Abstract

Introduction

A systematic literature review was conducted to review and summarize the economic impact of non-medical switching (NMS) from biologic originators to their biosimilars (i.e., switching a patient’s medication for reasons irrelevant to the patient’s health).

Methods

English publications reporting healthcare resource utilization (HRU) or costs associated with biosimilar NMS were searched in PubMed and EMBASE over the past 10 years and from selected scientific conferences over the past 3 years, along with gray literature for all biologics with an approved biosimilar (e.g., tumor-necrosis factor inhibitors, erythropoiesis-stimulating agents, insulin and hormone therapies).

Results

A total of 1311 publications were retrieved, where 54 studies met the selection criteria. Seventeen studies reported increased real-world HRU or costs related to biosimilar NMS, e.g., higher rates of surgery (11%), steroid use (13%) and biosimilar dose escalating (6–35.4%). Among the studies that the estimated cost impact associated with NMS, 33 reported drug costs reduction, 12 reported healthcare costs post-NMS without a detailed breakdown, and 5 reported NMS setup and managing costs. Cost estimation/simulation studies demonstrated the cost reduction associated with NMS. However, variation across studies was substantial because of heterogeneity in study designs and assumptions (e.g., disease areas, scenarios of drug price discount rates, cost components, population size, study period, etc.).

Conclusion

Real-world studies reporting the economic impact of biosimilar NMS separately from drug costs are emerging, and those that reported such results found increased HRU in patients with biosimilar NMS. Studies of cost estimation have been largely limited to drug prices. Comprehensive evaluation of the economic impact of NMS should incorporate all important elements of healthcare service needs such as drug price, biologic rebates, HRU, NMS program setup, administration and monitoring costs.

Funding

AbbVie.

Electronic Supplementary Material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s12325-019-00998-3) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Biologics, Biosimilar, Drug costs, Non-medical switching, Pharmacology, Systematic literature review

Introduction

Biologics are large complex molecules, or mixtures of molecules, that have revolutionized the treatment of many chronic diseases, including diabetes, hemophilia, hepatitis, cystic fibrosis, growth deficiency, several types of cancer and autoimmune diseases such as rheumatoid and psoriatic arthritis, psoriasis and inflammatory bowel disease [1, 2]. In recent years, a number of biologics have reached the end of their market exclusivity; many biosimilars, biopharmaceutical drugs designed to have active properties similar to their reference biologics, have been developed or are under development [3]. Unlike generic versions of synthetic small-molecule drugs, biosimilars are not exact copies but only highly similar to the approved reference biologics (i.e., originator biologics) [3, 4]. This is due to the intrinsic manufacturing variability of biologics, which inevitably, for large biologic molecules, leads to a degree of structural differences between originator and biosimilar products [3, 4]. However, within an acceptable range of variations that have been clearly defined by regulatory agencies in the USA, Europe and other countries, a biosimilar is required to be highly similar to an originator biologic without functional consequences in terms of efficacy, safety, potency, pharmacokinetic parameters and immunogenicity [3, 4].

Biosimilars may be priced lower than the originator biologics because the research and development processes are typically shorter and less labor-intensive with more relaxed regulatory requirements [4]. In Europe, since the first biosimilar was approved in 2006 there have been over 40 biosimilars on the market [5]; depending on the type, biosimilars have been priced 25–70% less than their originators [4, 6]. In the US, discounts for biosimilars are generally smaller than the discounts for biosimilars in Europe [4, 7]. For instance, the first two biosimilars approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), filgrastim and infliximab, had a list price of only 15% lower than their originator biologics [3, 7]. Since then, other biosimilars have been launched to the US market at similar discounted rates, with the highest discount to date being 35% for an infliximab biosimilar [7, 8].

Non-medical switch (NMS) refers to switching a patient’s medication for reasons other than a patient’s health and safety. In the past, NMS of small-molecule drugs from branded to their generic versions resulted in significant cost savings for both patients and payers due to the lower drug prices of generic medications [9–11]. However, the economic impact of an originator-to-biosimilar NMS is more complex given that the two drugs are not always identical, and a comparison based only on drug costs would not provide a full picture of the economic implications of NMS [4, 11, 12]. For instance, studies have identified costs associated with biosimilar NMS including costs of training physicians and nurses, pre-NMS planning (e.g., laboratory tests), post-NMS monitoring (e.g., laboratory tests or medical visits following dose adjustments or side effects) and NMS-related administrative procedures (e.g., prior authorization or new reimbursement procedures) [12, 13]. Specifically in the US, a combination of rebates and discounts that biologics manufacturers offer to payers and pharmacy benefits managers may result in comparable purchase prices for originators and biosimilars, effectively reducing or even eliminating the cost advantage of biosimilar NMS [4, 7, 12].

In light of the increasing number of biosimilars on the market and in development worldwide, consideration of the cost implication of biosimilar NMS is important [14]. We conducted a systematic review of the literature to assess and summarize the healthcare resource utilization (HRU) and costs reported for patients undergoing biosimilar NMS.

Methods

Literature Search

A systematic literature review was conducted in September 2018 to identify published studies reporting data on the HRU and/or costs associated with biologic-to-biosimilar NMS. The literature review was designed, performed and reported following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guidelines [15]. Full-text articles published in English between January 2008 and September 2018 were searched using the PubMed and EMBASE databases. In addition, to capture results from recent studies that might not have been published as full-text articles at the time of the search, key conference proceedings of disease areas that may be treated with biologics/biosimilars from 2014 to 2018, depending on availability, were searched using the websites of the following conferences:

American College of Rheumatology Annual Meeting (ACR/ARHP)

American College of Gastroenterology Annual Scientific Meeting (ACG)

American Diabetes Association Scientific Sessions (ADA)

American Society of Hematology Annual Meeting (ASH)

American Thoracic Society International Conferences (ATS)

Annual Meeting of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD)

American Society of Clinical Oncology Annual Meeting (ASCO)

European League Against Rheumatism Annual Congress (EULAR)

European Congress of Endocrinology (ECE)

European Society of Cardiology Annual Congress (ESC)

European Crohn’s and Colitis Organization Annual Congress (ECCO gastro)

International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research Annual European Congress (ISPOR Europe)

International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research Annual International Meeting (ISPOR International)

Scientific Sessions of American Heart Association (AHA)

European Cancer Congress (ECCO cancer).

Search terms included “biosimilar”, “biosimilar agent”, the names of individual biosimilars (e.g., “etanercept”, “epoetin alfa biosimilar”, “filgrastim biosimilar”, etc.), “HRU”, “health resources”, “resource utilization”, “cost”, “health care costs”, “non-medical reasons”, “switch” and other various terms related to HRU, costs and NMS (Electronic Supplementary Table S1). Boolean operators and MeSH terms were used in PubMed and EMBASE databases. For conference proceedings, where search engines were not as rigorous as PubMed and EMBASE and no Boolean operators were available, simple search terms (e.g., biosimilar, non-medical switching, NMS, switching) were used. Finally, a search of the gray literature was conducted using Google Scholar to identify any relevant studies not captured by the database or conference proceeding search.

Literature Screening

Inclusion and exclusion criteria were defined a priori (Table 1). Based on these criteria, the articles identified during the PubMed/EMBASE search were screened in two levels: in level one, all articles were screened based on their title and abstract and, in level two, those meeting the inclusion criteria were screened based on their full text using the same criteria as in level one. In level one, when decisions to include or exclude a publication could not be made based solely on its title and abstract, the full text was obtained and screened as part of level two. The title and abstracts of conference proceedings were screened in level one; no level two screening was performed as the full text was not available.

Table 1.

Characteristics and design of the identified studies

| Disease areas | Citations | Publication type | Study type | Biosimilar | Total population | Time horizon |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rheumatology, dermatology and gastroenterology diseases | Jha 2015 [46] | Abstract | Simulation study | Biosimilar infliximab | NR | 1 year |

| Jha 2015 [47] | Journal article | Simulation study | Biosimilar infliximab | 3,750,611 | 1 year | |

| Ala 2016 [48] | Abstract | Center-based cohort study | Biosimilar infliximab | 21 | 6 months | |

| Becciolini 2016 [49] | Abstract | Simulation study | Biosimilar etanercept | NR | 3 years | |

| Bhattacharyya 2016 [50] | Abstract | Simulation study | Biosimilar etanercept | 27,052 | 1 year | |

| Bocquet 2016 [51] | Abstract | Simulation study | Biosimilar infliximab | 5483 | 1 year | |

| Rahmany 2016 [52] | Abstract | Center-based cohort study | Biosimilar infliximab | 88 | 6 months | |

| Shah 2016 [53] | Abstract | Simulation study | Biosimilar infliximab | 7343 | 1 year | |

| Biosimilar adalimumab | ||||||

| Sheppard 2016 [34] | Abstract | Center-based cohort study | Biosimilar infliximab | 25 | 1 year | |

| Trancart 2016 [54] | Abstract | Simulation study | Biosimilar etanercept | 45,903 | 3 years | |

| Alexandre 2017 [55] | Abstract | Simulation study | Biosimilar infliximab | 3142 | 5 years | |

| Barnes 2017 [38] | Abstract | Simulation study | Biosimilar etanercept | NR | NR | |

| Dyball 2017 [36] | Abstract | Center-based cohort study | Biosimilar etanercept | 38 | NR | |

| Glintborg 2017 [16] | Abstract | Registry/National database | Biosimilar infliximab | 769 | 1 year | |

| Gomez 2017 [56] | Abstract | Simulation study | Biosimilar adalimumab | 326 | 1 year | |

| Gutermann 2017 [33] | Abstract | Center-based cohort study | Biosimilar infliximab | 333 | 10 months | |

| Plevris 2017 [29] | Abstract | Center-based cohort study | Biosimilar infliximab | 161 | NR | |

| Ratnakumaran 2017 [32] | Journal article | Center-based cohort study | Biosimilar infliximab | 210 | 1 year | |

| Razanskaite 2017 [35] | Journal article | Center-based cohort study | Biosimilar infliximab | 143 | 1 year | |

| Rodriguez 2017 [28] | Abstract | Center-based cohort study | Biosimilar infliximab | 72 | 1 year | |

| St. Clair Jones 2017 [31] | Abstract | Center-based cohort study | Biosimilar infliximab | 71 | 6 months | |

| Szlumper 2017 [57] | Abstract | Center-based cohort study | Biosimilar etanercept | 39 | 3 months | |

| Szlumper 2017 [19] | Abstract | Center-based cohort study | Biosimilar etanercept | 109 | 7 months | |

| Barnes 2018 [23] | Abstract | Interview | Biosimilar etanercept | 627–689 | NR | |

| Garcia-Fernandez 2018 [58] | Abstract | Center-based cohort study | Biosimilar infliximab | 76 | 8 months | |

| Gibofsky 2018 [39] | Abstract | Simulation study | NR | 5000 | < 1 year | |

| Gibofsky 2018 [41] | Journal article | Simulation study | NR | 1000 | 3 months | |

| Glintborg 2018 [17] | Journal article | Registry/National database | Biosimilar infliximab | 769 | 1 year | |

| Healy 2018 [59] | Abstract | Center-based cohort study | Biosimilar infliximab | 60 | 1 year | |

| Husereau 2018 [42] | Journal article | Simulation study | Biosimilar infliximab | NR | NR | |

| Ma 2018 [60] | Abstract | Center-based cohort study | Biosimilar etanercept | 50 | 6 months | |

| Mora 2018 [61] | Abstract | Center-based cohort study | Biosimilar infliximab | 18 | 1 year | |

| Nisar 2018 [27] | Abstract | Center-based cohort study | Biosimilar rituximab | 39 | 1 year | |

| O’Brien 2018 [62] | Abstract | Center-based cohort study | Biosimilar infliximab | 20 | 8 months | |

| Peral 2018 [20] | Abstract | Simulation study | Biosimilar etanercept | NR | 1 year | |

| Rodriguez 2018 [26] | Abstract | Center-based cohort study | Biosimilar infliximab | 48 | 11 months | |

| Shah 2018 [21] | Abstract | Center-based cohort study | Biosimilar etanercept | 151 | 1 year | |

| Shah 2018 [63] | Abstract | Center-based cohort study | Biosimilar etanercept | 151 | 6 months | |

| Valido 2018 [37] | Abstract | Center-based cohort study | Biosimilar infliximab | 60 | 1 year | |

| Zahorian 2018 [22] | Abstract | Center-based cohort study | Biosimilar infliximab | 110 | NR | |

| NHL, multiple myeloma, colorectal and breast cancer | Abraham 2014 [64] | Journal article | Simulation study | Biosimilar epoetin alfa | 100,000 | 15 weeks |

| Sun 2015 [65] | Journal article | Simulation study | Biosimilar filgrastim | 10,000 | 14 days | |

| McBride 2017 [66] | Abstract | Simulation study | Biosimilar filgrastim | 20,000 | Chemotherapy of 1 or 6 cycles | |

| McBride 2017 [67] | Abstract | Simulation study | Biosimilar filgrastim-sndz | 20,000 | 5, 7, 11, 14 days | |

| McBride 2017 [68] | Journal article | Simulation study | Biosimilar filgrastim-sndz | 20,000 | 1–14 days | |

| Peck 2017 [25] | Abstract | Center-based cohort study | Biosimilar filgrastim | 100 | 1 year | |

| Hemodialysis | Minutolo 2016 [30] | Journal article | Center-based cohort study | Biosimilar epoetin alfa | 149 | 36 weeks |

| Biosimilar epoetin zeta | ||||||

| Pediatric growth disturbances | Flodmark 2013 [24] | Journal article | Center-based cohort study | Biosimilar somatropin | 98 | About 3 years |

| Obstetrics/gynecology | Ravonimbola 2017 [69] | Abstract | Simulation study | Biosimilar follitropin alfa | 100 | NR |

| Not reported | Brown 2016 [40] | Abstract | Simulation study | NR | 1 year | |

| Claus 2016 [70] | Abstract | Simulation study | Biosimilars of infliximab, epoeitin alfa, filgrastim and follitropin alfa | NR | 5 years | |

| Hakim 2017 [43] | Journal article | Policy review | NA | 1000 | NA | |

| Phillips 2017 [18] | Abstract | Registry/National database | Biosimilar infliximab | 1524 | 1 year | |

| Reichardt 2017 [71] | Abstract | Simulation study | Biosimilar infliximab | NR | NR |

NHL non-Hodgkin lymphoma, NA not applicable, NR not reported

To ensure accuracy, the screening of both publications and conference proceedings was conducted by two reviewers independently. In case of disagreement between the two reviewers, a third reviewer was consulted to reach a consensus.

Data Extraction and Analysis

After screening, data extraction was performed by one reviewer and subsequently audited by a second reviewer to ensure accuracy. The data extracted from the identified publications and conference proceeding, whenever available, were the following: publication year, name of conference (for conference proceedings), country, drug information (originator and biosimilar brand name), study design (study type, data source, number of cohorts or treatment groups, study period and outcomes), study population (disease area, sample size, prior treatment experience with originator, switch rate, biosimilar discontinuation rate and biosimilar-to-biologic switch-back rate), cost and/or HRU input (data source, cost and/or HRU component considered, assumptions, cost year, currency and cost unit) and cost and/or HRU outcomes (HRU and/or cost differences between biosimilars and originators). The extracted data pertaining to study characteristics and design are summarized in Table 1, post-NMS HRU in Table 2 and post-NMS drug costs in Table 3. When extracting drug costs, due to large variations in study design, study population, biosimilar-to-biologic switch-back rate and study duration, total drug costs were calculated per switched population. Annual drug costs and annual total healthcare costs were summarized based on studies directly reporting annual costs. All costs were converted and inflated to 2018 euro (€). Due to the substantial variation in study designs and outcomes, no meta-analysis was conducted. Extracted data were descriptively summarized to retain most of the information identified from the identified studies.

Table 2.

Post-NMS HRU and HRU-related costs

| Citations | Diseases | Study type | Biosimilar | Time horizon | Data source | Reported HRU |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flodmark 2013 [24] | Pediatric growth disturbances | Center-based cohort study | Biosimilar somatropin | About 3 years | Hospital data | Twelve patients experienced injection-site pain, three required an extra visit to the responsible physician or specialized nurse, 10 required extra phone contact with the physician/nurse |

| Minutolo 2016 [30] | Hemodialysis | Center-based cohort study |

Biosimilar epoetin alfa Biosimilar epoetin-zeta |

36 weeks | 11 nonprofit Italian dialysis centers | Thirty-five percent of patients switched experienced dose escalation |

| Glintborg 2017 [16] | Rheumatology | Registry/National database | Biosimilar infliximab | 1 year | Danish quality registry, DANBIO | The mean rate of days with services provided was 5.4 before the switch and 5.7 after switch (p = 0.0003) |

| Peck 2017 [25] | Multiple myeloma, non-Hodgkin lymphoma | Center-based cohort study | Biosimilar filgrastim | 1 year | Hospital data | Use of Plerixafor (bone marrow stimulant) was higher in the biosimilar G-CSF group compared with the originator product (18 vs. 5 patients) |

| Phillips 2017 [18] | All authorized indications | Registry/National database | Biosimilar infliximab | 1 year | Turkish healthcare administrative database | Patients who switched to CT-P13 had higher outpatient (€86.6 vs. €58.3; p = 0.005), inpatient (€20.6 vs. €9.3; p = 0.313) and pharmacy costs (€474.2 vs. €427.9; p = 0.371), which resulted in significantly higher total health care costs (€646.8 vs. €528.0; p = 0.046) compared to patients who continued infliximab |

| Plevris 2017 [29] | IBD | Center-based cohort study | Biosimilar infliximab | NR | Gastrointestinal units, center data | Nine percent of patients switched experienced dose escalation |

| Ratnakumaran 2017 [32] | CD, UC | Center-based cohort study | Biosimilar infliximab | 1 year | Hospital data | Six percent of patients switched experienced dose escalation |

| Rodriguez 2017 [28] | IBD (CD and UC) | Center-based cohort study | Biosimilar infliximab | 1 year | Hospital data | Eleven percent and 13 percent of patients switched had surgery and used steroid after the non-medical switch |

| St. Clair Jones 2017 [31] | IBD (CD and UC) | Center-based cohort study | Biosimilar infliximab | 6 months | Hospital data | Of switch patients, 11.3 percent experienced dose escalation and a payment was negotiated to fund the switch |

| Szlumper 2017 [19] | Rheumatology | Center-based cohort study | Biosimilar etanercept | 7 months | Biologic registry | Three switchers requested face-to-face consultations on use of delivery device; all potential switchers were invited to face-to-face switching clinic with specialist pharmacist and nurse |

| Barnes 2018 [23] | RA, AS, PA | Interview | Biosimilar etanercept | NR | Interview | Staff spent 320–1076 additional hours on the non-medical switch across the four centers |

| Glintborg 2018 [17] | RA, PA, AS | Registry/National database | Biosimilar infliximab | 1 year | DANBIO, Danish National Patient Registry |

The included patients had 39 more outpatient visits within 6 months after the switch than before Total days with services were 4131 before (mean 5.4 days, SD 2.8) and 4400 after switch (mean 5.8 days, SD 2.8) (p < 0.01, paired t test). After the switch, 259 patients (34%) had fewer (mean − 2.4, SD 1.7), 169 patients (22%) had the same and 341 patients (45%) (mean 2.6, SD 2.0) had more days with services than before switch Patients on average had more phone consultation (1.17 vs. 1.03, p = 0.03), patient guidance (0.49 vs. 0.35, p < 0.01), intravenous medication (0.11 vs. 0.03, p < 0.01), clinical investigation (0.47 vs. 0.31, p < 0.01), clinical control (2.26 vs. 2.08, p < 0.01) and observation (0.22 vs. 0.17, p < 0.01) within 6 months after switch |

| Nisar 2018 [27] | RA | Center-based cohort study | Biosimilar rituximab | 1 year | Hospital data |

Two patients (8%) experienced emergency department visits after switching 5 (20%) had severe serum sickness reaction within the 1st week of the second dose and lost response Four (17%) requested to return to the originator |

| Peral 2018 [20] | RA | Simulation study | Biosimilar etanercept | 1 year | DANBIO registry, survey of 30 rheumatologists in Spain | The non-medical switch is associated with treatment adjustment costs, including monitoring, hospitalization and other healthcare costs |

| Rodriguez 2018 [26] | CD, UC, AS, RA | Center-based cohort study | Biosimilar infliximab | 11 months | Hospital data | One patient required treatment intensification; a total of four patients required an increased dose of immunomodulatory drugs |

| Shah 2018 [21] | RA | Center-based cohort study | Biosimilar etanercept | 1 year | Hospital data | For RA patients treated with high intensity etanercept to switch to etanercept biosimilar, 2 days of pharmacists’ time were required per week for 6 months, costing about €22,294 |

| Zahorian 2018 [22] | IBD (CD and UC) | Center-based cohort study | Biosimilar infliximab | NR | Pharmacists’ experience and hospital data | Pharmacists spent an average of 5–10 min on the phone per patient providing education and answering questions to assist the switching process |

AS ankylosing spondylitis, CD Crohn’s disease, HRU healthcare resource utilization, IBD inflammatory bowel disease, NMS non-medical switch, NR not reported, PA psoriatic arthritis, RA rheumatoid arthritis, SD standard deviation, UC ulcerative colitis

Table 3.

Post-NMS drug costs

| Citations | Diseases | Study type | Time horizon | Switch populationa | Drug costs (total €) | Annualized drug costs (€/person/year) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jha 2015 [47] | RA, AS, IBD (CD and UC), PsO, PA | Simulation study | 1 year | 3,750,611 | 3.0–34.5 million cost reduction | 7–21 cost reduction |

| Bocquet 2016 [51] | Gastroenterology, rheumatology, dermatology and others | Simulation study | 1 year | 5483 |

20% discount: 7.8 million cost reduction 30% discount: 11.7 million cost reduction |

20% discount: 1427 cost reduction 30% discount: 2141 cost reduction |

| Shah 2016 [53] | RA | Simulation study | 1 year | 7343 |

Infliximab: 37,115,928 cost reduction Adalimumab: 28,599,516 cost reduction |

Infliximab: 5055 cost reduction Adalimumab: 3895 cost reduction |

| Dyball 2017 [36] | RA | Center-based cohort study | NR | 38 | 29,428 cost reduction | 774 cost reduction |

| Gomez 2017 [56] | Rheumatology, dermatology, gastroenterology | Simulation study | 1 year | 326 | 784,270 cost reduction | 2406 cost reduction |

| Ratnakumaran 2017 [32] | IBD (CD and UC) | Center-based cohort study | 1 year | 191 | > 1.11 million cost reduction | > 5812 cost reduction |

| Razanskaite 2017 [35] | IBD (CD and UC) | Center-based cohort study | 1 year | 143 | 565,905-848,858 cost reduction | 3957–5936 cost reduction |

| Rodriguez 201 7 [28] | IBD (CD and UC) | Center-based cohort study | 1 year | 72 | 248,716 cost reduction | 3454 cost reduction |

| Garcia-Fernandez 2018 [58] | Gastroenterology, rheumatology, dermatology and other diseases | Center-based cohort study | 8 months | 76 | 62,692 cost reduction | 1237 cost reduction |

| Husereau 2018 [42] | IBD (CD) | Simulation study | 10 years | NR | 31,042 cost reduction | 3104 cost reduction |

| Mora 2018 [61] | Gastroenterology and dermatology | Center-based cohort study | 1 year | 10 |

Total: 38,237 cost reduction Gastroenterology: 25,037 cost reduction Dermatology: 13,200 cost reduction |

Overall average: 3824 cost reduction Gastroenterology: 6259 cost reduction Dermatology: 2200 cost reduction |

| O’Brien 2018 [62] | IBD | Center-based cohort study | 8 months | 20 | 15–45% discount on biosimilar price: 77,953–183,189 cost reduction |

15% discount on biosimilar price: 5846 cost reduction 45% discount on biosimilar price: 13,739 cost reduction |

| Rodriguez 2018 [26] | IBD (CD and UC), RA and AS | Center-based cohort study | 11 months | 48 | 73,476 cost reduction | 1670 cost reduction |

| Shah 2018 [21] | RA | Center-based cohort study | 1 year | 151 | 557,350 cost reduction | 3691 cost reduction |

| Valido 2018 [37] | RA, SA and PA | Center-based cohort study | 1 year | 60 | 26.4% cost reduction | 26.4% cost reduction |

| Abraham 2014 [64] | DLBCL, colorectal cancer, breast cancer | Simulation study | 15 weeks | 100,000 | 120,968,327 cost reduction | NA |

| Jha 2015 [46, 47] | IBD (CD and UC) | Simulation study | 1 year | NR |

Switch population incurred cost reduction CD 0.7–16.4 million UC 0.3–5.4 million |

NA |

| Sun 2015 [65] | Breast cancer, DLBCL | Simulation study | 14 days | 10,000 | 10%, 20%, 30%, 40%, 100% conversion rate, annual cost reductions 1.5, 3, 4.5, 6, 7.5, 15 million | NA |

| Bhattacharyya 2016 [50] | RA and PsO | Simulation study | 1 year | 27,052 | 5.7–16.9 million cost reduction | NA |

| Claus 2016 [70] | All authorized indications | Simulation study | 5 years | NR |

20% switch: Infliximab: 772,630 cost reduction Filgrastim: 106,895 cost reduction Follitropine alfa: 19,598 cost reduction Epoetin alfa: 7469 cost reduction 100% switch: Infliximab: 7,910,767 cost reduction Filgrastim: 534,474 cost reduction Follitropine alfa: 97,988 cost reduction Epoetin alfa: 37,343 cost reduction |

NA |

| Trancart 2016 [54] | RA | Simulation study | 3 years | 45,903 | 28.9 million cost reduction | NA |

| Alexandre 2017 [55] | RA | Simulation study | 5 years | 943–1571 | 4.1–6.9 million cost reduction | NA |

| McBride 2017 [67] | Chemotherapy-induced (febrile) neutropenia | Simulation study | 5, 7, 11, 14 days | 20,000 |

Cost reduction per cycle of filgrastim-sndz over filgrastim 5 days: 6,263,133 7 days: 8,768,386 11 days: 879,435,766 14 days: 17,536,772 |

NA |

| McBride 2017 [68] | Chemotherapy induced neutropenia | Simulation study | 1–14 days | 20,000 | 6.2–17.6 million cost reduction | NA |

| McBride 2017 [66] | Chemotherapy-induced (febrile) neutropenia prophylaxis | Simulation study | Chemotherapy of 1 or 6 cycles | 20,000 |

Biosimilar vs. Neupogen: 164–2158 cost reduction Biosimilar vs. Neulasta: 541–11,971 cost reduction |

NA |

| Peck 2017 [25] | Multiple myeloma, NHL | Center-based cohort study | 1 year | 50 | 2676 cost increase | NA |

| Ravonimbola 2017 [69] | Obstetrics/gynecology | Simulation study | NR | 100 |

Follitropin Alfa biosimilar 1: 25,900 cost reduction Follitropin Alfa biosimilar 2: 27,900 cost reduction |

NA |

| Reichardt 2017 [71] | NR | Simulation study | NR | NR | 16,848 cost reduction | NA |

| St. Clair Jones 2017 [31] | IBD (CD and UC) | Center-based cohort study | 6 months | 71 | 249,693 cost reduction | NA |

| Szlumper 2017 [19] | Rheumatology | Center-based cohort study | 7 months | 80 | 155,947 cost reduction | NA |

| Healy 2018 [59] | IBD (Pediatric) | Center-based cohort study | 1 year | 60 | 278,675–306,543 cost reduction | NA |

| Ma 2018 [60] | Rheumatology | Center-based cohort study | 6 months | 50 | 732,671 cost reduction | NA |

AS ankylosing spondylitis, CD Crohn’s disease, DLBCL diffuse large b-cell lymphoma, IBD inflammatory bowel disease, NHL non-Hodgkin lymphoma, NMS non-medical switching, NR not reported, PA psoriatic arthritis, PsO psoriasis, RA rheumatoid arthritis, r-hFSH recombinant human follicle-stimulating hormone, SA spondylarthritis, UC ulcerative colitis

aSwitch population refers to patients who switched from biologic originators to biosimilar

This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Results

Study Selection

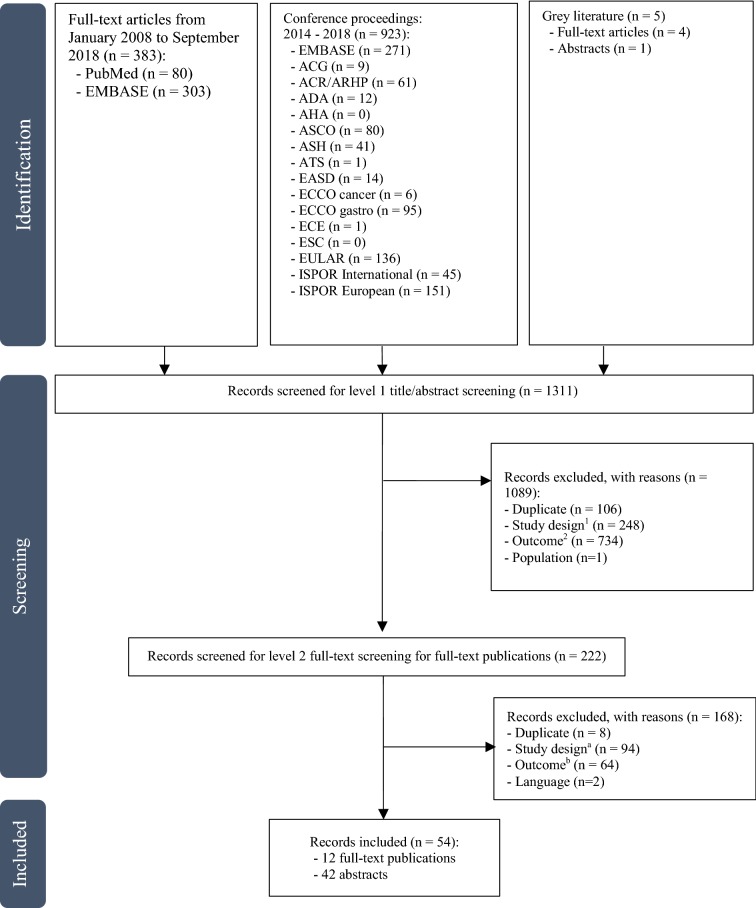

A total of 1311 studies were retrieved for screening during the literature search: 383 were full-text articles, 923 were conference proceedings and five were gray literature publications (Fig. 1). After screening, 54 studies met the inclusion criteria: 12 full-text articles and 42 conference proceedings (Table 1).

Fig. 1.

PRISMA diagram. ACG American College of Gastroenterology Annual Scientific Meeting, ACR/ARHP American College of Rheumatology Annual Meeting, ADA American Diabetes Association Scientific Sessions, AHA Scientific Sessions of American Heart Association, ASCO American Society of Clinical Oncology Annual Meeting, ASH American Society of Hematology Annual Meeting, ATS American Thoracic Society International Conferences, EASD Annual Meeting of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes, ECCO cancer European Cancer Congress, ECCO gastro European Crohn’s and Colitis Organization Annual Congress, ECE European Congress of Endocrinology, ESC European Society of Cardiology Annual Congress, EULAR The European League Against Rheumatism Annual Congress, ISPOR International International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research Annual International Meeting, ISPOR European International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research Annual European Congress. aExclusions by study design consisted of studies that were not related to non-medical switching. bExclusions by outcomes consisted of studies that did not report outcomes related to costs or healthcare resource utilization associated with NMS

Study Characteristics

The characteristics of the 54 publications were summarized in Table 1. Of these identified studies, 23 (43%) were budget impact models, simulations or cost calculation studies; 26 (48%) were medical center-based cohort studies; 3 (6%) were national database analyses; 1 (2%) was an interview study; 1 (2%) was a policy review. Infliximab biosimilar was most commonly reported (n = 26; 48%), followed by etanercept biosimilar (n = 12; 22%) and granulocyte-colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) biosimilar (n = 5; 9%). Studies of other biosimilars were less frequent, including erythropoiesis-stimulating agent (ESA) biosimilars (n = 2; 4%), adalimumab biosimilar (n = 1, 2%), follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) biosimilar (n = 1, 2%), rituximab biosimilar (n = 1, 2%) and somatropin biosimilar (n = 1; 2%); two studies (4%) included multiple biosimilars; three studies (6%) did not report which particular biosimilar(s) were studied.

Most of the studies focused on rheumatology, dermatology or gastroenterology (n = 40; 74%), followed by various types of cancer including non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL), multiple myeloma, colorectal and breast cancer (n = 6; 11%). Studies in other therapeutic areas were rather sporadic, including hemodialysis (n = 1; 2%), pediatric growth disturbances (n = 1; 2%) and obstetrics/gynecology (n = 1; 2%); five studies (9%) did not report a specific disease area. Depending on the study type, the time horizon and total sample size of the identified publications varied substantially, ranging from 1 day to 5 years and from 18 to 3,750,611 patients, respectively.

Post-NMS HRU and HRU-Related Costs

Seventeen studies reported real-world HRU or HRU-related costs (Table 2). Among them, three were national database studies (two in Denmark [16, 17] and one in Turkey [18]) and all of these three studies reported higher HRU and HRU-related costs after NMS than before NMS based on observed data. The Denmark study enrolled 769 patients with rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis or ankylosing spondylitis and reported that patients on average had 5.4 outpatient visits in the 6 months before NMS and 5.7 outpatient visits after NMS from infliximab originator to biosimilar (p = 0.0003) [16]. An update of the Denmark study reported 39 more outpatient visits within 6 months after NMS in the same population. In addition, patients on average had more phone consultations (1.17 vs. 1.03, p = 0.03), patient guidance (0.49 vs. 0.35, p < 0.01), intravenous medication (0.11 vs. 0.03, p < 0.01), clinical investigation (0.47 vs. 0.31, p < 0.01), clinical control (2.26 vs. 2.08, p < 0.01) and observation (0.22 vs. 0.17, p < 0.01) within 6 months after switch though the immediate cost consequences of NMS were not substantial [17]. The Turkey study focused on costs and reported that inpatient costs were €9 per patient 1 year before NMS and €21 per patient per year after NMS (p = 0.313); outpatient costs were €58 per patient 1 year before NMS and €87 per patient per year after NMS (p < 0.01); pharmacy costs were €428 per patient 1 year before NMS and €474 per patient per year after NMS (p = 0.371); the total healthcare costs were €528 per patient 1 year before NMS and €647 per patient per year after NMS, an average increase of €119 (23%) per patient per year (p = 0.046) [18].

Thirteen medical center-based cohort studies reported post-NMS treatment costs or medical services (Table 2). Specifically, these studies reported more NMS consultations and outpatient visits [17, 19–23], post-NMS visits or phone consultations for patients experiencing injection-site pain [24], post-NMS medication usage [17, 25, 26], post-NMS loss of response and emergency department visit [27], post-NMS surgery rate (11%) [28], post-NMS steroid use (13%) [28] and post-NMS biosimilar dose escalation (6–35.4%) [26, 29–32]. Nine reported patients discontinued the biosimilar and switched back to the originator [24, 27, 29, 31, 33–37]. In addition, semi-structured one-on-one interviews among staff members involved in an NMS of the originator etanercept to its biosimilar at four rheumatology centers in the UK reported that providers spent 320–1076 additional hours on the NMS process for 149–180 patients per center [38].

NMS-Related Drug, Healthcare and Management Costs

A total of 48 studies estimated NMS-related costs, including 32 estimating drug cost only, 10 estimating healthcare cost without specifying a detailed breakdown, 1 reporting both drug and unspecified healthcare costs and 5 estimating NMS setup and managing costs. Among these studies, only the Turkey registry study reported observed real-world total healthcare costs as well as HRU-related costs that were summarized previously (Table 2).

For the 33 studies reporting post-NMS expected drug cost reduction, 18 were simulation or modeling studies and 15 were center-based cohort studies (Table 3). The drug cost reduction was estimated to range from €164 to €879 million over different sizes of switch populations and varying lengths of follow-up. Considering the substantial variations in study designs, sample size and duration of follow-up, annualized post-NMS drug cost reductions were calculated for 15 studies with a follow-up period > 1 year and available cohort size, resulting in €7 to €13,739 per patient per year (Table 4).

Table 4.

Annualized cost difference between post- and pre-NMS

| Citations | Diseases | Study type | Biosimilar | Time horizon | Switch populationa (N) | Cost difference after vs. before NMS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Observed annual cost difference per patient (€/person/year) | ||||||

| Phillips 2017 [18] | All authorized indications | Registry/National database | Biosimilar infliximab | 1 year | 136 | 119 cost increase per patient |

| Anticipated annual cost difference per patient (€/person/year) | ||||||

| Peral 2018 [20] | RA | Simulation study | Biosimilar etanercept | 1 year | NR | 1215 cost increase per patient |

| Anticipated total cost difference (€) | ||||||

| Flodmark 2013 [24] | Pediatric growth disturbances | Center-based cohort study | Biosimilar somatropin | About 3 years | 98 | 730,000 cost reduction |

| Ala 2016 [48] | IBD (CD) | Center-based cohort study | Biosimilar infliximab | 6 months | 21 | 305,326 cost reduction |

| Rahmany 2016 [52] | IBD (CD and UC) | Center-based cohort study | Biosimilar infliximab | 6 months | 88 | 749,437 cost reduction |

| Sheppard 2016 [34] | Rheumatology | Center-based cohort study | Biosimilar infliximab | 1 year | 25 | 82,528 cost reduction |

| Plevris 2017 [29] | IBD (CD and UC) | Center-based cohort study | Biosimilar infliximab | NR | 160 | 791,437 cost reductions |

| Szlumper 2017 [19] | Rheumatology | Center-based cohort study | Biosimilar etanercept | 7 months | 80 | 155,947 cost reductions |

| Szlumper 2017 [57] | PsO | Center-based cohort study | Biosimilar etanercept | 3 months | 17 | 154,492 cost reductions |

| Ma 2018 [60] | Rheumatology | Center-based cohort study | Biosimilar etanercept | 6 months | 50 | 174,628 cost reductions |

| Healy 2018 [59] | IBD (Pediatric) | Center-based cohort study | Biosimilar infliximab | 1 year | 60 | 278,675–306,543 cost reductions |

Costs types or components considered were not defined or reported from the included studies. For studies specified the associated population size and time frame to the reported cost difference, annualized and personalized cost differences were imputed

AS ankylosing spondylitis, CD Crohn’s disease, DLBCL diffuse large b-cell lymphoma, IBD inflammatory bowel disease, NHL non-Hodgkin lymphoma, NMS non-medical switching, NR not reported, PA psoriatic arthritis, PsO psoriasis, RA rheumatoid arthritis, r-hFSH recombinant human follicle-stimulating hormone, SA spondylarthritis, UC ulcerative colitis

aSwitch population refers to patients who switched from biologic originators to biosimilar

Among the five studies estimating NMS setup and managing costs, one modeling study expected cost increases related to NMS planning activities ranging from €14,088 to €17,028 and NMS management from €7775 to €68,427 per medical center [38]. One simulation study reported an estimated short-term cost increase of €21,867 per medical center for the NMS program and subsequent administrative support from the perspective of rheumatology centers in the UK [39]. Additionally, an overall cost associated with the switching process was estimated to be €2358 per person, including €106 for patient selection and contracting based on a budget impact model from a UK perspective [40]. Another simulation study reported the estimated short-term NMS costs of €57.48 per patient from the perspective of providers in the US [41]. Finally, an interview study [23] reported NMS costs associated extra staff time. The per-person NMS cost needed to pay healthcare practitioners ranged from €217 to €448.

Discussion

As more biosimilars are introduced into the market worldwide, biosimilar NMS uptake is expected to increase because of the perceived potential cost reduction from a discounted drug price. However, biosimilar medications are approved under the premise of biosimilarity rather than interchangeability. While continued efforts are made to evaluate clinical outcomes associated with biosimilar NMS (e.g., development of anti-drug antibody, immunogenic response in the context of immunosuppressant therapy), it has become increasingly important to understand the real-world economic impact of biosimilar NMS on HRU and costs from a holistic perspective beyond drug price.

Furthermore, the market pertaining to originator biologics and biosimilars is volatile under the current economic and political climate worldwide. The future of the relationship between originators and biosimilars may be reshaped for factors such as prices and accesses that are still evolving. To the extent possible, this systematic literature review focused on the economic impact such as HRU and costs related to biosimilar NMS over the past 10 years. The review of the economic implications of biosimilar NMS found more data on the anticipated post-NMS cost estimates than on the real-world observed post-NMS costs or HRU. There were also more simulation studies on NMS implications due to drug acquisition costs rather than providing costs estimates comprised of all health care services required during and after NMS. In fact, observed real-world HRU and/or HRU-related costs with a sufficient follow-up period were only reported in three studies using national registry databases. Because biosimilars are not identical copies of their originator biologics, drug price should not be the only determining factor when assessing the economic impact of NMS, unlike the case of small-molecule drug generics [42]. Long-term observations of all healthcare service needs during the post-NMS period could provide a more comprehensive evaluation of the economic impact of NMS. Although existing clinical trials demonstrated similar efficacy and safety of the approved biosimilars, variation exists when it comes to individual patients or specific medical conditions. Monitoring and trial-and-error adjustments are common for any medication switching (including those due to medical reasons such as loss of response). In the situation of NMS, some patients may respond differently to a biosimilar than its originator and potentially generate additional NMS-related costs. For example, after NMS, patients could require additional trial-and-error dosing adjustments and may necessitate additional laboratory tests or follow-up visits to monitor post-NMS status.

In addition, physicians, nurses, patients and healthcare administrators may need to be trained to educate patients on biosimilar NMS, offering support if NMS-related questions from these patients come up and following up with proper monitoring after the initiation of NMS; new administrative procedures may also need to be put in place to initiate, process and reimburse the biosimilar. All these activities are likely to generate additional costs due to biosimilar NMS. In two recent modeling studies, over a 3-month period, biosimilar NMS in patients with autoimmune diseases was estimated to increase healthcare costs for both payers and providers, mostly due to extra time needed during office visits and additional laboratory tests, procedures and follow-up visits [39, 41]. While additional monitoring and administrative costs may be partially absorbed by biosimilar manufacturers or healthcare providers, the cost amount may increase over time if a patient underwent more than one NMS because of lack of response, low treatment adherence or adverse events. As a result, in cases of multiple NMS, these seemingly one-time costs may become long-term costs that patients and payers need to bear, likely reducing the NMS cost reduction associated with the lower drug costs of biosimilars.

It is unclear whether rebates or patient support programs for biologic originators were accounted for when studies evaluated drug cost differences between biologic originators and biosimilars. According to one study identified during our literature review, rebates for some originators can already reach up to 50% of their list price, which could result in a similar or even lower price range of its biosimilar [43]. It is also uncertain whether savings to payers, because of the reduced drug price, may be translated to savings for patients if the biosimilar manufacturers do not offer or offer a less generous copayment assistance program.

Besides economic data, to assuage any concerns that patients and physicians may have, more real-world clinical data on the safety and effectiveness of biosimilars compared with their originator biologics are also needed for the short and long term and across indications. Debates on this topic remain. For instance, a recent systematic literature review of post-NMS clinical outcomes suggests that the risk of immunogenicity-related safety issues or diminished efficacy is similar before and after NMS based on a limited number of real-world studies pertaining to the safety of NMS [13]. On the contrary, concerns were raised for the lack of sufficient evidence to support the safety and efficacy of NMS at least for some biosimilars [42]. In the present review, we found that, among the limited real-world studies, after NMS, higher rates of surgery, concomitant medication use, biosimilar discontinuation, switch back to the originator biologic or switch to other biologics were reported. It should be noted that the results of this literature review are consistent with a recent assessment made by Husereau et al. [42] that existing data are insufficient for payers and health technology assessment (HTA) agencies to make decisions regarding biosimilar NMS.

Limitations

This study is subject to some limitations. As with any systematic literature review, the variability in the methodologies used by the identified studies may limit the interpretation and generalizability of the synthesized results. Conducting a meta-analysis and generating a pooled estimate of the impact of NMS on HRU and costs was not possible because of methodologic differences across studies. Furthermore, it should be noted that the skewed proportion of studies considering NMS for the infliximab biosimilar may limit the generalizability of the current results to NMS involving other biologics. We found that switching from the originator infliximab to its biosimilar was most frequently studied, likely because it was one of the first approved biosimilars and several versions are currently on the market in different countries [44, 45]. Indeed, almost half of the identified studies (n = 26; 48%) evaluated the infliximab biosimilar NMS, albeit with substantial variations in study design and estimates of the NMS economic impact. Overall, a limited number of studies evaluated the economic impact of NMS and even fewer had real-world HRU estimation. Among the identified studies, most are conference abstracts. Quality assessment for conference proceedings may have not undergone as thorough a peer-review process as a manuscript published by a journal. No study quality classification was made for this systematic literature review because of the lack of validated instrument for studies analyzing healthcare costs and HRU. Moreover, the majority of included studies were either abstracts from conference proceedings or simulation studies with heavy assumptions. Future research providing more real-world evidence regarding biosimilar NMS as well as studies developing and validating instruments to evaluate the quality of such studies is warranted.

Conclusion

The future concerning originators vs. biosimilars continues evolving and requires close monitoring of this dynamic field. With a focus on the economic impact such as HRU and costs over the past 10 years, this systematic literature review found that the overall economic impact of biosimilar NMS remains uncertain. Drug costs continue to be the sole focus of most modeling and medical center-based studies. Only three real-world database studies reported observed economic consequences of biosimilar NMS with two of them showing an increase in the HRU and costs associated with biosimilar NMS and one suggesting no immediate cost impact. More real-world studies that include both drug costs and other NMS-related medical and administrative costs are needed to quantify the full economic impact of NMS in both the short and long term. In particular, better understanding the upfront costs required to prepare patients and prescribers for biosimilar NMS to manage the expectations (e.g., patient education and support, trainings to healthcare professionals) can be important, which may help mitigate the potential consequences associated with biosimilar NMS. Collectively, this information would allow payers, physicians and policy makers to more comprehensively assess the implications of biosimilar NMS.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We thank Cheryl Xiang and Xinglei Cai, employees of Analysis Group, Inc., during the conduct of this study, for the help with data extraction and analysis.

Funding

Sponsorship for this study was funded by AbbVie. The sponsor was involved in study design, data interpretation, manuscript development and decision to submit the manuscript for publication. Article processing charges and the Open Access fee were not received by the journal for the publication of this article. All authors had full access to all of the data in this study and take complete responsibility for the integrity of the data and accuracy of the data analysis.

Medical Writing and Editorial Assistance

Medical writing assistance in the preparation of this article was provided by Dr. Cinzia Metallo and Dr. Su Zhang of Analysis Group, Inc. Support for this assistance was funded by AbbVie.

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Disclosures

Yifei Liu is an Associate Professor of the Division of Pharmacy Practice and Administration, The University of Missouri-Kansas City School of Pharmacy, Kansas City, MO, USA, and is a member of the journal’s Editorial Board. Min Yang is an employee of Analysis Group, Inc., which has received consultancy fees from AbbVie for this study. Eric Q. Wu is an employee of Analysis Group, Inc., which has received consultancy fees from AbbVie for this study. Jessie Wang is an employee of Analysis Group, Inc., which has received consultancy fees from AbbVie for this study. Vishvas Garg is an employee of AbbVie and may own stocks or stock options in AbbVie. Martha Skup is an employee of AbbVie and may own stocks or stock options in AbbVie.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Data Availability

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Footnotes

Enhanced Digital Features

To view enhanced digital features for this article go to 10.6084/m9.figshare.8131589.

References

- 1.US Pharmacist. The use of biologics in cancer therapy. https://www.uspharmacist.com/article/the-use-of-biologics-in-cancer-therapy. 2010. Accessed Dec 7 2018.

- 2.Morrow T, Felcone LH. Defining the difference: what makes biologics unique. Biotechnol Healthc. 2004;1(4):24–29. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Declerck P, Danesi R, Petersel D, Jacobs I. The language of biosimilars: clarification, definitions, and regulatory aspects. Drugs. 2017;77(6):671–677. doi: 10.1007/s40265-017-0717-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bridges SL, Jr, White DW, Worthing AB, Gravallese EM, O’Dell JR, Nola K, et al. The science behind biosimilars: entering a new era of biologic therapy. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2018;70(3):334–344. doi: 10.1002/art.40388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Generics and Biosimilars Initiative (GaBI). Biosimilars approved in Europe. http://www.gabionline.net/Biosimilars/General/Biosimilars-approved-in-Europe. 2017. Accessed Dec 7 2018.

- 6.Grabowski H, Guha R, Salgado M. Biosimilar competition: lessons from Europe. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2014;13:99. doi: 10.1038/nrd4210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mehr SR, Brook RA. Factors influencing the economics of biosimilars in the US. J Med Econ. 2017;20(12):1268–1271. doi: 10.1080/13696998.2017.1366325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.FiercePharma. Targeting a $5B brand, Samsung and Merck launch Remicade biosimilar at 35% discount. https://www.fiercepharma.com/pharma/samsung-merck-launch-remicade-biosim-at-35-discount. 2017. Accessed Dec 7 2018.

- 9.Posner J, Griffin JP. Generic substitution. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2011;72(5):731–732. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2011.03920.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liberman JN, Roebuck MC. Prescription drug costs and the generic dispensing ratio. J Manag Care Pharm. 2010;16(7):502–506. doi: 10.18553/jmcp.2010.16.7.502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grabowski HG, Guha R, Salgado M. Regulatory and cost barriers are likely to limit biosimilar development and expected savings in the near future. Health Aff (Millwood) 2014;33(6):1048–1057. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2013.0862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Singh SC, Bagnato KM. The economic implications of biosimilars. Am J Manag Care. 2015;21(16 Suppl):s331–s340. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cohen HP, Blauvelt A, Rifkin RM, Danese S, Gokhale SB, Woollett G. Switching reference medicines to biosimilars: a systematic literature review of clinical outcomes. Drugs. 2018;78(4):463–478. doi: 10.1007/s40265-018-0881-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.The Biosimilars Council. Biosimilars in the United States. http://biosimilarscouncil.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/Biosimilars-Council-Patient-Access-Study.pdf. 2017. Accessed Dec 7 2018.

- 15.Wells G, Shea B, O’Connell D, Peterson J, Welch V, Losos M, et al. The Newcastle-Ottawa scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analysis. Ottawa: The Ottawa Health Research Institute; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Glintborg B, Sørensen J, Hetland ML. THU0648 use of outpatient rheumatologic health care services before and after switch from originator to biosimilar infliximab. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76(Suppl 2):450–451. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Glintborg B, Sørensen J, Hetland ML. Does a mandatory non-medical switch from originator to biosimilar infliximab lead to increased use of outpatient healthcare resources? A register-based study in patients with inflammatory arthritis. RMD Open. 2018;4(2):e000710. doi: 10.1136/rmdopen-2018-000710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Phillips K, Juday T, Zhang Q, Keshishian A. SAT0172 economic outcomes, treatment patterns, and adverse events and reactions for patients prescribed infliximab or ct-p13 in the turkish population) Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76(Suppl 2):835. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Szlumper C, Topping K, Blackler L, Kirkham B, Ng N, Cope A, et al. Switching to biosimilar etanercept in clinical practice. Rheumatology. 2017;56(suppl_2):139. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kex062.226. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Peral C, Valderrama M, Montoro M, Gomez S, Tarallo M. Cost methods including CE/CB/CU, resource use, productivity, valuation and health econometrics (CS) Barcelona: ISPOR; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shah K, Flora K, Penn H. Cost effectiveness of a high intensity programme (HIP) compared to a low intensity programme (LIP) for switching patients with rheumatoid arthritis to the etanercept biosimilar. Rheumatology. 2018;57(suppl_3):075. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zahorian T, Farraye F, Reich J, Noronha A, Wasan S, Shah B. Successful transition to an infliximab biosimilar at an Academic Hospital. Philadelphia: American College of Gastroenterology; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Barnes T, Wong E, Thakrar K, Douglas K, Glen F, Young-Min S, et al. 106 Switching stable rheumatology patients from an originator biologic to a biosimilar: resource cost in the UK. Rheumatology. 2018;57(suppl_3):075. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/key075.330. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Flodmark CE, Lilja K, Woehling H, Jarvholm K. Switching from originator to biosimilar human growth hormone using dialogue teamwork: single-center experience from Sweden. Biol Ther. 2013;3:35–43. doi: 10.1007/s13554-013-0011-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Peck R. Peripheral blood stem cell mobilisation: an experience of switching to biosimilar G-CSF. 2017; Glasgow.

- 26.Rodríguez JR. 5PSQ-084 Safety and effectiveness of switching to infliximab biosimilar in digestive and rheumatological pathology. Eur J Hosp Pharm. 2018;25(Suppl 1):A203–A204. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nisar MK. 292 Switching to biosimilar rituximab: a real world study. Rheumatology. 2018;57(suppl_3):075. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rodríguez Glez G, Díaz Hernández L, Morales Barrios J, Vela González M, Tardillo Marín C, Viña Romero M, et al. P629 Efficacy, safety and economic impact of the switch to biosimilar of infliximab in inflammatory bowel disease patients in clinical practice: results of one year. J Crohn’s Colitis. 2017;11(suppl_1):S402. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjx002.753. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Plevris N, Deekae A, Jones GR, Manship TA, Noble CL, Satsangi J, et al. A novel approach to the implementation of biosimilar infliximab CT-P13 for the treatment of IBD utilising therapeutic drug monitoring: the Edinburgh Experience. Gastroenterology. 2017;152(5):S385. doi: 10.1016/S0016-5085(17)31528-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Minutolo R, Borzumati M, Sposini S, Abaterusso C, Carraro G, Santoboni A, et al. Dosing penalty of erythropoiesis-stimulating agents after switching from originator to biosimilar preparations in stable hemodialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis. 2016;68(1):170–172. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2016.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Clair Jones A, Smith M. P527 Infliximab biosimilar switching program overseen by specialist pharmacist saves money, realises investment and optimises therapy. J Crohn’s Colitis. 2017;11(suppl_1):S348. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjx002.651. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ratnakumaran R, To N, Gracie DJ, Selinger CP, O’Connor A, Clark T, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of initiating, or switching to, infliximab biosimilar CT-P13 in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD): a large single-centre experience. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2018;53(6):700–707. doi: 10.1080/00365521.2018.1464203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gutermann L, Apparuit M, Boissinot L, Bruneau A, Zerhouni L, Conort O, et al. CP-150 Evaluation of infliximab (remicade) substitution by infliximab biosimilar (inflectra): cost savings and therapeutic maintenance. Eur J Hosp Pharm. 2017;24(Suppl 1):A67–A68. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sheppard M, Hadavi S, Hayes F, Kent J, Dasgupta B. AB0322 preliminary data on the introduction of the infliximab biosimilar (CT-P13) to a real world cohort of rheumatology patients. Ann Rheum Dis. 2016;75(Suppl 2):1011. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-eular.5252. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Razanskaite V, Bettey M, Downey L, Wright J, Callaghan J, Rush M, et al. Biosimilar infliximab in inflammatory bowel disease: outcomes of a managed switching programme. J Crohns Colitis. 2017;11(6):690–696. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjw216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dyball S, Hoskins V, Christy-Kilner S, Haque S. Effectiveness and tolerability of benepali in rheumatoid arthritis patients switched from Enbrel. Hoboken: Wiley; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Valido A, Silva-Dinis J, Saavedra MJ, Bernardo N, Fonseca JE. AB1231 Efficacy and cost analysis of a systematic switch from originator infliximab to biossimilar ct-p13 of all patients with inflammatory arthritis from a single centre. Ann Rheum Dis. 2018;77(Suppl 2):1712–1713. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Barnes T, Wong E, Thakrar K, Glen F, Young-Min S, Marchbank K, et al. The resource cost of switching stable rheumatology patients from an originator biologic to a biosimilar in the UK. Value Health. 2017;15:60. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gibofsky A, Garg V, Yang M, Qi C, Skup M. AB0416 Estimating the short-term costs associated with non-medical switching in rheumatic diseases. London: BMJ Publishing Group Ltd; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Brown C, McCann E. Cost of switching from an originator biologic (Remicade) to a biosimilar. Value Health. 2016;19(7):A581. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2016.09.1351. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gibofsky A, Skup M, Yang M, Mittal M, Macaulay D, Ganguli A. Short-term costs associated with non-medical switching in autoimmune conditions. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2018;37:97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Husereau D, Feagan B, Selya-Hammer C. Policy options for infliximab biosimilars in inflammatory bowel disease given emerging evidence for switching. Appl Health Econ Health Policy. 2018;16(3):279–288. doi: 10.1007/s40258-018-0371-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hakim A, Ross JS. Obstacles to the adoption of biosimilars for chronic diseases. JAMA. 2017;317(21):2163–2164. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.5202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.FDA. Purple book: Lists of licensed biological products with reference product exclusivity and biosimilarity or interchangeability evaluations. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/developmentapprovalprocess/howdrugsaredevelopedandapproved/approvalapplications/therapeuticbiologicapplications/biosimilars/ucm411418.htm. 2018. Accessed Dec 7 2018.

- 45.Lakatos P. European experience of infliximab biosimilars for the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;12(2):119–121. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jha A, Dunlop W, Upton A. Budget impact analysis of introducing biosimilar infliximab for the treatment of gastro intestinal disorders in five European Countries. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jha A, Upton A, Dunlop WC, Akehurst R. The budget impact of biosimilar infliximab (Remsima(R)) for the treatment of autoimmune diseases in five European Countries. Adv Ther. 2015;32(8):742–756. doi: 10.1007/s12325-015-0233-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ala K, Avery P, Wilson R, Prowse A, Shutt J, Jupp J, et al. PTU-059 early experience with biosimilar infliximab at a district general hospital for an entire Crohn’s disease patient cohort switch from remicade to inflectra. Gut. 2016;65(Suppl 1):A81. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2016-312388.145. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Becciolini A, Psachoulia E, Biggioggero M, Crotti C, Agape E, Negrini C, et al. The introduction of etanercept biosimilar in the practice of a tertiary rheumatologic Centre in Italy: a budget impact model. Value Health. 2016;19(7):A534. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2016.09.1092. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bhattacharyya S, Banerjee S, Clinton H, Faithfull G, Mendoza C. Impact of etanercept biosimilar launches on healthcare spending: a UK budget impact model for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis and chronic plaque psoriasis. Value Health. 2016;19(7):A580–A581. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2016.09.1350. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bocquet F, Fusier I, Cordonnier A, Lechat P, Paubel P. Marketing of the first biosimilar infliximab in France: what budgetary impact in the public hospitals of Paris? Presented at the Société Française de Pharmacologie et de Thérapeutique (SFPT) meeting, April 2016. http://pharmacie-hospitaliere-ageps.aphp.fr/marketing-biosimilar-infliximab-france-budgetary-impact-public-hospitals-paris/. 2016. Accessed Dec 7 2018.

- 52.Rahmany S, Cotton S, Garnish S, McCabe L, Brown M, Saich R, et al. PTH-157 The introduction of biosimilar infliximab (CT-P13) through a managed switching programme generates significant cost savings with high levels of patient satisfaction. Gut. 2016;65(Suppl 1):297. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Shah A, Mwamburi M. Modeling the budget impact of availability of biosimilars of infliximab and adalimumab for treatment for rheumatoid arthritis using published claim-based algorithm data in the United States. Value Health. 2016;19(3):A228. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2016.03.1122. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Trancart M, Lafuma A, Laurendeau C. Budget impact of etanercept biosimilars in the treatment of rheumatoid arthrisis: an analysis based on French National Claims Database. Value Health. 2016;19(7):A532–A533. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2016.09.1082. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Alexandre R, Squiassi H, Santana C. Cost minimization analysis in the switch of infliximab for its biosimilar in the Brazilian private healthcare system. Presented at the ISPOR 22nd Annual International Meeting (poster PMS37). 2017.

- 56.Gómez GC, Nicolás FG, Eguilior NY, Casariego GN, Romero MV, Molina MB, et al. CP-182 Potential economical impact of biosimilar adalimumab. Eur J Hosp Pharm. 2017;24(Suppl 1):A81–A82. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Szlumper C, Laftah Z, Smith C, Barker J, Mercer S, Benton E, et al. Switching to biosimilar etanercept in clinical practice: a prospective cohort study. Br J Dermatol. 2017;177:62. doi: 10.1111/bjd.15315. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.García-Fernandez C, Ruiz-Fuentes S, Belda-Rustarazo S, Gómez-Peña C, Morón-Romero R, Gómez-Nieto P. 2SPD-013 Economic impact of biosimilar infliximab use. Eur J Hosp Pharm. 2018;25(Suppl 1):A15. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Healy M, Crook J, Chavda C, Smith E. P35 An experience of switching paediatric inflammatory bowel disease patients on infliximab therapy to the biosimilar ‘remsima’. Arch Dis Child. 2018;103(2):e1. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ma J, Petford S, Jones L, Douglas K, John H. Audit of the clinical efficacy and safety of etanercept biosimilar to its reference product in patients with inflammatory arthritis: experience from a district general hospital in the United Kingdom. Rheumatology. 2018;57(suppl_3):075. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/key075.288. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mora AM, Rosa VG, Torres MS. 1ISG-008 Economic impact of the use of biosimilar infliximab in a second-level hospital. Eur J Hosp Pharm. 2018;25(Suppl 1):A4. [Google Scholar]

- 62.O’Brien G, Carrol D, Walshe V, Mulcahy M, Courtney G, Omahony C, et al. A cost saving measure from the utilisation of biosimilar infliximab in the Irish secondary care setting. Barcelona: ISPOR; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Shah K, Flora K, Penn H. 232 Clinical outcomes of a multi-disciplinary switching programme to biosimilar etanercept for patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology. 2018;57(suppl_3):075. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Abraham I, Han L, Sun D, MacDonald K, Aapro M. Cost savings from anemia management with biosimilar epoetin alfa and increased access to targeted antineoplastic treatment: a simulation for the EU G5 countries. Future Oncol. 2014;10(9):1599–1609. doi: 10.2217/fon.14.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sun D, Andayani TM, Altyar A, MacDonald K, Abraham I. Potential cost savings from chemotherapy-induced febrile neutropenia with biosimilar filgrastim and expanded access to targeted antineoplastic treatment across the European Union G5 countries: a simulation study. Clin Ther. 2015;37(4):842–857. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2015.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.McBride A, Abraham I, MacDonald K, Campbell K, Bikkina M, Balu S. Cost savings of conversion from filgrastim or pegfilgrastim to biosimilar filgrastim-sndz for chemotherapy-induced (febrile) neutropenia (CIN/FN) prophylaxis and expanded access to biosimilar GCSF on a budget neutral basis. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(15_suppl):e18334. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.35.15_suppl.e18334. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 67.McBride A, Campbell K, Bikkina M, MacDonald K, Abraham I, Balu S. Expanded access to obinutuzumab from cost-savings generated by biosimilar filgrastim-sndz in the prophylaxis of chemotherapy-induced (febrile) neutropenia: US simulation study. Blood. 2017;130(Suppl 1):3380. [Google Scholar]

- 68.McBride A, Balu S, Campbell K, Bikkina M, MacDonald K, Abraham I. Expanded access to cancer treatments from conversion to neutropenia prophylaxis with biosimilar filgrastim-sndz. Future Oncol. 2017;13(25):2285–2295. doi: 10.2217/fon-2017-0374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ravonimbola H, Petrica N, Maurel F, Murphy C, Doré C, Fresneau L. A cost-effectiveness analysis comparing the originator recombinant human alfa to their biosimilars follitropin alfa for the treatment of infertility. Value Health. 2017;20(9):A522. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2017.08.699. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Claus B, Simoens S, Vanhorebeek S, Commeyne S. Budget impact analysis of the introduction of biosimilars in a Belgian Tertiary Care Hospital: a simulation. Value Health. 2016;19(7):A460. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2016.09.659. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Reichardt B, Reiter G, Stamm T, Nell-Duxneuner V. THU0770-HPR Cost savings by favouring infliximab biosimilars in the eastern region of austria. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76:1494. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.