Abstract

Introduction

Although aspirin (ASA) is the mainstay of treatment for the prevention of recurrent ischemic stroke, the Clopidogrel versus Aspirin in Patients at Risk of Ischemic Events (CAPRIE) trial showed ASA monotherapy to be inferior to clopidogrel in preventing recurrent adverse cardiovascular outcomes in patients with high cardiac risks. Here, we aimed to systematically compare ASA versus clopidogrel monotherapy for the treatment of patients with stable coronary artery disease (CAD).

Methods

Electronic databases were searched and studies were included if they compared ASA versus clopidogrel monotherapy for the treatment of patients with CAD and they reported adverse clinical outcomes. The latest version of RevMan software (version 5.3) was used as the statistical tool for the data analysis. Odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were generated to interpret the data.

Results

A total number of 5497 patients (from years 2003 to 2011) were treated with ASA monotherapy, whereas 2544 patients were treated with clopidogrel monotherapy. Results of this analysis showed no significant difference in composite endpoints (cardiovascular death, myocardial infarction, and stroke) (OR 0.99, 95% CI 0.47–2.10; P = 0.98), all-cause mortality (OR 1.05, 95% CI 0.82–1.33; P = 0.71), cardiac death (OR 0.89, 95% CI 0.17–4.74; P = 0.89, myocardial infarction (OR 0.84, 95% CI 0.52–1.36; P = 0.48), stroke (OR 1.26, 95% CI 0.39–4.06; P = 0.70), and bleeding defined by the Bleeding Academic Research Consortium (BARC [grade 3 or above]) (OR 1.28, 95% CI 0.78–2.12; P = 0.33).

Conclusion

This analysis did not show any significant difference in all-cause mortality, cardiac death, myocardial infarction, stroke, and BARC grade 3 or above among CAD patients who were treated with either ASA or clopidogrel monotherapy. However, as a result of the limited data, this hypothesis should be confirmed in other major trials.

Keywords: Adverse clinical outcomes, Aspirin monotherapy, Cardiology, Clopidogrel monotherapy, Coronary artery disease

Introduction

Nowadays, revascularization by percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) is increasing in patients with coronary artery disease (CAD). This drastic increase might be due to several advantages of this invasive procedure compared to open-heart surgery [1]. Although dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) is often prescribed in patients with stable CAD without revascularization, this drug regimen is often indicated after implantation of drug-eluting stents (DES) to reduce and prevent stent thrombosis, re-infarction, and even stroke which might lead to severe unwanted health conditions [2]. However, as a result of other health issues, there is a small subgroup of patients who can either use aspirin (ASA) or clopidogrel monotherapy, but not both [3, 4].

Although ASA is the mainstay of treatment for the prevention of recurrent ischemic stroke [5], the Clopidogrel versus Aspirin in Patients at Risk of Ischemic Events (CAPRIE) trial showed ASA monotherapy to be inferior to clopidogrel in preventing recurrent adverse cardiovascular outcomes in patients with high cardiac risks [6].

Therefore, through this analysis, we aimed to systematically compare ASA versus clopidogrel monotherapy for the treatment of patients with stable CAD.

Methods

Databases

The following electronic databases were searched:

Cochrane Central

Excerpta Medica database (EMBASE) (www.sciencedirect.com)

Medical Literature Analysis and Retrieval System Online (MEDLINE)

Google Scholar

Search Terms

A broad search was carried out using the aforementioned online databases. The search terms included:

Aspirin versus clopidogrel monotherapy and coronary artery disease

Aspirin versus clopidogrel and percutaneous coronary intervention

Aspirin, clopidogrel, PCI

Aspirin, clopidogrel, cardiovascular disease

Aspirin monotherapy, PCI

Clopidogrel monotherapy, PCI

These terms were searched and English publications were retrieved.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Studies were included if:

They compared the treatment outcomes with ASA versus clopidogrel monotherapy in patients with CAD.

They reported the relevant adverse clinical (cardiovascular and bleeding) outcomes.

Studies were excluded if:

They were reviews, case studies, or letters to editors.

They did not compare treatment outcomes with ASA versus clopidogrel monotherapy in patients with CAD.

They compared ASA monotherapy versus DAPT in patients with CAD.

They did not report the relevant adverse clinical outcomes.

They were duplicated studies.

Outcomes Assessed and Follow-up Time Periods

The outcomes which were assessed are listed in Table 1. They included:

Composite outcomes: a combination of cardiovascular death, myocardial infarction (MI), and stroke

All-cause mortality

Cardiac death

MI

Stroke

Bleeding defined by the Bleeding Academic Research Consortium (BARC) grade 3 or above [7]

Table 1.

Outcomes which were reported

| Studies | Adverse outcomes | Follow-up period |

|---|---|---|

| Berger (2008) [11] | Death | 2 years |

| Lemesle (2016) [12] | Composite endpoints, all-cause death, cardiac death, MI, stroke, BARC type ≥ 3 bleeding | 2 years |

| Park (2016) [13] | Composite endpoints, all-cause death, cardiac death, MI, stroke, BARC type ≥ 3 bleeding | 3 years |

MI myocardial infarction, BARC bleeding according to the Bleeding Academic Research Consortium; composite outcomes include: cardiovascular death, MI and stroke

This analysis had a mean follow-up period ranging from 2 to 3 years.

Data Extraction and Quality Assessment

The following data were extracted by all three authors:

Number of participants in the ASA monotherapy group

Number of participants in the clopidogrel monotherapy group

Type of study

Adverse clinical (cardiovascular and bleeding) outcomes along with the follow-up periods

Baseline features

Patients’ enrollment time period for study

Methodological quality of the studies

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) reporting guideline was followed [8]. The methodological quality of the studies was assessed by the:

Statistical Analysis

The latest version of RevMan software (version 5.3) was used as the statistical tool for the data analysis. Odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were generated to interpret the data.

Heterogeneity was assessed by the:

Q statistical test (P ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant)

I2 statistical test (the higher the value of I2, the greater the heterogeneity)

A fixed (I2 < 50%) effects model or a random (I2 > 50%) effects model was used on the basis of the I2 values which were obtained.

Sensitivity analysis was carried out by excluding each study turn by turn, and observing any significant difference in the results which were obtained.

Publication bias was observed through funnel plots.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Results

Searched Outcomes

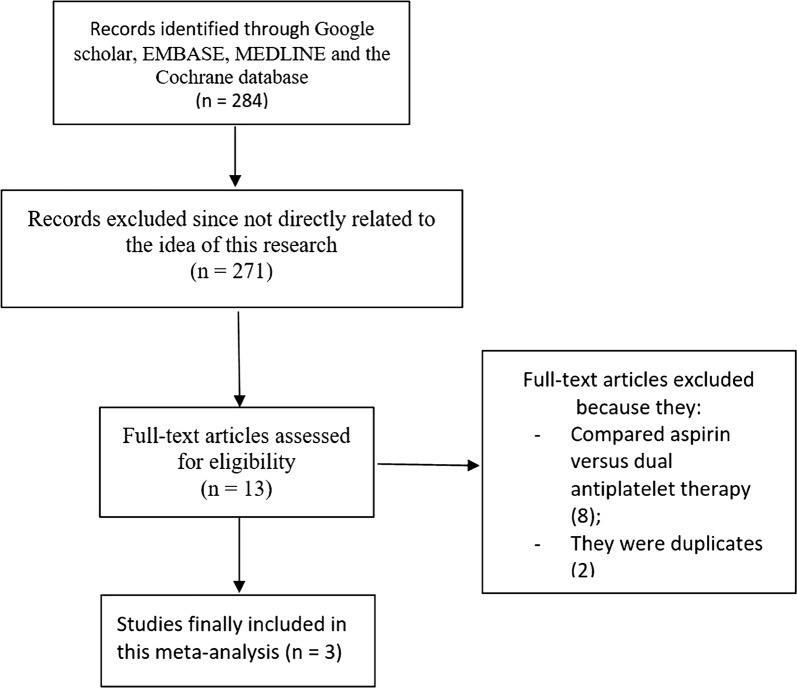

Electronic search resulted in 284 articles. After careful assessment of the abstracts, 271 articles were eliminated because they were not related to the scope of this research. Thirteen full-text articles were assessed for eligibility. Further eliminations were due to the following reasons:

They compared ASA versus DAPT (8).

They were duplicated studies (2).

Finally, only three articles [11–13] were selected for this analysis as shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram of study selection

General Features of the Studies

Two studies were observational cohorts, whereas one study was a sub-study of a randomized controlled trial. Table 2 lists the general features of the studies which were included in this analysis.

Table 2.

General features of the studies

| Studies | No. of patients treated with aspirin monotherapy (n) | No. of patients treated with clopidogrel monotherapy (n) | Year of patients’ enrollment | Type of study |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Berger (2008) [11] | 1000 | 1000 | – | RCT |

| Lemesle (2016) [12] | 2025 | 773 | 2010–2011 | OS |

| Park (2016) [13] | 2472 | 771 | 2003–2010 | OS |

| Total no. of patients (n) | 5497 | 2544 |

RCT randomized controlled trial, OS observational study

A total of 5497 patients were treated with ASA monotherapy, whereas 2544 patients were treated with clopidogrel monotherapy. Patients’ enrollment period ranged from the year 2003 to 2011 as shown in Table 2.

After careful assessment of the methodological quality of each study, a moderate risk of bias was expected with the randomized trial, whereas a low bias risk was observed in both of the observational studies.

Baseline Features of Participants

Table 3 lists the baseline features of the participants. Mean age varied from 62 to 68.2 years. Most of the participants were male patients with comorbidities such as hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes mellitus, and smoking. According to the baseline features, there were no significant differences between those patients who were treated by ASA or clopidogrel monotherapy.

Table 3.

Baseline features of the participants

| Studies | Age (years) | Men (%) | HT (%) | Ds (%) | DM (%) | Cs (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ASA/CLP | ASA/CLP | ASA/CLP | ASA/CLP | ASA/CLP | ASA/CLP | |

| Berger (2008) [11] | 62.5/62.5 | 72.0/72.0 | 51.0/52.0 | 41.0/41.0 | 20.0/20.0 | 30.0/29.0 |

| Lemesle (2016) [12] | 66.5/68.2 | 77.9/78.4 | 56.0/64.7 | – | 28.3/32.6 | 10.9/12.1 |

| Park (2016) [13] | 62.0/64.0 | 73.3/73.9 | 53.2/64.5 | 28.5/33.5 | 33.7/42.2 | 17.4/22.6 |

ASA aspirin, CLP clopidogrel, HT hypertension, Ds dyslipidemia, DM diabetes mellitus, Cs current smoking

Main Results of This Analysis

This analysis had a follow-up time period of 2–3 years and the results are listed in Table 4.

Table 4.

Results of this analysis

| Outcomes | OR with 95% CI | P value | I2 (%) | Statistical model used |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Composite endpoints | 0.99 [0.47–2.10] | 0.98 | 83 | Random effects |

| All-cause death | 1.05 [0.82–1.33] | 0.71 | 13 | Fixed effects |

| Cardiac death | 0.89 [0.17–4.74] | 0.89 | 88 | Random effects |

| Myocardial infarction | 0.84 [0.52–1.36] | 0.48 | 0 | Fixed effects |

| Stroke | 1.26 [0.39–4.06] | 0.70 | 80 | Random effects |

| BARC-defined bleeding | 1.28 [0.78–2.12] | 0.33 | 10 | Fixed effects |

OR odds ratios, CI confidence intervals, BARC bleeding defined according to the Bleeding Academic Research Consortium

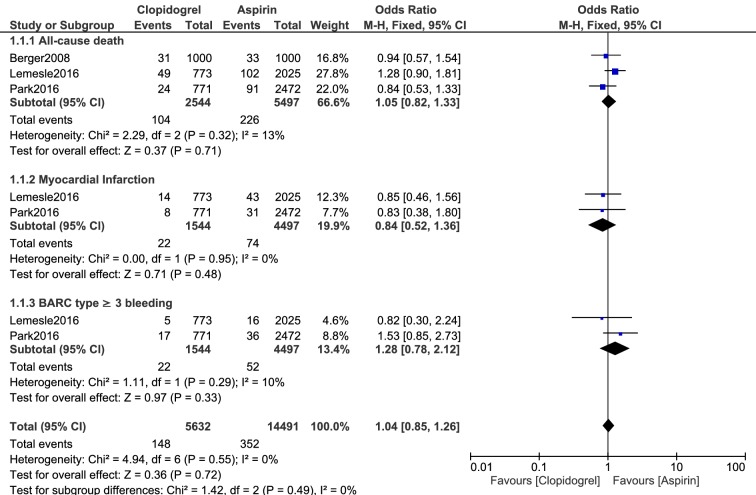

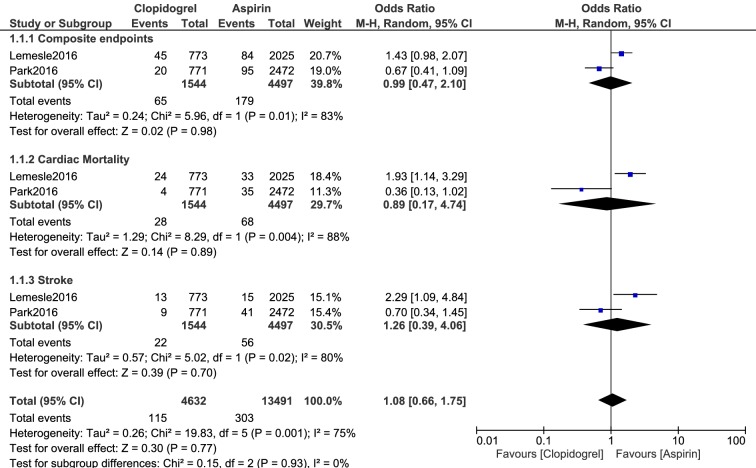

No significant difference was observed in composite endpoints (cardiovascular death, MI, and stroke) (OR 0.99, 95% CI 0.47–2.10; P = 0.98), all-cause mortality (OR 1.05, 95% CI 0.82–1.33; P = 0.71), cardiac death (OR 0.89, 95% CI 0.17–4.74; P = 0.89), MI (OR 0.84, 95% CI 0.52–1.36; P = 0.48), stroke (OR 1.26, 95% CI 0.39–4.06; P = 0.70), and BARC-defined bleeding grade 3 or above (OR 1.28, 95% CI 0.78–2.12; P = 0.33) as shown in Figs. 2 and 3.

Fig. 2.

Adverse clinical outcomes which were observed with aspirin versus clopidogrel monotherapy (part 1)

Fig. 3.

Adverse clinical outcomes which were observed with aspirin versus clopidogrel monotherapy (part 2)

Sensitivity Analysis

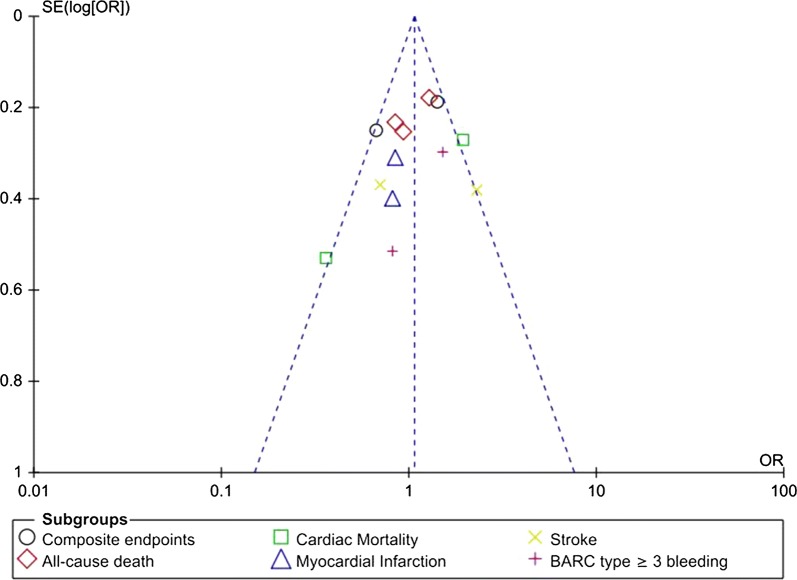

Consistent results were obtained when sensitivity analyses were carried out by eliminating each study one by one and then observing any significant difference. On the basis of a visual inspection of the funnel plot (Fig. 4), there was little to moderate evidence of publication bias across the studies which were involved in the assessment of the different clinical outcomes.

Fig. 4.

Funnel plot showing publication bias

Discussion

Guidelines recommend treatment with DAPT (aspirin + clopidogrel) following coronary angioplasty with DES. Normally, clopidogrel is used for only 6 months to 1 year, whereas aspirin is continually used throughout. However, in CAD patients with high risk of bleeding, the use of clopidogrel is a relative contraindication. Therefore, only ASA is used as a single antiplatelet agent. On the other hand, in patients with chronic gastritis, especially non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug-induced gastritis, ASA is often avoided, and therefore, those patients rely only on clopidogrel as a single antiplatelet drug.

The results of the current analysis showed no significant difference in clinical outcomes with ASA or clopidogrel monotherapy. All-cause mortality, cardiac death, MI, stroke, and bleeding defined by the Bleeding Academic Research Consortium were not significantly different. A recent meta-analysis even showed that a high dose of ASA following coronary angioplasty was not associated with significantly higher cardiovascular death/MI/stroke or any major bleeding, implying that ASA alone might be safe to use [14]. In addition, a randomized open-label Korean study involving 60 healthy participants showed ASA and clopidogrel to have similar absorption profiles implying that both treatments were equally tolerated [15].

A CAPRIE-based cost-effectiveness model for Greece investigating ASA versus clopidogrel in patients with atherosclerosis showed the latter to be cost effective as a secondary prevention of thrombotic events in Greek patients, implying that a single antiplatelet agent would also work well instead of a DAPT regimen [16].

Several studies were based on the comparison of DAPT versus antiplatelet drug therapy. In the Future REvascularization Evaluation in patients with Diabetes mellitus: Optimal management of Multivessel disease (FREEDOM) trial, the authors showed no difference in cardiovascular or bleeding outcomes with the use of either DAPT or aspirin monotherapy [17]. It should be noted that the cardiovascular outcomes included non-fatal MI, all-cause mortality, and stroke, whereas the bleeding outcomes consisted of blood transfusion, major bleeding, and hospitalization for bleeding events during a long-term period following coronary artery bypass surgery.

The Management of ATherothrombosis with Clopidogrel in High-risk patients (MATCH) trial showed that the addition of ASA to clopidogrel in high-risk patients who were recently affected by thrombotic events resulted in a higher risk of life-threatening and major bleeding, thus favoring the use of clopidogrel as the only single antiplatelet agent [18]. In addition, when the use of clopidogrel was compared to that of ASA monotherapy following 12 months DAPT use, clopidogrel monotherapy was cost effective in an analysis from a China payer’s perspective [19]. Also a recent study showed clopidogrel monotherapy to be more beneficial to smokers with atherosclerotic diseases [20].

Although the current analysis showed ASA and clopidogrel monotherapy to be equally tolerated, other larger trials should confirm this hypothesis. Furthermore, other new results will be obtained with the upcoming SMART-CHOICE trial which will assess DAPT versus clopidogrel monotherapy following PCI [21].

Finally, a limitation of this analysis was that the total number of participants was not sufficient to reach a significant conclusion. In addition, other bleeding outcomes and stent thrombosis were unfortunately not assessed because they were not reported in these studies. Finally, we should not completely depend on this new hypothesis which has been generated with limited data. Future results and conclusions generated by larger well-conducted clinical trials should be awaited.

Conclusions

This analysis did not show any significant difference in all-cause mortality, cardiac death, MI, stroke, and BARC-defined bleeding grade 3 or above among CAD patients who were treated with ASA or clopidogrel monotherapy. However, this hypothesis should be confirmed in other major trials.

Acknowledgements

Funding

No funding or sponsorship was received for this study or publication of this article.

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Author Contributions

Jun Yuan, Guang Ma Xu, and Jiawang Ding were responsible for the conception and design, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting the initial manuscript and revising it critically for important intellectual content. Jun Yuan wrote this manuscript. All the authors agreed to the final manuscript.

Disclosures

Jun Yuan, Guang Ma Xu, and Jiawang Ding have nothing to disclose.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Data Availability

All data and materials used in this research are freely available. References have been provided.

Footnotes

Enhanced Digital Features

To view enhanced digital features for this article go to 10.6084/m9.figshare.8166905.

References

- 1.Bundhun PK, Soogund MZ, Huang WQ. Same day discharge versus overnight stay in the hospital following percutaneous coronary intervention in patients with stable coronary artery disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. PLoS One. 2017;12(1):e0169807. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0169807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Levine GN, Bates ER, Blankenship JC, et al. 2011 ACCF/AHA/SCAI guideline for percutaneous coronary intervention. A report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;58(24):e44–e122. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Larsen SB, Grove EL, Neergaard-Petersen S, Würtz M, Hvas AM, Kristensen SD. Reduced antiplatelet effect of aspirin does not predict cardiovascular events in patients with stable coronary artery disease. J Am Heart Assoc. 2017;6(8):e006050. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.117.006050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bundhun PK, Teeluck AR, Bhurtu A, Huang WQ. Is the concomitant use of clopidogrel and proton pump inhibitors still associated with increased adverse cardiovascular outcomes following coronary angioplasty?: a systematic review and meta-analysis of recently published studies (2012–2016) BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2017;17(1):3. doi: 10.1186/s12872-016-0453-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Montalescot G, Sechtem U, Achenbach S, et al. 2013 ESC guidelines on the management of stable coronary artery disease: the Task Force on the management of stable coronary artery disease of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur Heart J. 2013;34(38):2949–3003. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/eht296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.CAPRIE Steering Committee A randomised, blinded, trial of clopidogrel versus aspirin in patients at risk of ischaemic events (CAPRIE) Lancet. 1996;348(9038):1329–1339. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)09457-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kikkert WJ, van Geloven N, van der Laan MH, et al. The prognostic value of Bleeding Academic Research Consortium (BARC)-defined bleeding complications in ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: a comparison with the TIMI (Thrombolysis In Myocardial Infarction), GUSTO (Global Utilization of Streptokinase and Tissue Plasminogen Activator for Occluded Coronary Arteries), and ISTH (International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis) bleeding classifications. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63(18):1866–1875. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.01.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaboration. BMJ. 2009;339:b2700. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, et al. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327:557–560. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wells GA, Shea B, O’Connell D, et al. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality if nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. http://www.ohrica/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxfordhtm. 2009. Available from http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.htm. Accessed 19 Oct 2009.

- 11.Berger K, Hessel F, Kreuzer J, Smala A, Diener HC. Clopidogrel versus aspirin in patients with atherothrombosis: CAPRIE-based calculation of cost-effectiveness for Germany. Curr Med Res Opin. 2008;24(1):267–274. doi: 10.1185/030079908X253762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lemesle G, Schurtz G, Meurice T, et al. Clopidogrel use as single antiplatelet therapy in outpatients with stable coronary artery disease: prevalence, correlates and association with prognosis (from the CORONOR Study) Cardiology. 2016;134(1):11–18. doi: 10.1159/000442706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Park TK, Song YB, Ahn J, et al. Clopidogrel versus aspirin as an antiplatelet monotherapy after 12-month dual-antiplatelet therapy in the era of drug-eluting stents. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2016;9(1):e002816. doi: 10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.115.002816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bundhun PK, Janoo G, Teeluck AR, Huang WQ. Adverse clinical outcomes associated with a low dose and a high dose of aspirin following percutaneous coronary intervention: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2016;16(1):169. doi: 10.1186/s12872-016-0347-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Choi HK, Ghim JL, Shon J, Choi YK, Jung JA. Pharmacokinetics and relative bioavailability of fixed-dose combination of clopidogrel and aspirin versus coadministration of individual formulations in healthy Korean men. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2016;25(10):3493–3499. doi: 10.2147/DDDT.S109080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kourlaba G, Fragoulakis V, Maniadakis N. Clopidogrel versus aspirin in patients with atherothrombosis: a CAPRIE-based cost-effectiveness model for Greece. Appl Health Econ Health Policy. 2012;10(5):331–342. doi: 10.1007/BF03261867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.van Diepen S, Fuster V, Verma S, et al. Dual antiplatelet therapy versus aspirin monotherapy in diabetics with multivessel disease undergoing CABG: FREEDOM Insights. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;69(2):119–127. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.10.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Diener HC, Bogousslavsky J, Brass LM, et al. Aspirin and clopidogrel compared with clopidogrel alone after recent ischaemic stroke or transient ischaemic attack in high-risk patients (MATCH): randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2004;364(9431):331–337. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16721-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang L, Lin Z, Yin H, Liu J, Xuan J. Clopidogrel versus aspirin for the treatment of acute coronary syndrome after a 12-month dual antiplatelet therapy: a cost-effectiveness analysis from China payer’s perspective. Clin Ther. 2018;40(12):2125–2137. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2018.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rollini F, Franchi F, Cho JR, et al. Cigarette smoking and antiplatelet effects of aspirin monotherapy versus clopidogrel monotherapy in patients with atherosclerotic disease: results of a prospective pharmacodynamic study. J Cardiovasc Transl Res. 2014;7(1):53–63. doi: 10.1007/s12265-013-9535-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Song YB, Oh SK, Oh JH, et al. Rationale and design of the comparison between a P2Y12 inhibitor monotherapy versus dual antiplatelet therapy in patients undergoing implantation of coronary drug-eluting stents (SMART-CHOICE): a prospective multicenter randomized trial. Am Heart J. 2018;197:77–84. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2017.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data and materials used in this research are freely available. References have been provided.