Abstract

Objectives The main purpose of this article is to estimate the trend and projection of cesarean section rates (CSRs) and explore correlations between CSRs with adverse maternal and perinatal outcomes, namely maternal mortality ratios (MMRs), rates of postpartum hemorrhage (PPH), neonatal mortality rates (NMRs), and birth asphyxia per 1,000 live births across all regions of Thailand.

Study design A secondary analysis of the hospital-based database of pregnant women and newborns under the Thai Universal Coverage Scheme between January 2009 and December 2017 was conducted.

Results Overall annual CSR significantly increased from 23.2% in 2009 to 32.5% in 2017. With the same rate of increase, the CSR of 59.1% was projected by the year 2030 that could be reduced to 30.0% if an annual rate of CS reduction of 1% was assumed using Joinpoint regression. The increasing CSRs were significantly correlated with higher MMRs ( r = 0.20, p = 0.03) and birth asphyxia ( r = 0.39, p < 0.001). The correlation trends were similar when the analyses were stratified by year in the majority of years. Overall correlations between CSRs and rates of PPH or NMRs were not statistically significant.

Conclusion CSRs in Thailand continuously increased and were correlated with adverse maternal and perinatal outcomes. More effort at the national level to reduce unnecessary CS is urgently required.

Keywords: cesarean section rates, maternal and perinatal outcomes, trend, Universal Coverage Scheme

Cesarean section (CS) is an essential operative obstetric for pregnant women facing emergent conditions. It is a procedure to prevent serious maternal and perinatal complications. 1 Even though the World Health Organization (WHO) recommends that national CS levels should not be greater than 15% 2 , a multicountry survey by the WHO found that the worldwide cesarean section rates (CSRs) had increased from 26.4% in 2004 to 2008 to 31.2% in 2010 to 2011. 3 In Thailand, the CSR increased from 17.4% in 2000 to 2008 4 to 32.7% in 2015 to 2016. 5

Although CSRs have increased, maternal and perinatal mortality or morbidity rates have not been proportionately reduced in which these are essential to be monitored. 6 7 8 Postpartum hemorrhage is one of common causes of maternal death and major obstetric complications that was shown to be more common in women underwent CS than vaginal delivery. 6 9 Similarly, birth asphyxia has been reported more common in women undergoing CS. 10 The information on CSR and these maternal and perinatal morbidities will be important evidences for the policy makers in individual countries to understand the CSR situation and these common maternal and perinatal morbidities.

In Thailand, there are three main public health insurance schemes, namely the Civil Servant Medical Benefit Scheme (CSMBS), Social Security Scheme (SSS), and Universal Coverage Scheme (UCS). All schemes cover the maternity services benefits. 11 The UCS managed by the National Health Security Office (NHSO) covers approximately three-fourths of the population (48 million). 12 A study showed that 96% of UCS population had completed high school or below as well as 73% were employed and the UCS adequately served the needs of beneficiaries for healthcare utilization. 13 Likewise, the findings from the national reproductive health survey showed high coverage of delivery by skilled birth attendance with very small socioeconomic and geographic disparities and the public sector played a majority role for maternity care. 14

Approximately 50% of population under UCS in Thailand are in the poor wealth quintiles that was higher than that of the population under the CSMBS and SSS. 15 A study in Korea found that women with low socioeconomic status were more vulnerable to adverse maternal and perinatal outcomes including CS regardless of a universal healthcare system. 16 All pregnant women and their babies under the UCS receive care at public health facilities free of charge. 17 To get reimbursement, the health facilities have to submit data of all pregnant women under the UCS to the NHSO; therefore, the number of women giving birth and their adverse maternal and perinatal outcomes have been reocrded. 15 This study aimed to estimate the trend and projection of the CSR and explore the correlations between CSRs and the maternal mortality ratios (MMRs), rates of postpartum hemorrhage (PPH), neonatal mortality rates (NMRs), and birth asphyxia rates over time across all regions of Thailand.

Materials and Methods

A secondary analysis of aggregate data of CSRs, MMRs, and rates of PPH, NMRs, and rates of birth asphyxia per 1,000 live births by health region from the database of the NHSO for the years of 2009 to 2017 was performed. The data from the sections on pregnancy, childbirth and the puerperium (code O), factors influencing health status and contact with health services (code Z), and certain conditions originating in the perinatal period (code P) of the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 10th version (ICD-10) were extracted. All in-patient data for the years 2009 to 2017 were available.

The exposure of interest in this analysis was CSR. Outcome measures were adverse maternal and perinatal outcomes including the MMRs and rates of PPH, NMRs, and rates of birth asphyxia per 1,000 live births.

CSR was calculated by dividing the number of women undergoing CS by the total number of women giving birth at all hospitals in each region of Thailand under UCS in NHSO database at the same period multiplied by 100. The number of women undergoing CS was extracted from the principle or secondary ICD-10 diagnoses of O82 or O842 and the ICD-9 740–744 or 7499 C-section procedures. Total number of women giving birth was extracted from the principle or secondary ICD-10 diagnoses of O80-O84.

MMR was calculated by dividing the number of maternal deaths by the number of live births in the same period multiplied by 100,000. Maternal death was defined as a woman who died during pregnancy, irrespective of the duration or site of the pregnancy, or within 6 weeks after termination of pregnancy from any cause related to or aggravated by the pregnancy or its management but not from accidental or incidental causes.

The number of maternal deaths was extracted from the principle or secondary ICD-10 diagnoses of O00-O95 or O98-O99, death on discharge status and reporting death within 30 days to the national vital registration. The number of live births was extracted from the secondary ICD-10 diagnoses of Z370, Z372, Z373, Z375, or Z376.

The rate of PPH was calculated by dividing the number of women with PPH by the total number of women giving birth in the hospitals during the same period multiplied by 100. The number of women with PPH was extracted from the principle or secondary ICD-10 diagnosis of O72.

NMR was calculated by dividing the number of live born neonates who died within 28 days of birth by the number of live births during the same period multiplied by 1,000. The number of live born neonates who died within 28 days of birth were extracted from the data of Thai Diagnosis Related Group and Death Registration.

Rate of birth asphyxia was calculated by dividing the number of live born infants with birth asphyxia using the principle or secondary ICD-10 diagnosis of P21 by the number of live births during the same period multiplied by 1,000.

Data were analyzed by R version 3.5.3 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria, 2019). CSR and their 95% confidence intervals (CI) by health region during 2009 to 2017 were calculated. The CSR trend during 2009 to 2017 was calculated using the Joinpoint Regression Program Version 3.4.3 ( http://surveillance.cancer.gov/joinpoint/ ). Projections of CSRs from 2018 to 2030 as the year of measurement for Sustainable Development Goals 18 were analyzed with the following assumptions. Same annual rate change of the data from 2009 to 2017 was used until 2020, estimated time of study findings disseminated, and followed by annual rate reductions of 0.5, 1, and 2% if any interventions have been implemented in the country. MMRs, rates of PPH, NMRs, and rates of birth asphyxia per 1,000 live births and their 95% CIs were calculated and plotted by year. Correlations between CSRs and adverse maternal and perinatal outcomes among regions of Thailand were analyzed for overall correlations and stratified by years using univariate analysis. A p -value less than 0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

Results

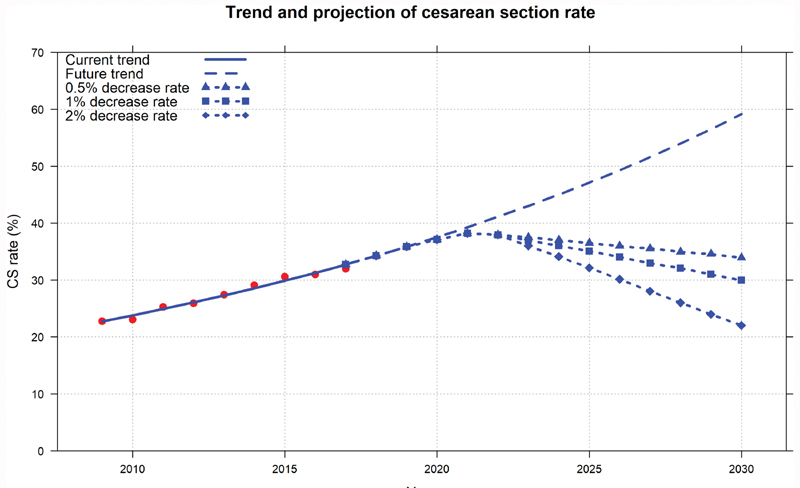

The CSRs across all regions of Thailand from 2009 to 2017 are presented in Table 1 . Annual CSR continuously increased from 23.2% in 2009 to 32.5% in 2017 ( p for trend <0.001) with a 9.3% absolute increase. The average CSR through 9 years from 2009 to 2017 for each region of Thailand were significantly increased. Figure 1 presents the projections of CSRs from 2018 to 2030 by Joinpoint regression. With the same trend of CSR between 2009 and 2017, the CSR would be 59.1% by the year 2030. When the assumption of constant decreasing annual rates of 0.5, 1, and 2% each year are considered, CSRs of 33.9, 30.0, and 22.0% were projected by the year 2030.

Table 1. Cesarean section rates classified by years and regions of Thailand.

| Cesarean section rates (%) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | p -value for trend |

| Region | ||||||||||

| 1 | 22.8 | 22.0 | 23.5 | 24.0 | 24.3 | 25.5 | 26.3 | 28.3 | 29.5 | <0.001 |

| 2 | 23.2 | 24.6 | 26.8 | 26.8 | 29.3 | 30.7 | 32.3 | 31.2 | 30.5 | <0.001 |

| 3 | 26.1 | 25.1 | 28.3 | 28.8 | 30.4 | 33.1 | 34.4 | 35.7 | 35.3 | <0.001 |

| 4 | 24.8 | 26.1 | 27.1 | 26.7 | 30.2 | 32.0 | 32.7 | 31.5 | 32.4 | <0.001 |

| 5 | 24.6 | 24.9 | 26.9 | 27.6 | 29.0 | 31.0 | 32.6 | 32.7 | 33.9 | <0.001 |

| 6 | 21.7 | 22.2 | 23.9 | 24.2 | 25.2 | 26.5 | 27.2 | 28.2 | 29.0 | <0.001 |

| 7 | 20.1 | 21.1 | 23.9 | 24.5 | 27.5 | 29.2 | 31.5 | 32.3 | 34.4 | <0.001 |

| 8 | 18.3 | 19.0 | 21.3 | 22.4 | 23.8 | 25.4 | 27.3 | 28.0 | 30.0 | <0.001 |

| 9 | 21.4 | 21.3 | 23.8 | 25.0 | 27.1 | 27.7 | 30.2 | 30.9 | 32.6 | <0.001 |

| 10 | 20.6 | 21.9 | 24.6 | 25.1 | 26.6 | 29.5 | 30.3 | 32.7 | 34.4 | <0.001 |

| 11 | 27.1 | 26.8 | 29.3 | 31.5 | 32.9 | 35.4 | 37.6 | 36.4 | 37.5 | <0.001 |

| 12 | 21.0 | 21.0 | 23.2 | 23.2 | 23.5 | 24.4 | 25.5 | 25.7 | 26.7 | <0.001 |

| 13 | 29.3 | 29.4 | 31.8 | 34.0 | 35.4 | 38.3 | 40.3 | 39.2 | 36.6 | 0.001 |

| Average | 23.2 | 23.5 | 25.7 | 26.4 | 28.1 | 29.9 | 31.4 | 31.7 | 32.5 | <0.001 |

| (95% CI) | (21.3–25.0) | (21.7–25.2) | (23.9–27.5) | (24.4–28.5) | (25.9–30.3) | (27.4–32.4) | (28.8–34.0) | (29.5–34.0) | (30.6–34.5) | |

Abbreviation: CI, confidence interval.

Fig. 1.

Projection of cesarean section rates (CSRs) from 2018 to 2030 by Joinpoint regression (CSRs 2009–2017—red dots; fitted and predicted line by regression—blue line; trend of CSR until 2030 projected using annual rates during 2009–2017—dashed line; and trend of CSR until 2030 projected using annual rates during 2009–2017 followed by decreasing annual rates after 2020 in different expected estimation: decreasing annual rate of 0.5%—triangle dashed line, decreasing annual rate of 1%—square dashed line, and decreasing annual rate of 2% – diamond dashed line).

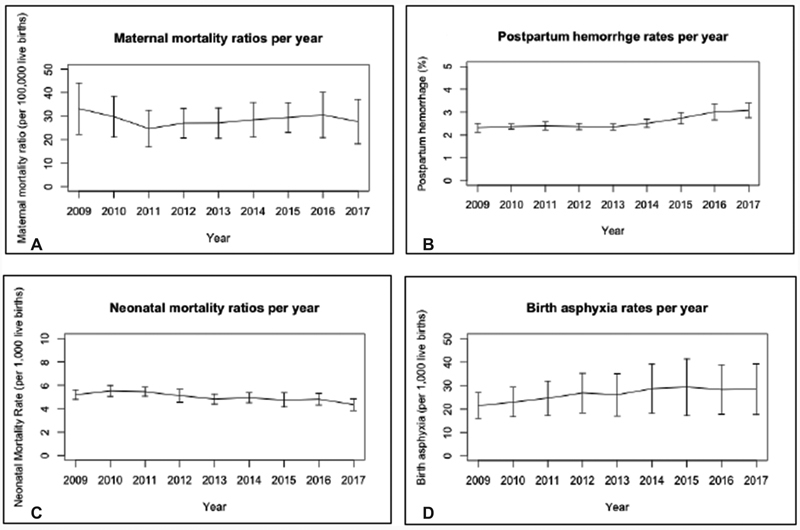

Trends of MMR, rate of PPH, NMR, and birth asphyxia rate are shown in Fig. 2 . MMRs were 33 (95% CI: 22–44) per 100,000 live births in 2009 and 28 (95% CI: 18–37) per 100,000 live births in 2017 ( p -value for trend = 0.757). Rates of PPH increased from 2.3% (95% CI: 2.1–2.5) in 2009 to 3.1% (95% CI: 2.8–3.4) in 2017 ( p -value for trend <0.001). NMRs per 1,000 live births were 5.2 (95% CI: 4.8–5.6) in 2009 and 4.4 (95% CI: 3.8–4.8) in 2009 ( p -value for trend <0.001). Rates of birth asphyxia per 1,000 live births increased from 21 (95% CI: 16–27) in 2009 to 28 (95% CI: 18–39) in 2017 ( p -value for trend = 0.083).

Fig. 2.

Trend of maternal mortality ratios, rates of postpartum hemorrhage, neonatal mortality rates per 1,000 live births, and rates of birth asphyxia per 1,000 live births from 2009 to 2017 (mean and 95% confidence interval).

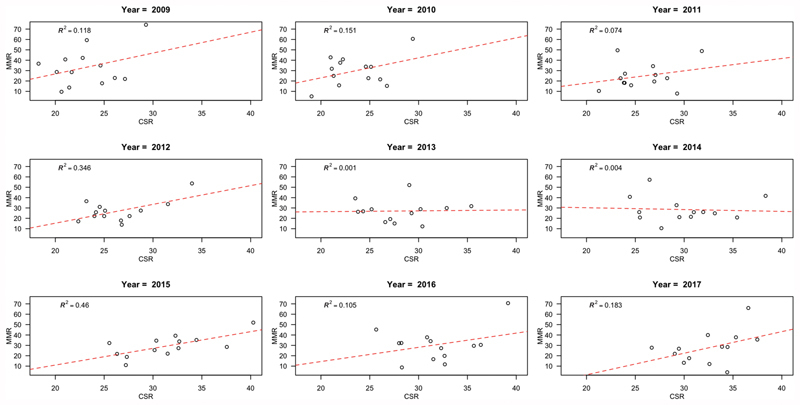

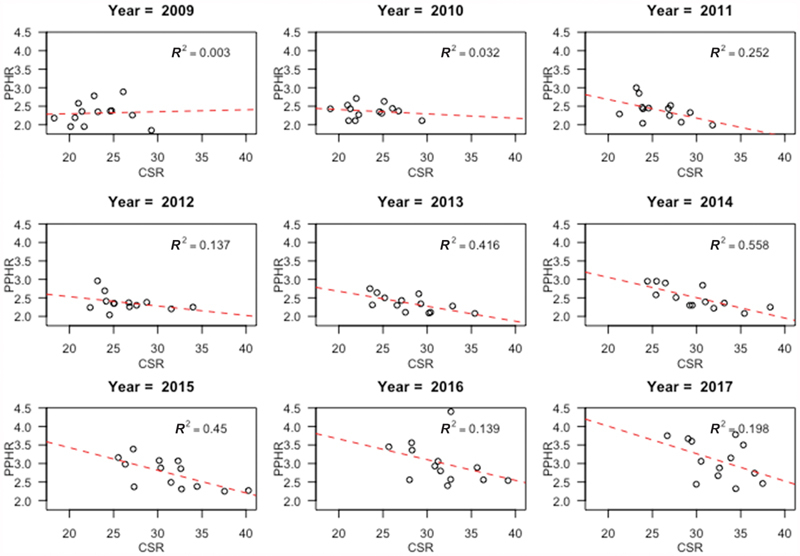

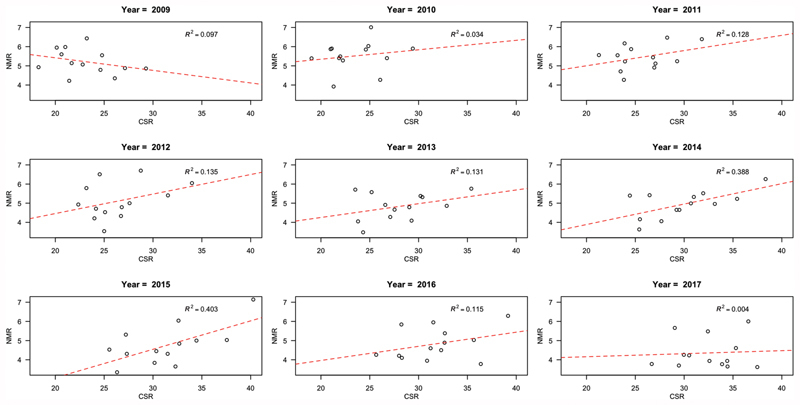

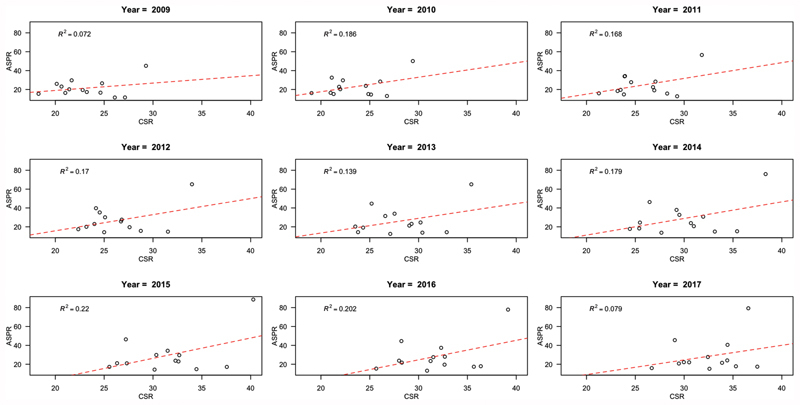

Increasing CSRs were significantly correlated with higher MMRs (correlation coefficient 0.20, p -value 0.030) and birth asphyxia rates (correlation coefficient 0.39, p -value <0.001). Positive correlation between CSRs and rates of PPH (correlation coefficient 0.14, p -value 0.138) and negative correlation between CSRs and NMRs (correlation coefficient –0.04, p -value 0.788) were found but they were not significant. Correlation of CSRs with MMRs, rates of PPH, NMRs, and birth asphyxia rates by year are shown in Figs. 3 4 5 to 6 . Same trends of correlation were found in the majority of year for MMRs and birth asphyxia rates when the analyses were stratified by year. Opposite direction of correlations between CSRs and rates of PPH or NMRs was found after stratifying by year when comparing with overall correlations.

Fig. 3.

Correlation of cesarean section rates with maternal mortality ratios by year.

Fig. 4.

Correlation of cesarean section rates with rates of postpartum hemorrhage by year.

Fig. 5.

Correlation of cesarean section rates with neonatal mortality rates by year.

Fig. 6.

Correlation of cesarean section rates with birth asphyxia rates by year.

Discussion

One-third of pregnant women in our analysis were delivered by CS. The trend of the CSR in Thailand showed a steady increase from 2009 to 2017. If this trend continues, the CSR could reach 59.1% in 2030 if no effective interventions are implemented. To maintain the CSR of 30% or to reduce the CSR to 22% in 2030, an annual reduction rate of at least 1 to 2% is needed. The MMRs decreased during the study period but rates of PPH and birth asphyxia increased. The increasing CSRs were significantly correlated with higher MMRs and birth asphyxia rates. Overall correlation between CSRs and rates of PPH was positive but not significant.

The trend of an increasing CSR found in this study is similar to a report from a public hospital in Northern Thailand 19 and the findings of CS trends in 21 countries reported in a secondary analysis of two WHO multicountry surveys, except in Japan, and the national data on CSRs from 150 countries between 1990 and 2014. 3 20 The CSRs reported in the WHO surveys (34.1% in 2004–2008 and 39.4% in 2010–2011) 3 were higher than the CSR in Thailand (23.5% in 2010 and 25.7% in 2011). However, the CSRs in our study were lower than those reported in Peru and Vietnam when CSRs in the same year were compared. 21 22 This could be explained by data collected from different settings of hospitals as the WHO surveys focused mostly at the provincial levels but data of our study included all hospital levels. The high CSR rate in Vietnam was due to the study settings including both public and private facilities, which was different from our study. The CSRs in our study were similar to the CSRs reported in the Thailand Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey 2015 to 2016. 5

The increasing trend of CSR in Thailand may be assumed by the reason that CS costs are covered by the health insurance plans 12 leading to more comfortable decision of women and doctors for delivery by CS regarding of obstetric indications. Studies on the attitudes of pregnant women during antenatal care and obstetricians & gynecologists (OB&GYN) in Thailand showed that more than 87.5% of the women and 68.9% of the OB&GYN preferred vaginal deliveries; however, one-third of the women and half of the OB&GYN agreed with women's request of CS. 23 24 A review from Latin America found that the main reasons for the high CSR were obstetric procedures such as continuous fetal heart rate monitoring or induction of labor and personal perception such as better outcomes by cesarean birth, convenience of time management, or advanced maternal age. 25 The variation in CSR across the regions of Thailand was similar to the varying rates from different regions in Turkey, Japan, and Norway. 26 27 28

Without any interventions or programs promoting reduction in CSR in Thailand, the projection of CSR by the end year of Sustainable Development Goals measurement would be ∼59.1%, almost double the current rate of 32.5%. A Cochrane review found the evidence on effective interventions including implementation of guidelines combined with mandatory second opinion, physician education by obstetricians, or audit, and feedback targeting at health-care professionals in reducing CSR. 29 A retrospective study in France found that the audit of CS situation undergone by the doctors and training of new doctors to be concerned about high CSR was associated with a reduction in CSR. 30

Slightly lower MMR was shown in our analysis that was similar to the report of 2009 to 2015 WHO estimate in Thailand. 31 We found that CSR was positively correlated with MMR that was different from the results of a secondary analysis using data from the Demographic and Health Surveys or Multiple Indicator Cluster Surveys, in which a negative association between CSR and mortality was not significant after adjusting for the countries having CSR exceeding 10%. 7 Similarly, a review of maternal mortality during 1995 to 2009 in Ireland showed constant MMR along with increasing trend of CSR from 14.1% in 1995 to 26.5% in 2009. 32

A significantly increasing rates of PPH was observed over time in our study, which was similar to the finding of studies from Australia and Canada, although our rate of increase was less than half the rates in those studies. 33 34 Overall correlation of increased CSR and PPH was not significant, but the negative correlations were shown in many years. This could be explained by noting that CSR alone was not the only factor related to rate of PPH. A retrospective cohort study at one public hospital in Bangkok, the capital and largest city of Thailand, found the main risk factors for PPH were prolonged third stage of labor, retained placenta, lacerations of the birth canal, and placenta previa. 35 In a study from Zimbabwe, Africa, even though CS was not significantly associated with PPH, two-thirds of the women giving either vaginal birth or who underwent CS were diagnosed as PPH with estimated blood losses of 500 to 1000 mL and 1000 to 1500 mL, respectively. 36 Another study found that induced labor and previous CS increased the risk of severe PPH. 37

NMR found in our study was somewhat higher than the point estimate value of more developed countries reported from a study using worldwide country-level data. 7 Although trend of NMR was slightly decreased over time, the correlations between NMRs and CSRs were mostly positive when stratified by years. This finding was similar to the findings of the 2005 WHO global survey on maternal and perinatal health in Latin America 8 and 2007 to 2008 in Asia in both antepartum and intrapartum CS with indications. 38

Birth asphyxia rates were significantly higher in our study and correlated with increasing CSRs, which was different from the findings of a secondary analysis of two WHO surveys that found that increasing rates of CS were not significantly associated with neonatal morbidity and mortality. 39 An ecological study using worldwide country-level data found that a CSR higher than 10% was not associated with substantial decreases in maternal and neonatal mortality after controlling for socio-economic factors. 7 These differences could be explained by studies using different measurements of neonatal outcomes.

We collected data from 9 years that were statistically sufficient to determine the CSR trend over that time period. Maternal death, PPH, and birth asphyxia rates analyzed in our study are important maternal and perinatal health measures reported at international level and in Thailand. 6 7 8 40

There were some limitations of this study. First, the analysis was based on aggregate data without any demographic or clinical characteristics at individual level. Importantly, the correlations between CSR and maternal and perinatal outcomes were adjusted only by year. We therefore could not control for other potential confounding factors. A report of Ministry of Public Health, Thailand, presented that the CSR in 2007 was double in women under CSMBS compared with women under UCS. Second, the CSR projections were determined by estimating future CSR from retrospective CSR without other determinants using Joinpoint analysis. Third, the number of live births in this analysis was approximately two-thirds of all live births recorded in the national birth registration. Finally, the analysis by correlation or regression aimed to present the association of CSR with MMR, rate of PPH, NMR and birth asphyxia rate, not predicting their trends.

CSRs continuously increased during the study period in Thailand that were correlated with adverse maternal and perinatal outcomes. The increasing CS trend without any interventions aiming to reduce the CSR is alarming and requires interventions to achieve appropriate CSR. Available individual data at nation-wide scale are essential to be collected and studied along with the country strategies for reduction of rising CSRs.

Acknowledgments

We thank the National Health Security Office of Thailand on providing the aggregate data without revealing the identities of the patients for data analysis.

Conflict of Interest None declared.

Disclosure of Any Source of Financial Support or Funding

All authors declare no conflict of interest. No funding sources were involved in this secondary analysis.

Contributions to Authorship

All authors participated in the concept of the study. TL obtained the necessary permissions for data utilization, and participated in data analysis and interpretation, and drafting the manuscript. JS participated in data analysis and interpretation. JT participated in data extraction and management. PL helped with data interpretation. All authors reviewed the draft of the manuscript and approved the final manuscript for submission.

Details of Ethical Approval

A study protocol of secondary analysis was approved by the Institute Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Medicine, Prince of Songkla University with the reference number of REC 60–439–18–1 (Exempt determination), date of approval on 27 November 2017.

References

- 1.Gregory K D, Jackson S, Korst L, Fridman M. Cesarean versus vaginal delivery: whose risks? whose benefits? Am J Perinatol. 2012;29(01):7–18. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1285829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization.WHO statement on caesarean section rates Geneva: World Health Organization; 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vogel J P, Betrán A P, Vindevoghel N et al. Use of the Robson classification to assess caesarean section trends in 21 countries: a secondary analysis of two WHO multicountry surveys. Lancet Glob Health. 2015;3(05):e260–e270. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(15)70094-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Health Organization.World Health Statistics 2010 Geneva: World Health Organization; 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 5.National Statistical Office and United Nations Children's Fund.Thailand multiple indicator cluster survey 2015–2016, final report Bangkok: National Statistical Office and United Nations Children's Fund; 2016 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Souza J P, Gülmezoglu A, Lumbiganon P et al. Caesarean section without medical indications is associated with an increased risk of adverse short-term maternal outcomes: the 2004–2008 WHO global survey on maternal and perinatal health. BMC Med. 2010;8:71. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-8-71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ye J, Zhang J, Mikolajczyk R, Torloni M R, Gülmezoglu A M, Betran A P. Association between rates of caesarean section and maternal and neonatal mortality in the 21st century: a worldwide population-based ecological study with longitudinal data. BJOG. 2016;123(05):745–753. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.13592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Villar J, Valladares E, Wojdyla Det al. Caesarean delivery rates and pregnancy outcomes: the 2005 WHO global survey on maternal and perinatal health in Latin America Lancet 2006367(9525):1819–1829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cristina Rossi A, Mullin P. The etiology of maternal mortality in developed countries: a systematic review of literature. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2012;285(06):1499–1503. doi: 10.1007/s00404-012-2301-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kupari M, Talola N, Luukkaala T, Tihtonen K. Does an increased cesarean section rate improve neonatal outcome in term pregnancies? Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2016;294(01):41–46. doi: 10.1007/s00404-015-3942-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sakunphanit T. Bangkok: International Labour Organization; 2008. Universal health care coverage through pluralistic approaches: experience from Thailand. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tangcharoensathien V, Witthayapipopsakul W, Panichkriangkrai W, Patcharanarumol W, Mills A.Health systems development in Thailand: a solid platform for successful implementation of universal health coverage Lancet 2018391(10126):1205–1223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Paek S C, Meemon N, Wan T TH. Thailand's Universal Coverage Scheme and its impact on health-seeking behavior. Springerplus. 2016;5(01):1952. doi: 10.1186/s40064-016-3665-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kongsri S, Limwattananon S, Sirilak S, Prakongsai P, Tangcharoensathien V. Equity of access to and utilization of reproductive health services in Thailand: national Reproductive Health Survey data, 2006 and 2009. Reprod Health Matters. 2011;19(37):86–97. doi: 10.1016/S0968-8080(11)37569-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Patcharanarumol W, Panichkriangkrai W, Sommanuttaweechai A, Hanson K, Wanwong Y, Tangcharoensathien V. Strategic purchasing and health system efficiency: a comparison of two financing schemes in Thailand. PLoS One. 2018;13(04):e0195179. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0195179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim M K, Lee S M, Bae S-H et al. Socioeconomic status can affect pregnancy outcomes and complications, even with a universal healthcare system. Int J Equity Health. 2018;17(01):2. doi: 10.1186/s12939-017-0715-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Teerawattananon Y, Tangcharoensathien V. Designing a reproductive health services package in the universal health insurance scheme in Thailand: match and mismatch of need, demand and supply. Health Policy Plan. 2004;19 01:i31–i39. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czh043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rosa W, Ed.Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development New York, NY: Springer Publishing Company; 2017[cited 2018 Nov 30]. Available from:http://connect.springerpub.com/lookup/doi/10.1891/9780826190123.ap02 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Charoenboon C, Srisupundit K, Tongsong T. Rise in cesarean section rate over a 20-year period in a public sector hospital in northern Thailand. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2013;287(01):47–52. doi: 10.1007/s00404-012-2531-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Betrán A P, Ye J, Moller A-B, Zhang J, Gülmezoglu A M, Torloni M R. The increasing trend in caesarean section rates: global, regional and national estimates: 1990-2014. PLoS One. 2016;11(02):e0148343. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0148343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Giang H TN, Ulrich S, Tran H T, Bechtold-Dalla Pozza S. Monitoring and interventions are needed to reduce the very high caesarean section rates in Vietnam. Acta Paediatr. 2018;107(12):2109–2114. doi: 10.1111/apa.14376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tapia V, Betran A P, Gonzales G F. Caesarean section in Peru: analysis of trends using the Robson classification system. PLOS ONE. 2016;11(02):e0148138. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0148138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yamasmit W, Chaithongwongwatthana S. Attitude and preference of Thai pregnant women towards mode of delivery. J Med Assoc Thai. 2012;95(05):619–624. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kovavisarach E, Ruttanapan K. Self-preferred route of delivery of Thai obstetricians and gynecologists. J Med Assoc Thai. 2016;99 02:S84–S90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mariani G L, Vain N E. The rising incidence and impact of non-medically indicated pre-labour cesarean section in Latin America. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med. 2019;24(01):11–17. doi: 10.1016/j.siny.2018.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Santas G, Santas F. Trends of caesarean section rates in Turkey. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2018;38(05):658–662. doi: 10.1080/01443615.2017.1400525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Norum J, Svee T E. Caesarean section rates and activity-based funding in Northern Norway: a model-based study using the World Health Organization's recommendation. Obstet Gynecol Int. 2018;2018:6.764258E6. doi: 10.1155/2018/6764258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Maeda E, Ishihara O, Tomio J et al. Cesarean section rates and local resources for perinatal care in Japan: a nationwide ecological study using the national database of health insurance claims. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2018;44(02):208–216. doi: 10.1111/jog.13518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chen I, Opiyo N, Tavender Eet al. Non-clinical interventions for reducing unnecessary caesarean section. Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care Group, editor. Cochrane Database Syst Rev [Internet] 2018[cited 2018 Oct 10]; Available from:http://doi.wiley.com/10.1002/14651858.CD005528.pub3

- 30.Lesieur E, Blanc J, Loundou A et al. Teaching and performing audits on caesarean delivery reduce the caesarean delivery rate. PLoS One. 2018;13(08):e0202475. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0202475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.World Health Organization, UNICEF, UNFPA, World Bank Group and the United Nations Population DivisionTrends in maternal mortality: 1990 to 2015: estimates by WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA, World Bank Group and the United Nations Population Division [Internet] 2015[cited 2018 Oct 16]. Available from:http://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/monitoring/maternal-mortality-2015/en/

- 32.O'Dwyer V, Hogan J L, Farah N, Kennelly M M, Fitzpatrick C, Turner M J. Maternal mortality and the rising cesarean rate. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2012;116(02):162–164. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2011.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ford J B, Roberts C L, Simpson J M, Vaughan J, Cameron C A. Increased postpartum hemorrhage rates in Australia. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2007;98(03):237–243. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2007.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mehrabadi A, Liu S, Bartholomew S et al. Temporal trends in postpartum hemorrhage and severe postpartum hemorrhage in Canada from 2003 to 2010. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2014;36(01):21–33. doi: 10.1016/S1701-2163(15)30680-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rueangchainikhom W, Srisuwan S, Prommas S, Sarapak S. Risk factors for primary postpartum hemorrhage in Bhumibol Adulyadej Hospital. J Med Assoc Thai. 2009;92(12):1586–1590. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ngwenya S. Postpartum hemorrhage: incidence, risk factors, and outcomes in a low-resource setting. Int J Womens Health. 2016;8:647–650. doi: 10.2147/IJWH.S119232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Al-Zirqi I, Vangen S, Forsén L, Stray-Pedersen B. Effects of onset of labor and mode of delivery on severe postpartum hemorrhage. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;201(03):2730–2.73E11. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2009.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lumbiganon P, Laopaiboon M, Gülmezoglu A Met al. Method of delivery and pregnancy outcomes in Asia: the WHO global survey on maternal and perinatal health 2007-08 Lancet 2010375(9713):490–499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhao Y, Zhang J, Zamora J et al. Increases in caesarean delivery rates and change of perinatal outcomes in low- and middle-income countries: a hospital-level analysis of two WHO surveys. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2017;31(04):251–262. doi: 10.1111/ppe.12363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chumpathong S, Sirithanetbhol S, Salakij B, Visalyaputra S, Parakkamodom S, Wataganara T. Maternal and neonatal outcomes in women with severe pre-eclampsia undergoing cesarean section: a 10-year retrospective study from a single tertiary care center: anesthetic point of view. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2016;29(24):4096–4100. doi: 10.3109/14767058.2016.1159674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]