Abstract

Background

The aim of this study was to investigate the detailed motives, concerns, and psychological defensiveness of living liver donor candidates in a Korean population.

Material/Methods

We analyzed data of 102 donor candidates obtained from routine psychosocial evaluation for living donor liver transplantation (LDLT) using descriptive methods. Donor candidates completed 2 questionnaires regarding their motivations and concerns, as well as a validity scale, the K scale from the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory-2.

Results

Donor candidates were more likely to cite family-related issues (77.5% to 94.1%) including well-being of the whole family and family affection as the reasons for their liver donation rather than personal motives (38.2% to 57.8%). Donors were also more likely to concern about the recipient’s survival and recovery (52.9% to 58.8%) rather than their own difficulties such as surgical complications and occupational disadvantages (19.6% to 38.2%). Twenty-six donors (25.5%) took a psychologically defensive attitude (T-score of K scale ≥65) during the pre-donation evaluation. Psychologically defensive donors expressed a significantly lower level of concern about liver donation compared to non-defensive donors (P<0.01).

Conclusions

We need to pay more attention to the family-related issues and psychological defensiveness of living liver donor candidates when evaluating psychosocial status before LDLT.

MeSH Keywords: Decision Making, Liver Transplantation, Living Donors, Psychology

Background

Living donor liver transplantation (LDLT) is a life-saving treatment option for patients with end-stage liver disease when a deceased donor organ is not readily available. Especially in East Asia where sociocultural reasons limit the supply of organs from deceased donors, LDLT has been a mainstream treatment for end-stage liver disease, accounting for 70% to 90% of all liver transplantations [1,2]. However, LDLT requires the donor to undergo a major surgery with no medical benefit. Indeed, living liver donors bear not only a significant risk of surgical complications and mortality [3,4], but also financial and occupational disadvantages [5,6]. Therefore, choosing to become a living liver donor is not a simple decision. In most cases, a family member or relative volunteers to become a donor candidate, and there are many issues related to the donor, recipient or family that can play a role in this decision-making process [7].

Living liver donor candidates are highly motivated to participate in liver donation in order to save the life of the recipient. However, many donors are simultaneously concerned about the transplantation surgery. Therefore, in order to understand donor’s decision-making process, it is necessary to evaluate the detailed motives and concerns of the donors first. With respect to donor motivation, donors usually describe the desire to save the life of their loved one as their primary motive. Personal attitudes and values toward donation such as altruism, moral duty, and religious beliefs are important motivating factors for donors [8,9]. Familial relationship between donor and recipient strongly influences the level of donor’s motivation, especially in Asian cultures [1]. Family background or dynamics may also play a significant role in the donor’s decision-making process [10]. In addition, the suggestion or expectation of the recipient or family, even if not through coercion, may affect the donor’s decision-making, although this is uncommon [11]. On the other hand, concerns about post-donation outcomes can cause donor candidates to feel uneasy and ambivalent during the decision-making stage [12]. To a greater or lesser extent, most donors feel concern about the potential surgical complications and the effects of the surgery on their daily life, for example, wound pain and surgical scars, the recovery period after surgery, changes in their physical functions or health, and ability to return to their job, schoolwork, or housework [13,14]. Recipient outcome after transplantation is also of great concern to donors, and some donors may be ambivalent about liver donation because they think the recipient will not recover despite liver transplantation [15].

During pre-donation evaluation, some donor candidates may not want to reveal their true motivations or concerns. Some donors may not disclose their true concerns about liver donation, worrying that it may render them ineligible to donate. Specifically, it may be difficult for the donor to openly express their feelings about liver donation, including fear, regret, and resentment. However, these attitudes may mask true emotional burden of donor candidates leading to psychological problems after liver donation. Therefore, it is important to address the psychological defensiveness of living liver donors during the pre-donation evaluation. However, little is currently known about the prevalence of psychological defensiveness in donor candidates undergoing psychosocial evaluation before LDLT.

There have been some reports on donor decision-related factors in LDLT [12,13,16]. Most studies to date have focused on the donor’s own altruistic motivation, concerns, and feelings of ambivalence, whereas the influence of recipient or family-related factors on the donor’s decision-making has been less addressed. Thus, the aim of this study was to investigate the detailed motives and concerns of living liver donors covering not only personal issues but also recipient or family-related ones. In this study, we also compared the level of donor motivation and concern according to the type of relationship between donor and recipient. In addition, we assessed the psychologically defensive attitudes of donor candidates during pre-donation evaluation.

Material and Methods

Participants

We reviewed the medical records of 107 living liver donor candidates at the Transplantation Center of Samsung Medical Center, Korea who visited the psychosomatic clinic for pre-donation evaluation between December 2014 and February 2016. All donor candidates were ahead of the final stage of physical workup. They were interviewed about psychosocial factors including relationship with the recipient, readiness level, social support, and psychological stability and completed some questionnaires regarding their decision-related factors and psychological status as part of the routine protocol for psychosocial evaluation before LDLT. Data from 5 donors was either missing or incomplete, and thus data from 102 living liver donor candidates was included in our final analysis. The Institutional Review Boards of Samsung Medical Center approved the review of information obtained from donors’ records (IRB approval number: 2016-02-020-001). The requirement for informed consent was waived because of the retrospective nature of the study.

Assessments

We designed 2 self-rating questionnaires on the detailed motives and concerns of living organ donor candidates for use during pre-donation psychosocial evaluation in our center. The items on the questionnaires were generated by the authors (JMK and SR) and were based on the existing literature and the authors’ clinical experience over several years evaluating living organ donor candidates. All items were rated using a Likert scale from 0 (disagree) to 4 (agree very strongly). Donor candidates were asked about what motivated them to decide to undergo liver donation in 10 items on the donor motivation questionnaire. The questionnaire addressed not only self-related issues such as altruism, moral obligation, and religious beliefs, but also family-related issues such as family affection, well-being of the whole family, and family expectations. Donors were also asked to consider donation-related concerns about medical and psychosocial problems across 8 items on the donor concern questionnaire. We assumed that the high total score of each questionnaire represented a high level of donor motivation or concern. In addition, the psychological defensiveness of donors in the pre-donation evaluation was measured using the K scale (30 items) of the Korean version of the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory-2 (MMPI-2). The MMPI-2 is a standardized psychometric test of adult personality and psychopathology and the K scale from the MMPI-2 is a validity scale designed to detect test-taking defensiveness and is specifically useful in determining attempts to present oneself in a socially desirable light [17]. A high T-score (standard score) of the K scale (≥65) most likely indicates a defensive test-taking attitude or an attempt to falsely generate good results [18]. Therefore, in this study, we used a K scale T-score of 65 as a cutoff to divide donor candidates into psychologically defensive and non-defensive groups.

Statistical methods

Positive response rates based on “agree moderately”, “strongly”, or “very strongly” responses to individual items on the two questionnaires used to assess donor motivations and concerns were analyzed using descriptive statistics. Cronbach’s alpha estimate was computed to establish the internal consistency of the questionnaires. Construct validities were analyzed by exploratory factor analysis with principal component analysis followed by varimax rotation. To investigate the influence of the relationship between donor and recipient on the level of donor motivation and concern, we compared the total scores of each questionnaire according to the type of relationship between donor and recipient using the Kruskal-Wallis test and Mann-Whitney U test. In addition, to assess the degree to which psychologically defensive donors were reluctant to express their true motives and concerns, we compared the total scores of each questionnaire between psychologically defensive donors (T-score of K scale ≥65) and non-defensive donors (T-score of K scale <65) using an independent t-test. All statistical analyses were performed using Statistical Package for the Social Science (SPSS) version 21.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). P values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Demographic characteristics

Table 1 summarizes the demographic characteristics of the donor candidates. Among the 102 donors, there were 64 men (61.8%) and 38 women (38.2%) with a mean age of 33.54±11.33 years. Six donors (5.9%) were diagnosed with mental illness (depressive disorder, n=3; adjustment disorder, n=2; pathological gambling, n=1), but all were in remission at the time of pre-donation evaluation. An adult offspring was the most common donor candidate (n=65, 63.7%), followed by spouse (n=11, 10.8%), sibling (n=10, 9.8%), parent (n=9, 8.8%), and extended-family member (n=7, 6.9%) including nephew, grandson, daughter-in-law, and parent-in-law. There were no anonymous donors.

Table 1.

Demographics and clinical characteristics of donors (n=102).

| Variable | Value* |

|---|---|

| Age, years | 33.54±11.33 (18–61) |

| Gender, female, n | 39 (38.2%) |

| Marital status, n | |

| Single | 43 (42.2%) |

| Divorced | 2 (2.0%) |

| Married | 57 (55.9%) |

| Employment status, n | |

| Unemployed | 7 (6.9%) |

| Housewife | 16 (15.7%) |

| Student | 16 (15.7%) |

| Employed | 63 (61.8%) |

| Education beyond high school, n | 66 (64.7%) |

| Previous psychiatric history, n | 6 (5.9%) |

| Relationship of donor candidate with recipient, n | |

| Adult offspring | 65 (63.7%) |

| Parent | 9 (8.8%) |

| Sibling | 10 (9.8%) |

| Spouse | 11 (10.8%) |

| Extended family | 7 (6.9%) |

Data are given as mean±SD (range) or n (%).

Reliability and validity of the questionnaires

Cronbach’s alpha estimates for the donor motivation and concern questionnaires were 0.80 and 0.84, respectively, which indicated acceptable internal consistency. Factor analysis showed that “donor’s motivation” included 2 important factors, namely “helping others” and “family-related”; the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) value was 0.75, and the cumulative communality was 48.75%. “Donor’s concern” also comprised 2 important factors, namely, “self-related” and “family-related”; the KMO value was 0.82, and the cumulative communality was 65.35%. Bartlett’s test of sphericity was statistically significant for both questionnaires, which indicated acceptable scale structure and construct validity.

Motives of donor candidates

The positive response rates for individual items on the donor motivation questionnaire are indicated in Table 2. Three items about family-related issues, namely, “because it is desirable for the well-being of the whole family” (94.1%), “because I feel family affection for the recipient” (91.2%), and “because I don’t want another family member to suffer from organ donation” (77.5%) showed a very high positive response rate. However, relatively fewer donor candidates responded positively to items about altruism such as “to become a good person who can help others” (57.8%), “because I think organ donation is a special opportunity to do something helpful to others” (45.1%), and “according to my moral obligation to help others” (38.2%). In addition, some donors reported family expectation as a major reason for their donation, although this comprised a minority of cases (15.7%).

Table 2.

Motives and concerns of living liver donor candidates (n=102).

| Questions* | Score** | Positive response*** |

|---|---|---|

| Donor motivation questionnaire (10 items) | ||

| I am donating to become a good person who can help others | 2 (0–3) | 59 (57.8) |

| I am donating because I don’t want another family member to suffer from organ donation | 3 (2–4) | 79 (77.5) |

| I am donating because I have empathy for the recipient | 2 (0–3) | 60 (58.8) |

| I am donating because it is desirable for the well-being of the whole family | 4 (2–4) | 96 (94.1) |

| I am donating according to my religious belief that I should help others | 0 (0–0) | 13 (12.7) |

| I am donating according to the traditional values of family | 1 (0–3) | 50 (49.0) |

| I am donating according to my moral obligation to help others | 1 (0–2) | 39 (38.2) |

| I am donating because of the expectation of family to help the recipient | 0 (0–1) | 16 (15.7) |

| I am donating because I think organ donation is a special opportunity to do something helpful for others | 1 (0–3) | 46 (45.1) |

| I am donating because I feel family affection for the recipient | 4 (2–4) | 93 (91.2) |

| Donor concern questionnaire (8 items) | ||

| I am concerned about the surgical scar | 1 (0–1.25) | 25 (24.5) |

| I am concerned that the recipient can manage his or her health after organ transplantation | 2 (1–3) | 60 (58.8) |

| I am concerned that I may have to temporarily stop my work after organ donation | 1 (0–2) | 39 (38.2) |

| I am concerned that the condition of the recipient may worsen even after transplantation surgery | 2 (1–3) | 54 (52.9) |

| I am concerned that my physical functions will worsen | 1 (0–1) | 20 (19.6) |

| I am concerned about wound pain | 1 (0–2) | 29 (28.4) |

| I am concerned that my family will worry about my decision for organ donation | 1 (1–2) | 45 (44.1) |

| I am concerned that organ donation will cause me health problems in the future | 1 (0–1) | 22 (21.6) |

All items on the questionnaires were rated using a 5-point Likert scale (0, disagree; 1, agree slightly; 2, agree moderately; 3, agree strongly; 4, agree very strongly);

median (interquartile range);

agree moderately, strongly, or very strongly, n (%).

Concerns of donor candidates

The positive response rates for individual items on the donor concern questionnaire are shown in Table 2. About half of the donor candidates responded positively to items about their concerns for the recipient such as “I am concerned that the recipient can manage his or her health after organ transplantation” (58.8%) and “I am concerned that the condition of the recipient may be worse even after transplantation surgery” (52.9%). In addition, many donors were concerned that their family would worry about their decision to donate part of their liver (44.1%). However, the positive response rates for the items of concern about the donor’s own issues were relatively less than those for items of concern about the recipient or the family. With respect to donor’s own personal concerns, some donors expressed concerns about occupational problems after surgery (38.2%), wound pain (28.4%), surgical scar (24.5%), future health problems (21.6%), and deterioration of their physical function (19.6%).

Comparisons of motivation and concern according to the type of relationship between donor and recipient

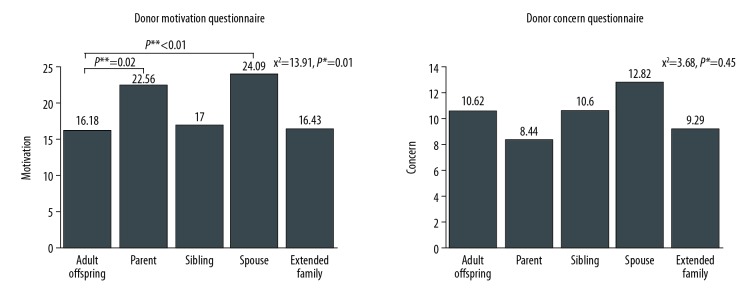

A significant difference was found in the level of donor motivation (χ2=13.91, P=0.01) according to the type of relationship between donor and recipient, although this was not the case for donation-related concerns (χ2=3.68, P=0.45). Specifically, parents donating for their children (U=151.50, P=0.02) and husbands or wives donating for their spouses (U=146.00, P<0.01) had a significantly higher level of motivation compared to adult offspring donating to their parents (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Motivations and concerns of living liver donor candidates according to donor-recipient relationship type. * Kruskal-Wallis test; ** Mann-Whitney U test.

Psychological defensiveness of donor candidates

The mean T-score of the K scale was 57.49±10.02, and there were 26 donor candidates (25.5%) with a T-score ≥65. There was no difference in T-score with respect to employment status, education level, and relationship type. Likewise, we did not observe a difference in the level of donor motivation between psychologically defensive donors and non-defensive donors. However, psychologically defensive donors expressed significantly lower levels of concern about liver donation than non-defensive donors (t=2.95, P<0.01) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Motivations and concerns of living liver donor candidates: Comparison between psychologically defensive donors and non-defensive donors*.

| Defensive donors (n=26) | Non-defensive donors (n=76) | Statistic | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Motivation | 17.73±9.12 | 17.68±7.12 | t=−0.03, P=0.98 |

| Concern | 7.50±5.13 | 11.62±6.44 | t=2.95, P<0.01 |

Depending on the T-score of K scale from the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory-2 (MMPI-2), donors were divided into psychologically defensive donors (T-score of K scale ≥65) and non-defensive donors (T-score of K scale <65).

Discussion

In the present study, we investigated the detailed motives and concerns of living liver donor candidates using questionnaires developed by the authors. Using surveys, we found that donor candidates took into consideration a variety of issues about their family or recipient when deciding to become a living liver donor. In addition, by assessing the psychological defensiveness of living liver donor candidates in a psychosocial evaluation, we found that psychologically defensive donor candidates under-reported their concerns about liver donation before transplantation surgery.

Family-related issues play an important role in a donor’s decision to participate in liver donation beyond their own altruistic motivations. Above all, the family relationship between a donor and recipient is the most important reason why individuals volunteer for liver donation despite the numerous difficulties associated with transplantation surgery [16]. In Confucian culture, traditional family values such as filial piety may be an important motivation for liver donation [19]. In this study, most of the donor candidates were an immediate family member of the recipient and cited “family affection for the recipient” as the reason for their liver donation. The well-being or expectation of other family members was another important consideration reported by donors as being part of the donation decision-making process. Indeed, the results of our survey showed that many donor candidates decided to participate in liver donation “for the well-being of the whole family” (94.1%) or “because of not wanting another family member to suffer difficulties” (77.5%). In a small number of donors (15.7%), expectation of the family was also reported as a main reason for participating in liver donation. However, such family-related issues in the donor’s decision-making have not been well addressed in previous studies investigating the decision-related factors of living liver donors. Some studies conducted in Japan have suggested that the family’s influence on the decision-making process for liver donation might increase the psychological burden on the donor. According to Hayashi et al., donor candidates who report conflict between family members associated with the donor decision-making process have high levels of anxiety, symptoms of depression, and a low quality of life [20]. Likewise, Uehara et al. reported that donors whose family made a decision regarding liver donation without an explicit discussion experienced a higher level of anxiety [21]. Considering that family-related issues may increase the donor’s psychological burden, it is necessary to evaluate the family’s influence on the donor’s decision-making when assessing the donor’s psychosocial status before transplantation surgery. To this end, further studies to develop assessment tools for the familial relationship of potential living liver donors are warranted, and pre-donation evaluation also needs to include a survey of family dynamics around the donor candidates.

There have been some reports on the detailed concerns of living liver donor candidates. A retrospective study investigating the decision-related factors of Korean living liver donors showed that approximately half of donors report feeling anxiety when deciding on liver donation, the reasons for which include “inability to sustain a normal life”, “pain related to surgery”, “fear of death after surgery”, and “complications after surgery” [16]. Lai et al. reported that Taiwanese living liver donors are mainly concerned with not only the “medical cost of the living liver surgery” and “not having enough resources to take care of the donor”, but also “successful outcome of the recipient after the operation” [15]. Several of the donors evaluated in our study described feeling concern about the recipient’s post-donation outcome, while relatively fewer donors were concerned about surgical complications and occupational problems after the surgery. These findings apparently suggest that donor candidates are more interested in the recipient’s survival and recovery to normal life than their own difficulties, when deciding on liver donation. Given that death of the recipient may lead to a deterioration of the donor’s mental health and their quality of life [22], concerns about the recipient’s outcomes may negatively influence the donor’s psychological status and may increase the donor’s ambivalent attitude before transplantation surgery [15]. Therefore, it is necessary to closely assess the concerns of donors regarding the recipient’s post-donation outcome as well as their own physical or psychosocial problems following liver donation through a pre-donation evaluation.

In this study, we found that there was a difference in the level of donor motivation according to relationship between the donor and the recipient. Adult offspring donating for their parents reported a relatively lower level of motivation compared to parents donating for their children and husbands or wives donating for their spouses. This finding was consistent with a previous study on relationship type and donation, the results of which showed that parents donating to their children have relatively low levels of anxiety and depressive symptoms before LDLT, while adult offspring donating to a parent have the highest emotional strain and lowest emotional quality of life [23]. The lower level of donor motivation observed among adult offspring may be because they feel that they have no other choice due to traditional values and the social expectation to care for their sick parent [24]. On the other hand, we did not find a difference in the level of donor concern about liver donation according to relationship between the donor and the recipient. This might be because donor concern is often a problem which comes from donor’s own personal perspective, unlike donor motivation which is highly influenced by the familial relationship with the recipient.

During psychosocial evaluation for LDLT, some donor candidates may not want to reveal their true motivations for donating or their feelings about liver donation, including fear and regret. Specifically, some donors may worry that if they express their thoughts honestly, they will not be able to donate. In addition, some donors may have difficulty verbalizing their emotions either inherently or due to stressful circumstances. In the present study, one quarter of donor candidates took a psychologically defensive attitude in the questionnaires. We also found that the level of concern about liver donation was significantly lower in psychologically defensive donors, although the level of donor motivation did not differ depending on psychological defensiveness. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study of the psychological defensiveness of living liver donor candidates. Our findings suggest that some donor candidates might provide false answers during the pre-donation evaluation by selectively under-reporting their donation-related concerns. If donor candidates intend to hide their true thoughts or feelings about liver donation, clinicians or family members are more likely to overlook their psychological burden before transplantation surgery. However, psychologically defensive donors are more likely to experience more serious psychological problems compared to non-defensive donors. According to Uehara et al., living liver donors who exhibit difficulties during the individual or family decision-making process tend to show alexithymia, a deficiency in processing and describing one’s emotional feelings [21]. Therefore, it is necessary to assess donor’s psychological defensiveness during the pre-donation evaluation and to carefully observe the psychological status of defensive donors. In particular, clinicians should not overlook the possibility that the defensive donors under-report their psychological distress, and should follow up on their psychological post-donation outcome.

The findings of this study may be specific to Korean culture, and thus will need to be confirmed in East Asian and Western studies. This study was also limited by its retrospective design in which we analyzed data from questionnaires completed by donor candidates during routine psychosocial evaluation for LDLT. The questionnaires had originally been designed for simple clinical use in our center and had not been fully validated. Specifically, in this study, we confirmed the internal consistency and construct validity of the questionnaires for donor motivation and concern, but we could not assess the test-retest reliability and concurrent validity. In addition, we could not apply the other validity indices of MMPI-2 such as F, F-K, and FBS (Fake Bad Scale) to distinguish psychologically defensive donors in the pre-donation evaluation [25].

In summary, within the context of the aforementioned limitations, the findings of this study suggest that both recipient and family-related factors may have an important influence on the donor’s decision-making process in LDLT. In addition, this study showed that there are psychologically defensive donors who under-report their concerns about transplantation surgery during the pre-donation evaluation. Prospective studies using well-validated scales to assess decision-related factors and psychological defensiveness of living liver donor candidates are warranted.

Conclusions

We need to pay attention to the recipient and family-related issues of living liver donor candidates in their decision-making process. In addition, careful consideration should be given to their psychological defensiveness when evaluating psychosocial status before LDLT.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

None.

Source of support: This work was supported by a clinical research grant (code 2018-12) from the National Center for Mental Health, Republic of Korea

References

- 1.Chen CL, Kabiling CS, Concejero AM. Why does living donor liver transplantation flourish in Asia? Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;10:746–51. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2013.194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee SG. Living-donor liver transplantation in adults. Br Med Bull. 2010;94:33–48. doi: 10.1093/bmb/ldq003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abecassis MM, Fisher RA, Olthoff KM, et al. Complications of living donor hepatic lobectomy – a comprehensive report. Am J Transplant. 2012;12:1208–17. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2011.03972.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ghobrial RM, Freise CE, Trotter JF, et al. Donor morbidity after living donation for liver transplantation. Gastroenterology. 2008;135:468–76. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.04.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.DiMartini A, Dew MA, Liu Q, et al. Social and financial outcomes of living liver donation: A prospective investigation within the Adult-to-Adult Living Donor Liver Transplantation Cohort Study 2 (A2ALL-2) Am J Transplant. 2017;17(4):1081–96. doi: 10.1111/ajt.14055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim JM. Rehabilitation for social reintegration in liver transplant patients. Clin Mol Hepatol. 2018;24:370–71. doi: 10.3350/cmh.2018.1012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Biller-Andorno N. Voluntariness in living-related organ donation. Transplantation. 2011;92:617–19. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e3182279120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Papachristou C, Walter M, Dietrich K, et al. Motivation for living-donor liver transplantation from the donor’s perspective: An in-depth qualitative research study. Transplantation. 2004;78:1506–14. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000142620.08431.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Walter M, Papachristou C, Danzer G, et al. Willingness to donate: An interview study before liver transplantation. J Med Ethics. 2004;30:544–50. doi: 10.1136/jme.2003.004879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Abdeldayem H, Kashkoush S, Hegab BS, et al. Analysis of donor motivations in living donor liver transplantation. Front Surg. 2014;1:25. doi: 10.3389/fsurg.2014.00025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Scheper-Hughes N. The tyranny of the gift: Sacrificial violence in living donor transplants. Am J Transplant. 2007;7:507–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2006.01679.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.DiMartini A, Cruz RJ, Jr, Dew MA, et al. Motives and decision making of potential living liver donors: Comparisons between gender, relationships and ambivalence. Am J Transplant. 2012;12:136–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2011.03805.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.DuBay DA, Holtzman S, Adcock L, et al. Adult right-lobe living liver donors: Quality of life, attitudes and predictors of donor outcomes. Am J Transplant. 2009;9:1169–78. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2009.02614.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kang SH, Choi Y, Han HS, et al. Fatigue and weakness hinder patient social reintegration after liver transplantation. Clin Mol Hepatol. 2018;24:402–8. doi: 10.3350/cmh.2018.0028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lai YC, Lee WC, Juang YY, et al. Effect of social support and donation-related concerns on ambivalence of living liver donor candidates. Liver Transpl. 2014;20:1365–71. doi: 10.1002/lt.23952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee SH, Jeong JS, Ha HS, et al. Decision-related factors and attitudes toward donation in living related liver transplantation: Ten-year experience. Transplant Proc. 2005;37:1081–84. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2005.01.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Graham JR. MMPI-2: Assessing personality and psychopathology. 4th edition ed. New York: Oxford University Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim J, Han K, Lim J, et al. Korean MMPI-2 user manual. Seoul: Maumsarang; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Oliver M, Woywodt A, Ahmed A, Saif I. Organ donation, transplantation and religion. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2011;26:437–44. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfq628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hayashi A, Noma S, Uehara M, et al. Relevant factors to psychological status of donors before living-related liver transplantation. Transplantation. 2007;84:1255–61. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000287455.70815.9e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Uehara M, Hayashi A, Murai T, Noma S. Psychological factors influencing donors’ decision-making pattern in living-donor liver transplantation. Transplantation. 2011;92:936–42. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e31822e0bb5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Butt Z, Dew MA, Liu Q, et al. Psychological outcomes of living liver donors from a multicenter prospective study: Results from the Adult-to-Adult Living Donor Liver Transplantation Cohort Study2 (A2ALL-2) Am J Transplant. 2017;17(5):1267–77. doi: 10.1111/ajt.14134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Erim Y, Beckmann M, Kroencke S, et al. Influence of kinship on donors’ mental burden in living donor liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2012;18:901–6. doi: 10.1002/lt.23466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fujita M, Akabayashi A, Slingsby BT, et al. A model of donors’ decision-making in adult-to-adult living donor liver transplantation in Japan: having no choice. Liver Transpl. 2006;12:768–74. doi: 10.1002/lt.20689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Meyers JE, Millis SR, Volkert K. A validity index for the MMPI-2. Arch Clin Neuropsychol. 2002;17:157–69. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]