Abstract

BACKGROUND/OBJECTIVES:

Most people with Alzheimer disease and related dementias will experience agitated and/or aggressive behaviors during the later stages of the disease. These behaviors cause significant stress for people living with dementia and their caregivers, including nursing home (NH) staff. Addressing these behaviors without the use of chemical restraints is a growing focus of policy makers and professional organizations. Unfortunately, evidence for nonpharmacological strategies for addressing dementia-related behaviors is lacking.

DESIGN:

Six-month, preintervention-postintervention pilot study.

SETTING:

US NHs (n = 4).

PARTICIPANTS:

Residents with advanced dementia (n = 45).

INTERVENTION:

Music & Memory, an individualized music program in which the music a resident preferred when she/he was young is delivered at early signs of agitation, using a personal music player.

MEASUREMENTS:

Dementia-related behaviors for the same residents were measured three ways: (1) observationally using the Agitation Behavior Mapping Instrument (ABMI); (2) staff report using the Cohen-Mansfield Agitation Inventory (CMAI); and (3) administratively using the Minimum Data Set–Aggressive Behavior Scale (MDS-ABS).

RESULTS:

ABMI score was 4.1 (SD = 3.0) preintervention while not listening to the music, 4.4 (SD = 2.3) postintervention while not listening to the music, and 1.6 (SD = 1.5) postintervention while listening to music (P < .01). CMAI score was 61.2 (SD = 16.3) preintervention and 51.2 (SD = 16.1) postintervention (P < .01). MDS-ABS score was 0.8 (SD = 1.6) preintervention and 0.7 (SD = 1.4) postintervention (P = .59).

CONCLUSION:

Direct observations were most likely to capture behavioral responses, followed by staff interviews. Nursing-home based, pragmatic trials that rely solely on available administrative data may fail to detect effects of nonpharmaceutical interventions on behaviors. Findings are relevant to evaluations of nonpharmaceutical strategies for addressing behaviors in NHs, and will inform a large, National Institute on Aging-funded pragmatic trial beginning spring 2019.

Keywords: behavior, dementia, music, nursing homes, pragmatic clinical trials as topic

Most people with Alzheimer disease and related dementias (ADRDs) will experience agitated and/or aggressive behaviors during the later stages of the disease.1 Addressing these behaviors without the use of chemical restraints is a growing focus of policy makers and funders, including the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services.2 The Alzheimer’s Association’s official position statement on dementia-related behaviors recommends nonpharmacological approaches for addressing behaviors, but notes “large population-based trials rigorously supporting the evidence of benefit for non-pharmacological therapies are presently lacking,”3(p2) and the quality of existing studies of music-based interventions for people with dementia varies greatly.4 In this short report, we present the findings from a pilot study of one popular nonpharmacological, music-based intervention, Music & Memory.

Music & Memory is a personalized music program for people with ADRD. Emerging science indicates that early musical memories are stored in a part of the brain that remains intact until the later stages of ADRD.5 Based on the unmet needs model for behaviors in ADRD of Cohen-Mansfield et al., we hypothesize that personalized music (or eliciting familiar musical memories) may reduce agitated behaviors in nursing home (NH) residents with ADRD by addressing boredom, sensory deprivation, anxiety, or loneliness.6 The purpose of this pilot work was to identify the optimal measurement strategy for a large, cluster-randomized trial.

METHODS

Participants

Four NHs participated in the pilot, one from each multifacility corporation recruited to participate in the larger trial. To be eligible to receive the intervention, residents must: have lived in one of the pilot NHs for at least 90 days as of January 1, 2018; have an active ADRD diagnosis; and have evidence of moderate to severely impaired daily decision making.

Intervention

Through interviews with family members and residents’ reactions, NH staff identified the music a resident preferred when she/he was between the ages of 16 and 26 years old. This preferred music was downloaded to a personalized music device. Certified nursing assistants were taught to use the music at times of the day when behaviors were likely to occur.

Design

Changes in behaviors were assessed using a preintervention-postintervention design.

Measures

We measured agitated and aggressive behaviors in three ways: (1) directly observing residents’ behaviors; (2) interviewing staff members about residents’ behaviors; and (3) using available administrative data on residents’ behaviors. The tool used to directly observe resident behaviors was the Agitation Behavior Mapping Instrument (ABMI).7 Research staff observed residents for short intervals (3 minutes per observation) and recorded the number of times 14 specific verbally and physically agitated behaviors occurred (range = 0-140, with higher scores indicating more agitated behaviors). The tool used to interview staff about residents’ behaviors was the Cohen-Mansfield Agitation Inventory (CMAI).8 Research staff interviewed a nursing staff member who knew the resident well to ask how frequently 29 agitated behaviors occurred in the past week. Response choices for each item ranged from never (1) to several times per hour (7); total score ranged from 29 to 203, with higher scores indicating more agitated behaviors.

Administrative data were collected from a standardized resident assessment instrument, the Minimum Data Set (MDS), version 3.0.9 The MDS includes four items related to the frequency of (1) physical behavioral symptoms directed toward others; (2) verbal behavioral symptoms directed toward others; (3) other behavioral symptoms not directed toward others; and (4) behaviors related to resisting necessary care. Frequency in the past week is reported as: behavior not exhibited (0); behavior occurred 1 to 3 days (1); behavior occurred 4 to 6 days (2); or behavior occurred daily (3). These four items were summed to create the MDS–Aggressive Behavior Scale (ABS) (range = 0-12, with higher scores indicating more agitated behaviors).10

Procedures

Study researchers visited each facility for 2 days before the intervention began (baseline) and 2 days at the end of the 6-month pilot (follow-up). Staff interviews were completed on the first day of each visit; direct observations were completed on the second day. Each resident was observed five times during the second day: between 8 and 10 am; between 11 am and 1 pm; between 4 and 6 pm; and at two times determined by the data collector (unscheduled observations). At least one observation was during a meal and one was during an activity.

At the baseline visit, staff identified residents to whom they intended to offer the intervention. Direct observations and staff interviews were collected for selected residents. At the follow-up visit, direct observations and staff interviews were collected for the same residents. Administrative assessments were then linked (at the person level) to the primary data as follows: the administrative assessment occurring no more than 60 days before or 30 days after the baseline visit was linked to the baseline staff interview and observation data; and the administrative assessment occurring after the baseline assessment and closest in time to the follow-up visit (maximum, 60 days after the follow-up visit) was linked to the follow-up staff interview and observation data. Average days between measures collected during site visit and linked MDS-ABS measure was 30.1 days (SD = 17.9 days). Data collection was approved by the Brown University Institutional Review Board (protocol 1705001793).

Analysis

Wilcoxon signed-rank tests with continuity correction were used to compare baseline and follow-up scores on the three measures of behaviors. Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient was used to describe the relationship between measures for the same resident at the same time point. All analyses were conducted using STATA, SE Version 15.

RESULTS

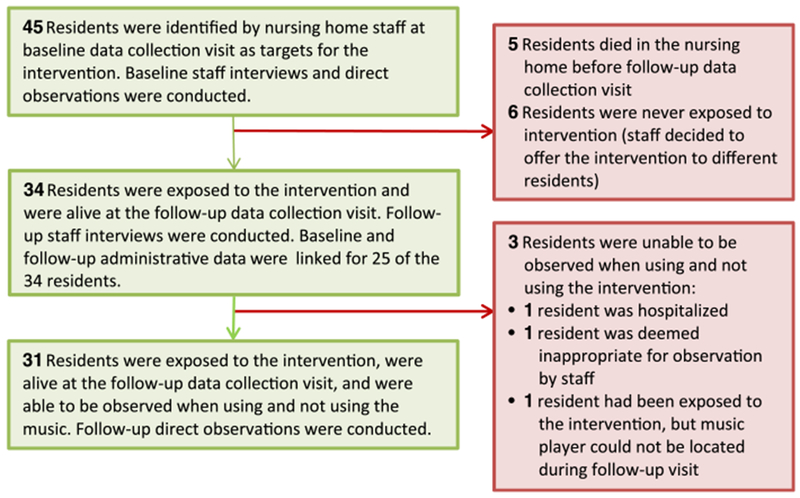

Staff in the four participating NHs identified 45 residents at baseline (at least 10 per NH), to whom they intended to offer the Music & Memory program (Figure 1). Baseline staff interviews (CMAI) and direct observations (ABMI) were conducted for these residents. Of the 45 residents identified by NH staff at baseline, 5 died before follow-up and 6 were never exposed to the intervention (staff decided to offer the program to different residents, not initially identified). At the follow-up visit, 34 residents were alive and had been exposed to the program; follow-up staff interviews (CMAI) were collected for these residents. Of the 34 residents alive and exposed at follow-up, 31 were able to be directly observed (ABMI) when using and not using the music (1 resident was hospitalized, 1 resident was deemed inappropriate for observation, and 1 resident had been exposed to the music, but the player was missing during the follow-up visit). Baseline and follow-up administrative data were linked for 25 of the 34 residents who were alive and had been exposed at follow-up.

Figure 1.

This figure outlines the flow of participants through the 6-month pilot study and describes, in detail, the reasons for incomplete follow-up, including: death in the nursing home; lack of planned exposure to the music; and inability to observe residents during site visit.

Within-person changes in agitated and aggressive behaviors are presented in Table 1. The largest decreases in agitated behaviors were detected through direct observation of residents. At baseline, the average total ABMI score was 4.1 (SD = 3.0). At follow-up, the average total ABMI score was 4.4 (SD = 2.3) for observations without the music and 1.6 (SD = 1.5) for observations with the music (P < .01). Moderate decreases in agitated behaviors were detected through staff interviews. Average total CMAI score was 61.2 (SD = 16.3) at baseline and 51.2 (SD = 16.1) at follow-up (P < .01). No significant decreases in agitated behaviors were detected using available administrative data (MDS-ABS score at baseline = 0.7 [SD = 1.5]; MDS-ABS score at follow-up = 0.6 [SD = 1.6]).

Table 1.

Within-Person Change in Agitated and/or Aggressive Behaviors Before and After Music & Memory Intervention

| Mean (SE) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Frequency of behaviors at baseline visit | Frequency of behaviors at follow-up visit | Average within-person difference in frequency of behaviors | Average within-person % change in frequency of behaviors |

| Direct observation (N = 31) (Agitated Behavior Mapping Instrument [study range = 0-22])a | 4.1 (3.0) | 4.4 (2.3)b 1.6 (1.5)c | −2.8 (2.3)d | −60 |

| Staff interview (N = 34) (Cohen-Mansfield Agitation Inventory [study range = 29-103])a | 61.2 (16.3) | 51.2 (16.1) | −10.0 (18.9)d | −16 |

| Administrative data (N = 25) (Minimum Data Set–Aggressive Behavior Scale [study range = 0-7])a | 0.7 (1.5) | 0.6 (1.6) | −0.1 (1.2) | −14 |

Note: Causality was not implied.

Higher scores on measure indicate worse (more frequent) behaviors.

Frequency of behaviors when not using the music.

Frequency of behaviors when using the music.

P < .01, paired t-test with continuity correction.

Spearman’s rank correlation coefficients (ρ) for the linked measures were: staff interview (CMAI) and administrative measure (MDS-ABS) = 0.30 (P = .01); and direct observations (ABMI) and administrative measures (MDS-ABS) = 0.34 (P < .01).

DISCUSSION

In this pilot study, direct observational measures captured large decreases in behaviors when residents were using the music. Staff interviews about resident behaviors captured moderate decreases in behaviors after residents were exposed to the music. The MDS-based measure did not capture differences in behaviors after exposure to the music. We found modest correlations (p = 0.30-0.34) between primary data collected on-site and administrative measures of behaviors.

There is growing interest in large-scale, effectiveness trials of nonpharmacological approaches for addressing behaviors in NH residents with ADRD. Using routinely collected administrative data to assess outcomes for participants is one way to increase pragmatism in study eligibility11–13 and contain study costs. Unfortunately, available administrative measures of behaviors systematically underdetect behaviors14,15 and, based on our preliminary findings, may not be sensitive to changes in behaviors over time.

In addition to cost and sensitivity to change, it is important to consider which measure is most relevant for the study outcome of interest. The MDS likely measures the frequency of any behaviors that were serious enough to be charted in the past week16; the CMAI measures the frequency of behaviors in the past week, as crudely recalled by a staff person who knows the resident well; and the ABMI measures the frequency of behaviors over short intervals, as recorded by a trained observer. The harm that we are trying to avoid is the use of drugs to address behaviors by “snowing” residents, thereby increasing risk of falls.17 Thus, we need to be able to show an effect at the point where drugs and their alternatives are considered. The ABMI, while costly and not pragmatic to collect, allows us to measure the effect of nondrug interventions at this decision point.

There are limitations to our study protocol that reflect the state of the evidence for nonpharmacological approaches. The decision to focus on music residents liked when they were younger was based on work suggesting: (1) long-known music is stored in parts of the brain later affected in the Alzheimer disease course5; and (2) music from when people with Alzheimer disease were between the ages of 10 and 30 years was more likely to evoke autobiographical memories than popular music from later in their lives.18 However, we recognize this evidence is preliminary. We expect longitudinal neuroimaging will continue to help us understand the mechanisms through which different types of music may affect specific behaviors in dementia.19 More careful tailoring of nonpharmaceutical interventions, based on the presumed determinants of the target behaviors, is needed.20

There are limitations to our study protocol that reflect the pragmatic nature of this work, such as focusing on preferred music from when the resident was between the ages of 16 and 26 years. While there are tools for identifying music that was important to residents throughout their lives,21 such as music from early childhood, seasonal favorites, or religious music, these tools generally rely on family input. Unfortunately, many NH residents with dementia do not have a family member involved in their care.22 By specifying an arbitrary age range, NH staff can identify popular songs by genre and decade to test with the resident. Identifying a resident’s preferred music is a time-consuming process and a barrier to successful implementation. Shortcuts are needed to help NH staff identify music, when family input is not available.

Pragmatic study considerations affected our measurement. The interrater reliability of the CMAI is poor to good; only about half of the items have interrater correlation coefficients above 0.5.23 The same staff member was interviewed at baseline and follow-up whenever possible (approximately 70% of the time). Another pragmatic limitation of our measurement strategy was the number of direct observations per resident. Ideally, we would observe each resident, every half hour, over the course of several days.24 To partially address this limitation, in the full trial we will compare observations completed under similar conditions, including: time of day; location of the resident; what activities she/he was involved in; sound and light level; and the number of other people in the room.

Our results are also limited by the small sample and the preintervention-postintervention study design. These limitations will be addressed in the next phase of this research, a cluster-randomized trial in 81 NHs. We have designed an efficacy/effectiveness hybrid trial, in which we will collect direct observations and staff interviews for a randomly selected subset of participants and administrative data for all participants. This hybrid trial design is described in more detail in the National Institute on Aging, Stage Model for Behavioral Intervention Development (Stage III).25,26 Our lessons learned, specifically regarding measurement of behaviors, have implications for testing of other nonpharmaceutical therapies in the NH setting.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Financial Disclosure: This work is supported by the National Institute on Aging (R21AG057451).

Sponsor’s Role: The sponsor did not have a role in the design, methods, subject recruitment, data collection, analysis, and preparation of the article.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors have no conflicts.

REFERENCES

- 1.Zuidema S, Koopmans R, Verhey F. Prevalence and predictors of neuropsychiatric symptoms in cognitively impaired NH patients. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 2007;20:41–49. 10.1177/0891988706292762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Maust DT, Kim HM, Chiang C, Kales HC. Association of the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services’ national partnership to improve dementia care with the use of antipsychotics and other psychotropics in long-term care in the United States from 2009 to 2014. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178:640–647. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.0379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alzheimer’s Association. Dementia-Related Behaviors Statement. Alzheimer’s Association Website. http://www.alz.org/about/statements Published 2015. Accessed January 25, 2019.

- 4.van der Steen JT, Smaling HJ, van der Wouden JC, Bruinsma MS, Scholten RJ, Vink AC. Music-based therapeutic interventions for people with dementia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;7:CD003477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jacobsen JH, Stelzer J, Fritz TH, Chetelat G, La Joie R, Turner R. Why musical memory can be preserved in advanced Alzheimer’s disease. Brain. 2015; 138:2438–2450. 10.1093/brain/awv135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cohen-Mansfield J, Dakheel-Ali M, Marx MS, Thein K, Regier NG. Which unmet needs contribute to behavior problems in persons with advanced dementia? Psychiatry Res. 2015;228(1):59–64. 10.1016/j.psychres.2015.03.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cohen-Mansfield J, Werner P, Marx M. An observational study of agitation in agitated NH residents. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 1989;1(2):153–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cohen-Mansfield J, Marx MS, Rosenthal AS. A description of agitation in a NH. J Gerontol Med Sci. 1989a;44(3):M77–M84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Saliba D, Jones M, Streim J, Ouslander J, Berlowitz D, Buchanan J. Overview of significant changes in the Minimum Data Set for NHs version 3.0. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2012;13(7):595–601. 10.1016/j.jamda.2012.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Perlman CM, Hirdes JP. The aggressive behavior scale: a new scale to measure aggression based on the Minimum Data Set. J Am Geriatr Soc 2008;56 (12):2298–2303. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.02048.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lipman P, Loudon K, Dluzak L, Moloney R, Messner D, Stoney C. Framing the conversation: use of PRECIS-2 ratings to advance understanding of pragmatic trial design domains. Trials. 2017;18:532 10.1186/s13063-017-2267-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zimmerman S, Sloane P. Making pragmatic trials pragmatic in post-acute and long-term care settings. 2019;20(2):107–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Beattie E, O’Reilly M, Fetherstonhaugh D, McMaster M, Moyle W, Fielding E. Supporting autonomy of NH residents with dementia in the informed consent process. Dementia. 2018;1–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bharucha AJ, Vasilescu M, Dew MA, et al. Prevalence of behavioral symptoms: comparison of the Minimum Data Set assessments with research instruments. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2008;9:244–250. 10.1016/j.jamda.2018.12.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Saliba D, Buchanan J. Development and Validation of a Revised NH Assessment Tool: MDS 3.0. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Website. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/NursingHomeQualityInits/downloads/MDS30FinalReport.pdf Published 2008. Accessed October 10, 2018.

- 16.Leibovici A Beyond the minimum data set: measuring disruptive behaviors in NH residents: do we need better psychometrics or simply different metrics? J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2008;9:211–212. 10.1016/j.jamda.2007.12.093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fraser LA, Liu K, Naylor KL, Hwang YJ, Dixon SN, Shariff SZ, Garg AX Falls and fractures with atypical antipsychotic medication use: a population-based cohort study. JAMA Intern Med 2015;175(3):450–452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Baird A, Brancatisano O, Gelding R, Thompson WF. Characterization of music and photograph evoked autobiographical memories in people with Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2018;66(2):693–706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vemuri P, Fields J, Peter J, Kloppel S. Cognitive interventions in Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s diseases: emerging mechanisms and role of imaging. Curr Opin Neurol 2016;29(4):405–411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kolanowski A, Fortinsky RH, Calkins M, et al. Advancing research on care needs and supportive approaches for persons with dementia: recommendations and rationale. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2018;19(12):1047–1053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gerdner LA. Individualized music for dementia: evolution and application of evidence-based protocol. World J Psychiatry. 2012;2(2):26–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McCreedy E, Loomer L, Palmer JA, Mitchell SL, Volandes A, Mor V. Representation in the care planning process for nursing home residents with dementia. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2018;19(5):415–421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zuidema SU, Buursema AL, Gerritsen MG, et al. Assessing neuropsychiatric symptoms in nursing home patients with dementia: reliability and Reliable Change Index of the Neuropsychiatric Inventory and the Cohen-Mansfield Agitation Inventory. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2011;26(2):127–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cohen-Mansfield J, Libin A, Marx MS. Nonpharmacological treatment of agitation: a controlled trial of systematic individualized intervention. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2007;62(8):908–916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.National Institute on Aging. Stage Model for Behavioral Intervention Development. National Institute on Aging Website. https://nia.nih.gov/research/-dbsr/stage-model-behavioral-intervention-development Accessed January 28, 2019.

- 26.Onken LS, Carrol KM, Shoham V, Cuthbert BN, Riddle M. Reenvisioning clinical science: unifying the discipline to improve the public health. Clin Psychol Sci. 2014;2(1):22–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]