tests were two-sided. Analyses were conducted using Stata 14.0 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX).

RESULTS

A majority of participants were women (61.9%), younger than 65 at diagnosis (69%), and African-American (58.7%) (Table 1). More than 40% of participants reported incomes below $20,000 per year. Approximately one-quarter (27.9%) were employed full or part time at baseline. A majority (69.3%) reported having some form of private health insurance coverage, either on its own or in combination with other coverage, while 44% were enrolled in Medicare and 21.5% were enrolled in Medicaid. The most common cancer in the cohort was breast (44.2%), followed by prostate (26.2%), lung (19.5%), and colorectal (10.2%).

Table 2 gives the prevalence of financial hardship and limiting care due to cost by participant sociodemographic and cancer-related characteristics. Nearly half of participants (46.4%) reported experiencing any financial hardship associated with cancer, and 17.6% limited care due to cost. Financial hardship was more common among women, younger survivors, those from lower income households, those who were not married or living with a partner. Financial hardship also varied by employment, marital status, and health insurance coverage, and was most common among breast cancer survivors, those diagnosed with late-stage disease, and those who received any chemotherapy. Predictors of limiting care due to cost included younger age, being unmarried, being unemployed or on disability, and having Medicaid coverage

Table 2.

Material financial hardship and limiting care due to cost by participant sociodemographic and cancer-related characteristics

| Any Financial Hardship | Any Limiting Care Due to Cost | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | P | N | % | P | |

| Total | 436 | 46.4 | 171 | 17.6 | ||

| Sex | ||||||

| Female | 291 | 50.6 | 0.001 | 108 | 17.9 | 0.786 |

| Male | 145 | 39.8 | 63 | 17.2 | ||

| Age at diagnosis | ||||||

| <55 | 146 | 57.0 | <0.001 | 49 | 19.1 | 0.111 |

| 55–59 | 109 | 51.4 | 44 | 20.4 | ||

| 60–64 | 93 | 48.4 | 39 | 19.2 | ||

| 65+ | 88 | 31.5 | 39 | 13.1 | ||

| Income | ||||||

| <$20,000 | 201 | 53.6 | <0.001 | 103 | 26.6 | <0.001 |

| $20,000–39,999 | 81 | 50.0 | 29 | 17.7 | ||

| $40,000–59,999 | 45 | 41.7 | 14 | 12.5 | ||

| $60,000–79,999 | 33 | 49.3 | 9 | 13.2 | ||

| $80,000+ | 53 | 30.8 | 10 | 5.5 | ||

| Education | ||||||

| Less than high school | 41 | 38.7 | 0.007 | 23 | 20.7 | 0.27 |

| High school/GED | 138 | 48.6 | 57 | 19.8 | ||

| Some college | 169 | 52.0 | 56 | 16.5 | ||

| College degree | 85 | 39.0 | 32 | 14.1 | ||

| Marital status | ||||||

| Married/living with partner | 171 | 39.1 | <0.001 | 54 | 12.1 | <0.001 |

| Widowed | 51 | 51.5 | 29 | 27.4 | ||

| Divorced/separated | 109 | 52.4 | 46 | 21.0 | ||

| Never married | 102 | 54.3 | 40 | 20.8 | ||

| Employment status | ||||||

| Employed full time | 85 | 45.0 | 0.001 | 23 | 11.8 | 0.023 |

| Employed part time | 39 | 52.7 | 16 | 20.0 | ||

| Homemaker | 12 | 37.5 | 6 | 17.1 | ||

| Unemployed | 52 | 61.9 | 21 | 24.4 | ||

| Retired | 129 | 38.5 | 52 | 15.0 | ||

| Other/missing | 6 | 50.0 | 2 | 15.4 | ||

| Medical leave/disability | 113 | 53.1 | 51 | 23.6 | ||

| Any private health insurance | ||||||

| No | 163 | 56.6 | <0.001 | 71 | 24.2 | <0.001 |

| Yes | 268 | 41.7 | 98 | 14.7 | ||

| Any Medicare | ||||||

| No | 272 | 51.6 | <0.001 | 96 | 17.9 | 0.76 |

| Yes | 159 | 39.4 | 73 | 17.1 | ||

| Any Medicaid | ||||||

| No | 318 | 43.6 | 0.002 | 118 | 15.6 | 0.002 |

| Yes | 113 | 56.2 | 51 | 24.8 | ||

| Cancer site | ||||||

| Breast | 211 | 51.2 | 0.016 | 81 | 18.6 | 0.72 |

| Colorectal | 45 | 46.4 | 13 | 13.7 | ||

| Lung | 84 | 46.7 | 32 | 17.1 | ||

| Prostate | 96 | 38.4 | 45 | 17.7 | ||

| Cancer stage at diagnosis | ||||||

| I | 88 | 33.5 | <0.001 | 46 | 16.3 | 0.63 |

| II | 153 | 47.7 | 57 | 17.2 | ||

| III | 99 | 54.7 | 38 | 20.9 | ||

| IV | 95 | 55.9 | 30 | 17.5 | ||

| Cancer treatments | ||||||

| Surgery | ||||||

| Yes | 306 | 46.5 | 0.85 | 121 | 17.7 | 0.95 |

| No | 127 | 45.9 | 50 | 17.5 | ||

| Chemotherapy | ||||||

| Yes | 281 | 54.9 | <0.001 | 101 | 19.4 | 0.11 |

| No | 152 | 36.1 | 69 | 15.5 | ||

| Radiation | ||||||

| Yes | 278 | 41.8 | 0.032 | 104 | 17.6 | 0.82 |

| No | 151 | 49.0 | 63 | 17.0 | ||

| Time since diagnosis | ||||||

| <12 months | 69 | 45.4 | 0.82 | 27 | 17.3 | 0.71 |

| 12–17 months | 157 | 47.0 | 55 | 15.9 | ||

| 18–23 months | 105 | 48.4 | 39 | 17.8 | ||

| 24+ months | 104 | 44.3 | 49 | 19.6 | ||

Financial hardship was more common in African American (50.3%) than white survivors (41.0%, p=0.005) (Table 3). Experiencing a decrease in income was the most common form of financial hardship (29.5%), followed by still being in cancer-related debt (25.5%), borrowing money from family or friends (9.7%), and utilizing assets to pay for cancer care (6.6%).

Table 3.

Prevalence of financial hardship and limiting care due to cost by race

| Total | White | African American | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N=994 | N=411 | N=583 | |||||

| N | % | N | % | N | % | Pa | |

| Any financial hardship | 436 | 46.4 | 159 | 41.0 | 277 | 50.3 | 0.005 |

| Borrowed money from family or friends | 95 | 9.7 | 39 | 9.7 | 56 | 9.7 | 0.98 |

| Remaining debt | 250 | 25.5 | 75 | 18.5 | 175 | 30.5 | <0.001 |

| Utilized assets to pay for cancer care | 66 | 6.6 | 38 | 9.3 | 28 | 4.8 | 0.006 |

| Refinanced or sold home | 9 | 0.9 | 7 | 1.7 | 2 | 0.3 | 0.026 |

| Sold stock or other investments | 15 | 1.5 | 8 | 2.0 | 7 | 1.2 | 0.34 |

| Withdrew money from retirement | 56 | 5.6 | 31 | 7.5 | 25 | 4.3 | 0.028 |

| Experienced a decrease in income | 276 | 29.5 | 110 | 28.2 | 166 | 30.4 | 0.47 |

| Any care limitations | 171 | 17.6 | 57 | 14.2 | 114 | 20.0 | 0.019 |

| Skipped doses of prescribed medication | 71 | 7.2 | 23 | 5.6 | 48 | 8.3 | 0.11 |

| Refused recommended treatment due to cost | 49 | 5.0 | 21 | 5.1 | 28 | 4.8 | 0.83 |

| Needed to see a doctor but did not go due to cost | 111 | 11.4 | 33 | 8.2 | 78 | 13.6 | 0.008 |

Note: Responses are not mutually exclusive.

P-values reflect two-sided Wald test of differences in prevalence of financial hardship or care limitation by race.

The prevalence of some types of financial hardship differed by race (Table 3). More African American (30.5%) than white (18.5%) survivors reported currently being in debt due to cancer (p<0.001), while more white (9.3%) than African American (4.8%) survivors reported utilizing assets to pay for cancer care (p=0.006). These differences were evident for refinancing or selling a home (1.7% of white vs. 0.3% of African American survivors; p=0.026) and withdrawing money from retirement savings to pay for cancer care (7.5% of white vs. 4.3% of African American survivors; p=0.028).

The most common form of limiting care due to cost was needing to see a doctor but not going due to cost (11.4%), followed by skipping doses of prescribed medication to save money (7.2%), and refusing recommended treatment due to cost (5%) (Table 3). More African American (20%) than white (14.2%) survivors reported limiting care due to cost (p=0.019), driven by a higher proportion reporting that they needed to see a doctor but did not go due to cost (13.6% vs. 8.2%; p=0.008).

Table 4 presents odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) for the associations between any financial hardship and limiting care due to cost. In fully adjusted models, participants who experienced any financial hardship were 4.4 (95% CI: 2.6, 6.6) times as likely to report limiting care as those who did not. Financial hardship was associated with skipping doses of prescribed medication (OR: 2.7, 95% CI: 1.5, 4.9), refusing treatment (OR: 5.9, 95% CI: 2.6, 13.7), and needing to see a doctor but not going due to cost (OR: 4.1, 95% CI: 2.4, 6.9). In a mutually adjusted model, borrowing money (OR: 4.0, 95% CI: 2.2, 7.1), debt (OR: 2.9, 95% CI: 1.9, 4.6), and experiencing a decrease in income (OR: 1.7, 95% CI: 1.1, 2.7) remained independently associated with limiting care; however, utilizing assets was no longer associated with limiting care when controlling for the other forms of financial hardship.

Table 4.

Odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) of the association between overall and types of financial hardship and limiting care due to cost

| Age and Sex Adjusted | Fully Adjusted | Mutually Adjusted | |

|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | |

| Any financial hardship | |||

| Any care limitations | 5.0 (3.4, 7.4) | 4.4 (2.9, 6.6) | -- |

| Skipped doses of prescribed medication to save money | 3.2 (1.9, 5.4) | 2.7 (1.5, 4.9) | -- |

| Refused treatment due to cost | 7.5 (3.3, 16.9) | 5.9 (2.6, 13.7) | -- |

| Needed to see a doctor but did not go due to cost | 5.4 (3.3, 8.8) | 4.1 (2.4, 6.9) | -- |

| Borrowed money from friends or family to pay for cancer care | |||

| Any care limitations | 8.1 (5.1, 12.6) | 7.6 (4.6, 12.6) | 3.9 (2.2, 6.9) |

| Reported still being in debt due to cancer | |||

| Any care limitations | 6.2 (4.3, 8.8) | 4.9 (3.4, 7.2) | 3.0 (1.9, 4.6) |

| Used assets (investments, home equity, retirement savings) | |||

| Any care limitations | 2.0 (1.4, 3.0) | 2.2 (1.4, 3.5) | 1.1 (0.6, 1.9) |

| Experienced a decrease in income | |||

| Any care limitations | 2.8 (2.0, 4.0) | 2.7 (1.8, 4.0) | 1.8 (1.1,2.6) |

Fully Adjusted models control for age at diagnosis, sex, income, employment status, marital status, health insurance, and cancer site using categories in Table 1. Mutually Adjusted models add the other forms of financial hardship (borrowing, debt, assets, and/or reduction in income), as appropriate (e.g. models of the associations between borrowing money and care limitations are further adjusted for debt, assets, and decrease in income).

In sensitivity analyses we observed no significant (p<0.05) difference in the types of financial hardship experienced by race or in the association between overall or individual types of financial hardship and care limitations by race or by time since diagnosis split at the median of 18 months (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

Financial hardship was common in this diverse cohort of cancer survivors, and the prevalence of some forms of financial hardship differed by race, with more African-American survivors reporting lasting cancer-related debt and more white survivors reporting utilizing assets to pay for cancer care. Financial hardship was strongly associated with limiting care due to cost, and borrowing money from friends or family and remaining in debt due to cancer remained strongly associated with limiting care even after adjusting for other forms of financial hardship.

Our finding that experiencing financial hardship is associated with limiting care due to cost is consistent with previous findings that financial problems were associated with forgoing or delaying medical care,[8] and especially with nonadherence to prescription medications,[13] including oral oncolytics.[13]–[16]

While several previous studies have reported higher prevalence of financial hardship among non-white compared with white cancer survivors,[3], [8], [18], [20], [21] less is known about how specific types of financial hardship differ by race. Similar to our findings, in a longitudinal study of breast cancer survivors, Jagsi et al. reported that more white (90%) than African American (81%; p<0.001) survivors used income and/or savings to pay for cancer care, while more African American (15%) than white (9%; p=0.03) survivors faced cancer-related debt.[3]

Our finding that the types of financial hardship experienced differed by race, is not surprising given estimates that the median net worth of white adults is approximately thirteen times that of black adults in the United States.[25] This disparity in net worth means that, on average, white adults may be better able to absorb a financial shock such as a cancer diagnosis by accessing assets to avoid cancer-related debt than African Americans.

A recent manuscript by Wheeler, et al.[22] reported that, compared with white women, greater proportions of black breast cancer survivors experienced income loss, financial barriers, transportation barriers, job loss, and insurance loss related to breast cancer. Associations between race and income loss and transportation barriers remained even after controlling for socioeconomic status; however, race was no longer associated with other forms of hardship after controlling for socioeconomic factors. In sensitivity analyses controlling for household income, we no longer observed a difference in prevalence of individual forms of financial hardship or limiting care by race (data not shown). However, the purpose of these analyses is to reflect the reality faced by diverse cancer survivors in the context of race-based differences in socioeconomic status, rather than to propose that the association between race and financial hardship is causal or exists independent of socioeconomic factors.

Importantly, our results further suggest that the types of financial hardship that differed by race were also differentially associated with limiting care due to cost. While utilizing assets to pay for cancer care was more common among white survivors, it was not associated with limiting care due to cost independent of other forms of financial hardship. On the other hand, cancer-related debt, which was more common in African American survivors, was strongly associated with all forms of limiting care due to cost even after accounting for other forms of financial hardship. This may suggest that patients with assets are able to utilize them to avoid limiting care due to cost, while those who go into debt to pay for cancer care also limit care due to cost concerns.

Although the number of uninsured Americans has decreased by 20.2 million after the enactment of Affordable Care Act (ACA) in 2010, approximately 24.4 million adults ages 18–64 years were uninsured in early 2016,[26] and others remained underinsured due to high cost-sharing requirements.[27] Additionally, it is uncertain whether individuals will be able to purchase health coverage that will effectively cover the costs of cancer care in the future. Changes to the coverage available through the ACA, Medicare, and/or Medicaid that result in higher enrollee costs and/or limits to the types of services covered are likely to expose cancer patients to greater financial hardship. This could impact survivors’ ability to access to cancer-related care, particularly for survivors who are not able to use assets to pay for care, and could both negatively impact cancer outcomes and widen the racial disparities in those outcomes in the future.

Limitations of this work should be noted. The measures of financial hardship and care limitations included here have been used in previous work,[20] but are self-reported and have not been validated against survivors’ financial records. Additionally, information about participants’ assets is not available. A participant who indicated they did not use assets to pay for care could have either had the asset but not needed to use it, or not had the asset available. The hospital-based design of this cohort may limit the generalizability of our results. KCC is in the City of Detroit, and acts as a community cancer hospital for the city’s large African American population; however, many of the hospital’s white patients travel from surrounding areas to be treated at a Comprehensive Cancer Center. These patients may have additional resources and/or represent more complex cancer cases than other patients in the metropolitan area. Differences between participants in this cohort and the broader population of cancer survivors are unlikely to bias the strong associations observed here between experiencing financial hardship and limiting care due to cost.

Strengths of this study include the large number of African-American and low-income survivors enrolled, allowing for an examination of the association between financial hardship and forgoing care in populations that are often underrepresented, as well as enabling assessment of the associations between individual types of financial hardship and care limitations. The robustness of the available data allowed us to control for several important demographic, socioeconomic, and cancer-related variables.

Our findings suggest that borrowing and going into debt to pay for cancer care are both strongly associated with limiting care due to cost, independent of other forms of financial hardship. As the literature describing the financial consequences of cancer develops, emphasis is being placed on going beyond describing patterns and moving to intervene to prevent adverse outcomes related to financial hardship.[28] Patients who borrow money or take on cancer-related debt in order to pay for care may represent a priority group to target with interventions to reduce the number of patients who limit care due to cost. This can have implications for providers and hospitals interested in developing and implementing such interventions in their patient populations, and may also have policy implications by motivating continued efforts to ensure that cancer patients with limited financial resources can access recommended care.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This research was funded by the American Cancer Society (MRSG-17-019), NIH grants/contracts PC35145 and HHSN261261201300011I, and by the Karmanos Cancer Institute and the General Motors Foundation.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Ethical Approval: All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments.

Informed Consent: Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in this study.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This Author Accepted Manuscript is a PDF file of a an unedited peer-reviewed manuscript that has been accepted for publication but has not been copyedited or corrected. The official version of record that is published in the journal is kept up to date and so may therefore differ from this version.

References

- [1].Altice CK, Banegas MP, Tucker-Seeley RD, and Yabroff KR, “Financial Hardships Experienced by Cancer Survivors: A Systematic Review,” J. Natl. Cancer Inst, vol. 109, no. 2, p. djw205, February 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Huntington SF et al. , “Financial toxicity in insured patients with multiple myeloma: a cross-sectional pilot study,” Lancet Haematol, vol. 2, no. 10, pp. e408–e416, October 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Jagsi R et al. , “Long-Term Financial Burden of Breast Cancer: Experiences of a Diverse Cohort of Survivors Identified Through Population-Based Registries,” J. Clin. Oncol, p. JCO.2013.53.0956, March 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Chino F et al. , “Self-Reported Financial Burden and Satisfaction With Care Among Patients With Cancer,” The Oncologist, vol. 19, no. 4, pp. 414–420, April 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Yabroff KR, Lund J, Kepka D, and Mariotto A, “Economic Burden of Cancer in the United States: Estimates, Projections, and Future Research,” Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev, vol. 20, no. 10, pp. 2006–2014, October 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Nekhlyudov L, Walker R, Ziebell R, Rabin B, Nutt S, and Chubak J, “Cancer survivors’ experiences with insurance, finances, and employment: results from a multisite study,” J. Cancer Surviv, vol. 10, no. 6, pp. 1104–1111, December 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Weaver KE, Rowland JH, Bellizzi KM, and Aziz NM, “Forgoing medical care because of cost,” Cancer, vol. 116, no. 14, pp. 3493–3504, July 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Kent EE et al. , “Are survivors who report cancer-related financial problems more likely to forgo or delay medical care?,” Cancer, vol. 119, no. 20, pp. 3710–3717, October 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Zafar SY, McNeil RB, Thomas CM, Lathan CS, Ayanian JZ, and Provenzale D, “Population-Based Assessment of Cancer Survivors’ Financial Burden and Quality of Life: A Prospective Cohort Study,” J. Oncol. Pract, vol. 11, no. 2, pp. 145–150, March 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Meneses K, Azuero A, Hassey L, McNees P, and Pisu M, “Does economic burden influence quality of life in breast cancer survivors?,” Gynecol. Oncol, vol. 124, pp. 437–443, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Ramsey SD et al. , “Financial Insolvency as a Risk Factor for Early Mortality Among Patients With Cancer,” J. Clin. Oncol, vol. 34, no. 9, pp. 980–986, March 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Nipp RD et al. , “Identifying cancer patients who alter care or lifestyle due to treatment-related financial distress,” Psychooncology, p. n/a–n/a, July 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Bestvina CM et al. , “Patient-Oncologist Cost Communication, Financial Distress, and Medication Adherence,” J. Oncol. Pract, vol. 10, no. 3, pp. 162–167, May 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Zheng Z et al. , “Do cancer survivors change their prescription drug use for financial reasons? Findings from a nationally representative sample in the United States,” Cancer, p. n/a–n/a, February 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Streeter SB, Schwartzberg L, Husain N, and Johnsrud M, “Patient and Plan Characteristics Affecting Abandonment of Oral Oncolytic Prescriptions,” J. Oncol. Pract, vol. 7, no. 3S, pp. 46s–51s, May 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Kaisaeng N, Harpe SE, and Carroll NV, “Out-of-Pocket Costs and Oral Cancer Medication Discontinuation in the Elderly,” J. Manag. Care Pharm, vol. 20, no. 7, pp. 669–675, July 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].McDougall JA, Banegas MP, Wiggins CL, Chiu VK, Rajput A, and Kinney AY, “Rural Disparities in Treatment-Related Financial Hardship and Adherence to Surveillance Colonoscopy in Diverse Colorectal Cancer Survivors,” Cancer Epidemiol. Prev. Biomark, p. cebp.1083.2017, January 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Pisu M et al. , “Economic hardship of minority and non-minority cancer survivors 1 year after diagnosis: Another long-term effect of cancer?,” Cancer, vol. 121, no. 8, pp. 1257–1264, April 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Arozullah AM et al. , “The Financial Burden of Cancer: Estimates From a Study of Insured Women with Breast Cancer,” J Support Oncol, vol. 2, pp. 271–278, 2004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Shankaran V, Jolly S, Blough D, and Ramsey SD, “Risk Factors for Financial Hardship in Patients Receiving Adjuvant Chemotherapy for Colon Cancer: A Population-Based Exploratory Analysis,” J. Clin. Oncol, vol. 30, no. 14, pp. 1608–1614, May 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Hastert TA et al. , “Financial burden among older, long-term cancer survivors: Results from the LILAC study,” Cancer Med, vol. 0, no. 0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Wheeler SB, Spencer JC, Pinheiro LC, Carey LA, Olshan AF, and Reeder-Hayes KE, “Financial Impact of Breast Cancer in Black Versus White Women,” J. Clin. Oncol, vol. 36, no. 17, pp. 1695–1701, June 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Jennifer L Beebe-Dimmer et al. , “The Detroit Research on Cancer Survivors (ROCS) Pilot Study: A focus on outcomes after cancer in a racially-diverse patient population,” Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev, July 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].“CDC - BRFSS - Questionnaires,” 18-Jan-2018. [Online]. Available: https://www.cdc.gov/brfss/questionnaires/index.htm. [Accessed: 28-Jan-2019].

- [25].Kochhar R and comments RF, “Wealth inequality has widened along racial, ethnic lines since end of Great Recession,” Pew Research Center, 12-December-2014. . [Google Scholar]

- [26].“Insurance Coverage Provisions of the Affordable Care Act--CBO’s March 2015 Baseline.” [Online]. Available: http://www.cbo.gov/sites/default/files/51298-2015-03-ACA.pdf. [Accessed: 17-Jan-2017].

- [27].Collins S, Rasmussen P, Beutel S, and Doty M, “The problem of underinsurance and how rising deductibles will make it worse. Findings from the Commonwealth Fund Biennial Health Insurance Survey, 2014.,” Issue Brief Commonw. Fund, vol. 13, pp. 1–20, May 2015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Yousuf Zafar S, “Financial Toxicity of Cancer Care: It’s Time to Intervene,” JNCI J. Natl. Cancer Inst, vol. 108, no. 5, May 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]