Abstract

Introduction

Adnexal or pelvic mass is a finding that commonly raises suspicion for malignancy, especially for ovarian cancer. Proper identification prior to surgery would permit appropriate referral to a specialty center in cases likely to be ovarian cancer, as optimal outcomes in such cases are obtained when surgical staging and treatment are provided at the time of initial surgery.

Methods

We compared the screening capabilities of two in vitro diagnostic multivariate index assays (IVDMIAs), a new IVDMIA (second-generation multivariate index assay: MIA2G) and a currently used triage algorithm (Risk of Ovarian Malignancy Assay: ROMA).

Results

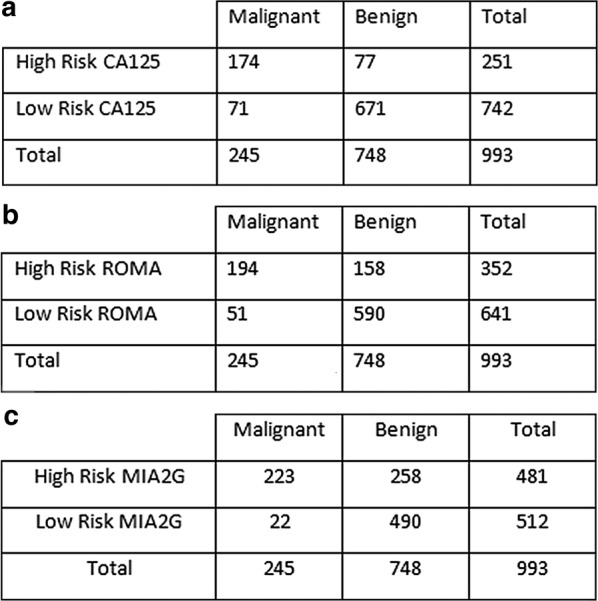

Among 245 subjects (24.7%) determined to have a malignancy, ROMA misclassified 51 malignancies (including 10 high-grade ovarian malignancies), whereas MIA2G misclassified 22 (including 5 high-grade ovarian malignancies). Early stage cancers were more frequently misclassified by ROMA (20 vs. 8 cases). The rate of “test-negative” malignancies was significantly higher for ROMA, while the rate of “test-positive” benign cases was significantly higher for MIA2G.

Conclusion

Triage algorithms play an important role in improving clinical outcomes for women presenting with an adnexal mass regardless of the eventual diagnosis. In this study, MIA2G was shown to correctly predict more cases of ovarian cancer than the ROMA algorithm.

Funding

Aspira Labs/Vermillion Inc.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s12325-019-01010-8) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Adnexal mass, Pelvic mass, Oncology, Ovarian cancer, Triage, Women’s Health

Introduction

The detection of a pelvic adnexal mass increases the risk for pelvic malignancy and thus initiates an evaluation to determine optimal management [1]. An adnexal mass can be the result of a gynecologic or nongynecologic process; however, the approach taken to determine the malignant potential of this finding is related to a complex and multivariate set of demographic and clinical findings including, but not limited to, the age of the patient, the appearance of the mass on imaging, personal and family histories and symptom presentation [1]. The evaluation of a woman with an adnexal mass will invariably lead to a variety of potential interventions, from monitoring without medical or surgical intervention to pharmacologic intervention or surgical extirpation. Of importance is that in cases of adnexal masses associated with pelvic malignancy, optimal outcomes are obtained when the initial surgical procedure is performed by a surgeon skilled and experienced in providing effective surgical management and tumor staging within a facility experienced in caring for such patients [2].

The development of an assay or algorithm that would provide a more accurate and simple approach to malignancy risk assessment in cases of pelvic adnexal masses has been a long-sought-after goal. Such an assay or algorithm would potentially provide information to allow for the appropriate triage so as to improve clinical outcomes without overwhelming certain clinical services, especially those providing surgical oncologic care given the more than 300,000 women who present with an adnexal mass in the USA each year [3, 4]. Several algorithms have been developed that use a variety of serum biomarkers, patient demographics and imaging. The FDA has cleared three IVDMIAs that employ measurements of serum biomarkers for the evaluation of women presenting with a pelvic mass: MIA or Ova1®, a second-generation multivariate index assay (MIA2G, Overa) and the Risk of Ovarian Malignancy Assay (ROMA). These assays provide a relatively simple and straightforward approach to assessing the malignant potential of an adnexal mass. In this article we present the findings of a comparison study of ROMA to the most recently developed second-generation MIA (MIA2G).

Aims/Purpose

The purpose of this study is to compare two FDA-cleared triage algorithms used to assess the malignant potential of an adnexal mass in pre- and postmenopausal women. In addition, these outcomes will also be compared with measurement of CA-125 levels, an approach used by many clinicians to assess the malignant potential of adnexal masses despite the fact that the sole approved indication for the use of CA-125 is for the detection of ovarian cancer recurrence. The use of a triage algorithm in women who present with an adnexal mass can provide invaluable information that can improve clinical outcomes.

Methods

Subjects were enrolled prospectively at 44 sites across the US from primary care women’s health clinics, obstetrics and gynecology groups, gynecologic oncology practices, community and university hospitals, and health maintenance organizations. The subjects were drawn from two previously published trials, OVA1 and OVA500 [5, 6]. Both trials used the same inclusion and exclusion criteria, with inclusion criteria being females 18 years of age and older, documented ovarian tumor with surgery planned within 3 months of imaging, consent to phlebotomy and a signed informed consent. Exclusion criteria were women younger than 18 years of age, a previously diagnosed malignancy in the previous 5 years (with the exception of non-melanoma skin cancer), no planned surgical intervention or lack of consent for a surgical procedure or phlebotomy. For both studies, menopause was defined as lack of menstruation of 12 consecutive months or age 50 or older when menstrual history was not noted. This study was performed in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration of 1964 and its later amendments; institutional review board approval was obtained from each individual site (Table S1).

MIA2G Test

Blood collection and handling methods were described in previously published trials [5, 6]. Serum biomarker concentrations were determined on the Roche Cobas 6000® (Indianapolis, IN, USA) clinical analyzer, utilizing the c501 and e601 modules. Biomarker assays were run according to the manufacturer’s package insert instructions. All measurements were performed at the CLIA/CAP certified laboratory in the Division of Clinical Chemistry, Department of Pathology, Johns Hopkins Medical Institution. The MIA2G multivariate index assay combines the results of the biomarker concentrations from the Cobas assays for apolipoprotein A-1 (APO-A1), cancer antigen 125 (CA 125-II), human epididymis protein 4 (HE4), follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and transferrin (TRF). The MIA2G risk score was calculated using OvaCalc software version 4.0.0, which uses the five biomarker values and a proprietary algorithm to return a dimensionless numerical score from 0.0 to 10.0. A value < 5 is considered low risk, and a value ≥ 5 is considered elevated risk, regardless of menopausal status.

ROMA Calculations

ROMA was calculated from the same Cobas 6000 biomarker values used to calculate the MIA2G result. The calculation used to determine ROMA values was found in Moore et al. 2009 [7]. The biomarkers used to calculate ROMA were the same CA 125 and HE4 values used in the MIA2G algorithm.

Results

Participant data from two previously performed and published prospective clinical trials were combined (OVA1: February 2007–April 2008; OVA500: August 2010–December 2011) to form the overall study cohort. Of the 1110 women enrolled in the two previous trials, 993 subjects were evaluable: 500 from the OVA1 study and 493 from the OVA500 study (Fig. 1). Reasons for excluding study subjects from analysis included: surgery was either not performed or delayed > 3 months, pathology report was not available, blood specimen was unusable, physician assessment was not available, and imaging study did not confirm an adnexal tumor. Table 1 displays the breakdown of subjects used in the study by pathology and menopausal status. The distribution of subjects between menopausal states was approximately equal, being 51% premenopausal and 49% postmenopausal.

Fig. 1.

2 × 2 tables displaying the test performance of each screening tool and the surgical outcomes: a 2 × 2 table for CA125; b 2 × 2 table for ROMA; c 2 × 2 table for MIA2G

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics for evaluable subjects by menopausal status

| All evaluable subjects (N = 993) | Premenopausal subjects (N = 506) | Postmenopausal subjects (N = 487) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | |||

| N | 993 | 506 | 487 |

| Mean (SD) | 50.3 (14.10) | 40.2 (8.67) | 60.8 (10.54) |

| Median | 49 | 42 | 60 |

| Range (min, max) | 18, 92 | 18, 60 | 33, 92 |

| Ethnicity | |||

| Asian | 22 (2.2) | 13 (2.6) | 9 (1.8) |

| Black or African American | 135 (13.6) | 92 (18.2) | 43 (8.8) |

| Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander | 1 (0.1) | 1 (0.2) | 0 (0.0) |

| White | 741 (74.6) | 334 (66.0) | 407 (83.6) |

| Other | 8 (0.8) | 5 (1.0) | 3 (0.6) |

| Hispanic or Latino | 86 (8.7) | 61 (12.1) | 25 (5.1) |

| Pathology diagnosis, n (%) | |||

| Benign ovarian conditions | 748 (75.3) | 433 (85.6) | 315 (64.7) |

| Malignant conditions | 245 (24.7) | 73 (14.4) | 172 (35.3) |

| Epithelial ovarian cancer | 150 (15.1) | 41 (8.1) | 109 (22.4) |

| Other primary ovarian malignancies (not EOC) | 16 (1.6) | 8 (1.6) | 8 (1.6) |

| Low malignant potential (borderline) | 42 (4.2) | 12 (2.4) | 30 (6.2) |

| Non-primary ovarian malignancies with involvement of the ovaries | 23 (2.3) | 8 (1.6) | 15 (3.1) |

| Non-primary ovarian malignancies with no involvement of ovaries | 14 (1.4) | 4 (0.8) | 10 (2.1) |

| Histology (% of EOC and other primary) | |||

| Epithelial: serous | 76 (45.8) | 18 (36.7) | 58 (49.6) |

| Epithelial: mucinous | 17 (10.2) | 5 (10.2) | 12 (10.3) |

| Epithelial: endometroid | 23 (13.9) | 11 (22.4) | 12 (10.3) |

| Epithelial: clear cell | 12 (7.2) | 3 (6.1) | 9 (7.7) |

| Epithelial: transitional | 2 (1.2) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (1.7) |

| Epithelial: carcinosarcoma | 6 (3.6) | 1 (2.0) | 5 (4.3) |

| Epithelial: mixed | 2 (1.2) | 1 (2.0) | 1 (0.9) |

| Epithelial: undifferentiated | 2 (1.2) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (1.7) |

| Epithelial: other | 10 (6.0) | 2 (4.1) | 8 (6.8) |

| Non-epithelial: sex cord stromal | 7 (4.2) | 3 (6.1) | 4 (3.4) |

| Non-epithelial: germ cell | 2 (1.2) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (1.7) |

| Non-epithelial: other | 7 (4.2) | 5 (10.2) | 2 (1.7) |

| Stage (% of EOC and other primary) | |||

| Stage I | 59 (35.5) | 18 (36.7) | 41 (35.0) |

| Stage II | 25 (15.1) | 10 (20.4) | 15 (12.8) |

| Stage III | 72 (43.4) | 18 (36.7) | 54 (46.2) |

| Stage IV | 8 (4.8) | 2 (4.1) | 6 (5.1) |

| Not given | 2 (1.2) | 1 (2.0) | 1 (0.9) |

|

Grade (% of EOC and other primary) Serous grade 3 |

61 (36.7) | 15 (30.6) | 46 (39.3) |

| Other grade 3 | 39 (23.5) | 10 (20.4) | 29 (24.8) |

| Grade 2 | 35 (21.1) | 13 (26.5) | 22 (18.8) |

| Grade 1 | 20 (12.0) | 8 (16.3) | 12 (10.3) |

| Not given | 11 (6.6) | 3 (6.1) | 8 (6.8) |

Menopausal status imputed when not stated time from last menstruation (> 12 months = postmenopausal; < 6 months = premenopausal). If between 6 and 12 months or the time is not given, then premenopausal imputed from when aged ≤ 50; postmenopausal when aged > 50

Of the total population, 245 (24.7%) were diagnosed with a malignancy. The proportion of malignancies among the postmenopausal subgroup was approximately twice the rate for the premenopausal group, which is consistent with menopausal status being a known risk factor for gynecologic cancers. Of the malignancies detected, 166 (67.8% of the malignancies) were primary ovarian malignancies; 42 (17.1%) were (borderline) low malignant potential tumors; 23 (9.4%) were non-primary ovarian malignancies with involvement of the ovaries, and 14 (5.7%) were non-primary ovarian malignancies with no ovarian involvement.

The performance of biomarkers and biomarker panels was assessed in the absence of other physician assessment tools. As shown in Table 2, the evaluation of these subjects’ serum samples by the three assays demonstrated sensitivities of 71.0% (CI 65.0–76.3) for CA125, 79.2% (CI 73.7–83.8) for ROMA, and 91.0% (CI 86.8–94.0) for MIA2G. MIA2G’s sensitivity is statistically significantly higher than that of ROMA, as calculated by McNemar’s chi-square test. Specificities for the three assays were 89.7% (CI 87.3–91.7) for CA125, 78.9% (CI 75.8–81.7) for ROMA and 65.5% (CI 62.0–68.8) for MIA2G. CA125 had the lowest rate of false positives at 7.8% overall. MIA2G showed lower specificity than either ROMA or CA125 with a false-positive rate of 26.0%. Overall, MIA2G had the lowest rate of false negatives, 2.2% overall and 22 out of 245 total malignancies (Table 3). CA125 had a false-negative rate of 7.2% overall, or 71 out of 245 total malignancies. ROMA fell in between with a false-negative rate of 5.1% overall, or 51 out of 245 total malignancies.

Table 2.

Clinical performance of CA125, ROMA and MIA2G—all evaluable subjects

| CA125 (N = 993) | ROMA (N = 993) | MIA2G (N = 993) | Statistical Significance (P value), MIA2G vs. ROMA* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity, | 71.0 | 79.2 | 91.0 | 1.86e−06 |

| n/N | 174/245 | 194/245 | 223/245 | |

| 95% CI | 65.0–76.3 | 73.7–83.8 | 86.8–94.0 | |

| Specificity, % | 89.7 | 78.9 | 65.5 | 3.03e−13 |

| n/N | 671/748 | 590/748 | 490/748 | |

| 95% CI | 87.3–91.7 | 75.8–81.7 | 62.0–68.8 | |

| Positive likelihood ratio | 6.899 | 3.749 | 2.639 | N/A |

| 95% CI | 5.503–8.650 | 3.218–4.367 | 2.373–2.935 | |

| Negative likelihood ratio | 0.323 | 0.264 | 0.137 | N/A |

| 95% CI | 0.265–0.394 | 0.206–0.338 | 0.092–0.205 | |

| Pre-test odds of ovarian malignancy | 0.33–1 | 0.33–1 | 0.33–1 | N/A |

| Post test odds of ovarian malignancy with high risk score | 2.26–1 | 1.23–1 | 0.86–1 | N/A |

| Post test odds of no ovarian malignancy with low risk score | 9.45–1 | 11.57–1 | 22.27–1 | N/A |

CA125 high-risk cutoff: premenopausal subjects > 200 U/ml; postmenopausal subjects > 35 U/ml

ROMA high-risk cutoff: premenopausal subjects ≥ 11.4; postmenopausal subjects ≥ 29.9

*Calculated via McNemar chi-square test

Table 3.

Breakdown of false negatives—all evaluable subjects

| By histology (N = 245) | By stage (N = 166) | By grade (N = 166) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| # Missed | # Missed | # Missed | ||||

| CA125 | EOC | 25 | Stage I | 26 | Serous Gr 3 | 2 |

| Non-EOC | 10 | Stage II | 5 | Other Gr 3 | 5 | |

| LMP | 24 | Stage III | 2 | Grade 2 | 11 | |

| Mets | 5 | Stage IV | 0 | Grade 1 | 11 | |

| Non OvCa | 7 | Not staged | 2 | Not graded | 6 | |

| Total | 71 | Total | 35 | Total | 35 | |

| ROMA | EOC | 16 | Stage I | 19 | Serous Gr 3 | 1 |

| Non-EOC | 7 | Stage II | 1 | Other Gr 3 | 5 | |

| LMP | 21 | Stage III | 2 | Grade 2 | 6 | |

| Mets | 3 | Stage IV | 0 | Grade 1 | 6 | |

| Non OvCa | 4 | Not staged | 1 | Not graded | 5 | |

| Total | 51 | Total | 23 | Total | 23 | |

| MIA2G | EOC | 5 | Stage I | 8 | Serous Gr 3 | 0 |

| Non-EOC | 4 | Stage II | 0 | Other Gr 3 | 1 | |

| LMP | 10 | Stage III | 0 | Grade 2 | 3 | |

| Mets | 1 | Stage IV | 0 | Grade 1 | 2 | |

| Non OvCa | 2 | Not staged | 1 | Not graded | 3 | |

| Total | 22 | Total | 9 | Total | 9 | |

CA125 high-risk cutoff: premenopausal subjects > 200 U/ml; postmenopausal subjects > 35 U/ml

ROMA high-risk cutoff: premenopausal subjects ≥ 11.4; postmenopausal subjects ≥ 29.9

The clinical performance of the assays stratified by the subjects’ menopausal status is presented in Table 4. CA 125 performance was based on defined menopausal status-dependent cutoff values [5]. Premenopausal sensitivity for CA125 was 50.7%. ROMA and MIA2G also showed somewhat higher sensitivity for postmenopausal subjects, but the difference was not as great as that for CA125. Regarding specificity, both MIA2G and CA125 demonstrated higher values among premenopausal subjects, whereas ROMA was somewhat higher for postmenopausal. Overall, the lowest false-positive rate was that for premenopausal CA125 at 3.6%, and the lowest false-negative rate was premenopausal MIA2G at 1.4%. As with the overall sensitivities and specificities, ROMA generally fell somewhere between the two.

Table 4.

Clinical performance of CA125, ROMA and MIA2G—all evaluable subjects by menopausal status

| CA125 | ROMA | MIA2G | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre | Post | Pre | Post | Pre | Post | |

| (N = 506) | (N = 487) | (N = 506) | (N = 487) | (N = 506) | (N = 487) | |

| Sensitivity, % | 50.7 | 79.7 | 78.1 | 79.7 | 90.4 | 91.3 |

| n/N | 37/73 | 137/172 | 57/73 | 137/172 | 66/73 | 157/172 |

| 95% CI | 39.5–61.8 | 73.0–85.0 | 67.3–86.0 | 73.0–85.0 | 81.5–95.3 | 86.1–94.6 |

| Specificity, % | 95.8 | 81.3 | 76.2 | 82.5 | 70 | 59.4 |

| n/N | 415/433 | 256/315 | 330/433 | 260/315 | 303/433 | 187/315 |

| 95% CI | 93.5–97.4 | 76.6–85.2 | 72.0–80.0 | 78.0–86.3 | 65.5–74.1 | 53.9–64.6 |

| Positive likelihood ratio | 12.193 | 4.253 | 3.282 | 4.562 | 3.011 | 2.246 |

| 95% CI | 7.353–20.217 | 3.338–5.418 | 2.666–4.041 | 3.547–5.868 | 2.561–3.541 | 1.950–2.587 |

| Negative likelihood ratio | 0.515 | 0.25 | 0.288 | 0.247 | 0.137 | 0.147 |

| 95% CI | 0.407–0.650 | 0.185–0.338 | 0.186–0.445 | 0.183–0.333 | 0.068–0.278 | 0.090–0.240 |

| Pre-test odds of ovarian malignancy | 0.17–1 | 0.55–1 | 0.17–1 | 0.55–1 | 0.17–1 | 0.55–1 |

| Post-test odds of ovarian malignancy with high risk score | 2.06–1 | 2.32–1 | 0.55–1 | 2.49–1 | 0.51–1 | 1.23–1 |

| Post test odds of no ovarian malignancy with low risk score | 11.53–1 | 7.31–1 | 20.63–1 | 7.43–1 | 43.29–1 | 12.47–1 |

| Positive test rate (as overall %) | 10.9 | 40.2 | 31.6 | 39.4 | 38.7 | 58.5 |

| False positive rate (as overall %) | 3.6 | 12.1 | 20.4 | 11.3 | 25.7 | 26.3 |

| False negative rate (as overall %) | 7.1 | 7.2 | 3.2 | 7.2 | 1.4 | 3.1 |

CA125 high-risk cutoff: premenopausal subjects > 200 U/ml, postmenopausal subjects > 35 U/ml; ROMA high-risk cutoff: premenopausal subjects ≥ 11.4, postmenopausal subjects ≥ 29.9

Table 5 shows the sensitivities of the three assays characterized by tumor histology. As seen in the overall clinical performance, CA125 had the lowest sensitivity, MIA2G had the highest, and ROMA fell in between. This was true for all the histologic subtypes of malignancies detected in this study: primary ovarian (epithelial and non-epithelial), low malignant potential (LMP), metastatic with ovarian involvement and non-ovarian. All three assays had the highest sensitivity for primary epithelial ovarian malignancies: 83.3% (CI 76.6–88.4) for CA125, 89.3% (CI 83.4–93.3) for ROMA and 96.7% (CI 92.4–98.6) for MIA2G. The lowest histologic subgroup sensitivities were primary non-epithelial ovarian malignancies for CA125, which was 37.5% (CI 18.5–61.4), and for MIA2G at 75.0% (CI 50.5–89.8). ROMA’s lowest was for LMP masses, with a sensitivity of 50.0% (CI 35.5–64.5).

Table 5.

Sensitivity of multivariate risk stratification from CA125, ROMA and MIA2G by primary histology—all evaluable subjects

| CA125 | ROMA | MIA2G | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Epithelial, % | 83.3 | 89.3 | 96.7 |

| n/N | 125/150 | 134/150 | 145/150 |

| 95% CI | 76.6–88.4 | 83.4–93.3 | 92.4–98.6 |

| Non-epithelial, % | 37.5 | 56.3 | 75.0 |

| n/N | 6/16 | 9/16 | 12/16 |

| 95% CI | 18.5–61.4 | 33.2–76.9 | 50.5–89.8 |

| LMP, % | 42.9 | 50.0 | 76.2 |

| n/N | 18/42 | 21/42 | 32/42 |

| 95% CI | 29.1–57.8 | 35.5–64.5 | 61.5–86.5 |

| Metastatic, % | 78.3 | 87.0 | 95.7 |

| n/N | 18/23 | 20/23 | 22/23 |

| 95% CI | 58.1–90.3 | 67.9–95.5 | 79.0–99.2 |

| Non-ovarian, % | 50.0 | 71.4 | 85.7 |

| n/N | 7/14 | 10/14 | 12/14 |

| 95% CI | 26.8–73.2 | 45.4–88.3 | 60.1–96.0 |

CA125 high-risk cutoff: premenopausal subjects > 200 U/ml, postmenopausal subjects > 35 U/ml; ROMA high-risk cutoff: premenopausal subjects ≥ 11.4, postmenopausal subjects ≥ 29.9

The sensitivities are also characterized by stage and grade of the primary ovarian malignancy in Table 6. One considerable challenge related to the relative dearth of successful outcomes in ovarian cancer is the relatively high frequency of advanced stage disease at the time of detection, resulting in higher rates of adverse outcomes compared with tumors detected at a less advanced stage [7]. However, in this study a higher rate of early detection was evident, possibly leading to longer life expectancy that may be further facilitated by recent findings showing correlation between specific deleterious somatic genomic variants and improved outcomes with certain chemotherapeutic regimens [8]. The combined early stage (I and II) sensitivities were 63.1% (CI 52.4–72.6) for CA125, 76.2% (CI 66.1–84.0) for ROMA and 90.5% (CI 82.3–95.1) for MIA2G, as opposed to the sensitivities for late stage cancers, which were 97.5% (CI 91.3–99.3) for CA125 and ROMA and 100% (CI 95.4–100.0) for MIA2G. MIA2G is also notable for correctly identifying all stage III cancers, which both ROMA and CA125 were unable to accomplish. A similar phenomenon could be seen for cancer grade, with grade 3 malignancies having the highest sensitivities across all three assays for those that were graded followed by grade 2, with grade 1 having the lowest sensitivities. For all stages and grades, the generally observed trend of MIA2G having the highest sensitivity, followed by ROMA and then CA125, is also present. It is also noteworthy that MIA2G had a 100% sensitivity for both late stage and grade 3 (serous) primary ovarian malignancies.

Table 6.

Sensitivity of multivariate risk stratification from CA125, ROMA and MIA2G by stage and grade of primary ovarian malignancy—all evaluable subjects

| CA125 | ROMA | MIA2G | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stage I, % | 55.9 | 67.8 | 86.4 |

| n/N | 33/59 | 40/59 | 51/59 |

| 95% CI | 43.3–67.8 | 55.1–78.3 | 75.5–93.0 |

| Stage II, % | 80.0 | 96.0 | 100.0 |

| n/N | 20/25 | 24/25 | 25/25 |

| 95% CI | 60.9–91.1 | 80.5–99.3 | 86.7–100.0 |

| Stage III, % | 97.2 | 97.2 | 100.0 |

| n/N | 70/72 | 70/72 | 72/72 |

| 95% CI | 90.4–99.2 | 90.4–99.2 | 94.9–100.0 |

| Stage IV, % | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| n/N | 8/8 | 8/8 | 8/8 |

| 95% CI | 67.6–100.0 | 67.6–100.0 | 67.6–100.0 |

| Not staged, % | 0.0 | 50.0 | 50.0 |

| n/N | 0/2 | 1/2 | 1/2 |

| 95% CI | 0.0–65.8 | 9.5–90.5 | 9.5–90.5 |

| Early stage (I and II), % | 63.1 | 76.2 | 90.5 |

| n/N | 53/84 | 64/84 | 76/84 |

| 95% CI | 52.4–72.6 | 66.1–84.0 | 82.3–95.1 |

| Late stage (III and IV), % | 97.5 | 97.5 | 100.0 |

| n/N | 78/80 | 78/80 | 80/80 |

| 95% CI | 91.3–99.3 | 91.3–99.3 | 95.4–100.0 |

| All primary, % | 78.9 | 86.1 | 94.6 |

| n/N | 131/166 | 143/166 | 157/166 |

| 95% CI | 72.1–84.4 | 80.1–90.6 | 90.0–97.1 |

| Grade 3 serous, % | 96.7 | 98.4 | 100.0 |

| n/N | 59/61 | 60/61 | 61/61 |

| 95% CI | 88.8–99.1 | 91.3–99.7 | 94.1–100.0 |

| Other grade 3, % | 87.2 | 87.2 | 97.4 |

| n/N | 34/39 | 34/39 | 38/39 |

| 95% CI | 73.3–94.4 | 73.3–94.4 | 86.8–99.5 |

| Grade 2, % | 68.6 | 82.9 | 91.4 |

| n/N | 24/35 | 29/35 | 32/35 |

| 95% CI | 52.0–81.4 | 67.3–91.9 | 77.6–97.0 |

| Grade 1, % | 45.0 | 70.0 | 90.0 |

| n/N | 9/20 | 14/20 | 18/20 |

| 95% CI | 25.8–65.8 | 48.1–85.5 | 69.9–97.2 |

| Not graded, % | 45.5 | 54.5 | 72.7 |

| n/N | 5/11 | 6/11 | 8/11 |

| 95% CI | 21.3–72.0 | 28.0–78.7 | 43.4–90.3 |

CA125 high-risk cutoff: premenopausal subjects > 200 U/ml; postmenopausal subjects > 35 U/ml

ROMA high-risk cutoff: premenopausal subjects ≥ 11.4; postmenopausal subjects ≥ 29.9

Discussion

The detection of an adnexal mass, regardless of the manner in which it was detected, should prompt an evaluation to determine the need for intervention versus the ability to monitor without intervention [1]. This decision is one fraught with complexity, ranging from the presence of symptoms at the time of detection to the age of the patient, including her family and personal histories as well as the appearance of the mass with imaging modalities [1]. As such, there is no single or simple approach to determine the most appropriate management of the adnexal mass. Given the increased risk for malignancy in these types of cases, this assessment should take into account all factors that best serve to characterize the benign or malignant potentials of the clinical finding. Urban and colleagues [9] recently showed that combining an assessment of symptoms with MIA2G to evaluate women presenting with an adnexal mass further improved the accuracy of the triage assessment for ovarian cancer.

It is obvious that the detection of an adnexal mass requires an accurate assessment of its malignant potential to best provide ongoing care. This assessment is even more critical given that most women found to have an adnexal mass do not have immediate access to a gynecologic oncologist or surgical oncologist who practices within a hospital-based system experienced in caring for women and men with cancer. The inability to accurately assess the malignant potential of an adnexal mass thus creates a profound clinical dilemma: either refer all women with an adnexal mass to a center with trained cancer professionals and overwhelm that system with many women who have benign adnexal lesions or surgically evaluate many if not most such women and then refer only those women with pathology-proven malignancies for care by a cancer center. Indeed, an often-practiced approach by some non-oncologic surgeons and gynecologists has been to perform a surgical procedure to obtain a tissue sample solely for malignancy confirmation. Once cancer is confirmed by pathology, the patient is then sent to a cancer center for further treatment and care. However, this practice serves to reduce the longevity and quality of life for that woman, given the fact that optimal clinical outcomes are achieved when women are cared for by skilled cancer physicians in experienced cancer care facilities at the time of their initial procedures [2]. Regardless of the economic impact of referring a surgical patient elsewhere, it behooves every clinician to make every attempt to gain as much insight as possible into the adnexal mass prior to intervention so as to optimize clinical outcome. In cases of adnexal mass, the ready availability of triage algorithms such as ROMA and M1A2G could considerably reduce the frequency of needless and harmful surgical procedures for malignancy confirmation that adversely impact the patient and her prognosis.

In this study, we found that all triage approaches provided invaluable information that could serve to provide the best care to women with an adnexal mass. For those at a low risk for malignancy, surgery close to home by a skilled gynecologic surgeon would provide good care without the need to travel long distances. In this comparative study, an assessment of the overall clinical performance showed CA125 to have the lowest sensitivity and MIA2G to have the highest. This was true for all histologic subtypes of malignancies detected in this study: primary ovarian (epithelial and non-epithelial), low malignant potential (LMP), metastatic with ovarian involvement and non-ovarian. Conversely, MIA2G showed lower specificity than either ROMA or CA125, though MIA2G had the lowest rate of false negatives.

Despite our findings, as well as those of other studies that characterize CA125 to be considerably less sensitive and specific than multimodal risk algorithms such as MIA2G or even ultrasound [10] for determining the likelihood of malignancy, the use of CA125 alone to assess women with adnexal findings remains a popular choice in the assessment of women presenting with an adnexal mass. A recent study from Italy by Piovano and colleagues [11] found that adding CA125 and ROMA to triage algorithms for postmenopausal women with adnexal masses improved screening accuracy compared with ultrasound alone; the addition of ROMA was considerably more expensive and provided for minimal additional screening benefit compared with CA125 alone. While economic considerations do play some role in the continued use of CA125 alone for the presurgical assessment of women with adnexal masses, the availability of FDA-cleared multimodal assays and the lack of FDA clearance for the use of CA125 in these clinical situations continue to call into question the ongoing use of a single analyte assay for which there is considerable evidence to support it being an inferior triage process for women presenting with adnexal masses compared with multimodal algorithms [12]. In addition, it begs repeating that the use of any multimodal assay in such cases should not be used for the initial evaluation of an adnexal mass or for the determination of clinical management in such cases. Rather, an IVDMIA should be used solely to determine optimal personnel and venue should surgical intervention be chosen to manage the adnexal mass.

Our study is impacted by several limitations. First, while this study was a prospective enrollment study, a considerable number of participants did not complete the study requirements for the reasons listed above. It is unclear whether the exclusion of these enrollees had an impact on the outcomes of our study. Another limitation was the lack of a consistent definition of adnexal mass used throughout the study centers. This was done to create a more “real-world” study, but may have led to the inclusion of inappropriate subjects or the exclusion of appropriate subjects.

Conclusion

Our study shows that while all algorithmic approaches to adnexal mass triage provide valuable information concerning malignant potential, each algorithm has unique triage characteristics that will appeal to particular clinicians. M1A2G is characterized by the highest sensitivity and lowest false-negative rate in this comparison study, thus making it the test most likely to correctly characterize an adnexal malignancy with the lowest likelihood of a missed malignancy. However, this assay will also characterize more women with benign findings as having an increased risk of malignancy than the other two assays studied. Regardless of the triage algorithm used by an individual clinician, the use of a triage algorithm will invariably help guide clinicians in their decision to best manage a woman presenting with an adnexal mass, thus increasing the likelihood that the care provided to that woman will be appropriate and, in cases of pelvic cancer, maximize the survival rate by optimizing that woman’s initial surgical intervention and care.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge and thank Alan Smith, MS, Vinicius Bonato, PhD, Donald Munroe, PhD, Judith Wolf, MD, and Valerie Palmieri for their work on and support of this project. Most importantly, we thank the participants of the study, whose participation ensured that this study could be undertaken and completed and will hopefully lead to improved clinical outcomes for women presenting with adnexal masses.

Funding

The trials performed that provided the data for this study were funded by Aspira Labs/Vermillion Inc. The study sponsor (Vermillion/Aspira Labs) is also funding all of the processing fees and any Open Access charges. All authors had full access to all of the data in this study and take complete responsibility for the integrity of the data and accuracy of the data analysis.

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Prior Presentation

Presented at the Annual Clinical Meeting of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, 2016.

Disclosures

Lee P. Shulman is a consultant for Aspira/Vermillion and is a member of journal’s Editorial Board. He received no compensation for authorship and will not receive any compensation if the manuscript is accepted for publication. Marra Francis was previously employed by Aspira/Vermillion. Marra Francis did not receive compensation for authorship and will not receive any compensation if the manuscript is accepted for publication. Todd Papas was previously employed by Aspira/Vermillion. Todd Papas did not receive compensation for authorship and will not receive any compensation if the manuscript is accepted for publication. Rowan Bullock is employed by Aspira/Vermillion. He received no compensation for authorship and will not receive any compensation if the manuscript is accepted for publication.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This study was performed in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration of 1964 and its later amendments. Institutional review board approval was obtained from each individual site participating in the study (Table S1).

Data Availability

The data sets generated and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Footnotes

Enhanced Digital Features

To view enhanced digital features for this article go to 10.6084/m9.figshare.8229830.

References

- 1.ACOG Practice Bulletin. Evaluation and management of adnexal masses. No. 174, November 2016.

- 2.Paulsen T, Kaern J, Kjaerheim J, et al. Improved short-term survival for advanced ovarian, tubal, and peritoneal cancer patients operated at teaching hospitals. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2006;16(Suppl 1):11–17. doi: 10.1136/ijgc-00009577-200602001-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Curtin JP. Management of the adnexal mass. Gynecol Oncol. 1994;55(3 Pt 2):S42-6. doi: 10.1006/gyno.1994.1340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Conference Statement Ovarian cancer: screening, treatment, and follow-up. Gynecol Oncol. 1994;55(3 Pt 2):S4. doi: 10.1006/gyno.1994.1333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ueland FR, Desimone CP, Seamon LG, et al. Effectiveness of a multivariate index assay in the preoperative assessment of ovarian tumors. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117:1289–1297. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31821b5118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Coleman RL, Herzog TJ, Chan DW, et al. Validation of a second-generation multivariate index assay for malignancy risk of adnexal masses. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;215(1):82.e1–82.e11. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2016.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moore RG, McMeekin DS, Brown AK, et al. A novel multiple marker bioassay utilizing HE4 and CA125 for the prediction of ovarian cancer in patients with a pelvic mass. Gynecol Oncol. 2008;112(1):40–46. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2008.08.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hawke J, Hahnen E, Schneider S, et al. Deleterious somatic variants in 473 consecutive individuals with ovarian cancer: results of the observational AGO-TR1 study ( NCT02222883) J Med Genet. 2019 doi: 10.1136/jmedgenet-2018-105930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Urban RR, Pappas TC, Bullock RG, et al. Combined symptom index and second-generation multivariate biomarker test for prediction of ovarian cancer in patients with an adnexal mass. Gynecol Oncol. 2018;150(2):318–323. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2018.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Van Calster B, Timmerman D, Bourne T, et al. Discrimination between benign and malignant adnexal masses by specialist ultrasound examination versus serum CA-125. JNCI. 2007;99(22):1706–1714. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djm199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Piovano E, Cavallero C, Fuso L, et al. Diagnostic accuracy and cost-effectiveness of different strategies to triage women with adnexal masses: a prospective study. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2017;50(3):395–403. doi: 10.1002/uog.17320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sundar S, Rick C, Dowling F, et al. Refining Ovarian Cancer Test accuracy Scores (ROCkeTS): protocol for a prospective longitudinal test accuracy study to validate new risk scores in women with symptoms of suspected ovarian cancer. BMJ Open. 2016;6(8):e010333. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data sets generated and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.