Abstract

The subcutaneous administration route is widely used to administer different types of drugs given its high bioavailability and rapid onset of action. However, the sensation of pain at the injection site might reduce patient adherence. Apart from a direct effect of the drug itself, several factors can influence the sensation of pain: needle features, injection site, volume injected, injection speed, osmolality, viscosity and pH of formulation, as well as the kind of excipients employed, including buffers and preservatives. Short and thin needles, conveniently lubricated and with sharp tips, are generally used to minimize pain, although the anatomic injection site (abdomen versus thigh) also affects the sensation of pain. Large subcutaneous injection volumes are associated with pain. In this sense, the maximum volume generally accepted is around 1.5 ml, although volumes of up to 3 ml are well tolerated when injected in the abdomen. Injected volumes of up to 0.5–0.8 ml are not expected to increase substantially the pain produced by the needle insertion. Ideally, injectable products should be formulated as isotonic solutions (osmolality of about 300 mOsm/kg) and no more than 600 mOs/kg have to be used in order to prevent pain. A pH close to the physiological one is recommended to minimize pain, irritation, and tissue damage. Buffers are frequently added to parenteral formulations to optimize solubility and stability by adjusting the pH; however, their strength should be kept as low as possible to avoid pain upon injection. The data available recommend the concentration of phosphate buffer be limited to 10 mM and that the concentration of citrate buffer should be lower than 7.3 mM to avoid an increased sensation of pain. In the case of preservatives, which are required in multiple-dose preparations, m-cresol seems to be more painful than benzyl alcohol and phenol.

Funding: Sandoz SA.

Keywords: Buffer composition, Pain, Pharmacology, Preservatives, Subcutaneous injection, Volume injected

Introduction

Biopharmaceuticals, such as vaccines, heparin, insulin, growth hormone, hematopoietic growth factors, interferons, monoclonal antibodies, etc., are generally incompatible with oral delivery. Consequently, they have to be administered parenterally, by means of intravenous (IV), intramuscular (IM), or, most commonly, subcutaneous (SC) injection. The SC route is also used for the administration of local anesthetics and drugs used in palliative care, such as fentanyl and morphine.

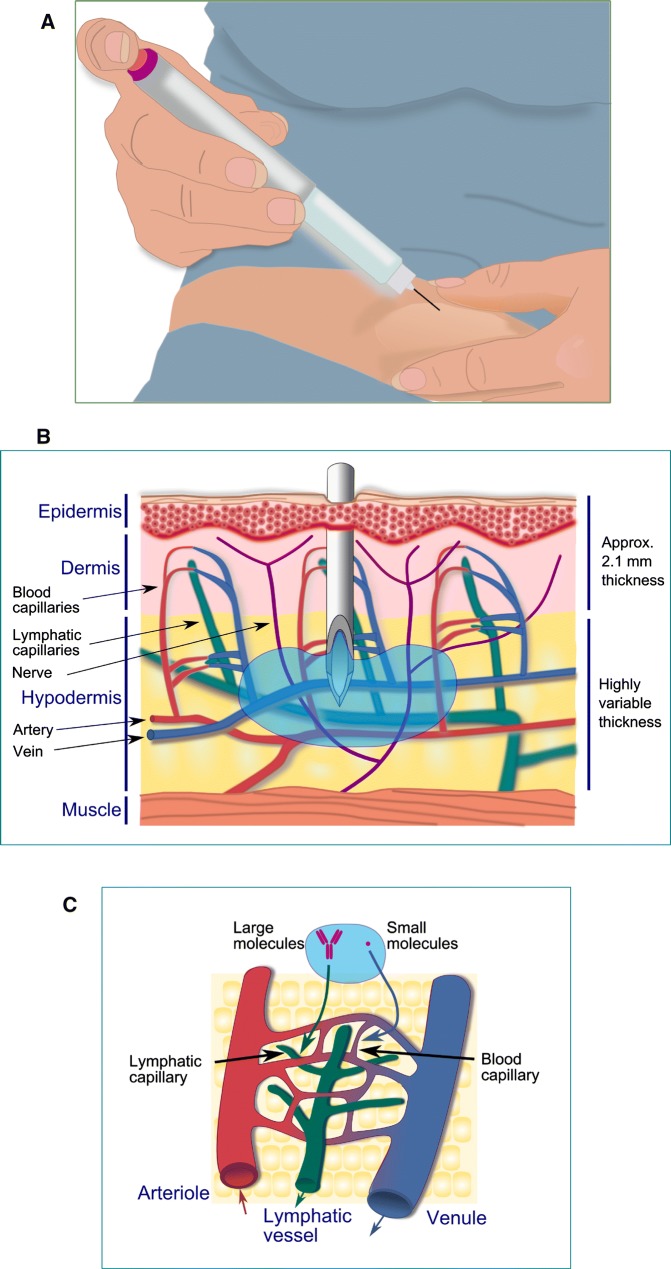

From a pharmacokinetic point of view, parenteral routes can be considered near-ideal ways of administration due to the high bioavailability and rapid onset of action usually obtained. In the case of IV administration, the entire dose reaches the systemic circulation and an immediate physiological response can be achieved, whereas IM and SC administrations involve an absorption process from the injection site, which leads to a delayed response, since drug molecules have to diffuse in the interstitial space in order to reach the capillaries (i.e., to be absorbed). This absorption process can be influenced by various factors either physicochemical (such as molecular size, electrostatic charge, and hydrophilicity) or physiological (such as those arising from the interaction of the administered drug with endogenous compounds, blood, and lymph flows and/or the influence of tissue hydration). Molecules larger than about 16 kDa, such as monoclonal antibodies, are mostly absorbed into lymphatic capillaries whereas those under 1 kDa are preferentially absorbed into blood capillaries [1]. There are remarkable advantages of SC injections over the other injection types, since skilled personnel are not required, in contrast to IV and IM administrations, the injections are less painful, the risk of infection is lower in SC than in IV injections, and, if this occurs, the infection is generally limited to a local infection rather than a systemic infection. Furthermore, SC injections offer a broader range of alternative sites than IM injections for those patients requiring multiple doses [2].

Notwithstanding the aforesaid advantages of the SC route, patients’ adherence to treatments based on SC injections can be compromised by the frequency of injections and injection site reactions, including pain, mainly when the consequence of nonadherence is not immediately life-threatening [3]. In general, decreasing the frequency of administrations improves adherence [4, 5], but the subjective pain at the injection site can be the determinant for adherence even in case of long dosing intervals. Besides a direct effect of the drug itself, several factors may be associated with the sensation of pain after SC injections: needle features, injection technique and site, volume injected, injection speed, osmolality, viscosity and pH of formulation, as well as the kind of excipients in the formulation, including buffers and preservatives. Although in vitro methods, based on subcutaneous and muscle tissues of porcine, have been developed to evaluate the effect of injection conditions on the drug permeation in tissues [6], their use to predict sensation of pain in patients is limited because of the absence of functional sensory nerves. The present review addresses the role of the above factors in the subjective sensation of pain in individuals receiving SC injections.

Methods

The present review is based on literature search using Pubmed, MEDLINE, Google, and Google Scholar databases. Only articles written in English were included and the keywords employed were “pain” and “subcutaneous” combined with “needle length”, “needle diameter”, “injection site”, “injection procedure”, “injection volume”, “injection speed”, “osmolality”, “viscosity”, “buffer”, or “preservative”. In addition, the search was limited according to time, selecting those articles published from 1990 to the present. Studies performed in animals were not included. A total of 188 articles were identified and reviewed, and both their text and references were analyzed. The most relevant articles were used to write this review.

This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Results

Needle Features, Injection Site, and Injection Procedure

The main factors of the needles used for SC administration capable of playing a role in the sensation of pain are length, diameter, bluntness of the needle tip, bevel type, and lubricity.

It is generally assumed that needles of a shorter and smaller diameter provoke less painful insertions, bleeding, and bruising [7, 8]. The needle needs to be long enough to ensure that the medication reaches the hypodermis but not so long that this is injected in the underlying muscle. Muscle is more vascularized than SC tissue and the absorption of drugs is faster after an IM injection, which leads to modified response as compared to that obtained after SC injection. In this sense, the IM injection of insulin leads to higher fluctuations in sugar control, an increased risk of hypoglycemia and more pain than the SC administration [9, 10]. The available needle lengths for SC injection are 4–12.7 mm for pens and 6–12.7 mm for syringes [11], and given the highly variable thickness of hypodermis [12–15], summarized in Table 1, the adequate needle length should be selected according to the specific population to be administered in order to reduce the risk of IM injection. In this respect, it has been recommended to use needle lengths in the 4–8 mm range in the case of adults and in the 4–6 mm range for children [10]. A skin fold is generally recommended, specially for needles in the 6–12.7 mm range, although it is not necessary when a very short needle (4 mm length) is used (Fig. 1).

Table 1.

Skin (epidermis + dermis) and subcutaneous tissue thickness (ST and SCT, respectively) obtained in different anatomical zones of the human body by the indicated studies

| Arm | Abdomen | Thigh | References | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ST | SCT | ST | SCT | ST | SCT | ||

| Adults | |||||||

| Both sexes | 2.23 ± 0.44 | 10.77 ± 5.62 | 2.15 ± 0.42 | 13.92 ± 7.26 | 1.87 ± 0.39 | 10.35 ± 5.65 | [21]a |

| Male | 2.12 ± 0.39 | 2.81 ± 1.16 | 2.35 ± 0.43 | 9.83 ± 6.67 | 2.11 ± 0.37 | 3.97 ± 2.76 | [1]a |

| 1.92 ± 0.31 | 3.03 ± 2.27 | 2.36 ± 0.42 | 11.68 ± 9.19 | 1.97 ± 0.33 | 3.48 ± 2.35 | [1]b | |

| – | – | 2.10 (1.99–2.21) | 17.88 (15.93–19.83) | 1.89 (1.78–2.01) | 9.84 (8.21–11.48) | [13]a,c | |

| 2.14 ± 0.31 | 4.06 ± 1.79 | 2.37 ± 0.36 | 7.75 ± 5.03 | – | – | [43]a | |

| Female | 2.08 ± 0.44 | 9.14 ± 7.36 | 2.31 ± 0.42 | 20.19 ± 9.73 | 2.12 ± 0.43 | 10.33 ± 7.39 | [1]a |

| 1.85 ± 0.35 | 7.44 ± 5.87 | 2.27 ± 0.43 | 16.71 ± 9.46 | 1.86 ± 0.44 | 9.64 ± 6.44 | [1]b | |

| – | – | 1.99 (1.89–2.09) | 21.26 (19.54–22.99) | 1.65 (1.55–1.76) | 17.68 (16.23–19.12) | [13]a,c | |

| 1.84 ± 0.29 | 7.19 ± 2.56 | 2.20 ± 0.36 | 13.07 ± 7.03 | – | – | [43]a | |

| Children and adolescents | |||||||

| Male | – | – | 1.89 (1.75–2.03) | 9.13 (7.75–10.51) | 1.60 (1.50–1.70) | 7.68 (6.25–9.12) | [13]a,c,d |

| Female | – | – | 1.83 (1.68–1.97) | 13.06 (11.70–14.42) | 1.57 (1.47–1.68) | 13.39 (11.97–14.82) | [13]a,c,e |

Data (in millimeters) are the mean value ± standard deviation or the mean value (95% confidence interval)

aDiabetic patients

bHealthy volunteers

cIn this study, ST refers only to dermis

dAge 6.0–18.0 years

eAge 6.0–19.0 years

Fig. 1.

Subcutaneous self-injection of a medicinal product in the anterior abdomen (a) using the “pinch-up” technique. The mean skin thickness is around 2.1 mm in the anatomic zones commonly used for subcutaneous injections (b); however, the target tissue (hypodermis) shows a wide variability in thickness. The absorption route of the administered molecules depends on their size (c), with molecules larger than about 16 kDa being mostly absorbed into lymphatic capillaries and those smaller than 1 kDa into blood capillaries [48]

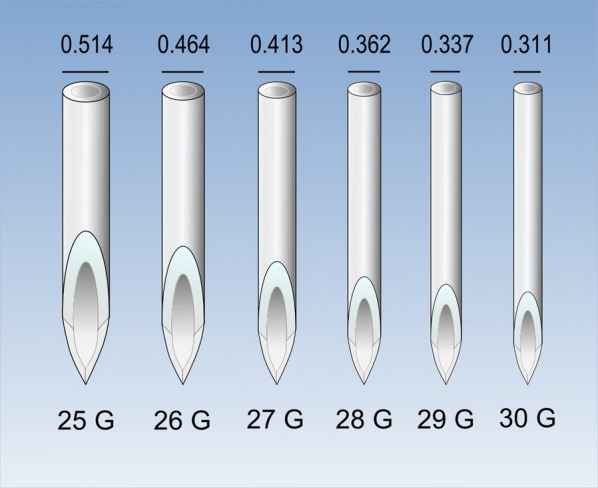

The needle diameter (Fig. 2) is another factor commonly associated with the sensation of pain, with less frequent painful needle insertions in the case of needles with smaller diameters [16]. However, the diameter ranges with differences in the frequency of pain are not clear, since painful insertions decreasing from 63% to 31% in the 23–32 G range have been reported [16] whereas other authors found no differences in injection pain when comparing needles in narrower ranges, such as 26–30 G [17, 18].

Fig. 2.

Relative diameter of needles according to the gauge system (G). Values in the upper part indicate the external diameter in millimeters

In addition, the sharpness and geometry of tip needles may also affect the pain sensation. In this sense, it has been reported that 5-bevel needle tips reduce the average penetration force in a skin substitute by 23% in comparison to similar 3-bevel tips [19]. In the same study, the 5-bevel needle tip geometry was perceived by diabetic patients as less painful.

Needle lubrication is usually performed through the use of silicone coating to decrease resistance of insertion and thereby minimizing injection pain. The most common silicone oil used in medical applications is polydimethylsiloxane, which is available in different viscosities and can be used to coat syringe barrels and needles [20]. The goal of syringe barrel siliconization is to allow the plunger to glide smoothly within the barrel, whereas the silicon coating of the needle prevents it sticking to the skin. Although silicone oil is generally considered inert and insoluble in water, it can induce the formation of aggregates in formulations of protein-based drugs [21, 22] which can increase the severity of immune responses [20].

When performing SC injections, the recommended injection angle is around 45° or 90° depending on needle length and the amount of subcutaneous tissue at the injection site [23]. A 45° injection angle is particularly recommended when needles of 8 mm length or longer are used [10]. When the injection is performed with an angle of approximately 45°, the needle should be placed bevel up to reduce pain [24]. The anatomic injection site has also been associated with a different degree of pain and thigh injections have been rated more painful than injections in the abdomen [25, 26].

Nowadays, new non-injectable subcutaneous systems and technologies are being developed, ensuring virtually painless and highly efficient drug delivery. These devices require a power source which may be obtained either physically or by the application of some force. They have several advantages such as that are easy to use, store, and dispose, and do not require any expert supervision or handling. In fact, some systems have been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for subcutaneous administration and are available commercially (Biojector 2000, Viajet 3, Tev-Tropin®, Sumavel® DosePro™, Bioject® ZetaJet™, Jupiter Jet™) [27].

The temperature of the solution to be injected also affects to the sensation of pain. Most biopharmaceuticals are stored at 2–8 °C and they should be kept at room temperature for about 30 min before administration in order to avoid the pain provoked by the injection of a cold solution [28].

Volume, Speed, Osmolality, and Viscosity

The maximum volume generally accepted for an SC injection is around 1.5 ml [29], although higher volumes (of up to 4 ml) can be administered if necessary [30]. In spite of the fact that large SC injected volumes have been generally associated with pain and adverse events at the injection site [29], the published data is somewhat conflicting. Thus, an earlier study [31] compared different volumes of NaCl 0.9% injected in the thigh of volunteers and found that volumes of 1 ml and 1.5 ml caused more pain than volumes of 0.5 ml or less. However, another study concluded that solutions of up to 3 ml were well tolerated without pain when injected in the abdomen of healthy volunteers [32]. The discrepancies between both studies could be due, at least in part, to the different anatomic injection site employed, since, as indicated above, thigh injections have been rated more painful than injections in the abdomen [25, 26]. The studies by Heise et al. [26] and Zijlstra et al. [25] were conducted in diabetic patients which were injected in the thigh and abdomen with different volumes of saline combined with different injection speeds. Although it was observed, in both studies, that the thigh injection was more painful than the injection in the abdomen, the sensation of pain did not change for injected volumes in the range of 0–0.8 ml, neither in the thigh nor in the abdomen. Considering the available literature on the effect of the volume on the sensation of pain after SC injections, injected volumes of up to 0.5–0.8 ml are expected not to substantially increase the pain produced by the needle insertion.

Ideally, injectable products should be formulated as isotonic solutions (osmolality of about 300 mOsm/kg) [33]. However, it is common practice to administer hypertonic solutions to reduce the total volume injected. The degree of hypertonicity has been related to the sensation of pain and an upper limit of 600 mOsm/kg has been proposed to minimize hypertonicity-induced pain [34].

Injection speed seems to have no impact on injection-related pain [25, 26, 35]. In a study performed with 82 diabetic patients in whom different injection speeds of saline were tested (150, 300, and 450 µl/s), no differences in perceived injection pain between speeds were found [26]. A similar conclusion was obtained with the administration of 4.5 ml of a lidocaine solution on the abdomen of healthy volunteers using SC injections lasting 15 s (300 µl/s), 30 s (150 µl/s), and 45 s (100 µl/s), with no differences in the sensation of pain between the three injection speeds [35].

A very low viscosity of the injected solution has also been associated with an increased sensation of pain. In fact, in a study comparing the pain perceived after the injections of three different fluid viscosities (1, 8–10, and 15–20 cP) it was observed that high viscosity injections (up to 15–20 cP) were less painful and, consequently, the most easily tolerated ones [32].

pH and Buffer Composition

A general recommendation is to formulate parenteral medicinal products with a pH close to the physiological pH to minimize pain, irritation, and tissue damage, except when stability or solubility considerations preclude this. It has been found that pH values above 9 are related to tissue necrosis, whereas values lower than 3 can cause pain and phlebitis [33].

Buffers (Table 2) are added to parenteral formulations to adjust the pH [33, 36, 37] with the aim of optimizing solubility and stability, and are typically used in the 10–100 mM range [33]. In this context, the most common buffers used in parenteral formulations are citrate, phosphate, and acetate [33].

Table 2.

Buffers used in parenteral preparations and approximate buffering range

| Buffer | pH range |

|---|---|

| Glutamate | 2.0–5.3 |

| Tartrate | 2.0–5.3 |

| Lactate | 2.1–4.1 |

| Citrate | 2.1–6.2 |

| Malate | 2.4–6.1 |

| Gluconate | 2.6–4.6 |

| Ascorbate | 3.0–5.0 |

| Maleate | 3.0–5.0 |

| Phosphate | 3.0–8.0 |

| Succinate | 3.2–6.6 |

| Acetate | 3.8–5.8 |

| Bicarbonate | 4.0–11.0 |

| Aspartate | 5.0–5.6 |

| Histidine | 5.0–6.5 |

| Benzoate | 6.0–7.0 |

| Tromethamine | 7.1–9.1 |

| Diethanolamine | 8.0–10.0 |

| Ammonium | 8.25–10.25 |

| Glycine | 8.8–10.8 |

There are a few publish articles that study the relationship between buffer composition and/or concentration and sensation of pain after SC injection. In this sense, formulations containing different phosphate buffer concentrations at pH values from 6 to 7 have been compared [38]. The lowest discomfort at the injection site was obtained with 10 mM phosphate at pH 7. Injection of 50 mM phosphate at pH 6 was more painful than 10 mM phosphate. However, there were no differences in pain when 10 mM phosphate at pH 6, 10 mM phosphate at pH 7, and 50 mM phosphate at pH 7 were compared. The authors concluded that for SC injections at non-physiological pH, the buffer strength should be kept as low as possible to avoid pain upon injection.

Citrate buffer is commonly used in parenteral formulations at concentrations in the range 5–15 mM, and it is assumed that increasing the concentration to more than 50 mM can result in excessive pain upon SC injection [36]. However, some studies have shown that citrate concentrations lower than 50 mM may also be painful. Thus, in a study carried out to identify the pain-causing substance in epoetin alfa (EPO-alfa) preparations, the authors found that citrate buffer (approx. 23 mM) was the component responsible of the local pain experienced after the SC administration of EPO-alfa [39]. In another study, the perception of pain after SC injection of two different commercially available solutions for dispensing recombinant human growth hormone containing citrate (10 mM) or histidine (4.4 mM) was evaluated in healthy volunteers [40]. The pH was similar for both buffers, 6.15 for histidine and 6.00 for citrate, as well as the preservative concentration (3 mg/ml and 2.5 mg/ml of phenol, respectively). The author of this study concluded that the use of citrate as a buffer caused more pain immediately after SC injection than the solution with histidine. However, there was no difference between both buffers 2 min after injection.

The use of citrate to buffer adalimumab solutions has also been related to a higher sensation of pain [41, 42], although given the design of some of these studies it is difficult to attribute the differences in the injection site-related pain to the content in citrate buffer. Thus, the adalimumab preparation containing citrate buffer (7.3 mM) differed from the citrate-free one in volume (0.8 ml vs 0.4 ml), needle diameter (27 G vs 29 G) of prefilled syringes used for the administrations, and excipients [42]. In this context, some of the new formulations of adalimumab have removed or substantially lowered the concentration of the citrate buffer to a residual concentration of 1.2 mM [43, 44], which should minimize or prevent pain potentially associated with this buffer. Only a low percentage of adalimumab-treated patients versus placebo had reported pain related to injection in adalimumab clinical trials [45–47], and only one reported dropout specifically related to injection-site pain [48] was found in our literature search.

A recent report from the UK National Health Service (NHS) based on 6 months’ usage of adalimumab biosimilars in 35,000 patients in the UK (63.6% of patients that were receiving adalimumab) has analyzed the reported discomfort at the injection site. This discomfort has been reported with all products and has not been directly linked to the citrate content of the injection. Other documented parameters that have been shown to influence the discomfort include injection technique, speed of injection, and temperature of the injection [49].

It has been reported that buffering local anesthetic solutions with sodium bicarbonate reduces local pain. Lidocaine and bupivacaine solutions are acidic and cause pain upon injection, which can be mitigated by increasing the pH to 7 with sodium bicarbonate [50]. In addition, buffering local anesthetic solutions with sodium bicarbonate improves onset time, duration of action, and anesthetic effect, since local anesthetic activity is strongly pH-dependent [51].

In summary, the available data about the effect of buffers on the sensation of pain suggest that, in some cases, it is a consequence of the particular drug–buffer combination, as occurs in the case of bicarbonate and local anesthetics in which the buffering capacity of bicarbonate at pH 7 increases the activity of the anesthetics, thus reducing pain associated with the SC injection [51]. In other cases, the concentration of the buffer is associated with increased pain, as occurs when phosphate is used at concentrations higher than 10 mM and pH 6 (but not at pH 7) [38] or when citrate is used at concentrations of 7.3–10 mM [40, 42]. These data recommend the concentration of phosphate be limited to 10 mM and the concentration of citrate be lower than 7.3 mM in order to avoid a potential increased sensation of pain as compared to that produced by the insertion of the needle.

Preservatives

Multiple-dose preparations require antimicrobial preservatives to inhibit the growth of microorganisms that may be introduced from repeatedly withdrawing individual doses.

A review by Meyer et al. [52] shows that phenol and benzyl alcohol are the two most common antimicrobial preservatives used in peptide and protein products, while phenoxyethanol is the most frequently used preservative in vaccines. Benzyl alcohol or a combination of methylparaben and propylparaben is generally used in small molecule parenteral formulations.

The local discomfort and pain at the injection site of some growth hormone preparations have been associated with the preservatives used in the formulations [53]. The sensation of pain was similar between formulations containing phenol (3 mg/ml) and benzyl alcohol (3–9 mg/ml), whereas m-cresol (9 mg/ml) was associated with more painful injections than benzyl alcohol.

Conclusion

Multiple factors related to the injection technique and the composition of the injected solution can affect the sensation of pain after SC injections. Injected volumes lower than 0.8 ml, drug solutions at room temperature, and injection in the abdomen are injection technique-dependent factors meant to reduce pain. Ideally, injectable products should be formulated as isotonic solutions with a pH close to the physiological one. Solution osmolality should be lower than 600 mOs/kg in order to prevent pain. There are not very solid data attributing pain in injection site to buffers, and several associated confounding factors in the studies make it difficult to reach conclusions. On the basis of the data, we would recommend the concentration of phosphate to be limited to 10 mM and the concentration of citrate be lower than 7.3 mM. Preservatives, which are required in the case of multiple-dose preparations, can increase the sensation of pain. In preparations of growth hormone, the preservative m-cresol has been reported to be more painful than phenol and benzyl alcohol.

Acknowledgements

Funding

This review, the Rapid Service, and Open Access Fees were funded by Sandoz SA.

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Disclosures

Rafael Martinez is an employee of Sandoz SA. Teodora Festini is an employee of Sandoz SA. José-Esteban Peris has acted as a consultant for Sandoz, Qualicaps Europe, Schering-Plough, Dupont Pharma and Belmac Laboratories. Iris Usach has nothing to disclose.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Footnotes

Enhanced Digital Features

To view enhanced digital features for this article go to 10.6084/m9.figshare.9861800.

References

- 1.Viola M, Sequeira J, Seica R, et al. Subcutaneous delivery of monoclonal antibodies: how do we get there? J Control Release. 2018;286:301–314. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2018.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Haller MF. Converting intravenous dosing to subcutaneous dosing with recombinant human hyaluronidase. Pharm Technol. 2007;31(10):118–132. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bolge SC, Goren A, Tandon N. Reasons for discontinuation of subcutaneous biologic therapy in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis: a patient perspective. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2015;9:121–131. doi: 10.2147/PPA.S70834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ringe JD, Farahmand P. Improved real-life adherence of 6-monthly denosumab injections due to positive feedback based on rapid 6-month BMD increase and good safety profile. Rheumatol Int. 2014;34(5):727–732. doi: 10.1007/s00296-012-2663-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Poulos C, Kinter E, Yang JC, Bridges JF, Posner J, Reder AT. Patient preferences for injectable treatments for multiple sclerosis in the United States: a discrete-choice experiment. Patient. 2016;9(2):171–180. doi: 10.1007/s40271-015-0136-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim H, Park H, Lee SJ. Effective method for drug injection into subcutaneous tissue. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):9613. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-10110-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kreugel G, Beijer H, Kerstens M, Ter Maaten J, Sluiter W, Boot B. Influence of needle size for subcutaneous insulin administration on metabolic control and patient acceptance. Eur Diabetes Nurs. 2007;4(2):51–55. doi: 10.1002/edn.77. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guo X, Wang W. Challenges and recent advances in the subcutaneous delivery of insulin. Expert Opin Drug Deliv. 2017;14(6):727–734. doi: 10.1080/17425247.2016.1232247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Karges B, Boehm BO, Karges W. Early hypoglycaemia after accidental intramuscular injection of insulin glargine. Diabet Med. 2005;22(10):1444–1445. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2005.01654.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Australian Diabetes Educators Association (ADEA). Clinical guiding principles for subcutaneous injection technique. 2015. https://www.adea.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/Injection-Technique-Final-digital-version2.pdf. Accessed Nov 2018.

- 11.Hirsch L, Byron K, Gibney M. Intramuscular risk at insulin injection sites–measurement of the distance from skin to muscle and rationale for shorter-length needles for subcutaneous insulin therapy. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2014;16(12):867–873. doi: 10.1089/dia.2014.0111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gibney MA, Arce CH, Byron KJ, Hirsch LJ. Skin and subcutaneous adipose layer thickness in adults with diabetes at sites used for insulin injections: implications for needle length recommendations. Curr Med Res Opin. 2010;26(6):1519–1530. doi: 10.1185/03007995.2010.481203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Akkus O, Oguz A, Uzunlulu M, Kizilgul M. Evaluation of skin and subcutaneous adipose tissue thickness for optimal insulin injection. J Diabetes Metab. 2012;3(8):2. doi: 10.4172/2155-6156.1000216. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Derraik JG, Rademaker M, Cutfield WS, et al. Effects of age, gender, BMI, and anatomical site on skin thickness in children and adults with diabetes. PLoS One. 2014;9(1):e86637. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0086637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sim KH, Hwang MS, Kim SY, Lee HM, Chang JY, Lee MK. The appropriateness of the length of insulin needles based on determination of skin and subcutaneous fat thickness in the abdomen and upper arm in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Metab J. 2014;38(2):120–133. doi: 10.4093/dmj.2014.38.2.120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Arendt-Nielsen L, Egekvist H, Bjerring P. Pain following controlled cutaneous insertion of needles with different diameters. Somatosens Mot Res. 2006;23(1–2):37–43. doi: 10.1080/08990220600700925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hanas R, Lytzen L, Ludvigsson J. Thinner needles do not influence injection pain, insulin leakage or bleeding in children and adolescents with type 1 diabetes. Pediatr Diabetes. 2000;1(3):142–149. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-5448.2000.010305.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Robb DM, Kanji Z. Comparison of two needle sizes for subcutaneous administration of enoxaparin: effects on size of hematomas and pain on injection. Pharmacotherapy. 2002;22(9):1105–1109. doi: 10.1592/phco.22.13.1105.33510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hirsch L, Gibney M, Berube J, Manocchio J. Impact of a modified needle tip geometry on penetration force as well as acceptability, preference, and perceived pain in subjects with diabetes. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2012;6(2):328–335. doi: 10.1177/193229681200600216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Petersen C, Zeis B. Syringe siliconisation trends, methods and analysis procedures. Int Pharm Ind. 2015;7(2):78–84. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jones LS, Kaufmann A, Middaugh CR. Silicone oil induced aggregation of proteins. J Pharm Sci. 2005;94(4):918–927. doi: 10.1002/jps.20321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thirumangalathu R, Krishnan S, Ricci MS, Brems DN, Randolph TW, Carpenter JF. Silicone oil- and agitation-induced aggregation of a monoclonal antibody in aqueous solution. J Pharm Sci. 2009;98(9):3167–3181. doi: 10.1002/jps.21719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cooper K, Gosnell K. Foundations of nursing. St. Louis: Elsevier; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Candiotti K, Rodriguez Y, Koyyalamudi P, Curia L, Arheart KL, Birnbach DJ. The effect of needle bevel position on pain for subcutaneous lidocaine injection. J Perianesth Nurs. 2009;24(4):241–243. doi: 10.1016/j.jopan.2009.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zijlstra E, Jahnke J, Fischer A, Kapitza C, Forst T. Impact of injection speed, volume, and site on pain sensation. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2018;12(1):163–168. doi: 10.1177/1932296817735121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Heise T, Nosek L, Dellweg S, et al. Impact of injection speed and volume on perceived pain during subcutaneous injections into the abdomen and thigh: a single-centre, randomized controlled trial. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2014;16(10):971–976. doi: 10.1111/dom.12304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ravi AD, Sadhna D, Nagpaal D, Chawla L. Needle free injection technology: a complete insight. Int J Pharm Investig. 2015;5(4):192–199. doi: 10.4103/2230-973X.167662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.So J. Improving patient compliance with biopharmaceuticals by reducing injection-associated pain. J Mucopolysacch Rare Dis. 2015;1(1):15–18. doi: 10.19125/jmrd.2015.1.1.15. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mathaes R, Koulov A, Joerg S, Mahler HC. Subcutaneous injection volume of biopharmaceuticals-pushing the boundaries. J Pharm Sci. 2016;105(8):2255–2259. doi: 10.1016/j.xphs.2016.05.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.European Medicines Agency. Vidaza, INN-azacitidine. 2013. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/vidaza-epar-product-information_en.pdf. Accessed Nov 2018.

- 31.Jorgensen JT, Romsing J, Rasmussen M, Moller-Sonnergaard J, Vang L, Musaeus L. Pain assessment of subcutaneous injections. Ann Pharmacother. 1996;30(7–8):729–732. doi: 10.1177/106002809603000703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Berteau C, Filipe-Santos O, Wang T, Rojas HE, Granger C, Schwarzenbach F. Evaluation of the impact of viscosity, injection volume, and injection flow rate on subcutaneous injection tolerance. Med Devices (Auckl) 2015;8:473–484. doi: 10.2147/MDER.S91019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Broadhead J, Gibson M. Parenteral dosage forms. In: Gibson M, editor. Pharmaceutical preformulation and formulation. New York: Informa healthcare; 2009. pp. 325–347. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang W. Tolerability of hypertonic injectables. Int J Pharm. 2015;490(1–2):308–315. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2015.05.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tangen LF, Lundbom JS, Skarsvag TI, et al. The influence of injection speed on pain during injection of local anaesthetic. J Plast Surg Hand Surg. 2016;50(1):7–9. doi: 10.3109/2000656X.2015.1058269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nema S, Brendel RJ. Excipients for parenteral dosage forms: regulatory considerations and controls. In: Nema S, Ludwig JD, editors. Dosage forms: parenteral medications. Vol 3: regulations, validation and the future. New York: Informa Healthcare; 2010. pp. 109–134. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Botempo JA. Formulation development. In: Bontempo JA, editor. Development of biopharmaceutical parenteral dosage forms. New York: Informa Healthcare; 2007. pp. 109–142. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fransson J, Espander-Jansson A. Local tolerance of subcutaneous injections. J Pharm Pharmacol. 1996;48(10):1012–1015. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-7158.1996.tb05892.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Frenken LA, van Lier HJ, Jordans JG, et al. Identification of the component part in an epoetin alfa preparation that causes pain after subcutaneous injection. Am J Kidney Dis. 1993;22(4):553–556. doi: 10.1016/S0272-6386(12)80928-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Laursen T, Hansen B, Fisker S. Pain perception after subcutaneous injections of media containing different buffers. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2006;98(2):218–221. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-7843.2006.pto_271.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gely C, Marin L, Gordillo J, et al. Impact of pain due to subcutaneous administration of a biological drug. J Crohn’s Colitis. 2018;12:S582–S583. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjx180.1046. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nash P, Vanhoof J, Hall S, et al. Randomized crossover comparison of injection site pain with 40 mg/0.4 or 0.8 ml formulations of adalimumab in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatol Ther. 2016;3(2):257–270. doi: 10.1007/s40744-016-0041-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Food and Drug Administration. Hyrimoz®. Prescribing information. 2018. https://s3-us-west-2.amazonaws.com/drugbank/fda_labels/DB00051.pdf?1543522358. Accessed Oct 2018.

- 44.Food and Drug Administration. Humira®. Prescribing information. 2016. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2018/125057s410lbl.pdf. Accessed Oct 2018.

- 45.Weinblatt ME, Keystone EC, Furst DE, et al. Adalimumab, a fully human anti-tumor necrosis factor alpha monoclonal antibody, for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis in patients taking concomitant methotrexate: the ARMADA trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;48(1):35–45. doi: 10.1002/art.10697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sandborn WJ, Colombel JF, D’Haens G, et al. One-year maintenance outcomes among patients with moderately-to-severely active ulcerative colitis who responded to induction therapy with adalimumab: subgroup analyses from ULTRA 2. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2013;37(2):204–213. doi: 10.1111/apt.12145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hanauer SB, Sandborn WJ, Rutgeerts P, et al. Human anti-tumor necrosis factor monoclonal antibody (adalimumab) in Crohn’s disease: the CLASSIC-I trial. Gastroenterology. 2006;130(2):323–333. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.11.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Blauvelt A, Lacour JP, Fowler JF, Jr, et al. Phase III randomized study of the proposed adalimumab biosimilar GP2017 in psoriasis: impact of multiple switches. Br J Dermatol. 2018;179(3):623–631. doi: 10.1111/bjd.16890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.NHS. Regional medicines optimisation committee briefing, best value biologicals: adalimumab update 6. July 2019. https://www.sps.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/Adalimumab-RMOC-Briefing-6.pdf. Accessed 12 Sep 2019.

- 50.Best CA, Best AA, Best TJ, Hamilton DA. Buffered lidocaine and bupivacaine mixture—the ideal local anesthetic solution? Plast Surg (Oakv) 2015;23(2):87–90. doi: 10.1177/229255031502300206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Quaba O, Huntley JS, Bahia H, McKeown DW. A users guide for reducing the pain of local anaesthetic administration. Emerg Med J. 2005;22(3):188–189. doi: 10.1136/emj.2003.012070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Meyer BK, Ni A, Hu B, Shi L. Antimicrobial preservative use in parenteral products: past and present. J Pharm Sci. 2007;96(12):3155–3167. doi: 10.1002/jps.20976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kappelgaard AM, Bojesen A, Skydsgaard K, Sjogren I, Laursen T. Liquid growth hormone: preservatives and buffers. Horm Res. 2004;62(Suppl 3):98–103. doi: 10.1159/000080507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]