Abstract

OBJECTIVE:

Our aim was to study the potential effect of neighbourhood deprivation on incident heart failure (HF) in patients with diabetes mellitus (DM).

METHODS:

The study population included adults (n=434,542) aged 30 years or older with DM followed from 2005 to 2015 in Sweden for incident HF. The association between neighbourhood deprivation and the outcome was explored using Cox regression analysis, with hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs). All models were conducted in both men and women and adjusted for age, educational level, family income, employment status, region of residence, immigrant status, marital status, mobility, and co-morbidities. DM patients living in neighbourhoods with high or moderate levels of deprivation were compared with those living in neighbourhoods with low deprivation scores (reference group).

RESULTS:

There was an association between level of neighbourhood deprivation and HF in DM patients. The HRs were 1.27, 95% CI 1.21–1.33, for men and 1.30, 95% CI 1.23–1.37, for women) among DM patients living in high deprivation neighbourhoods compared to those from low deprivation neighbourhoods. After adjustments for potential confounders, the higher HRs of HF remained significant: 1.11, 95% CI 1.06–1.16, in men and 1.15, 95% CI 1.09–1.21, in women living in high deprivation neighbourhoods.

CONCLUSIONS:

Increased incidence rates of HF among DM patients living in deprived neighbourhoods raise important clinical and public health concerns. These findings could serve as an aid to policy-makers when allocating resources in primary health care settings as well as to clinicians who encounter patients in deprived neighbourhoods.

Keywords: Heart failure, diabetes mellitus, neighbourhood, Sweden

INTRODUCTION

In recent years, the awareness in the scientific community has steadily increased concerning the two-way association between diabetes mellitus (DM) and heart failure (HF) and has also gained more research interest1,2. DM is an independent risk factor for HF, with a 5-fold increased risk of HF in women with DM and a 2.4-fold increased risk in men1. In a recent Swedish population-based study, the hazard ratio for HF was 1.45 in patients with DM compared to controls2.

In general, the incidence of HF varies by individual socioeconomic status (SES); higher income has previously been associated with a lower risk of developing HF3,4. Moreover, risk factors for HF, such as hypertension and coronary heart disease (CHD), also vary with SES5. In addition to individual-level socioeconomic factors, there are also neighbourhood-level socioeconomic factors that could increase the risk of DM. Previous studies have shown that the prevalence of type 2 DM is higher in highly deprived than in less deprived or affluent neighbourhoods6–9. Furthermore, it is known that SES is associated with HF. However, the association between neighbourhood deprivation and HF in patients with DM remains to be established. If established, such an association would help identify DM patients deemed to be at an increased risk of HF. Therefore, we sought to assess the association between neighbourhood deprivation and incident HF in patients diagnosed with or medically treated for DM in a nationwide follow-up study.

Our first aim was to investigate whether there is a difference in the risk of incident HF between patients with DM living in deprived neighbourhoods and patients with DM living in less deprived/affluent neighbourhoods. The second aim was to investigate whether this possible difference remains after accounting for individual-level sociodemographic characteristics (age, marital status, family income, education, employment status, immigration status, region of residence, mobility and co-morbidities).

METHODS

Data used in this study were retrieved from nationwide, comprehensive registers that contains individual-level information on all people in Sweden, including age, sex, socioeconomic status, geographical region of residence, hospital diagnoses and dates of hospital admissions (1964–2015), date of emigration, and date and cause of death. The unique datasets for this study were constructed using several national Swedish data registers including the Total Population Register, the Swedish Hospital Register (i.e., In-Patient Register), and Prescription Register (available between 2005–2015). Diagnoses were reported according to the International Classification of Diseases (ICD). All linkages were performed using the national 10-digit civic registration number, which is assigned to each person in Sweden upon birth or immigration to the country. This number was replaced by serial numbers to ensure the integrity of all individuals.

The nationwide prescription register was used to identify all individuals aged 30 years and older with medically treated DM. This register includes all medical prescriptions that were retrieved at any pharmacy in Sweden between July 1, 2005 and December 31, 2015. All individuals that were prescribed insulin or oral antidiabetic agents or picked up a prescription for insulin or oral antidiabetic agents during the entire time period between July 1, 2005 and December 31, 2015 were included in the study population. The ATC-codes A10 were used to identify the patients from the prescription register. In addition, we used the main diagnoses for DM recorded in the In-Patient Register. In the present study, the first-time hospital admission for DM was defined as an incident event according to ICD-10 E10-E14 during the study period. We identified unique 466,322 DM patients during the study period and excluded 11875 (2.6%) individuals who had previously been diagnosed with HF (1997–2004) and 9125 individuals (2.0%) who were diagnosed with HF before the first diagnosis of DM during the study period. To remove possible coding errors, we also excluded 10790 (2.3%) individuals who had a reported emigration date before the HF diagnosis. A total of 434,542 DM patients (93.2% of the original cohort) remained suitable for inclusion in the study.

Outcome variables: The Swedish Hospital Discharge/In-Patient register was used to identify the outcome variable of HF, ICD-10 I50, incident HF. Incident HF was defined as the first hospitalization for HF during the study period, after excluding individuals with preexisting disease.

Explanatory variables

All individual-level variables were assessed on 12/31/2005. Separate analyses were conducted for women and men. Age was used as a continuous variable from age ≥ 30 years. Marital status was divided into two groups: (1) married/cohabitating, and (2) never married, widowed, or divorced. Educational attainment was divided into three groups based on: completion of compulsory school or less (< 9 years), practical high school or some theoretical high school (10–12 years), or theoretical high school and/or college (>12 years). Immigration status was divided into two groups: (1) born in Sweden and (2) born outside Sweden. Mobility (moved) was based on the length of time lived in the neighbourhood, categorised as < 5 years or ≥ 5 years. Region of residence was divided into three groups: large cities (Stockholm, Gothenburg, and Malmö), middle-sized towns, and small towns/rural areas. Employment status was divided into two groups: employed or unemployed. Comorbidities were identified from the Swedish inpatient and outpatient registers as follows: hypertension (I10–I15); CHD (I20–I25); obesity (E65–E68); chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) (J40–J47); alcoholism and related liver disorders (F10 and K70); depression (F32); and stroke (I60–I69). Family income was based on the annual family income divided by the number of people in the family, i.e. individual family income per capita. This variable was provided by Statistics Sweden (the Swedish Government-owned statistics bureau). The income parameter also took into consideration the ages of people in the family and used a weighted system whereby small children were given lower weights than adolescents and adults. The calculation procedure was performed as follows: The sum of all family members’ incomes was multiplied by the individual’s consumption weight divided by the family members’ total consumption weight.

Neighbourhood-level variable

The home addresses of all Swedish adults have been geocoded to small geographic administrative units that have boundaries defined by homogeneous types of buildings. These neighbourhood units, which are called small area market statistics or SAMS, have an average of 1,000–2,000 people and were used as proxies for neighbourhoods, as has been done in previous research10.

Neighbourhood Deprivation Index:

A summary measure was used to characterize neighbourhood-level deprivation. We identified deprivation indicators used by past studies to characterize neighbourhood environments and then used a principal components analysis to select deprivation indicators in the Swedish national database11. The following four variables were selected for those aged 25–64: low educational status (<10 years of formal education); low income (income from all sources, including that from interest and dividends, defined as less than 50% of individual median income);12 unemployment (not employed, excluding full-time students, those completing compulsory military service, and early retirees); and social welfare assistance. The neighborhood deprivation index was calculated based on the population aged 25–64 years because this age group (i.e., the working population) was considered to be more socioeconomically active than other age groups. The study population, however, consisted of individuals aged 30 years and older. Each of the four deprivation variables loaded on the first principal component with similar loadings (+.47 to +.53) and explained 52% of the variation between these variables.

A z score was calculated for each SAMS neighbourhood. The z scores, weighted by the coefficients for the eigenvectors, were then summed to create the index.13 The index was categorized into three groups: below one standard deviation (SD) from the mean (low deprivation), above one SD from the mean (high deprivation), and within one SD of the mean (moderate deprivation). Higher scores reflect more deprived neighbourhoods. Using this categorization, 1383 neighbourhoods were categorized as low deprivation (13.3% of the study population), 4791 as moderate (67.4% of the study population), and 1093 as high deprivation neighbourhoods (19.3% of the study population) (Supplementary Table S1).

Statistical Analysis

Person-years were calculated from the start of follow-up until first hospitalization for HF, death, emigration or the end of the study on December 31, 2015. The associations between the individual variables and HF were analysed with Cox regression models. Cox proportional hazard models are used to study the association between certain variables and the time it takes for a specified event to happen, in this case the first/incident event of HF. The stratified Cox proportional hazards model provides a Hazard ratio (HR) for HF that is adjusted for the individual variables. First, a univariate Cox regression was performed for each variable. Next, a multivariate Cox regression model including all variables was calculated. Interaction tests were performed in order to examine whether the association between neighbourhood deprivation and HF among DM patients was affected by any of the individual variables. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS 9.3.

Ethical Considerations

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee at Lund University.

RESULTS

Table 1 shows the study population comprising a total of 434,542 DM patients, number of HF incident events and incidence of HF in the DM patients by neighbourhood-level deprivation. During the follow-up (mean follow-up = 6 years), there were 26,511 and 20,772 HF incident events among the men and women with DM, respectively. There was an apparent gradient for the incidence rate; the HF incidence became higher by increasing neighbourhood-level deprivation. The same pattern appeared in most subgroups.

Table 1.

Distribution of population, number of incident HF, cumulative rates (%) of incident heart failure (HF) in diabetes patients, 2005–2015, Sweden.

| Population | Incident HF | Rate (%) of HF by neighbourhood deprivation | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % | No. | % | Low | Moderate | High | P-value | |

| 57890 | 292812 | 83840 | ||||||

| Total population | 434542 | (13.3%) | (67.4%) | (19.3%) | ||||

| 5357 | 32423 | 9503 | ||||||

| Total incident HF | 47283 | (11.3%) | (68.6%) | (20.1%) | ||||

| Gender | 0.9810 | |||||||

| Males | 239567 | 55.1 | 26511 | 56.1 | 9.7 | 11.3 | 11.3 | |

| Females | 194975 | 44.9 | 20772 | 43.9 | 8.6 | 10.8 | 11.3 | |

| Age (years) | <0.001 | |||||||

| 30–39 | 24192 | 5.6 | 235 | 0.5 | 0.7 | 0.9 | 1.2 | |

| 40–49 | 49390 | 11.4 | 1192 | 2.5 | 2.0 | 2.4 | 2.8 | |

| 50–59 | 95456 | 22.0 | 4476 | 9.5 | 3.6 | 4.7 | 5.5 | |

| 60–69 | 119581 | 27.5 | 11397 | 24.1 | 7.9 | 9.4 | 11.3 | |

| 70–79 | 93204 | 21.4 | 17435 | 36.9 | 16.9 | 18.7 | 19.9 | |

| ≥ 80 | 52719 | 12.1 | 12548 | 26.5 | 22.9 | 23.9 | 24.0 | |

| Education attainment | <0.001 | |||||||

| ≤ 9 years | 188398 | 43.4 | 27110 | 57.3 | 13.4 | 14.6 | 14.2 | |

| 10–12 years | 131177 | 30.2 | 11366 | 24.0 | 8.2 | 8.6 | 9.1 | |

| ≥ 12 years | 114967 | 26.5 | 8807 | 18.6 | 6.6 | 7.7 | 8.6 | |

| Family income | <0.001 | |||||||

| Middle-high income | 108017 | 24.9 | 11974 | 25.3 | 10.5 | 11.5 | 10.0 | |

| Middle-low income | 109096 | 25.1 | 15075 | 31.9 | 11.4 | 14.1 | 14.1 | |

| Low income | 109064 | 25.1 | 12090 | 25.6 | 10.0 | 11.2 | 11.5 | |

| High income | 108365 | 24.9 | 8144 | 17.2 | 6.9 | 7.6 | 8.2 | |

| Region of residence | <0.001 | |||||||

| Large cities | 111226 | 25.6 | 11393 | 24.1 | 9.1 | 10.5 | 10.3 | |

| Southern Sweden | 229331 | 52.8 | 25573 | 54.1 | 9.4 | 11.3 | 12.0 | |

| Northern Sweden | 93985 | 21.6 | 10317 | 21.8 | 9.1 | 11.1 | 12.0 | |

| Marital status | <0.001 | |||||||

| Married/cohabiting | 231230 | 53.2 | 23050 | 48.7 | 8.5 | 10.2 | 10.5 | |

| Not married | 203312 | 46.8 | 24233 | 51.3 | 10.6 | 12.1 | 12.1 | |

| Mobility | <0.001 | |||||||

| Notmoved | 306420 | 70.5 | 29426 | 62.2 | 8.0 | 9.7 | 10.4 | |

| Moved | 128122 | 29.5 | 17857 | 37.8 | 12.6 | 14.4 | 13.2 | |

| Employment status | <0.001 | |||||||

| Yes | 161007 | 37.1 | 6163 | 13.0 | 8.7 | 10.6 | 5.6 | |

| No | 273535 | 62.9 | 41120 | 87.0 | 10.6 | 12.3 | 10.6 | |

| Hospitalisation of COPD | 0.0326 | |||||||

| No | 399091 | 91.8 | 38971 | 82.4 | 8.3 | 10.0 | 10.0 | |

| Yes | 35451 | 8.2 | 8312 | 17.6 | 21.7 | 23.4 | 24.4 | |

| Hospitalisation of alcoholism and related liver disorders | <0.001 | |||||||

| No | 420106 | 96.7 | 46018 | 97.3 | 9.2 | 11.2 | 11.5 | |

| Yes | 14436 | 3.3 | 1265 | 2.7 | 10.9 | 8.5 | 8.5 | |

| Hospitalisation of CHD | <0.001 | |||||||

| No | 328138 | 75.5 | 20162 | 42.6 | 5.0 | 6.3 | 6.4 | |

| Yes | 106404 | 24.5 | 27121 | 57.4 | 23.6 | 25.6 | 26.4 | |

| Hospitalisation of obesity | <0.001 | |||||||

| No | 410897 | 94.6 | 44570 | 94.3 | 9.2 | 11.1 | 11.3 | |

| Yes | 23645 | 5.4 | 2713 | 5.7 | 10.8 | 11.4 | 12.0 | |

| Hospitalisation of hypertension | <0.001 | |||||||

| No | 259162 | 59.6 | 20370 | 43.1 | 6.3 | 8.1 | 8.0 | |

| Yes | 175380 | 40.4 | 26913 | 56.9 | 13.3 | 15.4 | 16.5 | |

| Hospitalisation of depression | 0.1680 | |||||||

| No | 419437 | 96.5 | 45822 | 96.9 | 9.2 | 11.1 | 11.5 | |

| Yes | 15105 | 3.5 | 1461 | 3.1 | 9.5 | 10.1 | 8.8 | |

| Hospitalisation of stroke | 0.0528 | |||||||

| No | 380176 | 87.5 | 37465 | 79.2 | 8.2 | 10.1 | 10.3 | |

| Yes | 54366 | 12.5 | 9818 | 20.8 | 17.3 | 18.1 | 18.5 | |

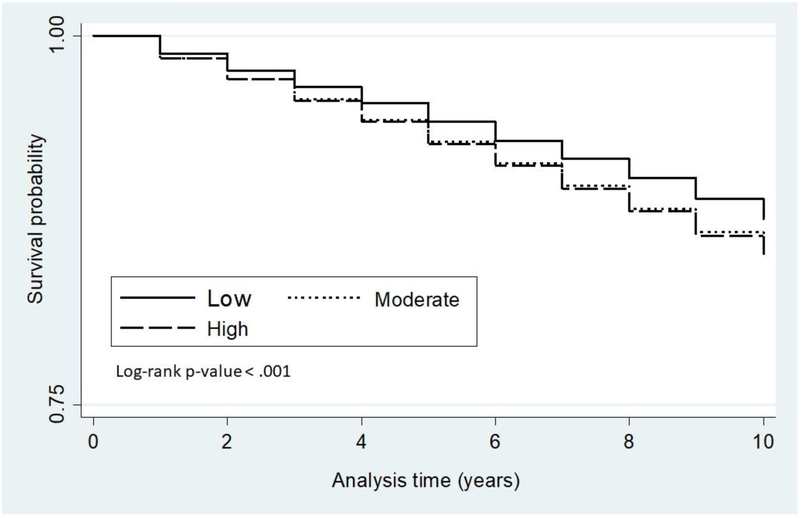

The proportion of patients affected with HF increased among individuals living in high-deprivation neighbourhoods. Figure 1 shows the Kaplan–Meir curves for the duration of survival until the first incident HF by different levels of neighbourhood deprivation. A graded effect appeared with a poorer prognosis for those with a high level of neighbourhood deprivation.

Figure 1.

The Kaplan–Meier curves for the duration of survival until first diagnosis of/incident HF in DM patients by different levels of neighbourhood deprivation.

Table 2 shows the Hazard ratios (HRs) for HF in men. The results indicate the presence of a gradient where HF incidence became greater with increasing neighbourhood deprivation. For men, the HRs were 1.14 (95% CI = 1.10–1.19) and 1.27 (95% CI = 1.21–1.33) in moderate and high deprivation neighbourhoods, respectively. The results of the full model show that the HRs decreased, after adjustment for the individual-level variables; the HRs in the full model remained, however, significant in both moderate-deprivation neighbourhoods (HR = 1.08, 95% CI = 1.04–1.12) and high-deprivation neighbourhoods (HR = 1.11, 95% CI = 1.06–1.16).

Table 2.

Hazard ratios (HR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) for incident HF in men; Results of Cox regression models

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI | HR | 95% CI | HR | 95% CI | ||||

| Neighbourhood deprivation (ref. Low) | |||||||||

| Moderate | 1.14 | 1.10 | 1.19 | 1.08 | 1.04 | 1.12 | 1.08 | 1.04 | 1.12 |

| High | 1.27 | 1.21 | 1.33 | 1.12 | 1.07 | 1.17 | 1.11 | 1.06 | 1.16 |

| Age | 1.07 | 1.07 | 1.08 | 1.06 | 1.06 | 1.06 | 1.06 | 1.06 | 1.06 |

| Family income (ref. Highest quartiles) | |||||||||

| Middle-high income | 1.31 | 1.26 | 1.36 | 1.11 | 1.07 | 1.16 | 1.16 | 1.11 | 1.21 |

| Middle-low income | 1.34 | 1.29 | 1.38 | 1.09 | 1.05 | 1.13 | 1.11 | 1.07 | 1.15 |

| Low income | 1.26 | 1.22 | 1.30 | 1.10 | 1.06 | 1.14 | 1.09 | 1.05 | 1.13 |

| Education attainment (ref. ≥ 12 years) | |||||||||

| ≤ 9 years | 1.25 | 1.21 | 1.29 | 1.19 | 1.15 | 1.23 | 1.14 | 1.11 | 1.18 |

| 10–11 years | 1.20 | 1.16 | 1.25 | 1.15 | 1.11 | 1.19 | 1.10 | 1.07 | 1.14 |

| Country of origin (ref. Sweden) | 1.10 | 1.06 | 1.14 | 1.02 | 0.98 | 1.06 | 0.98 | 0.94 | 1.02 |

| Marital status (ref. Married/cohabiting) | 1.20 | 1.17 | 1.23 | 1.12 | 1.09 | 1.14 | 1.17 | 1.14 | 1.20 |

| Region of residence (ref. Large cities) | |||||||||

| Southern Sweden | 0.95 | 0.92 | 0.98 | 0.96 | 0.93 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.96 | 1.02 |

| Northern Sweden | 0.94 | 0.90 | 0.97 | 0.94 | 0.90 | 0.97 | 0.95 | 0.91 | 0.98 |

| Mobility (ref. Not moved) | 1.64 | 1.60 | 1.68 | 1.60 | 1.56 | 1.65 | 1.63 | 1.59 | 1.67 |

| Employment status (ref. Yes) | 1.59 | 1.53 | 1.65 | 1.48 | 1.43 | 1.54 | 1.26 | 1.21 | 1.31 |

| Hospitalization of COPD (ref. Non) | 2.45 | 2.37 | 2.53 | 2.02 | 1.96 | 2.09 | |||

| Hospitalization of alcoholism and related liver disorders (ref. Non) | 1.41 | 1.33 | 1.50 | 1.20 | 1.13 | 1.28 | |||

| Hospitalization of obesity (ref. Non) | 2.50 | 2.37 | 2.64 | 1.95 | 1.85 | 2.06 | |||

| Hospitalization of depression (ref. Non) | 1.27 | 1.19 | 1.37 | 1.01 | 0.94 | 1.08 | |||

| Hospitalization of hypertension (ref. Non) | 1.68 | 1.64 | 1.72 | 1.39 | 1.35 | 1.42 | |||

| Hospitalization of CHD (ref. Non) | 3.36 | 3.27 | 3.44 | 3.06 | 2.98 | 3.14 | |||

| Hospitalization of stroke (ref. Non) | 1.25 | 1.21 | 1.29 | 1.09 | 1.05 | 1.12 | |||

HR: Hazard ratio; CI: Confidence interval; HF: Heart Failure; COPD: Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CHD: Coronary heart disease.

Model 1: Univariate model, adjusted for age; Model 2. Adjusted for individual characteristics; Model 3. Full model.

Table 3 shows the HRs for HF in women; the corresponding figures of HF for women were 1.16 (95% CI = 1.10–1.21) and 1.30 (95% CI = 1.23–1.37). The results of the full model show that the HRs decreased, after adjustment for the individual-level variables; the HRs in the full model remained, however, significant in both moderate-deprivation neighbourhoods (HR = 1.10, 95% CI = 1.05–1.16) and high-deprivation neighbourhoods (HR = 1.15, 95% CI = 1.09–1.21).

Table 3.

Hazard ratios (HR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) for incident HF in women; Results of Cox regression models

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI | HR | 95% CI | HR | 95% CI | ||||

| Neighbourhood deprivation (ref. Low) | |||||||||

| Moderate | 1.16 | 1.10 | 1.21 | 1.11 | 1.06 | 1.16 | 1.10 | 1.05 | 1.16 |

| High | 1.30 | 1.23 | 1.37 | 1.17 | 1.11 | 1.24 | 1.15 | 1.09 | 1.21 |

| Age | 1.08 | 1.07 | 1.08 | 1.06 | 1.06 | 1.06 | 1.06 | 1.06 | 1.06 |

| Family income (ref. Highest quartiles) | |||||||||

| Middle-high income | 1.23 | 1.16 | 1.30 | 1.08 | 1.01 | 1.14 | 1.10 | 1.03 | 1.17 |

| Middle-low income | 1.34 | 1.27 | 1.42 | 1.13 | 1.06 | 1.20 | 1.10 | 1.04 | 1.17 |

| Low income | 1.18 | 1.11 | 1.25 | 1.08 | 1.01 | 1.15 | 1.05 | 0.98 | 1.12 |

| Education attainment (ref. ≥ 12 years) | |||||||||

| ≤ 9 years | 1.25 | 1.20 | 1.30 | 1.19 | 1.14 | 1.25 | 1.12 | 1.07 | 1.17 |

| 10–11 years | 1.11 | 1.06 | 1.17 | 1.10 | 1.05 | 1.15 | 1.01 | 0.96 | 1.06 |

| Country of origin (ref. Sweden) | 1.16 | 1.12 | 1.21 | 1.10 | 1.05 | 1.15 | 1.04 | 1.00 | 1.09 |

| Marital status (ref. Married/cohabiting) | 1.19 | 1.15 | 1.22 | 1.13 | 1.10 | 1.17 | 1.14 | 1.11 | 1.18 |

| Region of residence (ref. Large cities) | |||||||||

| Southern Sweden | 0.98 | 0.95 | 1.01 | 1.00 | 0.97 | 1.04 | 1.03 | 0.99 | 1.07 |

| Northern Sweden | 0.96 | 0.92 | 1.00 | 0.99 | 0.95 | 1.03 | 0.99 | 0.95 | 1.03 |

| Mobility (ref. Not moved) | 1.63 | 1.58 | 1.68 | 1.63 | 1.58 | 1.68 | 1.64 | 1.59 | 1.69 |

| Employment (ref. Yes) | 1.93 | 1.82 | 2.05 | 1.86 | 1.75 | 1.98 | 1.51 | 1.42 | 1.60 |

| Hospitalization of COPD (ref. Non) | 2.63 | 2.54 | 2.72 | 2.17 | 2.10 | 2.25 | |||

| Hospitalization of alcoholism and related liver disorders (ref. Non) | 1.39 | 1.22 | 1.59 | 1.11 | 0.97 | 1.27 | |||

| Hospitalization of obesity (ref. Non) | 2.14 | 2.01 | 2.27 | 1.74 | 1.64 | 1.85 | |||

| Hospitalization of depression (ref. Non) | 1.28 | 1.19 | 1.38 | 1.05 | 0.98 | 1.14 | |||

| Hospitalization of hypertension (ref. Non) | 1.65 | 1.60 | 1.69 | 1.37 | 1.34 | 1.41 | |||

| Hospitalization of CHD (ref. Non) | 3.18 | 3.09 | 3.27 | 2.79 | 2.71 | 2.87 | |||

| Hospitalization of stroke (ref. Non) | 1.36 | 1.32 | 1.41 | 1.19 | 1.15 | 1.23 | |||

HR: Hazard ratio; CI: Confidence interval; HF: Heart Failure; COPD: Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CHD: Coronary heart disease.

Model 1: Univariate model, adjusted for age; Model 2. Adjusted for individual characteristics; Model 3. Full model.

There was a clear and consistent positive association between neighbourhood deprivation and HF in all socioeconomic groups, i.e., any moderation by individual SES ought to be minor and the potential interactions do not seem to be clinically meaningful.

Some of the individual-level variables were significantly associated with HF in the full models. The HRs for HF were higher for men and women with low education, low family income, country of birth outside Sweden, or those who had moved or had a hospitalisation for comorbidities (Supplementary Table S2).

DISCUSSION

The main finding of this study was that the risk of incident HF is higher among patients with DM living in deprived neighbourhoods than among patients with DM living in less deprived/affluent neighbourhoods. This difference was attenuated but remained significant, after adjustment for the individual-level sociodemographic variables and traditional cardiovascular risk factors (COPD, alcoholism and related liver disorders, diabetes, obesity). It is important to note that a significant number of individuals changed their place of residence, and level of neighbourhood deprivation, during the follow-up. Many of the individuals were, however, elderly and it was to be expected that some of them would downsize by moving from their larger house to an apartment, such as in the case of being widowed. We adjusted our analyses for the move of participants to a neighbourhood of differing level of deprivation, and the relationship between neighbourhood deprivation and HF remained significant in the DM patients.

Living in highly deprived neighbourhoods has been shown to be associated with an increased risk of morbidities, such as that of coronary heart disease11, and DM14. In our study, we found that the incidence rates of HF in DM patients increased with the level of neighbourhood deprivation.

The causal pathways between neighbourhood deprivation and cardiovascular health outcomes are, however, not fully understood10,15–17. Several possible mechanisms could, however, explain our findings. One possible mechanism is the potential differences between socioeconomic groups in knowledge, attitudes and beliefs that could lead to differences in lifestyle in DM patients; these differences may partly explain differences in morbidity risk across socioeconomic strata16,18,19. For instance, a UK study showed that cardiovascular disease risk factors, including obesity and smoking, were more common among patients with DM living in deprived neighbourhoods than among those living in less deprived/affluent neighbourhoods18. Similar results were found in another neighbourhood study of cardiovascular disease risk factors among patients with DM19. A Swedish study showed that cardiovascular disease risk factors, including physical inactivity, obesity, and smoking, were more common among individuals living in deprived neighbourhoods than among those living in less deprived/affluent neighbourhoods16. It is possible that sociocultural norms regarding diet, smoking and physical activity could vary between neighbourhoods and affect the health of the residents and the consequent risk for disease.

HF is one of the most common comorbidities of DM. Glucose-lowering therapies that can prevent HF or improve outcomes in patients with established HF are of critical importance among patients with DM20. Although Sweden has a universal health care system, it is possible that there still are differences between neighbourhoods regarding the access of glucose-lowering therapies affecting HF risk of DM. These differences could be related both to individual socioeconomic differences that may affect people’s possibilities to buy prescribed medicine21 and poorer access to primary health care in deprived neighbourhoods22. The findings of previous studies together with the findings of the present study illuminate the need for improving health in low resource settings, which is underway in Europe23. For example, a UK study showed social differences in both the prevalence of DM as well as impaired glucose regulation24.

There are also other potential mechanisms behind our findings. The levels of social capital, which in turn are related to social norms, beliefs and attitudes, are lower in deprived neighbourhoods25. The crime levels are also higher in deprived neighbourhoods26, which could increase psychosocial stress and reduce physical activity due to fear of going outside. It has also been suggested that neighbourhood goods, services and resources are poorer in deprived neighbourhoods. However, a previous study of ours showed that the availability of potentially health-promoting goods, services and resources is higher, not lower, in deprived neighbourhoods27.

Our study has a number of strengths. Our large cohort included practically all patients with diabetes (30 years and older) in Sweden during the study period, which increases the generalisability of our results. Another strength is the personal identification number that is assigned to each individual in Sweden. This gave us the opportunity to follow the patients without any loss to follow-up. The outcome data were based on clinical diagnoses, registered by physicians, rather than self-reported data, which eliminated any recall bias. An additional key strength was the access to SAMS units that defined geographic boundaries of our study neighbourhoods. The SAMS units were small (in the order of 1000–2000 persons) and each unit consisted of relatively homogenous types of buildings. In previous research, small neighbourhoods have been shown to correspond well with how the residents define their neighbourhoods28. Moreover, our data were highly complete; only 0.6% of the patients with diabetes were excluded because of missing SAMS codes. We were able to link clinical data from individual patients to national demographic and socioeconomic data. The national demographic and socioeconomic data were highly complete – less than 1% of the data were missing.

Our study also has some limitations. We had no data on several risk factors for HF, such as smoking, high-caloric diet or physical inactivity. However, some prior works on SES and HF risk have adjusted for smoking and physical inactivity and still found an independent association3,29. We had no data on quality of health care in the neighbourhood. Finally, the outcome variable (HF) was based only on hospitalizations.

Conclusions:

The findings of the present study are useful for health care workers encountering patients with DM and particularly those living in deprived neighbourhoods. Understanding the pathways between neighbourhood factors (independent of individual factors) and various health outcomes is challenging. Future research could focus on the specific pathways between neighbourhood environments and HF and how to reduce differences in HF among patients with DM living in various types of neighbourhood environments. Such research is needed in order to identify those mechanisms that may result in efficient preventive strategies and health policies in the future.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Neighbourhood socioeconomic status (SES) has been shown to be an important risk factor for heart failure among patients with diabetes mellitus.

These Hazards ratios remain significant, after adjustment for individual-level sociodemographics.

Increased rates of heart failure among adults in deprived neighbourhoods raise important clinical and public health concerns.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the CPF’s Science Editor Patrick Reilly for his useful comments on the text. This work was supported by Crafoordska stiftelsen (20171054) and Stiftelsen Promobilia (15118), the Swedish Research Council, and Forte, i.e., the Swedish Research Council for Health, Working Life and Welfare. This work was also supported by the National Heart, Lung, And Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R01HL116381 to Kristina Sundquist.

Abbreviations

- CHD

Coronary heart disease

- CI

Confidence interval

- COPD

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- DM

Diabetes mellitus

- HF

Heart failure

- HR

Hazard ratio

- ICD

International Classification of Diseases

- SAMS

Small area market statistics

- SES

Socioeconomic status

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest Statement

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Kannel WB, Hjortland M, Castelli WP. Role of diabetes in congestive heart failure: the Framingham study. Am J Cardiol. 1974;34:29–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rawshani A, Rawshani A, Franzen S, et al. Risk Factors, Mortality, and Cardiovascular Outcomes in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:633–644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Akwo EA, Kabagambe EK, Harrell FE Jr.,, et al. Neighborhood Deprivation Predicts Heart Failure Risk in a Low-Income Population of Blacks and Whites in the Southeastern United States. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2018;11:e004052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cuthbertson CC, Heiss G, Wright JD, et al. Socioeconomic status and access to care and the incidence of a heart failure diagnosis in the inpatient and outpatient settings. Ann Epidemiol. 2018;28:350–355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carlsson AC, Li X, Holzmann MJ, et al. Neighbourhood socioeconomic status and coronary heart disease in individuals between 40 and 50 years. Heart. 2016;102:775–782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Andersen AF, Carson C, Watt HC, Lawlor DA, Avlund K, Ebrahim S. Life-course socio-economic position, area deprivation and Type 2 diabetes: findings from the British Women’s Heart and Health Study. Diabet Med. 2008;25:1462–1468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ismail AA, Beeching NJ, Gill GV, Bellis MA. Capture-recapture-adjusted prevalence rates of type 2 diabetes are related to social deprivation. Qjm. 1999;92:707–710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Beeching NJ, Gill GV. Deprivation and Type 2 diabetes mellitus prevalence. Diabet Med. 2000;17:813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Krishnan S, Cozier YC, Rosenberg L, Palmer JR. Socioeconomic status and incidence of type 2 diabetes: results from the Black Women’s Health Study. Am J Epidemiol. 2010;171:564–570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sundquist K, Malmstrom M, Johansson SE. Neighbourhood deprivation and incidence of coronary heart disease: a multilevel study of 2.6 million women and men in Sweden. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2004;58:71–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Winkleby M, Sundquist K, Cubbin C. Inequities in CHD incidence and case fatality by neighborhood deprivation. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2007;32:97–106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Statistiska Centralbyrån (Statistics Sweden). Eurostat yearbook 2004. [Electronic source]. 2004; http://www.scb.se/templates/Standard____36500.asp Accessed March 27, 2006.

- 13.Gilthorpe MS. The importance of normalisation in the construction of deprivation indices. J. Epidemiol. Community Health. 1995;49 Suppl. 2:S45–S50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.White JS, Hamad R, Li X, et al. Long-term effects of neighbourhood deprivation on diabetes risk: quasi-experimental evidence from a refugee dispersal policy in Sweden.Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2016;4:517–524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aslanyan S, Weir CJ, Lees KR, Reid JL, McInnes GT. Effect of area-based deprivation on the severity, subtype, and outcome of ischemic stroke. Stroke. 2003;34:2623–2628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sundquist J, Malmstrom M, Johansson SE. Cardiovascular risk factors and the neighbourhood environment: a multilevel analysis. Int J Epidemiol. 1999;28:841–845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zoller B, Li X, Sundquist J, Sundquist K. Neighborhood deprivation and hospitalization for venous thromboembolism in Sweden. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2012;34:374–382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Connolly VM, Kesson CM. Socioeconomic status and clustering of cardiovascular disease risk factors in diabetic patients. Diabetes Care. 1996;19:419–422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Unwin N, Binns D, Elliott K, Kelly WF. The relationships between cardiovascular risk factors and socio-economic status in people with diabetes. Diabet Med. 1996;13:72–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vijayakumar S, Vaduganathan M, Butler J. Glucose-Lowering Therapies and Heart Failure in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: Mechanistic Links, Clinical Data, and Future Directions. Circulation. 2018;137:1060–1073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Skoog J, Midlov P, Beckman A, Sundquist J, Halling A. Drugs prescribed by general practitioners according to age, gender and socioeconomic status after adjustment for multimorbidity level. BMC Fam Pract. 2014;15:183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Crump C, Sundquist K, Sundquist J, Winkleby MA. Neighborhood deprivation and psychiatric medication prescription: a Swedish national multilevel study. Ann Epidemiol. 2011;21:231–237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Modesti PA, Agostoni P, Agyemang C, et al. Cardiovascular risk assessment in low-resource settings: a consensus document of the European Society of Hypertension Working Group on Hypertension and Cardiovascular Risk in Low Resource Settings. J Hypertens. 2014;32:951–960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moody A, Cowley G, Ng Fat L, Mindell JS. Social inequalities in prevalence of diagnosed and undiagnosed diabetes and impaired glucose regulation in participants in the Health Surveys for England series. BMJ Open. 2016;6:e010155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Derose KP, Varda DM. Social capital and health care access: a systematic review. Med Care Res Rev. 2009;66:272–306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sundquist K, Theobald H, Yang M, Li X, Johansson SE, Sundquist J. Neighborhood violent crime and unemployment increase the risk of coronary heart disease: a multilevel study in an urban setting. Soc Sci Med. 2006;62:2061–2071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kawakami N, Winkleby M, Skog L, Szulkin R, Sundquist K. Differences in neighborhood accessibility to health-related resources: a nationwide comparison between deprived and affluent neighborhoods in Sweden. Health Place. 2011;17:132–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bond Huie S The concept of neighbourhood in health and mortality research. Sociological Spectrum. 2001;21:341–358. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bikdeli B, Wayda B, Bao H, et al. Place of residence and outcomes of patients with heart failure: analysis from the telemonitoring to improve heart failure outcomes trial. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2014;7:749–756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.