Abstract

Hypothalamic GnRH (luteinizing hormone–releasing hormone) neurons are crucial for the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal (HPG) axis, which regulates mammalian fertility. Insufficient GnRH disrupts the HPG axis and is often associated with the genetic condition idiopathic hypogonadotropic hypogonadism (IHH). The homeodomain protein sine oculis–related homeobox 6 (Six6) is required for the development of GnRH neurons. Although it is known that Six6 is specifically expressed within a more mature GnRH neuronal cell line and that overexpression of Six6 induces GnRH transcription in these cells, the direct role of Six6 within the GnRH neuron in vivo is unknown. Here we find that global Six6 knockout (KO) embryos show apoptosis of GnRH neurons beginning at embryonic day 14.5 with 90% loss of GnRH neurons by postnatal day 1. We sought to determine whether the hypogonadism and infertility reported in the Six6KO mice are generated via actions within the GnRH neuron in vivo by creating a Six6-flox mouse and crossing it with the LHRHcre mouse. Loss of Six6 specifically within the GnRH neuron abolished GnRH expression in ∼0% of GnRH neurons. We further demonstrated that deletion of Six6 only within the GnRH neuron leads to infertility, hypogonadism, hypogonadotropism, and delayed puberty. We conclude that Six6 plays distinct roles in maintaining fertility in the GnRH neuron vs in the migratory environment of the GnRH neuron by maintaining expression of GnRH and survival of GnRH neurons, respectively. These results increase knowledge of the role of Six6 in the brain and may offer insight into the mechanism of IHH.

Mammalian reproduction is mediated by the pulsatile release of GnRH from GnRH neurons. GnRH neurons are key to the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal (HPG) axis, which controls a multitude of physiological functions including reproduction, menstruation, pregnancy, and menopause. As part of this axis, GnRH is synthesized in the hypothalamus and then stimulates the release of LH and FSH from the anterior pituitary. These hormones, in turn, act on the gonads to produce testosterone, estrogen, and progesterone in the process of gametogenesis (1, 2). During development, GnRH neurons complete a long migratory journey (3). They originate in the olfactory placode at embryonic day (e) 11.5 and migrate across the cribriform plate and through the basal forebrain before arriving in the presumptive hypothalamus. Once in the hypothalamus, GnRH neurons extend their axons to the median eminence where secreted GnRH enters the hypophyseal portal system and reaches the pituitary (4).

Errors in GnRH secretion from the GnRH neuron, migration of the GnRH neuron, or development of the GnRH neuron can result in levels of GnRH that are insufficient to properly stimulate the HPG axis. This can result in the condition idiopathic hypogonadotropic hypogonadism (IHH), which is characterized by varying degrees of impaired fertility (5). Additionally, insufficient GnRH can result in the subtype of IHH, Kallmann syndrome, that is characterized by impaired fertility paired with anosmia (6). These conditions have been linked to numerous genetic mutations; however, >50% of cases of IHH have unknown genetic origins (7).

Several genes responsible for ventral forebrain development have been associated with IHH. Developmental errors in the olfactory placode and ventral forebrain can produce IHH because their abnormal development and function is prone to disrupt the development of GnRH neurons and their migration from the olfactory placode to the hypothalamus (8). Studies conducted in homozygous, heterozygous, and tissue-specific knockout (KO) mouse models have shown that loss of certain homeodomain proteins, including Vax1, Otx2, Dlx1/2, and Six3, can result in significant reductions of GnRH, and therefore various degrees of subfertility and infertility have been reported (9–13).

One homeodomain protein that we have shown plays an essential role in the development of GnRH neurons and regulation of fertility is sine oculis–related homeobox 6 (Six6) (11). Using a global KO mouse model, Six6 has been identified as a potential candidate in polygenic IHH (11). Six6 is a highly conserved homeobox gene required for proper forebrain and eye development (14, 15). The timing and spatial expression pattern of Six6 overlaps with the emergence, migration, and development of GnRH neurons (16). Additionally, overexpression of Six6 induces GnRH transcription in GT1-7 neuronal cells via binding to evolutionarily conserved ATTA sites located within the GnRH proximal promoter (11). The KO mouse model, Six6KO, showed that complete loss of Six6 results in a 90% reduction in GnRH neurons as detected by GnRH immunohistochemistry, leading to infertility (11). Male Six6KO mice showed reduced fecundity and lower FSH; however, LH, testosterone, and spermatogenesis were unaffected. Female reproductive physiology was more drastically affected by total loss of Six6, with female mice showing almost complete infertility, noncyclic estrous cycles, reduced ovary size, and fewer corpora lutea (11).

Six6 is expressed throughout the regions through which GnRH neurons develop and migrate, and within the GnRH neuron. Therefore, it is unclear whether GnRH is deficient due to actions of SIX6 within the GnRH neuron, or whether SIX6 is essential for the survival/migration of the GnRH neuron through actions in the migratory environment of the GnRH neuron. This study shows that Six6 plays an essential role within the GnRH neuron in maintaining expression of GnRH, in that the loss of Six6 solely from GnRH neurons results in infertility and reproductive impairment.

Methods

Mouse lines and animal housing

All animal procedures were performed in accordance with the University of California, San Diego, Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee regulations (IACUC protocol S00261). Mice were group-housed with approximately four mice per cage on a 12-hour light, 12-hour dark cycle (on 6:00 am, off 6:00 pm), with ad libitum water and chow [Global Irradiated Chow 2920X (Teklad laboratory animal diets); Envigo]. All mice were kept on a C57BL/6J mouse background. Six6KO (17) mice were generated as previously described (18) and were kindly provided by Dr. Xue Li (Children’s Hospital of Boston, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA). Six6flox mice were generated from a Six6 European Conditional Mouse Mutagenesis Program (EUCOMM) KO first construct (targeting vector ETPG00270_Y_5_D06; backbone L3L4_pD223_DTA_T_spec; Cassette Ifitm2_intron_L1L2_GT2_LF2A_LacZ_BetactP_neo). Because the Six6 gene has only two exons and thus only one intron, an artificial intron was inserted into exon 1 to contain the flippase recombinase target (FRT)–flanked selection cassette followed by the 5′ LoxP site. The intron was derived from the Ifitm2 gene and remains in the final Six6 exon 1 in the floxed mouse, where it contains the remaining single FRT element and the 5′ LoxP site. The plasmid was introduced by electroporation into male C57BL/6J mouse embryonic stem cells, selected by using G418 (selection against vector insertion was diphtheria toxin A on the backbone of the plasmid), and screened for homologous recombined cells by PCR. A homologous recombined clone of mouse embryonic C57BL/6J stem cells was then injected into albino C57BL/6J blastocysts to produce chimeric mice. These were screened for percentage chimerism and correct recombination. The highest percentage male chimeric mice were bred to C57BL/6J females to create heterozygous Six6flox mice. Once confirmed as correctly floxed for Six6, they were crossed with a flpase mouse (19, 20) to remove the selection cassette, leaving only one FRT site and the 5′ LoxP site in the artificial intron and the 3′ LoxP site in the original intron between exons 1 and 2 to create the Six6flox conditional KO allele. LoxP sites flanked most of exon 1 of the Six6 gene. Floxed homozygous mice evidenced no previously described phenotypes, indicating that the artificial intron was correctly spliced. Six6flox genotyping was performed with Six6WT forward: 5′GAAGCCCTTAACAAGAATGAGTCGG3′; Six6flox forward: 5′CTTCGGAATAGGAACTTCGGTT 3′, reverse: 5′CTTTGAATTTGGGTCCCTGG 3′. Primers to test for germline recombination are forward: 5′AAGACAGACTGCATTCCCAGC3′; reverse: 5′AGACTCACTGCTTCAAGGAGC3′. These mice were then mated to LHRHcre (21, 22) mice for conditional removal of the majority of Six6 exon 1 within the GnRH neurons. For lineage tracing, RosatdTomato (23, 24) and RosaLacz (25) reporter mice were used and mated to Six6flox and LHRHcre mice to create the Six6flox/flox/RosaLacZ/LHRHcre and Six6KO/RosatdTomato/GnRHcre lines (Gnrhcre) (26, 27). The same approach was used for lineage tracing in the Six6KO mouse model. Germline deleted mice exhibited the same phenotype as the previously studied Six6KO mouse (18), demonstrating the effectiveness of deleting exon 1 on removing Six6 (data not shown). Mice were euthanized by CO2 or isoflurane (Vet One, Meridian) overdose. Controls used for the Six6KO line were wild-type (WT) mice; controls for the Six6flox/flox/LHRHcre mice were Six6flox/flox mice, controls for the Six6flox/flox/RosaLacZ/LHRHcre mice were RosaLacZ/LHRHcre mice; controls for the Six6KO/RosatdTomato/GnRHcre mice were RosatdTomato/GnRHcre mice.

Collection of tissue and histology

Ovaries and uteri from diestrus females and testes from males were dissected and weighed from animals 3 months of age. Diestrus ovaries, brains, olfactory bulbs, embryos, and testes were fixed for 2 days (∼49 hours) at 4°C in a freshly made mixture of 6:3:1 absolute alcohol: 37% formaldehyde [glacial acetic acid (Fisher F79-4); Thermo Fisher Scientific], then dehydrated in 70% ethanol before paraffin embedding. Sagittal or coronal sections (10 µm) were cut on a microtome and floated onto SuperFrost Plus slides (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Ovaries, testes, brains, and noses were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (Sigma-Aldrich). In ovaries, the number of corpora lutea in a single ovary per mouse was recorded by an investigator blinded to the treatment/genotype.

Determination of pubertal onset and estrous cyclicity

These procedures were described previously in detail (28, 29). To assess estrous cyclicity, vaginal smears were performed daily between 9:00 and 11:00 am for 10 days on 3- to 5-month-old mice by vaginal lavage. A cycle was defined as being from one proestrus smear to the next proestrus smear.

Timed mating

Each Six6flox/flox/LHRHcre or Six6flox/flox female mouse was housed with a Six6flox/flox/LHRHcre or Six6flox/flox male mouse, and vaginal plug formation was monitored. If a plug was present, the day was noted as day 0.5 of pregnancy. Embryos were then collected at day e12.5, e13.5, e15.5, and e17.5.

Fertility assessment

At 12 to 15 weeks of age, virgin Six6flox/flox/LHRHcre and Six6flox/flox mice were housed in pairs. The number of litters and pups produced in 90 days was recorded. Control matings used were Six6flox/flox mice with Six6flox/flox mice.

GnRH-pituitary stimulation tests

For 2 weeks before the hormonal challenge, mice were adapted to handling stress such that they would be unaffected by stress during serial tail blood sampling. Baseline tail blood was collected from female metestrus/diestrus littermates. Ten minutes after an intraperitoneal injection of 1 µg/kg GnRH (Sigma-Aldrich catalog no. L7134) diluted in physiological saline, tail blood was collected again. For kisspeptin challenge, 15 minutes after intraperitoneal injection of 30 nM of kisspeptin (Tocris catalog no. 4243) diluted in physiological saline, tail blood was collected again. The total volume of blood collected did not exceed 100 µL. Blood was collected between 11:00 am and noon and was allowed to clot for 1 hour at room temperature. Blood was then centrifuged at room temperature for 15 minutes at 2600g. Serum was collected and stored at −20°C before Luminex analysis was used to measure LH and FSH. For LH, the lower detection limit was 5.6 pg/mL, the intra-assay coefficient of variation (intra-ACOV) was 13.9%, and the interassay coefficient of variation (inter-ACOV) was 9.12% (n = 15); for FSH, the lower detection limit was 25.3 pg/mL, the intra-ACOV was 12.1%, and the inter-ACOV was 7.2% (n = 17) (MILLIPLEX MAP Mouse Pituitary Magnetic Bead Panel—Endocrine Multiplex Assay, catalog no. MPTMAG-49K, Millipore).

Testosterone analysis

For serum hormone analysis, mice were euthanized by isoflurane overdose and blood was collected from the abdominal aorta between 9:00 and 11:00 am. Blood was allowed to clot for 1 hour at room temperature and then centrifuged (room temperature, 15 minutes, 2600g). Serum was collected and stored at −20°C before RIA analysis for testosterone at the Center for Research in Reproduction, Ligand Assay, and Analysis Core, University of Virginia (Richmond, VA). Samples were run-in singlets. All intra-ACOVs are based on the variance of samples in the standard curve run in duplicate. For testosterone, the lower detection limit was 9.6 ng/dL, the intra-ACOV was 5.4%, and inter-ACOV was 7.8%.

Sperm analysis

Epididymides were collected in M2 media at room temperature (Sigma-Aldrich) (28). One epididymis was cut in half, and sperm were gently expelled by manual pressure. The number of sperm was counted in a hemocytometer 15 minutes after sperm were expelled. To immobilize motile sperm the hemocytometer was placed for 5 minutes on a 55°C heat block.

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) was performed as previously described (28), with the only modification being antigen retrieval by boiling the samples for 15 minutes in 10 mM sodium citrate at a pH 6. Briefly, the primary antibody used was rabbit anti-GnRH [1:1000 (30)] or rabbit anti-GnRH [1:1000 (31)]. All GnRH staining in Six6flox/flox/LHRHcre mice was conducted by using the Immunostar antibody (31), as previous lots used on Six6KO mice were no longer functional for us. GnRH-positive neurons were counted throughout the brain in adults, and throughout the head in embryos. The whole head was counted in embryos, and whole brain was counted in the adult from bregma 1.70 to bregma −2.80 (32). All sections were counted by an investigator blinded to the treatment/genotype. For lineage tracing in the Six6KO mice, tdTomato expression was detected with a rabbit anti–red fluorescent protein (RFP) primary antibody [1:1000 (33)]. For lineage tracing in the Six6flox/flox/LHRHcre mice, β-galactosidase was detected by using anti–β-galactosidase antibody (34).

Cell death analysis

Assays for apoptosis in e14.5 Six6KO mice were performed by using protocols specified in the DeadEnd TUNEL system (Sigma-Aldrich catalog no. 11684795910). Relative levels of cell death between WT and Six6KO mice were determined by counting the number of TUNEL+, GnRH+ cells throughout the head.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed by using the Student t test, Mann-Whitney, or two-way ANOVA, followed by post hoc analysis by Tukey as indicated in figure legends, with P < 0.05 to indicate significance. Prism statistical software (GraphPad) was used for analysis. The n values represent the number of samples included in each group.

Results

Six6 KO leads to GnRH neuron apoptosis

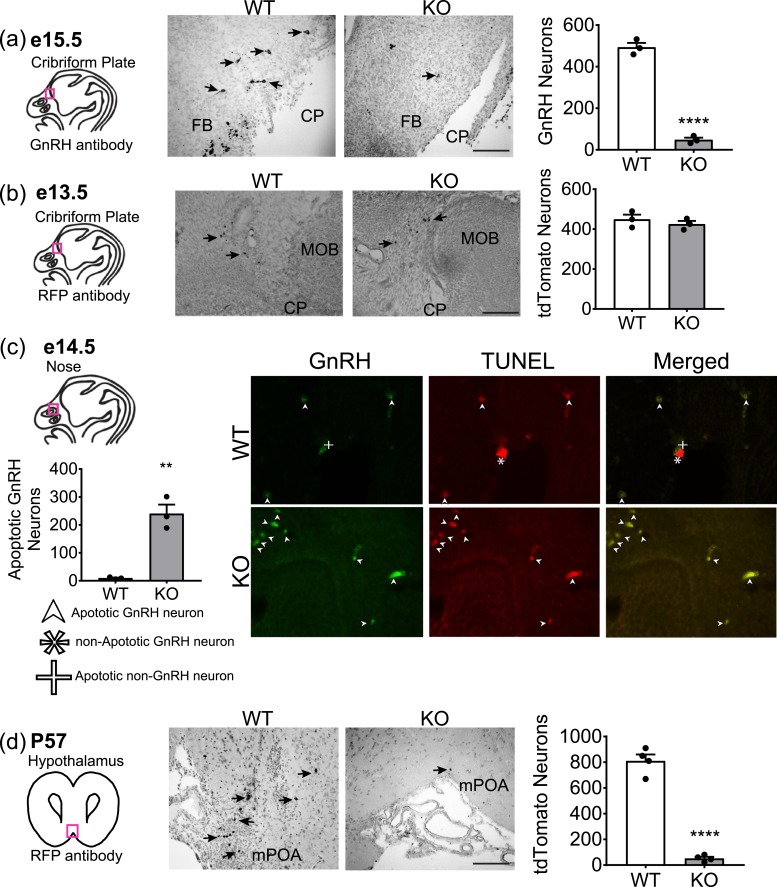

Our previous work has shown that in the global Six6KO mice, GnRH neurons originate normally, with the average number of GnRH neurons at e13.5 being similar in WT and KO mice (11). We also showed that adult Six6KO mice were missing ∼90% of GnRH neurons as detected by GnRH IHC (11). However, it has not yet been determined at what embryonic stage GnRH-expressing neurons in Six6KO mice begin to become undetectable by GnRH staining. Determining when GnRH neurons are lost can provide insight into the developmental mechanisms of Six6 and may indicate which region of the migratory pathway of GnRH is altered. To determine this, we used IHC with an anti-GnRH antibody and counted the number of GnRH neurons in late embryogenesis of Six6KO mice. At e15.5, there is an ∼89% reduction in the number of GnRH neurons, a drastic decrease from the amount present at e13.5, when GnRH neuron numbers were normal in Six6KO (11) [Fig. 1(a)]. The whole head was systematically analyzed for GnRH neurons, and no ectopic localization of the neurons was observed (data not shown).

Figure 1.

GnRH neurons in Six6KO mice are lost to apoptosis at e14.5. Diagrams at left are of embryonic heads or adult coronal sections; red boxes indicate the region shown in the corresponding micrographs. (a) IHC with anti-GnRH antibody at e15.5 in Six6KO mice (n = 3). Scale bar, 20 µm. Arrows indicate GnRH-stained neurons. Graph at right shows numbers of GnRH neurons in the entire head of each embryo, counted blind. (b) IHC with anti–red fluorescent protein (RFP) antibody in Six6KO/RosatdTomato/GnRHcre embryos at e13.5 (n = 4). Scale bar, 20 µm. Graph at right shows average numbers of tdTomato neurons in the entire head of each embryo. (c) Number of GnRH neurons that costain with TUNEL quantified from IHC with anti-GnRH antibody and TUNEL assay in Six6KO mice at e14.5 (n = 3). Arrows indicate apoptotic neurons costained for TUNEL and GnRH. (d) Number of tdTomato+ neurons in the medial preoptic area (mPOA) quantified from IHC with anti-RFP antibody in Six6KO/RosatdTomato/GnRHcre mice at P57 (n = 4). Arrows indicate tdTomato+ neurons. Scale bar, 100 μm. (a–d) Statistical analysis by Student t test as compared with control mice. Abbreviations: CP, cribriform plate; FB, forebrain; MOB, main olfactory bulb. **P < 0.01; ****P < 0.0001.

Thus, Six6 is exerting some effect on or within the GnRH neuron between e13.5 and e15.5, resulting in the loss of GnRH protein expression. However, historically, difficulties have arisen in defining the mechanism of GnRH neuron loss (35, 36). It is possible that loss of Six6 abolishes the expression of GnRH from this neuronal population, making these neurons undetectable using IHC with an anti-GnRH antibody. By that method, it is not possible to distinguish whether GnRH neurons are absent or are failing to express GnRH (37–41). Here, we assessed the mechanism engendering this loss of GnRH neurons using a Six6KO/RosaTdTomato/GnRHcre mouse. Using this mouse, we conducted lineage tracing wherein GnRH neurons express TdTomato within all of the cells targeted by GnRHcre, regardless of continuing GnRH expression. We have previously characterized this GnRHcre promoter and have found that the GnRHcre is expressed at e11.5 onward (42), and allows recombination at e13.5 (36). Assessing the Six6KO/RosaTdTomato/GnRHcre mouse with IHC at e13.5, we show that TdTomato-expressing neurons are generated normally compared with control mice (as was seen in the Six6KO mouse at e13.5) and are successfully labeled with TdTomato [Fig. 1(b)].

We next asked whether the absence of GnRH neurons was the product of apoptosis. This was assessed by using the TUNEL technique to test for DNA fragmentation in cells ex vivo. Analysis was conducted by using double labeling with an antibody for GnRH neurons and the TUNEL assay. In e14.5 mice, only a few apoptotic cells were seen in the WT mice, whereas significantly more were observed in the KO mice [Fig. 1(c)]. The lineage tracing in the adult mouse showed the presence of TdTomato neurons in the RosaTdTomato/GnRHcre mouse, but a loss of ∼96% of GnRH neurons in the Six6KO/RosaTdTomato/GnRHcre mouse [Fig. 1(d)]. Thus, the loss of GnRH neurons in the Six6KO mouse model is not due to a loss of GnRH expression when Six6 is removed from the whole body but rather to loss of GnRH cells themselves. Therefore, the actions of Six6 in the global KO mouse model resulted in apoptosis of GnRH neurons at e15.5, either through effects in the migratory environment of the GnRH neuron or within the GnRH neurons, or both.

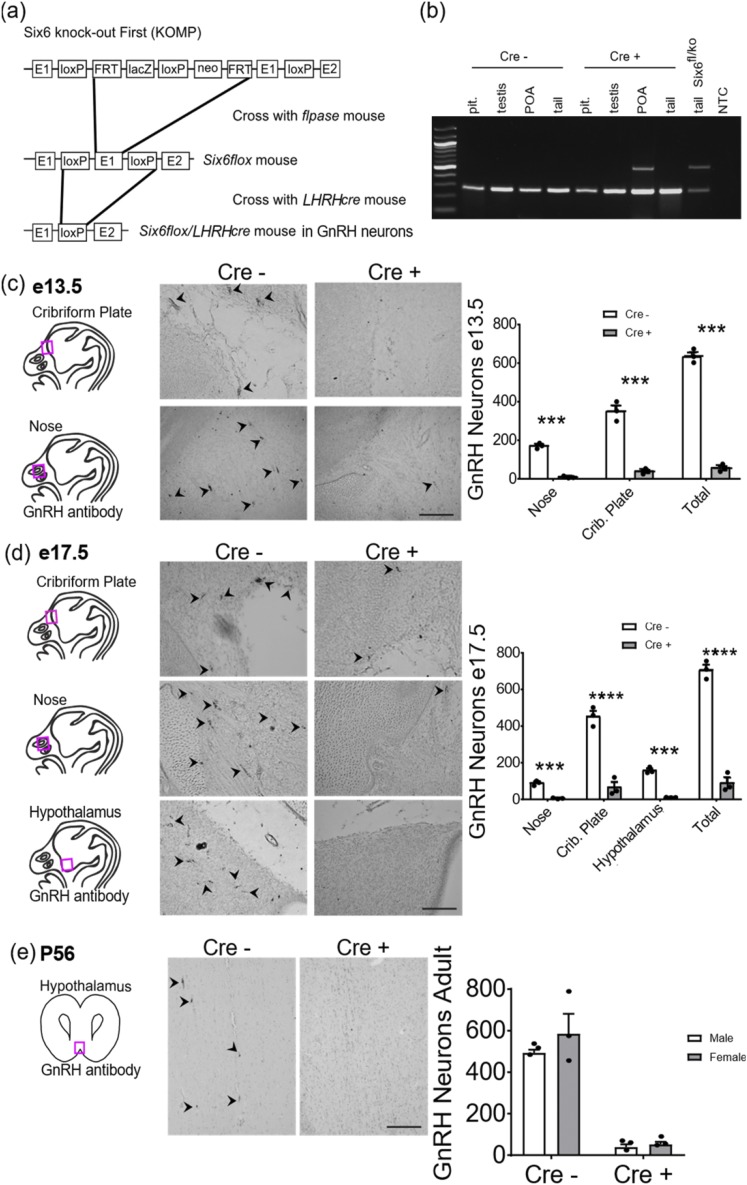

Removal of Six6 specifically within the GnRH neuron decreases detectable GnRH neurons

The loss of GnRH neurons in Six6KO mice at e15.5 may be due to a lack of Six6 expression within GnRH neurons or due to the loss of Six6 expression in the cellular environment through which GnRH neurons migrate. To determine this, we moved from studying the global Six6 knockout, to a Six6flox mouse generated in our laboratory [Fig. 2(a)]. We crossed this mouse with LHRHcre mice [Fig. 2(a)] (22), which we recently found to more accurately target GnRH neurons than the GnRHcre (42), thus allowing for specific deletion of Six6 in GnRH neurons (10, 36, 43, 44). To ensure specificity of the knockout, we validated recombination by the LHRHcre vector in ectopic tissues. LHRHcre recombination is absent from the pituitary and testis and present in the preoptic area [Fig. 2(b)]. In the Six6flox/flox/LHRHcre mouse, the number of GnRH-expressing neurons began declining in early embryogenesis, at e13.5, with significantly fewer GnRH neurons seen in the Six6flox/flox/LHRHcre (Cre+) mouse compared with control (Cre−) a 90% reduction [Fig. 2(b)]. This trend continued into late embryogenesis [Fig. 2(c)] and adulthood [Fig. 2(d)], with Six6flox/flox/LHRHcre mice having 90% fewer GnRH neurons than control mice at e17.5 and P56. Thus, unlike the global Six6KO, selective deletion of the Six6 gene from GnRH neurons results in decreased GnRH neuron number as early as e13.5.

Figure 2.

Loss of Six6 specifically from the GnRH neuron results in a loss of ∼90% of GnRH neurons. (a) Diagram of creation of the Six6flox mouse. A Six6 KO first DNA construct was obtained from EUCOMM, with most of the first exon flanked by LoxP sites and the selection cassette flanked by FRT sites. Breeding with a flpase mouse removed the selection cassette, leaving a floxed exon 1. (b) Representative PCR result from Six6flox/flox/LHRHCre- and Six6flox/flox/LHRHCre+ mice showing that recombination is absent in the pituitary and testis and present in the preoptic area. Floxed band is ∼240 bp, and recombined band is ∼540 bp. (c) Quantification of GnRH neurons at e13.5 in Six6flox/flox/LHRHcre mice from IHC with anti-GnRH antibody (n = 3). White bars are Cre− and gray bars are Cre+ mice. (d) GnRH neurons at e17.5 from IHC with anti-GnRH antibody counted throughout the head (n = 3). White bars are Cre− and gray bars are Cre+ mice. (e) GnRH neurons in the adult at P56 Six6flox/flox/LHRHcre mouse (n = 6). White bars are male and gray bars are female mice. Statistical analysis by two-way ANOVA [there was a statistically significant effect of genotype on GnRH neuron number: F (1, 8) = 99.62, P < 0.0001]. (c–e) Drawings to the left of images represent locations in the head/brain where images were taken. Arrowheads indicate positively stained GnRH neurons. Scale bar, 100 µm. Bar graphs to the right show quantification. Statistical analysis by Student t test as compared with control mice. ***P < 0.001; ****P < 0.0001. Abbreviations: NTC = no template control; Pit. = pituitary; POA = preoptic area.

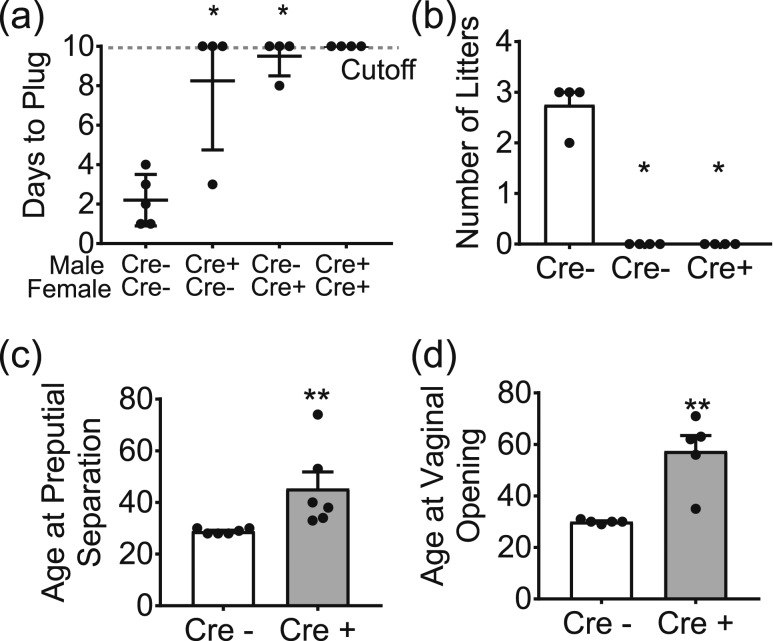

Loss of Six6 within the GnRH neuron causes infertility

The propensity of Six6flox/flox/LHRHcre males and females to copulate was measured in a plugging assay. Whereas all the control females were plugged by day 3 when paired with control males, it took significantly longer for male Six6flox/flox/LHRHcre mice to plug control females, and for Six6flox/flox/LHRHcre females to be plugged by control males [Fig. 3(a)]. In this assay, one Six6flox/flox/LHRHcre female was plugged by a control male and one Six6flox/flox/LHRHcre male plugged a control female. The remaining Six6flox/flox/LHRHcre mice did not plug during the duration of the assay, in contrast to the control matings, which all plugged by day 4 of the assay.

Figure 3.

Six6 flox/flox /LHRH cre mice have disrupted fertility and delayed puberty. (a) Ten-day plugging assay of mice at 3 months of age, Six6flox/flox/LHRHcre (Cre+) were mated to each other as well as Six6flox/flox (Cre−) mice and were compared with a Six6flox/flox mating (n = 3); statistical analysis by Mann-Whitney test. (b) Number of litters produced in 90-day fertility assay between Six6flox/flox/LHRHcre mice mated with Six6flox/flox, as compared with a Six6flox/flox mating (n = 3 to 6). (c) Onset of preputial separation in male mice was measured from day 20 until pubertal onset (n = 3). (d) Onset of vaginal opening was measured from day 20 until pubertal onset (n = 3). (b–d) Data were analyzed by Student t test as compared with control. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01.

The ability of Six6flox/flox/LHRHcre mice to reproduce was assessed via a 90-day fertility assay [Fig. 3(b)]. In this assay, all of the control matings produced litters by the end of the 90-day assay, with most producing three litters during this period [Fig. 3(b)]. Male Six6flox/flox/LHRHcre mice when mated with control female mice did not produce any litters in the 3-month period, and female Six6flox/flox/LHRHcre mice when mated to control males produced very few litters [Fig. 3(b)]. Thus, Six6flox/flox/LHRHcre mice are severely impaired in their ability to produce litters.

Decreased levels of GnRH can also result in delayed or absent puberty (a characteristic of IHH). Therefore, we evaluated whether the Six6flox/flox/LHRHcre mice had altered onset of puberty, as assessed by determining preputial separation in the males and vaginal opening in the females. Control male mice underwent preputial separation at 29 ± 0.40 days, and control female mice underwent vaginal opening at 30 ± 0.32 days; the onset of puberty was significantly delayed in both sexes of Six6flox/flox/LHRHcre mice, with male mice undergoing preputial separation at 45 ± 6.4 days and females vaginal opening at 57 ± 6.0 days [Fig. 3(c) and 3(d)]. Data are given as mean ± SD.

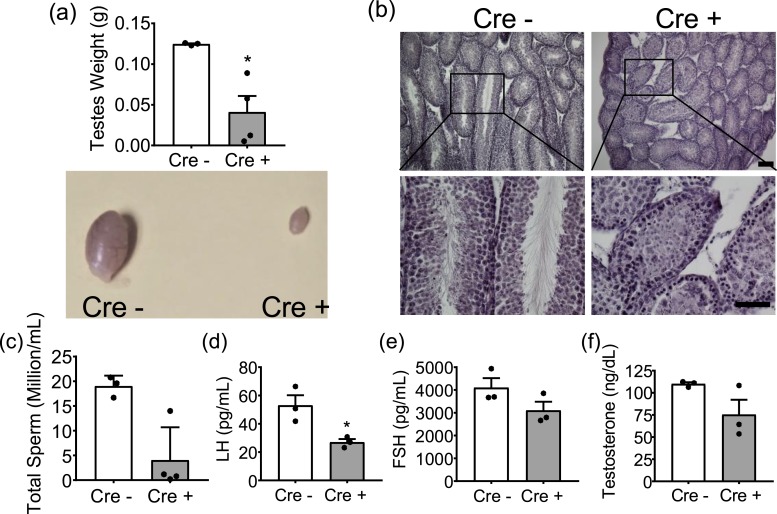

Loss of Six6 within the GnRH neuron results in hypogonadism

We next sought to determine whether the deficiency in GnRH seen in the Six6flox/flox/LHRHcre mice would affect gonadal development. We observed a drastic effect on testicular development with Six6flox/flox/LHRHcre testicles being approximately one fourth the size of control testicles [Fig. 4(a)]. No sperm were present inside three quarters of the Six6flox/flox/LHRHcre testicles [Fig. 4(b)]. Developmental impairment of Six6flox/flox/LHRHcre testes structures explains the infertility seen in the Six6flox/flox/LHRHcre mice. Because several sperm were visible within one of the Six6flox/flox/LHRHcre testes, sperm were counted, with fewer sperm detected within Six6flox/flox/LHRHcre testes [Fig. 4(c)]. Testicular development and spermatogenesis rely on LH and FSH release from the pituitary in response to GnRH (45). Thus, we measured LH and FSH levels, with both LH and FSH being lower between control and Six6flox/flox/LHRHcre mice [Fig. 4(d) and 4(e)], although FSH did not reach statistical significance. Testosterone was also measured, with no significant difference found between control and Six6flox/flox/LHRHcre mice [Fig. 4(f)].

Figure 4.

Six6 flox/flox /LHRH cre male mice are hypogonadal and hypogonadotropic. (a) Testicular weight of Six6flox/flox (Cre−) and Six6flox/flox/LHRHcre (Cre+) mice (n = 3) with image of whole testes below. (b) Images of hematoxylin and eosin–stained Cre− and Cre+ testicles. Scale bar, 100 µm. (c) Sperm count in adult male mice (n = 3 or 4). Serum was collected from adult male mice and assayed for (d) LH (n = 5 or 6), (e) FSH (n = 5 or 6), and (f) testosterone (n = 4 to 7). Scale bar, 1 cm. All data were analyzed by Student t test as compared with control. *P < 0.05.

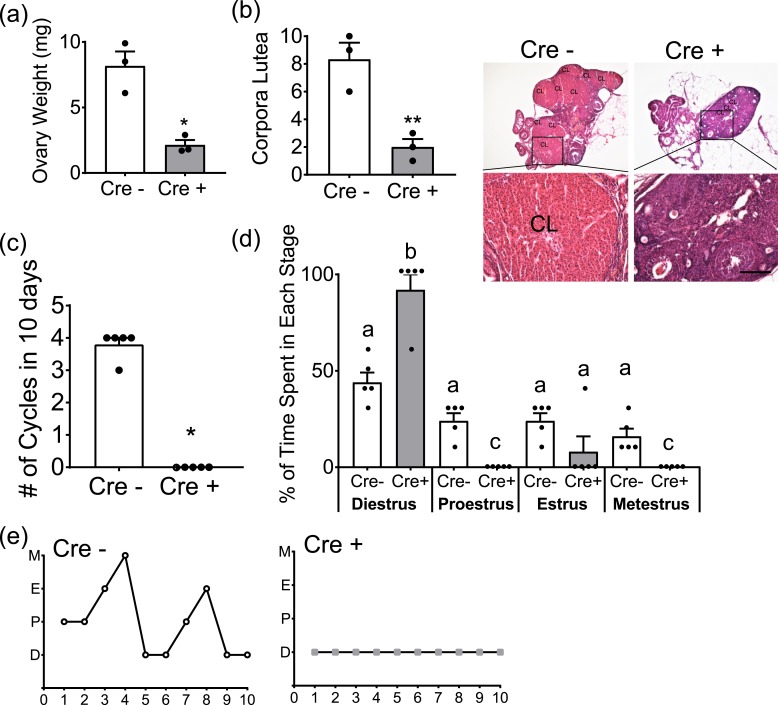

Female gonadal development was similarly affected by the loss of GnRH neurons, but not as drastically as in the males, with the size of Six6flox/flox/LHRHcre ovaries being significantly smaller at ∼30% the size of control ovaries [Fig. 5(a)]. Ovarian histology revealed a significant reduction in the number of corpora lutea in Six6flox/flox/LHRHcre mice [Fig. 5(b)]. The absence of corpora lutea indicates abnormal progression through the estrous cycle and absence of an LH surge. To further assess the ability of Six6flox/flox/LHRHcre females to progress though the estrous cycle given their paucity of GnRH neurons, vaginal smears were collected from 3.5-month-old Six6flox/flox/LHRHcre females and littermates for 10 days. Whereas all control females cycled at least twice during this time frame, only one Six6flox/flox/LHRHcre mouse completed a cycle during this period [Fig. 5(c)]. Six6flox/flox/LHRHcre mice spent the duration of the sampling assay in diestrus, with only one mouse progressing into estrus [Fig. 5(c) and 5(d)].

Figure 5.

Six6 flox/flox /LHRH cre female mice are hypogonadal and have noncyclic estrous cycles. (a) Ovarian weights of Six6flox/flox (Cre−) and Six6flox/flox/LHRHcre (Cre+) females (n = 3). (b) Number of corpora lutea in Cre− and Cre+ mice (n = 3) with images of hematoxylin and eosin–stained ovaries. Scale bar, 100 µm. (c) Estrous cycle was monitored daily in Cre− and Cre+ mice. The number of complete cycles in 10 days was recorded (n = 5). (a–c) Data were analyzed by Student t test as compared with control. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01. (d) The number of days spent in each stage of the estrous cycle was recorded (n = 5). Scale bar, 1 cm. Different letters indicate statistical difference by two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey post hoc test. (e) Representative cycles from one Cre− and one Cre+ mouse. Abbreviations: CL, corpora lutea; D, diestrus; E, estrus; M, metestrus; P, proestrus.

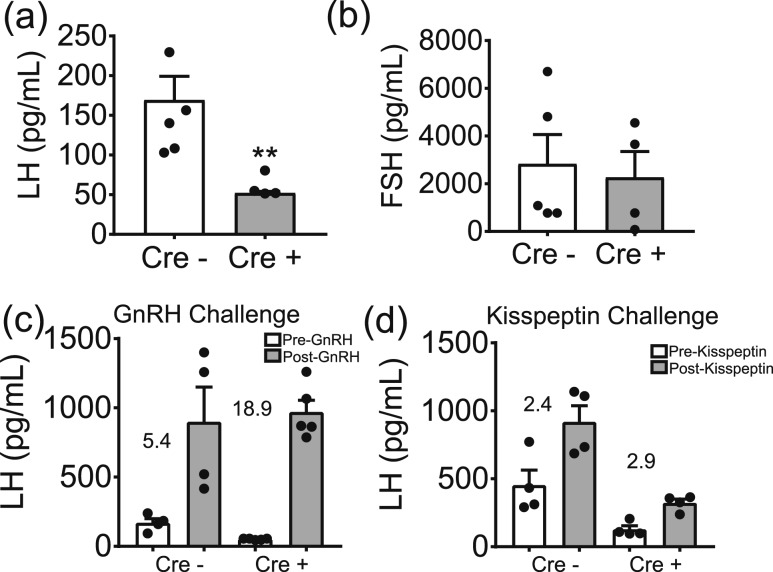

To better understand the hormonal milieu producing this noncyclic phenotype in the Six6flox/flox/LHRHcre mice, we assessed the levels of gonadotropins. Indeed, circulating diestrus LH levels were reduced in Six6flox/flox/LHRHcre females compared with control females; however, no difference was seen in FSH [Fig. 6(a) and 6(b)]. This reduction in LH reflects the deficiency in GnRH neurons in the Six6flox/flox/LHRHcre mice. Finally, to confirm that the decrease in circulating LH is due to a lack of GnRH, and not an effect on LH release at the pituitary, we performed GnRH and kisspeptin challenges. As expected, an increase from basal LH was induced in response to an injection of GnRH in both genotypes [Fig. 6(c)]. A kisspeptin challenge was then conducted to determine whether the remaining population of GnRH neurons in the Six6flox/flox/LHRHcre mice is sufficient to mount an LH response when stimulated by kisspeptin. We did see an increase in the release of LH in the control mice in response to kisspeptin; however, there was no difference in the LH levels detected before and after kisspeptin injection in the Six6flox/flox/LHRHcre mice [Fig. 6(d)], although the fold change in LH release was similar [Fig. 6(d)].

Figure 6.

Six6 flox/flox /LHRH cre females are hypogonadotropic because of deficient GnRH. (a) Serum was collected from adult Six6flox/flox (Cre−) and Six6flox/flox/LHRHcre (Cre+) female diestrus mice and assayed for (a) LH (n = 5 or 6) and (b) FSH (n = 5 or 6). (a and b) Statistical analysis by Student t test as compared with Cre−. **P < 0.01. (c) Serum LH was measured immediately before and 10 min after a single GnRH challenge in Cre− and Cre+ diestrus females (n = 5 or 6). Numerical values on the graphs indicate the average fold-change of Cre− and Cre+ mice LH in response to GnRH injections. Statistical analysis was by two-way repeated-measures ANOVA [there was a statistically significant effect of kisspeptin injection on LH: F(1, 7) = 51.82, P = 0.0002]. (d) Serum LH was measured before and 15 minutes after a single kisspeptin challenge in Cre− and Cre+ diestrus females (n = 5 or 6). Numerical values on the graphs indicate the average fold-change of Cre− and Cre+ mice LH in response to kisspeptin injections. Statistical analysis was by two-way repeated-measures ANOVA. [There was a statistically significant effect of kisspeptin injection on LH, F(1, 6) = 11.09, P = 0.016; there was a statistically significant effect of genotype on LH, F(1, 6) = 48.62, P = 0.0004.]

Loss of Six6 within GnRH neurons results in the loss of Gnrh1 gene expression

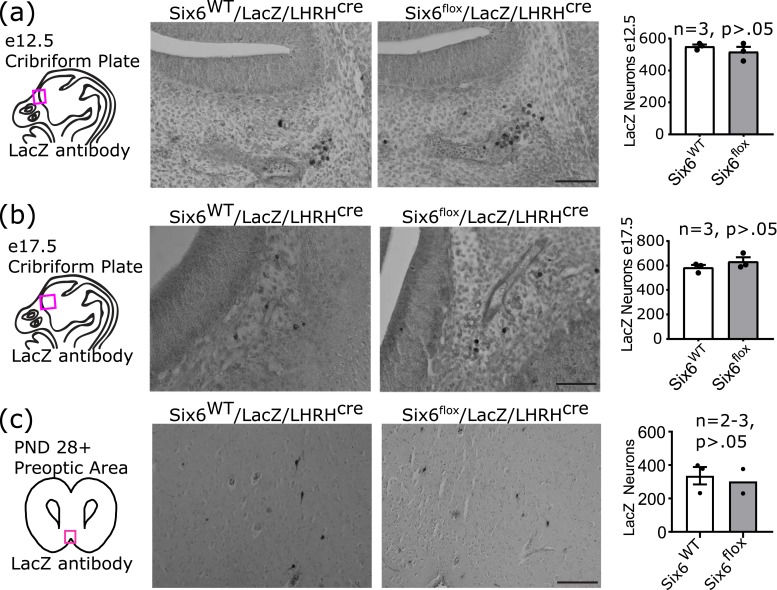

In the Six6flox/flox/LHRHcre mice, ∼90% of GnRH neurons are undetectable by GnRH IHC. When GnRH neurons were counted, the entire heads of the embryos were collected and analyzed for off-path GnRH neurons. None were discovered, indicating that mis-migration does not appear to be the source of the missing GnRH neurons. To discern the mechanism for the absence of GnRH neurons seen in the Six6flox/flox/LHRHcre, lineage tracing was conducted by using Six6flox/flox/RosaLacZ/LHRHcre mice. In these mice, the GnRH neurons are labeled with LacZ for the duration of the life of the neuron, regardless of continued GnRH gene expression. The number of GnRH neurons was counted at e12.5, e17.5, and postnatal days 28 to 112, with equivalent number of LacZ-positive neurons being seen between genotypes at all ages in the Six6flox/flox/RosaLacZ/LHRHcre and RosaLacZ/LHRHcre mice (Fig. 7). In the mature animals, LacZ+ neurons in the Six6flox/flox/RosaLacZ/LHRHcre had a bipolar morphology consistent with mature GnRH neurons. These findings are in contrast to GnRH staining, which is lost by e17.5 [Fig. 2(c)]. Therefore, GnRH neurons are present in the Six6flox/flox/LHRHcre mouse into adulthood but are no longer expressing GnRH.

Figure 7.

Lineage tracing in Six6flox/flox/RosaLacZ/LHRHcre mice identifies a lack of GnRH expression in GnRH neurons. Lineage tracing labels GnRH neurons with LacZ such that they can be identified regardless of continued GnRH expression. Comparison between Six6WT/RosaLacZ/LHRHcre and Six6flox/flox/RosaLacZ/LHRHcre mice. Tracing conducted using LacZ to mark GnRH neurons regardless of continued GnRH expression shows LacZ-positive GnRH neurons at (a) e12.5, (b) e17.5, and (c) postnatal days 28 to 112. Scale bar, 100 µm.

Discussion

Given the complex nature of reproduction, with multiple organs, hormones, and developmental processes necessary for fertility, defects can arise at multiple levels (8, 46–49). GnRH neurons are a key regulator of the HPG axis essential in regulating fertility, pregnancy, puberty, and numerous other physiological life functions (49, 50). Thus, when this neuronal population is compromised, the entire HPG axis is disrupted and infertility ensues (50, 51). GnRH neurons must properly originate, develop, mature, and migrate from the nose into the olfactory bulb and down into the hypothalamus (3). Infertility originating at the level of the GnRH neuron can be due to lack of gene expression, loss of response to crucial input, errors in development, or disruption in migration (52, 53). Either death of GnRH neurons or the loss of GnRH gene expression will result in insufficient gonadotropin production from the pituitary (54). Furthermore, mis-migration of GnRH neurons results in GnRH being released outside of the hypophyseal portal system and not received by the pituitary to stimulate LH and FSH secretion (51, 53). Homeodomain transcription factors are modulators of GnRH neuron migration and development. Several factors, such as Six6, Six3, Vax1, and Otx2, have been associated with GnRH neuron maturation, GnRH gene expression, and infertility (10–13, 28, 42). In this study, we determine the essential role of Six6 within GnRH neurons, and, therefore, in the maintenance of fertility.

Of note, we used two different GnRH promoter–driven Cre-expressing mouse lines for our studies, the GnRHcre and the LHRHcre. Our initial work for lineage tracing in the Six6KO mouse used the Gnrhcre to drive TdTomato expression, whereas the conditional deletion of Six6flox/flox used the LHRHcre. This change in “Cre” use is based on studies that we initiated after completing the lineage tracing in the Six6KO mice, which found LHRHcre to more reliably recapitulate GnRH neuron numbers from early in development into adulthood, than the GnRHcre (42). This recently published study found that GnRH neuron development was similar in mice with Otx2flox/flox deleted with the LHRHcre (42) and the GnRHcre (10). Thus, when GnRH neuron numbers are exclusively evaluated, similar results are obtained when GnRHcre and LHRHcre are used. In agreement with this, Six6flox/flox/GnRHcre mice have comparable GnRH neuron numbers to Six6flox/flox/LHRHcre; however, the ectopic expression of GnRHcre to broad areas of the hypothalamus and septum (42) cause strong impairment of specific behaviors in Six6flox/flox/GnRHcre (55).

Using Six6KO and Six6flox/flox/LHRHcre mice, we reveal that Six6 is essential whether deleted in the whole mouse or only within the GnRH neuron in determining the fate of GnRH neurons. In comparing these two mouse models, we see notable differences in the fate of GnRH neurons. Interestingly, in the whole-body Six6KO model, the entire population of GnRH neurons can be seen in early embryogenesis at e13.5, but ∼90% of this neuronal population is lost through apoptosis by e15.5. Thus, in the whole-body Six6KO mouse, the expression of Six6 in early embryogenesis (e13.5) is not necessary for the generation of GnRH neurons but is essential in maintaining the survival of this population into adulthood. In contrast, in the Six6flox/flox/LHRHcre mouse, detectable GnRH neurons are lost as early as e13.5, with ∼70% of GnRH neurons lacking expression of GnRH at this early stage of embryogenesis. However, these GnRH neurons remain alive and migrate correctly to the hypothalamus, although they no longer express GnRH. Thus, Six6 is not needed within the GnRH neuron to generate this neuronal population or for its migration or survival, but it is needed to maintain GnRH gene expression. Because GnRH neurons die at such an early stage in the Six6KO mouse, it is unknown whether GnRH expression would also be inhibited in the GnRH neurons of the whole-body Six6KO after e13.5, if they survived. However, given that GnRH neurons are present and expressing GnRH at e13.5 in the Six6KO mouse, it is clear that GnRH expression is not decreased at e13.5 as it is in the Six6flox/flox/LHRHcre mouse.

The more severe phenotype in the GnRH-neuron specific KO, as compared with the full-body KO, is unusual and intriguing. We speculate that the less severe phenotypes of the Six6KO may be because loss of Six6 in cells other than the GnRH neuron incites other genes to compensate, such as the closely related Six3 (56). This possible compensation by factors regulating GnRH neuron survival could allow less drastic fertility phenotypes in the Six6KO mouse. Therefore, it is possible that GnRH expression is not lost as early in the global KO model because some other factor compensates for the reduction in Six6. More likely, Six6 may have additional actions within the environment of the neuron that modulate GnRH expression and GnRH neurons survival. These findings show that Six6 has separate and distinct roles within the GnRH neuron itself (the maintenance of GnRH gene expression) and within the environment of the GnRH neuron, where it is required for the survival of GnRH neurons.

Because Six6 is necessary in the migratory environment of the GnRH neuron for the survival of GnRH neurons, Six6 must play a role in maintaining the neuronal population between e13.5 and e15.5. Six6 is known to be expressed along the entire migratory route of the GnRH neuron during development, from the olfactory placode to the olfactory bulb, and also in the hypothalamus at e11.5 and e15.5 (16). It is likely that in the WT mouse, Six6 is exerting its effects on the survival of GnRH neurons at an early stage along this route, perhaps by regulating guidance and survival cues in cells along the pathway to and through the cribriform plate (14, 16). In contrast, the loss of expression of GnRH when Six6 is removed from within the GnRH neuron in the Six6flox/flox/LHRHcre mouse can be explained due to Six6 binding to conserved ATTA sites within the rat GnRH enhancer and promoter to directly regulate the GnRH gene (11). Thus, overexpression of Six6 in GnRH neuronal cell lines causes increased expression of the GnRH promoter (11, 36) providing a mechanism for how the removal of Six6 decreases the expression of GnRH in vivo. The GnRH neuron system is resilient in that many neurons can be lost before a phenotype is observed, indicating the great plasticity of GnRH neurons within the hypothalamus (13, 57). Male mice have been found to be fertile with as few as 12% of their GnRH neurons remaining (57). The requirement for females is decidedly higher with aspects of fertility being compromised when the number of GnRH neurons is reduced to 34% of the normal population (57). The Six6flox/flox/LHRHcre mice have ∼50 GnRH neurons and thus are left with <10% of the normal population of GnRH neurons. Thus, the fertility impairment in the Six6flox/flox/LHRHcre females is expected; however, in the case of the males, their deficit hovers around the precipice of the number of GnRH neurons required for fertility. In this case, the severe male infertility is somewhat surprising, although one male mouse was successfully plugged and impregnated a control female mouse.

To confirm that the reproductive deficiency of Six6flox/flox/LHRHcre mice arises at the level of GnRH neurons, we challenged females with injections of GnRH. The fact that Six6flox/flox/LHRHcre mice could elicit a response to an injection of GnRH indicates a functioning and responsive pituitary. Additionally, this confirms that low gonadotropin levels in the Six6flox/flox/LHRHcre mice were not due to a lack of responsiveness of the pituitary to GnRH, but to insufficient GnRH input to the pituitary. Thus, we identified the source of infertility in the Six6flox/flox/LHRHcre mouse model to be the lack of GnRH expression at the level of the hypothalamus. Although the fold change of LH in response to kisspeptin in the Six6flox/flox/LHRHcre mice was similar to that of the control mice, there was no statistical difference between the LH levels before and after the kisspeptin injection in the Six6flox/flox/LHRHcre mice. Of note, we are using supra-physiological levels of kisspeptin and thus probably stimulated GnRH release from all the remaining terminals, allowing LH to be released despite the paltry number of GnRH neurons remaining in the Six6flox/flox/LHRHcre mice.

Six6 has been implicated as an essential regulator of development in several neuronal populations. Further studies of Six6 in development suggest its involvement in reduced proliferation and increased apoptosis (18). Studies of the role of Six6 in the eye have shown that the global loss of SIX6 results in early exit from the cell cycle of retinal progenitor cells, leading to an absence of retinal ganglion cells, the terminally differentiated cell of this lineage (18). It is believed that SIX family proteins may serve as a nexus point for the balance between proliferation and cell death in the development of tissues (58). Indeed, studies of Six3, a very closely related homeodomain transcription factor to Six6, demonstrate a role for Six3 in the proliferation of olfactory tissues (59). The absence of Six3 has also been associated with apoptosis in mice in the anterior neural plate and in neuroretinal cells (60, 61). Additional evidence of the essential role of SIX3 in the survival of cells has been shown in medaka fish and in Drosophila species, wherein mutations in the Six3 homolog resulted in massive cell death (62). Thus, our work bolsters the growing evidence that Six6 is a key regulator in neuronal cell survival.

This insight into the essential developmental role of Six6 adds to the growing knowledge of the roles homeodomain transcription factors play in the development and fate of GnRH neurons. Otx2, for example, has been identified as an essential transcription factor in the maintenance of GnRH neurons, as removal of Otx2 from within the GnRH neuron resulted in apoptosis of GnRH neurons (10). In contrast, Six3 has been identified as mediating the proper migration of GnRH neurons (59), but its loss within GnRH neurons increases the number of GnRH neurons in adulthood (59) consistent with its role as a repressor of GnRH gene expression (11). Furthermore, another homeodomain transcription factor, Vax1, has been identified as essential within this neuronal population for maintaining GnRH expression (36). In addition to adding to our current knowledge of the transcription network that controls GnRH neurons, our work provides insight into the development of GnRH neurons themselves. GnRH neurons originate in the nasal placode and migrate along a carefully orchestrated pathway out of the placode to cross the cribriform plate (49, 54, 63–65). They then turn caudally to move down into the hypothalamus during prenatal development (49, 54, 63–65). This route is delineated in part by the axonal projections to which GnRH neurons attach and migrate along, and in part by guidance and chemosensory cues (66–68). Disruptions in their guidance or movement result in IHH (47). When such a disruption is located in the nasal epithelium, the development of olfactory structures is also disrupted, resulting in the IHH subtype Kallmann syndrome (47). Recent work has focused on the role of homeodomain factors (e.g., Vax1, Otx2, Dlx1/2, and Six3) in this journey and has used mouse models to illuminate the intricate mechanisms at play in the successful migration and development of GnRH neurons (12, 28, 36, 59, 69, 70). Our work demonstrates the essential role of Six6 in this process and illuminates the involvement of the Six6 homeodomain transcription factor in the survival of GnRH neurons and in the proper migration and expression of GnRH.

IHH is engendered by GnRH deficiency, which can result from alterations in the migration, development, and/or survival of GnRH neurons (5, 47, 51). Such disruptions in the levels of GnRH can also impair a multitude of physiological functions, including fetal development, pregnancy, puberty, and menopause (5, 50, 51). It is likely that through identification and understanding of the rare genetic variants that underlie GnRH deficiency, we may be able to illuminate mechanisms behind precocious or delayed puberty. Despite the important ramifications of GnRH deficiency, there is much still to learn about the regulation of the GnRH neuron. The work presented here provides insight into the development and maturation of GnRH neurons and the dependence of these neurons on the transcription factor Six6.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Jason D. Meadows, Mary Jean Sunshine, and Ichiko Saotome for technical assistance on this project. We also thank Ella Kothari and Jun Zhao of the University of California, San Diego, Transgenic Mouse and Embryonic Stem Cell Core Facility for assistance in creating the Six6 flox mouse and EUCOMM for the Six6 knockout first construct.

Financial Support: This work was supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants R01 HD082567 and R01 HD072754 (P.L.M.) and by P50 HD012303 as part of the National Centers for Translational Research in Reproduction and Infertility (P.L.M.). P.L.M. was partially supported by P30 DK063491, P42 ES010337, and P30 CA023100. E.C.P. was partially supported by NIH R25 GM083275 and F31 HD098652. H.M.H. was partially supported by K99/R00 HD084759. K.J.T. was also partially supported by F32 HD090837 and T32 HD007203. The University of California, San Diego, Transgenic Mouse and Embryonic Stem Cell Core Facility is supported by P30 DK063491, P42 ES010337, and P30 CA023100. The University of Virginia Ligand Assay Core was supported by NIH P50 HD028934.

Glossary

Abbreviations:

- e

embryonic day

- EUCOMM

European Conditional Mouse Mutagenesis Program

- FRT

flippase recombinase target

- HPG

hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal

- IHC

immunohistochemistry

- IHH

idiopathic hypogonadotropic hypogonadism

- inter-ACOV

inter-assay coefficient of variation

- intra-ACOV

intra-assay coefficient of variation

- KO

knockout

- RFP

red fluorescent protein

- Six6

sine oculis–related homeobox 6

- WT

wild-type

Additional Information

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to disclose.

Data Availability:

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article or in the data repositories listed in References.

References and Notes

- 1. Mason AJ, Pitts SL, Nikolics K, Szonyi E, Wilcox JN, Seeburg PH, Stewart TA. The hypogonadal mouse: reproductive functions restored by gene therapy. Science. 1986;234(4782):1372–1378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Valdes-Socin H, Rubio Almanza M, Tome Fernandez-Ladreda M, Debray FG, Bours V, Beckers A. Reproduction, smell, and neurodevelopmental disorders: genetic defects in different hypogonadotropic hypogonadal syndromes. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2014;5(Jul 9):109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Wray S. From nose to brain: development of gonadotrophin-releasing hormone-1 neurones. J Neuroendocrinol. 2010;22(7):743–753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Whitlock KE. Origin and development of GnRH neurons. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2005;16(4):145–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bianco SD, Kaiser UB. The genetic and molecular basis of idiopathic hypogonadotropic hypogonadism. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2009;5(10):569–576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hardelin JP. Kallmann syndrome: towards molecular pathogenesis. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2001;179(1-2):75–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Pitteloud N, Quinton R, Pearce S, Raivio T, Acierno J, Dwyer A, Plummer L, Hughes V, Seminara S, Cheng YZ, Li WP, Maccoll G, Eliseenkova AV, Olsen SK, Ibrahimi OA, Hayes FJ, Boepple P, Hall JE, Bouloux P, Mohammadi M, Crowley W. Digenic mutations account for variable phenotypes in idiopathic hypogonadotropic hypogonadism. J Clin Invest. 2007;117(2):457–463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. González-Martínez D, Hu Y, Bouloux PM. Ontogeny of GnRH and olfactory neuronal systems in man: novel insights from the investigation of inherited forms of Kallmann’s syndrome. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2004;25(2):108–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Givens ML, Rave-Harel N, Goonewardena VD, Kurotani R, Berdy SE, Swan CH, Rubenstein JL, Robert B, Mellon PL. Developmental regulation of gonadotropin-releasing hormone gene expression by the MSX and DLX homeodomain protein families. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(19):19156–19165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Diaczok D, DiVall S, Matsuo I, Wondisford FE, Wolfe AM, Radovick S. Deletion of Otx2 in GnRH neurons results in a mouse model of hypogonadotropic hypogonadism. Mol Endocrinol. 2011;25(5):833–846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Larder R, Clark DD, Miller NL, Mellon PL. Hypothalamic dysregulation and infertility in mice lacking the homeodomain protein Six6. J Neurosci. 2011;31(2):426–438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Larder R, Kimura I, Meadows J, Clark DD, Mayo S, Mellon PL. Gene dosage of Otx2 is important for fertility in male mice. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2013;377(1-2):16–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hoffmann H, Pandolfi E, Larder R, Mellon P. Haploinsufficiency of Homeodomain Proteins Six3, Vax1, and Otx2, Causes Subfertility in Mice Via Distinct Mechanisms. Neuroendocrinology. 2018. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Jean D, Bernier G, Gruss P. Six6 (Optx2) is a novel murine Six3-related homeobox gene that demarcates the presumptive pituitary/hypothalamic axis and the ventral optic stalk. Mech Dev. 1999;84(1-2):31–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kobayashi M, Taniura H, Yoshikawa K. Ectopic expression of necdin induces differentiation of mouse neuroblastoma cells. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(44):42128–42135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Conte I, Morcillo J, Bovolenta P. Comparative analysis of Six 3 and Six 6 distribution in the developing and adult mouse brain. Dev Dyn. 2005;234(3):718–725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. RRID:MGI:3613489, www.informatics.jax.org/allele/MGI:3613016.

- 18. Li X, Perissi V, Liu F, Rose DW, Rosenfeld MG. Tissue-specific regulation of retinal and pituitary precursor cell proliferation. Science. 2002;297(5584):1180–1183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Rodríguez CI, Buchholz F, Galloway J, Sequerra R, Kasper J, Ayala R, Stewart AF, Dymecki SM. High-efficiency deleter mice show that FLPe is an alternative to Cre-loxP. Nat Genet. 2000;25(2):139–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. RRID:IMSR_JAX:005703, www.jax.org/strain/003800.

- 21. RRID:MGI:5004854, www.jax.org/strain/021207.

- 22. Yoon H, Enquist LW, Dulac C. Olfactory inputs to hypothalamic neurons controlling reproduction and fertility. Cell. 2005;123(4):669–682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. RRID:MGI:104735, www.jax.org/strain/007909.

- 24. Srinivas S, Watanabe T, Lin CS, William CM, Tanabe Y, Jessell TM, Costantini F. Cre reporter strains produced by targeted insertion of EYFP and ECFP into the ROSA26 locus. BMC Dev Biol 2001;1(March 27):4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25. RRID:IMSR_JAX:003309, www.jax.org/strain/003309.

- 26. RRID:MGI:4442244, www.informatics.jax.org/allele/genoview/MGI:4442244.

- 27. Wolfe A, Divall S, Singh SP, Nikrodhanond AA, Baria AT, Le WW, Hoffman GE, Radovick S. Temporal and spatial regulation of CRE recombinase expression in gonadotrophin-releasing hormone neurones in the mouse. J Neuroendocrinol. 2008;20(7):909–916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hoffmann HM, Tamrazian A, Xie H, Pérez-Millán MI, Kauffman AS, Mellon PL. Heterozygous deletion of ventral anterior homeobox (vax1) causes subfertility in mice. Endocrinology. 2014;155(10):4043–4053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hoffmann HM. Determination of reproductive competence by confirming pubertal onset and performing a fertility assay in mice and rats. J Vis Exp. 20181(40):e58352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. RRID:AB_325077, https://scicrunch.org/resolver/AB_325077.

- 31. RRID:AB_572248, https://scicrunch.org/resolver/AB_572248.

- 32. Paxinos G, Franklin KBJ. The mouse brain in stereotxic coordinates. Amsterdam: Academic Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 33. RRID:AB_945213, https://scicrunch.org/resolver/AB_945213.

- 34. RRID:AB_307210, https://scicrunch.org/resolver/AB_307210.

- 35. Messina A, Langlet F, Chachlaki K, Roa J, Rasika S, Jouy N, Gallet S, Gaytan F, Parkash J, Tena-Sempere M, Giacobini P, Prevot V. A microRNA switch regulates the rise in hypothalamic GnRH production before puberty [published correction appears in Nat Neurosci. 2016;19(8):1115]. Nat Neurosci. 2016;19(6):835–844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Hoffmann HM, Trang C, Gong P, Kimura I, Pandolfi EC, Mellon PL. Deletion of Vax1 from GnRH neurons abolishes GnRH expression and leads to hypogonadism and infertility. J Neurosci. 2016;36(12):3506–3518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Cariboni A, Hickok J, Rakic S, Andrews W, Maggi R, Tischkau S, Parnavelas JG. Neuropilins and their ligands are important in the migration of gonadotropin-releasing hormone neurons. J Neurosci. 2007;27(9):2387–2395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Tsai PS, Moenter SM, Postigo HR, El Majdoubi M, Pak TR, Gill JC, Paruthiyil S, Werner S, Weiner RI. Targeted expression of a dominant-negative fibroblast growth factor (FGF) receptor in gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) neurons reduces FGF responsiveness and the size of GnRH neuronal population. Mol Endocrinol. 2005;19(1):225–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Gill JC, Wadas B, Chen P, Portillo W, Reyna A, Jorgensen E, Mani S, Schwarting GA, Moenter SM, Tobet S, Kaiser UB. The gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) neuronal population is normal in size and distribution in GnRH-deficient and GnRH receptor-mutant hypogonadal mice. Endocrinology. 2008;149(9):4596–4604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Gill JC, Moenter SM, Tsai PS. Developmental regulation of gonadotropin-releasing hormone neurons by fibroblast growth factor signaling. Endocrinology. 2004;145(8):3830–3839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Chung WC, Moyle SS, Tsai PS. Fibroblast growth factor 8 signaling through fibroblast growth factor receptor 1 is required for the emergence of gonadotropin-releasing hormone neurons. Endocrinology. 2008;149(10):4997–5003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Hoffmann HM, Larder R, Lee JS, Hu RJ, Trang C, Devries BM, Clark DD, Mellon PL. Differential CRE expression in Lhrh-Cre and Gnrh-Cre alleles and the impact on fertility in Otx2-flox mice. Neuroendocrinology. 2019;108(4):328–342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Novaira HJ, Fadoju D, Diaczok D, Radovick S. Genetic mechanisms mediating kisspeptin regulation of GnRH gene expression. J Neurosci. 2012;32(48):17391–17400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. DiVall SA, Herrera D, Sklar B, Wu S, Wondisford F, Radovick S, Wolfe A. Insulin receptor signaling in the GnRH neuron plays a role in the abnormal GnRH pulsatility of obese female mice. PLoS One. 2015;10(3):e0119995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Schinckel AP, Johnson RK, Kittok RJ. Relationships among measures of testicular development and endocrine function in boars. J Anim Sci. 1984;58(5):1255–1261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Beaver LM, Gvakharia BO, Vollintine TS, Hege DM, Stanewsky R, Giebultowicz JM. Loss of circadian clock function decreases reproductive fitness in males of Drosophila melanogaster. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99(4):2134–2139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Cadman SM, Kim SH, Hu Y, González-Martínez D, Bouloux PM. Molecular pathogenesis of Kallmann’s syndrome. Horm Res. 2007;67(5):231–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. MacColl G, Bouloux P, Quinton R. Kallmann syndrome: adhesion, afferents, and anosmia. Neuron. 2002;34(5):675–678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Wierman ME, Kiseljak-Vassiliades K, Tobet S. Gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) neuron migration: initiation, maintenance and cessation as critical steps to ensure normal reproductive function. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2011;32(1):43–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Balasubramanian R, Dwyer A, Seminara SB, Pitteloud N, Kaiser UB, Crowley WF Jr. Human GnRH deficiency: a unique disease model to unravel the ontogeny of GnRH neurons. Neuroendocrinology. 2010;92(2):81–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Seminara SB, Hayes FJ, Crowley WF Jr. Gonadotropin-releasing hormone deficiency in the human (idiopathic hypogonadotropic hypogonadism and Kallmann’s syndrome): pathophysiological and genetic considerations. Endocr Rev. 1998;19(5):521–539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Pitteloud N, Meysing A, Quinton R, Acierno JS Jr., Dwyer AA, Plummer L, Fliers E, Boepple P, Hayes F, Seminara S, Hughes VA, Ma J, Bouloux P, Mohammadi M, Crowley WF Jr. Mutations in fibroblast growth factor receptor 1 cause Kallmann syndrome with a wide spectrum of reproductive phenotypes. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2006;254–255(July 25):60–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Schwarting GA, Wierman ME, Tobet SA. Gonadotropin-releasing hormone neuronal migration. Semin Reprod Med. 2007;25(5):305–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Wierman ME, Bruder JM, Kepa JK. Regulation of gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) gene expression in hypothalamic neuronal cells. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 1995;15(1):79–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Unpublished data.

- 56. Xie H, Hoffmann HM, Meadows JD, Mayo SL, Trang C, Leming SS, Maruggi C, Davis SW, Larder R, Mellon PL. Homeodomain proteins SIX3 and SIX6 regulate gonadotrope-specific genes during pituitary development. Mol Endocrinol. 2015;29(6):842–855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Herbison AE, Porteous R, Pape JR, Mora JM, Hurst PR. Gonadotropin-releasing hormone neuron requirements for puberty, ovulation, and fertility. Endocrinology. 2008;149(2):597–604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Kumar JP. The sine oculis homeobox (SIX) family of transcription factors as regulators of development and disease. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2009;66(4):565–583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Pandolfi EC, Hoffmann HM, Schoeller EL, Gorman MR, Mellon PL. Haploinsufficiency of SIX3 abolishes male reproductive behavior through disrupted olfactory development, and impairs female fertility through disrupted GnRH neuron migration. Mol Neurobiol. 2018;55(11):8709–8727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Kawakami K, Sato S, Ozaki H, Ikeda K. Six family genes--structure and function as transcription factors and their roles in development. BioEssays. 2000;22(7):616–626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Carl M, Loosli F, Wittbrodt J. Six3 inactivation reveals its essential role for the formation and patterning of the vertebrate eye. Development. 2002;129(17):4057–4063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Cheyette BN, Green PJ, Martin K, Garren H, Hartenstein V, Zipursky SL. The Drosophila sine oculis locus encodes a homeodomain-containing protein required for the development of the entire visual system. Neuron. 1994;12(5):977–996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Schwanzel-Fukuda M. Origin and migration of luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone neurons in mammals. Microsc Res Tech. 1999;44(1):2–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Wierman ME, Pawlowski JE, Allen MP, Xu M, Linseman DA, Nielsen-Preiss S. Molecular mechanisms of gonadotropin-releasing hormone neuronal migration. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2004;15(3):96–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Wolfe A, Kim HH, Radovick S. The GnRH neuron: molecular aspects of migration, gene expression and regulation. Prog Brain Res. 2002;141(1):243–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Tobet SA, Hanna IK, Schwarting GA. Migration of neurons containing gonadotropin releasing hormone (GnRH) in slices from embryonic nasal compartment and forebrain. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 1996;97(2):287–292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Tobet SA, Schwarting GA. Minireview: recent progress in gonadotropin-releasing hormone neuronal migration. Endocrinology. 2006;147(3):1159–1165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Simonian SX, Herbison AE. Regulation of gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) gene expression during GnRH neuron migration in the mouse. Neuroendocrinology. 2001;73(3):149–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Kelley CG, Lavorgna G, Clark ME, Boncinelli E, Mellon PL. The Otx2 homeoprotein regulates expression from the gonadotropin-releasing hormone proximal promoter. Mol Endocrinol. 2000;14(8):1246–1256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Larder R, Mellon PL. Otx2 induction of the gonadotropin-releasing hormone promoter is modulated by direct interactions with Grg co-repressors. J Biol Chem. 2009;284(25):16966–16978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article or in the data repositories listed in References.