Using trio exome sequencing, Horn et al. identify de novo gain-of-function mutations in PAK1 in four unrelated individuals with intellectual disability, macrocephaly and seizures. PAK1 encodes a p21-activated kinase, which has been implicated in brain development and control of brain size.

Keywords: de novo, exome sequencing, intellectual disability, macrocephaly, seizures

Abstract

Using trio exome sequencing, we identified de novo heterozygous missense variants in PAK1 in four unrelated individuals with intellectual disability, macrocephaly and seizures. PAK1 encodes the p21-activated kinase, a major driver of neuronal development in humans and other organisms. In normal neurons, PAK1 dimers reside in a trans-inhibited conformation, where each autoinhibitory domain covers the kinase domain of the other monomer. Upon GTPase binding via CDC42 or RAC1, the PAK1 dimers dissociate and become activated. All identified variants are located within or close to the autoinhibitory switch domain that is necessary for trans-inhibition of resting PAK1 dimers. Protein modelling supports a model of reduced ability of regular autoinhibition, suggesting a gain of function mechanism for the identified missense variants. Alleviated dissociation into monomers, autophosphorylation and activation of PAK1 influences the actin dynamics of neurite outgrowth. Based on our clinical and genetic data, as well as the role of PAK1 in brain development, we suggest that gain of function pathogenic de novo missense variants in PAK1 lead to moderate-to-severe intellectual disability, macrocephaly caused by the presence of megalencephaly and ventriculomegaly, (febrile) seizures and autism-like behaviour.

Introduction

With a prevalence of about 1–3%, intellectual disability is a major health and socioeconomic issue (Maulik et al., 2011). Intellectual disability is genetically highly heterogeneous, with each recognized cause affecting only a small fraction of all patients (Vissers et al., 2016). Services for people with intellectual disability increasingly focus on innovative and personalized therapies. Major research efforts have used efficient molecular diagnostic tools for rare diseases, especially exome sequencing given its high diagnostic yield (Ligt et al., 2012; Boycott et al., 2017; Trujillano et al., 2017), thus providing knowledge of specific genetic variants as a prerequisite for personalized therapy in cases where mechanistic insights on the affected genes and proteins exist.

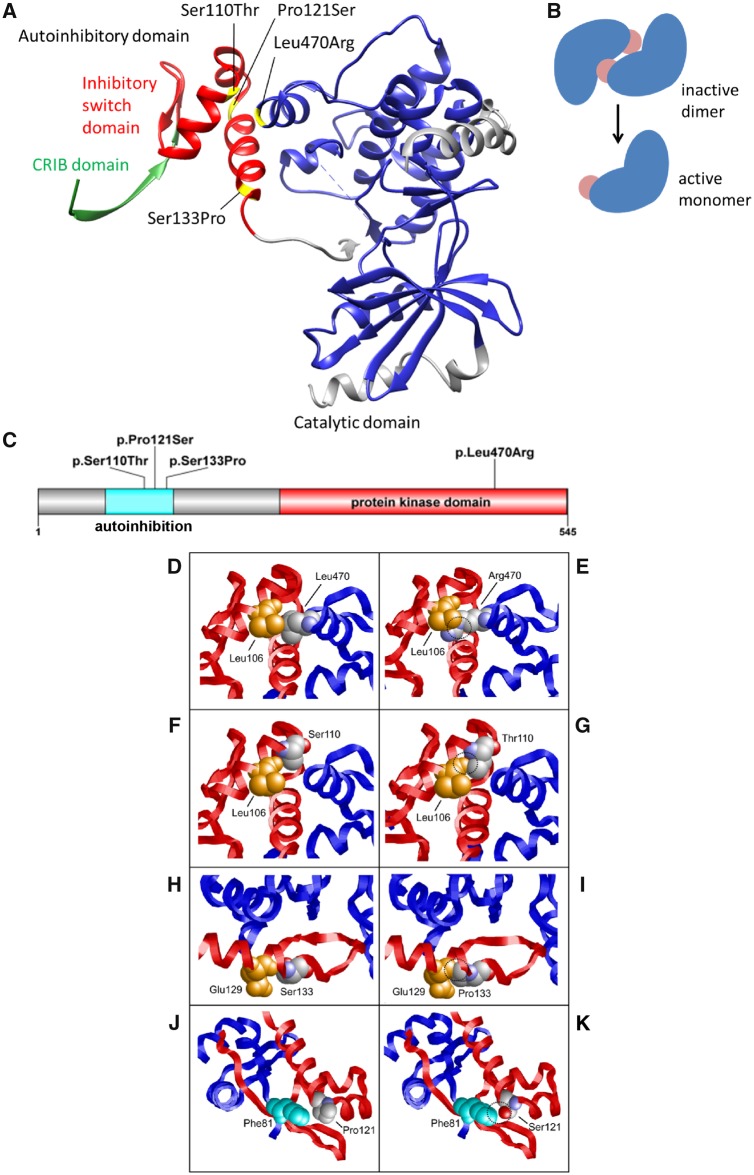

At four centres in Germany, the Netherlands, the USA and Israel, we ascertained four unrelated individuals with a neurodevelopmental disorder, including intellectual disability, seizures and macrocephaly. We performed exome sequencing to identify the underlying genetic cause of the disease. Here we present data that indicate a pathogenic mechanism of PAK1 mutations by a dominant gain-of-function effect. De novo PAK1 missense pathogenic variants have also recently been described in two cases with intellectual disability, macrocephaly, seizures and speech delay (MIM: 618158) (Harms et al., 2018). Human PAK1 is a 545-amino acid (aa) protein with two major domains, an autoregulatory domain and a protein kinase domain (Fig. 1). In its inactive form, it homodimerizes by interacting and binding at a region within the autoregulatory domain (74–132 aa) masking the active site of the kinase. Therefore the autoregulatory domain is important for the autoinhibition of this kinase, and this mechanism has been well described for PAK1 (Lei et al., 2000; Parrini et al., 2002; Pirruccello et al., 2006). In the inhibited state, the inhibitory-switch domain of one homodimer overlaps the GTPase binding region (75–105 aa) of the other homodimer and a polypeptide segment covers the kinase cleft (Parrini et al., 2002). During activation, GTPase binding triggers refolding of the inhibitory-switch domain, disrupting the PAK1 dimer and leading to rearrangement of the kinase active site into a catalytically competent state.

Figure 1.

Structural effects of the PAK1 variants. (A) Protein structure of PAK1 with the catalytic domain (270–521 aa, blue) and the autoinhibitory domain (70–140 aa), comprising the Cdc42 Rac Interactive Binding (CRIB) domain (75–86 aa, green) and the inhibitory switch domain (87–136 aa, red, https://www.uniprot.org). Variants Leu470Arg, Ser133Pro and Ser110Thr affect the contact zone of the catalytic and inhibitory switch domains. Pro121Ser is located in the interface between both PAK1 monomers (see also Supplementary Fig. 1). The CRIB domain (green) mediates activation of PAK1 by binding of RAC1 and CDC42. (B) Autoinhibiton of PAK1. Autoinhibitory domains (light red) of inactive dimers cover the active site in-trans. After CDC42 or RAC1 binding, monomers dissociate, PAK1 autophosphorylation creates the active form of the protein. (C) Distribution of PAK1 variants across the coding region. (D and E) Leu470 forms tight hydrophobic interactions with Leu106, whereas the longer and charged Arg470 sidechain results in clashes with Leu106. In all panels the site of mutation is shown in space-filled presentation and coloured according to the atom types. Key interacting residues are shown in space-fill and are coloured orange or cyan. The two subunits of PAK1 are shown as red and blue ribbon, respectively. Sites of unfavourable interactions in the variants are highlighted by dashed circles. (F and G) Ser110 interacts with Leu106, whereas the additional methyl group present in the Thr110 sidechain forms clashes with Leu106. (H and I) Ser133 forms a backbone hydrogen bond with Glu129 within an α-helix. The presence of a cyclic sidechain in Pro133 results in a loss of this hydrogen bond and additionally causes steric clashes with Glu129. (J and K) Pro121 is located at a kink between two α-helices and near Phe81 of the second subunit. Replacement by a more flexible serine is expected to destabilize the kink and additionally creates an unfavourable interaction by placing the polar sidechain hydroxyl group in close proximity to the hydrophobic Phe81 sidechain.

We propose that PAK1 disease-causing variants result in activation of the PAK1-LIMK1 pathway, a mechanism that is discussed in fragile X syndrome (FXS) (Hayashi et al., 2007; Pyronneau et al., 2017).

Materials and methods

Subjects

Informed consent of all examined individuals and/or their guardians was obtained according to Institutional Review Board approved research protocols, including consent for publishing of the clinical as well as the genetic and genomic results. In Proband 4, genetic testing was carried out as part of routine clinical care and therefore institutional ethics approval was not required. Informed consent has been obtained for the published photo.

Exome sequencing

The study design comprised whole exome-sequencing (WES), genotype calling and the comparison of parent-offspring trios for the identification of rare variants in coding sequence associated with the observed human phenotype. We performed trio or family exome sequencing for all four probands and their biological parents according to standard methods (Supplementary material). Reported variants for all individuals were confirmed with Sanger dideoxynucleotide sequencing.

Protein modelling and analysis of gene expression

Energetic calculations of the observed protein changes were carried out using BindProfX (Xiong et al., 2017) and visualized using UCSC Chimera v.1.12 (Pettersen et al., 2004). To determine an unbiased set of relevant PAK1 interacting genes for comparisons, we analysed gene expression in normal brain development using the R2 Genomics analysis and visualization platform (dataset brspv10rs). Interacting genes were predicted by using GENEMANIA (https://genemania.org).

Limitations of the study

Limitations of the retrospective case series are to be noted as there is limited information on the seizure types of the patients, with respect to detailed descriptions of seizures and post-ictal symptoms to classify them in more detail.

Data availability

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and/or its Supplementary material.

Results

The probands presented with moderate to profound intellectual disability, seizures, macrocephaly, ventriculomegaly and other abnormalities in brain MRI, muscular hypotonia, and abnormal gait (Table 1, see detailed clinical descriptions in the Supplementary material). The analyses revealed de novo missense variants in PAK1 in the four probands, c.1409T>G in exon 13 of 16 leading to p.(Leu470Arg) in Proband 1, and three changes in exon 4: c.397T>C; p.(Ser133Pro) in Proband 2, c.361C>T; p.(Pro121Ser) in Proband 3, and c.328T>A; p.(Ser110Thr) in Proband 4 (Table 1 and Supplementary Table 1). None of the variants in PAK1 have been observed in the gnomAD database (accessed in September 2018) or in internal databases. All of the variants are predicted to be pathogenic by in silico bioinformatics prediction algorithms and reaching between the top 1% and 0.1% CADD scores (Kircher et al., 2014). In addition, all variants affect highly conserved amino acid residues and nucleotides, except for a moderately conserved nucleotide in Proband 4. PAK1 shows fewer missense variants than expected by chance with a z-score of 4.16 (Lek et al., 2016), suggesting that heterozygous missense variants are less tolerated. In addition, in silico modelling of protein structures of wild-type and altered PAK1 revealed that all four identified variants similarly lead to a disturbance of the autoinhibition mechanism (Fig. 1).

Table 1.

Clinical features of individuals with predicted missense variants in PAK1

| Proband 1 | Proband 2 | Proband 3 | Proband 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| cDNA change | c.1409T>G | c.397T>C | c.361C>T | c.328T>A |

| Amino acid change | p.(Leu470Arg) | (p.Ser133Pro) | p.(Pro121Ser) | p.(Ser110Thr) |

| Ethnicity | Caucasian | Caucasian | Morocco | Sephardi Jew |

| Age at last exam/Sex | 4 y/Female | 17 y/Male | 20 y/Male | 8 y/Male |

| HC last examination | 55.5 cm (>P99 +3.80 SD) | 59.8 cm (P98 +2.07 SD) | 61.5 cm (>P99 +2.95 SD) | 59.5 cm (>P99 +4.93 SD) |

| BMI | 13.9 (P14 −1.09 SD) | Not measured | 24.7 (P84 +0.98 SD) | 15.3 (P33 −0.45 SD) |

| Pregnancy | Maternal gestational diabetes, pre-eclampsia | No anomalies | No anomalies | Choroid plexus cyst |

| Birth at gestational week | 30 weeks | 32 weeks | 34 weeks | 40 weeks |

| Birth parameters | Weight 1120 g (P25 −0.69 SD) | Weight 2268 g (P86 +1.07 SD) | Weight 2100 g (P34 −0.4 SD) | Weight 2800 g (P3 −1.87SD) |

| Length 41 cm (P67 +0.45 SD) | Length NA | Length NA | Length NA | |

| HC 27.5 cm (P43 −0.18 SD) | HC NA | HC NA | HC 34.5 cm (P20 −0.85 SD) | |

| APGAR 8/9/10 | APGAR NA | APGAR 6/8/9 | APGAR NA | |

| Neonatal period | Primary C-section | Spontaneous uncomplicated premature vaginal delivery NICU 4 weeks | IRDS, 4 days artificial respiration (CPAP and IPPV) | NA |

| NICU | Neonatal jaundice (phototherapy for 3 days) | |||

| Congenital anomalies | Partial 2–4 toe syndactyly; long fingers | Partial 2–3 toe syndactyly; macrocephaly | No anomalies | No anomalies |

| Postnatal growth (Strauss et al., 2018), HC | At 3 months: HC 37 cm (P89 +1.2 SD) | At 13 months: HC 52 cm (>P99 +3.96 SD), length 76 cm (P26 −0.65SD), weight 10.84 kg (P62 +0.31SD) | At 12 y: HC 59 cm (>P99 +3.27 SD), length 140 cm (P7 −1.49 SD) | At 18 months: HC 58 cm (>P99 +7.76 SD) |

| At 6 months: HC 43.5 cm (P97 +1.9 SD) | ||||

| At 12 months: HC 48.3 cm (>P97 +2.75 SD) | ||||

| Developmental delay | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Intellectual disability | Moderate to severe | Profound | Moderate to severe | Profound |

| Speech and language | Delayed, no active speech | Non-verbal | Delayed, sentences at age of 10 y | Non-verbal |

| Mental health disorders | Autistic traits | Autism | ADHD | Autism |

| Facial dysmorphism/physical signs | Macrocephaly, frontal bossing, thin upper vermillion, broad nasal bridge, low-set posteriorly rotated ears | Craniofacial disproportion | Macrocephaly | Macrocephaly, strabismus |

| Muscular tone | Hypotonia | Initial hypotonia, later spastic quadriplegia | First year hypotonia | Hypotonia |

| Walking abilities | Unstable gait | No walking | Walking, mild ataxia | Ataxic, unstable gait |

| Brain/MRI | MRI: thin corpus callosum, ventriculomegaly, globular and mildly amorphous hippocampi bilaterally | MRI: thin corpus callosum, cerebellar atrophy with widening of the sulci, megalencephaly, ventriculomegaly, mildly small and amorphous hippocampi bilaterally | MRI: thick corpus callosum, non-specific white matter anomalies of the deep white matter, bilateral and parietal, and of splenium of corpus callosum. | MRI: thick corpus callosum, high bilateral signal intensity in frontal subcortical region |

| MRS (spectroscopy): in white matter strongly increased total NAA (not in cortex) | ||||

| Seizures | At age 19–21 months three febrile seizures, seizures with awareness impairment and myoclonic seizures | Starting age 6 y, atonic, tonic-clonic seizures | One typical febrile seizure (age not known) | Starting age 1.5 y, focal epilepsy |

| EEG | Irregular basal activity at 6–8 Hz, intermittent beta wave activity, focus in right hemispheric region centroparietal and frontotemporal, spike waves occipital left, focal morphology, without generalization | High-amplitude paroxysmal discharges at the vertex | NA | Sharp waves in frontotemporal regions |

| Additional features/notes | NA | NA | CSF normal, tremor onset at 10 y, positional tremor and tremor of tongue, no intention tremor, progressive tremor, no pyramidal signs | NA |

Percentiles and standard deviations (SD) were calculated using https://www.pedz.de. CPAP = continuous positive airway pressure; HC = head circumference; IPPV = intermittent positive pressure ventilation; IRDS = infant respiratory distress syndrome; MRS = magnetic resonance spectroscopy; NA = not available; NAA = N-acetyl aspartate; NICU = neonatal intensive care unit.

Variants Leu470Arg, Ser133Pro and Ser110Thr are located in the interface between the inhibitory switch domain and the catalytic domain (Fig. 1). In each variant, the wild-type residue is replaced by a bulkier amino acid resulting in steric problems (‘clashes’) with adjacent amino acids, which destabilize the autoinhibitory domain and its interaction with the catalytic domain. Introducing arginine at p.Leu470, proline at p.Ser133, and threonine at p.Ser110 reduces binding by 1.76 kcal/mol, 1.26 kcal/mol, and 0.99 kcal/mol, respectively. The fourth variant, Pro121Ser, is located in the PAK1 dimer interface formed by the inhibitory switch domains of both subunits (Fig. 1 and Supplementary Fig. 1) and weakens binding by 2.30 kcal/mol. As a reference, an energy change of 1.36 kcal/mol corresponds to a reduction in binding affinity by one order of magnitude indicating that all three variants significantly destabilize the interaction between the inhibitory switch and the catalytic domain. In addition, the Pro121Ser variant is also expected to destabilize the autoinhibitory conformation of the switch domain itself: the rigid Pro121 with its cyclic sidechain is involved in the formation of a kink between two α-helices (Fig. 2K), which is expected to become more flexible in the Ser121 variant. The inhibitory switch domain has been described as the core of the autoregulatory fragment, which appears to inhibit the kinase with one surface and anchor the dimer contact with another. Conformational changes in this highly conserved protein domain are likely to affect protein function. A loss of stability in the autoinhibitory domain, thereby reducing autoinhibition would be supportive of a gain-of-function mode of the observed genetic variants. A PAK1 variant in the inhibitory switch domain, Leu107Phe, is already known to prevent the interaction between the N-terminal regulatory portion and catalytic domain, leading to kinase activation (Brown et al., 1996).

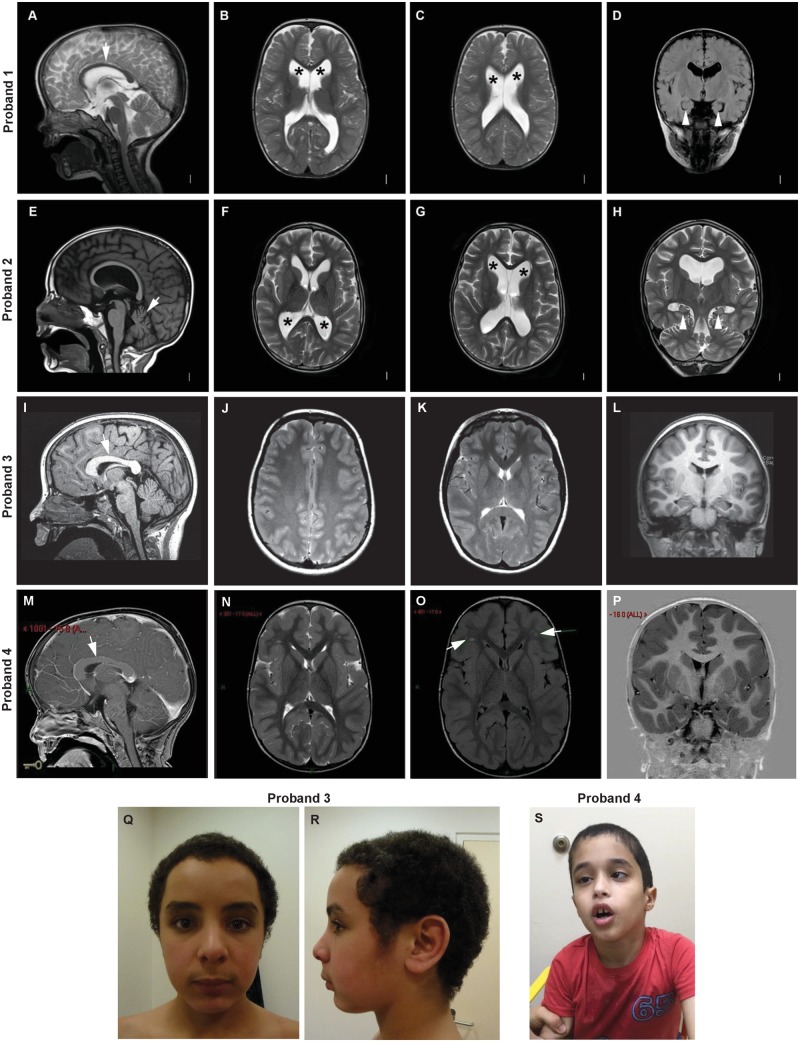

Figure 2.

Brain MRI and facial features of individuals with heterozygous PAK1 mutation. Brain MRIs of Proband 1 at age 2 years (A–D), Proband 2 at age 14 years (E–H), Proband 3 at age 12 years (I–L) and Proband 4 at age 8 years (M–P). Macrocephaly was caused by megalencephaly with or without accompanying ventriculomegaly. (A) T2 mid-sagittal image showing a thin corpus callosum (arrow). (B and C) T2 axial images showing ventriculomegaly (asterisks). (D) T1 coronal image showing globular and mildly amorphous hippocampi bilaterally. (E) T1 mid-sagittal image showing a thin corpus callosum and cerebellar atrophy with widening of the sulci (arrow). (F and G) T2 axial images showing ventriculomegaly (asterisks). (H) T2 coronal image showing mildly small and amorphous hippocampi bilaterally. (I) T1 mid-sagittal image showing a thick corpus callosum (arrow). (J and K) T2 axial images showing normal lateral ventricles. The white matter signal is slightly hyperintense in the posterior white matter, including the splenium (also present on FLAIR images, not shown). (L) T1 coronal image showing normal volume and position of the hippocampi. At proton MR spectroscopy, N-acetyl aspartate was elevated (not shown). These findings were unchanged 9 months later. (M) T1 mid-sagittal image showing macrocephaly and a thick corpus callosum (arrow). (N) T2 axial image showing normal size of the lateral ventricles. (O) FLAIR axial image showing small foci of abnormal signal in frontal white matter may be related to old insult. (P) T1 coronal image showing normal anatomy of the hippocampi. (Q and R) Photographs of Proband 3 at age 14 years with macrocephaly. (S) Photograph of Proband 4 at age 8 years with macrocephaly, facial muscular hypotonia and strabismus.

Discussion

PAK1 is a family member of the serine/threonine p21-activating (PAK) kinases composed of six known members in humans, PAK1–6. These proteins are critical effectors that link RhoGTPases to cytoskeleton reorganization and nuclear signalling and other intracellular processes (Manser et al., 1998; Zhao and Manser, 2012; Rane and Minden, 2014). Both PAK1 and PAK3 have been reported to control brain size through coordinating neuronal complexity and synaptic properties (Huang et al., 2011). Nonsense and missense variants that are thought to decrease autophosphorylation and activation of PAK3 have been described in males with X-linked recessive developmental delay (MIM: 300558). Recently, two probands with a neurodevelopmental disorder and de novo missense variants in PAK1 have been described. Their phenotype is similar to the phenotype presented by our probands with developmental delay, macrocephaly, seizures, and ataxic gait (Harms et al., 2018). The described variants p.(Tyr131Cys) and p.(Tyr429Cys) are located in the autoinhibitory and kinase domains of PAK1 similarly to the de novo variants presented in our study. Harms et al. (2018) furthermore showed that both variants lead to significantly reduced dimerization, providing evidence for a gain-of-function pathomechanism. Our results on the location of variants and the predicted effects on the protein provide additional evidence for this pathomechanism.

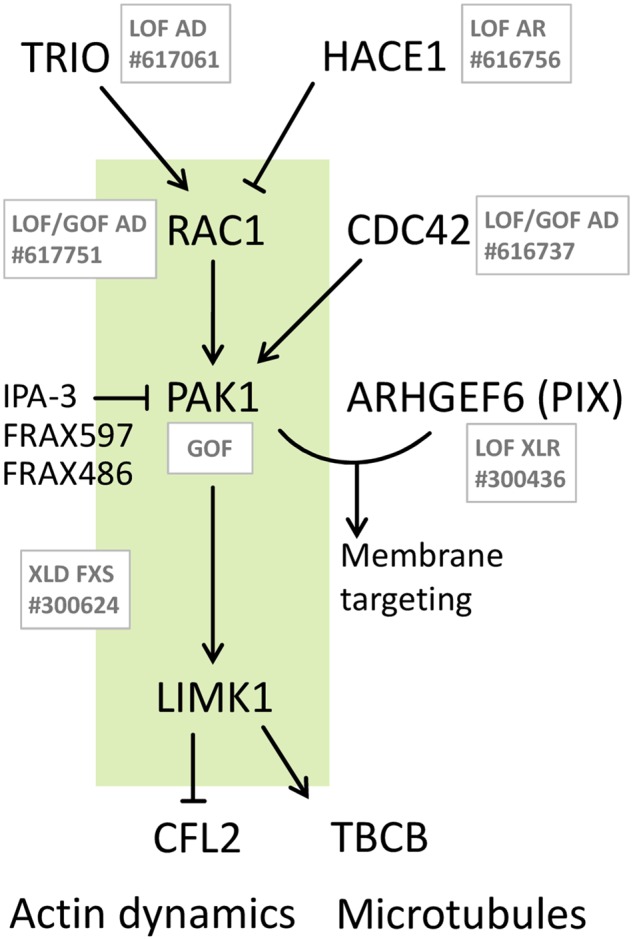

PAK1 is central to a well-described signalling pathway and an involvement in neurodevelopmental disorders was also described for other members of the pathway. Interacting partners of PAK1, especially the PAK1 activators RAC1 and CDC42, have been associated with developmental syndromes (Fig. 3 and Supplementary Table 2). De novo pathogenic missense RAC1 variants are associated with varying degrees of developmental delay, brain malformations, and additional phenotypes in autosomal dominant mental retardation 48 (MIM: 617751). Notably, of the seven reported affected individuals, two were macrocephalic; however, without a clear effect of protein activation. Pathogenic, heterozygous de novo or familial variants in CDC42 cause a highly heterogeneous developmental disorder (MIM: 616737). Some individuals with CDC42 variants showed a broad forehead; however again, carrying both activating and deactivating variants.

Figure 3.

Involvement of the PAK1 pathway in developmental phenotypes. RAC1 and CDC42 are direct activators, TRIO and HACE1 are indirect (via RAC1) regulators of PAK1. ARHGEF6 binds PAK1 for regulation of neurite outgrowth. PAK1 activates LIMK1, the regulator of PAK1 downstream effectors cofilin (CFL2) and tubulin cofactor B. Disorders associated with deactivating and/or activating variants for each gene are indicated in grey with the respective mode of inheritance given (see Supplementary Table 2 for details and phenotypic overlap). Green shaded box indicates activation of RAC1-PAK1-LIMK1 pathway in FXS, where macrocephaly also occurs. Currently available inhibitors of PAK1 are indicated.

Variants in TRIO and HACE1, known interactors of RAC1, are mainly reported as loss-of-function variants (MIM: 617061 and MIM: 616756). Notably, the PAK1-pathway is presumably activated in HACE1 deficiency neurodevelopmental syndrome (Hollstein et al., 2015) and the disorder resembles many of the symptoms described in this study, excluding macrocephaly, though one HACE1 patient had a large head circumference at birth (Supplementary Table 2). To determine other interactors of PAK1 we identified genes that show an expression associated with that of PAK1 and that code for proteins that physically interact with PAK1 (Supplementary Fig. 2). Additionally ARHGEF6 has been associated with a neurodevelopmental disorder (MIM: 300436). ARHGEF6 encodes the Rac/Cdc42 guanine nucleotide exchange factor 6 (PIX) (Manser et al., 1998), which can bind to PAK1 for the mediation of neurite outgrowth (Rane and Minden, 2014). A role of PAK1 in neuronal growth is also supported by MRI data of our probands. N-acetyl aspartate (NAA) is a key metabolite and marker of intact neurons. Increased total levels of NAA were detected in the MRI of Proband 3 and could possibly be related to the increased growth of neurons as a cause of megalencephaly in PAK1-related disorders. Amorphous hippocampi were present in two of four probands (Probands 1 and 2). It has been shown previously that PAK1 is critical in hippocampal synaptic plasticity by the regulation of cofilin activity and the actin cytoskeleton (Asrar et al., 2009). Hence, altered PAK1 activity may result in morphological changes of hippocampi, a feature that could be tested in future patients.

PAK1 is highly expressed in the human cerebellum and cortex and studies have described its role in neuronal migration by activating its downstream targets: LIMK1, cofilins and tubulin cofactor B (Sells et al., 1997; Delorme et al., 2007; Martinelli et al., 2018). PAK1 phosphorylation of tubulin cofactor B is essential for the polymerization of new microtubules, which is important for building and re-building neuronal structures (Edwards et al., 1999; Vadlamudi et al., 2005). PAK1 activates LIMK1 that plays a critical role in dendritic spine morphogenesis and brain function by phosphorylation and deactivation of cofilin (Meng et al., 2002). Cofilin can directly bind to actin filaments and promote their disassembly, needed for the reorganization of actin networks during neuronal growth (Chen et al., 2011). Consequently, increased activity of PAK1 in our probands would lead to increased activity of LIMK and thereby reduced actin dynamics via cofilin.

Recently, it was shown that the inherited intellectual disability and autism-associated FXS (MIM: 300624) is characterized by activated PAK1 (Pyronneau et al., 2017). Intriguingly, the characteristic loss of the mRNA-binding protein FMR1 increased the abundance and activity of Rac1 in mice. Rac1 activated the kinases Pak1 and Limk1, which inactivated cofilin, thus preventing actin depolymerization dynamics (Hayashi et al., 2007; Pyronneau et al., 2017). Both macrocephaly and seizures are also typically present in FXS, underscoring a similarity of phenotypes in patients with mutations in PAK1 and FXS.

Another piece of evidence supporting a gain-of-function mechanism for the identified variants in our patients is that PAK1 homozygous knockout (Pak1−/−) mice appear to be viable with no gross abnormalities. Human and mouse PAK1 genes are extremely well conserved, being 98% identical. Pak1−/− mice have some metabolic abnormal phenotypes, mainly increased blood urea levels, increased triglycerides, decreased lean body mass and decreased bone mineral content, and decreased neutrophils; however, no neurodevelopmental abnormalities or abnormal head size were reported (http://www.mousephenotype.org/data/genes/MGI:1339975). The fact that loss-of-function variants of PAK1 are tolerated in human populations (pLI = 0.67) (Karczewski et al., 2016) also indicates that this may not represent a prevailing pathomechanism of PAK1-associated disease.

Several inhibitors of PAK1 are currently under development and comprise ATP-competitive inhibitors, such as FRAX597 and FRAX486, which block ATP binding at the catalytic domain of PAK1 (Sampat and Minden, 2018). Dibenzodiazepines inhibit PAK1 by preventing its autophosphorylation (Karpov et al., 2015). If PAK1-associated disease proves to exhibit a gain-of-function mechanism, novel options for the treatment of affected patients could arise.

The importance of PAK1 in neuronal growth and structure, the positions and amino acids affected by the four identified genetic variants and their predicted effects on the protein, the strongly overlapping phenotypes of the affected individuals, as well as previously published data on other members of the PAK1-associated pathway allow us to consider that the de novo variants in PAK1 discovered in this study are the cause of a neurodevelopmental disorder characterized by intellectual disability with macrocephaly and seizures.

Web resources

Genematcher, https://genematcher.org/

GnomAD, http://gnomad.broadinstitute.org/

VARVIS, https://www.limbus-medtec.com/

UCSC Genome Browser, https://genome.ucsc.edu/

HGMD, https://portal.biobase-international.com/cgi-bin/portal/login.cgi?redirect_url=/hgmd/pro/start.php?

PolyPhen-2, http://genetics.bwh.harvard.edu/pph2/

MutationTaster, http://www.mutationtaster.org/

CADD, http://cadd.gs.washington.edu/score

R2, https://hgserver1.amc.nl/cgi-bin/r2/main.cgi

NCBI Pubmed, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/

Pedz, https://www.pedz.de

Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man, http://www.omim.org/

Genemania, https://genemania.org

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank the families and referring physicians for their participation in this study. We thank Julia Hentschel for technical assistance.

Glossary

Abbreviation

- FXS

fragile X syndrome

Funding

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS) under award number K08NS092898 and Jordan’s Guardian Angels (to G.M.). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors, and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. The funding sources had no role in the design and conduct of the study, collection, management, analysis and interpretation of the data, preparation, review or approval of the manuscript, or decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Competing interests

C.G-J. is a full-time employee of the Regeneron Genetics Center from Regeneron Pharmaceuticals Inc. and receives stock options as part of compensation. A.C. and C.M. are employed by and receive a salary from ARUP Laboratories. P.B-T. is a consultant to ARUP Laboratories. The other authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Asrar S, Meng Y, Zhou Z, Todorovski Z, Huang WW, Jia Z. Regulation of hippocampal long-term potentiation by p21-activated protein kinase 1 (PAK1). Neuropharmacology 2009; 56: 73–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boycott KM, Rath A, Chong JX, Hartley T, Alkuraya FS, Baynam G, et al. International cooperation to enable the diagnosis of all rare genetic diseases. Am J Hum Genet 2017; 100: 695–705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown JL, Stowers L, Baer M, Trejo J, Coughlin S, Chant J. Human Ste20 homologue hPAK1 links GTPases to the JNK MAP kinase pathway. Curr Biol 1996; 6: 598–605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S-Y, Huang P-H, Cheng H-J. Disrupted-in-schizophrenia 1–mediated axon guidance involves TRIO-RAC-PAK small GTPase pathway signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci 2011; 108: 5861–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Ligt J, Willemsen MH, van Bon BWM, Kleefstra T, Yntema HG, Kroes T, et al. Diagnostic exome sequencing in persons with severe intellectual disability. N Engl J Med 2012; 367: 1921–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delorme V, Machacek M, DerMardirossian C, Anderson KL, Wittmann T, Hanein D, et al. Cofilin activity downstream of Pak1 regulates cell protrusion efficiency by organizing lamellipodium and lamella actin networks. Dev Cell 2007; 13: 646–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards DC, Sanders LC, Bokoch GM, Gill GN. Activation of LIM-kinase by Pak1 couples Rac/Cdc42 GTPase signalling to actin cytoskeletal dynamics. Nat Cell Biol 1999; 1: 253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harms FL, Kloth K, Bley A, Denecke J, Santer R, Lessel D, et al. Activating mutations in PAK1, encoding p21-activated kinase 1, cause a neurodevelopmental disorder. Am J Hum Genet 2018; 103: 579–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi ML, Rao BS, Seo J-S, Choi H-S, Dolan BM, Choi S-Y, et al. Inhibition of p21-activated kinase rescues symptoms of fragile X syndrome in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci 2007; 104: 11489–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollstein R, Parry DA, Nalbach L, Logan CV, Strom TM, Hartill VL, et al. HACE1 deficiency causes an autosomal recessive neurodevelopmental syndrome. J Med Genet 2015; 52: 797–803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang W, Zhou Z, Asrar S, Henkelman M, Xie W, Jia Z. p21-Activated kinases 1 and 3 control brain size through coordinating neuronal complexity and synaptic properties. Mol Cell Biol 2011; 31: 388–403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karczewski KJ, Weisburd B, Thomas B, Solomonson M, Ruderfer DM, Kavanagh D, et al. The ExAC browser. Displaying reference data information from over 60 000 exomes. Nucl Acids Res 2016; 45: D840–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karpov AS, Amiri P, Bellamacina C, Bellance M-H, Breitenstein W, Daniel D, et al. Optimization of a dibenzodiazepine hit to a potent and selective allosteric PAK1 inhibitor. ACS Med Chem Lett 2015; 6: 776–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kircher M, Witten DM, Jain P, O’roak BJ, Cooper GM, Shendure J. A general framework for estimating the relative pathogenicity of human genetic variants. Nat Genet 2014; 46: 310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lei M, Lu W, Meng W, Parrini M-C, Eck MJ, Mayer BJ, et al. Structure of PAK1 in an autoinhibited conformation reveals a multistage activation switch. Cell 2000; 102: 387–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lek M, Karczewski KJ, Minikel EV, Samocha KE, Banks E, Fennell T, et al. Analysis of protein-coding genetic variation in 60,706 humans. Nature 2016; 536: 285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manser E, Loo T-H, Koh C-G, Zhao Z-S, Chen X-Q, Tan L, et al. PAK kinases are directly coupled to the PIX family of nucleotide exchange factors. Mol Cell 1998; 1: 183–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinelli S, Krumbach OHF, Pantaleoni F, Coppola S, Amin E, Pannone L, et al. Functional dysregulation of CDC42 causes diverse developmental phenotypes. Am J Hum Genet 2018; 102: 309–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maulik PK, Mascarenhas MN, Mathers CD, Dua T, Saxena S. Prevalence of intellectual disability. A meta-analysis of population-based studies. Res Dev Disabil 2011; 32: 419–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng Y, Zhang Y, Tregoubov V, Janus C, Cruz L, Jackson M, et al. Abnormal spine morphology and enhanced LTP in LIMK-1 knockout mice. Neuron 2002; 35: 121–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parrini MC, Lei M, Harrison SC, Mayer BJ. Pak1 kinase homodimers are autoinhibited in trans and dissociated upon activation by Cdc42 and Rac1. Mol Cell 2002; 9: 73–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pettersen EF, Goddard TD, Huang CC, Couch GS, Greenblatt DM, Meng EC, et al. UCSF Chimera—a visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J Comput Chem 2004; 25: 1605–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pirruccello M, Sondermann H, Pelton JG, Pellicena P, Hoelz A, Chernoff J, et al. A dimeric kinase assembly underlying autophosphorylation in the p21 activated kinases. J Mol Biol 2006; 361: 312–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pyronneau A, He Q, Hwang J-Y, Porch M, Contractor A, Zukin RS. Aberrant Rac1-cofilin signaling mediates defects in dendritic spines, synaptic function, and sensory perception in fragile X syndrome. Sci Signal 2017; 10: eaan0852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rane CK, Minden A. P21 activated kinases. Structure, regulation, and functions. Small GTPases 2014; 5: e28003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sampat N, Minden A. Inhibitors of the p21 activated kinases. Curr Pharmacol Rep 2018; 4: 238–49. [Google Scholar]

- Sells MA, Knaus UG, Bagrodia S, Ambrose DM, Bokoch GM, Chernoff J. Human p21-activated kinase (Pak1) regulates actin organization in mammalian cells. Curr Biol 1997; 7: 202–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trujillano D, Bertoli-Avella AM, Kandaswamy KK, Weiss MER, Köster J, Marais A, et al. Clinical exome sequencing. Results from 2819 samples reflecting 1000 families. Eur J Hum Genet 2017; 25: 176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vadlamudi RK, Barnes CJ, Rayala S, Li F, Balasenthil S, Marcus S, et al. p21-activated kinase 1 regulates microtubule dynamics by phosphorylating tubulin cofactor B. Mol Cell Biol 2005; 25: 3726–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vissers LE, Gilissen C, Veltman JA. Genetic studies in intellectual disability and related disorders. Nature Rev Genet 2016; 17: 9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong P, Zhang C, Zheng W, Zhang Y. BindProfX. Assessing mutation-induced binding affinity change by protein interface profiles with pseudo-counts. J Mol Biol 2017; 429: 426–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Z-S, Manser E. PAK family kinases. Physiological roles and regulation. Cell Logist 2012; 2: 59–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and/or its Supplementary material.