Background:

The United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention promote HIV testing every 6 months among young men who have sex with men (YMSM) to facilitate entry into the HIV prevention and care continuum. Willingness to be tested may be influenced by testing services' quality. Using a novel mystery shopper methodology, we assessed YMSM's testing experiences in 3 cities and recommend service delivery improvements.

Methods:

We assessed YMSM's experiences at HIV testing sites in Philadelphia (n = 30), Atlanta (n = 17), and Houston (n = 19). YMSM (18–24) were trained as mystery shoppers and each site was visited twice. After each visit, shoppers completed a quality assurance survey to evaluate their experience. Data were pooled across sites, normed as percentages, and compared across cities.

Results:

Across cites, visits averaged 30 minutes (SD = 25.5) and were perceived as welcoming and friendly (70.9%). YMSM perceived most sites respected their privacy and confidentiality (84.3%). YMSM noted deficiencies in providers' competencies with sexual minorities (63.4%) and comfort during the visit (65.7%). Sites underperformed on Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender visibility (49.6%) and medical forms inclusivity (57.95%). Sites on average did not discuss YMSM's relationship context (49.8%) nor provide risk reduction counseling (56.8%) or safer sex education (24.3%). Sites delivered pre-exposure prophylaxis information and counseling inconsistently (58.8%).

Conclusions:

Testing sites' variable performance underscores the importance of improving HIV testing services for YMSM. Strategies are recommended for testing sites to promote cultural sensitivity: funding staff trainings, creating systems to assess adherence to testing guidelines and best practices, and implementing new service delivery models.

Key Words: quality assurance, mystery shopping, testing resources, systems, community

INTRODUCTION

Improving rates of HIV testing among young men who have sex with men (YMSM) is a crucial public health strategy for stemming the increasing HIV epidemic in the United States and achieving the Ending the HIV Epidemic in the United States by 2030 initiative.1 Although both research and intervention efforts have been dedicated to strengthening HIV testing uptake among YMSM,2–6 fewer resources have been expended to ensure that counseling, testing, and referral (CTR) services are developmentally and culturally tailored and responsive to the needs of YMSM.7–9 This is particularly problematic as previous research10,11 has noted that clients may feel more motivated to engage in repeat HIV testing or to adopt other prevention efforts [eg, pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP)] when agencies offer high-quality services and circumvent structural barriers (eg, medical mistrust; stigma).12–14 At present, however, there are no systematic assessments to evaluate the quality of agencies' CTR services, nor an understanding of the how YMSM clients perceive and react to the quality of testing services.

Quality assurance (QA) indicators offer agencies opportunities to systematically evaluate their service performance, examine whether staff are implementing protocols with fidelity, and identify actionable improvement strategies and/or disseminate models of “best practice” to other agencies.15 Mystery shopping11,16 is an action-oriented strategy whereby organizations can understand their performance across a systematically obtained set of service indicators, as rated by the client base they intend to serve. Bauermeister et al11 used a youth-driven mystery shopper assessment of 46 HIV/Sexually Transmitted Infection (STI) testing clinics in the Detroit metropolitan area. YMSM were trained as mystery shoppers and in the use of a psychometrically-sound QA instrument examining clinics' environmental characteristics, compliance with federal and state CTR protocols, and performance during testing and counseling. QA data showed variability in the depth and quality of CTR services. For example, although mystery shoppers reported overall satisfaction with the environmental characteristics of the clinics, they noted that test counselors infrequently and inconsistently ascertained YMSM's motivations for testing, discussed risk reduction strategies, and/or helped set actionable prevention goals. These findings underscore the need for QA strategies to identify opportunities to strengthen the delivery of culturally competent HIV/STI testing services for YMSM.

As part of the NIH Adolescent Medicine Trials Network for HIV/AIDS Interventions [Adolescent Trials Network (ATN)], we deployed mystery shopping in 3 cities with high HIV incidence (Philadelphia, Atlanta, and Houston) to characterize the quality of HIV testing services available to YMSM living in these cities. Our study had 3 objectives. First, we examined the proportion of HIV testing locations that offered accessible HIV prevention services to YMSM, as characterized by the sites' availability of free, rapid HIV testing and walk-in appointments. We then recruited and trained YMSM to serve as mystery shoppers and visit identified HIV testing locations in these 3 cities. Finally, we examined sites' QA domains and tested whether differences emerged across cities.

METHODS

Identification of HIV Testing Locations in Each City

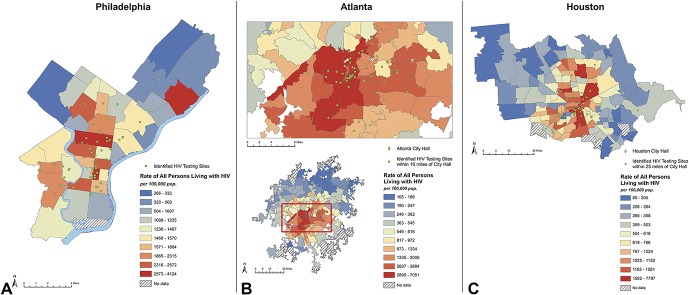

Using AIDSVu.org and Google, we created a list of sites in each city that offered free, rapid HIV testing (Fig. 1). We recorded specified clinic information for any testing sites that had websites, then we called each site using a standardized phone script to collect information about hours, location, and availability and characteristics (ie, cost) of HIV and STI testing services. Discrepancies were frequent between online and staff-provided information. We excluded health systems (eg, hospitals) from our lists as they do not allow rapid, walk-in HIV testing. When the list of verified sites was complete, we mailed each site a standardized letter with information about the study detailing the proposed mystery shopping and offered an opportunity to decline participation in the study. In Atlanta, one testing site contacted study staff to request their site be excluded from mystery shopping. No sites in Philadelphia or Houston declined participation.

FIGURE 1.

HIV testing sites and HIV prevalence per 100,000 people in (A) Philadelphia, (B) Atlanta, and (C) Houston.

Mystery Shopper Recruitment

Recruitment Strategy

Mystery shopper recruitment was managed by the local ATN site in each city. Each ATN site recruited participants using various methods, including (1) contacting former research participants who had consented to be contacted for future studies; (2) posting study information on the ATN site's Facebook page; (3) reaching out to community organizations that serve YMSM; (4) partnering with Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer (LGBTQ) groups at local schools and universities; (5) attending local events for YMSM or LGBTQ youth; and (6) word-of-mouth.

Screening

Interested individuals completed an online screener survey to determine eligibility. Inclusion criteria were: (1) assigned male at birth; (2) currently identify as male; (3) aged 18–24 years (inclusive) at time of screening; (4) self-report as HIV-negative; (5) speak and read English; (6) report same-sex attraction; (7) reside in Philadelphia, Atlanta, or Houston; and 8) able to attend testing sites.

Enrollment and Consent of Mystery Shoppers

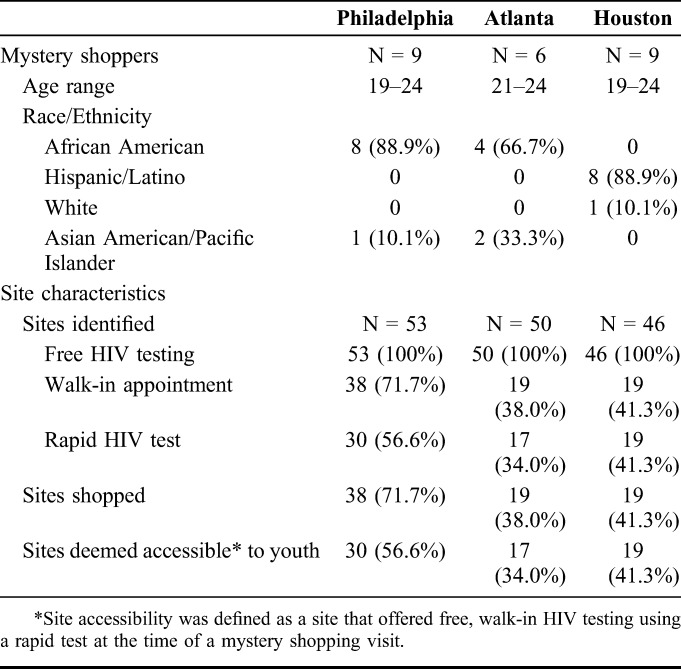

ATN site staff contacted eligible applicants to arrange an in-person meeting to provide additional study details and complete the informed consent. At the meeting, ATN site staff reviewed participation details and answered any questions. Staff then consented the participant and asked about their availability for the half-day mystery shopper training. Demographic characteristics for the mystery shoppers across the 3 cities are detailed in Table 1. Study procedures were reviewed by the University of North Carolina's Institutional Review Board, as the IRB of Record. Reliance agreements across the partnering institutions were secured.

TABLE 1.

HIV Testing Sites' and Mystery Shopper Participants' Characteristics by ATN City

Mystery Shopper Training

Before mystery shopping began, study staff led a half-day in-person training at the ATN site. The training included basic information about HIV, protocol for an HIV test, PrEP information, any state- or city-specific HIV testing rules, and an example of what a high-quality testing experience would include. In addition, mystery shoppers were shown videos of simulated testing visits, followed by a discussion of what was done well and what could be improved in each. Study staff also performed role-plays of different testing scenarios and patient–provider interactions to elicit additional conversation and for mystery shoppers to practice using the site assessment survey. Mystery shoppers were instructed to be honest about their sexual behaviors during their visits and to avoid creating false personas. This guideline was informed by previous research, suggesting that providers tend to alter their dynamics with patients during standardized patient assessment.11,16,17 By providing an honest narrative, shoppers were able to avoid arousing suspicion or creating confusion that may lead to embarrassment or incongruous stories. The training was designed to enhance shoppers' self-efficacy for refusing medical procedures and/or asserting their rights to providers. The training concluded with a comprehensive explanation of mystery shopping visit procedures from scheduling to completion of the site assessment survey. Participants were paid $100 for the 4-hour training.

Site Visits

Previsit Procedures

Before each visit, ATN site staff determined which site the mystery shopper would visit (site visits were randomized by day) and gave the shopper a study iPhone. Mystery shoppers used the phone to request an Uber ride to the testing site using the study's Uber for Business account. Study phones protected mystery shoppers' privacy and Uber facilitated easy transport to and from the testing sites. Mystery shoppers were instructed to use the study phone to contact ATN site staff if they encountered any issues over the course of their testing site visit. Some shoppers scheduled a second site visit at the conclusion of their first site visit. After the shopper's last testing site visit of the day, he would return to the ATN site using Uber.

Visit Procedures

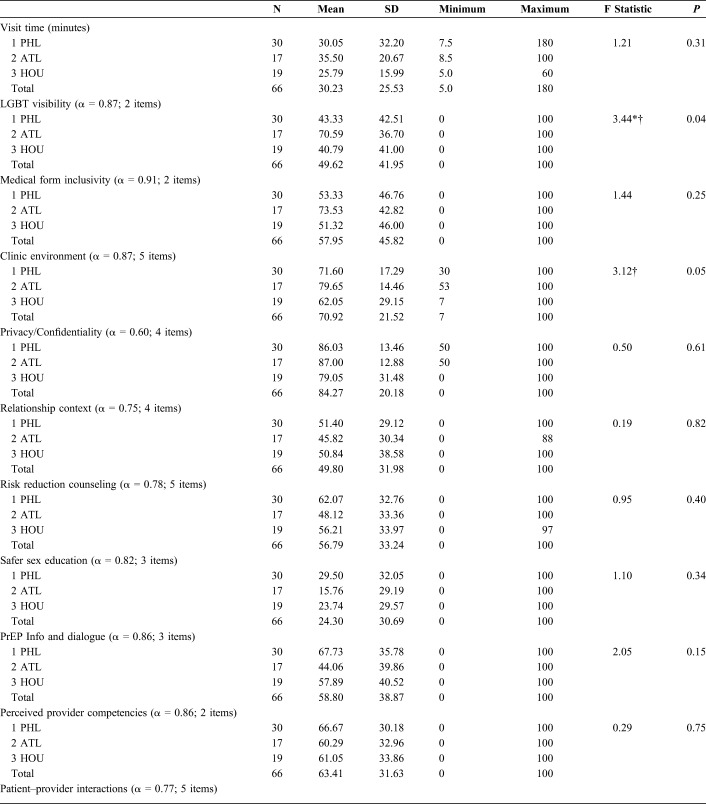

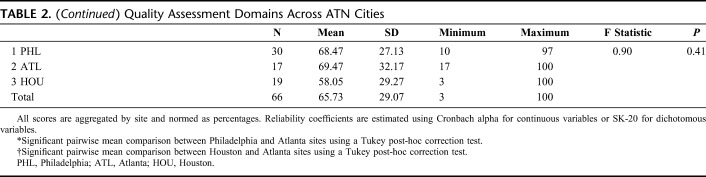

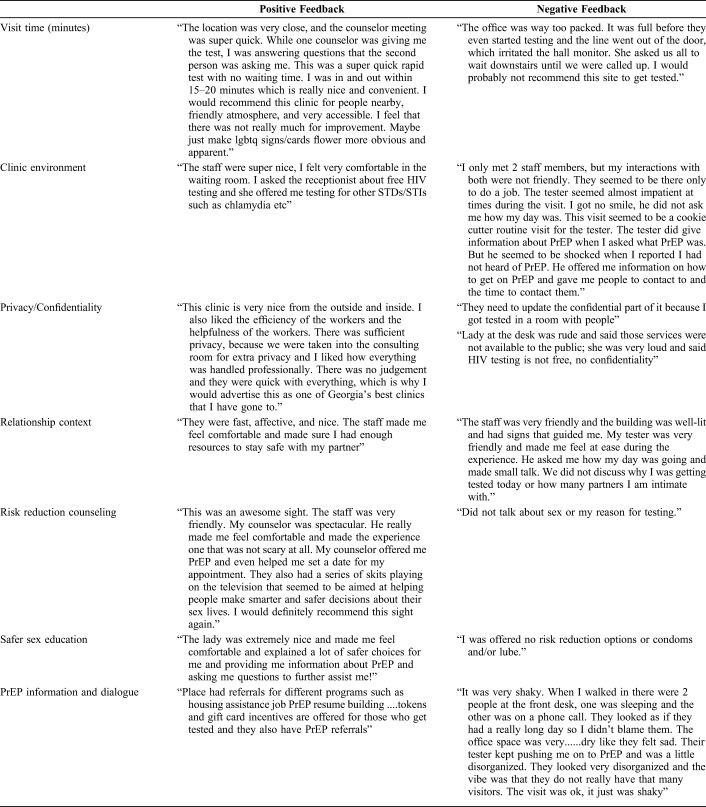

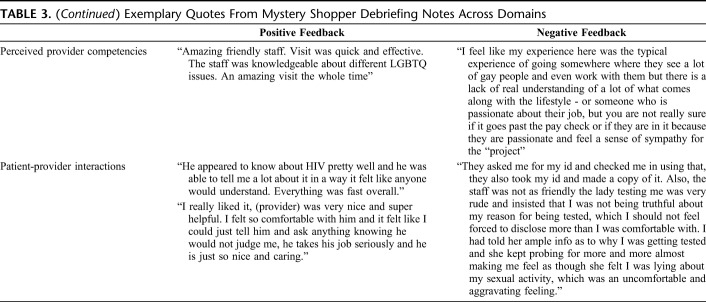

Each testing site was shopped twice at varying times (eg, morning versus afternoon or evening) and days (weekdays vs. weekends when applicable) by 2 different mystery shoppers. Shoppers arrived at their assigned testing site and asked for a free rapid HIV test. Shoppers completed the previously validated site assessment survey on the study phone immediately after the visit or on a computer upon their return to the ATN site. The assessment survey collected information on the duration of the visit, visibility of LGBTQ symbols and printed materials (eg, rainbow flag; magazines; and flyers), the clinic environment, and how well privacy and confidentiality were maintained. Shoppers also evaluated the providers' discussions regarding relationship context, testing and counseling assessment, safer sex recommendations, and PrEP-related discussions (Table 2). At the end of each assessment survey, shoppers were given the opportunity to provide an overall qualitative impression of their experience at the site. These open text fields enabled the shopper to describe how they felt about the site and the provider; anything notable that had occurred over the course of the visit, be it positive or negative; and any other information deemed pertinent to the experience that was not already captured by the quantitative assessment. We offer illustrative quotes from shoppers across QA domains in Table 3.

TABLE 2.

Quality Assessment Domains Across ATN Cities

TABLE 3.

Exemplary Quotes From Mystery Shopper Debriefing Notes Across Domains

Upon return to the ATN sites after a testing visit, mystery shoppers returned the study phone and a staff member conducted a short debriefing meeting. The informal interview served to capture any details of the visit that may have been missed in the site assessment survey, to help ensure any untoward events were discussed, and to offer any resources that may assist the mystery shopper. If possible, staff scheduled additional site visits with the shopper at the conclusion of the debriefing session. Alternatively, staff and participants would communicate via text or email to schedule additional site visits. After this quick conversation, participants received a $50 incentive for their completed visit. Shoppers could complete a maximum of 10 visits for this study.

Once mystery shopping was completed in each city, we mailed each site their personalized results, which included a summary of their pooled results on each of the QA domains assessed and their scores relative to other sites visited in the same city. The report also included mystery shoppers' reflections, as noted in their evaluation surveys, and edited debriefing notes.

Data Analytic Strategy

Using the pre-established domains, we computed site composite score using the pooled scores between the 2 shoppers. Pooled scores are presented to reduce potential selection bias and confounding based on whether the same or a different provider interacted with shoppers at either site visit, and to account for the variability across shoppers. For ease interpretability across domains, we standardized the pooled average scores into percentiles. We used one-way analysis of variances with a Welch test correction to avoid assuming that the variance across scores would be comparable across the 3 cities. When appropriate, Tukey pair-wise comparisons were used to estimate differences between sites.

RESULTS

Philadelphia

We originally identified 53 sites within the jurisdiction of the Philadelphia Department of Public Health (Table 1). During verification of sites, we excluded 15 sites, because they did not provide walk-in appointments, did not offer rapid HIV testing at their location, or were part of a health system. Thus, our sampling frame for mystery shopping in Philadelphia was 38 sites. Thirty of the 38 sites visited were deemed youth accessible (ie, site offered free, walk-in HIV testing using a rapid test at the time of a mystery shopping visit) upon completion of the mystery shopping procedures.

Philadelphia site visits averaged 30 minutes (SD = 32.2) and were perceived to be welcoming and friendly environments (71.6%). YMSM perceived most sites respected their privacy and confidentiality (86.0%). YMSM noted some deficiencies in providers' competencies in working with sexual minority youth (66.7%) and comfort during the interaction (68.5%). HIV testing sites were rated poorly by YMSM on LGBT visibility (43.3%) and inclusivity on medical forms (53.3%). During the risk assessment, Philadelphia sites on average did not discuss YMSM's relationship context (51.4%), nor provide risk reduction counseling (62.1%) or safer sex education (29.5%). Delivery of PrEP information and counseling was also inconsistent across sites (67.7%).

Atlanta

We originally identified 50 sites within a 25-mile radius from Atlanta City Hall (Table 1). During verification of sites, we excluded 31 sites, as most of the HIV testing sites were embedded within health systems, required a fee to test for HIV, did not offer rapid HIV testing, and/or did not offer walk-in appointments. Thus, our sampling frame for mystery shopping in Atlanta was 19 sites. Seventeen of these 19 sites visited were deemed youth accessible (ie, site offered free, walk-in HIV testing using a rapid test at the time of a mystery shopping visit) on completion of the mystery shopping procedures.

Site visits in Atlanta averaged 35.5 minutes (SD = 20.7). Atlanta sites scored highest in YMSM's perceptions that sites were welcoming and friendly environments (79.7%), with their scores being significantly higher than Houston sites (Table 2). YMSM perceived most sites respected their privacy and confidentiality (87.0%). YMSM noted some deficiencies in providers' competencies in working with sexual minority youth (60.3%) and comfort during the interaction (69.5%). Compared with the other 2 cities (Table 2), Atlanta fared better in HIV testing sites' LGBT visibility (70.6%). Atlanta sites were also perceived to have more inclusive medical forms (73.5%). During risk assessments, however, Atlanta sites did not regularly discuss YMSM's relationship context (45.8%), nor provide risk reduction counseling (48.1%) or safer sex education (15.8%). Delivery of PrEP information and counseling was also inconsistent across sites (44.1%).

Houston

We originally identified 46 sites within a 25-mile radius from Houston City Hall (Table 1). During verification of sites, we excluded 27 sites because they required a fee to test for HIV, did not offer rapid HIV testing, were a part of a health system, and/or did not offer walk-in appointments. Thus, our sampling frame for mystery shopping in Houston was 19 sites; all of these sites were deemed accessible to youth after their mystery shopping assessment.

Houston site visits averaged 25 minutes (SD = 16.0), were perceived to be somewhat welcoming and friendly (62.1%), and respectful of YMSM's privacy and confidentiality (79.5%). YMSM noted some deficiencies in providers' competencies in working with sexual minority youth (61.1%) and comfort during the interaction (58.1%). HIV testing sites were rated as underperforming on LGBT visibility (40.8%) and inclusivity on medical forms (51.3%). During risk assessments, sites on average did not discuss YMSM's relationship context (50.8%), nor provide risk reduction counseling (56.2%) or safer sex education (23.7%). Delivery of PrEP information and counseling was also inconsistent across sites (57.9%).

DISCUSSION

Delivery of quality culturally and developmentally appropriate services may help YMSM access and navigate complex health care systems and achieve ongoing engagement with HIV prevention or care services. As an HIV test is often an individual's first experience with clinical HIV prevention services (eg, PrEP), it is important that this event is a positive experience, as a negative experience may deter future testing or engagement in care. At present, however, limited research has explored the quality of HIV/STI testing services. In the absence of such data, ensuring that HIV testing services offer developmentally and culturally competent care for YMSM remains a challenge. Therefore, this study's systematic collection of YMSM's experiences when seeking HIV testing and prevention services in 3 large metropolitan areas is an important step toward improving these services for youth.

Although national campaigns and local efforts have sought to compile and share online HIV testing site locators,18,19 this study found that actual service availability at testing sites differed significantly from the service information provided in online resource directories. Given that HIV testing is one of the 4 pillars of the Ending the HIV Epidemic in the United States by 2030 initiative,1 these service availability discrepancies are particularly concerning as current guidelines6 call for YMSM to test for HIV every 6 months. It remains a priority to increase funding allocations to support the availability of agencies that provide free, same-day rapid HIV testing in highly-affected areas identified in the Ending the HIV Epidemic in the United States by 2030 initiative.

Beyond increasing the availability of free, rapid, walk-in HIV testing locations across the country, it is paramount that efforts also strengthen the current delivery of CTR for YMSM. Encouraging HIV/STI testing among YMSM within public health campaigns may be less effective if HIV testing sites' services are not culturally competent to this population.8,20–22 Overall, YMSM participating in the mystery shopping assessment found large variability in clinics' efforts to showcase LGBT-friendly materials and offer LGBT-inclusive language on medical forms. This variability differed by city, with YMSM in Atlanta reporting greater visibility of LGBT-inclusive materials than those in Philadelphia or Houston. Given that previous research has recommended the integration of LGBT-affirming materials as a strategy to encourage comfort for sexual and gender minority populations within medical settings,21–23 renewed efforts focused on creating spaces that are welcoming to LGBT clients may be warranted.

The breadth and quality of the CTR sessions were also found to vary across agencies in the 3 cities. Although most YMSM felt that sites maintained their privacy and confidentiality during visits, we were surprised by providers' limited assessments of YMSM's relationship contexts and discussions of safer sex education and PrEP. Moreover, YMSM perceived that providers could improve the quality of their interactions with them by offering risk reduction counseling, avoiding judgments during sexual risk screenings, and having greater awareness of the needs and experiences of YMSM clients. Taken together, these findings highlight the need to strengthen agencies' delivery of culturally competent care through systems-level interventions.15 The Health Access Initiative, for example, is a systems-level intervention that includes cultural responsiveness training for medical, clerical, programmatic, and administrative staff, as well as technical assistance to improve policies and protocols related to LGBTQ + youth's health care needs.24,25 At 6-month follow-up, clinics who received Health Access Initiative training reported changes in their infrastructure (eg, changes to medical forms and access to gender-inclusive bathrooms) and improvements in staff knowledge, attitudes, and practices when working with young sexual and gender minority clients. If we are to achieve the Ending the HIV Epidemic in the United States by 2030 initiative goals, investment in system-level interventions and strategies will be necessary to optimize HIV prevention and care delivery for YMSM.

This study has several limitations worth noting. Although we sought to diversify the data obtained within each testing site by having 2 mystery shoppers visit each site on different days and times, site assessments are unlikely to reflect all providers at each testing site. Second, our study does not seek to be generalizable to all testing sites across the United States, as each city may have a unique set of characteristics that influence the availability and quality of testing sites. However, our QA evaluation tool seemed to work well across 3 cities and had strong psychometric properties across the different domains. Third, we excluded health systems (eg, emergency rooms in hospitals) from our mystery shopping procedures, which may not reflect the full landscape of HIV testing locations in a city. Finally, the cross-sectional design of our study limits our ability to make causal inferences about the data reported here. Future research examining the validity of the tool in predicting Young Gay and Bisexual Men's likelihood to repeat test and/or seek treatment in certain locations is warranted.

Despite these limitations, the findings of this study suggest that the implementation of youth-driven QA systems for HIV testing services is feasible and may offer opportunities to strengthen the delivery of culturally competent HIV testing practices. Achieving high rates of routine HIV testing among YMSM is likely a product of both demand and supply. Rather than assuming that low HIV testing rates among some YMSM may be because of limited motivation to engage in HIV prevention (demand), our findings underscore the importance of considering whether site characteristics and provider interactions are also influencing YMSM's testing motivations and behaviors (supply). Although mystery shopping is a novel strategy in the HIV testing context, we recognize that government agencies and community groups may have challenges implementing this strategy. Nevertheless, our developed indicators may be used by HIV testing sites and/or funders to assess site performance. For example, agencies could integrate the QA evaluation tool in their exit satisfaction surveys and review them quarterly to prioritize areas of need with their staff.16 Similarly, funders could ask agencies to collect these data and include them in their annual reports, use these data to incentivize sites with evidence of strong care, and/or provide technical assistance to sites that are underperforming. Future research examining the implementation of these systemic strategies and their effect on YMSM's testing and engagement in care is warranted if we are to achieve the ambitious goals set by the Ending the HIV Epidemic in the United States by 2030 initiative.

Footnotes

Supported by the National Institutes of Health Adolescent Medicine Trials Network for HIV/AIDS Interventions and the University of North Carolina/Emory Center for Innovative Technology (U19HD089881). This work was also supported by the Center for AIDS Research at the University of Pennsylvania (P30 AI 045008), Emory University (P30AI050409), the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (P30AI50410), the Penn Center for AIDS Research (CFAR) (P30 AI 045008 - Ronald Collman, PI), the Penn Mental Health AIDS Research Center (PMHARC) (P30 MH 097488 - Dwight Evans, PI) and the CFAR Social & Behavioral Science Research Network National Scientific Meeting (SBSRN) (R13 HD 074468 - Michael Blank, PI). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not represent the official views of the funding agencies.

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1.Fauci AS, Redfield RR, Sigounas G, et al. Ending the HIV epidemic: a plan for the United States. JAMA. 2019;321:844–845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goldenberg T, Stephenson R, Bauermeister J. Community stigma, internalized homonegativity, enacted stigma, and HIV testing among young men who have sex with men. J Community Psychol. 2018;46:515–528. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bauermeister JA, Golinkoff JM, Horvath KJ, et al. A multilevel tailored web app-based intervention for linking young men who have sex with men to quality care (get connected): protocol for a randomized controlled trial. JMIR Res Protoc. 2018;7:e10444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Merchant RC, Clark MA, Liu T, et al. Comparison of home-based oral fluid rapid HIV self-testing versus mail-in blood sample collection or medical/community HIV testing by young adult black, hispanic, and white MSM: results from a randomized trial. AIDS Behav. 2018;22:337–346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liu Y, Silenzio VMB, Nash R, et al. Suboptimal recent and regular HIV testing among black men who have sex with men in the United States: implications from a meta-analysis. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2019;81:125–133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.DiNenno EA, Prejean J, Irwin K, et al. Recommendations for HIV screening of gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men - United States, 2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66:830–832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Miller RL, Janulis PF, Reed SJ, et al. Creating youth-supportive communities: outcomes from the connect-to-protect(R) (C2P) structural change approach to youth HIV prevention. J Youth Adolescence. 2016;45:301–315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tanner AE, Philbin MM, Duval A, et al. “Youth friendly” clinics: considerations for linking and engaging HIV-infected adolescents into care. AIDS Care. 2014;26:199–205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Philbin MM, Tanner AE, DuVal A, et al. Factors affecting linkage to care and engagement in care for newly diagnosed HIV-positive adolescents within fifteen adolescent medicine clinics in the United States. AIDS Behav. 2014;18:1501–1510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mustanski BS, Newcomb ME, Du Bois SN, et al. HIV in young men who have sex with men: a review of epidemiology, risk and protective factors, and interventions. J Sex Res. 2011;48:218–253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bauermeister JA, Pingel ES, Jadwin-Cakmak L, et al. The use of mystery shopping for quality assurance evaluations of HIV/STI testing sites offering services to young gay and bisexual men. AIDS Behav. 2015;19:1919–1927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Turan B, Hatcher AM, Weiser SD, et al. Framing mechanisms linking HIV-related stigma, adherence to treatment, and health outcomes. Am J Public Health. 2017;107:863–869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wood S, Gross R, Shea JA, et al. Barriers and facilitators of PrEP adherence for young men and transgender women of color. AIDS Behav. 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Meanley S, Gale A, Harmell C, et al. The role of provider interactions on comprehensive sexual healthcare among young men who have sex with men. AIDS Educ Prev. 2015;27:15–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bauermeister JA, Tross S, Ehrhardt AA. A review of HIV/AIDS system-level interventions. AIDS Behav. 2009;13:430–448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Granatino R, Verkamp J, Stephen Parker RS. The use of secret shopping as a method of increasing engagement in the healthcare industry: a case study. Int J Healthc Manag. 2013;6:114–121. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rhodes K. Taking the mystery out of “mystery shopper” studies. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:484–486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Muessig KE, Nekkanti M, Bauermeister J, et al. A systematic review of recent smartphone, Internet and Web 2.0 interventions to address the HIV continuum of care. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2015;12:173–190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.LeGrand S, Muessig KE, Horvath KJ, et al. Using technology to support HIV self-testing among MSM. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2017;12:425–431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Knight RE, Shoveller JA, Carson AM, et al. Examining clinicians' experiences providing sexual health services for LGBTQ youth: considering social and structural determinants of health in clinical practice. Health Educ Res. 2014;29:662–670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Levy ME, Wilton L, Phillips G, et al. Understanding structural barriers to accessing HIV testing and prevention services among black men who have sex with men (BMSM) in the United States. AIDS Behav. 2014;18:972–996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wilkerson JM, Rybicki S, Barber CA, et al. Creating a culturally competent clinical environment for LGBT patients. J Gay Lesbian Soc Serv. 2011;23:376–394. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sevelius JM, Patouhas E, Keatley JG, et al. Barriers and facilitators to engagement and retention in care among transgender women living with human immunodeficiency virus. Ann Behav Med. 2014;47:5–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kazaleh Sirdenis T, Harper GW, Carrillo M, et al. Toward sexual health equity for gay, bisexual and transgender youth: an inter-generational collaborative multi-sector partnerships approach to structural change. Health Educ Behav. In press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Bauermeister JA, Pingel ES, Sirdenis TK, et al. Ensuring community participation during program planning: lessons learned during the development of a HIV/STI program for young sexual and gender minorities. Am J Community Psychol. 2017;60:215–228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]