Abstract

Introduction

Pressurised metered-dose inhalers (pMDIs) are associated with global warming potential values as they contain a hydrofluoroalkane (HFA) propellant, whereas the Respimat® Soft Mist™ inhaler is propellant-free. The original disposable Respimat has recently been updated to provide a reusable device that is similar in performance and use but is more convenient to patients and reduces environmental impact. This study compared the product carbon footprint (PCF) of Respimat (both disposable and reusable) and pMDIs to understand life cycle hotspots, and also to determine the potential quantitative environmental benefits of a reusable Respimat product.

Methods

PCFs of four inhalation products—tiotropium bromide (Spiriva®) Respimat, ipratropium bromide/fenoterol hydrobromide (Berodual®) Respimat, Berodual HFA pMDI and ipratropium bromide (Atrovent®) HFA pMDI—were assessed across their whole life cycle.

Results

Data show that Respimat inhalers have a lower PCF (carbon dioxide equivalent per kilogram) than HFA pMDIs: pMDI Atrovent 14.59; pMDI Berodual 16.48; disposable Spiriva Respimat 0.78; disposable Berodual Respimat 0.78. Approximately 98% of the pMDI life cycle total is due to HFA propellant emissions during use and end-of-life phases. The impact of the material used for the Respimat product outweighs the impact of the material used to make the empty cartridge. Furthermore, compared with the single-use device over 1 month, the PCF of Spiriva Respimat was further reduced by 57% and 71% using the device with refill cartridges over 3 and 6 months, respectively.

Conclusion

Together, these data suggest that Respimat inhalers, and in particular the new reusable inhaler, can reduce the environmental impact associated with inhaler use.

Funding

Boehringer Ingelheim.

Keywords: Product carbon footprint, Pulmonary, Respimat, Reusable, Soft mist inhaler

Introduction

Pressurised metered-dose inhalers (pMDIs) are commonly used for obstructive airway diseases, but are associated with inherent limitations that may lead to low lung deposition [1]. pMDI-based inhalers are handheld, active devices comprising a mouthpiece, a valve and a metal container with the hydrofluoroalkane (HFA) liquid gas as propellant along with the formulation. When actuated, a dose is released, propelled by the HFA. These propellants are considered to be greenhouse gases (GHGs) with global warming potential (GWP) values [1, 2]. However, although HFAs and other GHGs have relatively high GWPs, the amount of emissions of these gases is dwarfed by emissions of carbon dioxide, nitrous oxide and methane [2]. The Respimat® inhalers are propellant-free, handheld devices that achieve higher drug deposition in the lungs than pMDIs [3]; they comprise a pump with a nozzle, a dose-release button, a dose indicator and a cartridge that contains the aqueous solution. At each actuation, the measured dose is forced through the nozzle system, producing two fine jets merging at a controlled angle and resulting in a unique slow-moving “soft mist” [1]. The original Respimat device was disposable; recent updates to the device have focused on making the device more patient-friendly in terms of handling and ease of use, while maintaining the aerosol performance of the original Respimat. These changes have also led to the Respimat being a reusable device, with the potential for reduced environmental impact. One way to summarise and characterise a product’s climate change impact is through the product carbon footprint (PCF), which assesses GHG emissions during a product’s life cycle. The aims of this study were to compare the PCFs of the propellant-free Respimat device with the HFA pMDIs, to understand the areas of the products’ life cycles with the highest climate change impact and to determine the potential benefits of a reusable Respimat product.

Methods

The PCFs of tiotropium bromide (Spiriva®) Respimat (both disposable and reusable),1 ipratropium bromide/fenoterol hydrobromide (Berodual®) Respimat,2 Berodual HFA pMDI3 and ipratropium bromide (Atrovent®) HFA pMDI4 were assessed across their whole life cycle (material acquisition and pre-processing, production, distribution, use and end of life). All are bronchodilators used as maintenance treatments for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) or as add-on treatments to inhaled corticosteroids for patients with asthma. Primary data were collected from relevant members of the supply chain via email using customised data collection templates. Returned data were cross-checked for completeness and plausibility using mass balance (accounting for material entering and leaving the system), stoichiometry (where the total mass of the reactants equals the total mass of the products) and internal/external benchmarking. Any gaps, outliers or inconsistencies were resolved internally. Key assumptions based on estimates were made for other inputs, e.g. shipping/transport and disposal/end of life. Reported PCFs were calculated according to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change Fifth Assessment Report on Climate Change [4], and were compliant with the Product Life Cycle Accounting and Reporting Standard [5] and specific sector guidance for pharmaceutical products [6]. PCFs were expressed as carbon dioxide equivalent (CO2eq) per kilogram, which allows “bundles” of GHGs to be expressed as a single number. The CO2eq also allows easy comparison between different “bundles” of GHGs in terms of their total potential global warming impact. CO2eqs for an input, output or process, based on activity data, emission factors and a 100-year GWP [4], were calculated as follows:

kg CO2eq = activity data (unit) × emission factor (kg GHG/unit) × GWP (kg CO2eq/kg GHG).

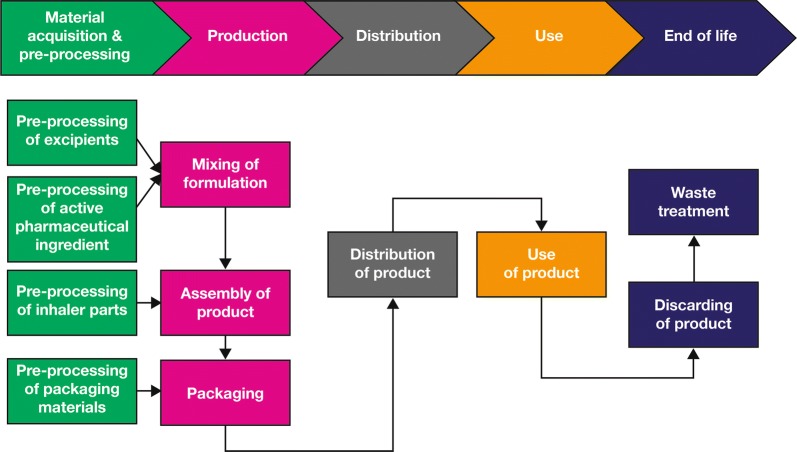

The GHGs included in the inventory were carbon dioxide (CO2), methane (CH4), nitrous oxide (N2O), sulphur hexafluoride (SF6), perfluorocarbon (PFC) and HFAs. The life cycle stages included in this study are shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Process map of Respimat and pMDI life cycle stages

PCFs were assessed over 1 month of use (also 3 and 6 months for reusable Spiriva Respimat). pMDI use was analysed as 6.6 actuations/day (200 actuations equivalent to 1-month usage). Respimat use was analysed as 2 (Spiriva) and 4 (Berodual) actuations/day, respectively; Respimat cartridges are used for 60 (Spiriva) or 120 (Berodual) actuations, sufficient for 1-month usage.5 The pMDI propellant assessed was HFA-134, which is a liquefied compressed gas at room temperature (20 °C) above a pressure of 5.72 bar [7].

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

Ethics committee approval was not required as this article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Results

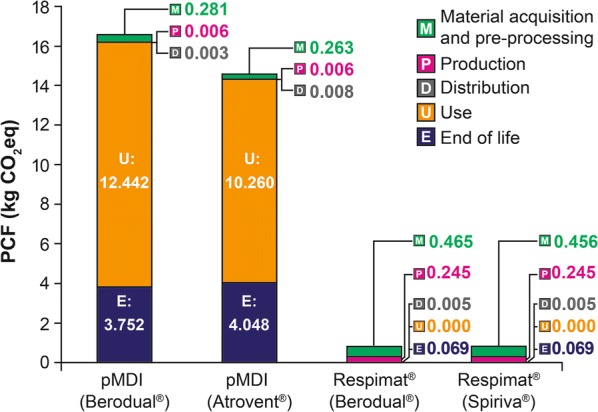

Results show that the PCFs of HFA pMDI products are approximately 20 times greater than the currently marketed disposable Respimat device (PCF [kg CO2eq]: pMDI Atrovent 14.59; pMDI Berodual 16.48; disposable Spiriva Respimat 0.78; Berodual Respimat 0.78). Atrovent and Berodual pMDI PCFs are dominated by HFA propellant emissions during use and end-of-life phases, accounting for approximately 98% of each pMDI life cycle total for each product. This is driven by HFA gas emission during use and the emission of leftover propellant gas during waste treatment (Fig. 2). The additional impact of the pMDI device (about 1%), formulation (0.8%), other materials, production process and distribution (each between 0% and 0.1%) have a minor influence on the PCF of the pMDI products. In contrast, Respimat is propellant-free; thus there is no impact of HFA (Fig. 2). The PCFs of the disposable Respimat inhaler products (Spiriva Respimat and Berodual Respimat) show that the highest contribution (around 60%) comes from the materials used in the device and cartridge parts (stainless steel, aluminium, several polymers). The second highest share (around 30%) of the PCF is due to the energy required in the production process of the inhaler. The end-of life phase (disposal of the packaging, empty cartridge and device) contributes around 8% in both cases. An additional 0.6% of the total impact is due to product distribution. The formulation has a very low impact on PCF (around 0.1% for Spiriva Respimat and around 1.1% for Berodual Respimat). The use phase has no impact, as the emission of the formulation is not included in this study; it is marginal and considered to stay in the users’ lungs. Paper products used for packaging contribute a negative value to the PCF of the product; this is due to the biogenic carbon incorporated into these materials.

Fig. 2.

PCFs of Respimat and pMDI products by life cycle stage. CO2eq carbon dioxide equivalent, PCF product carbon footprint, pMDI pressurised metered-dose inhalers

The electricity and thermal energy used during the disposable Respimat device cartridge assembly steps contribute more to the PCF than energy used during the Respimat packaging step: 0.38 and 0.08 versus 0.01 kg CO2eq, respectively.

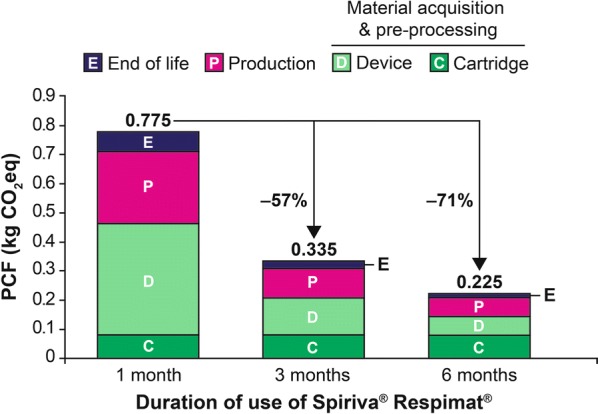

Compared with the single-use device over 1 month, the PCFs of Spiriva Respimat were further reduced by 57% and 71% to 0.34 and 0.23 kg CO2eq using the device with refill cartridges over 3 and 6 months, respectively (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Monthly contribution of each life cycle stage to the PCF of reusable Spiriva® Respimat® over 1, 3 and 6 months. CO2eq carbon dioxide equivalent, PCF product carbon footprint

Discussion

This study provides interesting and important data concerning the GWP inherent in the use of the pMDI and Respimat devices used by patients with obstructive airway diseases, including the carbon footprint of their manufacture, transportation and end-of-life disposal, as well as the contribution of the HFA propellants.

Assessments of this type necessitate the making of certain assumptions, particularly concerning transport, so that average shipping distances and transportation methods were considered. When considering the use profile, real-life data were considered as far as possible. However, variations in use behaviours lead to some uncertainties or options. For example, 6.6 inhalations per day were assumed for pMDI use, and for the Respimat, the base scenario considered was the use of one device and one cartridge for a period of 1 month. Additionally, for the disposal elements of the calculations, although the packaging and some device parts could theoretically be recycled or reused, the frequently observed disposal of the device and packaging in household waste was considered here.

Although direct comparisons cannot be definitively made, it appears that the PCFs of the propellant-based pMDIs remain many times higher than disposable Respimat products assessed in this study. The assessment suggests that the HFA propellant accounts for about 98% of the PCF of an HFA pMDI, whereas Respimat is propellant-free and therefore has a considerably lower PCF, meaning they are more environmentally sustainable than pMDIs. Since there appears to be a greater impact during production for the housing versus the empty cartridge, an opportunity exists to even further improve the PCF of Respimat with reusable options.

Whilst emissions of HFA propellants from pMDIs, along with other aerosol uses, account for a small percentage of emissions of high-GWP gasses [2], the UK government has recommended that the National Health Service should set a target that at least 50% of prescribed inhalers should be low GWP by 2022 [8].

Conclusion

Data shown here indicate that Respimat (particularly the reusable device) has a lower PCF and environmental impact, in terms of GWP, compared with pMDIs. Thus, use of the reusable Respimat device may not only provide usability benefits for patients with asthma and COPD but also has a reduced environmental impact.

Acknowledgements

Funding

This study was supported by Boehringer Ingelheim, who also funded the Rapid Service and Open Access fees. All authors had full access to all the data in this study and take complete responsibility for the integrity of the data and accuracy of the data analysis.

Editorial Assistance

Victoria Kinsley at SciMentum (a Nucleus Global company, UK) provided editorial assistance in the development of this manuscript, funded by Boehringer Ingelheim.

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take complete responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Disclosures

Thomas Bambach is an employee of Boehringer Ingelheim. Herbert Wachtel is an employee of Boehringer Ingelheim. Michaela Hänsel was an employee of Boehringer Ingelheim during the study period and is now an employee of CSL Behring GmbH.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

Ethics committee approval was not required as this article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Data Availability

The datasets obtained during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Footnotes

Spiriva® Respimat®: Spiriva (tiotropium bromide) delivered via the Respimat inhaler (both disposable and reusable devices).

Berodual® Respimat®: Berodual (fenoterol hydrobromide + ipratropium bromide) delivered via the Respimat inhaler.

Berodual® HFA pMDI: Berodual (fenoterol hydrobromide + ipratropium bromide) delivered via an HFA metered-dose inhaler.

Atrovent® HFA pMDI: Atrovent (ipratropium bromide) delivered via an HFA metered-dose inhaler.

The cartridge can be used for 60 actuations (Spiriva® Respimat®) or 120 actuations (Berodual® Respimat), sufficient for 30 days’ use with the standard daily dose of 2 actuations (Spiriva Respimat: 2 actuations = 1 dose once daily) or 4 actuations (Berodual Respimat: 1 actuation = 1 dose 4 times) a day.

Enhanced Digital Features

To view enhanced digital features for this article go to 10.6084/m9.figshare.8528534.

References

- 1.Wachtel H, Kattenbeck S, Dunne S, Disse B. The Respimat® development story: patient-centered innovation. Pulm Ther. 2017;3:19–30. doi: 10.1007/s41030-017-0040-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Forte R, Jr, Dibble C. The role of international environmental agreements in metered-dose inhaler technology changes. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1999;104:S217–S220. doi: 10.1016/S0091-6749(99)70033-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brand P, Hederer B, Austen G, Dewberry H, Meyer T. Higher lung deposition with Respimat Soft Mist inhaler than HFA–MDI in COPD patients with poor technique. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2008;3:763–770. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S3930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Fifth Assessment Report (AR5); 2014. http://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar5/. Accessed Jan 23 2019.

- 5.World Resources Institute. Greenhouse gas protocol: product life cycle accounting and reporting standard; 2011. http://www.ghgprotocol.org/product-standard. Accessed Jan 23 2019.

- 6.Environmental Resources Management. Greenhouse gas accounting sector guidance for pharmaceutical products and medical devices; 2012. https://ghgprotocol.org/sites/default/files/Summary-Document_Pharmaceutical-Product-and-Medical-Device-GHG-Accounting_November-2012_0.pdf. Accessed Jan 23 2019.

- 7.SOLVAY. SOLKANE® 227 pharma and SOLKANE® 134 pharma datasheet; 2019. https://www.solvay.us/en/binaries/35442-237443.pdf. Accessed June 12 2019.

- 8.House of Commons Environmental Audit Committee. UK progress on reducing F-gas emissions: fifth report of session 2017–19; 2018. https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201719/cmselect/cmenvaud/469/469.pdf. Accessed May 23 2019.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets obtained during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.