Abstract

Chemoimmunotherapy has been the standard of care for patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia for a long time. However, over the last few years, novel agents have produced unprecedented outcomes in treatment-naïve and relapsed/refractory chronic lymphocytic leukemia. With the advent of these targeted agents, treatment options have diversified very considerably and new questions have emerged. For example, it is unclear whether these novel agents should be used as sequential monotherapies until disease progression or whether they should preferably be combined in time-limited treatment regimens aimed at achieving deep and durable remissions. While both approaches yield high response rates and long progression-free and overall survival, it remains challenging to identify patients individually for the optimal concept. This review provides guidance in this decision process by presenting evidence on sequential and combined use of novel agents and discussing the advantages and drawbacks of these two approaches.

Introduction

Chemoimmunotherapy has been the standard first-line treatment of choice for patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) for many years.1,2 However, with the advent of novel, targeted agents, the survival of CLL patients has improved markedly and treatment options have diversified, especially for patients with high-risk CLL.3–7 Recently published studies directly comparing standard chemoimmunotherapy against novel agents have demonstrated the superiority of the latter in various groups of patients.8–10 Chemoimmunotherapy still plays a role in the treatment of patients with mutated IGHV genes, in whom the combination of fludarabine, cyclophosphamide and rituximab produces a remarkably long progression-free survival (PFS) in nearly half of the patients, with the possibility of cure in those who have not relapsed beyond 10 years.11,12

With ibrutinib pushing into first-line treatment algorithms and other novel agents such as venetoclax and idelalisib proving their efficacy as monotherapy as well as in various combinations, new challenges are emerging. Information is needed to determine whether novel agents should be used in combination or as sequential monotherapies. Another burning issue is how to manage patients who are refractory to or relapse after treatment with novel agents.

In this review, we discuss currently approved treatment options as well as new approaches using novel agents and address optimal sequencing of single agents and the most promising combination treatments. Furthermore, we debate the concepts of time-limited versus indefinite treatment and offer guidance for treatment decisions in routine care of patients.

Approved targeted agents in chronic lymphocytic leukemia

BTK inhibitors

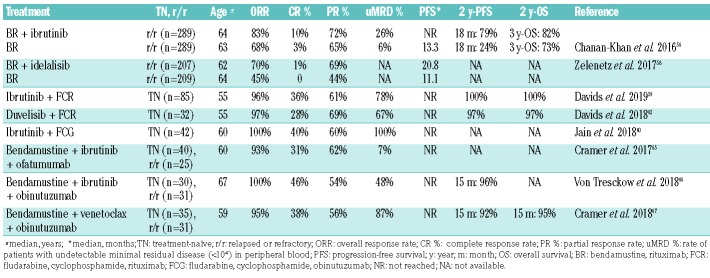

Ibrutinib is an inhibitor of Bruton tyrosine kinase (BTK), which is an intracellular protein downstream of the B-cell receptor. Ibrutinib has been approved for and implemented in the treatment of previously untreated and relapsed/refractory (r/r) CLL patients following the impressive results of the pivotal RESONATE-2 trial.3,13,14 The phase III trial demonstrated markedly prolonged PFS and overall survival (OS) in ibrutinib-treated patients compared to patients treated with chlorambucil monotherapy. The superiority of ibrutinib was shown independently of genetic subgroups and a recent follow-up documented an overall response rate (ORR) of 92% and a 2-year PFS of 89% in the ibrutinib arm.15 Data from the first trial investigating indefinite ibrutinib treatment in young, fit CLL patients versus the standard of care in these patients (fludarabine, cyclophosphamide and rituximab) were published recently.9 The ECOG-ACRIN E1912 intergroup trial showed significant PFS and OS advantages for patients treated with ibrutinib plus rituximab (Table 1). Improved survival was observed across all analyzed subgroups except for IGHV-mutated patients. In another recently published study, Woyach and colleagues evaluated the efficacy of ibrutinib alone or in combination with rituximab in CLL patients ≥65 years and compared it to that of bendamustine plus rituximab.10 The study showed a clear PFS advantage for both ibrutinib and ibrutinib plus rituximab compared with bendamustine plus rituximab. Due to the planned cross-over no significant survival differences were seen in the IGHV-mutated group or with regards to OS. The addition of rituximab to ibrutinib did not result in an improved survival.

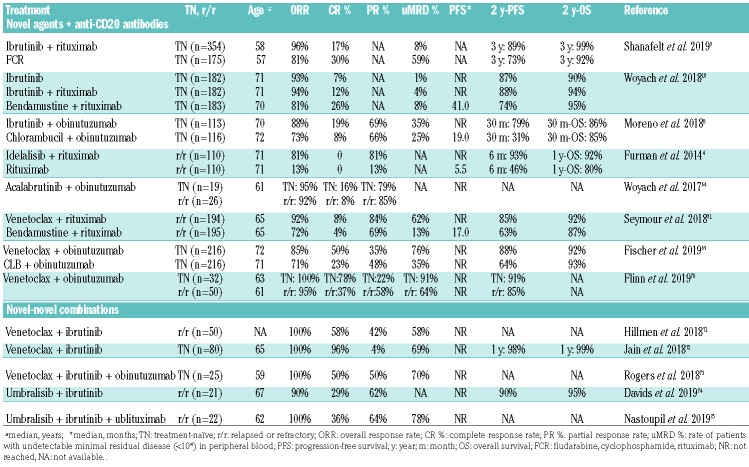

Table 1.

Trials using chemotherapy-free combination treatments in chronic lymphocytic leukemia

Consequently, the place of ibrutinib in the first-line treatment of most groups of patients with CLL has been consolidated and the responses seem to be durable as well. A 5-year follow-up of a phase II trial initiated by the National Institutes of Health evaluating ibrutinib as first-line therapy in CLL showed a 5-year PFS of 74.4% in treatment-naïve patients with TP53 mutations or deletions and 100% in treatment-naïve patients without TP53 mutations.16 Although ibrutinib monotherapy is currently the most and best evaluated novel substance and indisputably yields impressive outcomes, its continued administration is associated with several problems. In the above-mentioned study in patients with high-risk CLL, the cumulative incidence of resistance-conferring BTK or PLCγ2 mutations at 5 years ranged between 22.6% and 66.7% depending on the risk group.16,17 Similar rates were observed in a French real world cohort: after a median of 3.5 years of ibrutinib treatment, BTK mutations were found in 57% of the patients.18 The same study showed that 3 years after initiation of ibrutinib treatment, only 31% of the patients remained on the drug. The incidence of ibrutinib-related toxicities and associated treatment discontinuation vary significantly between clinical trials and so-called real world experiences. A retrospective analysis reported toxicity-related treatment discontinuations in 128 of 616 patients (21%) with a median follow-up of 17 months in their comprehensive real-world analysis while the toxicity-related treatment discontinuation rate in the above-mentioned phase II trial in high-risk CLL was only 6%.16,19 Atrial fibrillation has been reported in several trials as a cause of treatment interruption. In a retrospective analysis, the 5-year incidence of atrial fibrillation was 21%.16 Another pooled analysis of multiple clinical trials estimated a 3-year cumulative incidence of atrial fibrillation of 13.8% among ibrutinib-treated patients.20

Other BTK inhibitors have been developed to overcome these commonly encountered difficulties, such as the development of resistance mutations and the discontinuation of treatment due to adverse drug effects. While second-generation inhibitors such as substance ARQ 531 promise efficacy in the context of BTK C481S mutations, more specific inhibitors, including acalabrutinib and zanubrutinib, appear to cause fewer adverse off-target effects.21–24 Direct, randomized comparisons of acalabrutinib (NCT02477696) and zanubrutinib (NCT03734016) against ibrutinib are currently ongoing.

PI3K inhibitors

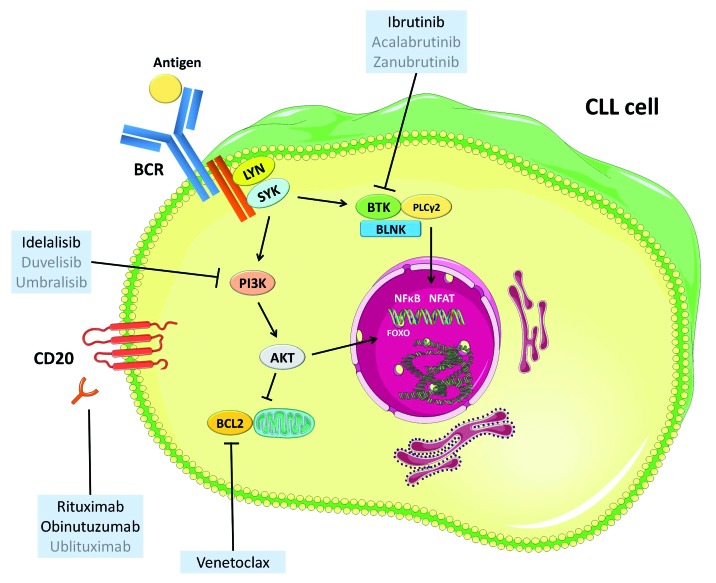

Phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K)γ is the target of the kinase inhibitor idelalisib and a downstream kinase of the B-cell receptor that stimulates the proliferation and survival of CLL cells (Figure 1). The combination of idelalisib with rituximab is approved for the treatment of r/r CLL as well as for the first-line treatment of patients with del(17p) and/or TP53 mutations for whom no other therapies are appropriate. Idelalisib has shown some activity as a single agent in r/r CLL and was combined with rituximab in a prospective randomized study against rituximab monotherapy.4,25 The median PFS in the placebo group was 5.5 months and was not reached in the rituximabide-lalisib arm [hazard ratio (HR) for disease progression or death 0.15, P<0.001]; the ORR was 81% with idelalisib, but only 13% in the rituximab arm. Following these encouraging results, the combination was investigated in the first-line setting. In a phase II study, 64 patients were treated with rituximab and idelalisib with a median treatment duration of 22.4 months.26 The ORR was 97%, including 19% complete responses (CR) and the estimated 3-year PFS was 83%. However, significant severe adverse events of this regimen were reported. Diarrhea and colitis occurred in 61% of patients, skin rash in 58%, fever in 42%, nausea in 38% and transaminitis in 67%.27 In large phase III trials, an increased mortality was observed in the idelalisib-containing arms which led to premature discontinuation of other trials and a re-evaluation of the substance by regulatory authorities.28

Figure 1.

Targets of currently approved (black) and investigated (gray) novel agents. CLL: chronic lymphocytic leukemia; BCR: B-cell receptor. This figure was produced by M. Fürstenau using servier medical art (smart.servier.com).

Other kinase inhibitors targeting the PI3K pathway are umbralisib and the dual PI3K inhibitor duvelisib. While umbralisisb treatment is not yet approved, the use of duvelisib has been approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). The efficacy of duvelisib, an oral inhibitor of PI3Kδ and PI3Kγ, was demonstrated in a phase I study that included 55 r/r CLL patients of whom 56% responded to treatment.29 The results of the phase III DUO study, which tested the efficacy and safety of duvelisib versus ofatumumab, were recently published: duvelisib was associated with a significantly prolonged PFS compared to ofatumumab (13.3 vs. 9.9 months, HR=0.52, P<0.0001) and a superior ORR (74 % vs. 45 %, P<0.0001). The PI3Kδ inhibitor umbralisib demonstrated promising activity in an initial phase I trial while showing a more favorable safety profile than other PI3K inhibitors with a lower incidence of autoimmune-like adverse events.30

BCL2 inhibitors

Venetoclax is an oral B-cell lymphoma 2 (BCL2) inhibitor and was recently approved for the treatment of patients with r/r CLL in combination with rituximab.31 Before the approval of the combination therapy, venetoclax was used as an indefinite monotherapy in patients who relapsed after ibrutinib treatment and patients with TP53 aberrations.7 With the universal approval of venetoclax plus rituximab as second-line therapy, indefinite venetoclax monotherapy will be less relevant in the near future. Nonetheless, it is worthwhile looking at extended follow-up data of venetoclax monotherapy trials.

The results of a phase II study evaluating venetoclax in 158 mostly r/r CLL patients with 17p deletions was recently published.32 The median duration of venetoclax treatment was 23.1 months (range, 0-44.2 months) and the ORR was 77% (122 of 158 patients; 20% CR) while the 2-year PFS was 54% [95% confidence interval (95% CI): 45% to 62%]. Forty-eight (30%) of the 158 patients achieved a minimal residual disease (MRD) status below 10−4 at least once in the course of the study. More detailed MRD data showed that, in patients receiving venetoclax monotherapy, MRD status was closely associated with PFS. Patients who achieved undetectable MRD during treatment had significantly longer PFS than patients with intermediate or high MRD levels.33 This association had previously only been reported for chemoimmunotherapy regimens.34 While these results demonstrate the relevance of venetoclax for patients with 17p deletions, venetoclax monotherapy is still only approved in the first-line setting in patients ineligible for ibrutinib treatment.

In relapsed CLL, venetoclax was approved in combination with rituximab based on the data from the MURA-NO study that tested this 24-month long combination treatment against bendamustine plus rituximab in a population of 389 CLL patients.31 With a median follow-up of 23.8 months, PFS among the patients treated with venetoclax plus rituximab was clearly superior to that of patients treated with bendamustine plus rituximab (HR=0.17; 95% CI: 0.11-0.25; P<0.0001): the estimated 2-year PFS was 84.9% for patients treated with venetoclax plus rituximab and 36.3% for those treated with bendamustine plus rituximab. Venetoclax plus rituximab also produced a significantly prolonged OS (HR=0.48; 95% CI: 0.25-0.90) and an impressive ORR of 93.3% compared to 67.7% with bendamustine plus rituximab (difference= 25.6%; 95% CI: 17.9-33.3%). Venetoclax plus rituximab also led to higher rates of undetectable MRD in peripheral blood (62.4% vs. 13.3% after 9 months). Most importantly, the MURANO study established the feasibility of a time-limited chemotherapy-free treatment regimen by demonstrating that the majority of MRD-negative remissions were sustained after the end of the study treatment.35 With an extended median follow-up of 36 months, 130 (67%) of 194 patients completed the 2-year treatment and with a median observation time of 9.9 months after completion of treatment with venetoclax plus rituximab, only 16 of 130 patients (12%) showed disease progression.

While the occurrence of clinical tumor lysis syndromes was a dreaded and common event in the early experiences with venetoclax, the risk of these syndromes has now been successfully mitigated by introducing a ramp-up schedule and repeated testing of tumor lysis syndrome parameters within the first 24 h after each ramp-up.7 A recent comprehensive safety analysis of three trials using venetoclax monotherapy showed an incidence of laboratory tumor lysis syndrome of only 1.4% while no clinical tumor lysis syndrome occurred.36 Most adverse events were hematologic toxicities such as neutropenia (40% of all patients) and thrombocytopenia (21%), gastrointestinal disorders including diarrhea (41%) and nausea (39%) as well as upper respiratory tract infections (25%).

As previously reported for ibrutinib, continued drug exposure may result in the development of specific resistance mutations in the context of indefinite venetoclax treatment. A venetoclax-specific resistance mutation in the BCL2 gene was recently reported.37 Of 15 patients whose disease progressed during venetoclax treatment, seven showed a heterozygous nucleotide variant (Gly101Val) in BCL2 that impaired binding of venetoclax to the protein. The mutation was detected as early as 25 months before clinically apparent CLL progression. Another study showed various other molecular aberrations in patients who developed resistance upon BCL2-inhibition by venetoclax, including cancer-related genes such as TP53, BRAF and CD274.38

Sequential use of novel agents

Despite the long PFS that novel agents have produced, most patients will probably require a second-line treatment after the first novel agent either because of disease progression or because of toxicity-related treatment discontinuation. As novel agents have only been approved recently, there is limited evidence on how best to sequence these agents and how to treat patients who relapse after these therapies. Available data are largely based on retrospective cohort studies and registry data.

Mato et al. systematically assessed treatment sequences in a large cohort of patients treated with ibrutinib or venetoclax.39 Ibrutinib given as a first kinase inhibitor yielded better outcomes than idelalisib, while in the setting of ibrutinib failure, venetoclax produced superior survival compared with idelalisib and chemoimmunotherapy. Jones and colleagues confirmed this observation in their analysis of 127 patients who received venetoclax after kinase inhibtor failure with a median PFS of 24.7 months for venetoclax treatment after ibrutinib and an estimated 1-year PFS of 79% for venetoclax after idelalisib failure.40 Within another analysis, Mato and colleagues assessed outcomes in patients who had previously been treated with idelalisib or ibrutinib with regard to the reason of prior treatment discontinuation.19 The main reason for discontinuation of treatment with a kinase inhibitor was toxicity (51%), followed by disease progression (29%) and Richter transformation. Patients who were retreated due to intolerance of the previously used kinase inhibitor had significantly better outcomes than patients whose disease had progressed during the kinase inhibitor treatment.

Patients in whom venetoclax treatment fails have not yet been extensively analyzed. In a recently published analysis, 204 venetoclax-treated patients were evaluated of whom about 47% discontinued treatment due to progressive disease, 21% due to Richter transformation and 11% because of mostly hematologic adverse events.41 Nineteen patients who were subsequently treated with a kinase inhibitor showed a good ORR of 69% and a median PFS that was not reached after a median follow-up of 7 months. First data from patients progressing on the MURANO trial who were subsequently treated with ibrutinib indicate that this kinase inhibitor can be successfully used after venetoclax.42 Of eight patients who were included in this analysis, seven responded to ibrutinib (6 partial responses, 1 complete response).

Furthermore, alternate kinase inhibitors were investigated in patients who were intolerant to either ibrutinib or idelalisib.43,44 Thirty-three patients who discontinued ibrutinib treatment due to toxicities were treated with acalabrutinib and showed an ORR of 76%. The median PFS had not been reached after a median follow-up of 9.5 months. During this time only 6% of the ibrutinib-intolerant patients discontinued treatment with acalabrutinib due to adverse events.43 In a similar study, 36 BTK inhibitor-intolerant and four PI3K inhibitor-intolerant patients were treated with umbralisib; four of these patients discontinued treatment due to an adverse event within a median follow-up of 7 months.44

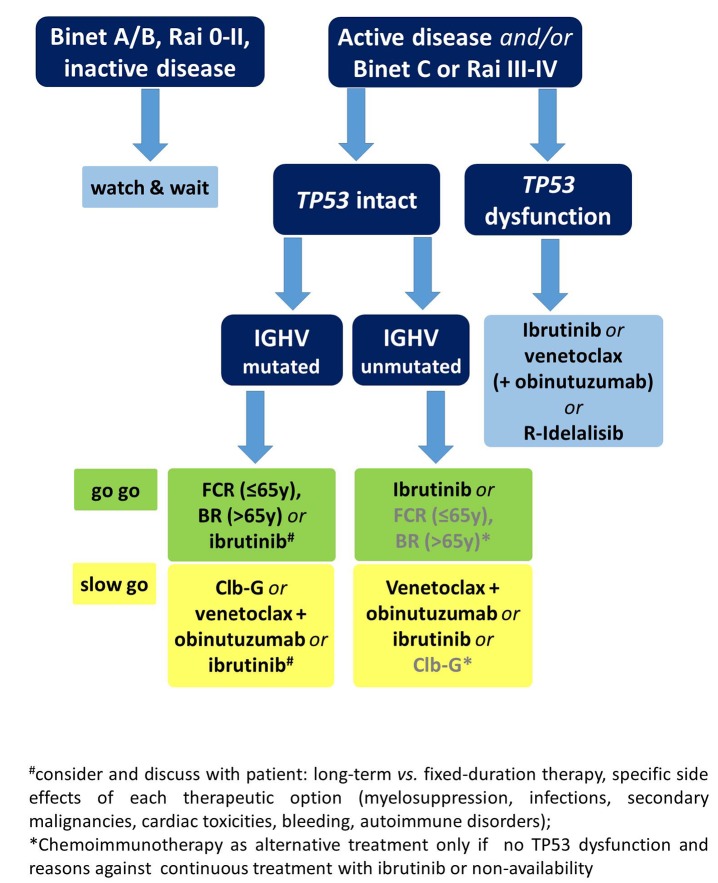

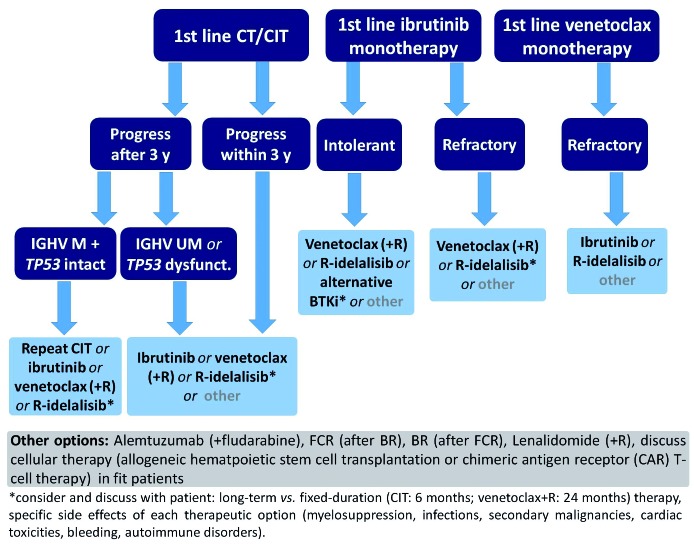

Prospective clinical trials including long-term follow-ups are urgently needed to establish an optimal sequencing strategy. Nonetheless, some conclusions on the sequence of therapy can be drawn based on the limited, existing data. Venetoclax-containing regimens appear to be superior after ibrutinib failure while ibrutinib seems the best option after venetoclax.39–41 Patients in whom idelalisib fails can be treated equally with either ibrutinib or venetoclax. When ibrutinib treatment is discontinued due to toxicities, changing to an alternative BTK inhibitor, such as acalabrutinib, can be considered, where available. However, other factors must also be taken into account when deciding on a treatment sequence. These factors include the genetic risk profile, specific co-morbidities and co-medications as well as the expected compliance and personal treatment preference of the patient. Figures 2 and 3 show proposed treatment algorithms based on the available evidence and current approval status of the drugs.

Figure 2.

Proposed algorithm for first-line treatment using approved options in clinical practice. y: years; R: rituximab; FCR: fluradabine, cyclophosphamide, rituximab; BR: bendamustine, rituximab; Clb-G: chlorambucil, obinutuzumab.

Figure 3.

Proposed sequencing of therapy according to first-line treatment; approved options. CT: chemotherapy; CIT: chemoimmunotherapy; y: years; M: mutated; UM: unmutated; R: rituximab; BTKi: Bruton tyrosine kinase inhibitor.

Limitations of monotherapy with novel agents

Optimal sequencing of single agents ideally leads to durable remissions with each new substance while other effective substances are saved for the next line of treatment. In reality, however, this is often not the case.

Retrospective and registry data show markedly higher discontinuation rates of monotherapy with ibrutinib or venetoclax than those documented in the pivotal clinical trials, either due to disease progression, toxicities or other long-term adherence issues.3,15,16,19,45 After several years of exposure to ibrutinib, the incidence of BTK and PLCγ2 mutations appears to increase drastically and certain toxicities, such as cardiac arrhythmias, seem to occur at a constant frequency during ibrutinib treatment.16,18–20,37,46,47 In the long-term follow-up of the RESONATE trial, atrial fibrillation occurred in 11% of the ibrutinib-treated patients with a median follow-up of 44 months. While hematologic toxicities and infections occurred mostly in the first year of ibrutinib treatment and decreased afterwards, hypertension and rare major hemorrhages were seen constantly during the following years.48

Another crucial drawback of indefinite monotherapy is the financial burden, as all novel agents approved for use in CLL are extremely costly compared to established treatment options such as chemoimmunotherapy.49 Furthermore, kinase inhibitor monotherapy rarely leads to complete and deep molecular remissions due to various mechanisms of adaptation that have recently been described.50

For these reasons, efforts have been made to design time-limited combination treatments that, despite their limited duration, achieve deep and long-lasting remissions. The only approved treatment concepts that meet these criteria and show a favorable safety profile are the 24-month fixed-duration combination of venetoclax and rituximab and the 12-month fixed-duration combination of venetoclax and obinutuzumab.31 A multitude of different combination treatments containing novel agents are currently being investigated.

Undetectable minimal residual disease as a treatment goal of new combination therapies

In 2016, the European Medicines Agency accepted the use of undetectable MRD as a surrogate for PFS and as an intermediate endpoint in CLL trials. This decision was based on large analyses of chemoimmunotherapy studies that demonstrated a strong association between MRD status and PFS and established undetectable MRD as an independent prognostic factor for PFS and OS.34,51–55 Recently the predictive value of undetectable MRD was confirmed in the context of treatment with several new substances.

An analysis of venetoclax monotherapy showed that 2-year PFS rates were significantly higher in patients who achieved undetectable (<10−4) or intermediate MRD (≥10−4 to <10−2) than in patients who never achieved MRD <10−2 (92.8%, 84.3%, and 63.2%, respectively).33 Similarly, the recently published follow-up of the MURANO study underscored the predictive value of MRD status in the context of venetoclax plus rituximab treatment.35 In con trast, the complete remission rate with ibrutinib monotherapy increased with a significant delay over time and reached 28% after a median time of 60 months. Undetectable MRD is still rarely achieved and in clinical trials evaluating ibrutinib therapy no correlation between MRD status and survival has been established so far.16

Since low MRD levels promise longer PFS and, presumably, treatment-free survival, the achievement of the lowest possible MRD level represents a desirable treatment goal. With chemoimmunotherapy the eradication of MRD below the detection limit of one CLL cell per 10,000 normal leukocytes (<10−4) could only be reliably achieved by intensive treatment regimens (e.g. fludarabine, cyclophosphamide and rituximab), which were not tolerable for the majority of elderly CLL patients with comorbidities.1,2 With the increasing availability of new substances, high rates of MRD-negative CR can also be achieved in older patients with comorbidities (Table 1).

Combinations

Chemoimmunotherapy plus novel agents

As undetectable MRD and CR are not commonly achieved with ibrutinib alone, several studies have combined the BTK inhibitor with chemoimmunotherapy to increase efficacy (Table 2). In the recently published follow-up of the HELIOS trial evaluating ibrutinib together with bendamustine plus rituximab versus bendamustine plus rituximab only, the reported rate of undetectable MRD at 36 months was 26.3% in the ibrutinib, bendamustine and rituximab arm and increased over time.56,57 Undetectable MRD status was associated with significantly improved PFS (3-year PFS rate: 88.6% for patients with undetectable MRD vs. 60.1% for patients with MRD ≥10−4). However, no termination of ibrutinib therapy was planned according to the study protocol, even when MRD was no longer detectable.

Table 2.

Trials using novel agents in combination with chemoimmunotherapy as first or further line therapy for CLL.

A similar concept was tested with the PI3Kδ inhibitor idelalisib in combination with bendamustine plus rituximab.58 While idelalisib together with bendamustine plus rituximab produced a significantly improved PFS compared with bendamustine plus rituximab only (median PFS 20.8 vs. 11.1 months), the triple combination was associated with an increased risk of severe infections, limiting its use in clinical practice.

Various phase II studies have evaluated the addition of kinase inhibitors to chemoimmunotherapy in young and fit, treatment-naïve CLL patients. Davids and colleagues reported an impressive rate of undetectable MRD in bone marrow of 78% and a CR rate of 36% after six cycles of fludarabine, cyclophosphamide and rituximab and 2 years of continuous ibrutinib.59 Another trial evaluated the MRD-guided use of frontline therapy with ibrutinib, flu-darabine, cyclophosphamide and obinutuzumab in patients with a favourable genetic risk profile (IGHV-mutated, no TP53 aberrations).60 After three courses of the quadruple combination, treatment was continued with either nine cycles of ibrutinib plus obinutuzumab or three cycles of ibrutinib plus obinutuzumab and six cycles of ibrutinib only, depending on post-chemoimmunotherapy MRD status. Undetectable MRD at 1 year led to the discontinuation of all therapy. All 28 patients who completed 12 months of treatment had undetectable MRD and stopped therapy per protocol: the CR rate was 86% at that time point. Michallet et al. evaluated a similar scheme in a larger study including previously untreated CLL patients with mutated or unmutated IGHV. Induction treatment consisted of 6 months of ibrutinib plus obinutuzumab followed by 3 months of ibrutinib.61 After this treatment, MRD was tested and patients with MRD-negative CR or CR with incomplete hematologic recovery (CRi) continued treatment with ibrutinib for another 6 months while all other patients received an intensified regimen with four cycles of the quadruple combination (ibrutinib, fludarabine, cyclophosphamide and obinutuzumab) and ibrutinib until month 16. With this approach, only 12% of the patients were in MRD-negative CR or CRi: after 9 months and could avoid intensive chemoimmunotherapy.

The dual PI3K inhibitor duvelisib was also evaluated in combination with fludarabine, cyclophosphamide and rituximab therapy. However, this regimen induced a slightly lower CR rate of 26% and a rate of undetectable MRD in bone marrow of 67%.62 Although the most frequent adverse events were hematologic toxicities, several immune-mediated toxicities, including transaminitis (grade 3: 34%), arthritis (9%), colitis (6%), pericarditis and pancreatitis (both 3%), were also reported.

Although the addition of kinase inhibitors to conventional chemoimmunotherapy regimens yields significant undetectable MRD and CR rates in selected populations of patients, these combinations have not yet been tested against kinase inhibitor monotherapy. This limits the practical relevance of these observations in the light of the impressive outcomes of single agent ibrutinib. In addition, toxicity rates with these more intensive combinations cannot be neglected. Treatment of elderly patients with comorbid conditions, in particular, is probably more difficult due to the toxicity rates.

Novel agents plus anti-CD20 antibodies

While idelalisib is specifically approved in combination with anti-CD20 antibodies, ibrutinib has so far not been approved as part of a combination treatment due to ambiguous study results.4,10,63 The combination of ibrutinib plus rituximab has been tested in randomized settings in phase II and phase III trials.10,63 Burger and colleagues conducted a randomized trial of ibrutinib versus ibrutinib plus rituximab in 208 CLL patients of whom 181 had r/r CLL.63 The other 27 patients included were treatment-naïve, but had high-risk, unfavorable genetics, defined by del(17p) or TP53 mutation. The study showed no difference between ibrutinib plus rituximab and ibrutinib in either PFS (3-year PFS: 86.9% vs. 86%), ORR (92.3% for both) or CR rate (26% vs. 20.2%). However, patients treated with ibrutinib plus rituximab showed higher rates of undetectable MRD and achieved their remissions faster than patients treated with ibrutinib only. A phase III trial (ALLIANCE) that tested ibrutinib and ibrutinib plus rituximab against bendamustine plus rituximab in older patients showed almost identical efficacy data for both ibrutinib-containing arms.10 While these data support the conclusion that there is no clear benefit of adding rituximab to ibrutinib, no randomized comparison has been performed so far comparing obinutuzumab plus ibrutinib versus ibrutinib monothera-py. The iLLUMINATE trial evaluated ibrutinib plus obinutuzumab in comparison to chlorambucil plus obinutuzumab. The combination of ibrutinib plus obinutuzumab was significantly superior to the chemoimmunotherapy regimen with a PFS at 30 months of 79% versus 31% (P<0.0001), but unfortunately a third arm with ibrutinib monotherapy was missing. Hence the benefit of the addition of obinutuzumab is not clear, particularly because no treatment stop was planned in the case of CR, which was achieved in 19% of the patients receiving ibrutinib plus obinutuzmab. First data from a phase Ib/II study combining acalabrutinib and obinutuzumab were impressive with an ORR of 93%, but also in this trial there was no direct comparison to acalabrutinib monotherapy.64

Two identically designed phase II trials evaluated the use of ibrutinib plus obinutuzumab and ibrutinib plus ofa-tumumab after an optional debulking with bendamustine including a planned termination of treatment if peripheral blood samples showed undetectable MRD at two consecutive time-points. While 48% of all ibrutinib plus obinutuzumab-treated patients had undetectable MRD at the final restaging, only 14% achieved this status after ibrutinib plus ofatumumab treatment.65,66

In contrast to ibrutinib, the addition of rituximab to venetoclax has produced unprecedented MRD-negative response rates in r/r CLL leading to its broad approval in the r/r setting.31 In the pivotal MURANO trial comparing bendamustine plus rituximab versus 24 months of venetoclax plus rituximab 64% of the patients treated with the latter combination had no detectable MRD after 24 months of treatment and this status was sustained in the majority, with a median follow-up of approximately 10 months.35 This study was the first to establish a chemotherapy-free time-limited treatment regimen in CLL.

Even higher response rates were observed when venetoclax was combined with obinutuzumab. The CLL2-BAG trial combined an optional upfront debulking with bendamustine with an 8-month induction treatment and a MRD-guided maintenance phase, both consisting of venetoclax and obinutuzumab.67 At the end of induction treatment, 60 of 63 patients (95%) had responded to treatment and 87% of the patients had no detectable MRD below 10−4. The remissions seem durable after undetectable MRD-triggered end of treatment even in patients with high-risk genetic features.68 The recently published phase III CLL14 trial confirmed the efficacy of this combination treatment in a comorbid patient collective when tested against chlorambucil plus obinutuzumab. A 12 month fixed-duration treatment with venetoclax and obinutuzumab produced an unprecedented uMRD rate of 76% and an estimated 2-year PFS of 88%.69 In a recent phase Ib study, venetoclax and obinutuzumab were combined for 6 months and followed by venetoclax treatment for either 1 year in the first-line cohort or until disease progression in the r/r cohort.70 The overall best response rate was 95% in r/r CLL patients and 100% in those treated first-line. Undetectable MRD rates in the peripheral blood were 64% and 91%, respectively, ≥3 months after the last dose of obinutuzumab.

Inhibitors in combination, including triple combinations

Considering the impressive single agent activity of kinase inhibitors and venetoclax in CLL and their ability to induce deep and durable remissions when combined with an anti-CD20 antibody, it seems obvious to test novel-novel combinations to further increase efficacy by synergistically tackling the CLL cell in different vital pathways (Figure 1).

The phase II CLARITY trial tested a time-limited and MRD-guided oral combination treatment of ibrutinib and venetoclax in 40 patients with r/r CLL.71 After 8 weeks of ibrutinib treatment, venetoclax was added with the established 5-week dose escalation scheme. All patients responded to treatment (CR/CRi rate: 58%) and 23 of 40 patients (58%) had no detectable MRD in peripheral blood after 12 months of combined therapy. The same combination in a fixed-duration 24-month strategy was investigated in 80 treatment-naïve patients with CLL.72 After 12 months of combined venetoclax and ibrutinib the CR/CRi rate was 96% and 69% of the patients had no detectable MRD in the bone marrow. In both trials, the rates of undetectable MRD increased during the course of treatment, promising higher rates with longer follow-up.

Rogers and colleagues recently reported the preliminary outcomes of their phase II trial investigating the triple combination of obinutuzumab, ibrutinib and venetoclax in treatment-naïve and r/r CLL.73 In the first month of treatment, only obinutuzumab was administered. Ibrutinib was added in month 2 and venetoclax was added in month 3. After 12 months of combined treatment, the ORR was 88% in the r/r patients and 84% in the treatment-naïve cohort while 67% of treatment-naïve patients and 50% of all r/r patients had no detectable MRD in bone marrow and peripheral blood.

The first study successfully using two novel agents that directly target the B-cell receptor pathway combined umbralisib with ibrutinib and produced an ORR of 90% (CR: 29%) and a 2-year PFS of 90%.74 In contrast to prior studies that combined multiple kinase inhibitors, this combination was well-tolerated and no dose-limiting toxicities were observed. The same combination plus ublituximab was assessed safe and active in a phase I study in which the ORR was 100% among 22 previously treated patients with CLL or small lymphocytic lymphoma. The median duration of response was 22.7 months.75

Checkpoint inhibitor monotherapy has shown limited efficacy in CLL but promising activity in Richter transformation.76 A phase II study investigated the combination of ibrutinib and nivolumab in patients with high-risk CLL or Richter transformation.77 While the combination showed promising efficacy in Richter transformation, it produced an ORR of 61% in the high-risk CLL group, which is comparable to that achieved with single-agent ibrutinib.

Discussion

Ibrutinib monotherapy has produced unprecedented PFS and OS in various groups of CLL patients.3,9,10,13,14 Being the only novel agent that has been broadly approved in the first-line setting, it remains the most widely used novel agent in clinical routine. For the consequently increasing number of patients relapsing after ibrutinib, current evidence indicates that optimal sequencing of novel agents can lead to long PFS and OS with an overall favorable safety profile.39–41,78 The bar in terms of PFS has been raised high by the sequence of frontline ibrutinib followed by venetoclax.

However, continued monotherapy is associated with some drawbacks including the development of resistance mutations, an increased financial burden, cumulative toxicities, and long-term adherence issues.18,19,36,38,45,47,50,79 These factors underscore the need for further development of time-limited treatment concepts that lead to deep and durable remissions, ideally with long treatment-free intervals.

With the broad approval of venetoclax plus rituximab for r/r CLL, a first chemotherapy-free fixed-duration regimen has pushed into clinical practice and the even shorter combination treatment of venetoclax and obinutuzumab that has proven its striking efficacy in treatment-naïve patients has just followed. Based on the CLL14 data comparing chlorambucil plus obinutuzumab versus fixed-duration venetoclax plus obinutuzumab for 12 months another venetoclax combination therapy has been approved by the FDA for the frontline treatment of patients with CLL.

The essential question of how durable achieved remissions are after stopping combination treatment was in part answered by two recently published long-term followups. In the MURANO trial, the majority of MRD-negative remissions were sustained with a median follow-up of 9.9 months after the end of study treatment.35 Furthermore, Cramer et al. documented that 13 of 17 high-risk CLL patients (17p deletion/TP53 mutation) who achieved undetectable MRD after a time-limited treatment with either venetoclax plus obinutuzumab or ibrutinib plus obinutuzumab had ongoing remissions after a median observation time of 16 months after the end of study treatment.68

While these treatment-free phases are certainly desirable from a patient’s point of view, their effect on clonal evolution of CLL remains largely unknown. It is conceivable though that shorter exposure to ibrutinib and venetoclax might be associated with a lower incidence of drug-specific resistance mutations as most of these seem to appear later in the course of monotherapy.16,18,37,38,47,80,81 The absence of resistance mutations and treatment-free intervals could allow for re-exposure of patients to the same combination treatment, potentially with a similar efficacy as before.

Comprehensive safety analyses are much needed, particularly in the context of novel-novel combinations to detect treatment-specific toxicities that might not be detected in smaller phase II trials.27,36,82 As ibrutinib alone seems to be associated with an increased incidence of certain opportunistic infections, it is conceivable that this specific risk might be even higher when this drug is combined with additional substances that influence the immune system.83,84

Detailed pharmacokinetic analyses are also warranted to optimize combination treatments as kinase inhibitors and venetoclax might interact due to their CYP-dependent metabolism.85 A recent study found that even reduced doses of ibrutinib lead to complete BTK occupancy, possibly clearing the way for lower dosed treatment with fewer off-target effects.17

Results from the currently recruiting phase III FLAIR (2013-001944-76) and GAIA/CLL13 (NCT02950051) trials are eagerly awaited to see whether time-limited combinations of novel agents prove themselves superior in a direct comparison with standard first-line regimens. While the GAIA/CLL13 trial is investigating various venetoclax-based combinations in young and fit patients, the FLAIR study will show, in a similar group of patients, whether the promising oral combination of ibrutinib plus venetoclax is superior to the current standards, ibrutinib monotherapy and fludarabine, cyclophosphamide and rituximab.

However, it will probably take more well-designed, randomized trials and particularly long-term follow-up data as well as detailed analyses of PFS2 or 3 after combination treatments in order to determine conclusively whether sequential single-agent therapy or novel combination therapy is superior to the other.

With upcoming combination therapies in contrast to continuous monotherapies, the optimal selection of individual treatment for each patient is challenging. For instance, patients with a complex karyotype who might be more susceptible to the development of resistance mutations under single-agent monotherapy could be eligible for novel combinations.86 Ahn and colleagues recently presented a risk score that predicts survival and the occurrence of resistance mutations in the context of ibrutinib monotherapy, whereas Visentin and colleagues developed a score that predicts atrial fibrillation during ibrutinib treatment.17,87 These are just two examples of how more available information will lead to a further diversification and personalization of treatment options. It is, therefore, crucial to work on identifying additional risk factors and understanding disease biology and clonal evolution of CLL in the context of novel agents.

Footnotes

Check the online version for the most updated information on this article, online supplements, and information on authorship & disclosures: www.haematologica.org/content/104/11/2144

References

- 1.Eichhorst B, Fink AM, Bahlo J, et al. First-line chemoimmunotherapy with bendamustine and rituximab versus fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, and rituximab in patients with advanced chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (CLL10): an international, open-label, randomised, phase 3, non-inferiority trial. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17(7):928–942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hallek M, Fischer K, Fingerle-Rowson G, et al. Addition of rituximab to fludarabine and cyclophosphamide in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukaemia: a randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2010;376(9747):1164–1174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burger JA, Tedeschi A, Barr PM, et al. Ibrutinib as initial therapy for patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(25):2425–2437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Furman RR, Sharman JP, Coutre SE, et al. Idelalisib and rituximab in relapsed chronic lymphocytic leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(11):997–1007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hallek M, Cheson BD, Catovsky D, et al. iwCLL guidelines for diagnosis, indications for treatment, response assessment, and supportive management of CLL. Blood. 2018;131(25):2745–2760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hallek M, Shanafelt TD, Eichhorst B. Chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Lancet. 2018;391(10129):1524–1537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Roberts AW, Davids MS, Pagel JM, et al. Targeting BCL2 with venetoclax in relapsed chronic lymphocytic leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(4):311–322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moreno C, Greil R, Demirkan F, et al. Ibrutinib plus obinutuzumab versus chlorambucil plus obinutuzumab in first-line treatment of chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (iLLUMINATE): a multicentre, randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2019;20(1):43–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shanafelt TD, Wang XV, Kay NE, et al. Ibrutinib-rituximab or chemoimmunotherapy for chronic lymphocytic leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2019. Aug 1;381(5):432–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Woyach JA, Ruppert AS, Heerema NA, et al. Ibrutinib regimens versus chemoimmunotherapy in older patients with untreated CLL. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(26):2517–2528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fischer K, Bahlo J, Fink AM, et al. Long-term remissions after FCR chemoimmunotherapy in previously untreated patients with CLL: updated results of the CLL8 trial. Blood. 2016;127(2):208–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thompson PA, Tam CS, O’Brien SM, et al. Fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, and rituximab treatment achieves long-term disease-free survival in IGHV-mutated chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2016;127(3):303–309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Byrd JC, Brown JR, O’Brien S, et al. Ibrutinib versus ofatumumab in previously treated chronic lymphoid leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(3):213–223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Byrd JC, Furman RR, Coutre SE, et al. Targeting BTK with ibrutinib in relapsed chronic lymphocytic leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(1):32–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barr PM, Robak T, Owen C, et al. Sustained efficacy and detailed clinical follow-up of first-line ibrutinib treatment in older patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia: extended phase 3 results from RESONATE-2. Haematologica. 2018;103(9):1502–1510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ahn IE, Farooqui MZH, Tian X, et al. Depth and durability of response to ibrutinib in CLL: 5-year follow-up of a phase 2 study. Blood. 2018;131(21):2357–2366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ahn IE, Tian X, Albitar M, et al. Validation of clinical prognostic models and integration of genetic biomarkers of drug resistance in CLL patients treated with ibrutinib. Blood. 2018;132(Suppl 1):186. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Quinquenel A, Fornecker LM, Letestu R, et al. High Prevalence of BTK Mutations on ibrutinib therapy after 3 years of treatment in a real-life cohort of CLL patients: a study from the French Innovative Leukemia Organization (FILO) Group. Blood. 2018; 132(Suppl 1):584. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mato AR, Nabhan C, Thompson MC, et al. Toxicities and outcomes of 616 ibrutinib-treated patients in the United States: a real-world analysis. Haematologica. 2018;103(5): 874–879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brown JR, Moslehi J, O’Brien S, et al. Characterization of atrial fibrillation adverse events reported in ibrutinib randomized controlled registration trials. Haematologica. 2017;102(10):1796–1805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Byrd JC, Harrington B, O’Brien S, et al. Acalabrutinib (ACP-196) in relapsed chronic lymphocytic leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(4):323–332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tam C. Pooled analysis of safety data from zanubrutinib (BGB-3111) monotherapy studies in hematologic malignancies. EHA Annual Meeting 2018;214907. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Byrd JC, Smith S, Wagner-Johnston N, et al. First-in-human phase 1 study of the BTK inhibitor GDC-0853 in relapsed or refractory B-cell NHL and CLL. Oncotarget. 2018;9(16):13023–13035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Reiff SD, Mantel R, Smith LL, et al. The BTK inhibitor ARQ 531 targets ibrutinib-resistant CLL and Richter transformation. Cancer Discov. 2018;8(10):1300–1315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brown JR, Byrd JC, Coutre SE, et al. Idelalisib, an inhibitor of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase p110delta, for relapsed/refractory chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2014;123(22):3390–3397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.O’Brien SM, Lamanna N, Kipps TJ, et al. A phase 2 study of idelalisib plus rituximab in treatment-naive older patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2015;126(25): 2686–2694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lampson BL, Kasar SN, Matos TR, et al. Idelalisib given front-line for treatment of chronic lymphocytic leukemia causes frequent immune-mediated hepatotoxicity. Blood. 2016;128(2):195–203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.European Medicines Agency EMA reviews cancer medicine Zydelig. https://wwwe-maeuropaeu/en/news/ema-reviews-cancer-medicine-zydelig 2016. (accessed: 11/02/2019). 2016.

- 29.Flinn IW, Hillmen P, Montillo M, et al. The phase 3 DUO trial: duvelisib vs ofatumumab in relapsed and refractory CLL/SLL. Blood. 2018;132(23):2446–2455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Burris HA, 3rd, Flinn IW, Patel MR, et al. Umbralisib, a novel PI3Kdelta and casein kinase-1epsilon inhibitor, in relapsed or refractory chronic lymphocytic leukaemia and lymphoma: an open-label, phase 1, dose-escalation, first-in-human study. Lancet Oncol. 2018;19(4):486–496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Seymour JF, Kipps TJ, Eichhorst B, et al. Venetoclax-rituximab in relapsed or refractory chronic lymphocytic leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(12):1107–1120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stilgenbauer S, Eichhorst B, Schetelig J, et al. Venetoclax for patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia with 17p deletion: results from the full population of a phase II pivotal trial. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(19):1973–1980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wierda WG, Roberts AW, Ghia P, et al. Minimal residual disease status with venetoclax monotherapy is associated with progression-free survival in chronic lymphocytic Leukemia. Blood. 2018;132(Suppl 1): 3134. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dimier N, Delmar P, Ward C, et al. A model for predicting effect of treatment on progression-free survival using MRD as a surrogate end point in CLL. Blood. 2018;131(9):955–962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kater AP, Seymour JF, Hillmen P, et al. Fixed duration of venetoclax-rituximab in relapsed/refractory chronic lymphocytic leukemia eradicates minimal residual disease and prolongs survival: post-treatment follow-up of the MURANO phase III study. J Clin Oncol. 2019;37(4):269–277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Davids MS, Hallek M, Wierda W, et al. Comprehensive safety analysis of venetoclax monotherapy for patients with relapsed/refractory chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Clin Cancer Res. 2018;24(18): 4371–4379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Blombery P, Anderson MA, Gong JN, et al. Acquisition of the recurrent Gly101Val mutation in BCL2 confers resistance to venetoclax in patients with progressive chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Cancer Discov. 2019;9(3):342–353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Herling CD, Abedpour N, Weiss J, et al. Clonal dynamics towards the development of venetoclax resistance in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Nat Commun. 2018;9(1):727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mato AR, Hill BT, Lamanna N, et al. Optimal sequencing of ibrutinib, idelalisib, and venetoclax in chronic lymphocytic leukemia: results from a multicenter study of 683 patients. Ann Oncol. 2017;28(5):1050–1056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jones JA, Mato AR, Wierda WG, et al. Venetoclax for chronic lymphocytic leukaemia progressing after ibrutinib: an interim analysis of a multicentre, open-label, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2018;19(1):65–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mato AR, Tam CS, Allan JN, et al. Disease and patient characteristics, patterns of care, toxicities, and outcomes of chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) patients treated with venetoclax: a multicenter study of 204 patients. Blood. 2017;130(Suppl 1):4315. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Greil R, Fraser G, Leber B, et al. Efficacy and safety of ibrutinib (IBR) after venetoclax (VEN) treatment in IBR-naïve patients with relapsed/refractory (R/R) chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL): follow-up of patients from the MURANO study. Blood. 2018; 132(Suppl 1):5548. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Awan FT, Schuh A, Brown JR, et al. Acalabrutinib monotherapy in patients with ibrutinib intolerance: results from the phase 1/2 ACE-CL-001 clinical study. Blood. 2016;128(22): 638.27301860 [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mato AR, Schuster SJ, Lamanna N, et al. A phase 2 study to assess the safety and efficacy of umbralisib (TGR-1202) in pts with CLL who are intolerant to prior BTK or PI3Kδ inhibitor therapy. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(15_suppl):7530. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Barr PM, Brown JR, Hillmen P, et al. Impact of ibrutinib dose adherence on therapeutic efficacy in patients with previously treated CLL/SLL. Blood. 2017;129(19):2612–2615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ahn IE, Underbayev C, Albitar A, et al. Clonal evolution leading to ibrutinib resistance in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2017;129(11):1469–1479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Woyach JA, Ruppert AS, Guinn D, et al. BTK(C481S)-mediated resistance to ibrutinib in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(13):1437–1443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Byrd JC, Hillmen P, O’Brien S, et al. Long-term follow-up of the RESONATE™ phase 3 trial of ibrutinib versus ofatumumab. Blood. 2019;133(19):2031–2042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chen Q, Jain N, Ayer T, et al. Economic Burden of chronic lymphocytic leukemia in the era of oral targeted therapies in the United States. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(2):166–174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Spina V, Forestieri G, Zucchetto A, et al. Mechanisms of adaptation to ibrutinib in high risk chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2018;132(Suppl 1):585. [Google Scholar]

- 51.EMA. (European Medicines Agency) Appendix 4 to the guideline on the evaluation of anticancer medicinal products in man condition specific guidance. https://wwwemaeuropaeu/en/appendix-4-guideline-evaluation-anticancer-medicinal-products-man-condition-specific-guidance 2016.

- 52.Bottcher S, Ritgen M, Fischer K, et al. Minimal residual disease quantification is an independent predictor of progression-free and overall survival in chronic lymphocytic leukemia: a multivariate analysis from the randomized GCLLSG CLL8 trial. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(9):980–988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Goede V, Fischer K, Busch R, et al. Obinutuzumab plus chlorambucil in patients with CLL and coexisting conditions. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(12):1101–1110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kovacs G, Robrecht S, Fink AM, et al. Minimal residual disease assessment improves prediction of outcome in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) who achieve partial response: comprehensive analysis of two phase III studies of the German CLL Study Group. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(31):3758–3765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Langerak AW, Ritgen M, Goede V, et al. Prognostic value of MRD in CLL patients with comorbidities receiving chlorambucil plus obinutuzumab or rituximab. Blood. 2019;133(5):494–497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chanan-Khan A, Cramer P, Demirkan F, et al. Ibrutinib combined with bendamustine and rituximab compared with placebo, ben-damustine, and rituximab for previously treated chronic lymphocytic leukaemia or small lymphocytic lymphoma (HELIOS): a randomised, double-blind, phase 3 study. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17(2):200–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Fraser G, Cramer P, Demirkan F, et al. Updated results from the phase 3 HELIOS study of ibrutinib, bendamustine, and rituximab in relapsed chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphocytic lymphoma. Leukemia. 2019;33(4):969–980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zelenetz AD, Barrientos JC, Brown JR, et al. Idelalisib or placebo in combination with bendamustine and rituximab in patients with relapsed or refractory chronic lymphocytic leukaemia: interim results from a phase 3, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18(3):297–311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Davids MS, Brander DM, Kim HT, et al. Ibrutinib plus fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, and rituximab as initial treatment for younger patients with chronic lymphocytic leukaemia: a single-arm, multicentre, phase 2 trial. Lancet Haematol. 2019; 6(8):e419–e28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Jain N, Thompson PA, Burger JA, et al. Ibrutinib, fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, and obinutuzumab (iFCG) for firstline treatment of patients with CLL with mutated IGHV and without TP53 aberrations. Blood. 2018;132(Suppl 1):695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Michallet A-S, Dilhuydy M-S, Subtil F, et al. High rate of complete response (CR) with undetectable bone marrow minimal residual disease (MRD) after chemo-sparing and MRD-driven strategy for untreated fit CLL patients: final results of the Icll 07 FILO trial. Blood. 2018;132(Suppl 1):1858. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Davids MS. A Phase Ib/II study of duvelisib in combination with FCR (dFCR) for front-line therapy of younger CLL patients. EHA Annual Meeting; oral presentation 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Burger JA, Sivina M, Jain N, et al. Randomized trial of ibrutinib versus ibrutinib plus rituximab in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2019; 133(10):1011–1019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Woyach JA, Awan FT, Jianfar M, et al. Acalabrutinib with obinutuzumab in relapsed/refractory and treatment-naive patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia: the phase 1b/2 ACE-CL-003 study. Blood. 2017;130(Suppl 1):432. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Cramer P, von Tresckow J, Robrecht S, et al. Bendamustine followed by ofatumumab and ibrutinib in patients with chronic lym-phocytic leukemia (CLL): CLL2-BIO trial of the German CLL Study Group (GCLLSG). Blood. 2017;130(Suppl 1):494. [Google Scholar]

- 66.von Tresckow J, Cramer P, Bahlo J, et al. CLL2-BIG: sequential treatment with bendamustine, ibrutinib and obinutuzumab (GA101) in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Leukemia. 2019;33(5):1161–1172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Cramer P, von Tresckow J, Bahlo J, et al. Bendamustine followed by obinutuzumab and venetoclax in chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (CLL2-BAG): primary endpoint analysis of a multicentre, open-label, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2018;19(9):1215–1228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Cramer P, von Tresckow J, Bahlo J, et al. Durable remissions after discontinuation of combined targeted treatment in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) harbouring a high-risk genetic lesion (del(17p)/TP53 mutation). Blood. 2018;132(Suppl 1):694.29907599 [Google Scholar]

- 69.Fischer K, Al-Sawaf O, Bahlo J, et al. Venetoclax and Obinutuzumab in Patients with CLL and Coexisting Conditions. The N Engl J Med. 2019;380(23):2225–2236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Flinn IW, Gribben JG, Dyer MJS, et al. Phase 1b study of venetoclax-obinutuzumab in previously untreated and relapsed/refractory chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2019. March 12 [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Hillmen P, Rawstron A, Brock K, et al. Ibrutinib plus venetoclax in relapsed/refractory CLL: results of the Bloodwise TAP Clarity Study. Blood. 2018;132(Suppl 1):182. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Jain N, Keating M, Thompson P, et al. Ibrutinib and Venetoclax for First-Line Treatment of CLL. N Engl J Med. 2019; 380(22):2095–2103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Rogers KA, Huang Y, Ruppert AS, et al. Phase 2 study of combination obinutuzumab, ibrutinib, and venetoclax in treatment-naive and relapsed/refractory chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2018;132(Suppl 1):693. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Davids MS, Kim HT, Nicotra A, et al. Umbralisib in combination with ibrutinib in patients with relapsed or refractory chronic lymphocytic leukaemia or mantle cell lymphoma: a multicentre phase 1-1b study. Lancet Haematol. 2019;6(1):e38–e47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Nastoupil LJ, Lunning MA, Vose JM, et al. Tolerability and activity of ublituximab, umbralisib, and ibrutinib in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukaemia and non-Hodgkin lymphoma: a phase 1 dose escalation and expansion trial. Lancet Haematol. 2019;6(2):e100–e109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ding W, LaPlant BR, Call TG, et al. Pembrolizumab in patients with CLL and Richter transformation or with relapsed CLL. Blood. 2017;129(26):3419–3427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Younes A, Brody J, Carpio C, et al. Safety and activity of ibrutinib in combination with nivolumab in patients with relapsed non-Hodgkin lymphoma or chronic lymphocytic leukaemia: a phase 1/2a study. Lancet Haematol. 2019;6(2):e67–e78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Mato AR, Thompson M, Allan JN, et al. Real-world outcomes and management strategies for venetoclax-treated chronic lymphocytic leukemia patients in the United States. Haematologica. 2018;103(9):1511–1517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Chen Q, Jain N, Ayer T, et al. Economic burden of chronic lymphocytic leukemia in the era of oral targeted therapies in the United States. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(2):166–174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Kadri S, Lee J, Fitzpatrick C, et al. Clonal evolution underlying leukemia progression and Richter transformation in patients with ibrutinib-relapsed CLL. Blood Adv. 2017;1(12):715–727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Landau DA, Sun C, Rosebrock D, et al. The evolutionary landscape of chronic lymphocytic leukemia treated with ibrutinib targeted therapy. Nat Commun. 2017;8(1):2185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Lampson BL, Yu L, Glynn RJ, et al. Ventricular arrhythmias and sudden death in patients taking ibrutinib. Blood. 2017;129(18):2581–2584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Ghez D, Calleja A, Protin C, et al. Early-onset invasive aspergillosis and other fungal infections in patients treated with ibrutinib. Blood. 2018;131(17):1955–1959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Bercusson A, Colley T, Shah A, Warris A, Armstrong-James D. Ibrutinib blocks Btk-dependent NF-kB and NFAT responses in human macrophages during Aspergillus fumigatus phagocytosis. Blood. 2018;132(18):1985–1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Waldron M, Winter A, Hill BT. Pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic considerations in the treatment of chronic lymphocytic leukemia: ibrutinib, idelalisib, and venetoclax. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2017;56(11):1255–1266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Baliakas P, Jeromin S, Iskas M, et al. Cytogenetic complexity in chronic lymphocytic leukemia: definitions, associations and clinical impact. Blood. 2019;133(11):1205–1216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Visentin A, Deodato M, Mauro FR, et al. A Scoring system to predict the risk of atrial fibrillation in chronic lymphocytic leukemia and its validation in a cohort of ibrutinib-treated patients. Blood. 2018;132(Suppl 1):3118. [Google Scholar]