Abstract

Context:

To reduce the magnitude of antimicrobial resistance, there is a need to strengthen the knowledge for future prescribers regarding use and prescription of antibiotics. Before that, it is required to have a conclusive evidence about knowledge, attitude, and practices of that group.

Aim:

To assess the knowledge, attitudes, and the practices of medical students in India with respect to antibiotic resistance and usage.

Settings and Design:

It was a cross-sectional study which was done online through Google forms for a period of 4 months from July to October 2018.

Materials and Methods:

A structured questionnaire containing a five-point Likert scale was sent to medical students across India by sharing link through contacts of Medical Students Association of India. Respondent-driven sampling technique was also adopted for the study.

Statistical Analysis Used:

Descriptive statistics, parametric (Chi-square), and nonparametric (Kruskal--Wallis and Mann--Whitney U) tests.

Results:

A total of 474 responses were received from 103 medical colleges across 22 states of India. The mean score of knowledge was 4.36 ± 0.39. As compared to first year students, knowledge was significantly higher among students of all the years. As much as 83.3% students have consumed antibiotics in previous year of the survey. Around 45% of medical students accepted that they buy antibiotics without a medical prescription.

Conclusion:

The knowledge level of medical students was quite satisfactory. As far as attitude and practices are concerned, there is a substantial need for improvements.

Keywords: Antibiotic resistance, knowledge, medical students, practices

Introduction

The era of antibiotics has changed the pattern of treatment and outcomes of infectious diseases. But at the same time, irrational use of antibiotics has created a havoc of antibiotic resistance.[1] Worldwide spread of the antibiotic resistant organisms has gradually created the threat of antimicrobial insufficiency. Patients infected with these antibiotic resistant organisms are likely to face long durations of hospital stay and require treatment with second- and third-line drugs, which may be more toxic and less effective.[2]

Medical students are going to be primary care physicians to serve the community. These future prescribers are frontline fighters against antimicrobial resistance, by rationally prescribing the antibiotics and promoting patient awareness.[3] There are sufficient evidences to support that newly licensed doctors/prescribers are not adequately trained to prescribe medications safely.[4,5] Lack of adequate training during medical degree course may be one of the reasons for that.

There is a need to change the antimicrobial prescribing behavior of doctors and future prescribers to reduce the magnitude of the problem of antimicrobial resistance.[6] This can be ensured through the appropriate knowledge and training of next generation doctors and medical students through in a formal way.[7,8] But, before planning or strengthening any teaching or training program for any target group, it is required to have a conclusive evidence about baseline knowledge, attitude, and practices of that group. This evidence support in devising an effective curriculum and sustainable program. With this background, this study was planned with the objective to assess the knowledge, attitudes, and the practices of medical students in India with respect to antibiotic resistance and usage.

Subjects and Methods

It was a cross-sectional study which was done online through Google forms from July to October 2018. Data were collected through specifically developed structured questionnaire, which was developed based on the literature review of comparable studies.[9,10] This was validated by a pilot study on 30 medical students. The questionnaire had three sections. First section was dealing with basic information about medical students like; names, year of study, name of medical college etc., The second section was having 15 different statements (ten positive and five negative) on a five-point Likert scale ranging from one (strongly disagree) to five (strongly agree) to assess the knowledge of students. In this, three statements were related to identification of antibiotics, three related to role of antibiotics, three regarding side effects of antibiotics, and six were related to knowledge about antibiotic resistance. Section three was having questions for assessment of attitude and practices.

The questionnaire was sent to medical students across India by sharing link through contacts of Medical Students Association of India which has many students from medical institutes across India as its members. They were asked to recruit further respondents into the study from their respective colleges. Thus, a respondent-driven sampling technique was also adopted for the study.

The study was approved by an institutional ethics committee. Informed consent was taken before attempting the questionnaire. The purpose of the study was explained before starting the questionnaire and queries of all natures related to this research were invited for satisfactory explanation to ensure informed consent for participation. Data were analyzed using SPSS v. 23 and Microsoft Excel 2016. Appropriate tables and graphs were prepared and inferences were drawn by applying descriptive statistics, parametric (Chi-square) and nonparametric (Kruskal--Wallis and Mann--Whitney U) tests.

Results

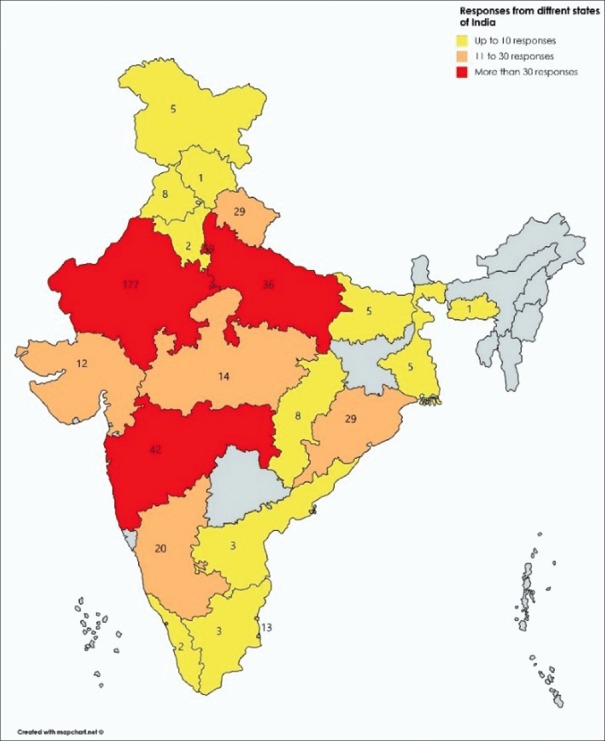

Figure 1 depicts that a total of 474 responses were received from 103 medical colleges distributed across 22 states of India. Maximum responses were received from Rajasthan (177) followed by Delhi (59), Maharashtra (42), and Uttar Pradesh (36).

Figure 1.

Distribution of responses from the different states of the country

As much as 32.3% of the students accepted that any of their family member was working in health-related field. The descriptive of knowledge about antibiotics and its resistance in terms of mean score, mean score%, and median for each statement is depicted in Table 1.

Table 1.

Descriptive of knowledge about antibiotics and its resistance

| Knowledge about | Statements | Mean score** | Mean score %*** | Median |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Identification | Penicillin or amoxicillin are antibiotics | 4.89 | 97.3 | 5 |

| Aspirin is an antibiotic* | 1.16 | 4.0 | 1 | |

| Paracetamol is an antibiotic* | 1.24 | 6.0 | 1 | |

| Role of antibiotics | Antibiotics are useful for bacterial infections (e.g., tuberculosis) | 4.67 | 91.8 | 5 |

| Antibiotics are useful for viral infections (e.g. common cold, flu)* | 1.61 | 15.3 | 1 | |

| Antibiotics are indicated to reduce any kind of pain and inflammation* | 1.61 | 15.3 | 1 | |

| Side-effects of antibiotics | Antibiotics can kill “good bacteria” present in our body | 4.34 | 83.5 | 5 |

| Antibiotics can cause secondary infections after killing good bacteria in our body | 4.12 | 78.0 | 5 | |

| Antibiotics can cause allergic reactions | 4.46 | 86.5 | 5 | |

| Antibiotic resistance | Ampicillin is effective in treating Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) infections* | 2.09 | 27.3 | 1 |

| Clindamycin is effective in treating MRSA infections | 3.05 | 51.3 | 3 | |

| Antibiotic resistance is a phenomenon in which a bacterium loses its sensitivity to an antibiotic | 4.72 | 93.0 | 5 | |

| Misuse of antibiotics can lead to a loss of sensitivity of an antibiotic to a specific pathogen | 4.72 | 93.0 | 5 | |

| If symptoms improve before completing the full course of antibiotic, you can stop taking it* | 1.45 | 11.3 | 1 | |

| Poor or lack of infection control measures is a cause for development of resistance | 3.61 | 65.3 | 4 |

*Negative statements. **{(total responses in strongly disagree x 1) + (total responses in disagree x 2) + (total responses in neutral x 3) + (total responses in agree x 4) + (total responses in strongly agree x 5)}/total responses (474). ***mean score % = (mean score-1) *100/(5-4)

Table 2 depicts that maximum (40%) students were studying in prefinal year, followed by second year (27%). Reverse coding was done for five negative statements for calculating the mean score for each participant. The overall mean score was 4.36 ± 0.39. A significant difference was observed in knowledge level of students according to their year of study.

Table 2.

Distribution of respondents according to their year of study and mean score of knowledge

| Year | n | Mean score | Mean rank | Kruskal--Wallis | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First year | 68 | 4.10±0.35 | 139.86 | 73.395 | <0.01 |

| Second year | 128 | 4.27±0.40 | 205 | ||

| Prefinal year | 187 | 4.52±0.32 | 293.45 | ||

| Final year | 68 | 4.38±0.39 | 242.35 | ||

| Internship | 23 | 4.34±0.44 | 237.8 | ||

| Total | 474 | 4.36±0.39 |

Bold values represent statistical significance

To explore the exact level of difference between each category, Mann--Whitney U test was applied [Table 3].

Table 3.

Comparison of mean score of knowledge according to their year of study

| Year | Mean rank | Year | Mean rank | Mann--Whitney U | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First year | 80.86 | Second year | 107.87 | 3152.5 | 0.001 |

| 68.21 | Prefinal year | 149.74 | 2292 | <0.01 | |

| 53.57 | Final year | 83.43 | 1296.5 | <0.01 | |

| 40.73 | Internship | 61.59 | 423.5 | 0.001 | |

| Second year | 123.31 | Prefinal year | 181.74 | 7528 | <0.01 |

| 93.09 | Final year | 108.69 | 3659 | 0.066 | |

| 74.23 | Internship | 85.87 | 1245 | 0.239 | |

| Prefinal year | 135.4 | Final year | 107.65 | 4974.5 | 0.008 |

| 108.57 | Internship | 80.54 | 1576.5 | 0.036 | |

| Final year | 46.07 | Internship | 45.8 | 777.5 | 0.967 |

Bold values represent statistical significance

Table 4 represents the attitude and practices of medical students regarding use of antibiotics. As much as 83.3% students have consumed antibiotics in previous year of the survey. Most of them have consumed antibiotics for once to three times in the whole year. Major source of information about antibiotics and its resistance was their degree courses.

Table 4.

Attitude and practices of medical students regarding use of antibiotics

| Year, n (%) | Total | Sig. | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First | Second | Pre Final | Final | Interns | |||

| Used antibiotics in the last year | 47 (69.1) | 116 (90.6) | 153 (81.8) | 58 (85.3) | 21 (91.3) | 395 (83.3) | 0.003 |

| Number of times antibiotics used in last year (n=395) | |||||||

| 1 | 8 (17.0) | 28 (24.1) | 38 (24.8) | 13 (22.4) | 9 (42.9) | 96 (24.3) | 0.247 |

| 2 | 10 (21.3) | 44 (37.9) | 45 (29.4) | 15 (25.9) | 4 (19.0) | 118 (29.9) | 0.142 |

| 3 | 10 (21.3) | 20 (17.2) | 38 (24.8) | 18 (31.0) | 2 (9.5) | 88 (22.3) | 0.144 |

| 4 | 9 (19.1) | 11 (9.5) | 20 (13.1) | 9 (15.5) | 2 (9.5) | 51 (12.9) | 0.492 |

| ≥5 | 10 (21.3) | 13 (11.2) | 12 (7.8) | 3 (5.2) | 4 (19.0) | 42 (10.6) | 0.036 |

| Heard about antibiotic resistance | 68 (14.3) | 128 (27.0) | 187 (39.5) | 68 (14.3) | 23 (4.9) | 474 (100) | NA |

| Source of information about antibiotic resistance | |||||||

| Academic course | 27 (39.7) | 119 (93.0) | 181 (96.8) | 63 (92.6) | 21 (91.3) | 411 (86.7) | <0.01 |

| General practitioner | 12 (23.1) | 39 (38.2) | 36 (27.3) | 23 (40.4) | 6 (35.3) | 116 (32.2) | 0.138 |

| Internet | 24 (46.2) | 39 (38.2) | 56 (42.4) | 21 (36.8) | 9 (52.9) | 149 (41.4) | 0.665 |

| Television | 14 (26.9) | 8 (7.8) | 9 (6.8) | 8 (14.0) | 0 (0.0) | 39 (10.8) | 0.001 |

| Newspaper | 17 (32.7) | 26 (25.5) | 36 (27.3) | 13 (22.8) | 1 (5.9) | 93 (25.8) | 0.264 |

| Discussion at home/school/friends | 2 (3.8) | 4 (3.9) | 3 (2.3) | 4 (7.0) | 1 (5.9) | 14 (3.9) | |

| Usually take antibiotic for cold or sore throat | 19 (27.9) | 29 (22.7) | 39 (20.9) | 21 (30.9) | 2 (8.7) | 110 (23.2) | 0.17 |

| Usually take antibiotic for fever | 30 (44.1) | 22 (17.2) | 23 (12.3) | 8 (11.8) | 2 (8.7) | 85 (17.9) | <0.01 |

| Usually stop taking antibiotic when start feeling better | 29 (42.6) | 38 (29.7) | 44 (23.5) | 17 (25.0) | 3 (13.0) | 131 (27.6) | 0.016 |

| Buy antibiotics without a medical prescription | 26 (38.2) | 52 (40.6) | 85 (45.5) | 40 (58.8) | 12 (52.2) | 215 (45.4) | 0.093 |

| Keep leftovers antibiotics for use in future | 45 (66.2) | 82 (64.1) | 118 (63.1) | 45 (66.2) | 15 (65.2) | 305 (64.3) | 0.987 |

| Use leftovers antibiotics without consulting the doctor | 21 (30.9) | 33 (25.8) | 49 (26.2) | 27 (39.7) | 6 (26.1) | 136 (28.7) | 0.252 |

| Ever started antibiotic therapy after getting consultation from doctor over phone, without a proper medical prescription | 30 (44.1) | 63 (49.2) | 102 (54.5) | 44 (64.7) | 13 (56.5) | 252 (53.2) | 0.14 |

Bold values represent statistical significance

Discussion

This study has tried to explore the knowledge, attitude, and practices of medical students regarding antibiotic resistance, as they are going to become future prescribers to provide the primary care to the community. Studies advocate that medical students generally have positive attitudes about antimicrobial resistance.[11,12] There are also supportive evidence to prove that practices of self-medication is more prevalent among medical students as compared to their peer group from the nonmedical fields.[13]

Knowledge about antibiotics and its resistance

In the present study, majority of the students could correctly identify the antibiotics. Similar kinds of knowledge regarding identification of antibiotics have been observed by Scaioli et al. (2015)[9] among students of a school of medicine in Italy and Sharma et al. (2016)[14] among medical students in Kerala, India.

The level of knowledge about the fact that antibiotics are useful for bacterial infections was quite high (91.8%) among medical students. Similar level of knowledge has been witnessed by many other studies.[9,10] Most of the students in the present study expressed their denial to the statement that antibiotics are useful for viral infections like common cold and flu. Comparable findings have been observed by Ahmad et al., (2015) among B. Sc. Pharmacy students of Trinidad[15] and Nair et al. (2019) among allopathic doctors in India[16]. Many studies have reported low level of awareness among students in this regard.[17,18,19] A high level of disagreement (84.7%) was observed among the students to the point that antibiotics are indicated to reduce pain and inflammation in the body. Similar kind of disagreement has been observed by Sakeena et al. (2018)[19] and Jamshed et al. (2014).[20] Contrary to these, Ajibola et al. (2018) had observed relatively lower level of disagreement (62.8%) in this regard.[17]

The magnitude of knowledge about side effects of antibiotics was ranging from 78% to 86.5% among medical students, which is lower than the findings observed by Scaioli et al. (2015) and Jamshed et al. (2014).[9,20] The knowledge about the kinds of antibiotics used for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) infections was not satisfactory among medical students. Majority of the students were aware about the mechanism of antibiotic resistance and also accepted that misuse of antibiotics can lead to antibiotic resistance to a specific pathogen. Similar findings have been reported by many studies.[9,15,19] There are other studies also in which understanding of students about the basic mechanism of antimicrobial resistance was reported quite lower.[17,21,22,23] As much as 88.7% disagreement was observed for the statement that, “if symptoms improve before completing the full course of antibiotic, you can stop taking it.” Mixed findings have been observed by many authors in this regard.[3,15,17,19,20,24] The mean score percentage of awareness for the fact that poor or lack of infection control measures is a cause for development of resistance was 63% in the present study. Similar level of awareness has been coated by other studies from different parts of the world.[21,22,25]

The overall mean score of knowledge for the students was 4.36 ± 0.39. Ayepola et al. (2018) found the mean knowledge score as 5.51 ± 0.14 (out of 10).[24] Jairoun et al. (2019) found the total knowledge attitude and practice (KAP) score pertaining to antibiotic use as 56 (on a scale of 0-100).[26] A significant difference was observed in knowledge level of students according to their year of study. Similar kinds of observations has been made by Huang et al. (2013).[10]

As compared to first year students, mean score of knowledge was significantly higher among students of all the years. This is supported by the findings of Huang et al. (2013).[10] A significantly better knowledge was also observed among pre final year students as compared to other years. This may be due to their updated knowledge of pharmacology which they have completed in recent past year.

Behaviors and practices of medical students regarding use of antibiotics

Majority (83.3%) of the students had used antibiotics in previous one year of the survey. This was relatively higher than the use reported by Scaioli et al. (2015),[9] Sakeena et al. (2018),[19] and Ayepola et al. (2018).[24]

In the present study, all the students had heard about antibiotic resistance. Similar level of awareness has been reported by Gupta et al. (2019) among medical students in India.[27] Lower level of knowledge in this regard has also been reported by many other studies.[10,17] Major source of information about antibiotic resistance for the first year students was internet, and for subsequent years it was through their academic course, followed by internet, general practitioners, newspaper, television, and discussions at home. Similar findings have been reported by other studies as well.[18,21,27]

Nearly, one fourth of students gave positive affirmation regarding usually taking antibiotic for cold or sore throat. This practice was quite lower than reported by many other studies.[9,13,14,28] Huang et al. (2013) observed this practice among only 13.6% of Chinese students.[10] Slightly less than one fifth students accepted that they were usually taking antibiotics for fever, which is similar to the findings reported by Ahmad et al. (2015). Variable practices in this regard have been reported by many other studies.[3,9,10,29]

Every one out of four students were following wrong practice of stopping antibiotics when start feeling better without completing the full course, which is similar to the findings reported by Ghaieth et al. (2015). Studies have reported diverse findings regarding this practice.[9,14,24,29,30]

Similar to other studies,[13,29] in the present study slightly less than half of medical students accepted that they buy antibiotics without a medical prescription. This practice was somewhat higher than the practices reported by many other studies.[3,9,14,26] This self-medication practice was more prevalent among study participants of Sakeena et al. (2018)[19] and Ayepola et al. (2018).[24] Unlike other studies,[9,13] no significant difference has been observed in self-medication practice among medical students as per their year of study.

Around two third of students were having practice of keeping leftover antibiotics for future use. This was similar to the findings by Ayepola et al. (2018).[24] This practice was relatively lower (less than 50%) among medical students from southern part of India.[3,29]

As much as 28.7% students were using these leftovers antibiotics in future without consulting the doctor. Scaioli et al. (2015) found this figure as 17.7%.[9] Other studies have reported that most of the students give the leftover antibiotics to their friends, relatives, or roommate without doctor's consultation when they are sick.[14,17,29]

More than half of students accepted that they had ever started antibiotic therapy after getting consultation from doctor over phone, without a proper medical prescription. Scaioli et al. (2015) found this practice prevalent among around one third of students.[9] Jamshed et al. (2014) reported that 8.9% of students were having perception that prescribing antibiotics over the phone is good patient care since it can save time.[20]

Conclusion and Recommendations

The knowledge level of medical students regarding antibiotics and its resistance was quite satisfactory. As far as attitude and practices are concerned, there is a significant need for improvements. Since the medical students are going to be primary care physicians in near future, it is important to have proper guidelines in medical curriculum related to use and rational prescription of antibiotics. Further, there is need and scope to explore this area with large sample size and through multicentric studies.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.WHO. WHO Global Strategy for Containment of Antimicrobial Resistance [Internet]. WHO. [cited 2019 Feb 01]. Available from: http://www.who.int/drugresistance/WHO_Global_Strategy.htm/en/

- 2.Prestinaci F, Pezzotti P, Pantosti A. Antimicrobial resistance: A global multifaceted phenomenon. Pathog Glob Health. 2015;109:309–18. doi: 10.1179/2047773215Y.0000000030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Khan AKA, Banu G, Reshma KK. Antibiotic resistance and usage—A survey on the knowledge, attitude, perceptions and practices among the medical students of a Southern Indian Teaching Hospital. J Clin Diagn Res. 2013;7:1613–6. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2013/6290.3230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Petrov A. Skills of Bulgarian medical students to prescribe antibacterial drugs rationally: A pilot study. IMAB – Annu Proceeding Sci Pap. 2018;24:2020–3. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bianco A, Papadopoli R, Mascaro V, Pileggi C, Pavia M. Antibiotic prescriptions to adults with acute respiratory tract infections by Italian general practitioners. Infect Drug Resist. 2018;11:2199–205. doi: 10.2147/IDR.S170349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pulcini C, Williams F, Molinari N, Davey P, Nathwani D. Junior doctors’ knowledge and perceptions of antibiotic resistance and prescribing: A survey in France and Scotland. Clin Microbiol Infect Off Publ Eur Soc Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2011;17:80–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2010.03179.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.WHO Competency Framework for Health Workers’ Education and Training on Antimicrobial Resistance [Internet] 2018. Available from: http://apps.who.int/medicinedocs/documents/s23443en/s23443en.pdf .

- 8.Brinkman DJ, Tichelaar J, Graaf S, Otten RHJ, Richir MC, van Agtmael MA. Do final-year medical students have sufficient prescribing competencies? A systematic literature review. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2018;84:615–35. doi: 10.1111/bcp.13491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Scaioli G, Gualano MR, Gili R, Masucci S, Bert F, Siliquini R. Antibiotic use: A cross-sectional survey assessing the knowledge, attitudes and practices amongst students of a school of medicine in Italy. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0122476. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0122476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huang Y, Gu J, Zhang M, Ren Z, Yang W, Chen Y, et al. Knowledge, attitude and practice of antibiotics: A questionnaire study among 2500 Chinese students. BMC Med Educ. 2013;13:163. doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-13-163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chuenchom N, Thamlikitkul V, Chaiwarith R, Deoisares R, Rattanaumpawan P. Perception, attitude, and knowledge regarding antimicrobial resistance, appropriate antimicrobial use, and infection control among future medical practitioners: A multicenter study. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2016;37:603–5. doi: 10.1017/ice.2016.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dyar OJ, Pulcini C, Howard P, Nathwani D ESGAP (ESCMID Study Group for Antibiotic Policies) European medical students: A first multicentre study of knowledge, attitudes and perceptions of antibiotic prescribing and antibiotic resistance. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2014;69:842–6. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkt440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ghaieth MF, Elhag SRM, Hussien ME, Konozy EHE. Antibiotics self-medication among medical and nonmedical students at two prominent Universities in Benghazi City, Libya. J Pharm Bioallied Sci. 2015;7:109–15. doi: 10.4103/0975-7406.154432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sharma S, Jayakumar D, Palappallil D, Kesavan K. Knowledge, attitude and practices of antibiotic usage and resistance among the second year MBBS Students. Int J Basic Clin Pharmacol. 2016;5:899–903. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ahmad A, Khan MU, Patel I, Maharaj S, Pandey S, Dhingra S. Knowledge, attitude and practice of B.Sc. Pharmacy students about antibiotics in Trinidad and Tobago. J Res Pharm Pract. 2015;4:37–41. doi: 10.4103/2279-042X.150057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nair M, Tripathi S, Mazumdar S, Mahajan R, Harshana A, Pereira A, et al. Knowledge, attitudes, and practices related to antibiotic use in Paschim Bardhaman district: A survey of healthcare providers in West Bengal, India. PLoS One. 2019;14:e0217818. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0217818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ajibola O, Omisakin O, Eze A, Omoleke S. Self-medication with antibiotics, attitude and knowledge of antibiotic resistance among community residents and undergraduate students in Northwest Nigeria. Diseases. 2018;6:32. doi: 10.3390/diseases6020032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Seid MA, Hussen MS. Knowledge and attitude towards antimicrobial resistance among final year undergraduate paramedical students at University of Gondar, Ethiopia. BMC Infect Dis. 2018;18:1–8. doi: 10.1186/s12879-018-3199-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sakeena MHF, Bennett AA, Jamshed S, Mohamed F, Herath DR, Gawarammana I, et al. Investigating knowledge regarding antibiotics and antimicrobial resistance among pharmacy students in Sri Lankan universities. BMC Infect Dis. 2018;18:209. doi: 10.1186/s12879-018-3107-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jamshed SQ, Elkalmi R, Rajiah K, Al-Shami AK, Shamsudin SH, Siddiqui MJA, et al. Understanding of antibiotic use and resistance among final-year pharmacy and medical students: A pilot study. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2014;8:780–5. doi: 10.3855/jidc.3833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wasserman S, Potgieter S, Shoul E, Constant D, Stewart A, Mendelson M, et al. South African medical students’ perceptions and knowledge about antibiotic resistance and appropriate prescribing: Are we providing adequate training to future prescribers? S Afr Med J. 2017;107:405–10. doi: 10.7196/SAMJ.2017.v107i5.12370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yang K, Wu D, Tan F, Shi S, Guo X, Min Q, et al. Attitudes and perceptions regarding antimicrobial use and resistance among medical students in Central China. Springer Plus. 2016;5:1779. doi: 10.1186/s40064-016-3454-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mersha AG. Attitude and perception of medical interns about antimicrobial resistance: A multi center cross-sectional study in Ethiopia. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2018;7:149. doi: 10.1186/s13756-018-0443-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ayepola OO, Onile-Ere OA, Shodeko OE, Akinsiku FA, Ani PE, Egwari L. Dataset on the knowledge, attitudes and practices of university students towards antibiotics. Data Brief. 2018;19:2084–94. doi: 10.1016/j.dib.2018.06.090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dyar O, Hills H, Seitz L-T, Perry A, Ashiru-Oredope D. Assessing the knowledge, attitudes and behaviors of human and animal health students towards antibiotic use and resistance: A pilot cross-sectional study in the UK. Antibiotics. 2018;7:1–10. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics7010010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jairoun A, Hassan N, Ali A, Jairoun O, Shahwan M, Hassali M. University students’ knowledge, attitudes, and practice regarding antibiotic use and associated factors: A cross-sectional study in the United Arab Emirates. Int J Gen Med. 2019;12:235–46. doi: 10.2147/IJGM.S200641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gupta R, Malhotra A, Malhotra P. Comparative assessment of antibiotic resistance among first and second year undergraduate medical students in a tertiary care teaching hospital. Int J Res Med Sci. 2019;7:481–5. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Badiger S, Kundapur R, Jain A, Kumar A, Pattanshetty S, Thakolkaran N, et al. Self-medication patterns among medical students in South India. Australas Med J. 2012;5:217–20. doi: 10.4066/AMJ.2012.1007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Padmanabha TS, Nandini T, Manu G, Savka MK, Shankar MR. Knowledge, attitude and practices of antibiotic usage among the medical undergraduates of a tertiary care teaching hospital: An observational cross-sectional study. Int J Basic Clin Pharmacol. 2016;5:2432–7. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sakeena MHF, Bennett AA, Carter SJ, McLachlan AJ. A comparative study regarding antibiotic consumption and knowledge of antimicrobial resistance among pharmacy students in Australia and Sri Lanka. PLoS One. 2019;14:e0213520. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0213520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]