Washing machines should be further investigated as possible sites for horizontal gene transfer (ESBL genes) and cross-contamination with clinically important Gram-negative strains. Particularly in the health care sector, the knowledge of possible (re-)contamination of laundry (patients’ clothes and staff uniforms) with multidrug-resistant Gram-negative bacteria could help to prevent and to control nosocomial infections. This report describes an outbreak with a single strain of a multidrug-resistant bacterium (Klebsiella oxytoca sequence type 201) in a neonatal intensive care unit that was terminated only when the washing machine was removed. In addition, the study implies that changes in washing machine design and processing are required to prevent accumulation of residual water where microbial growth can occur and contaminate clothes.

KEYWORDS: ESBL-producing bacteria, Klebsiella oxytoca, ST201, washing machine, laundry, colonization, newborns

ABSTRACT

During the period from April 2012 to May 2013, 13 newborns (1 to 4 weeks of age) and 1 child in a pediatric hospital ward in Germany were colonized with Klebsiella oxytoca producing an extended-spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL) (CTX-M-15). A microbiological source-tracking analysis with human and environmental samples was carried out to identify the source and transmission pathways of the K. oxytoca clone. In addition, different hygienic intervention methods were evaluated. K. oxytoca isolates were detected in the detergent drawer and on the rubber door seal of a domestic washer-extractor machine that was used in the same ward to wash laundry for the newborns, as well as in two sinks. These strains were typed using pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) and multilocus sequence typing. The environmental findings were compared with those for the human strains and the isolates detected on clothing. The results from both techniques showed that the strains were identical (sequence type 201 and PFGE type 00531, a clone specific to this hospital and not previously isolated in Germany), emphasizing the washing machine as a reservoir and fomite for the transmission of these multidrug-resistant bacteria. After the washing machine was taken out of use, no further colonizations were detected during the subsequent 4-year period.

IMPORTANCE Washing machines should be further investigated as possible sites for horizontal gene transfer (ESBL genes) and cross-contamination with clinically important Gram-negative strains. Particularly in the health care sector, the knowledge of possible (re-)contamination of laundry (patients’ clothes and staff uniforms) with multidrug-resistant Gram-negative bacteria could help to prevent and to control nosocomial infections. This report describes an outbreak with a single strain of a multidrug-resistant bacterium (Klebsiella oxytoca sequence type 201) in a neonatal intensive care unit that was terminated only when the washing machine was removed. In addition, the study implies that changes in washing machine design and processing are required to prevent accumulation of residual water where microbial growth can occur and contaminate clothes.

INTRODUCTION

Water or wastewater contaminated with facultative pathogenic microorganisms provides a potential reservoir for infections (1–3). The most common bacteria causing health care-associated infections or permanently colonizing reservoirs linked to contaminated hospital water in the environments of patients are Gram-negative bacteria, including Pseudomonas spp., Enterobacter spp., Serratia spp., Stenotrophomonas spp., and Klebsiella spp. (1, 2, 4). Such water reservoirs in health care settings include faucets, sink surfaces, bathtubs, wastewater drainage system drains, sinks, showers, and toilets (4, 5). Persisting and especially multidrug-resistant (MDR) bacteria in those reservoirs pose severe risks, especially for high-risk patients such as severely immunocompromised patients, newborns (1 to 4 weeks of age), and infants (6 to 8 weeks of age) in neonatal intensive care units (ICUs) (4, 6–10). For example, Leitner et al. (11) described an outbreak of 6 infections in patients with hematological malignancies that involved a strain of KPC-2-producing Klebsiella oxytoca, which is most commonly linked to contaminated water reservoirs. Identification of the contaminated environmental reservoir in such outbreaks can be challenging, and transmission pathways have been elucidated in only a few clinical studies (6, 12, 13).

Currently, washing machines and clothing are not assessed as potential reservoirs in outbreaks of nosocomial infections, despite evidence that a potential health risk due to contaminated laundry cannot be excluded (14–16). Recently, Rehberg et al. (17) described the presence of antibiotic-resistant bacteria (ARB) and their possible transmission via washing machines.

RESULTS

Case description.

Between April 2012 and May 2013, increased rates of colonization with K. oxytoca isolates were recorded in a level 1 perinatal center (PNC) and in several wards in the connected children’s hospital (90 stationary beds and 20 ICU beds) in western Germany. The colonizations had been noticed after implementation of a standard screening procedure for incoming individuals and/or patients with risk factors (newborns, children, and mothers), as a general control mechanism aimed at reducing the spread of MDR bacteria. Screening included anal swabs (newborns, children, and mothers), vaginal swabs (mothers), and in some cases additional wound swabs (newborns and children).

Colonization with K. oxytoca in humans.

Within 14 months, 27 children were colonized (but not infected) with K. oxytoca, according to CDC definitions (18). The occurrence of K. oxytoca varied from sensitive isolates with no extended-spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL) activity to ESBL-producing K. oxytoca isolates and the particular ESBL-producing K. oxytoca pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) type 00531. Fourteen children tested positive for PFGE type 00531 ESBL-producing K. oxytoca.

K. oxytoca was mostly identified in rectal swab screening samples. For 9 of 24 newborns, K. oxytoca was also detected in throat swab samples. As an exception, a 4-year-old boy in the ICU who never had any direct contact with the PNC also showed rectal colonization with PFGE type 00531/sequence type 201 (ST201) ESBL-producing K. oxytoca in March 2013.

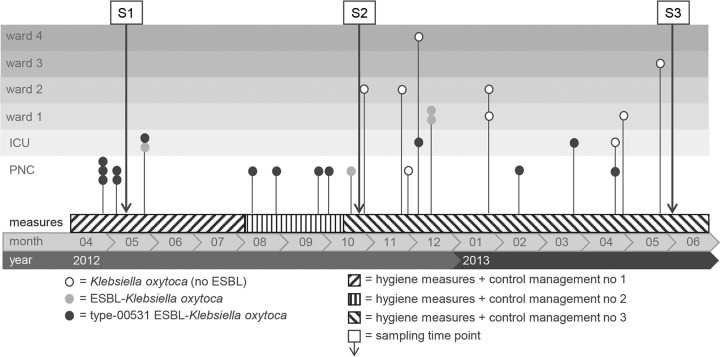

All ESBL-producing K. oxytoca strains were resistant to piperacillin-tazobactam (MICs up to and higher than the measurable limit of 64/4 mg/liter), cefotaxime (MICs of ≥64 mg/liter), ceftazidime (MICs of >128 mg/liter), and ciprofloxacin (MICs of ≥2 mg/liter) and could be classified as MDR according to the guidelines reported by Magiorakos et al. (19). Figure 1 summarizes the occurrence of K. oxytoca isolates over time in the PNC, the ICU, and four different wards.

FIG 1.

Course of the outbreak with different K. oxytoca strains over 1 year and their distributions in different wards. S1, first sampling; S2, second sampling; S3, third sampling.

Until October 2012, only newborns in the PNC or infants in the ICU were colonized with ESBL-producing K. oxytoca, some strains of which belonged to PFGE type 00531/ST201 (Fig. 1). From the end of October 2012 to February 2013, K. oxytoca was also detected on other wards and among older pediatric patients (see above).

During an extended screening of mothers and health care workers (HCWs), a total of 695 swabs (vaginal and rectal) from 428 persons were obtained on the obstetrics ward. The screening identified 4 mothers colonized with K. oxytoca, 5 mothers colonized with ESBL-producing Escherichia coli, and 1 mother colonized with ESBL-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae. None was positive for PFGE type 00531 ESBL-producing K. oxytoca. Transmission between a mother and a newborn was not documented.

Environmental monitoring.

All environmental samples obtained during the first and second on-site inspections tested negative for Enterobacterales and nonfermenting organisms. During the second on-site sampling, in October 2012, only low concentrations of Gram-positive skin and environmental bacteria were present. During the third on-site inspection, in June 2013, sampling was conducted using native samples (drinking water and wastewater) and liquid medium swabs (ESwabs). Thus, Enterobacterales and nonfermenting bacteria were detected. All K. oxytoca isolates were identical ESBL-producing strains and belonged to PFGE type 00531 (Table 1). In the following discussion, these K. oxytoca strains are termed environmental.

TABLE 1.

Occurrence of Gram-negative Enterobacterales strains, nonfermenting organisms, and PFGE type 00531 ESBL-producing K. oxytoca isolates in environmental samples obtained during on-site inspection of risk areas

| Room | Sampling point | Counts (CFU/ml or total Gram-negative bacterial count) | Microbiological differentiation | CTX-M | PFGE type 00531/ST201 K. oxytoca |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nursing care room, storage rooms | Working basin, siphon | 2.1 × 105 | Serratia marcescens | ||

| Hand wash basin, siphon water | 1.6 × 106 | K. oxytoca | Positive | Yes | |

| Raoultella terrigena | Negative | ||||

| Enterobacter cloacae complex | Negative | ||||

| Hand wash basin, drainage hole cover | Scattered/swab (no CFU/ml) | E. cloacae complex | Negative | ||

| K. pneumoniae | Negative | ||||

| Staff toilet | Hand wash basin, fresh water | Not evaluable/100 ml | Gram-negative nonfermenting rods | ||

| Hand wash basin, siphon water | 1.5 × 104 | P. aeruginosa, S. maltophilia | |||

| Toilet, water | 1.0 | S. maltophilia | |||

| Staff room | Kitchen sink, siphon water | 3.0 × 105 | K. oxytoca | Positive | Yes |

| P. aeruginosa | Negative | ||||

| Water reservoir tank, espresso machine | 10.0 CFU/50 ml | S. maltophilia | |||

| Hygiene sluice, PNC | Hand wash basin, siphon water | 1.3 × 104 | P. aeruginosa, Gram-negative nonfermenting rods | ||

| Basement, laundry room | Tumble dryer, water tray | Not evaluable/50 ml | Gram-negative nonfermenting rods | ||

| Washing machine 1, residual water, rubber mantle | 3.9 × 102 | K. oxytoca | Positive | Yes | |

| Washing machine 1, detergent compartment | Not evaluable/swab | K. oxytoca | Positive | Yes | |

| P. aeruginosa | Negative | ||||

| Washing machine 2, detergent compartment | Not evaluable/swab | P. aeruginosa | |||

| Laundry | Hat 1 | >109 | K. oxytoca | Positive | Yes |

| Hat 2 | >109 | K. oxytoca | Positive | Yes | |

| Hat 3 | >109 | K. oxytoca | Positive | Yes | |

| Hat 4 | >109 | K. oxytoca | Positive | Yes | |

| Socks 1 | >109 | K. oxytoca | Positive | Yes | |

| Socks 2 | >109 | K. oxytoca | Positive | Yes |

Water-associated bacteria, such as Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Serratia spp., Enterobacter spp., K. pneumoniae, and Stenotrophomonas maltophilia, were detected in the siphons of hand wash basins. Identical clones of PFGE type 00531/ST201 K. oxytoca were isolated from the siphons of two sinks in the HCW staff room and in the room used for cleaning and disinfection. The same clone was also isolated at high concentrations from samples of residual water in the rubber seal and from a swab sample (in addition to P. aeruginosa) from the detergent compartment of one of the two washing machines (Table 1) located on the ground floor of the same ward.

Following identification of the washing machine as a potential reservoir for this specific K. oxytoca clone, newborn clothing (hats and socks) that had been washed in this machine were microbiologically analyzed. PFGE type 00531/ST201 K. oxytoca of the same specific clone was isolated, with total counts of >109 CFU/ml. All PFGE type 00531/ST201 ESBL-producing K. oxytoca isolates found in the residual water and environmental samples were also resistant to piperacillin-tazobactam (MICs ranging from 8/4 mg/liter to >64/4 mg/liter), cefotaxime (MICs of >2 mg/liter), ceftazidime (MICs of 64 mg/liter), and ciprofloxacin (MICs of ≥ 2 mg/liter) (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

MICs of K. oxytoca isolates obtained during on-site inspection of risk areas

| No. | Species | Sample type | MIC (mg/liter)a |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Piperacillin | Piperacillin-tazobactam | Cefotaxime | Ceftazidime | Imipenem | Meropenem | Amikacin | Ciprofloxacin | |||

| 1 | K. oxytoca | Washing machine | R (>16) | I (16/4) | R (>2) | R (32) | S (≤1) | S (≤0.125) | S (≤4) | R (2) |

| 2 | K. oxytoca | Washing machine | R (>16) | R (>64/4) | R (>2) | R (32) | S (≤1) | S (≤0.125) | S (8) | R (2) |

| 3 | K. oxytoca | Washing machine | R (>16) | R (64/4) | R (>2) | R (32) | S (≤1) | S (≤0.125) | S (8) | R (2) |

| 4 | K. oxytoca | Siphon from wash basin in staff lobby | R (>16) | R (32/4) | R (>2) | R (32) | S (≤1) | S (≤0.125) | S (8) | R (>2) |

| 5 | K. oxytoca | Siphon from wash basin in staff lobby | R (>16) | S (8/4) | R (>2) | R (32) | S (≤1) | S (≤0.125) | S (≤4) | R (2) |

| 6 | K. oxytoca | Siphon from wash basin in staff lobby | R (>16) | I (16/4) | R (>2) | R (64) | S (≤1) | S (≤0.125) | S (≤4) | R (2) |

| 7 | K. oxytoca | Human | R (>16) | R (>64/4) | R (>2) | R (>128) | S (≤1) | S (≤0.125) | I (16) | R (>2) |

| 8 | K. oxytoca | Human | R (>16) | R (>64/4) | R (>2) | R (>128) | S (≤1) | S (≤0.125) | S (8) | R (>2) |

| 9 | K. oxytoca | Human | R (>16) | R (>64/4) | R (>2) | R (>128) | S (≤1) | S (≤0.125) | S (8) | R (>2) |

| 10 | K. oxytoca | Human | R (>16) | R (>64/4) | R (>2) | R (>128) | S (≤1) | S (≤0.125) | S (≤4) | R (>2) |

| 11 | K. oxytoca | Human | R (>16) | R (>64/4) | R (>2) | R (>128) | S (≤1) | S (≤0.125) | S (8) | R (>2) |

| 12 | K. oxytoca | Human | R (>16) | R (>64/4) | R (>2) | R (>128) | S (≤1) | S (≤0.125) | S (≤4) | R (>2) |

| 13 | K. oxytoca | Human | R (>16) | R (>64/4) | R (>2) | R (>128) | S (≤1) | S (≤0.125) | S (≤4) | R (2) |

| 14 | K. oxytoca | Human | R (>16) | R (>64/4) | R (>2) | R (>128) | S (≤1) | S (≤0.125) | S (≤4) | R (>2) |

| 15 | K. oxytoca | Human | R (>16) | R (>64/4) | R (>2) | R (>128) | S (≤1) | S (≤0.125) | S (8) | R (>2) |

| 16 | K. oxytoca | Human | R (>16) | R (>64/4) | R (>2) | R (>128) | S (≤1) | S (≤0.125) | S (≤4) | R (>2) |

R, resistant; I, intermediate; S, sensitive.

The presence of the CTX-M-15 ESBL gene in all human and environmental strains was confirmed by sequencing. The transfer of putative plasmids harboring these genes under laboratory conditions into wild-type E. coli strains via conjugation was not successful. In addition, no amplicons for inc genes (incA/C, incL, incHI2, incM, incI1-αγ, incN, incFIIk, incFIA, incFIB, and incFII) were obtained from the strains, indicating that the CTX-M genes might be chromosomally located, as described by Rodríguez et al. (20).

Epidemiological links.

Retrospective analysis demonstrated that only newborns who had worn clothing that had been washed in the in-house washing machine were colonized with the redundant K. oxytoca clone. Although the siphons of the staff sinks were also identified as a possible reservoir, no staff members were identified as carriers or spreaders of ESBL-producing Enterobacterales at the time of screening.

All clinical and environmental isolates of PFGE type 00531/ST201 K. oxytoca displayed identical PFGE banding patterns and thus were considered clonally identical. This clone was specific for the newborns/infants and some environmental samples.

Evaluation of possibly increased disinfectant tolerance of the K. oxytoca strains.

The environmental K. oxytoca isolates showed no increased tolerance to the surface disinfectant based on quaternary ammonium compounds and alkylamine. The alkylamine MICs for the K. oxytoca strains were identified as up to a maximum of 0.003%, compared to 0.0075% for the Pseudomonas aeruginosa reference strain. Furthermore, the examination according to Verbund für Angewandte Hygiene e.V. (VAH) method 9 showed reductions in the K. oxytoca strains of ≥5 log10 CFU at a concentration of 0.5% for 15 min in the presence of interfering substances (3.0 g/liter bovine serum albumin plus 3.0 ml/liter sheep erythrocytes [i.e., dirty conditions]). The VAH-recommended concentration and application time are 0.5% for 60 min (https://vah-online.de/en/for-users).

K. oxytoca isolates from the environment showed no increased tolerance to the laundry disinfectant based on peracetic acid. The MICs of the K. oxytoca strains and the P. aeruginosa reference strain were identified as 5 g/liter. The analysis according to VAH method 9 (in the presence of 2.75 g/liter laundry disinfectant with an exposure time of 15 min, under dirty conditions, at 20°C, 40°C, and 60°C) demonstrated that the K. oxytoca strains were more susceptible than the Gram-negative reference strain P. aeruginosa DSM 939. At a temperature of 60°C, all K. oxytoca strains showed reductions of ≥5 log10 units.

Hygienic containment measures and control management strategies.

A task force was formed to manage the control interventions for prevention of the colonization of additional patients and to identify possible sources of the suspected K. oxytoca strain. The management procedures were divided into three main phases, until the colonizations were under control and the source could finally be identified. In each phase, step-by-step approaches with different strategies were necessary, in parallel with sampling during the whole reporting period (Fig. 1 and Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Hygienic measures and control management procedures

| Time period | Procedure(s) |

|---|---|

| April to August 2012 | Environmental monitoring, including sampling of siphons, sinks, and showers via contact plates |

| Continuation of admission screening and weekly routine screening and implementation of second newborn screening (48 h postpartum) | |

| Screening of all mothers at admission and at discharge | |

| Monitoring of pathways of newborns from birth to admission in the PNC | |

| Maintenance of incubator isolation until two-time negative screening results | |

| Advanced training of HCWs, with special focus on toilet and hand hygiene | |

| Microbiological analyses of vaginal ultrasound probes and heated towels used for primary care of newborns | |

| Renovation/decontamination of ward rooms and removal of unused sinks | |

| Installation of new wall-mounted disinfection dispensers | |

| Screening of clinical procedures for any cross-contamination possibilities | |

| Feeding of newborns with only precooked single-serving packages | |

| Use of sterile water for bathing of newborns | |

| August to October 2012 | Screening of all HCWs working in the PNC, ICU, or obstetrics department |

| October 2012 to June 2013 | Extended environmental sampling from different areas in the ward and functionally linked areas in the hospital, with identification and sampling of specific risk factors (e.g., washing machine) |

| Training of staff in correct handling of disinfectant wipes | |

| Training of HCWs in correct disinfection and cleaning of incubators | |

| Preparation of disinfectant wipes with newly validated/approved preparation machine | |

| Construction measures to provide work space for hygienic processing of incubators and to ensure sufficient storage capacities | |

| Marking of all thermometers (rectal and commercially available thermometers) and incubators for traceability | |

| Intensive audit of all procedures used in the ward during routine operations |

Long-term clinical effects and concomitant infection control interventions.

After the washing machine had been taken out of use, no further colonization of newborns with K. oxytoca has been detected to this day. All garments worn by newborns and children were laundered by a professional external hospital laundry service after the outbreak. The two colonized sinks were replaced by sinks with specialized thermosiphon systems. As a further consequence of the prolonged cluster process, the existing infection control measures (isolating colonized patients, enforcing hand hygiene measures, and cleaning the ward, particularly the sinks and equipment) were reinforced via extra training. The screening plan for all newborns and children and all measures implemented within the containment program continue to be maintained.

DISCUSSION

Reservoirs and transmission routes for waterborne pathogens in health care systems.

When the first 5 cases of colonization with K. oxytoca were detected, between August and October 2012, person-to-person transmission was suggested. Although this has not been reported for K. oxytoca, Price et al. (21) showed that, in the presence of standard infection control measures, HCWs were frequent sources of Staphylococcus aureus transmission. Furthermore, Heudorf et al. (22) mentioned that pathogens classified by the World Health Organization as highest priority can be found on staff gowns, which can be the starting point for transmissions (23).

In this case, the occurrence of K. oxytoca isolates continued over a 1-year period, which indicated a reservoir in the environment rather than among hospital personnel or mothers. Despite the strict implementation of control management and containment measures, newborns and children continued to acquire the cluster organism (PFGE type 00531/ST201), which had never been detected previously by the German National Reference Centre (GNRC). The single database strain was isolated in the Netherlands in 2018 (24).

Washing machine.

In this case, the particular K. oxytoca strain was detected not only in two sinks but also in a domestic washing machine with an integrated dryer. Even recently published articles reviewing the main water-associated reservoirs in hospitals do not consider washing machines as potential hazards in clinical environments (4, 5). In our case, however, the knitted clothes of patients were washed in an in-house washing machine designed for household use and enabling a washing temperature of 65°C. It has been shown that resistance genes, as well as different microorganisms, can persist in domestic washing machines (17, 25).

Recently, a study suggested the potential role of washing machines in the distribution of antibiotic-resistant Gram-negative bacteria during laundering (17); until now, however, no transmission of pathogens from a washing machine to patients could be proven. In this case, we assume that the PFGE type 00531/ST201 K. oxytoca strain was disseminated to clothing after the washing process, via residual water on the rubber mantle and/or via the final rinsing process, which ran unheated and detergent-free water through the detergent compartment, although the water coming to the washing machine met the quality requirements of the hospital’s internal water controls. Consequently, we concluded that newborns were colonized by wearing hats and socks that had been contaminated by the washing process.

It remains unclear how the washing machine was contaminated. However, Enterobacterales species can survive in wet environments for extended periods (1), especially waterborne bacteria such as P. aeruginosa and Klebsiella strains, which have the ability to survive in a viable but nonculturable state. Their environmental stability is supported by the formation of biofilms to enhance their chances of multiplication and horizontal gene transfer (26). Zhang et al. (27) reported that biofilm detachment is promoted by disinfectants, thus affecting the overall antibiotic resistance of microbes in tap water.

Furthermore, Rehberg et al. (17) demonstrated that ARB can survive the washing process. In tests with P. aeruginosa outbreak strains, even the use of temperatures above 50°C could not achieve secure reduction of those strains. Although a 65°C washing program had been used for every wash cycle, it is likely that the temperature in the area of the rubber mantle or the rubber door seal would have been much lower, providing an optimal humid environment and nutrient supply for the growth of Gram-negative microorganisms (26, 28). Moreover, the occasional use of washing machines at low temperatures supports the formation of biofilms (14).

It is important to emphasize that the use of regular domestic washing machines for washing patients’ clothing in a clinical setting is not permitted, according to the current hygiene regulations in Germany. However, the washing machine concerned was located outside the actual central laundry preparation area and was intended only for washing mothers’ clothes and, as in this case, for washing the caps and socks; it was operated exclusively by the nursing staff.

Conclusion.

While previous studies implicated sinks as potential reservoirs for clusters of infection caused by K. oxytoca, this report focuses on the washing machine. The extensive period of the outbreak shows that, with several potential environmental reservoirs, a multidimensional containment approach is necessary. Here, the approach included reinforcement of infection control policies, such as hand hygiene, contact precautions, isolation, admission/routine rectal screening, and clear delineation between handwashing sinks and sinks used for other purposes. However, the ongoing colonization was terminated only after the washing machine was removed and only disposable caps and socks were used. The results suggest that, for prompt management of outbreaks or colonization clusters, the choice of environmental sampling points and the use of effective methods should take into account the ecological properties of the causative strain. Indeed, the environmental strain was not found before the third on-site inspection, as the use of ESwabs allowed better detection.

In addition, the study implies that changes in washing machine design and processing are required to prevent the accumulation of residual water where microbial growth can occur and contaminate clothes. Furthermore, the use of professional washing machines and routine checking with a temperature logger are urgent requirements. In summary, the present study shows that, in situations where an increase in colonization is observed, nonprofessional washing machines, if used, and clothes should be assessed and investigated as potential reservoirs and vectors for transmission.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Investigation strategy.

When the first colonizations were detected in April 2012, an initial management strategy to analyze the cases and to identify possible sources of the K. oxytoca strain was developed. Three major sampling events for all newborns, children, and mothers in the distinct wards took place during the reported time period, following a standard screening procedure.

In March 2013, sampling of specific risk areas (water/wastewater reservoirs) was performed, and ESBL screening (anal swabs and wound swabs) of all HCWs (physicians, nurses, and cleaning personal working in the PNC, the ICU, and the obstetrics department) was conducted to identify possible carriers. In June 2013, further sampling was conducted, using native samples (drinking water and wastewater) and liquid medium swabs (ESwabs).

Laboratory analyses. (i) Microbiological cultivation.

Human and environmental samples were collected, stored at 4°C during transport to the laboratories, and processed within 48 h. All human samples (anal, vaginal, and wound swabs) were streaked onto MacConkey agar plates (Oxoid Deutschland GmbH, Wesel, Germany) with a 10-μg imipenem disk (bioMérieux SA, Marcy-Étoile, France) and selective agar plates, e.g., CHROMagar ESBL plates (Oxoid Deutschland GmbH). Oxoid Rodac contact plates (diameter of 55 mm; Becton, Dickinson, Heidelberg, Germany) were used for environmental surface sampling and were incubated at 36°C ± 1°C for 48 h. All environmental liquid medium swabs (ESwab; Copan Diagnostics, Italy) were streaked on Columbia agar plates containing 5% sheep blood (Becton, Dickinson), MacConkey agar plates (product no. PO5002A; Oxoid Deutschland GmbH), and selective agar plates (e.g., CHROMagar ESBL plates, product no. 43481; bioMérieux), and the plates were incubated at 37°C ± 1°C for 48 h. In addition, casein soy flour peptone broth (CASO broth) (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) was inoculated with the same swabs and incubated at 37°C ± 1°C for 24 h.

The disinfectant wipes, socks, and knitted hats of the newborns were put into 200 ml of CASO broth with Tween-saponin-histidine-cysteine (TSHC) (3% Tween [product no. 8.22187; Merck], 3% saponin [product no. 5185.1; Roth], 0.1% histidine [product no. 1.04351; Merck], 0.1% cysteine [product no. 1.02839; Merck]) and homogenized for 60 s (Stomacher 400 blender; Seward Ltd., West Sussex, United Kingdom). Two 100-ml aliquots of the extract were filtered (Millipore Hydrosol membrane filter, with 250-ml cup), followed by the filtration of 100 ml of 0.9% NaCl to rinse the additives off the filter. The filter was then placed on CHROMagar ESBL and MacConkey agar plates, and the plates were incubated at 37°C for 24 to 48 h. In addition, 100 μl of each concentration of a dilution series in 0.9% NaCl was plated on CHROMagar ESBL and MacConkey agar plates. The emulsions were treated in the same manner as the wipes, except that shredding was not necessary.

For the water samples, approximately 100 ml was collected in a sterile polystyrene cup (product no. 225170; Greiner, Frickenhausen, Germany) and filtered through a sterile nitrocellulose membrane filter (pore size of 0.45 ± 0.02 μm and diameter of 47 mm, with a black grid, product no. EZHAWG 474; Millipore), according to the method described by Schulz and Hartung (29). After filtration, the membrane was placed on selective CHROMagar ESBL and MacConkey agar plates. In addition, 100 μl of each dilution of a dilution series in 0.9% NaCl was plated on CHROMagar ESBL and MacConkey agar plates.

(ii) Identification and susceptibility testing of ARB.

All Enterobacterales strains detected on CHROMagar ESBL plates were identified by an API 20E system with Apiweb v4.1 (bioMérieux) and matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization–time of flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS) (bioMérieux) using Myla software, the Vitek MS-α-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid (CHCA) matrix (product no. 411 071; bioMérieux), and disposable targets (product no. 410 893; bioMérieux). Susceptibility to antibiotics was tested using the Micronaut-S MDR MRGN-Screening 3 system (MERLIN Diagnostika GmbH, Bornheim-Hersel, Germany), and results were interpreted using EUCAST criteria.

(iii) Testing of disinfectant tolerance.

To detect possibly increased tolerance of the K. oxytoca isolates to disinfectants, surface disinfectant and the disinfecting general-purpose detergent that had been used in the washing machines were both examined according to the regulations (methods 7 and 9) of the Disinfectant Commission of the VAH (30). VAH method 7 was used to determine the MICs of the environmental K. oxytoca strains, in comparison with a Gram-negative reference strain, Pseudomonas aeruginosa DSM 939 (31). VAH method 9 is a quantitative suspension test that was used to identify efficacy gaps, taking into account the concentration-time relationship, interfering substances, and temperature of the disinfectants (32–34). The surface disinfectant used was based on quaternary ammonium compounds and alkylamine [didecyldimethylammoniumchloride, 12.5 g/100 g; bis-(aminopropyl)laurylamine, 1.5 g/100 g]. The laundry disinfectant was based on peracetic acid (40 to 80 ppm peracetic acid, 2.5 to 5 g/liter).

Molecular resistance characterization. (i) Molecular characterization of ESBL genes.

Possible ESBL production was confirmed by PCR. Five specific primer sets were used to detect beta-lactamase-encoding genes belonging to the blaTEM, blaSHV, and blaCTX-M families (35–38). The PCR products were visualized by gel electrophoresis on a 1% agarose-Tris-borate-EDTA (TBE) gel and stained with Midori green (Biozym Scientific GmbH, Hessisch Oldendorf, Germany). The resulting amplicons were purified using an innuPREP DOUBLEpure kit (Analytik Jena AG, Jena, Germany), according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. Custom sequencing was performed by Microsynth (Göttingen, Germany). The nucleotide sequences were analyzed using Chromas 2.6.5.

(ii) Plasmid characterization (Inc typing).

To distinguish the Inc types of possible plasmids, 2 or 3 colonies of fresh cultures of all K. oxytoca isolates were resuspended in 100 μl of nuclease-free water, heated to 95°C for 10 min, and centrifuged at 14,000 × g for 5 min. The supernatant was carefully removed and used for PCR. The PCR mixture contained 2× OneTaq master mix (New England Biolabs) and 0.2 μM each primer (Table 4) (39–41).

TABLE 4.

Primers used for Inc typing

| Primer | Sequence | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| IncHI2_fw | TTT CTC CTG AGT CAC CTG TTA ACA C | Carattoli et al. (40) |

| IncHI2_rev | GGC TCA CTA CCG TTG TCA TCC T | Carattoli et al. (40) |

| IncA/C_fw | GAG AAC CAA AGA CAA AGA CCT GGA | Carattoli et al. (40) |

| IncA/C_rev | ACG ACA AAC CTG AAT TGC CTC CTT | Carattoli et al. (40) |

| IncL_fw | CGG AAC CGA CAT GTG CCT ACT | Carattoli et al. (41) |

| IncM_fw | GGA TGA AAA CTA TCA GCA TCT GAA G | Carattoli et al. (41) |

| IncL/M_rev | GAA CTC CGG CGA AAG ACC TTC | Carattoli et al. (41) |

| IncI1-αγ_fw | CGA AAG CCG GAC GGC AGA A | Carattoli et al. (40) |

| IncI1-αγ_rev | TCG TCG TTC CGC CAA GTT CGT | Carattoli et al. (40) |

| IncN_fw | GTC TAA CGA GCT TAC CGA AG | Carattoli et al. (40) |

| IncN_rev | GTT TCA ACT CTG CCA AGT TC | Carattoli et al. (40) |

| IncFIIk_fw | TCT TCT TCA ATC TTG GCG GA | Villa et al. (39) |

| IncFIIk_rev | GCT TAT GTT GCA CRG AAG GA | Villa et al. (39) |

| IncFIA_fw | CCA TGC TGG TTC TAG AGA AGG TG | Carattoli et al. (40) |

| IncFIA_rev | GTA TAT CCT TAC TGG CTT CCG CAG | Carattoli et al. (40) |

| IncFIB_fw | TCT GTT TAT TCT TTT ACT GTC CAC | Villa et al. (39) |

| IncFIB_rev | CTC CCG TCG CTT CAG GGC ATT | Villa et al. (39) |

| IncFII_fw | CTG ATC GTT TAA GGA ATT TT | Villa et al. (39) |

| IncFII_rev | CAC ACC ATC CTG CAC TTA | Villa et al. (39) |

The PCR conditions were set at 94°C for 3 min, followed by 30 cycles of 94°C for 30 s, 60°C for 30 s, and 68°C for 1 min. The final extension was performed at 68°C for 5 min. The PCR products were analyzed using agarose gel electrophoresis on a 1% agarose-TBE gel and were stained with Midori green (Biozym Scientific GmbH).

(iii) Plasmid conjugation testing.

The possibility of plasmid transfer via conjugation was analyzed. All K. oxytoca and wild-type E. coli strains were streaked onto LB agar containing (i) 20 mg/liter chloramphenicol or (ii) 20 mg/liter chloramphenicol and 4 mg/liter cefotaxime. E. coli strains that grew on LB agar containing only chloramphenicol but not on LB agar containing both chloramphenicol and cefotaxime were used for the following conjugation assay. For the preculture, 1 colony of fresh cultures of all isolated K. oxytoca strains (donors) and different wild-type E. coli strains (recipients) were used for inoculation of 5 ml lysogeny broth, and the broth was incubated overnight at 37°C, with shaking. Next, 5 ml of fresh lysogeny broth was inoculated with 100 μl of the donor (K. oxytoca) and 1 ml of the recipient (E. coli) and incubated overnight at 37°C, with shaking. After incubation, 1 ml of each culture was centrifuged at 14,000 rpm for 3 min. Subsequently, the supernatant was discarded and the pellet was resuspended using 100 μl of Milli-Q water. The whole suspensions, as well as 100 μl of the cultures, were plated onto selective LB agar containing 20 mg/liter chloramphenicol and 4 mg/liter cefotaxime and were incubated overnight at 37°C. Grown colonies were streaked onto Columbia sheep blood agar plates and analyzed via MALDI-TOF MS.

(iv) Molecular typing.

All K. oxytoca strains isolated from clinical samples and environmental sources were typed by the GNRC using PFGE, according to the method described by Tenover et al. (42) and modified as described by Ribot et al. (43). In addition, multilocus sequence typing (MLST) of all K. oxytoca strains was conducted. Briefly, bacteria were cultivated overnight at 35°C on Columbia blood agar plates. After resuspension of 2 or 3 colonies in 80 μl of PCR water, the samples were heated to 95°C for 5 min and centrifuged at 14,000 × g for 5 min. The supernatant was used for PCR according to the protocol described by Herzog et al. (44). The PCR products were purified by extraction from a 1% agarose gel using the GeneJET gel extraction kit (Fisher Scientific GmbH, Schwerte, Germany), according to the manufacturer’s recommendations, and were sequenced by GATC Biotech AG (Constance, Germany). Assignment to the ST was performed via the specific MLST website (https://pubmlst.org/koxytoca).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We gratefully acknowledge the consent of the hospital involved and the collaborating laboratories to publish. Special thanks go to Anja Schallenberg, Cathrin Albert, and Gero Wilbring for their constant support during the reporting period.

No funding sources are declared.

No conflicts of interest are declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Rutala WA, Weber DJ. 1997. Water as a reservoir of nosocomial pathogens. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 18:609–616. doi: 10.2307/30141486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sib E, Voigt AM, Wilbring G, Schreiber C, Faerber HA, Skutlarek D, Parcina M, Mahn R, Wolf D, Brossart P, Geiser F, Engelhart S, Exner M, Bierbaum G, Schmithausen RM. 2019. Antibiotic resistant bacteria and resistance genes in biofilms in clinical wastewater networks. Int J Hyg Environ Health 222:655–662. doi: 10.1016/j.ijheh.2019.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Müller H, Sib E, Gajdiss M, Klanke U, Lenz-Plet F, Barabasch V, Albert C, Schallenberg A, Timm C, Zacharias N, Schmithausen RM, Engelhart S, Exner M, Parcina M, Schreiber C, Bierbaum G. 2018. Dissemination of multi-resistant Gram-negative bacteria into German wastewater and surface waters. FEMS Microbiol Ecol 94:fiy057. doi: 10.1093/femsec/fiy057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kanamori H, Weber DJ, Rutala WA. 2016. Healthcare outbreaks associated with a water reservoir and infection prevention strategies. Clin Infect Dis 62:1423–1435. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciw122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kizny Gordon AE, Mathers AJ, Cheong EYL, Gottlieb T, Kotay S, Walker AS, Peto TEA, Crook DW, Stoesser N. 2017. The hospital water environment as a reservoir for carbapenem-resistant organisms causing hospital-acquired infections: a systematic review of the literature. Clin Infect Dis 64:1435–1444. doi: 10.1093/cid/cix132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lowe C, Willey B, O’Shaughnessy A, Lee W, Lum M, Pike K, Larocque C, Dedier H, Dales L, Moore C, McGeer A. 2012. Outbreak of extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Klebsiella oxytoca infections associated with contaminated handwashing sinks. Emerg Infect Dis 18:1242–1247. doi: 10.3201/eid1808.111268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jeong SH, Kim WM, Chang CL, Kim JM, Lee K, Chong Y, Hwang HY, Baek YW, Chung HK, Woo IG, Ku JY. 2001. Neonatal intensive care unit outbreak caused by a strain of Klebsiella oxytoca resistant to aztreonam due to overproduction of chromosomal β-lactamase. J Hosp Infect 48:281–288. doi: 10.1053/jhin.2001.1018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schulz-Stübner S, Kniehl E. 2011. Transmission of extended-spectrum β-lactamase Klebsiella oxytoca via the breathing circuit of a transport ventilator: root cause analysis and infection control recommendations. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 32:828–829. doi: 10.1086/661225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Decré D, Burghoffer B, Gautier V, Petit JC, Arlet G. 2004. Outbreak of multi-resistant Klebsiella oxytoca involving strains with extended-spectrum β-lactamases and strains with extended-spectrum activity of the chromosomal β-lactamase. J Antimicrob Chemother 54:881–888. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkh440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zárate MS, Gales AC, Picão RC, Pujol GS, Lanza A, Smayevsky J. 2008. Outbreak of OXY-2-producing Klebsiella oxytoca in a renal transplant unit. J Clin Microbiol 46:2099–2101. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00194-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Leitner E, Zarfel G, Luxner J, Herzog K, Pekard-Amenitsch S, Hoenigl M, Valentin T, Feierl G, Grisold AJ, Högenauer C, Sill H, Krause R, Zollner-Schwetz I. 2015. Contaminated handwashing sinks as the source of a clonal outbreak of KPC-2-producing Klebsiella oxytoca on a hematology ward. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 59:714–716. doi: 10.1128/AAC.04306-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gaillot O, Maruéjouls C, Abachin E, Lecuru F, Arlet G, Simonet M, Berche P. 1998. Nosocomial outbreak of Klebsiella pneumoniae producing SHV-5 extended-spectrum β-lactamase, originating from a contaminated ultrasonography coupling gel. J Clin Microbiol 36:1357–1360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gastmeier P, Groneberg K, Weist K, Rüden H. 2003. A cluster of nosocomial Klebsiella pneumoniae bloodstream infections in a neonatal intensive care department: identification of transmission and intervention. Am J Infect Control 31:424–430. doi: 10.1067/mic.2003.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bloomfield SF, Cookson B, Falkiner F, Griffith C, Cleary V. 2007. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, Clostridium difficile, and extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli in the community: assessing the problem and controlling the spread. Am J Infect Control 35:86–88. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2006.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Callewaert C, Van Nevel S, Kerckhof FM, Granitsiotis MS, Boon N. 2015. Bacterial exchange in household washing machines. Front Microbiol 6:1381. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2015.01381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Voskoboinik L, Amiel M, Reshef A, Gafny R, Barash M. 2018. Laundry in a washing machine as a mediator of secondary and tertiary DNA transfer. Int J Legal Med 132:373–378. doi: 10.1007/s00414-017-1617-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rehberg L, Frontzek A, Melhus Å, Bockmühl DP. 2017. Prevalence of β-lactamase genes in domestic washing machines and dishwashers and the impact of laundering processes on antibiotic resistant bacteria. J Appl Microbiol 123:1396–1406. doi: 10.1111/jam.13574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sehulster LM, Chinn RYW, Arduino MJ, Carpenter J, Donlan R, Ashford D, Besser R, Fields B, McNeil MM, Whitney C, Wong S, Juranek D, Cleveland J. 2004. Guidelines for environmental infection control in health-care facilities: recommendations of CDC and the Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee (HICPAC). American Society for Healthcare Engineering/American Hospital Association, Chicago, IL. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Magiorakos AP, Srinivasan A, Carey RB, Carmeli Y, Falagas ME, Giske CG, Harbarth S, Hindler JF, Kahlmeter G, Olsson-Liljequist B, Paterson DL, Rice LB, Stelling J, Struelens MJ, Vatopoulos A, Weber JT, Monnet DL. 2012. Multidrug-resistant, extensively drug-resistant and pandrug-resistant bacteria: an international expert proposal for interim standard definitions for acquired resistance. Clin Microbiol Infect 18:268–281. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2011.03570.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rodríguez I, Thomas K, Van Essen A, Schink AK, Day M, Chattaway M, Wu G, Mevius D, Helmuth R, Guerra B. 2014. Chromosomal location of blaCTX-M genes in clinical isolates of Escherichia coli from Germany, the Netherlands and the UK. Int J Antimicrob Agents 43:553–557. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2014.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Price JR, Cole K, Bexley A, Kostiou V, Eyre DW, Golubchik T, Wilson DJ, Crook DW, Walker AS, Peto TEA, Llewelyn MJ, Paul J. 2017. Transmission of Staphylococcus aureus between health-care workers, the environment, and patients in an intensive care unit: a longitudinal cohort study based on whole-genome sequencing. Lancet Infect Dis 17:207–214. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(16)30413-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Heudorf U, Gasteyer S, Müller M, Serra N, Westphal T, Reinheimer C, Kempf V. 2017. Handling of laundry in nursing homes in Frankfurt am Main, Germany, 2016: laundry and professional clothing as potential pathways of bacterial transfer. GMS Hyg Infect Control 12:Doc20. doi: 10.3205/dgkh000305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.World Health Organization. 2019. Critically important antimicrobials for human medicine, 6th revision World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jolley KA, Bray JE, Maiden M. 2018. Open-access bacterial population genomics: BIGSdb software, the PubMLST.org website and their applications. Wellcome Open Res 3:124. doi: 10.12688/wellcomeopenres.14826.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dögen A, Sav H, Gonca S, Kaplan E, Ilkit M, Novak Babic M, Gunde-Cimerman N, de Hoog GS. 2017. Candida parapsilosis in domestic laundry machines. Med Mycol 55:813–819. doi: 10.1093/mmy/myx008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gattlen J, Amberg C, Zinn M, Mauclaire L. 2010. Biofilms isolated from washing machines from three continents and their tolerance to a standard detergent. Biofouling 26:873–882. doi: 10.1080/08927014.2010.524297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang J, Li W, Chen J, Qi W, Wang F, Zhou Y. 2018. Impact of biofilm formation and detachment on the transmission of bacterial antibiotic resistance in drinking water distribution systems. Chemosphere 203:368–380. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2018.03.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Amberg C. 2014. Biofilm in washing machines and how it is assessed. Presented at Hygiene Requirements and Measurements in Dishwashing, 1 to 2 April 2014, Bonn, Germany. https://www.swissatest.ch/files/downloads/c38bc1b8ff88db0257d6ba6287a8daf2/Biofilm%20in%20washing%20machines%20and%20how%20it%20is%20assessed.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schulz J, Hartung J. 2009. Nachweis von MRSA in Schweinestallluft mit Impingement und nachfolgender Membranfiltration. Gefahrst Reinhalt Luft 9:348–352. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Verbund für Angewandte Hygiene e.V. 2016. Anforderungen und Methoden zur VAH-Zertifizierung chemischer Desinfektionsverfahren. mhp, Wiesbaden, Germany. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Verbund für Angewandte Hygiene e.V. 2016. Bestimmung der bakteriostatischen und levurostatischen Wirksamkeit sowie geeigneter Neutralisationsmittel (VAH Methode 7), p 7-1–7-3 In Anforderungen und Methoden zur VAH-Zertifizierung chemischer Desinfektionsverfahren. mhp, Wiesbaden, Germany. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Verbund für Angewandte Hygiene e.V. 2016. Bestimmung der bakteriziden, levuroziden, fungiziden, tuberkuloziden bzw. mykobakteriziden Wirksamkeit im quantitativen Suspensionsversuch (VAH Methode 9), p 9-1–9-10 In Anforderungen und Methoden zur VAH-Zertifizierung chemischer Desinfektionsverfahren. mhp, Wiesbaden, Germany. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Verbund für Angewandte Hygiene e.V. 2016. Zur Äquivalenz der Desinfektionsmittel-Testung gemäß VAH-Methoden und der Testung gemäß den aktuellen europäischen Normen. Hyg Med 41:41–43. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Deutsches Institut für Normung. 2014. Chemische Desinfektionsmittel und Antiseptika - Quantitativer Suspensionsversuch zur Prüfung der fungiziden Wirkung chemischer Desinfektionsmittel im humanmedizinischen Bereich - Prüfverfahren und Anforderungen (Phase 2, Stufe 1). DIN EN 13727:2014-03 Deutsches Institut für Normung, Berlin, Germany. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Paterson DL, Mulazimoglu L, Casellas JM, Ko WC, Goossens H, Von Gottberg A, Mohapatra S, Trenholme GM, Klugman KP, McCormack JG, Yu VL. 2000. Epidemiology of ciprofloxacin resistance and its relationship to extended-spectrum β-lactamase production in Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates causing bacteremia. Clin Infect Dis 30:473–478. doi: 10.1086/313719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Grimm V, Ezaki S, Susa M, Knabbe C, Schmid RD, Bachmann TT. 2004. Use of DNA microarrays for rapid genotyping of TEM β-lactamases that confer resistance. J Clin Microbiol 42:3766–3774. doi: 10.1128/JCM.42.8.3766-3774.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gröbner S, Linke D, Schütz W, Fladerer C, Madlung J, Autenrieth IB, Witte W, Pfeifer Y. 2009. Emergence of carbapenem-non-susceptible extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates at the university hospital of Tübingen, Germany. J Med Microbiol 58:912–922. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.005850-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Geser N, Stephan R, Hächler H. 2012. Occurrence and characteristics of extended-spectrum β-lactamase (ESBL) producing Enterobacteriaceae in food producing animals, minced meat and raw milk. BMC Vet Res 8:21. doi: 10.1186/1746-6148-8-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Villa L, García-Fernández A, Fortini D, Carattoli A. 2010. Replicon sequence typing of IncF plasmids carrying virulence and resistance determinants. J Antimicrob Chemother 65:2518–2529. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkq347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Carattoli A, Bertini A, Villa L, Falbo V, Hopkins KL, Threlfall EJ. 2005. Identification of plasmids by PCR-based replicon typing. J Microbiol Methods 63:219–228. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2005.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Carattoli A, Seiffert SN, Schwendener S, Perreten V, Endimiani A. 2015. Differentiation of IncL and IncM plasmids associated with the spread of clinically relevant antimicrobial resistance. PLoS One 10:e0123063. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0123063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tenover FC, Arbeit RD, Goering RV, Mickelsen PA, Murray BE, Persing DH, Swaminathan B. 1995. Interpreting chromosomal DNA restriction patterns produced by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis: criteria for bacterial strain typing. J Clin Microbiol 33:2233–2239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ribot EM, Fair MA, Gautom R, Cameron DN, Hunter SB, Swaminathan B, Barrett TJ. 2006. Standardization of pulsed-field gel electrophoresis protocols for the subtyping of Escherichia coli O157:H7, Salmonella, and Shigella for PulseNet. Foodborne Pathog Dis 3:59–67. doi: 10.1089/fpd.2006.3.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Herzog KA, Schneditz G, Leitner E, Feierl G, Hoffmann KM, Zollner-Schwetz I, Krause R, Gorkiewicz G, Zechner EL, Högenauer C. 2014. Genotypes of Klebsiella oxytoca isolates from patients with nosocomial pneumonia are distinct from those of isolates from patients with antibiotic-associated hemorrhagic colitis. J Clin Microbiol 52:1607–1616. doi: 10.1128/JCM.03373-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]