Abstract

Introduction

There is evidence that Yoga may be helpful as an aid for smoking cessation. Yoga has been shown to reduce stress and negative mood and may aid weight control, all of which have proven to be barriers to quitting smoking. This study is the first rigorous, randomized clinical trial of Yoga as a complementary therapy for smokers attempting to quit.

Methods

Adult smokers (N = 227; 55.5% women) were randomized to an 8-week program of cognitive-behavioral smoking cessation and either twice-weekly Iyengar Yoga or general Wellness classes (control). Assessments included cotinine-verified 7-day point prevalence abstinence at week 8, 3-month, and 6-month follow-ups.

Results

At baseline, participants’ mean age was 46.2 (SD = 12.0) years and smoking rate was 17.3 (SD = 7.6) cigarettes/day. Longitudinally adjusted models of abstinence outcomes demonstrated significant group effects favoring Yoga. Yoga participants had 37% greater odds of achieving abstinence than Wellness participants at the end of treatment (EOT). Lower baseline smoking rates (≤10 cigarettes/day) were also associated with higher likelihood of quitting if given Yoga versus Wellness (OR = 2.43, 95% CI = 1.09% to 6.30%) classes at EOT. A significant dose effect was observed for Yoga (OR = 1.12, 95% CI = 1.09% to 1.26%), but not Wellness, such that each Yoga class attended increased quitting odds at EOT by 12%. Latent Class Modeling revealed a 4-class model of distinct quitting patterns among participants.

Conclusions

Yoga appears to increase the odds of successful smoking abstinence, particularly among light smokers. Additional work is needed to identify predictors of quitting patterns and inform adjustments to therapy needed to achieve cessation and prevent relapse.

Implications

This study adds to our knowledge of the types of physical activity that aid smoking cessation. Yoga increases the odds of successful smoking abstinence, and does so in a dose-response manner. This study also revealed four distinct patterns of smoking behavior among participants relevant to quitting smoking. Additional work is needed to determine whether variables that are predictive of these quitting patterns can be identified, which might suggest modifications to therapy for those who are unable to quit.

Introduction

Vigorous, aerobic exercise is an effective aid for smoking cessation as it reduces postcessation weight gain,1,2 improves mood, and reduces cigarette cravings and withdrawal symptoms,3–7 offering significant benefits for smokers trying to quit by directly addressing fears of weight gain and ameliorating the physiological and affective symptoms of nicotine withdrawal.7,8

Yoga may offer additional benefits beyond those seen for standard aerobic exercise. Yoga has been shown to improve mood and reduce stress through the practice of asanas (Yoga postures), pranayama (breathing exercises), and seated meditation.9,10 Yoga also enhances mindfulness11—the purposeful direction of attention to present-moment experiences (sensations, perceptions, and thoughts) in a nonjudgmental way.12 Increases in mindfulness are associated with reductions in perceived stress, psychological distress, and cognitive reactivity.13,14 Mindfulness may also reduce symptoms of nicotine withdrawal, improve coping with cravings, and increase the cognitive deliberation needed to make effective choices to avoid smoking in tempting situations.11,15,16 Thus, Yoga may have special relevance for smokers who are trying to quit.9,15,16 Yoga practice also improves weight control.17–22 By addressing barriers such as stress, cravings, and weight concerns, and improving mindfulness, Yoga has some potential as an effective complementary therapy for smoking cessation. This study investigates the efficacy of Yoga as a complementary therapy for smoking cessation in a rigorously designed randomized prospective clinical trial. We hypothesized that participants given the Yoga intervention would show a significantly higher abstinence rates compared to a control condition.

Methods

Study Design Overview

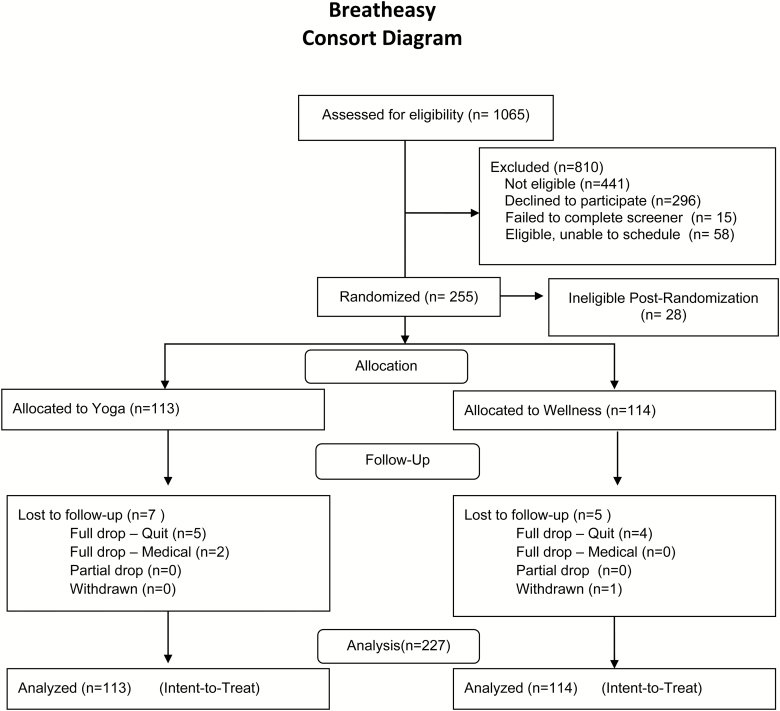

Adult smokers were randomly assigned in a 1:1 ratio to an 8-week program of either (1) Yoga or (2) general Wellness, which controlled for contact time and participant burden. In both programs, participants met for 1 hour, twice weekly. Participants also attended 1-hour weekly of group-based smoking cessation counseling. Smoking abstinence was measured at the end of treatment (EOT), and at 3- and 6-month follow-ups. A detailed description of the study design and procedures has been published elsewhere.23 Recruitment and follow-up retention are presented in the consort diagram (Figure 1). All sessions were conducted at a university-affiliated hospital in New England.

Figure 1.

Consort diagram.

Interventions

Smoking Cessation Counseling

This intervention consisted of group-based cognitive-behavioral therapy for smoking cessation delivered by PhD-level psychologists.23 Session content was similar to that used in our previous studies1,4,24 and included planning for the program’s targeted quit day (week 4), handling smoking triggers, coping with cravings, and managing withdrawal. A study manual was used to ensure that topics were covered consistently across study arms and multiple cohorts. All sessions were audio-recorded and coded to ensure treatment fidelity.

Yoga Intervention

This study used Iyengar Yoga25 because it emphasizes postural alignment and the use of props (eg, blocks and straps) to facilitate learning and reduce injury risk. Classes included 5 minutes of pranayama, 45 minutes of dynamically linked asanas, and 5–10 minutes of resting meditation. Classes were conducted by certified Iyengar instructors with more than 15 years’ experience. A manual was used to ensure consistent program delivery. Handouts showing the asanas and sequence used for the current week’s practice were given to participants weekly to encourage home practice.

Wellness Control

Group Wellness classes followed a format used in previous studies1,24 and consisted of videos, lectures, and demonstrations on a variety of health topics (eg, cancer screenings, sleep hygiene, and healthy diet) followed by a discussion guided by the study Wellness counselor or other health care professional (eg, sleep expert).

Recruitment, Screening, and Randomization Procedures

Advertisements were placed on local radio stations and Web sites. Flyers were posted at physician’s offices and retail outlets. Advertisements emphasized the smoking cessation program and explained that participants would also be randomized to a Wellness or Yoga program. Callers were screened for eligibility by research assistants and were excluded if they were pregnant, had a body mass index of more than 40 kg/m2, smoked less than 5 cigarettes/day, were currently enrolled in a quit-smoking program, were using medications to quit smoking, or had a medical condition that might make participation in Yoga difficult or potentially hazardous (eg, heart failure, ischemia, and hypertension).

Eligible individuals attended an orientation session to learn about study details and expectations. After providing written consent and completing baseline assessments, participants were randomized using a permuted block randomization stratified on gender and level of nicotine dependence (procedural details described elsewhere).23 All procedures and materials were approved by the Miriam Hospital Clinical Research Review Board (IRB registration no.0000482).

Assessments

Assessments were obtained by research assistants blind to randomization assignment. Participants were compensated $30 and $50 for completing the 3- and 6-month follow-ups, respectively.

Smoking Outcomes

Research assistants collected data weekly on participant class attendance, smoking rate (cigarettes per day), quit status, quit attempts, and use of medications. Self-reports of 7 days of nonsmoking were verified weekly by exhaled carbon monoxide (<10 ppm indicates abstinence for the previous 12–24 hours)26 and by saliva cotinine (<15 mg/mL) at EOT (week 8) and all follow-ups.27 Participants reporting 7-day point prevalence abstinence (7PPA) at EOT and follow-up were considered continuously abstinent.

Smoking-Related Covariates

At baseline, participants completed a 25-item questionnaire concerning their smoking history, including smoking rate, previous quit attempts, and use of medications. At baseline and all follow-ups, participants were assessed for nicotine dependence (Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence),28 and motivation to quit smoking, confidence in quitting, and readiness to quit using three items answered on a 10-point Likert scale from “not at all” to “extremely.”29

Other Covariates

Demographic information (eg, age, gender, and ethnicity) was collected at baseline along with measurements of height and weight.

Analyses

Baseline measures were summarized using descriptive statistics, and between-group differences in baseline characteristics were tested.30 Potential differences between cohorts in baseline characteristics were explored using parametric (analysis of variance) and nonparametric (chi-square) tests as appropriate.

Using a series of longitudinal models implemented with generalized estimating equations with robust standard errors, we tested the effect of randomization on binary smoking outcomes (7PPA and continuous abstinence) over time (smoking status at week 5 through follow-up) controlling for potential confounders including contamination risk (defined as any Wellness participant who reported participation in Yoga during the 8-week treatment). Models included effects of intervention, time, time × intervention, as well as potential confounders. Data were clustered within participant within cohort, and standard errors were adjusted accordingly. We explored potential moderating effects of smoking rate at baseline by including main effects of smoking rate, and all two- and three-way interactions between smoking rate, time, and treatment group.

We tested the effects of randomization on mean smoking rate over time using a longitudinal mixed effects model in which smoking rates postquit date (week 5) through follow-up were regressed on time, group, and time × group. Models adjusted for confounders including contamination risk and baseline smoking rate, and included a subject-specific intercept to adjust for repeated measures of the outcome within participant. Potential cohort effects were also explored. As with our primary outcomes, we explored potential moderating effects of baseline smoking rate on treatment effects.

Using Latent Class Models (LCMs), we sought to identify smoking patterns during the treatment period (exploratory analysis). The outcome of interest was self-reported 7PPA from quit date through EOT, with cotinine validation at week 8. LCMs assume the population is made up of a finite number of patterns (smoking patterns in this case). This technique reduces participant-level data from a vector of up to 8 weeks of data to a single class, corresponding to their most likely pattern of smoking behavior. Class (pattern) provides an objective grouping that can be used as a predictor or outcome in subsequent analyses. To identify the number of classes supported by the data, we fit a series of LCMs ranging from 2 to 6 classes and identified the model that minimized the Bayesian information criteria value (which maximizes fit). The optimal solution was a 4-class model (significant model fit and significantly lowest Bayesian information criteria), which is presented later. Classes were compared based on baseline characteristics, randomized group, smoking rates at 3- and 6-month follow-up, and baseline motivational variables (ie, motivation, readiness, and confidence) using chi-square tests and analysis of variance as appropriate. Finally, we explored potential dose effects both within and across groups using a similar modeling strategy.

All analyses were conducted on the intent-to-treat sample (N = 227). Models used likelihood-based approaches to estimation and thus made use of all available data without directly imputing missing data. Results were compared to the conservative assumption that missing equals smoking (in the case of binary outcomes) and did not differ substantially from the maximum likelihood estimation. All analyses were run using SAS v. 9.3 and R, and significance value was set at α = .05 a priori.

Results

Sample

Among participants (N = 227) randomized at baseline, 55.5% were women, 72.3% had attended at least some college, 42.3% were married or partnered, and 55.9% were employed full time. Mean age was 46.2 (SD = 12.0) years. Mean smoking rate at baseline was 17.0 (SD = 7.8) cigarettes/day. There were no significant between-group differences in baseline characteristics (Table 1), and no differences between study cohorts. Overall, the study retention rate was 94.7% through final follow-up with no difference between groups (p > .05).

Table 1.

Participant Characteristics at Baseline by Intervention Group (N = 227)

| Variable | Overall, N = 227 | Yoga, n = 113 | Wellness, n = 114 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD), y | 46.2 (12.0) | 46.1 (12.0) | 46.4 (12.0) |

| Gender (female), No. (%) | 126 (55.5) | 67 (59.3) | 59 (51.8) |

| Race (white), No. (%) | 195 (85.9) | 102 (90.3) | 93 (81.6) |

| Hispanic/Latino, No. (%) | 8 (3.5) | 4 (3.5) | 4 (3.5) |

| Education level, No. (%) | |||

| High school graduate or less | 63 (27.8) | 31 (27.4) | 32 (28.1) |

| At least some college | 138 (60.8) | 66 (58.4) | 72 (63.2) |

| At least some graduate school | 26 (11.5) | 16 (14.2) | 10 (8.8) |

| Income ($), No. (%) | |||

| <11 500 | 32 (14.1) | 12 (10.6) | 20 (17.5) |

| 11 501–50 000 | 91 (40.1) | 45 (39.8) | 46 (40.4) |

| 50 001–100 000 | 71 (31.3) | 40 (35.4) | 31 (27.2) |

| >100 000 | 19 (8.4) | 11 (9.7) | 8 (7.0) |

| Don’t know/refuse | 14 (6.2) | 5 (4.4) | 9 (7.9)20 |

| Marital status, No. (%) | |||

| Single | 88 (38.8) | 50 (44.2) | 38 (33.3) |

| Single, live with partner | 34 (15.0) | 11 (9.7) | 23 (20.2) |

| Married | 62 (27.3) | 33 (29.2) | 29 (25.4) |

| Separated, divorced, widowed | 43 (18.9) | 19 (16.8) | 24 (21.1) |

| Employment status, No. (%) | |||

| Employed full time | 127 (55.9) | 66 (58.4) | 61 (53.5) |

| Employed part-time | 22 (9.7) | 15 (13.3) | 7 (6.1) |

| Unemployed | 47 (20.7) | 21 (18.6) | 26 (22.8) |

| Other | 31 (13.7) | 11 (9.7) | 20 (17.5) |

| BMI (baseline), mean (SD), kg/m2 | 27.3 (5.0) | 27.1 (4.7) | 27.6 (5.3) |

| Cigarettes per day (baseline), mean (SD) | 17.0 (7.8) | 16.9 (7.5) | 17.1 (8.1) |

| Readiness to quit, mean (SD) | 7.9 (1.8) | 8.0 (1.8) | 7.8 (1.8) |

| Confidence to quit, mean (SD) | 7.8 (1.9) | 7.8 (1.9) | 7.8 (1.9) |

| Motivated to quit, mean (SD) | 8.7 (1.4) | 8.7 (1.5) | 8.7 (1.5) |

| Fagerström score, mean (SD) | 4.9 (2.1) | 4.9 (2.1) | 4.9 (2.0) |

BMI = body mass index; SD = standard deviation. No significant between-group differences.

Smoking Outcomes

Longitudinal adjusted models indicate significant group effects favoring Yoga with respect to 7PPA at EOT (odds ratio [OR] = 1.37, 95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.07% to 2.79%). The odds of 7PPA at EOT were 37% higher for Yoga versus Wellness participants. Effects were no longer significant at 3- and 6- month follow-up (ps > .05). There were no significant effects of group on continuous abstinence (p = .52). Overall, 11.2% of participants had prolonged abstinence at 6 months, with no significant group effect (p = .92).

Moderating Effects

Exploration of the moderating effects of baseline smoking rate suggests there were significant effects of group on 7PPA at EOT among those with low smoking rates at baseline (≤10 cigarettes/day = 25th percentile; OR = 2.43, 95% CI = 1.09% to 6.30%). Among light smokers at baseline, the odds of 7PPA at EOT for Yoga were 2.43 times that of Wellness. There were no moderating effects of baseline smoking rate on continuous abstinence (p > .05).

Adjusted models indicate that Yoga participants were smoking significantly fewer cigarettes per day at EOT compared to Wellness (adjusting for baseline). Specifically, there was a 1.54 (standard error = 0.59, p = .01) difference in cigarettes per day favoring Yoga at EOT. This effect was most pronounced among those with higher smoking rates at baseline (≥20 cigarettes/day = 75th percentile). Among these individuals, those in Yoga smoked 2.66 fewer cigarettes per day at EOT compared to Wellness (standard error = 1.33, p = .04).

Patterns of Quitting Behavior

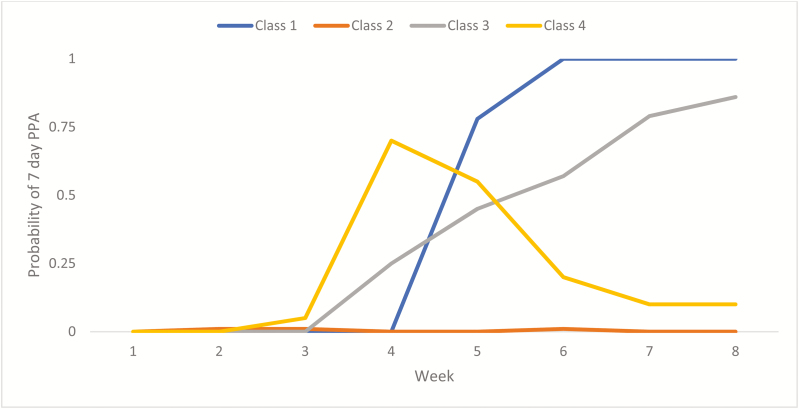

LCM analysis suggests a 4-class model is best supported by the data. Patterns show that 16% of participants quit by week 4 and had high probability of remaining quit through week 8 (Class 1: Quit Date Quitters). Most participants (71%) were not able to achieve abstinence (Class 2: Non-quitters), 5% of participants were slow and steady quitters such that the slope increased over time with high probability of being quit by EOT (Class 3: Slow Quitters), and 8% of participants had high probability of quitting on or before week 4 with a decline in odds of remaining quit thereafter (Class 4: Relapsers). These patterns are depicted in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Latent class Model (LCM) resulting patterns of quitting over time among all participants.

Participants randomized to Yoga were significantly more likely to be Quit Date Quitters or Slow Quitters compared to Wellness participants (p = .04). Both Quit Date Quitters and Slow Quitters (67.6% and 60%, respectively) were more likely to report 7PPA at 3 months than Non-quitters and Relapsers (2.2% and 14.3%, respectively). Although there were no significant between-class differences in baseline demographics (Table 2), there was a significant effect of baseline smoking rate on the distribution of classes. Specifically, light smokers (≤10 cigarettes/day) were significantly more likely to be Slow Quitters compared to other classes (p = .04).

Table 2.

Participant Demographics by Pattern

| Variable | Quit Date Quitters, n = 36 | Non-quitters, n = 162 | Slow Quitters, n = 12 | Relapsers, n = 17 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD), y | 49.47 (12.50) | 45.25 (11.41) | 48.33 (11.84) | 47.12 (15.48) |

| Gender (female), No. (%) | 18 (50.0) | 94 (58.0) | 6 (50.0) | 8 (47.1) |

| Race (white), No. (%) | 34 (94.4) | 147 (90.7) | 10 (83.3) | 15 (88.2) |

| Hispanic/Latino, No. (%) | 1 (2.8) | 7 (4.3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Education level, No. (%) | ||||

| High school graduate or less | 10 (27.8) | 48 (29.6) | 2 (16.7) | 3 (17.6) |

| At least some college | 18 (50.0) | 99 (61.1) | 9 (75.0) | 12 (70.6) |

| At least some graduate school | 8 (22.2) | 15 (9.3) | 1 (8.3) | 2 (11.8) |

| Income ($), No. (%) | ||||

| <11 500 | 2 (5.6) | 25 (15.4) | 3 (25.0) | 2 (11.8) |

| 11 501–50 000 | 16 (44.4) | 62 (38.3) | 6 (50.0) | 7 (41.2) |

| 50 001–100 000 | 12 (33.3) | 50 (30.9) | 2 (16.7) | 7 (41.2) |

| >100 000 | 5 (13.9) | 12 (7.4) | 1 (8.3) | 1 (5.9) |

| Don’t know/refuse | 1 (2.8) | 13 (8.0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Marital status, No. (%) | ||||

| Single | 14 (38.9) | 65 (40.1) | 4 (33.3) | 5 (29.4) |

| Single, live with partner | 3 (8.3) | 16 (16.0) | 2 (16.7) | 3 (17.6) |

| Married | 11 (30.6) | 43 (26.5) | 2 (16.7) | 6 (35.3) |

| Separated, divorced, widowed | 8 (22.2) | 28 (17.3) | 4 (33.3) | 3 (17.6) |

| Employment status, No. (%) | ||||

| Employed full time | 23 (63.9) | 87 (53.7) | 7 (58.3) | 10 (58.8) |

| Employed part-time | 3 (8.3) | 14 (8.6) | 2 (16.7) | 3 (17.6) |

| Unemployed | 4 (11.1) | 39 (24.1) | 2 (16.7) | 2 (11.8) |

| Other | 6 (16.7) | 22 (13.6) | 1 (8.3) | 2 (11.8) |

| BMI (baseline), mean (SD), kg/m2 | 27.54 (4.08) | 27.40 (5.11) | 28.88 (5.34) | 25.46 (4.98) |

| Cigarettes per day (baseline), mean (SD) | 15.75 (7.99) | 16.99 (7.81) | 14.75 (7.03) | 18.12 (8.28) |

| Fagerström score, mean (SD) | 4.69 (2.27) | 4.94 (2.02) | 5.17 (2.76) | 5.18 (1.67) |

BMI = body mass index; SD = standard deviation.

There were significant between-class differences in readiness and confidence in quitting (and a trend for motivation to quit) at baseline. Relapsers had highest mean scores on readiness to quit (9.18, SD = 1.07), and Slow Quitters had the lowest mean readiness scores (7.50, SD = 2.15) at baseline. However, Quit Date Quitters had significantly higher confidence to quit compared to other classes, and Slow Quitters had the lowest mean confidence scores: Quit Date Quitters = 8.56 (SD = 1.46), Non-quitters = 7.62 (SD = 1.92), Slow Quitters = 1.50 (SD = 1.98), Relapsers = 8.47 (SD = 1.97). Slow quitters and Relapsers trended toward higher motivation scores at baseline (9.25, SD = 1.06 and 9.29, SD = 1.05, respectively) compared to Quit Date Quitters (8.92, SD = 1.27) and Non-quitters (8.54, SD = 1.52). There were no other differences in baseline variables between classes (ps > .05).

Treatment Dose Effects

There was no significant difference in the average number of classes attended (of possible 24) during treatment between Yoga (mean = 16.49, SD = 5.92) and Wellness (mean = 16.61, SD = 7.42) participants (p > .05). Among Yoga participants, there was a significant association between total dose of treatment received and 7PPA (OR = 1.12, 95% CI = 1.09% to 1.26%), such that each additional session attended was associated with a 12% increase in the odds of being quit at EOT. There was no significant dose effect among Wellness participants (p > .05).

Home Practice

Home practice of Yoga was tracked weekly through 6-month follow-up. At EOT, 47% of Yoga participants reported practicing Yoga at home (an average of 2.56 days/week). At 3 months, Yoga participants reported an average of 90.00 min/week of Yoga (SD = 50.90) and 75.36 min/week of Yoga (SD = 74.25) at 6 months.

Discussion

This is the first large-scale randomized controlled trial to successfully recruit and retain adult smokers in the United States that examined Yoga as a complementary treatment for smoking cessation. This study compared Yoga to a Wellness control to complement standard smoking cessation counseling based on cognitive-behavioral therapy, a well-tested, effective intervention for tobacco cessation.31 The study design was stringent in that both groups were proved with a high-quality, intensive therapy for smoking cessation. Thus, we could test the relative efficacy of Yoga to a comparison arm that effectively controlled for contact time, attention, and subject burden.

Results indicated that in this sample, Iyengar Yoga was highly feasible and acceptable based on strong attendance and retention rates. Participation was enthusiastic as demonstrated by our 94.7% retention rate across both groups.

Longitudinally adjusted models showed significant results favoring Yoga. Participants in the Yoga group were 37% more likely to quit than those in Wellness group. Yoga also had differential effects between heavier and lighter smokers in that lighter smokers were over twice as likely to quit if given Yoga.

Although most participants did not achieve smoking abstinence, participants in both groups significantly decreased their daily cigarette consumption by the EOT. Yoga produced a greater reduction in smoking rate by EOT compared to Wellness, particularly among those who were heavier smokers at baseline. Thus, Yoga had a positive effect on smoking among all participants compared to controls. Those who were smoking fewer cigarettes at baseline were more likely to quit if they received Yoga, and heavy smokers were more likely to cut down, a positive step on the path to improved health and eventual cessation.

LCM revealed 4 distinct patterns of quitting behavior that differed significantly between treatment arms. Yoga participants were more likely to be represented in the two “successful” patterns of quitting: either those able to quit on the designated quit day (week 4) and remain quit, or those who experienced a gradual reduction in smoking rate leading to full abstinence by EOT. In contrast, Wellness participants were more likely to never achieve full abstinence or to quit early (before the designated quit day), and relapse to smoking before EOT. Future work is needed to identify whether these patterns can be predicted and treatment adjustments made for individuals likely to relapse early or never quit.

Results of this study also provide an intriguing hint that some variables or combination of variables may predict these patterns. Readiness, confidence, and motivation for quitting have been predictive of successful smoking cessation in multiple studies.32,33 However, in this study we saw noteworthy differences in the distribution of these constructs based on pattern of quitting. For example, Relapsers scored high on all three measures (readiness, confidence, and motivation), whereas Slow Quitters scored high on motivation, but lower on readiness and far lower in confidence. It is possible that other factors may predict which pattern an individual falls into and thus suggest options for enhanced treatment approaches. For example, it would be unsurprising if Relapsers were relatively low on mindfulness and/or high on impulsivity at program entry. If supported, a Yoga program emphasizing mindfulness training might address these deficits more intensely at the beginning and perhaps reduce the likelihood of early quitting that leads to quick relapse. Similarly, there is a substantial literature showing that comorbid affective symptoms such as anxiety and depression are associated with smoking and predictive of postcessation relapse.34,35 It may be fruitful to identify whether and how the patterns of quitting and non-quitting found in the present study may map onto these specific affective states as well as transdiagnostic markers of emotional vulnerability, such as anxiety sensitivity, low distress tolerance, and similar psycho-affective characteristics.

Limitations

Both treatment arms were labor-intensive for participants, requiring 3 hours weekly for 8 weeks. To enhance potential dissemination, it would be valuable to test whether a home-delivered Yoga program would be effective. Both arms were provided with a strong well-validated cognitive-behavioral therapy smoking cessation program, leading to higher abstinence rates than might be the seen in less intensive programs. The Wellness program was not a real-world comparison, in that smoking cessation programs are not typically paired with Wellness programs. However, this comparison was chosen to avoid any bias that might result from unequal subject burden between conditions. We did not use medications to aid smoking cessation although medications are the current standard of care.31 We were concerned that if Yoga produced a small positive effect on cessation, that effect might be effectively washed out by the addition of medications, which typically produce a doubling of effect size.31 To detect a potentially small intervention effect above and beyond the impact of medications would require a much larger sample. Individuals seeking a program like Yoga to aid them in quitting smoking may be disinclined to use medications, although there are currently no data to support or refute this. Similarly, many individuals cannot use or choose not to use quit-smoking medications because of cost, interactions with their other medications, or medical contraindications;36 therefore, we studied Yoga as a potential option for those who cannot or will not use medications for quitting.

Conclusions

Yoga appears to aid some smokers during quit attempts. Yoga may be particularly effective for lighter smokers, and higher doses of Yoga (eg, more frequent classes or programs of longer duration) may be most effective. Additional work is needed to determine whether we can identify predictors of quitting patterns and use this information to make adjustments to therapy in order to maximize treatment efficacy for each smoker.

Funding

Funding for this study was provided by a grant from the National Institutes of Health, National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health (R01 AT006948 to BB).

Declaration of Interests

The authors have no competing financial interests to declare.

References

- 1. Marcus BH, Albrecht AE, King TK, et al. . The efficacy of exercise as an aid for smoking cessation in women: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med. 1999;159(11):1229–1234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ussher MH, Taylor AH, Faulkner GE. Exercise interventions for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;(4):CD002295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Annesi JJ. Changes in depressed mood associated with 10 weeks of moderate cardiovascular exercise in formerly sedentary adults. Psychol Rep. 2005;96(3 Pt 1):855–862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bock BC, Marcus BH, King TK, Borrelli B, Roberts MR. Exercise effects on withdrawal and mood among women attempting smoking cessation. Addict Behav. 1999;24(3):399–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Dunn AL, Trivedi MH, O’Neal HA. Physical activity dose-response effects on outcomes of depression and anxiety. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2001;33(suppl 6):S587–S597; discussion 609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Matsouka O, Kabitsis C, Harahousou Y, Trigonis I. Mood alterations following an indoor and outdoor exercise program in healthy elderly women. Percept Mot Skills. 2005;100(3 Pt 1):707–715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ussher M, Nunziata P, Cropley M, West R. Effect of a short bout of exercise on tobacco withdrawal symptoms and desire to smoke. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2001;158(1):66–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Taylor AH, Katomeri M, Ussher M. Acute effects of self-paced walking on urges to smoke during temporary smoking abstinence. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2005;181(1):1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Li AW, Goldsmith CA. The effects of yoga on anxiety and stress. Altern Med Rev. 2012;17(1):21–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Shahab L, Sarkar BK, West R. The acute effects of yogic breathing exercises on craving and withdrawal symptoms in abstaining smokers. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2013;225(4):875–882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gard T, Brach N, Hölzel BK, Noggle JJ, Conboy LA, Lazar SW. Effects of a yoga-based intervention for young adults on quality of life and perceived stress: the potential mediating roles of mindfulness and self-compassion. J Posit Psychol. 2012;7(3):165–175. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kabat-Zinn J. Full Catastrophe Living: Using the Wisdom of Your Body and Mind to Face Stress, Pain, and Illness. New York, NY: Delta Trade; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Carmody J, Baer RA. Relationships between mindfulness practice and levels of mindfulness, medical and psychological symptoms and well-being in a mindfulness-based stress reduction program. J Behav Med. 2008;31(1):23–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Raes F, Dewulf D, Van Heeringen C, Williams JM. Mindfulness and reduced cognitive reactivity to sad mood: evidence from a correlational study and a non-randomized waiting list controlled study. Behav Res Ther. 2009;47(7):623–627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. McClernon FJ, Westman EC, Rose JE. The effects of controlled deep breathing on smoking withdrawal symptoms in dependent smokers. Addict Behav. 2004;29(4):765–772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ussher M, West R, Doshi R, Sampuran AK. Acute effect of isometric exercise on desire to smoke and tobacco withdrawal symptoms. Hum Psychopharmacol. 2006;21(1):39–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Bera TK, Rajapurkar MV. Body composition, cardiovascular endurance and anaerobic power of yogic practitioner. Indian J Physiol Pharmacol. 1993;37(3):225–228. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Emery CF, Blumenthal JA. Perceived change among participants in an exercise program for older adults. Gerontologist. 1990;30(4):516–521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kristal AR, Littman AJ, Benitez D, White E. Yoga practice is associated with attenuated weight gain in healthy, middle-aged men and women. Altern Ther Health Med. 2005;11(4):28–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Mahajan AS, Reddy KS, Sachdeva U. Lipid profile of coronary risk subjects following yogic lifestyle intervention. Indian Heart J. 1999;51(1):37–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Roland KP, Jakobi JM, Jones GR. Does yoga engender fitness in older adults? A critical review. J Aging Phys Act. 2011;19(1):62–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Schmidt T, Wijga A, Von Zur Mühlen A, Brabant G, Wagner TO. Changes in cardiovascular risk factors and hormones during a comprehensive residential three month kriya yoga training and vegetarian nutrition. Acta Physiol Scand Suppl. 1997;640:158–162. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Bock BC, Rosen RK, Fava JL, et al. . Testing the efficacy of yoga as a complementary therapy for smoking cessation: design and methods of the BreathEasy trial. Contemp Clin Trials. 2014;38(2):321–332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Marcus BH, King TK, Albrecht AE, Parisi AF, Abrams DB. Rationale, design, and baseline data for Commit to Quit: an exercise efficacy trial for smoking cessation among women. Prev Med. 1997;26(4):586–597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Iyengar BKS. BKS Iyengar Yoga: The Path to Holistic Health. New York, NY: DK Publishing; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hughes JR, Keely JP, Niaura RS, Ossip-klein DJ, Richmond RL, Swan GE. Measures of abstinence in clinical trials: issues and recommendations. Nicotine Tob Res. 2003;5(1):13–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Benowitz NL, Jacob P III, Ahijevych K, et al. . ; SRNT Subcommittee on Biochemical Verification. Biochemical verification of tobacco use and cessation. Nicotine Tob Res. 2002;4(2). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Heatherton TF, Kozlowski LT, Frecker RC, Fagerström KO. The Fagerström test for nicotine dependence: a revision of the Fagerström tolerance questionnaire. Br J Addict. 1991;86(9):1119–1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Bock BC, Morrow KM, Becker BM, et al. . Yoga as a complementary treatment for smoking cessation: rationale, study design and participant characteristics of the Quitting-in-Balance study. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2010;(10):14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Bock BC, Thind H, Dunsiger S, et al. . Who Enrolls in a Quit Smoking Program with Yoga Therapy?Am J Health Behav. 2017;41(6):740–749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Fiore MC, Jaen CR, Baker TB, et al. . Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence: 2008 Update. Clinical Practice Guideline. Rockville, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Borland R, Yong HH, Balmford J, et al. . Motivational factors predict quit attempts but not maintenance of smoking cessation: findings from the international tobacco control four country project. Nicotine Tob Res. 2010;12(suppl):S4–S11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Boudreaux ED, Sullivan A, Abar B, Bernstein SL, Ginde AA, Camargo CA Jr. Motivation rulers for smoking cessation: a prospective observational examination of construct and predictive validity. Addict Sci Clin Pract. 2012;7:8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Leventhal AM, Zvolensky MJ. Anxiety, depression, and cigarette smoking: a transdiagnostic vulnerability framework to understanding emotion-smoking comorbidity. Psychol Bull. 2015;141(1):176–212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Shiffman S, Paty JA, Gnys M, Kassel JA, Hickcox M. First lapses to smoking: within-subjects analysis of real-time reports. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1996;64(2):366–379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Vogt F, Hall S, Marteau TM. Understanding why smokers do not want to use nicotine dependence medications to stop smoking: qualitative and quantitative studies. Nicotine Tob Res. 2008;10(8):1405–1413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]