Abstract

Background:

Sepsis remains a critical illness with high mortality. The authors have recently reported that mouse plasma RNA concentrations are markedly increased during sepsis and closely associated with its severity. Toll-like receptor 7, originally identified as the sensor for single-stranded RNA virus, also mediates host extracellular RNA-induced innate immune responses in vitro and in vivo. Here, the authors hypothesize that innate immune signaling via Toll-like receptor 7 contributes to inflammatory response, organ injury, and mortality during polymicrobial sepsis.

Methods:

Sepsis was created by 1) cecal ligation and puncture or 2) stool slurry peritoneal injection. Wild-type and Toll-like receptor 7 knockout mice, both in C57BL/6 J background, were used. Following endpoints were measured: mortality, acute kidney injury biomarkers, plasma and peritoneal cytokines, blood bacterial loading, peritoneal leukocyte counts, and neutrophil phagocytic function.

Results:

The 11-day overall mortality was 81% in wild-type mice and 48% in Toll-like receptor 7 knockout mice after cecal ligation and puncture (N=27 per group, P=0.0031). Compared with wild-type septic mice, Toll-like receptor 7 knockout septic mice also had lower sepsis severity, attenuated plasma cytokine storm (Wild-type vs. Toll-like receptor 7 knockout, interleukin-6: 43.2 [24.5, 162.7] vs. 4.4 [3.1, 12.0] ng/ml, P=0.003) and peritoneal inflammation, alleviated acute kidney injury (Wild-type vs. Toll-like receptor 7 knockout, neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin: 307 ± 184 vs.139 ± 41 -fold, P=0.0364; kidney injury molecule-1: 40 [16, 49] vs.13[4, 223] -fold, P=0.0704), lower bacterial loading and enhanced leukocyte peritoneal recruitment and phagocytic activities at 24 hours. Moreover, stool slurry from wild-type and Toll-like receptor 7 knockout mice resulted in similar level of sepsis severity, peritoneal cytokines and leukocyte recruitment in wild-type animals after peritoneal injection.

Conclusions:

Toll-like receptor 7 plays an important role in the pathogenesis of polymicrobial sepsis by mediating host innate immune responses and contributes to acute kidney injury and mortality.

Keywords: Toll-like receptor, sepsis, acute kidney injury, bacterial clearance, neutrophil migration, inflammation

INTRODUCTION

Sepsis remains one of the intricate diseases with extremely high mortality. Between 2004-2009, sepsis incidence had a 22.3% annual increase in the United States and the hospital mortality of sepsis was 28.3% 1,2. Although significant progress in our understanding of sepsis pathogenesis has been made during the past decades, the specific therapy for sepsis is still lacking and mortality remains unacceptably high. Therefore, further investigation into the complex molecular and cellular mechanisms of sepsis is warranted to identify new target for future therapeutic intervention.

Pathogen-associated molecular patterns and host damage-associated molecular patterns participate in innate immune activation during pathogen invasion and in sepsis. Toll-like receptors (TLRs) are a pivotal part of host innate immune defense and play a critical role in molecular pattern recognition. Among 10 TLRs, TLR7 and TLR8 were originally identified as the sensor for single-stranded RNA (ssRNA) of viral origins 3-5. Although their genes lie in close proximity on X chromosome 6, only TLR7 is functional in mice 7. Besides viral ssRNAs, TLR7 can also recognize nucleic acids released from bacteria. For instance, human primary monocytes and macrophages sense staphylococcus aureus ssRNA via TLR8 and induces interferon-β production 8. Moreover, vaccine composition formulated with a TLR7-dependent adjuvant induces high and broad protection against Staphylococcus aureus 9. These findings suggest that TLR7 signaling may play an important role in host innate immune response during bacterial infection. Our group has previously reported that host tissue RNAs including microRNAs (miRNAs) were released into the blood circulation in a mouse model of polymicrobial sepsis and the plasma RNA concentrations are closely correlated with the severity of sepsis 10. In vitro and in vivo studies show that extracellular RNAs and miRNA mimics can work as host damage-associated molecular patterns to induce a robust proinflammatory response such as cytokine production, immune cell activation, and complement activation 10-12. Most importantly, the proinflammatory role of these extracellular RNAs and miRNAs proves to be dependent of TLR7-myeloid differentiation primary response 88 (MyD88) signaling both in cell cultures and in a peritonitis model in vivo 10-12. However, the role of extracellular RNA and TLR7 signaling in sepsis pathogenesis remains unclear.

In the present study, we tested the hypothesis that TLR7 sensing plays an important role in mediating host innate immune responses, tissue injury, and mortality following bacterial sepsis. Taking a loss-of-function approach, we examined the impact of TLR7 deficiency to the host systemic and local cytokine responses, immune cell migration, leukocyte phagocytosis, bacterial clearance, acute kidney injury, and mortality during sepsis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

Male and age matched wild-type (WT, C57BL/6 J) and TLR7−/− mice ((Tlr7tm1Flv/J) were purchased from the Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME). All mice were 8 to 16-week-old and weighed between 22-30g. Animals were housed in an animal facility of Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) or University of Maryland School of Medicine for at least one week before experiments under specific pathogen free environment. They were fed with autoclaved bacteria-free diet and the housing facilities were temperature-controlled and air-conditioned with 12h/12h light/dark cycles. All animal protocols were approved by the Subcommittee on Research Animal Care of Massachusetts General Hospital (Boston, MA) and Institutional Animal Care & Use Committee of University of Maryland School of Medicine and followed the guideline of the National Institutes of Health (Bethesda, MD). Simple randomization was used to assign animals and the operators of the surgery (WJ and LG) were blinded to the strain information.

Mouse model of polymicrobial sepsis

Cecal ligation and puncture (CLP) model was slightly modified based on what we described previously and was performed in the morning 13. Briefly, after anesthetization (ketamine 100 mg/kg, xylazine 4 mg/kg), mice were subjected to laparotomy. The cecum was ligated 1.2-1.5 cm from the tip and punctured with an 18-gauge needle through-through. A small drop of feces was squeezed out gently. Sham-operated mice went through the same procedure but without CLP. Postoperatively, mice were administered subcutaneously prewarmed saline (0.3 ml/10g). A dose of 3 mg/kg bupivacaine and 0.1 mg/kg buprenorphine was administered to treat post-operative pain. Rectal temperature was recorded at 24 hours after surgery.

Mortality study

After CLP, mice (n=27/group) were observed every 4 hours for the first 48 hours and every 12 hours for up to 11 days. Experimental operators and observers (WJ and LZ) were blinded to the strain information. Because sham surgery resulted in no mortality 14, no sham mice were included in the mortality study to minimize the unnecessary use of animals.

RNA extraction and quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR)

Kidney samples were collected at 24 hours after surgery (N=6-8/group). RNA was extracted from the kidney with TRIzol (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) and cDNA synthesized with reverse transcriptase. Quantitative RT-PCR was performed as described previously 13. The transcripts of glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH), neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin (NGAL), and kidney injury molecule-1 (KIM-1) were quantified using qRT-PCR with GAPDH as the internal control. The PCR primer sequences are listed below: GAPDH (Forward: 5’-AACTTTGGCATTGTGGAAGG-3’, Reverse: 5’-GGATGCAGGGATGATGTTCT-3’); NGAL (Forward: 5’-CTCAGAACTTGATCCCTGCC-3’, Reverse: 5’-TCCTTGAGGCCCAGAGACTT-3’); KIM-1 (Forward: 5’-CATTTAGGCCTCATACTGC-3’, Reverse: 5’-ACAAGCAGAAGATGGGCATT-3’). Transcript expression was calculated using the comparative Ct method normalized to GAPDH (2−ΔΔCt) and expressed as the fold difference in the CLP or treatment group over the WT-sham group.

Bacterial colony formation and quantification

Twenty-four hours after sham or CLP procedures, five ml of sterile normal saline was injected into the peritoneal cavities of WT and TLR7−/− mice (N=8/group). After gently mixed, 4 ml of the peritoneal lavage was harvested. Blood was collected through inferior vena cava in EDTA-containing tubes. Bacterial counts of the peritoneal lavage and blood were determined by incubating 50 μl of the samples with serial dilutions on Trypticase soy agar plate containing 5% sheep blood (BD Company, Sparks, MD) at 37°C for 36 hours. Colonies were counted and expressed as log10 of units per milliliter of lavage fluid or blood. The supernatant of peritoneal lavage was stored at −80 °C for ELISA analysis.

Cytokine ELISA

Twenty-four hours after procedure, plasma and peritoneal lavages were collected and measured for interleukin 6 (IL-6), interleukin 1β (IL-1β), tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) and chemokine ligand 2 (CXCL2) using commercially available DuoSet or Quantikine HS ELISA kits (R&D systems, Minneapolis, MN) as described in the manufacturer’s instructions.

Flow cytometry analysis of peritoneal cell population and phagocytic function

Yellow-green fluorescent carboxylate-modified microspheres (Invitrogen/Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA) were opsonized by incubating with Roswell Park Memorial Institute-1640 cell culture medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) at 37 °C for 30 mins. The opsonized microspheres were then injected intraperitoneally at 23 hours after sham or CLP surgery in a dose of 108 microspheres/200 μl volume per mouse. After one hour, 5 ml of sterile normal saline was injected and mixed thoroughly by gentle massage. Four milliliters of peritoneal lavage fluid were collected and centrifuged. A faction of cells (4 × 105) were stained with the following surface markers: CD45-Phycoerythrin (clone 30-F11, 1:1500 dilution, BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, ), Ly6G-Brillian Violet 421 (clone 1A8, 1:100 dilution, BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA), F4/80-Alexa Fluro 647 (clone T45-2342, 1:100 dilution, BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) at 4 °C for 30 min in the dark as described previously 12. Cells were washed twice in 4 ml of ice cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) buffer and resuspended in PBS containing 5% FBS, and then flow cytometry analysis was performed using a BD LSR II flow cytometer. The phagocytic function in single cell was expressed as the mean fluorescence intensity of microsphere within the chosen cell population.

Leukocytes count in the blood

Twenty-four hours after sham or CLP surgery, mice (N=9-12/group) were anesthetized as described above. Blood was collected via cardiac puncture and transferred to blood collection tubes containing 3.2% sodium citrate as anti-coagulant (Grenier, FisherScientific, Pittsburgh, PA). Leukocyte count was tested using an automated cell counter (Beckman COULTER® AC-T diff™ Analyzer, Brea, CA).

Cecal Slurry (CS) model of polymicrobial sepsis

Male and age matched WT and TLR7−/− mice were euthanized by anesthesia (ketamine 100 mg/kg, xylazine 4 mg/kg) followed by cervical dislocation. The whole cecum was dissected and the cecal contents were then collected using sterile forceps and spatula, weighed and suspended in 5% dextrose (Hospira, Lake Forest, IL) in water to make a cecal contents slurry at a concentration of 80 mg/ml. This CS was mixed well by vortex and filtered through a 100 μm sterile cell strainer. Mice were received the CS intraperitoneally in a dose of 1.3 mg/g body weight in 500 μl volume. The vehicle group receive the same volume of 5% dextrose in water only. Twenty hours later, peritoneal lavage and plasma were collected. The cell migration and cytokine production were measured as mentioned above. The operator was blinded to the strain information.

Statistical Analysis

Mice were randomly allocated to treatment groups in balanced distribution. No statistical power calculation was conducted before the current study. Sample sizes were estimated based on previous similar studies and our preliminary data. Specific comparisons were made based on scientific hypotheses for the study. Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 6 software (GraphPad Software Inc., La Jolla, CA). Normality of all numerical data was assessed using D’Agostino-Pearson test. A parametric test was used if the hypothesis of normality was not rejected. Because of data variance observed in the study, unequal variance unpaired t-test was assumed in all parametric comparisons with interval variables. Nonparametric Mann-Whitney U-tests were applied to the data that did not pass normality test. Data are presented as mean ± SD when a parametric test was used or as median (interquartile range) otherwise. The survival distributions were presented as ratio variables and compared using log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test. There were no lost data. All data were included. The null hypothesis was rejected for P<0.05 with two-tails.

RESULTS

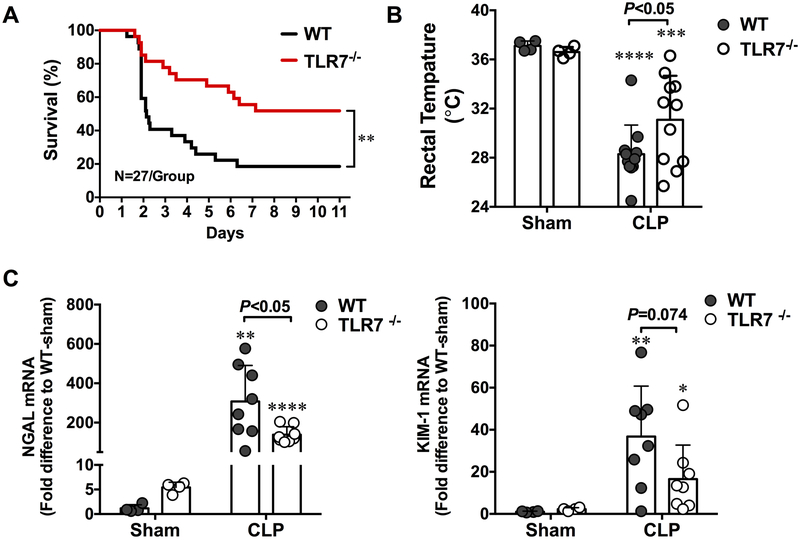

TLR7−/− mice have reduced mortality and attenuated acute kidney injury in polymicrobial sepsis

As shown in Fig. 1A, WT CLP mice showed an accumulated mortality of 48% on day 2 and 81% on day 11. In comparison, TLR7−/− CLP mice had a marked reduction in mortality (18% on day 2 and 48% on day 11, N=27, P=0.0031). Body temperature reportedly is a reliable surrogate marker of sepsis severity in mouse models 15. Consistent with the mortality data, WT CLP mice displayed a significantly lower rectal temperature compared with TLR7−/− CLP mice (28.3 ± 0.7 vs. 31.1±1.1 °C, P=0.0448) (Fig.1B) at 24 hours after surgery, suggesting a less severe septic condition in these TLR7−/− mice. NGAL 16-18 and KIM-1 19 are two highly sensitive biomarkers of acute kidney injury (AKI). As illustrated in Fig. 1C, WT CLP mice quickly developed AKI as evidenced by markedly elevated kidney NGAL and KIM-1 gene expression. TLR7−/− CLP mice had substantially lower NGAL (139 ± 41 vs. 307 ± 184 folds, P=0.0364) and KIM-1 (13[4, 223] vs. 40 [16, 49] folds, P=0.0704) gene expression as compared with WT-CLP. Together, these data suggest that lack of TLR7 signaling confers both survival and kidney-protecting benefits in the mouse model of polymicrobial sepsis.

Figure 1. Toll-like receptor 7-deficient mice have improved survival and attenuated acute kidney injury after polymicrobial sepsis.

(A) Survival rate of WT and TLR7−/− mice during sepsis. Mice were subjected to CLP surgery and observed for survival for up to 11 days. **P<0.01, n=27 in WT and TLR7 −/− group. (B) Rectal temperature at 24 hours after CLP surgery. ***P<0.001, **** P<0.0001vs. sham group. Unequal variance t-test, N=11/group. (C) Kidney NGAL and KIM-1 mRNA expression in WT and TLR7−/− mice at 24 hours post-procedure. * P<0.05, **P<0.01, ****P<0.001 vs. sham group. Unequal variance t-test. N=4-8/group. Each bar represents mean±SD. NGAL = neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin, KIM-1 = kidney injury molecule-, CLP = cecal ligation and puncture, WT = wild-type.

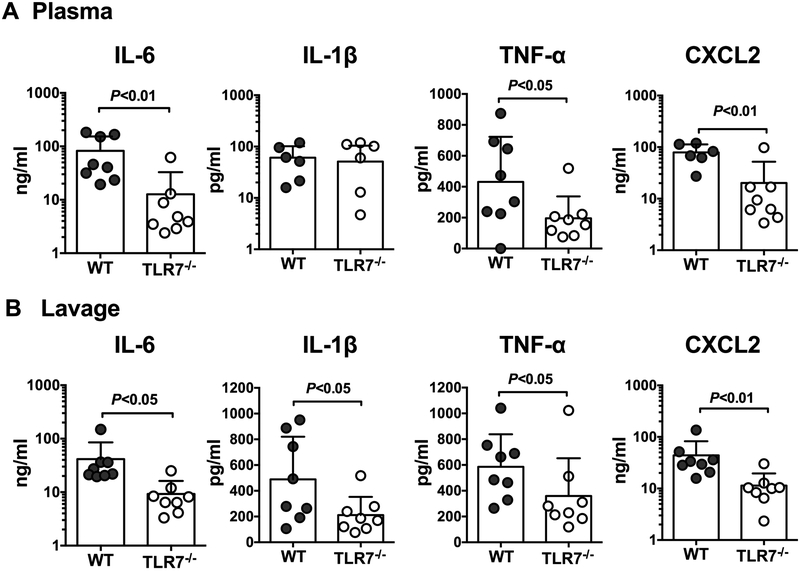

Lack of TLR7 leads to reduced cytokine production and bacterial loading in sepsis

Early mortality and organ injury in sepsis is likely attributed to cytokine storm and other innate immune activities during the initial host response to invading pathogens 20. To determine the role of TLR7 signaling in host inflammation after polymicrobial sepsis, we measured the proinflammatory cytokines, IL-6, IL-1β, and TNF-α, and the chemokine CXCL2, known for their key role in sepsis pathogenesis. As illustrated in Fig. 2, we observed significant reduction in IL-6 and TNF-α, and CXCL2, in the plasma and the peritoneal lavages of TLR7−/− mice as compared to that of WT mice after CLP. However, IL-1β was only reduced in the peritoneal lavages, but not in the plasma, of TLR7−/− CLP mice when compared with WT CLP mice. To determine the role of TLR7 in bacterial clearance, we measured the bacterial loading both in the blood and the peritoneal lavage 24 hours after sham and CLP surgery. Almost no bacterial colonies were identified from sham samples. As shown in Fig. 3, there were marked bacterial loads in both blood and peritoneal lavage of CLP mice. Compared to WT CLP mice, TLR7−/− CLP mice had a marked reduction in bacterial loading in both blood and the peritoneal lavage.

Figure 2. TLR7−/− mice display lower proinflammatory cytokine production in both blood circulation and peritoneal cavity following CLP procedure.

Twenty-four hours after CLP procedure, cytokines in the plasma and peritoneal lavage were measured by ELISA. (A) Plasma IL-6, IL-1 β, TNF-α, CXCL2 concentration. IL-6 and TNF-α are expressed as median with interquartile range and analyzed by Mann-Whitney U test. IL-1β and CXCL2 are expressed as mean ± SD and analyzed by unequal variance t-test; (B) Peritoneal lavage IL-6, IL-1 β, TNF-α, CXCL2. N=6-8/group. IL-6, IL-1 β and TNF-α are expressed as median with interquartile range and analyzed by Mann-Whitney U test. CXCL2 is expressed as mean ± SD and analyzed by unequal variance t-test. WT = wild-type, CLP = cecal ligation and puncture.

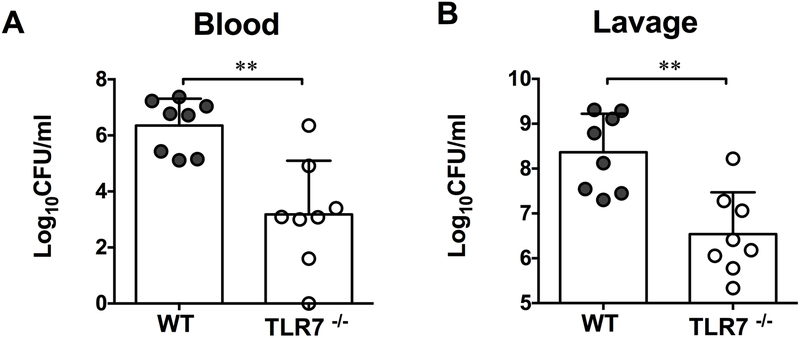

Figure 3. Bacterial loading in the blood and peritoneal cavity.

Both the blood and peritoneal lavage were harvested 24 hours after sham or CLP procedure. After serial dilutions, anticoagulated blood and lavage were incubated on agar plates and bacterial colony-forming units (CFU) /ml were calculated and plotted in a Log10 scale. (A) Bacterial loading in the blood. (B) Bacterial loading in the peritoneal space. **P<0.01. Unequal variance t-test. N=8 mice/group. Data are expressed as mean ± SD. CLP = cecal ligation and puncture.

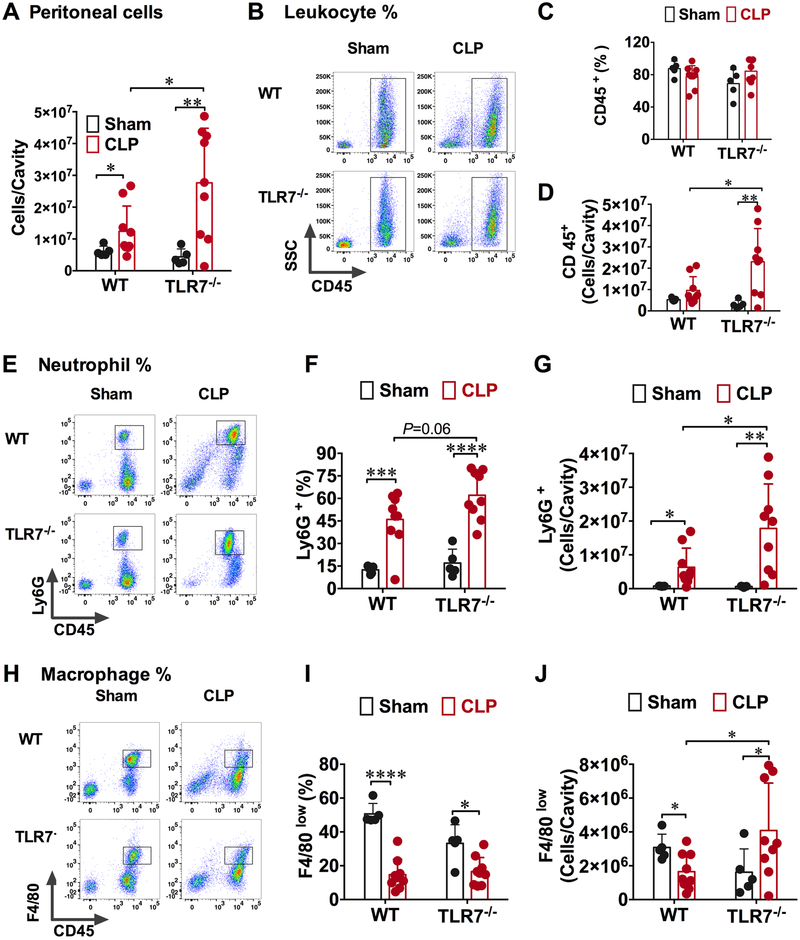

TLR7−/− mice exhibited enhanced neutrophil and small peritoneal macrophage recruitment after CLP

The reduced bacterial loading in TLR7−/− mice as compared to WT mice suggested a possible role of TLR7 activation in functional impairment of immune effector cells during sepsis. TLR7 activation is known for its role in human CD4(+) T cell anergy 21. Thus, we investigated how polymicrobial infection after CLP affected peritoneal residential cells as well as leukocytes recruited into the peritoneal cavity in both WT and TLR7−/− mice. As shown in Fig. 4A, there was a significant increase in the peritoneal cells in WT and TLR7−/− septic mice as compared with their sham counterparts. Comparing the two CLP groups, TLR7−/− mice had higher peritoneal cells than WT ([28.0 ± 17.2] × 106 vs. [12.4 ± 7.9] × 106 cells/cavity, P=0.0339). To identify the peritoneal cell populations, we stained the cells with fluorescence-labeled antibodies for specific leukocyte surface markers and analyzed them using flow cytometry. Supplement Fig. 1 illustrates the gating strategy used to identify the various leukocyte populations. Leukocytes were identified as CD45+ population, neutrophils as CD45+Ly6G+, and small resident macrophage as CD45+F4/80low. With this gating strategy, we found that although the percentage of CD45+ leukocytes was about the same in WT and TLR7−/− mice (Fig. 4B-C), TLR7−/− CLP mice had many more CD45+ leukocytes in the peritoneal cavity than that of WT-CLP mice (Fig. 4D). Moreover, neutrophil is a major phagocyte important for controlling bacterial dissemination during infection. We found that the percentage as well as the total numbers of the peritoneal CD45+Ly6G+ neutrophils increased in both WT CLP and TLR7−/− CLP mice compared with sham mice (Fig. 4 E-G). TLR7−/− CLP mice had even higher CD45+Ly6G+ neutrophil numbers than that of WT CLP mice ([17.8 ±13.2] × 106 vs. [6.3 ± 5.7] × 106, P=0.0357) (Fig. 4G). Another important type of phagocytes in the peritoneal cavity is macrophage. A previous study has identified two distinct peritoneal macrophage subsets, namely large peritoneal macrophages expressing CD11b high F4/80high MHC− and small peritoneal macrophages expressing CD11b+ F4/80low MHC+22. Large peritoneal cells are the major resident macrophage in unoperated naïve mice, whereas the small peritoneal macrophages become the predominate type in lipopolysaccharide-injected mice and are mainly derived from blood monocytes 22. We noted that large peritoneal macrophages with F4/80high expression were greatly diminished within 24 hours in WT mice subjected to sham surgery compared to unoperated naïve mice (data not shown), whereas small peritoneal macrophages with F4/80low expression appeared as the predominate population (Fig. 4H). As indicated in Fig. 4I, both WT and TLR7−/− CLP groups had markedly reduced percentage of CD45+/F4/80low peritoneal macrophages compared with their sham controls. TLR7−/− mice, however, appeared to have significantly higher numbers of CD45+/F4/80low macrophages than WT mice ([1.7 ± 1.1] × 106 vs. [4.1 ± 2.8] × 106 cells/cavity, P=0.0343, Fig. 4J). We also measured leukocytes in the blood. As indicated in Table I, there was a trend that blood leukocyte counts in TLR7−/− mice were slightly higher than that of WT mice ([3.2 ± 1.2] × 103 cells/μl vs. [4.8 ± 2.1] × 103 cells/μl, P=0.054) after sham procedure. In the mice undergoing CLP, the blood leukocyte counts dropped significantly in both WT and TLR7−/− mice.

Figure 4: Absence of TLR7 enhances neutrophil migration to the peritoneal space during polymicrobial sepsis.

Twenty-four hours after surgery, peritoneal cells were harvested and analyzed using flow cytometry. Surface marker: CD45+ for leukocyte (LE), CD45+Ly6G+ for neutrophil (NE) and CD45+ F4/80low for small peritoneal macrophage (MΦ). A) Total number of cells in the peritoneal cavity at 24 hours after sham or CLP procedure. * P<0.05, ** P<0.01 (B) Representative flow cytometry plots of leukocytes (CD45+) population. (C) Percentage of leukocytes (CD45+) in the peritoneal space. (D) Leukocytes increased significantly in the TLR7−/− septic mice as compared to that of WT septic mice. N=5-9, * P<0.05, ** P<0.01. (E) Flow cytometry plots depicting the increase in neutrophil percentage in the peritoneal cavity of TLR7−/− septic mice. (F, G) TLR7-deficiency led to marked neutrophil migration to infection site in both percentage and absolute numbers. N=5-9, * P<0.05, ** P<0.01, *** P<0.001, **** P<0.0001. (H) Representative flow cytometry plots of small resident macrophages in the peritoneal space. (I) Percentage of small resident macrophage decreased following sepsis. N=5-9/group * P<0.05, **** P<0.0001. (J) TLR7 deficiency increased the small macrophage numbers. N=5-9/ group. * P<0.05. Unequal variance t-test. Data are expressed as mean ± SD. WT = wild-type, CLP = cecal ligation and puncture, FSC = forward scatter, SSC = side scatter

Table 1:

Leukocytes in the blood at 24 hours after procedure

P=0.054 vs. TLR7−/−-sham

P=0.0025 vs. WT-sham

P=0.0006 vs. TLR7−/− -sham. N=9-12. CLP = cecal ligation and puncture. Unequal variance t-test. Data are expressed as mean ± SD.

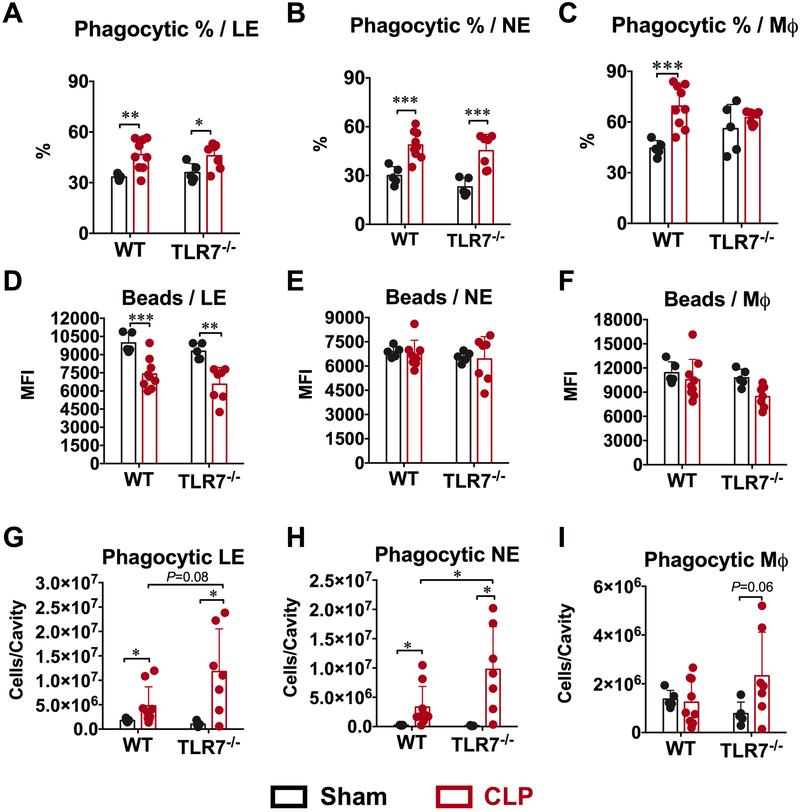

Phagocytic function of the peritoneal neutrophils and macrophages

Next, we tested whether TLR7 signaling plays a role in regulating phagocytic function of the peritoneal leukocytes. We used an in vivo phagocytosis assay in which opsonized yellow-green fluorescence-labeled microsphere beads were injected intraperitoneally at 23 hours after sham or CLP procedure and 1 hour later, the peritoneal cells were harvested and immediately chilled followed by surface marker staining. As shown in Supplement Fig. 2, the percentage of cells that contained phagocytosed beads was calculated as the percentage of fluorescein-positive cells in leukocytes (CD45+), neutrophils (CD45+Ly6G+) or macrophages (CD45+ F4/80low). As shown in Fig. 5A-B, compared to sham mice, the percentage of leukocytes and neutrophils with phagocytosed fluorescent beads increased significantly and equally in both WT and TLR7−/− CLP mice. The percentage of phagocytic macrophages increased significantly in WT CLP mice compared to sham but maintained the same in TLR7−/− mice (Fig. 5C). Next, we measured the capacity of single cell to phagocytose beads, which was expressed as mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of microspheres within each cell population. As shown in Fig. 5D, the MFI of leukocytes leukocyte (CD45+) dropped significantly in WT CLP mice compared to sham. TLR7−/− mice showed the same bead phagocytosis capacity in single cell and displayed the same degree of decrease as the WT CLP mice. For neutrophils and macrophages, the single cell phagocytosis capacity remains the same in WT and TLR7−/− mice between sham and CLP group (Fig. 5E-F). Finally, we calculated the total number of leukocytes, neutrophils, and macrophages that had phagocytosed beads in the peritoneal cavity to assess the overall phagocytic capacity of the individual cell population. As illustrated in Fig. 5G-I, compared to WT CLP mice, TLR7−/− CLP mice had a marked increase in the number of the phagocytic leukocytes and neutrophils, and significant more phagocytic macrophages compared with the sham mice.

Figure 5: TLR7 deficiency increased the phagocytic cells following sepsis.

108 fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-labeled carboxylate-modified microspheres (beads) in 200 μl were injected intraperitoneally at 23 hours following sham or CLP surgery. One hour later, peritoneal cells were collected and analyzed using flow cytometry. (A, B, C) Percentage of cells with phagocytic function. (D, E, F) Single cell phagocytic function. (G, H, I) TLR7 deficiency increased phagocytic cells in septic mice. * P<0.05, ** P<0.01, *** P<0.001. N=5-9 mice/ group. Unequal variance t-test. Data are expressed as mean±SD. WT = wild-type, CLP = cecal ligation and puncture, LE = leukocytes, NE = neutrophil, MΦ = macrophage, MFI=mean fluorescence intensity.

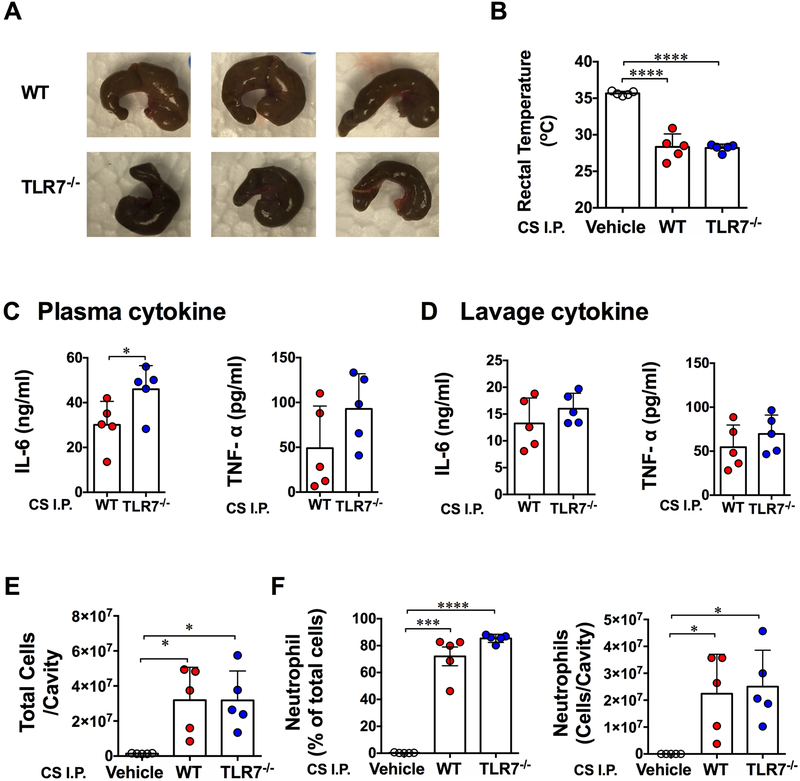

Effect of WT and TLR7−/− cecal slurry in WT mice after peritoneal injection

The gut microbiota is shaped by both environment and host genetics 23. To examine the possibility that the difference in colonic microbiome between WT and TLR7−/− mice contributes to the beneficial effects seen TLR7−/− mice after CLP, we injected equal amount of cecal slurry (CS) from WT or TLR7−/− mice (Fig. 6A) to the WT recipient mice. Twenty hours later, body temperature, cytokines and leukocyte migration were detected. As shown in Fig. 6B, both WT and TLR7−/− CS injection resulted in similarly severe hypothermia in recipient WT mice (28.3 ± 1.8 vs. 28.2 ± 0.5 °C). Injection of WT and TLR7−/− CS also induced a marked increase in cytokine production. Interestingly, whereas the wild-type mice that received Toll-like receptor 7−/− cecal slurry displayed significantly higher plasma IL-6 production than the ones that received WT cecal slurry (Fig. 6C), no difference was observed in peritoneal IL-6 and TNF-α production between the two groups (Fig. 6D). Moreover, both WT and TLR7−/− CS elicited marked (but to the same degree) peritoneal neutrophil migration compared to the vehicle control and ([3.20 ± 1.80] × 107 vs. [3.20 ± 1.70] × 107 vs. [0.14 ± 0.02] × 107 cells/cavity, WT CS vs. TLR7−/− CS vs. Vehicle, Fig. 6E-F).

Figure 6: Cecal slurry of WT and TLR7−/− mice induces systemic and peritoneal inflammation and leukocyte migration in WT mice after peritoneal injection.

Cecal slurry collected from WT and TLR7−/− mice was intraperitoneally injected to WT recipient mice. Twenty hours later, rectal temperature, cytokine and peritoneal cell migration were measured. (A) Representative pictures of mouse cecum from WT and TLR7−/− mice. (B) Rectal temperature. Data was analyzed by One-Way ANOVA. (C, D) Cytokine production in the plasma and peritoneal cavity. Unequal variance t-test. (E) Total cell numbers in the peritoneal cavity. Unequal variance t-test. (F) Percentage and absolute number of neutrophil migrated to peritoneal space. Unequal variance t-test. Each bar represents mean±SD. * P<0.05, *** P<0.001, **** P<0.0001. N= 5/group. Vehicle=5% dextrose in water, CS=cecal slurry, I.P.=intraperitoneal injection.

DISCUSSION

In the recent Sepsis-3 definition, sepsis is defined as life-threatening organ dysfunction caused by a dysregulated host response to infection 24. The new definition emphasizes the primacy of the non-homeostatic host response to infection. The host response is initiated by pathogen-associated molecular patterns and further amplified by danger-associated molecular patterns during host-pathogen interaction 20. As a result, excessive inflammatory response contributed to organ injury and mortality especially in the early stage of sepsis 20,25. Previous studies from our lab and others’ have demonstrated that extracellular RNAs derived from bacteria and host are recognized by TLR7 and modulate host innate and adaptive immune responses 9-11,21. However, whether or not TLR7 receptor signaling plays a role in sepsis progression and outcomes was unclear. In the current study, we made three major findings. First, TLR7−/− had improved survival and attenuated acute kidney injury following CLP. Second, TLR7−/− mice had a lower systemic and local cytokine responses but maintained a strong ability to clear bacteria. Third, TLR7−/− mice had enhanced peritoneal leukocyte recruitment and phagocytic activity during polymicrobial sepsis.

TLR7 recognizes viral or other single-stranded RNA 3. Specific examples include vesicular stomatitis virus, human immunodeficiency virus-1, hepatitis B and C virus 4,5,26-28 or synthetic guanine-rich RNA sequence analogs such as Resiquimod (R848) and imiquimod (R837) 27,29. In addition to its anti-viral effects, a number of studies have revealed the important role of TLR7 in patho-immunology of many diseases where inflammation plays a pivotal role such as cancer metastasis 30, systemic lupus erythematosus 31, Juvenile dermatomyositis 32, and neurodegeneration 33. For example, study by Fabbri, et al. reported that TLR7 binding to extracellular miRNAs released from tumor triggered a prometastatic inflammatory response, which may lead to tumor growth 30. We have found that cardiac or splenic RNA and synthetic miRNAs rich in uridine induces proinflammatory response including cytokine and complement production in vitro and neutrophil migration in vivo 10-12. The proinflammatory responses are mediated through TLR7-MyD88 signaling induced by TLR7 dimerization in the endosome upon ligand binding 34 and by activation of nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-κB), mitogen-activated protein kinase or type I interferon pathway 10,11,35-37. TLR7 also reportedly mediates cell injury via MyD88-indepenent mechanisms. Park, et al. found that interaction of TLR7 and transient receptor potential ankyrin 1 is required to recognize extracellular miRNAs for activation and excitation of nociceptive sensory neurons in eliciting pain, which does not require MyD88 38. Sterile α and armadillo motif containing protein 1, but not MyD88, was demonstrated to mediate TLR7/TLR9-induced apoptosis in neurons 39. In current study, we found that mice lacking TLR7 displayed a significantly attenuated proinflammatory cytokine including IL-6, TNF-α and IL-1β both in the blood and in local infection sites during sepsis. Similar findings were also reported with other innate immune receptors, where genetic deficiency of TLR2 or MyD88 confers beneficial effect against polymicrobial sepsis 40,41. On the other hand, Koerner et al. 42 reported that stimulation of TLR7 before the colon ascendens stent peritonitis improved the immune control of the inflammatory response in the mice. Mice treated with R848 (TLR7 ligand) before sepsis induction exhibited a reduction of proinflammatory cytokine in the spleen and alleviated bacterial loading in the peritoneum/spleen as well as decreased thymus and spleen apoptosis, indicating a trend of improvement even though no mortality data was reported. The protective effect may in part attribute to the TLR ligand “tolerance” effect, in which exposure of innate immune cells to TLR ligands induces a state of temporary refractoriness to a subsequent exposure of a TLR ligand.

The rate of acute kidney injury is directly proportional to the severity of sepsis. The combination of acute kidney injury and sepsis is associated with a 70% mortality rate when compared with a 45% mortality rate in patients with acute renal failure alone 43. We found that absence of TLR7 resulted in alleviated sepsis-induced acute kidney injury as evidenced by reduced NGAL and KIM-1 in the kidney. This may be secondary to reduced proinflammatory cytokines in TLR7−/− septic mice as Nechemia-Arbely et.al.44 demonstrated that inflammatory cytokine such as IL-6 promotes peritubular neutrophils accumulation and exacerbates renal injury. Studies also found a significant expansion of myeloid-derived suppressor cells and severe podocyte injury in glomeruli of kidneys in TLR7 agonist imiquimod-induced lupus mice 45, implicating a direct role of TLR7 in kidney injury.

One survival factor in bacterial sepsis is successful control of bacterial dissemination. In the present study, we found that TLR7-deficient mice had improved bacterial clearance both in the peritoneal space and in the blood as compared to WT mice following CLP. To identify the possible mechanisms for the enhanced bacterial clearance in TLR7−/− mice, we tested leukocyte migration to the infection site, which is essential for controlling bacterial burden and eliminating systemic spread of infection 46,47. We found markedly enhanced leukocytes, mainly neutrophils, migration to the peritoneal space in the TLR7−/− after CLP. This may represent one of the potential mechanisms responsible for the improved bacterial clearance and survival in septic TLR7−/− mice. The exact mechanism for the enhanced neutrophil migration to the peritoneal cavity in TLR7−/− mice is still unclear. In general, bacterial products, cytokine/chemokine gradients, and phagocyte chemokine receptor expression can all modulate neutrophil migratory responses during sepsis 48. For example, TLR2 deficiency reportedly enhances neutrophil migratory function in sepsis by promoting neutrophil chemokine receptor CXCR2 while the systemic cytokine levels were lower in TLR2 KO mice 49. In addition, Impaired neutrophil migration is thought to be attributable to internalization of chemokine receptor CXCR2 in circulating neutrophils of mice or patients with severe sepsis 47,50-52 with involvement of TNF-α 53. Neutrophils treated with TNF-α exhibit reduced chemotaxis toward CXCL2 53. Therefore, we speculate that suppressed production of plasma TNF-α in TLR7−/− septic mice may in part contribute to enhanced neutrophil migration.

Different from neutrophils, the percentage of peritoneal macrophages among leukocytes decreased dramatically following sepsis in both WT and TLR7−/− mice compared to that of sham mice. But the absolute number of macrophages was still significantly higher in TLR7-deficient septic mice, suggesting preserved macrophage ability against bacteria. In line with our findings, Talreja, et al. reported TLR7/8-primed macrophages exhibited decreased bacterial clearance when infected with live bacteria 35. Phagocytic function of immune cells is another important host defense against invading bacteria 54. Although TLR7 deficiency did not alter the phagocytic function per se of the peritoneal neutrophils and macrophages, we did observe an increase in the number of phagocytic neutrophils and macrophages positive with fluorescent beads in these mice. Taken together, the enhanced bacterial clearance in TLR7−/− septic mice are likely attributed to enhanced neutrophil and monocyte recruitment into the peritoneal cavity and hence increased phagocytic capability.

There is evidence that changes in host gene have significant effects on mouse microbiome 23. For example, the loss of TLR5 altered the gut microbiota and promoted the development of metabolic syndrome in these mice 55. To determine if the decreased inflammatory response observed in TLR7−/− mice was secondary to less pathogenic virulence of cecal bacteria in these mice, we injected WT mice intraperitoneally with cecal slurry harvested from WT and TLR7−/− mice. Lack of difference in body temperature, peritoneal cytokines and leukocyte migration between the mice receiving WT vs. TLR7−/− cecal slurry strongly suggest that WT and TLR7−/− mouse slurry exhibit similar virulence and proinflammatory effects, and that any potential difference in the bowel microbiomes in WT and TLR7−/− mice may not explain the survival benefit and other effects seen in TLR7−/− septic mice.

In summary, we demonstrated that mice lacking TLR7 exhibited attenuated systemic cytokine production, reduced acute kidney injury and bacterial loading, and improved survival compared with WT mice after polymicrobial infection. These data suggest that signaling via TLR7, a sensor for both pathogen and host single-stranded RNA, may play an important role in sepsis pathogenesis.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding Statement:

This work was supported in part by the NIH (Bethesda, Maryland) grants, R01-GM097259/R01-GM122908 (WC), and R35-GM124775 (LZ), Frontiers in Anesthesia Research Award from International Anesthesia Research Society (San Francisco, California) to WC, and the Shock Faculty Research Award from Shock Society to LZ. WJ was supported by a scholarship from Chinese Scholar Council (No.201406370104).

Footnotes

Prior Presentations: A part of the work presented in this article has been presented at 2016 Anesthesiology Annual Meeting in Chicago, Illinois.

Conflicts of Interest:

The authors declare no competing interests.

REFERENCES

- 1.Levy MM, Artigas A, Phillips GS, Rhodes A, Beale R, Osborn T, Vincent J-L, Townsend S, Lemeshow S, Dellinger RP: Outcomes of the Surviving Sepsis Campaign in intensive care units in the USA and Europe: a prospective cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis 2012; 12: 919–924 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gaieski DF, Edwards JM, Kallan MJ, Carr BG: Benchmarking the incidence and mortality of severe sepsis in the United States. Crit Care Med 2013; 41: 1167–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Heil F, Hemmi H, Hochrein H, Ampenberger F, Kirschning C, Akira S, Lipford G, Wagner H, Bauer S: Species-specific recognition of single-stranded RNA via toll-like receptor 7 and 8. Science 2004; 303: 1526–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Diebold SS, Kaisho T, Hemmi H, Akira S, Reis e Sousa C: Innate antiviral responses by means of TLR7-mediated recognition of single-stranded RNA. Science 2004; 303: 1529–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lund JM, Alexopoulou L, Sato A, Karow M, Adams NC, Gale NW, Iwasaki A, Flavell RA: Recognition of single-stranded RNA viruses by Toll-like receptor 7. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2004; 101: 5598–603 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Du X, Poltorak A, Wei Y, Beutler B: Three novel mammalian toll-like receptors: gene structure, expression, and evolution. Eur Cytokine Netw 2000; 11: 362–71 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liu J, Xu C, Hsu LC, Luo Y, Xiang R, Chuang TH: A five-amino-acid motif in the undefined region of the TLR8 ectodomain is required for species-specific ligand recognition. Mol Immunol 2010; 47: 1083–90 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bergstrom B, Aune MH, Awuh JA, Kojen JF, Blix KJ, Ryan L, Flo TH, Mollnes TE, Espevik T, Stenvik J: TLR8 Senses Staphylococcus aureus RNA in Human Primary Monocytes and Macrophages and Induces IFN-beta Production via a TAK1-IKKbeta-IRF5 Signaling Pathway. J Immunol 2015; 195: 1100–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bagnoli F, Fontana MR, Soldaini E, Mishra RP, Fiaschi L, Cartocci E, Nardi-Dei V, Ruggiero P, Nosari S, De Falco MG, Lofano G, Marchi S, Galletti B, Mariotti P, Bacconi M, Torre A, Maccari S, Scarselli M, Rinaudo CD, Inoshima N, Savino S, Mori E, Rossi-Paccani S, Baudner B, Pallaoro M, Swennen E, Petracca R, Brettoni C, Liberatori S, Norais N, Monaci E, Bubeck Wardenburg J, Schneewind O, O’Hagan DT, Valiante NM, Bensi G, Bertholet S, De Gregorio E, Rappuoli R, Grandi G: Vaccine composition formulated with a novel TLR7-dependent adjuvant induces high and broad protection against Staphylococcus aureus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2015; 112: 3680–5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zou L, Feng Y, Xu G, Jian W, Chao W: Splenic RNA and MicroRNA Mimics Promote Complement Factor B Production and Alternative Pathway Activation via Innate Immune Signaling. J Immunol 2016; 196: 2788–98 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Feng Y, Chen H, Cai J, Zou L, Yan D, Xu G, Li D, Chao W: Cardiac RNA induces inflammatory responses in cardiomyocytes and immune cells via Toll-like receptor 7 signaling. J Biol Chem 2015; 290: 26688–98 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Feng Y, Zou L, Yan D, Chen H, Xu G, Jian W, Cui P, Chao W: Extracellular MicroRNAs Induce Potent Innate Immune Responses via TLR7/MyD88-Dependent Mechanisms. J Immunol 2017; 199: 2106–2117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zou L, Feng Y, Li Y, Zhang M, Chen C, Cai J, Gong Y, Wang L, Thurman JM, Wu X, Atkinson JP, Chao W: Complement factor B is the downstream effector of TLRs and plays an important role in a mouse model of severe sepsis. J Immunol 2013; 191: 5625–35 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zou L, Chen HH, Li D, Xu G, Feng Y, Chen C, Wang L, Sosnovik DE, Chao W: Imaging Lymphoid Cell Death In Vivo During Polymicrobial Sepsis. Crit Care Med 2015; 43: 2303–12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mai SHC, Sharma N, Kwong AC, Dwivedi DJ, Khan M, Grin PM, Fox-Robichaud AE, Liaw PC: Body temperature and mouse scoring systems as surrogate markers of death in cecal ligation and puncture sepsis. Intensive Care Med Exp 2018; 6: 20 doi: 10.1186/s40635-018-0184-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim H, Hur M, Cruz DN, Moon HW, Yun YM: Plasma neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin as a biomarker for acute kidney injury in critically ill patients with suspected sepsis. Clin Biochem 2013; 46: 1414–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim S, Kim HJ, Ahn HS, Song JY, Um TH, Cho CR, Jung H, Koo HK, Park JH, Lee SS, Park HK: Is plasma neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin a predictive biomarker for acute kidney injury in sepsis patients? A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Crit Care 2016; 33:213–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang A, Cai Y, Wang PF, Qu JN, Luo ZC, Chen XD, Huang B, Liu Y, Huang WQ, Wu J, Yin YH: Diagnosis and prognosis of neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin for acute kidney injury with sepsis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Care 2016; 20: 41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tu Y, Wang H, Sun R, Ni Y, Ma L, Xv F, Hu X, Jiang L, Wu A, Chen X, Chen M, Liu J, Han F: Urinary netrin-1 and KIM-1 as early biomarkers for septic acute kidney injury. Ren Fail 2014; 36: 1559–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.van der Poll T, van de Veerdonk FL, Scicluna BP, Netea MG: The immunopathology of sepsis and potential therapeutic targets. Nat Rev Immunol 2017; 17: 407–420 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dominguez-Villar M, Gautron AS, de Marcken M, Keller MJ, Hafler DA: TLR7 induces anergy in human CD4(+) T cells. Nat Immunol 2015; 16: 118–28 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ghosn EE, Cassado AA, Govoni GR, Fukuhara T, Yang Y, Monack DM, Bortoluci KR, Almeida SR, Herzenberg LA, Herzenberg LA: Two physically, functionally, and developmentally distinct peritoneal macrophage subsets. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2010; 107: 2568–73 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Spor A, Koren O, Ley R: Unravelling the effects of the environment and host genotype on the gut microbiome. Nat Rev Microbiol 2011; 9: 279–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Singer M, Deutschman CS, Seymour CW, Shankar-Hari M, Annane D, Bauer M, Bellomo R, Bernard GR, Chiche JD, Coopersmith CM, Hotchkiss RS, Levy MM, Marshall JC, Martin GS, Opal SM, Rubenfeld GD, van der Poll T, Vincent JL, Angus DC: The Third International Consensus Definitions for Sepsis and Septic Shock (Sepsis-3). JAMA 2016; 315: 801–10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hotchkiss RS, Monneret G, Payen D: Sepsis-induced immunosuppression: from cellular dysfunctions to immunotherapy. Nat Rev Immunol 2013; 13: 862–74 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Isogawa M, Robek MD, Furuichi Y, Chisari FV: Toll-like receptor signaling inhibits hepatitis B virus replication in vivo. J Virol 2005; 79: 7269–72 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee J, Chuang TH, Redecke V, She L, Pitha PM, Carson DA, Raz E, Cottam HB: Molecular basis for the immunostimulatory activity of guanine nucleoside analogs: activation of Toll-like receptor 7. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2003; 100: 6646–51 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee J, Wu CC, Lee KJ, Chuang TH, Katakura K, Liu YT, Chan M, Tawatao R, Chung M, Shen C, Cottam HB, Lai MM, Raz E, Carson DA: Activation of anti-hepatitis C virus responses via Toll-like receptor 7. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2006; 103: 1828–33 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gosu V, Basith S, Kwon OP, Choi S: Therapeutic applications of nucleic acids and their analogues in Toll-like receptor signaling. Molecules 2012; 17: 13503–29 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fabbri M, Paone A, Calore F, Galli R, Gaudio E, Santhanam R, Lovat F, Fadda P, Mao C, Nuovo GJ, Zanesi N, Crawford M, Ozer GH, Wernicke D, Alder H, Caligiuri MA, Nana-Sinkam P, Perrotti D, Croce CM: MicroRNAs bind to Toll-like receptors to induce prometastatic inflammatory response. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2012; 109: E2110–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Weindel CG, Richey LJ, Bolland S, Mehta AJ, Kearney JF, Huber BT: B cell autophagy mediates TLR7-dependent autoimmunity and inflammation. Autophagy 2015; 11: 1010–24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Piper CJM, Wilkinson MGL, Deakin CT, Otto GW, Dowle S, Duurland CL, Adams S, Marasco E, Rosser EC, Radziszewska A, Carsetti R, Ioannou Y, Beales PL, Kelberman D, Isenberg DA, Mauri C, Nistala K, Wedderburn LR: CD19(+)CD24(hi)CD38(hi) B Cells Are Expanded in Juvenile Dermatomyositis and Exhibit a Pro-Inflammatory Phenotype After Activation Through Toll-Like Receptor 7 and Interferon-alpha. Front Immunol 2018; 9: 1372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lehmann SM, Kruger C, Park B, Derkow K, Rosenberger K, Baumgart J, Trimbuch T, Eom G, Hinz M, Kaul D, Habbel P, Kalin R, Franzoni E, Rybak A, Nguyen D, Veh R, Ninnemann O, Peters O, Nitsch R, Heppner FL, Golenbock D, Schott E, Ploegh HL, Wulczyn FG, Lehnardt S: An unconventional role for miRNA: let-7 activates Toll-like receptor 7 and causes neurodegeneration. Nat Neurosci 2012; 15: 827–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang Z, Ohto U, Shibata T, Krayukhina E, Taoka M, Yamauchi Y, Tanji H, Isobe T, Uchiyama S, Miyake K, Shimizu T: Structural Analysis Reveals that Toll-like Receptor 7 Is a Dual Receptor for Guanosine and Single-Stranded RNA. Immunity 2016; 45: 737–748 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Talreja J, Samavati L: K63-Linked Polyubiquitination on TRAF6 Regulates LPS-Mediated MAPK Activation, Cytokine Production, and Bacterial Clearance in Toll-Like Receptor 7/8 Primed Murine Macrophages. Front Immunol 2018; 9: 279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cushing L, Winkler A, Jelinsky SA, Lee K, Korver W, Hawtin R, Rao VR, Fleming M, Lin LL: IRAK4 kinase activity controls Toll-like receptor-induced inflammation through the transcription factor IRF5 in primary human monocytes. J Biol Chem 2017; 292: 18689–18698 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schoenemeyer A, Barnes BJ, Mancl ME, Latz E, Goutagny N, Pitha PM, Fitzgerald KA, Golenbock DT: The interferon regulatory factor, IRF5, is a central mediator of toll-like receptor 7 signaling. J Biol Chem 2005; 280: 17005–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Park CK, Xu ZZ, Berta T, Han Q, Chen G, Liu XJ, Ji RR: Extracellular microRNAs activate nociceptor neurons to elicit pain via TLR7 and TRPA1. Neuron 2014; 82: 47–54 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mukherjee P, Winkler CW, Taylor KG, Woods TA, Nair V, Khan BA, Peterson KE: SARM1, Not MyD88, Mediates TLR7/TLR9-Induced Apoptosis in Neurons. J Immunol 2015; 195: 4913–21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zou L, Feng Y, Chen YJ, Si R, Shen S, Zhou Q, Ichinose F, Scherrer-Crosbie M, Chao W: Toll-like receptor 2 plays a critical role in cardiac dysfunction during polymicrobial sepsis. Crit Care Med 2010; 38: 1335–42 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Feng Y, Zou L, Zhang M, Li Y, Chen C, Chao W: MyD88 and Trif signaling play distinct roles in cardiac dysfunction and mortality during endotoxin shock and polymicrobial sepsis. Anesthesiology 2011; 115: 555–67 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Koerner P, Traeger T, Mehmcke H, Cziupka K, Kessler W, Busemann A, Diedrich S, Hartmann G, Heidecke CD, Maier S: Stimulation of TLR7 prior to polymicrobial sepsis improves the immune control of the inflammatory response in adult mice. Inflamm Res 2011; 60: 271–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schrier RW, Wang W: Acute renal failure and sepsis. N Engl J Med 2004; 351: 159–69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nechemia-Arbely Y, Barkan D, Pizov G, Shriki A, Rose-John S, Galun E, Axelrod JH: IL-6/IL-6R axis plays a critical role in acute kidney injury. J Am Soc Nephrol 2008; 19: 1106–15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhang D, Xu J, Ren J, Ding L, Shi G, Li D, Dou H, Hou Y: Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells Induce Podocyte Injury Through Increasing Reactive Oxygen Species in Lupus Nephritis. Front Immunol 2018; 9: 1443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ermert D, Zychlinsky A, Urban C: Fungal and bacterial killing by neutrophils. Methods Mol Biol 2009; 470: 293–312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sonego F, Castanheira FV, Ferreira RG, Kanashiro A, Leite CA, Nascimento DC, Colon DF, Borges Vde F, Alves-Filho JC, Cunha FQ: Paradoxical Roles of the Neutrophil in Sepsis: Protective and Deleterious. Front Immunol 2016; 7: 155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Reddy RC, Standiford TJ: Effects of sepsis on neutrophil chemotaxis. Curr Opin Hematol 2010; 17: 18–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Alves-Filho JC, Freitas A, Souto FO, Spiller F, Paula-Neto H, Silva JS, Gazzinelli RT, Teixeira MM, Ferreira SH, Cunha FQ: Regulation of chemokine receptor by Toll-like receptor 2 is critical to neutrophil migration and resistance to polymicrobial sepsis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2009; 106: 4018–23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chishti AD, Shenton BK, Kirby JA, Baudouin SV: Neutrophil chemotaxis and receptor expression in clinical septic shock. Intensive Care Med 2004; 30: 605–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Arraes SM, Freitas MS, da Silva SV, de Paula Neto HA, Alves-Filho JC, Auxiliadora Martins M, Basile-Filho A, Tavares-Murta BM, Barja-Fidalgo C, Cunha FQ: Impaired neutrophil chemotaxis in sepsis associates with GRK expression and inhibition of actin assembly and tyrosine phosphorylation. Blood 2006; 108: 2906–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rios-Santos F, Alves-Filho JC, Souto FO, Spiller F, Freitas A, Lotufo CM, Soares MB, Dos Santos RR, Teixeira MM, Cunha FQ: Down-regulation of CXCR2 on neutrophils in severe sepsis is mediated by inducible nitric oxide synthase-derived nitric oxide. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2007; 175: 490–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Secher T, Vasseur V, Poisson DM, Mitchell JA, Cunha FQ, Alves-Filho JC, Ryffel B: Crucial role of TNF receptors 1 and 2 in the control of polymicrobial sepsis. J Immunol 2009; 182: 7855–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kaufmann SHE, Dorhoi A: Molecular Determinants in Phagocyte-Bacteria Interactions. Immunity 2016; 44: 476–491 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Vijay-Kumar M, Aitken JD, Carvalho FA, Cullender TC, Mwangi S, Srinivasan S, Sitaraman SV, Knight R, Ley RE, Gewirtz AT: Metabolic syndrome and altered gut microbiota in mice lacking Toll-like receptor 5. Science 2010; 328: 228–31 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.