Abstract

Elongation factor thermal unstable Tu (EF-Tu) is a G protein that catalyzes the binding of aminoacyl-tRNA to the A-site of the ribosome inside living cells. Structural and biochemical studies have described the complex interactions needed to effect canonical function. However, EF-Tu has evolved the capacity to execute diverse functions on the extracellular surface of both eukaryote and prokaryote cells. EF-Tu can traffic to, and is retained on, cell surfaces where can interact with membrane receptors and with extracellular matrix on the surface of plant and animal cells. Our structural studies indicate that short linear motifs (SLiMs) in surface exposed, non-conserved regions of the molecule may play a key role in the moonlighting functions ascribed to this ancient, highly abundant protein. Here we explore the diverse moonlighting functions relating to pathogenesis of EF-Tu in bacteria and examine putative SLiMs on surface-exposed regions of the molecule.

Keywords: EF-Tu, moonlighting, bacteria, adhesion, chaperone activities

Introduction

Elongation Factor Thermo Unstable (EF-Tu) is one the most abundant proteins found in bacteria, comprising up to 6% of the total protein expressed in Escherichia coli (Furano, 1975) and as high as 10% of the total protein expressed in the genome reduced pathogen Mycoplasma pneumoniae (Dallo et al., 2002). The primary, canonical function of EF-Tu is to transport aminoacylated tRNAs to the ribosome (Sprinzl, 1994). Ef-Tu has been a therapeutic target for antibiotics (elfamycins) since the 1970s (Wolf et al., 1974; Prezioso et al., 2017). However, current issues with elfamycins’ poor pharmacokinetics and solubility has prevented their commercialization as therapeutic agents (Prezioso et al., 2017).

Diverse functions have been ascribed to EF-Tu many of which include important virulence traits in Gram positive and Gram-negative pathogenic bacteria. To effect alternate virulence-associated functions, including adhesion to host extracellular matrix components, EF-Tu must gain access and be retained on the extracellular surface. This poses a challenge as signal secretion motifs are absent in this highly structured protein, and motifs required for binding diverse host cell surface receptor and matrix molecules must evolve without jeopardizing structural constraints needed to execute canonical function as a G protein. Here we refer to secondary functions as “moonlighting” functions. The concept of protein moonlighting is well established in eukaryotes (Jeffery, 1999; Huberts and van der Klei, 2010; Petit et al., 2014; Min et al., 2016; Yoon et al., 2018), and is rapidly gaining traction in prokaryotes (Henderson and Martin, 2011, 2013; Wang et al., 2013b; Kainulainen and Korhonen, 2014; Jeffery, 2018; Ebner and Götz, 2019) indicating that it is an ancient and evolutionally conserved phenomenon. Although EF-Tu executes various functions in eukaryotes, a review of the moonlighting roles of EF-Tu in bacteria is lacking. Therefore, this review has a focus to discuss the ever-expanding moonlighting roles of EF-Tu in prokaryotes, and how these roles relate to pathogenesis.

Structure and Function of EF-Tu

Structural Analysis of EF-Tu

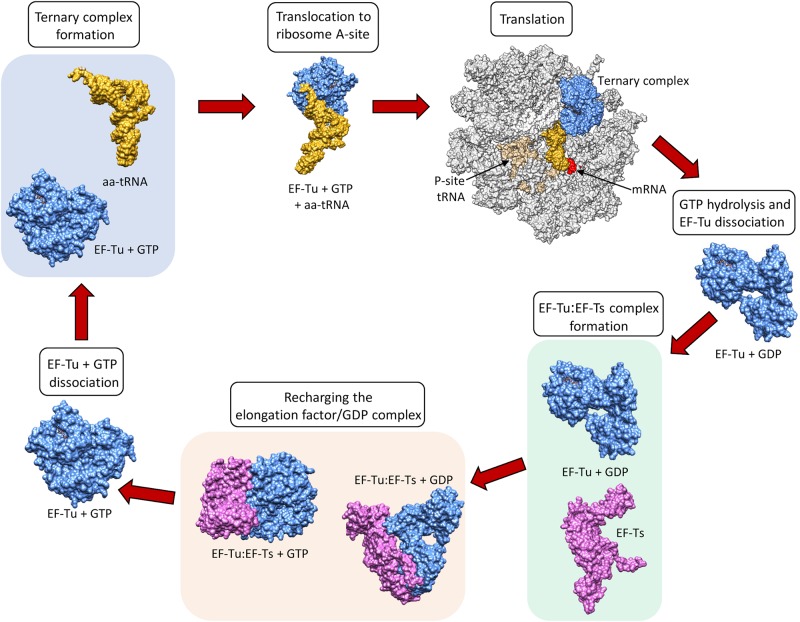

Elongation factors (Table 1) in bacteria (e.g., EF-Tu also known as EF1A) and in eukaryotes (e.g., the eukaryotic Elongation Factor 1 Complex [eEF1A]) all have the same primary and critical function to shuttle aminoacylated tRNAs to the ribosome during protein translation. A codon–anticodon system ensures that the correct amino acid is added to the growing protein chain, a process that consumes guanosine triphosphate (GTP) prior to releasing the elongation factor from the aminoacyl tRNA. However, bacteria and eukaryotes differ in the mechanism by which they recharge the elongation factor/guanosine diphosphate (GDP) complex. This recharging function is executed by the Elongation Factor Thermo stable (EF-Ts) in prokaryotes and by eukaryotic Elongation Factor 1B (eEF1B) in eukaryotes (Cacan et al., 2013) (Figure 1).

TABLE 1.

Elongation Factors in eukaryotes and their equivalent title in prokaryotes.

| Eukaryotic protein | Prokaryotic equivalent |

| eEF1/EF-1 | EF1/EF-T |

| eEF1A/(e)EF-1α | EF1A/EF-Tu |

| eEF1B/(e)EF-1β | EF1B/EF-Ts |

| eEF1Bβγδ (animals) 3 subunits | |

| eEF1Bαβγ (yeast) 2 subunits | |

| eEF1Bβγδ (plants) 3 subunits | |

| eEF2/EF-2 | EF2/EF-G |

| eEF3/EF-3 | N/A |

Both the new nomenclature and the old are shown below in the format of current/old. Although new nomenclature has been established for over a decade, many articles still use the old nomenclature. Indeed, the old nomenclature is more widely used in the prokaryotic literature and that is why EF1A is referred to as EF-Tu in this review. Adapted from Ejiri (2002) and Sasikumar et al. (2012).

FIGURE 1.

The canonical role of EF-Tu in translation. Structures sourced from protein databank (PDB), accession numbers 1DG1, 5OPD, 1B23, 4PC7, 1EFT, 1EFT. EF-Ts monomer structure obtained using Phyre2.

EF-Tu is comprised of three domains known as domains i, ii and iii which have evolved a high degree of molecular flexibility. To perform its canonical function, EF-Tu must form a functional binding pocket for an aminoacyl-tRNA, and to achieve this, domain i must become aligned more closely to domains ii and iii (i.e., they must move by around 90°) (Kjeldgaard et al., 1993). The extent of intramolecular movement needed to accommodate the aminoacyl-tRNA is about one third of the protein’s total diameter, indicating how significant this conformational change is (Sprinzl, 1994). Once the incoming aminoacyl-tRNA has docked with the mRNA, GTPase activity induces a reverse conformational change enabling the release of EF-Tu from the ribosome (Polekhina et al., 1996). The structural and functional constraints needed to execute these critical molecular interactions ensure that key domains within EF-Tu evolve slowly compared to molecules that perform their functions on the cell surface, where they face constant challenge from the host’s immunological defenses and undergo diversifying selection. As such, EF-Tu is considered to be an ancient molecule that is comprised of domains that are highly conserved in phylogenetically diverse prokaryotes (Filer and Furano, 1980). This sequence conservation extends to EF-Tu homologs in eukaryotes, which have also evolved a similar overall protein synthesis pathway (Ejiri, 2002).

Genetic Evolution of EF-Tu

In bacteria, EF-Tu is encoded by the tuf gene. tuf has a highly conserved genomic location and amino acid sequence, and has been used in the construction of phylogenetic trees for species discrimination (Iwabe et al., 1989; Baldauf et al., 1996; Mignard and Flandrois, 2007; Shin et al., 2009; Li et al., 2012; Caamano-Antelo et al., 2015). Amongst different bacterial species the EF-Tu sequences have less than 30% sequence divergence (Lathe and Bork, 2001). Low G + C Gram positive bacteria carry only a single copy of tuf (Ke et al., 2000). In contrast, many enteric bacteria have two copies (tufA and tufB) while three tuf-like genes have been identified in Streptomyces ramocissimus (Filer and Furano, 1981; Vijgenboom et al., 1994). In species with two copies of the gene, the two genes differ by less than 1.4%, based on nucleotide comparison (Lathe and Bork, 2001). In some bacteria with two copies of tuf, deletion of one copy of the gene is not lethal to the bacterium (Hughes, 1990; Zuurmond et al., 1999). It has been postulated that a second copy of this gene (which is mainly conserved in Gram negative bacteria) evolved before the branching of eubacteria (Lathe and Bork, 2001). The cause for the intermittent presence of the second copy of tuf within eubacteria has been debated. It has been proposed that the second copy arose by lateral gene transfer, at least within Enterococci (Ke et al., 2000), whilst others argue that lateral gene transfer is unlikely in translation factors and attribute the discontinuous observation of a second tuf gene to the theory that it had been randomly lost in some lineages (Lathe and Bork, 2001).

Eukaryotes have two isoforms of EF-Tu known as eEF1A1 and eEF1A2 (Table 1), with each sharing 96% amino acid similarity (Abbas et al., 2015). Both isoforms are also highly expressed representing 1–11% of the total protein expressed (Slobin, 1980; Abbas et al., 2015). Some cells express just one of the eEF1A isoforms, while both are expressed after muscle trauma and in some tumor cell types (Bosutti et al., 2007; Abbas et al., 2015). The number of genes encoding eEF1A varies widely within eukaryotes, from ten in maize to four in rice (Ejiri, 2002).

Moonlighting Proteins in Bacteria

There is now overwhelming evidence that proteins with canonical functions in the bacterial cytosol also perform important tasks on the bacterial cell surface (Sanchez et al., 2008; Kainulainen and Korhonen, 2014; Ebner and Götz, 2019). EF-Tu features prominently in many of these studies. Many moonlighting proteins are ancient, highly expressed enzymes, or are proteins that are perform essential roles in glycolysis, respiration and respond to stress (Henderson and Martin, 2011). There is evidence that only a subset of cytosolic proteins can traffic onto the cell because other highly expressed cytosolic proteins are not observed on the cell surface or in extracellular secretions (Vanden Bergh et al., 2013). Mass spectrometry studies have been instrumental in revealing the identities of surface accessible proteins that are not predicted to reside on the cell surface that have canonical functions in the bacterial cytosol (Jeffery, 2005; Robinson et al., 2013; Jarocki et al., 2015; Tacchi et al., 2016; Wang and Jeffery, 2016; Widjaja et al., 2017). The presence of surface-associated moonlighting proteins has been confirmed using florescence and electron microscopy (Bergmann et al., 2001; Candela et al., 2010; Yamaguchi et al., 2010; Robinson et al., 2013; Grundel et al., 2015; Jarocki et al., 2015). It is notable that purified, soluble moonlighting protein fails to associate with the surface when exogenously incubated with bacterial cells (Saad et al., 2009) suggesting that posttranslational modification(s) that occur in the host bacteria and/or passage through the cell membrane may be important events in a proteins ability to moonlight on the cell surface. Another unusual feature of protein moonlighting is that not all strains belonging to the same species present moonlighting proteins on their cell surface. For example, only a subset of pathogenic E. coli express surface GAPDH which binds host molecules (Egea et al., 2007). Finally, it is now known that moonlighting proteins are processed on the surface of bacterial pathogens. Processing is expected to increase protein disorder and alter function compared to the full length proteoform (Tacchi et al., 2016). Here we present key studies that describe the salient features that define the diverse moonlighting functions of EF-Tu related to pathogenesis (Figure 2 and Table 2).

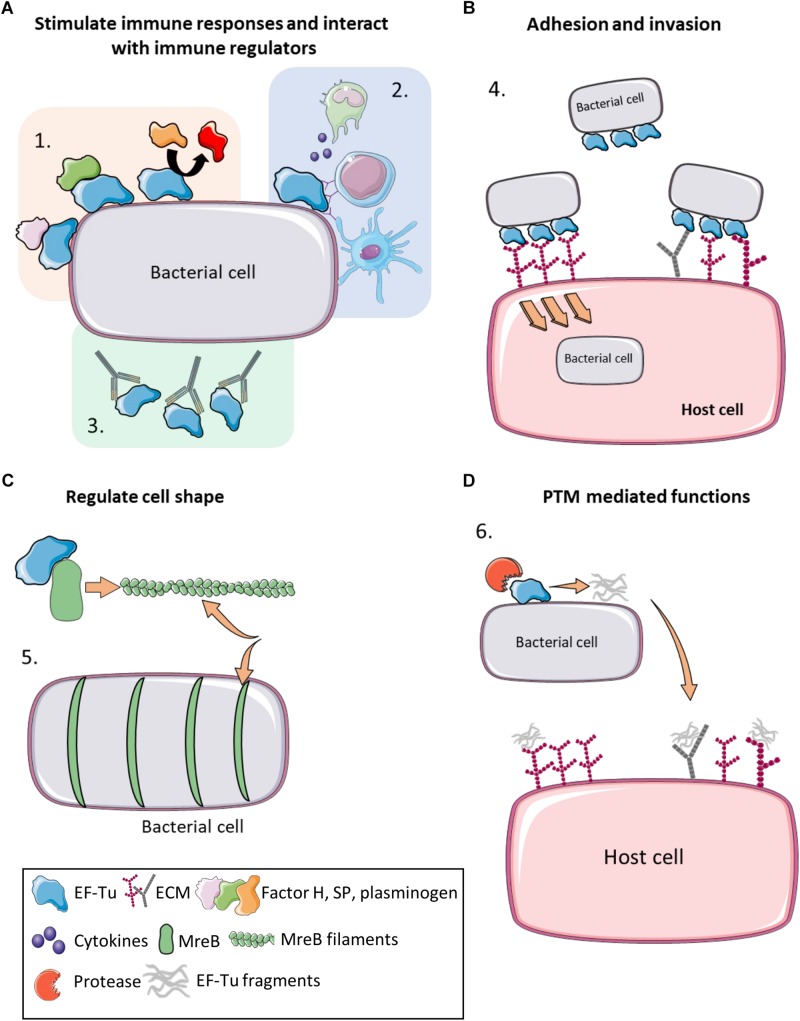

FIGURE 2.

Moonlighting functions of prokaryote EF-Tu. (A) (1) EF-Tu binds immune system regulators such as Factor H, substance P and plasminogen (and enhancing its conversion to plasmin), increasing virulence and immune system evasion. (2) EF-Tu stimulates both host innate and humoral immune responses. (3) Antibodies against EF-Tu decrease bacterial load and offer at least partial protection against some bacterial infections. (B) (4) EF-Tu binding to fibronectin facilitates invasion into host cells. EF-Tu also binds to other extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins, such as glycosaminoglycans, facilitating adhesion. (C) (5) EF-Tu binds MreB and facilitates production of MreB filaments that regulate cell shape. (D) (6) EF-Tu undergoes proteolytic processing and EF-Tu fragments also bind ECM proteins. Furthermore, these fragments may act as molecular decoys to help evade immune detection.

TABLE 2.

List of moonlighting functions published for EF-Tu in prokaryotes.

| Species | Moonlighting function | Year | References |

| Acidovorax avenae | Rice plants recognize the central amino acids (175-225aa) of EF-Tu as a PAMP | 2014 | Furukawa et al., 2014 |

| Acinetobacter baumannii | Binds fibronectin Binds plasminogen |

2012 2015 |

Dallo et al., 2012 Koenigs et al., 2015 |

| Actinobacillus seminis | Binds fibrinogen and fibronectin | 2018 | Montes-García et al., 2018 |

| Bacillus anthracis | Binds plasminogen to evade C3b-dependent innate immunity | 2011 | Chung et al., 2011 |

| Bacillus cereus | Target for Substance P (SP) | 2013 2019 |

Mijouin et al., 2013 N’Diaye et al., 2019 |

| Bacillus subtilis | Binds calcium ions Role in cell shape maintenance, colocalizes and modulates MreB filament formation |

2009 2010 2015 |

Dominguez et al., 2009 Defeu Soufo et al., 2010, 2015 |

| Escherichia coli | Cleaved in response to phage infection inducing phage exclusion induction Arabidopsis thaliana recognizes the first 18 aa of EF-Tu as a PAMP Interacts and modulates MreB filament formation Interacts with DsbA |

1994 1998 2000 2004 2005 2014 |

Bingham et al., 2000 Georgiou et al., 1998 Yu and Snyder, 1994 Kunze et al., 2004 Butland et al., 2005 Premkumar et al., 2014 |

| Francisella tularensis | Interacts with THP-1 nucleolin | 2008 | Barel et al., 2008 |

| Gallibacterium anatis | Forms filaments, binds fibronectin and fibrinogen | 2017 | López-Ochoa et al., 2017 |

| Helicobacter pylori | Adheres to THP-1 cells, novel potential adhesion factor | 2016 | Chiu et al., 2016 |

| Klebsiella pneumonia | Virulence factor for Leukopenia caused by Klebsiella pneumonia | 2014 | Liu et al., 2014 |

| Lactobacillus johnsonii | Attachment to human intestinal cells and mucins, and participates in host immunomodulation (IL-8 production) | 2004 | Granato et al., 2004 |

| Lactobacillus delbrueckii | Binds mucin | 2013 | Dhanani and Bagchi, 2013 |

| Lactobacillus paraplantarum | Modulates biofilm formation | 2017 | Liu et al., 2017 |

| Lactobacillus plantarum | Adheres to Caco-2 cells Binds mucin Binds actin |

2008 2011 2013 2018 |

Ramiah et al., 2008 Dhanani et al., 2011 Dhanani and Bagchi, 2013 Peng et al., 2018 |

| Leptospira interrogans serovar Copenhageni | Binds Factor H and plasminogen (and other ECM) | 2013 | Wolff et al., 2013 |

| Listeria monocytogenes | Binds plasminogen Induces dendritic cell maturation |

2004 2016 |

Schaumburg et al., 2004,Mirzaei et al., 2016 |

| Mycobacterium avium subsp. Paratuberculosis | Binds fibronectin | 2014 | Viale et al., 2014 |

| Mycoplasma fermentans | Interacts with the intracytoplasmic domain of CD21 (EBV/C3d receptor) | 2005 | Balbo et al., 2005 |

| Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae | Fragments bind heparin and fibronectin Binds A594 cells, fetuin, actin, heparin, and plasminogen Binds fibronectin |

2016 2017 2018 |

Tacchi et al., 2016 Widjaja et al., 2017 Yu et al., 2018 |

| Mycoplasma pneumoniae | Binds fibronectin Binds A594 cells, fetuin, actin, heparin, and plasminogen | 2002 2008 2017 |

Dallo et al., 2002 Balasubramanian et al., 2008 Widjaja et al., 2017 |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | Binds Factor H and plasminogen Trimethylation of the lysine allowing binding to platelet-activating receptor Part of the TVISS |

2007 2013 2015 |

Kunert et al., 2007 Barbier et al., 2013 Whitney et al., 2015 |

| Staphylococcus aureus | Target for Substance P (SP) | 2016 | N’Diaye et al., 2016 |

| Staphylococcus epidermidis | Target for Substance P (SP) | 2016 | N’Diaye et al., 2016 |

| Streptococcus gordonii | Binds saliva mucin MUC7 | 2009 | Kesimer et al., 2009 |

| Streptococcus pneumoniae | Binds Factor H, FHL-1, CFHR1 and plasminogen | 2014 | Mohan et al., 2014 |

Table is arranged based on function, showing different species have evolved the same EF-Tu moonlighting functions. The majority of these moonlighting functions have only been described in the last decade.

EF-Tu Is Exposed on the Surface of Bacteria

EF-Tu was first described as having a moonlighting function on the cell surface of M. pneumoniae (Dallo et al., 2002). As EF-Tu has now been found on the surface of a wide range of prokaryotes (Table 3), the potential mechanisms behind its extracellular locale shall be summarized here.

TABLE 3.

Literature reporting the identification of bacterial EF-Tu in non-cytoplasmic locations.

Articles searched between 2014–2018 identified EF-Tu present on the surface†or in secretions of many bacterial species. Antibodies to this protein were also identified in a number of studies. This table includes data from accessible Supplementary Files. Key search terms used were, but not limited to: exoproteome, secretome, surfacome, surfaceome, immunoproteome, and secretomic. Table excludes any data that was only bioinformatically determined. †Includes surfacome, outer membrane, specific protein analysis under any condition.

Typically, newly synthesized proteins destined for the cell surface possess either signal peptides or signal motifs that are recognized by transport machinery and translocated through the cytoplasmic membrane (Green and Mecsas, 2016). However, conventionally cytosolic proteins lacking signal sequences, like EF-Tu, have also been identified extracellularly. These proteins, termed non-classically secreted proteins (Wang et al., 2016), can be differentiated from other cytosolic proteins by assessing properties such as amino acid composition and structurally disordered regions (Bendtsen et al., 2005). Indeed, EF-Tu was one protein used to construct the feature-based non-classically secreted protein prediction software SecretomeP (Bendtsen et al., 2005). However, the actual mechanisms behind non-classical protein secretion remain a topic for debate. While there are translocation systems that do not require signal peptides, such as the Holin–Antiholin system, ABC transporters, and a type seven secretion system in Gram-positive bacteria (Götz et al., 2015), these only account for a small portion of non-classically secreted proteins (Wang et al., 2016). Therefore, the presence of cytosolic proteins in extracellular locations is often linked with cell lysis.

There is evidence supporting cytosolic protein excretion through cell lysis, and there is evidence supporting excretion through alternative secretion pathways (reviewed in Wang et al., 2013a). In addition to specific secretion pathways, cytosolic protein excretion can also occur through compromised membrane integrity, translational and osmotic stress, the protein’s biochemical and structural properties, and via membrane vesicles (MVs) (Outer Membrane Vesicles [OMVs] in Gram-negative bacteria) (reviewed in Ebner and Götz, 2019).

Multiple mechanism may contribute to the surface location of EF-Tu; however, there are substantial reports of MVs carrying EF-Tu. Bacterial MVs are nanoparticles produced through processes such as membrane blebbing and endolysin-triggered cell death and contain various membrane and cytosolic proteins, as well as lipopolysaccharides, peptidoglycan and DNA (Turnbull et al., 2016; Toyofuku et al., 2019). MVs are involved in diverse biological processes, including virulence, biofilm development, quorum sensing, horizontal gene transfer, and exportation of cellular components (Toyofuku et al., 2019). EF-Tu is present within MVs derived from Gram-positive bacteria including Listeria monocytogenes (Coelho et al., 2019), Mycobacterium bovis, Mycobacterium smegmatis, Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Prados-Rosales et al., 2011), Staphylococcus aureus (Lee et al., 2009; Wang et al., 2018), Streptococcus agalactiae (Surve et al., 2016), Streptococcus pnuemoniae (Olaya-Abril et al., 2014), and Streptococcus pyogenes (Resch et al., 2016); Gram-negative bacteria including Acinetobacter baumannii (Kwon et al., 2009), Bacteroides fragilis (Zakharzhevskaya et al., 2017), Cronobacter sakazakii (Alzahrani et al., 2015), Escherichia coli (Lee et al., 2007), Francisella novicida (Pierson et al., 2011), Haemophilus influenzae (Sharpe et al., 2011), Klebsiella pneumoniae (Lee et al., 2012), Neisseria gonorrhoeae (Pérez-Cruz et al., 2015), Neisseria meningitidis (Vipond et al., 2006), and Pseudomonas aeruginosa (Choi et al., 2011); and in six Mycoplasma species (Gaurivaud et al., 2018). Indeed, EF-Tu was reported as one of the most abundant protein in some of these studies (Lee et al., 2009; Pérez-Cruz et al., 2015; Gaurivaud et al., 2018). Interestingly, several MVs that contain EF-Tu have been reported to increase virulence (Surve et al., 2016), modulate immune responses (Prados-Rosales et al., 2011; Sharpe et al., 2011; Alzahrani et al., 2015), and offer protection to infection via immunization (Vipond et al., 2006; Pierson et al., 2011; Olaya-Abril et al., 2014). As the number of MV-encapsulated proteins varied dramatically within this subset of studies, ranging from 8 in S. agalactiae to 416 in F. novicida, it is not possible to determine the exact role EF-Tu plays in these processes in most instances. However, in the case of S. pneumoniae MVs, which were shown to have high immunogenic capacity and induce protective responses in mice, EF-Tu was one of 15/161 MV proteins that were immunogenic and one of two proteins from which antibodies were generated against in immunized mice (Olaya-Abril et al., 2014).

EF-Tu Stimulates a Humoral Immune Response and Interacts With Host Immune Regulators

Antibodies against EF-Tu have also been detected in a range of natural infections, including those caused by Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae (Pinto et al., 2007), Chlamydia trachomatis (Sanchez-Campillo et al., 1999) and K. pneumonia (Liu et al., 2014). Recombinant EF-Tu (rEF-Tu) from Mycoplasma ovipneumoniae induces an immune response in mice, increasing levels of IgG, TNF-α, IFN-γ, IL-12(p70), IL-4, IL-5, and IL-6. Sera from mice immunized with rEF-Tu also reduced M. ovipneumoniae growth (Jiang et al., 2016). In Mycoplasma fermentans, EF-Tu interacts specifically with the C-terminal 34 amino acids of CD21 in human B lymphoma cells (Balbo et al., 2005). CD21 receptors on the B cells enable the complement system to influence B-cell activation and maturation. The implication is that Mycoplasma species are involved in malignancies (reviewed in Vande Voorde et al., 2014) and the interaction between EF-Tu and CD21 may be significant in this regard. EF-Tu from L. monocytogenes is the main activator of host dendritic cells (DC) (Mirzaei et al., 2016), antigen presenting cells (APCs) that play a key role in host immune modulation. Activation of DCs is achieved when L. monocytogenes interacts with the pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) on the surface of DCs (Mirzaei et al., 2016). These PRRs recognize bacterial proteins known as PAMPS (pathogen-associated molecular pattern). In L. monocytogenes EF-Tu was identified as a potent immuno-stimulatory effector in this process indicating that EF-Tu is a candidate for DC maturation-based therapies (Mirzaei et al., 2016).

Recombinant EF-Tu (rEF-Tu) has recently shown promising results as a vaccine candidate against bacterial pathogens. Immunization with rEF-Tu elicited both Th1 and Th2-type responses against Streptococcus suis and anti-rEF-Tu sera reduced viable load detection in porcine blood (Feng et al., 2018). Mice immunized with rEF-Tu demonstrated significant protection against lethal challenges with S. pneumoniae and increased cytokine, IgG1 and IgG2a, and CD4+ T-cell production (Nagai et al., 2019). rEF-Tu mediated protection against S. pneumoniae has also been demonstrated in fish (Yang et al., 2018), and partial protection against H. influenzae was achieved in mice (Thofte et al., 2018).

Besides stimulating an immune response in mammals (Figure 2A), EF-Tu is also a recognized PAMP in plants (Kunze et al., 2004; Furukawa et al., 2014). EF-Tu is secreted by via unknown mechanisms in soil dwelling, plant–pathogenic bacteria and is recognized by membrane-associated PRRs found on the extracellular surface of root epithelial cells in different plant species. The interaction between PRRs and PAMPS identifies the bacteria as an infectious threat, triggering a signal transduction cascade, that elicits an innate immune response (Zipfel, 2008) that includes the production of reactive-oxygen species and programed cell death (Zipfel, 2008).

Both monocots and dicots use EF-Tu to notify their immune system of an infection. There is however, another level of sophistication to this interaction (Furukawa et al., 2014). Different plant species are known to have evolved recognition mechanisms in their respective PRRs that interact with different regions in the EF-Tu molecule. Rice PRRs recognize the amino acids (aa) 175-225 of EF-Tu, termed EFa50, from the plant pathogenic bacteria Acidovorax citrulli (formerly Acidovorax avenae) (Furukawa et al., 2014) whereas Arabidopsis thaliana recognizes the first 18 aa of EF-Tu from E. coli (termed elf18) (Kunze et al., 2004). Although elf18 does not illicit a response to this pathogen in rice plants, engineering the Arabidopsis PRR for elf18 into the rice plant enabled rice to recognize elf18 and respond by increasing resistance to bacterial attack (Lu et al., 2015). This proof-of-concept experiment demonstrated that PRRs can to be engineered into the genomes of different crop species and may be beneficial to the farming and food production industry. Transfer of PRRs has already been demonstrated on food crops such as tomatoes and wheat (Lacombe et al., 2010; Schoonbeek et al., 2015). Earlier structural studies of EF-Tu suggested that the first 12 amino acids of EF-Tu are exposed on the surface and the dodecapeptide can act as a competitive inhibitor of the elf18 elicitor (Kunze et al., 2004). The first 12aa of EF-Tu can also suppress the apoptotic response in plant cells allowing bacterial pathogens sufficient time and nutrient resources to colonize and replicate within plant cells (Igarashi et al., 2013). elf18 and EFa50 do not seem to have similar properties, but more recent structural studies have shown that they do appear to be (at least partially) surface exposed on the EF-Tu molecule (Furukawa et al., 2014). These data indicate that these two PAMPS can interact with PRRs on plant cell surfaces.

EF-Tu has also been shown to bind selectively to neuropeptide hormone substance P (SP) (Mijouin et al., 2013; N’Diaye et al., 2016). SP belongs to the tachykinin family of neuropeptides released by nerve and inflammatory cells (Datar et al., 2004) and is linked to many inflammatory diseases because it binds to the neurokinin 1 receptor (NK-1R) which stimulates pro-inflammatory responses (O’Connor et al., 2004). The inability to trigger NK-1R decreases bacterial clearance and increases death rates in mouse models of infection (Verdrengh and Tarkowski, 2008). SP and/or NK-1R have been linked to disease caused by infectious agents (Douglas et al., 2001; Schwartz et al., 2013), autoimmune disorders (Mantyh et al., 1988), psychological disturbances (Fehder et al., 1997; Herpfer and Lieb, 2005; McLean, 2005; Ebner and Singewald, 2006; Carpenter et al., 2008), cancer (Esteban et al., 2006), atopic dermatitis (Toyoda et al., 2002), and cell proliferation (Goode et al., 2003). EF-Tu from S. aureus, S. epidermidis, and B. cereus has been shown to bind SP, with an associated increase in virulence and biofilm formation (Mijouin et al., 2013; N’Diaye et al., 2016).

rEF-Tu derived from Lactobacillus johnsonii triggers a pro-inflammatory response in HT29 cells and increased IL-8 secretion in the presence of CD14 (Granato et al., 2004). IL-8 is known to increase levels of calcium ions within the cell in which it is expressed (Tuschil et al., 1992; Schorr et al., 1999). In Bacillus subtilis EF-Tu is a calcium binding protein (Dominguez et al., 2009). However, the link between calcium and EF-Tu in prokaryotes remains tenuous and further studies are needed to investigate the voracity of this association and its implication in the inflammatory response.

EF-Tu Has a Role in Adherence to Host Molecules

Infection

Adhesion to host cells and molecules is fundamental to pathogenesis in many bacterial species as it facilitates colonization, invasion, and host immune subversion (Stones and Krachler, 2016). In many instances, moonlighting functions for EF-Tu are associated with a role in adherence to a range of host molecules and host cells (Figure 2B). This does not appear to be a trend in specific phylogenetic groups of prokaryotes, as it extends through a range of bacteria. EF-Tu resides on the surface of Francisella tularensis where it binds to the RGG domain of nucleolin on the surface of the human monocytic cell line THP-1 (Barel et al., 2008). The HB-19 pseudopeptide irreversibly binds to the RGG domain in the C-terminus of nucleolin (Nisole et al., 1999, 2002) and effectively blocks attachment of Francisella tularensis (Barel et al., 2008). Consistent with these experiments, EF-Tu and a 32 kDa cleavage fragment of EF-Tu were recovered during affinity chromatography pull-down experiments using nucleolin as bait (Barel et al., 2008). It is notable that cleavage fragments of EF-Tu have been previously described in the cytoplasm and membrane fraction of L. monocytogenes (Archambaud et al., 2005) and more recently on the extracellular surfaces of S. aureus, Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae and M. pneumoniae (Widjaja et al., 2015, 2017). Despite this finding, data describing the cleavage products in L. monocytogenes has not been reported but is an interesting observation nonetheless that warrants further investigation.

Fibronectin (Fn) is a key component of the extracellular matrix. It is a glycoprotein that binds to integrins embedded in eukaryote cell membranes and provides support and anchors cells to substrata. Many bacterial pathogens and commensals express adhesins that bind Fn and these interactions can trigger cytoskeletal rearrangements that promote host cell invasion (Massey et al., 2001; Deutscher et al., 2010; Seymour et al., 2010, 2012; Henderson et al., 2011; Bogema et al., 2012; Raymond et al., 2015, 2018). Interestingly, Fn also plays a role as a signaling molecule so, binding Fn may serve other functions for the bacteria, compounding their infectivity (Sandig et al., 2009). Indeed, many bacteria have a repertoire of dedicated, secreted adhesins that target Fn (Henderson et al., 2011).

EF-Tu localizes to both the outer membrane (OM) and outer membrane vesicles (OMV) of A. baumannii and binds to DsbA (Premkumar et al., 2014), a protein important in protein folding and maturation (Heras et al., 2009). In its external location in A. baumannii EF-Tu directly binds Fn (Dallo et al., 2012). The genome-reduced, human pathogen, M. pneumoniae also displays EF-Tu on its cell surface and plays an important role in interactions with Fn (Dallo et al., 2002; Widjaja et al., 2017). Anti-EF-Tu antibodies are able to prevent the binding of M. pneumoniae to immobilized Fn demonstrating the specificity of this interaction (Dallo et al., 2002). Binding of EF-Tu is confined to the C-terminal region of EF-Tu, with two Fn-binding regions being identified at amino acid positions 192-292 and 314-394 (Balasubramanian et al., 2008). The specificity of the Fn binding domain between amino acids 314-394 was confirmed when peptides spanning this region blocked the binding capacity of EF-Tu to Fn by 62% (Balasubramanian et al., 2009). Notably, EF-Tu from Mycoplasma genitalium, which shares 96% identity with EF-Tu from M. pneumoniae, does not bind Fn (Balasubramanian et al., 2009). Experimental comparison between the two sequences identified the residues S343, P345 and T357 to be key in the interaction with Fn (Balasubramanian et al., 2009). However, the Fn-binding A. baumannii EF-Tu does not possess these key binding residues identified in M. pneumoniae (see Supplementary File), suggesting an alternative Fn-binding mechanism. More recently, we have shown that EF-Tu from M. pneumoniae is a multifunctional, adhesive moonlighting protein that can bind fetuin, heparin, actin, as well as to plasminogen, vitronectin, lactoferrin, laminin, and fibrinogen (Widjaja et al., 2017).

The exogenous addition of soluble Fn is known to promote the ability of Mycobacterium avium subsp. paratuberculosis to attach and invade two epithelial cell lines (Secott et al., 2002) but the identity of bacterial cell surface receptor(s) for Fn were not known. EF-Tu is a surface exposed cell wall protein in Mycobacterium avium subspecies paratuberculosis (MAP) (Viale et al., 2014). With the importance of Fn to MAP adhesion and invasion (Secott et al., 2002), and as EF-Tu is known to bind Fn in M. pneumoniae (Dallo et al., 2002; Balasubramanian et al., 2008) and A. baumannii (Dallo et al., 2012), it was investigated for its role as a Fn-binding protein. Knowledge of the Fn-binding regions of EF-Tu from M. pneumoniae was used to map putative Fn-binding regions in EF-Tu from A. baumannii (Dallo et al., 2012). Although the two previously identified Fn-binding regions (Balasubramanian et al., 2008) only showed 73 and 69% identity respectively in the EF-Tu homolog from MAP, ELISA assays showed that MAP EF-Tu binds Fn in a dose-dependent manner (Viale et al., 2014).

EF-Tu binds to human intestinal cells and mucins in a pH-dependent manner in the probiotic bacterium, Lactobacillus johnsonii suggesting a role for EF-Tu in gut colonization (Granato et al., 2004). At pH 5, EF-Tu derived from L. johnsonii was able to bind to the human colorectal adenocarcinoma cell line HT29 cells, undifferentiated CACO-2 cells and mucins isolated from HT29-MTX cells (Granato et al., 2004). The ability of EF-Tu to bind mucins extends to other anatomical locations, including the saliva mucin, MUC7 (Kesimer et al., 2009). EF-Tu was identified as one of six proteins to bind this mucin in Streptococcus gordonii, a major oral colonizer (Kesimer et al., 2009).

When H. pylori is co-cultured with THP-1 cells, expression of EF-Tu is upregulated and secreted and shown to localize to the surface of the human monocytic cell line THP-1 implicating it in host adhesion (Chiu et al., 2016).

While there are currently no universal moonlighting motifs (Babady et al., 2007), basic residues, both singularly and in clusters, are known to be binding anchors for anionic glycosaminoglycans (Jayaraman et al., 2000), are key in plasminogen (Jarocki et al., 2015), DNA (Ruyechan and Olson, 1992) and actin-binding (Peng et al., 2018), and have been linked with biofilm formation (Shanks et al., 2005; Green et al., 2013). Such basic residue clusters are found throughout the sequences of EF-Tus with reported moonlighting functions (Figure 3 and Supplementary File).

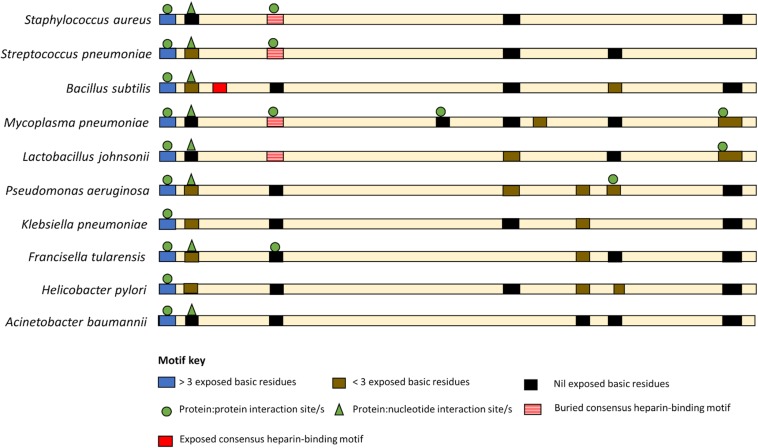

FIGURE 3.

Basic amino acid residue clusters that reside within EF-Tu molecules that moonlight in prokaryotes. An exposed basic amino acid cluster (blue bar) with a putative P:P interaction sites (green circle) is present at the N-termini of moonlighting EF-Tu examples from both Gram positive and Gram-negative bacteria. However, only the Gram-positive bacteria appear to have a consensus heparin binding motif (red bar) and only in B. subtilis is this motif predicted to be solvent accessible (solid red bar). The remaining basic residue clusters are predicted to be at least partial buried.

A basic residue cluster is located at the N-termini of EF-Tu molecules with known moonlighting functions (Figure 3 and Table 2). This short linear motif (SLiM) has at least three surface exposed basic residues, resides within a region of protein disorder, and possesses predicted protein:protein interaction sites. The arginine and lysine residues in positions 7 and 9 are unconserved in some bacterial species, thus may have arisen from advantageous point mutations (Figure 4).

FIGURE 4.

N-termini basic residue cluster logo. The logo is representative of EF-Tu molecules derived from 17 prokaryote species.

Interestingly, the moonlighting EF-Tu from Mycoplasma fermentans has a unique, highly surface exposed, N-terminal extension that is 39 amino acids in length and possess an additional basic residue cluster at 31nKmKgKy38 (see Supplementary File). Whether M. fermentans EF-Tu harbors moonlighting adhesive capabilities is currently unknown and may warrant future investigation.

Apart from the N-termini, the remaining basic residue clusters observed in EF-Tu molecules that moonlight are at least partially buried, which may impede their ability to bind host molecules. However selective cell surface proteolysis, described in detail in Section “Post-translational Modifications of EF-Tu,” can overcome some of the structural impediments.

EF-Tu Binds Innate Immune Effectors

Many bacterial pathogens of medical (Sanderson-Smith et al., 2012) and veterinary (Raymond and Djordjevic, 2015) significance have the ability to bind and activate plasminogen, a process that relies on interactions between basic amino acid residues on surface-accessible bacterial adhesins and kringle domains in plasminogen (Figure 2A). EF-Tu is also utilized by bacteria to dampen the host immune response. The ability of EF-Tu to bind to host complement factors and plasminogen has been demonstrated in Pseudomonas aeruginosa (Kunert et al., 2007), Leptospira sp. (Wolff et al., 2013), Streptococcus pneumoniae (Mohan et al., 2014) M. pneumoniae (plasminogen only) (Widjaja et al., 2017) and Acinetobacter baumannii (plasminogen only) (Koenigs et al., 2015). The complement system is part of the innate immune system which non-specifically acts to clear the body of infection by lysing bacteria (Lambris et al., 2008). Complement factors bound on the bacterial surface remain active, and plasminogen can be converted to plasmin in its bound state (Kunert et al., 2007; Wolff et al., 2013; Mohan et al., 2014; Raymond and Djordjevic, 2015). This allows the bacteria to regulate and utilize these components for their own gain. By recruiting FH, FH1 and plasminogen the bacteria are able to inactivate C3b via a cleavage event mediated by FH, FH1 and plasmin (Lambris et al., 2008). The C3b complement factor is an important opsonization trigger that binds and labels bacteria ready for opsonization by the host immune system (Lambris et al., 2008). By degrading C3b, the bacteria are able to overcome this aspect of the innate immune system (Lambris et al., 2008). Additionally, the recruitment of plasmin to the bacterial cell surface plays an important role in degrading ECM and facilitating tissue invasion (Lahteenmaki et al., 2000; Bhattacharya et al., 2012). By binding complement factors such as Factor-H, FHL-1 and CFHR1 the bacterium is able to suppress this process and evade the host innate immune response.

Bacterial infections can also lead to a reduction in white blood cell (WBC) counts in infected hosts leading to leukopenia. Isolates of K. pneumoniae from patients with leukopenia express higher levels of EF-Tu compared with K. pneumoniae isolates from patients with leucocytosis (Liu et al., 2014) suggesting that EF-Tu may be a pathogenicity factor in K. pneumonia-based leukopenia (Liu et al., 2014). Interestingly, EF-Tu is upregulated in Mycobacterium species that have been phagocytosed by macrophages. The purpose of this upregulation has yet to be determined, but may further support the idea of a role for EF-Tu in bacterial evasion of the host immune system (Monahan et al., 2001).

Not only do bacteria have to defend themselves against the host immune response, but often they must defend themselves against each other. Due to the competitive environment in which bacteria live, they have developed toxins that target other bacterial cells. The Type VI secretion system (T6SS) can deliver toxin molecules into the cytosol of competing bacteria inhabiting the same niche (Pukatzki et al., 2006; Coulthurst, 2013; Cianfanelli et al., 2016). For the T6SS effector molecule in P. aeruginosa to enact its toxic effect, it must interact with EF-Tu prior to delivery into the recipient’s cytoplasm (Whitney et al., 2015). The effector molecule and EF-Tu directly bind to each other in members of the Pseudomonas genus (Whitney et al., 2015). These observations suggest that EF-Tu has a wide variety of moonlighting functions relating to pathogenesis in different prokaryote species.

Cell Shape

Some bacteria can change cell shape as a protective strategy against the immune system. By changing shape, bacteria can become less easily engulfed by phagocytes, and can enhance biofilm formation thereby increasing persistence in the host (van Teeseling et al., 2017). Moreover, major actin-like cytoskeletal proteins, such as MreB, have a role in virulence. For example, in P. aeruginosa MreB regulates the type IV pili assemblage (Cowles and Gitai, 2010); in H. pylori MreB regulates the secretion of virulence factors (Waidner et al., 2009); and in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium a disruption in the mreB gene led to downregulation of genes involved in pathogenicity (Bulmer et al., 2012; Doble et al., 2012).

The hypothesis that EF-Tu may interact with the cytoskeleton in prokaryotes is not a new idea, with the concept being introduced as early as the 1970s when EF-Tu was shown to form filaments (Beck, 1979). More recently, the formation of amyloid-like filaments by Gallibacterium anatis EF-Tu has been linked to biofilm formation (López-Ochoa et al., 2017). EF-Tu also interacts with MreB in E. coli (Butland et al., 2005). MreB forms helical filaments beneath the cell membrane and is essential for regulating cell shape (Jones et al., 2001). As it is well known that eukaryotic EF-Tu (eEF1A) interacts with actin, and influences cell shape, it is conceivable that this moonlighting function also occurs in prokaryotes. In B. subtilis and E. coli (Defeu Soufo et al., 2010, 2015), EF-Tu modulates the formation of MreB filaments by binding MreB in a ratio of 1:1 (Defeu Soufo et al., 2015) (Figure 2C). One hypothesis suggests a link between EF-Tu cell concentration and cytoskeletal function. By reducing the expression of EF-Tu in the cell, cell shape can be modulated from the typical rod-like appearance to an abnormal cell shape (Defeu Soufo et al., 2010). Alteration of cell shape is due to disruption of the process that places MreB in helical structures beneath the membrane (Defeu Soufo et al., 2010). Further studies investigated whether EF-Tu’s role in the translation mechanism was directly related to the population of EF-Tu molecules that interact with MreB, or whether separate populations of EF-Tu are generated for these alternate roles. Treatment of bacterial cells with kirromycin, which inhibits the release of EF-Tu from the ribosome, failed to interfere with EF-Tu localization in the cytoskeleton or its interactions with MreB filaments (Defeu Soufo et al., 2010). As previous studies have only revealed an interaction between tufB with mreB (not tufA) (Butland et al., 2005), it is tantalizing to consider whether only one of the tuf genes is responsible for the alternate function of cytoskeletal integrity. This might suggest that evolution of two tuf genes is useful in the delegation of EF-Tu moonlighting roles.

Post-translational Modifications of EF-Tu

Proteolytic processing is an irreversible post-translational modification (PTM) that can result in a loss, gain or change of function in a protein, as well as in degradation (Turk, 2006). Processing may be a mechanism to unlock moonlighting functions that are inherent in the newly created cleavage fragments via a mechanism similar to ectodomain shedding (Raymond et al., 2013; Tacchi et al., 2016) (Figure 2D). Furthermore, cleavage fragments may serve as competitive inhibitors to host immune cells. Host cytokines, chemokines, enzymes, antimicrobial peptides and growth factors all bind ECM components, including heparin and fibronectin, to control immune responses such as leukocyte emigration through tissue (Gill et al., 2010). By binding to the same ligands as host effector molecules (Kaneider et al., 2007; Krachler and Orth, 2013), bacterial proteins and their cleavage fragments may dampen an immune response. Additionally, cleavage may result in the loss of antigenic epitopes in surface proteins thereby circumventing host immune detection.

Cell surface EF-Tu is proteolytically processed in M. hyopneumoniae (Tacchi et al., 2016; Berry et al., 2017; Widjaja et al., 2017). Cleavage fragments of EF-Tu are retained on the cell surface and recovered during affinity chromatography using different host molecules as bait (Tacchi et al., 2016). The cleavage of EF-Tu has recently been demonstrated to be more widespread than previously appreciated with cleavage sites now also mapped in the M. pneumoniae and S. aureus (Scherl et al., 2005; Plikat et al., 2007; Widjaja et al., 2017). Processing generates fragments that are predicted to be more structural disordered and exposes regions of EF-Tu that are normally inaccessible to the aqueous environment. In particular we have shown that novel SLiMs enriched in positive charges are exposed allowing them to bind to a range of host molecules (Widjaja et al., 2017). Processing has so far been described in bacteria that belong to the low G + C Firmicutes. Many protein:protein and protein:nucleic acid interactions require correctly spaced positive charges derived from lysine, arginine and histidine side chains in short regions of peptide sequence. Amino acids with positively charged side chain residues are encoded by A:T rich triplet codons and members of the low G + C Firmicutes are well suited to employ this as a strategy to expand their functional proteome. Single amino acid substitutions caused by single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) have previously been described as pathogenicity-enhancing (Weissman et al., 2003). Specifically, SNPs in E. coli and S. typhimurium adhesin genes have led to distinctive pathogenicity-enhanced phenotypes (Sokurenko et al., 1998; Pouttu et al., 1999; Boddicker et al., 2002). SNPs can provide bacteria a selective advantage, leading to niche expansion and ultimately, novel species (Weissman et al., 2003). We propose that the accumulation of positively charged residues via SNPs in SLiMs facilitates binding interactions with diverse host molecules (Widjaja et al., 2017). Processing presents a mechanism to release fragments, each with the potential to expose a different repertoire of SLiMS to the aqueous environment compared with the parent molecule, and generate protein multifunctionality (Widjaja et al., 2017).

Bacterial EF-Tus are also the target for reversible PTMs such as phosphorylation, methylation and acetylation. Phosphorylation of EF-Tu has been identified in E. coli (Lippmann et al., 1993), Thermus thermophiles (Lippmann et al., 1993), B. subtilis (Levine et al., 2006), Corynebacterium glutamicum (Bendt et al., 2003), Streptomyces collinus (Mikulik and Zhulanova, 1995), Thiobacillus ferrooxidans (Seeger et al., 1996), S. pneumoniae (Sun et al., 2010), M. genitalium (Su et al., 2007), and M. pneumoniae (Su et al., 2007). While phosphorylation of EF-Tu lowers its binding affinity to GTP, subsequently reducing protein synthesis, the PTM also inhibits binding by the antibiotic kirromycin, a specific inhibitor of EF-Tu (Archambaud et al., 2005; Sajid et al., 2011). Furthermore, the associated decreased bacterial growth facilitated by EF-Tu phosphorylation has been implicated as an acclimation measure to stress conditions during infection (Archambaud et al., 2005). Similarly, Van Noort et al. (1986) demonstrated that EF-Tu methylation in E. coli lowers GTP hydrolysis and suggest a more accurate translation process as a result.

Lysine acetylation and lysine glutarylation has been described in EF-Tu from Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Xie et al., 2015, 2016). These modifications can affect protein–protein and protein:nucleic acid interactions and it may be important to the pathogenicity of M. tuberculosis, although this is yet to be determined. Evidence for the role of PTMs in EF-Tu moonlighting functions have been described in P. aeruginosa, where the trimethylation of the lysine at residue 5, allows EF-Tu to structurally mimic phosphorylcholine (Barbier et al., 2013). This modification means that EF-Tu can specifically bind a platelet-activating receptor, resulting in successful bacterial adhesion (Barbier et al., 2013).

Concluding Remarks

EF-Tu has evolved to be a multifunctional protein in a wide variety of pathogenic bacteria. While moonlighting functions vary among microbial species there is a common theme for roles in adherence and in immune regulation. The understanding of how this essential and highly expressed protein evolved moonlighting functions is an active area of research and is likely that more diverse and important roles are yet to be discovered.

Author Contributions

KH and SD conceived and co-wrote the first draft with input from all authors for the final draft. VJ created the figures and contributed significantly to the revised manuscript. All authors contributed to revision, read and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Judith Pell for providing editorial assistance during the writing of this manuscript.

Footnotes

Funding. This work was supported by funds provided to SD from the University of Technology Sydney. Some of the authors were partly supported by funds from the Australian Centre for Genomic Epidemiological Microbiology (Ausgem), a collaborative partnership between the NSW Department of Primary Industries and the University of Technology Sydney.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmicb.2019.02351/full#supplementary-material

Amino acid sequence analysis of EF-Tus with moonlighting functions.

References

- Abbas W., Kumar A., Herbein G. (2015). The eEF1A proteins: at the crossroads of oncogenesis, apoptosis, and viral infections. Front. Oncol. 5:75. 10.3389/fonc.2015.00075 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altindis E., Dong T., Catalano C., Mekalanos J. (2015). Secretome analysis of Vibrio cholerae type VI secretion system reveals a new effector-immunity pair. mBio 6:e00075-15. 10.1128/mBio.00075-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alzahrani H., Winter J., Boocock D., De Girolamo L., Forsythe S. J. (2015). Characterization of outer membrane vesicles from a neonatal meningitic strain of Cronobacter sakazakii. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 362:fnv085. 10.1093/femsle/fnv085 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Archambaud C., Gouin E., Pizarro-Cerda J., Cossart P., Dussurget O. (2005). Translation elongation factor EF-Tu is a target for Stp, a serine-threonine phosphatase involved in virulence of Listeria monocytogenes. Mol. Microbiol. 56 383–396. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04551.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arntzen M. O., Karlskas I. L., Skaugen M., Eijsink V. G., Mathiesen G. (2015). Proteomic Investigation of the response of Enterococcus faecalis V583 when cultivated in urine. PLoS One 10:e0126694. 10.1371/journal.pone.0126694 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babady N. E., Pang Y.-P., Elpeleg O., Isaya G. (2007). Cryptic proteolytic activity of dihydrolipoamide dehydrogenase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104 6158–6163. 10.1073/pnas.0610618104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balasubramanian S., Kannan T. R., Baseman J. B. (2008). The surface-exposed carboxyl region of Mycoplasma pneumoniae elongation factor Tu interacts with fibronectin. Infect. Immun. 76 3116–3123. 10.1128/IAI.00173-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balasubramanian S., Kannan T. R., Hart P. J., Baseman J. B. (2009). Amino acid changes in elongation factor Tu of Mycoplasma pneumoniae and Mycoplasma genitalium influence fibronectin binding. Infect. Immun. 77 3533–3541. 10.1128/IAI.00081-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balbo M., Barel M., Lottin-Divoux S., Jean D., Frade R. (2005). Infection of human B lymphoma cells by Mycoplasma fermentans induces interaction of its elongation factor with the intracytoplasmic domain of Epstein-Barr virus receptor (gp140, EBV/C3dR, CR2, CD21). FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 249 359–366. 10.1016/j.femsle.2005.06.052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldauf S. L., Palmer J. D., Doolittle W. F. (1996). The root of the universal tree and the origin of eukaryotes based on elongation factor phylogeny. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 93 7749–7754. 10.1073/pnas.93.15.7749 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbier M., Owings J. P., Martinez-Ramos I., Damron F. H., Gomila R., Blazquez J., et al. (2013). Lysine trimethylation of EF-Tu mimics platelet-activating factor to initiate Pseudomonas aeruginosa pneumonia. mBio 4:e00207-13. 10.1128/mBio.00207-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barel M., Hovanessian A. G., Meibom K., Briand J. P., Dupuis M., Charbit A. (2008). A novel receptor - ligand pathway for entry of Francisella tularensis in monocyte-like THP-1 cells: interaction between surface nucleolin and bacterial elongation factor Tu. BMC Microbiol. 8:145. 10.1186/1471-2180-8-145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck B. D. (1979). Polymerization of the bacterial elongation factor for protein synthesis, EF-Tu. Eur. J. Biochem. 97 495–502. 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1979.tb13137.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bendt A. K., Burkovski A., Schaffer S., Bott M., Farwick M., Hermann T. (2003). Towards a phosphoproteome map of Corynebacterium glutamicum. Proteomics 3 1637–1646. 10.1002/pmic.200300494 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bendtsen J. D., Kiemer L., Fausbøll A., Brunak S. (2005). Non-classical protein secretion in bacteria. BMC Microbiol. 5:58. 10.1186/1471-2180-5-58 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergmann S., Rohde M., Chhatwal G. S., Hammerschmidt S. (2001). alpha-Enolase of Streptococcus pneumoniae is a plasmin(ogen)-binding protein displayed on the bacterial cell surface. Mol. Microbiol. 40 1273–1287. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02448.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berry I. J., Jarocki V. M., Tacchi J. L., Raymond B. B. A., Widjaja M., Padula M. P., et al. (2017). N-terminomics identifies widespread endoproteolysis and novel methionine excision in a genome-reduced bacterial pathogen. Sci. Rep. 7:11063. 10.1038/s41598-017-11296-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharya S., Ploplis V. A., Castellino F. J. (2012). Bacterial plasminogen receptors utilize host plasminogen system for effective invasion and dissemination. J. Biomed. Biotechnol. 2012:482096. 10.1155/2012/482096 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bingham R., Ekunwe S. I., Falk S., Snyder L., Kleanthous C. (2000). The major head protein of bacteriophage T4 binds specifically to elongation factor Tu. J. Biol. Chem. 275 23219–23226. 10.1074/jbc.M002546200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boddicker J. D., Ledeboer N. A., Jagnow J., Jones B. D., Clegg S. (2002). Differential binding to and biofilm formation on, HEp-2 cells by Salmonella enterica serovar typhimurium is dependent upon allelic variation in the fimH gene of the fim gene cluster. Mol. Microbiol. 45 1255–1265. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.03121.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogema D. R., Deutscher A. T., Woolley L. K., Seymour L. M., Raymond B. B. A., Tacchi J. L., et al. (2012). Characterization of cleavage events in the multifunctional cilium adhesin Mhp684 (P146) reveals a mechanism by which Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae regulates surface topography. mBio 3:e00282-11. 10.1128/mBio.00282-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosutti A., Scaggiante B., Grassi G., Guarnieri G., Biolo G. (2007). Overexpression of the elongation factor 1A1 relates to muscle proteolysis and proapoptotic p66(ShcA) gene transcription in hypercatabolic trauma patients. Metabolism 56 1629–1634. 10.1016/j.metabol.2007.07.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boysen A., Borch J., Krogh T. J., Hjerno K., Moller-Jensen J. (2015). SILAC-based comparative analysis of pathogenic Escherichia coli secretomes. J. Microbiol. Methods 116 66–79. 10.1016/j.mimet.2015.06.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bulmer D. M., Kharraz L., Grant A. J., Dean P., Morgan F. J. E., Karavolos M. H., et al. (2012). The bacterial cytoskeleton modulates motility, type 3 secretion, and colonization in Salmonella. PLoS Pathog. 8:e1002500. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002500 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burtnick M. N., Brett P. J., DeShazer D. (2014). Proteomic analysis of the Burkholderia pseudomallei type II secretome reveals hydrolytic enzymes, novel proteins, and the deubiquitinase TssM. Infect. Immun. 82 3214–3226. 10.1128/IAI.01739-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butland G., Peregrin-Alvarez J. M., Li J., Yang W., Yang X., Canadien V., et al. (2005). Interaction network containing conserved and essential protein complexes in Escherichia coli. Nature 433 531–537. 10.1038/nature03239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caamano-Antelo S., Fernandez-No I. C., Bohme K., Ezzat-Alnakip M., Quintela-Baluja M., Barros-Velazquez J., et al. (2015). Genetic discrimination of foodborne pathogenic and spoilage Bacillus spp. based on three housekeeping genes. Food Microbiol. 46 288–298. 10.1016/j.fm.2014.08.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cacan E., Kratzer J. T., Cole M. F., Gaucher E. A. (2013). Interchanging functionality among homologous elongation factors using signatures of heterotachy. J. Mol. Evol. 76 4–12. 10.1007/s00239-013-9540-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Candela M., Centanni M., Fiori J., Biagi E., Turroni S., Orrico C., et al. (2010). DnaK from Bifidobacterium animalis subsp. Lactis is a surface-exposed human plasminogen receptor upregulated in response to bile salts. Microbiology 156 1609–1618. 10.1099/mic.0.038307-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao Y., Bazemore-Walker C. R. (2014). Proteomic profiling of the surface-exposed cell envelope proteins of Caulobacter crescentus. J. Proteomics 97 187–194. 10.1016/j.jprot.2013.08.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter L. L., Bayat L., Moreno F., Kling M. A., Price L. H., Tyrka A. R., et al. (2008). Decreased cerebrospinal fluid concentrations of substance P in treatment-resistant depression and lack of alteration after acute adjunct vagus nerve stimulation therapy. Psychiatry Res. 157 123–129. 10.1016/j.psychres.2007.04.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrasco S. E., Yang Y., Troxell B., Yang X., Pal U., Yang X. F. (2015). Borrelia burgdorferi elongation factor EF-Tu is an immunogenic protein during Lyme borreliosis. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 4:e54. 10.1038/emi.2015.54 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chande A. G., Siddiqui Z., Midha M. K., Sirohi V., Ravichandran S., Rao K. V. (2015). Selective enrichment of mycobacterial proteins from infected host macrophages. Sci. Rep. 5:13430. 10.1038/srep13430 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiu K. H., Wang L. H., Tsai T. T., Lei H. Y., Liao P. C. (2016). Secretomic analysis of host-pathogen interactions reveals that elongation Factor-Tu is a potential adherence factor of Helicobacter pylori during pathogenesis. J. Proteome Res. 16 264–273. 10.1021/acs.jproteome.6b00584 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi D. S., Kim D. K., Choi S. J., Lee J., Choi J. P., Rho S., et al. (2011). Proteomic analysis of outer membrane vesicles derived from Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Proteomics 11 3424–3429. 10.1002/pmic.201000212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christie-Oleza J. A., Armengaud J., Guerin P., Scanlan D. J. (2015a). Functional distinctness in the exoproteomes of marine Synechococcus. Env. Microbiol. 17 3781–3794. 10.1111/1462-2920.12822 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christie-Oleza J. A., Scanlan D. J., Armengaud J. (2015b). “You produce while I clean up”, a strategy revealed by exoproteomics during Synechococcus-Roseobacter interactions. Proteomics 15 3454–3462. 10.1002/pmic.201400562 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung M.-C., Tonry J. H., Narayanan A., Manes N. P., Mackie R. S., Gutting B., et al. (2011). Bacillus anthracis interacts with plasmin(ogen) to evade C3b-dependent innate immunity. PLoS One 6:e18119. 10.1371/journal.pone.0018119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Churchward C. P., Rosales R. S., Gielbert A., Dominguez M., Nicholas R. A., Ayling R. D. (2015). Immunoproteomic characterisation of Mycoplasma mycoides subspecies capri by mass spectrometry analysis of two-dimensional electrophoresis spots and western blot. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 67 364–371. 10.1111/jphp.12344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cianfanelli F. R., Monlezun L., Coulthurst S. J. (2016). Aim, load, fire: the type VI secretion system, a bacterial nanoweapon. Trends Microbiol. 24 51–62. 10.1016/j.tim.2015.10.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clair G., Lorphelin A., Armengaud J., Duport C. (2013). OhrRA functions as a redox-responsive system controlling toxinogenesis in Bacillus cereus. J. Proteomics 94 527–539. 10.1016/j.jprot.2013.10.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coelho C., Brown L., Maryam M., Vij R., Smith D. F. Q., Burnet M. C., et al. (2019). Listeria monocytogenes virulence factors, including listeriolysin O, are secreted in biologically active extracellular vesicles. J. Biol. Chem. 294 1202–1217. 10.1074/jbc.RA118.006472 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coulthurst S. J. (2013). The type VI secretion system - a widespread and versatile cell targeting system. Res. Microbiol. 164 640–654. 10.1016/j.resmic.2013.03.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowles K. N., Gitai Z. (2010). Surface association and the MreB cytoskeleton regulate pilus production, localization and function in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Mol. Microbiol. 76 1411–1426. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2010.07132.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalla Vecchia E., Shao P. P., Suvorova E., Chiappe D., Hamelin R., Bernier-Latmani R. (2014). Characterization of the surfaceome of the metal-reducing bacterium Desulfotomaculum reducens. Front. Microbiol. 5:432. 10.3389/fmicb.2014.00432 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dallo S. F., Kannan T. R., Blaylock M. W., Baseman J. B. (2002). Elongation factor Tu and E1 beta subunit of pyruvate dehydrogenase complex act as fibronectin binding proteins in Mycoplasma pneumoniae. Mol. Microbiol. 46 1041–1051. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.03207.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dallo S. F., Zhang B., Denno J., Hong S., Tsai A., Haskins W., et al. (2012). Association of Acinetobacter baumannii EF-Tu with cell surface, outer membrane vesicles, and fibronectin. ScientificWorldJournal 2012:128705. 10.1100/2012/128705 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Datar P., Srivastava S., Coutinho E., Govil G. (2004). Substance P: structure, function, and therapeutics. Curr. Top. Med. Chem 4 75–103. 10.2174/1568026043451636 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Defeu Soufo H. J., Reimold C., Breddermann H., Mannherz H. G., Graumann P. L. (2015). Translation elongation factor EF-Tu modulates filament formation of actin-like MreB protein in vitro. J. Mol. Biol. 427 1715–1727. 10.1016/j.jmb.2015.01.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Defeu Soufo H. J., Reimold C., Linne U., Knust T., Gescher J., Graumann P. L. (2010). Bacterial translation elongation factor EF-Tu interacts and colocalizes with actin-like MreB protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107 3163–3168. 10.1073/pnas.0911979107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deutscher A. T., Jenkins C., Minion F. C., Seymour L. M., Padula M. P., Dixon N. E., et al. (2010). Repeat regions R1 and R2 in the P97 paralogue Mhp271 of Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae bind heparin, fibronectin and porcine cilia. Mol. Microbiol. 78 444–458. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2010.07345.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhanani A. S., Bagchi T. (2013). The expression of adhesin EF-Tu in response to mucin and its role in Lactobacillus adhesion and competitive inhibition of enteropathogens to mucin. J. Appl. Microbiol. 115 546–554. 10.1111/jam.12249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhanani A. S., Gaudana S. B., Bagchi T. (2011). The ability of Lactobacillus adhesin EF-Tu to interfere with pathogen adhesion. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 232 777–785. 10.1007/s00217-011-1443-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Doble A. C., Bulmer D. M., Kharraz L., Karavolos M. H., Khan C. M. A. (2012). The function of the bacterial cytoskeleton in Salmonella pathogenesis. Virulence 3 446–449. 10.4161/viru.20993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dominguez D. C., Lopes R., Palomino J. (2009). B. subtilis elongation factor Tu binds Calcium ions. FASEB J. 23:LB211. [Google Scholar]

- Douglas S. D., Ho W. Z., Gettes D. R., Cnaan A., Zhao H., Leserman J., et al. (2001). Elevated substance P levels in HIV-infected men. AIDS 15 2043–2045. 10.1097/00002030-200110190-00019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebner K., Singewald N. (2006). The role of substance P in stress and anxiety responses. Amino Acids 31 251–272. 10.1007/s00726-006-0335-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebner P., Götz F. (2019). Bacterial excretion of cytoplasmic proteins (ECP): occurrence, mechanism, and function. Trends Microbiol. 27 176–187. 10.1016/j.tim.2018.10.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egea L., Aguilera L., Gimenez R., Sorolla M. A., Aguilar J., Badia J., et al. (2007). Role of secreted glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase in the infection mechanism of enterohemorrhagic and enteropathogenic Escherichia coli: interaction of the extracellular enzyme with human plasminogen and fibrinogen. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 39 1190–1203. 10.1016/j.biocel.2007.03.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ejiri S. (2002). Moonlighting functions of polypeptide elongation factor 1: from actin bundling to zinc finger protein R1-associated nuclear localization. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 66 1–21. 10.1271/bbb.66.1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eshghi A., Henderson J., Trent M. S., Picardeau M. (2015). Leptospira interrogans lpxD homologue is required for thermal acclimatization and virulence. Infect. Immun. 83 4314–4321. 10.1128/IAI.00897-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espino E., Koskenniemi K., Mato-Rodriguez L., Nyman T. A., Reunanen J., Koponen J., et al. (2015). Uncovering surface-exposed antigens of Lactobacillus rhamnosus by cell shaving proteomics and two-dimensional immunoblotting. J. Proteome Res. 14 1010–1024. 10.1021/pr501041a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esteban F., Munoz M., Gonzalez-Moles M. A., Rosso M. (2006). A role for substance P in cancer promotion and progression: a mechanism to counteract intracellular death signals following oncogene activation or DNA damage. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 25 137–145. 10.1007/s10555-006-8161-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fehder W. P., Sachs J., Uvaydova M., Douglas S. D. (1997). Substance P as an immune modulator of anxiety. Neuroimmunomodulation 4 42–48. 10.1159/000097314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng L., Niu X., Mei W., Li W., Liu Y., Willias S. P., et al. (2018). Immunogenicity and protective capacity of EF-Tu and FtsZ of Streptococcus suis serotype 2 against lethal infection. Vaccine 36 2581–2588. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2018.03.079 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira R. M., Moreira L. M., Ferro J. A., Soares M. R., Laia M. L., Varani A. M., et al. (2016). Unravelling potential virulence factor candidates in Xanthomonas citri. subsp. citri by secretome analysis. PeerJ 4:e1734. 10.7717/peerj.1734 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filer D., Furano A. V. (1980). Portions of the gene encoding elongation factor Tu are highly conserved in prokaryotes. J. Biol. Chem. 255 728–734. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filer D., Furano A. V. (1981). Duplication of the tuf gene, which encodes peptide chain elongation factor Tu, is widespread in Gram-negative bacteria. J. Bacteriol. 148 1006–1011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furano A. V. (1975). Content of elongation factor Tu in Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 72 4780–4784. 10.1073/pnas.72.12.4780 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furukawa T., Inagaki H., Takai R., Hirai H., Che F. S. (2014). Two distinct EF-Tu epitopes induce immune responses in rice and Arabidopsis. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 27 113–124. 10.1094/MPMI-10-13-0304-R [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaurivaud P., Ganter S., Villard A., Manso-Silvan L., Chevret D., Boulé C., et al. (2018). Mycoplasmas are no exception to extracellular vesicles release: revisiting old concepts. PLoS One 13:e0208160. 10.1371/journal.pone.0208160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Georgiou T., Yu Y. N., Ekunwe S., Buttner M. J., Zuurmond A., Kraal B., et al. (1998). Specific peptide-activated proteolytic cleavage of Escherichia coli elongation factor Tu. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95 2891–2895. 10.1073/pnas.95.6.2891 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gill S., Wight T. N., Frevert C. W. (2010). Proteoglycans: key regulators of pulmonary inflammation and the innate immune response to lung infection. Anat. Rec. Hoboken N. J. 2007 968–981. 10.1002/ar.21094 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goode T., O’Connor T., Hopkins A., Moriarty D., O’Sullivan G. C., Collins J. K., et al. (2003). Neurokinin-1 receptor (NK-1R) expression is induced in human colonic epithelial cells by proinflammatory cytokines and mediates proliferation in response to substance P. J. Cell. Physiol. 197 30–41. 10.1002/jcp.10234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Götz F., Yu W., Dube L., Prax M., Ebner P. (2015). Excretion of cytosolic proteins (ECP) in bacteria. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 305 230–237. 10.1016/j.ijmm.2014.12.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granato D., Bergonzelli G. E., Pridmore R. D., Marvin L., Rouvet M., Corthesy-Theulaz I. E. (2004). Cell surface-associated elongation factor Tu mediates the attachment of Lactobacillus johnsonii NCC533 (La1) to human intestinal cells and mucins. Infect. Immun. 72 2160–2169. 10.1128/iai.72.4.2160-2169.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green E., Mecsas J. (2016). Bacterial secretion systems: an overview, in: Virulence Mechanisms of Bacterial Pathogens. Washington, DC: ASM Press, 215–240. [Google Scholar]

- Green J. V., Orsborn K. I., Zhang M., Tan Q. K. G., Greis K. D., Porollo A., et al. (2013). Heparin-binding motifs and biofilm formation by Candida albicans. J. Infect. Dis. 208 1695–1704. 10.1093/infdis/jit391 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grundel A., Friedrich K., Pfeiffer M., Jacobs E., Dumke R. (2015). Subunits of the pyruvate dehydrogenase cluster of Mycoplasma pneumoniae are surface-displayed proteins that bind and activate human plasminogen. PLoS One 10:e0126600. 10.1371/journal.pone.0126600 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He Y., Wang H., Chen L. (2015). Comparative secretomics reveals novel virulence-associated factors of Vibrio parahaemolyticus. Front. Microbiol. 6:707. 10.3389/fmicb.2015.00707 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson B., Martin A. (2011). Bacterial virulence in the moonlight: multitasking bacterial moonlighting proteins are virulence determinants in infectious disease. Infect. Immun. 79 3476–3491. 10.1128/IAI.00179-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson B., Martin A. (2013). Bacterial moonlighting proteins and bacterial virulence. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 358 155–213. 10.1007/82_2011_188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson B., Nair S., Pallas J., Williams M. A. (2011). Fibronectin: a multidomain host adhesin targeted by bacterial fibronectin-binding proteins. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 35 147–200. 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2010.00243.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heras B., Shouldice S. R., Totsika M., Scanlon M. J., Schembri M. A., Martin J. L. (2009). DSB proteins and bacterial pathogenicity. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 7 215–225. 10.1038/nrmicro2087 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herpfer I., Lieb K. (2005). Substance P receptor antagonists in psychiatry: rationale for development and therapeutic potential. CNS Drugs 19 275–293. 10.2165/00023210-200519040-00001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huberts D. H. E. W., van der Klei I. J. (2010). Moonlighting proteins: An intriguing mode of multitasking. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1803 520–525. 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2010.01.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes D. (1990). Both genes for EF-Tu in Salmonella typhimurium are individually dispensable for growth. J. Mol. Biol. 215 41–51. 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80093-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Igarashi D., Bethke G., Xu Y., Tsuda K., Glazebrook J., Katagiri F. (2013). Pattern-triggered immunity suppresses programmed cell death triggered by fumonisin b1. PLoS One 8:e60769. 10.1371/journal.pone.0060769 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwabe N., Kuma K., Hasegawa M., Osawa S., Miyata T. (1989). Evolutionary relationship of archaebacteria, eubacteria, and eukaryotes inferred from phylogenetic trees of duplicated genes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 86 9355–9359. 10.1073/pnas.86.23.9355 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jain S., Kumar S., Dohre S., Afley P., Sengupta N., Alam S. I. (2014). Identification of a protective protein from stationary-phase exoproteome of Brucella abortus. Pathog. Dis. 70 75–83. 10.1111/2049-632X.12079 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarocki V. M., Santos J., Tacchi J. L., Raymond B. B. A., Deutscher A. T., Jenkins C., et al. (2015). MHJ_0461 is a multifunctional leucine aminopeptidase on the surface of Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae. Open Biol. 5:140175. 10.1098/rsob.140175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jayaraman G., Wu C. W., Liu Y. J., Chien K. Y., Fang J. C., Lyu P. C. (2000). Binding of a de novo designed peptide to specific glycosaminoglycans. FEBS Lett. 482 154–158. 10.1016/s0014-5793(00)01964-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeffery C. J. (1999). Moonlighting proteins. Trends Biochem. Sci. 24 8–11. 10.1016/S0968-0004(98)01335-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeffery C. J. (2005). Mass spectrometry and the search for moonlighting proteins. Mass Spectrom. Rev. 24 772–782. 10.1002/mas.20041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeffery C. J. (2018). Protein moonlighting: what is it, and why is it important? Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B. Biol. Sci. 373:20160523. 10.1098/rstb.2016.0523 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang F., He J., Navarro-Alvarez N., Xu J., Li X., Li P., et al. (2016). Elongation factor Tu and heat shock protein 70 are membrane-associated proteins from Mycoplasma ovipneumoniae capable of inducing strong immune response in mice. PLoS One 11:e0161170. 10.1371/journal.pone.0161170 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jimenez-Munguia I., van Wamel W. J., Olaya-Abril A., Garcia-Cabrera E., Rodriguez-Ortega M. J., Obando I. (2015). Proteomics-driven design of a multiplex bead-based platform to assess natural IgG antibodies to pneumococcal protein antigens in children. J. Proteomics 126 228–233. 10.1016/j.jprot.2015.06.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones L. J., Carballido-Lopez R., Errington J. (2001). Control of cell shape in bacteria: helical, actin-like filaments in Bacillus subtilis. Cell 104 913–922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kainulainen V., Korhonen T. K. (2014). Dancing to another tune-adhesive moonlighting proteins in bacteria. Biol. Basel 3 178–204. 10.3390/biology3010178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaneider N. C., Djanani A., Wiedermann C. J. (2007). Heparan sulfate proteoglycan-involving immunomodulation by cathelicidin antimicrobial peptides LL-37 and PR-39. ScientificWorldJournal 7 1832–1838. 10.1100/tsw.2007.285 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ke D., Boissinot M., Huletsky A., Picard F. J., Frenette J., Ouellette M., et al. (2000). Evidence for horizontal gene transfer in evolution of elongation factor Tu in enterococci. J. Bacteriol. 182 6913–6920. 10.1128/jb.182.24.6913-6920.2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kesimer M., Kilic N., Mehrotra R., Thornton D. J., Sheehan J. K. (2009). Identification of salivary mucin MUC7 binding proteins from Streptococcus gordonii. BMC Microbiol. 9:163. 10.1186/1471-2180-9-163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S. K., Park M. K., Kim S. H., Oh K. G., Jung K. H., Hong C. H., et al. (2014). Identification of stringent response-related and potential serological proteins released from Bacillus anthracis overexpressing the RelA/SpoT homolog, Rsh Bant. Curr. Microbiol. 69 436–444. 10.1007/s00284-014-0606-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kjeldgaard M., Nissen P., Thirup S., Nyborg J. (1993). The crystal structure of elongation factor EF-Tu from Thermus aquaticus in the GTP conformation. Structure 1 35–50. 10.1016/0969-2126(93)90007-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kloppot P., Selle M., Kohler C., Stentzel S., Fuchs S., Liebscher V., et al. (2015). Microarray-based identification of human antibodies against Staphylococcus aureus antigens. Proteomics Clin. Appl. 9 1003–1011. 10.1002/prca.201400123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koenigs A., Zipfel P. F., Kraiczy P. (2015). Translation elongation factor Tuf of Acinetobacter baumannii is a plasminogen-binding protein. PLoS One 10:e0134418. 10.1371/journal.pone.0134418 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komeil D., Padilla-Reynaud R., Lerat S., Simao-Beaunoir A. M., Beaulieu C. (2014). Comparative secretome analysis of Streptomyces scabiei during growth in the presence or absence of potato suberin. Proteome Sci. 12:35. 10.1186/1477-5956-12-35 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krachler A. M., Orth K. (2013). Targeting the bacteria-host interface: strategies in anti-adhesion therapy. Virulence 4 284–294. 10.4161/viru.24606 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]