Abstract

Background

Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) is a surgical procedure performed to maintain nutrition in the short‐ or long‐term. During the procedure, a feeding tube that delivers either a liquid diet, or medication, via a clean or sterile delivery system, is placed surgically through the anterior abdominal wall. Those undergoing PEG tube placement are often vulnerable to infection because of age, compromised nutritional intake, immunosuppression, or underlying disease processes such as malignancy and diabetes mellitus. The increasing incidence of methicillin‐resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) contributes both an additional risk to the placement procedure, and to the debate surrounding antibiotic prophylaxis for PEG tube placement. The aim of surgical antimicrobial prophylaxis is to establish a bactericidal concentration of an antimicrobial drug in the patient's serum and tissues, via a brief course of an appropriate agent, by the time of PEG tube placement in order to prevent any peristomal infections that might result from the procedure.

Objectives

To establish whether prophylactic use of systemic antimicrobials reduces the risk of peristomal infection in people undergoing placement of percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy tubes.

Search methods

In August 2013, for this third update, we searched the Cochrane Wounds Group Specialised Register; The Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (The Cochrane Library); Ovid Medline; Ovid Medline (In‐Process & Other Non‐Indexed Citations); Ovid Embase; and EBSCO CINAHL.

Selection criteria

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) evaluating the use of prophylactic antimicrobials during PEG tube placement, with no restrictions regarding language of publication, date of publication, or publication status. Both review authors independently selected studies.

Data collection and analysis

Both review authors independently extracted data and assessed study quality. Meta‐analyses were performed where appropriate.

Main results

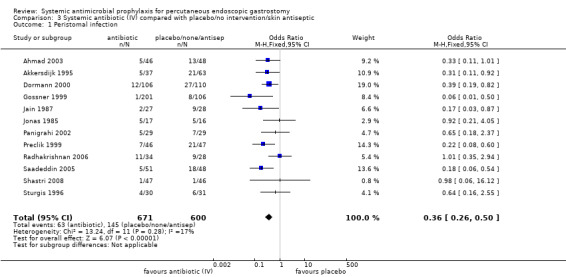

One new trial was identified and included in this update, bringing the total to 13 eligible RCTs, with a total of 1637 patients. All trials reported peristomal infection as an outcome. A pooled analysis of 12 trials resulted in a statistically significant reduction in the incidence of peristomal infection with prophylactic antibiotics (1271 patients pooled: OR 0.36, 95% CI 0.26 to 0.50). The newly identified trial compared IV antibiotics with antibiotics via PEG and could not be included in the meta‐analysis.

Authors' conclusions

Administration of systemic prophylactic antibiotics for PEG tube placement reduces peristomal infection.

Keywords: Humans, Antibiotic Prophylaxis, Anti‐Infective Agents, Anti‐Infective Agents/therapeutic use, Bacterial Infections, Bacterial Infections/prevention & control, Gastrostomy, Gastrostomy/adverse effects, Gastrostomy/methods, Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic, Risk Factors, Surgical Wound Infection, Surgical Wound Infection/etiology, Surgical Wound Infection/prevention & control

Plain language summary

Antibiotics given before the placement of a percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) tube with the aim of reducing infection at the site

Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) is a surgical procedure for inserting a feeding tube that goes into the stomach (through the abdomen) of patients who cannot take food by mouth. Antibiotics are often given intravenously before this surgical procedure, as a precaution to reduce the risk of infection at the site of operation. Thirteen research studies were included in this review, and they confirm that those people who were given antibiotics when their PEG tube was inserted were less likely to suffer an infection at the site than those who were not given antibiotics.

Background

Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) is an endoscopic technique used to surgically place a feeding tube into the stomach (Geeganage 2012). PEG tubes are used to maintain adequate nutrition in the short‐ or long‐term. PEG placement was first described over 20 years ago (Gauderer 1980), and has since become a convenient, relatively safe and simple procedure. PEG tubes can be used to deliver a liquid diet, as well as medication, via a clean, or sterile, delivery system.

PEG tube placement may be required when patients have:

an altered level of consciousness;

dysphagia (difficulty in swallowing);

tumour(s);

had a neurological event;

tracheal‐oesophageal fistula; or

chronic reflux problems.

(Tham 1997) suggested that PEG tube placement was contraindicated in patients with rapidly‐progressing, incurable disease, and in those who were likely to recover from their swallowing difficulties quickly, for example, some stroke patients. Similarly, Skelly 2002 did not recommend PEG tube placement in patients who were in a permanent vegetative state, and produced a decision‐making algorithm which stated that patients with anorexia‐cachexia syndromes should not be offered them either.

Placement of a PEG tube is usually undertaken by a doctor with the aid of an assistant (often a nurse) ‐ although the changing role of the nurse may mean that nurses could undertake this procedure at some point in the future. A choice of techniques is available. These include pushing, or pulling, through an introducer, with the pull through technique being the most widely used. The 'pull' technique involves the use of an endoscope to guide placement of the tube, which is pulled through the mouth, oesophagus, stomach and abdominal wall to the outside. The 'push' technique uses an endoscope to illuminate and insufflate the stomach in order to guide placement of the tube, then a trocar is pushed through the abdominal wall from the outside and the PEG tube is fed into the abdominal wall over a guide‐wire.

Those undergoing PEG tube placement are often vulnerable to infection for a variety of reasons including old age, compromised nutritional intake, immunosuppression and underlying disease such as malignancy and diabetes mellitus (Lee 2002). As the increase in the incidence of meticillin‐resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) poses an additional risk for the procedure, there is debate concerning the merits of antibiotic prophylaxis (Ogundipe 2004), and whether MRSA naso‐pharyngeal colonisation may be a predictor of peristomal infection in PEG tube placement by means of the pull technique (Hull 2001). Infection associated with PEG tube placement accounts for many of the minor, major and fatal complications incurred by patients with PEG tubes (Calton 1992; Nicholson 2000). Superficial surgical site infections (i.e. peristomal) caused by PEG tube placement involve skin, or subcutaneous tissue, and at least one of the following: pus; a swab with more than 106 colony forming units (cfu) per mm³ tissue; pain; localised swelling; redness and heat; as diagnosed by the attending clinician (Mangram 1999). The procedure has a mortality rate of approximately 2% (Skelly 2002).

Antimicrobial agents destroy or inhibit the multiplication of bacteria, fungi, protozoa or viruses (Perry 2002). Antimicrobial prophylaxis for surgery comprises a very brief course of an antimicrobial agent, often initiated intravenously just before the operation begins, which may continue for a set period of time post‐operatively. Delivery of the initial dose of an antimicrobial agent ensures that a prophylactic, bactericidal concentration of the drug is present in the serum and tissues by the time the skin is incised (Mangram 1999).

A systematic review and meta‐analysis of the effects of prophylactic antibiotics for PEG tube placement was published in 2000 (Sharma 2000). This review supported the use of prophylactic antibiotics for the procedure, and, currently, both national and international guidelines advocate the use of antibiotic prophylaxis (BSG 2001; Rey 1998). One US study performed a cost analysis of antibiotic prophylaxis for PEG tube placement, which was based on seven randomised controlled trials (RCTs), and found it a cost‐effective strategy in the prevention of infection (Kulling 2000).

A Cochrane systematic review on the subject was originally justified, as the review by Sharma 2000 has not been updated, and contained methodological weaknesses; specifically, it was limited to published studies, with no attempts made to retrieve unpublished work. For the updated Cochrane review (this is the third update) we undertook new searches and attempted to retrieve unpublished studies as well as any newly‐published studies. Before the first update was published in 2008, another systematic review was published that confirmed the need for prophylactic antibiotics (Jafri 2007), and calculated on the basis of numbers‐needed‐to‐treat that penicillin‐based prophylaxis was more effective than cephalosporin‐based prophylaxis.

Objectives

This review seeks to establish whether prophylactic use of systemic antimicrobial drugs reduces the risk of peristomal infection in people undergoing the placement of tubes via percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG).

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) evaluating antimicrobial prophylaxis in people undergoing placement of PEG tubes.

Types of participants

Studies in people of any age, gender or diagnosis, undergoing placement of a PEG tube (the placement of a feeding tube through the anterior abdominal wall of the stomach using an endoscopic technique). Studies in people undergoing replacement of PEG tubes were excluded, along with those undergoing percutaneous endoscopic jejunostomy (PEJ), or percutaneous endoscopic duodenostomy (PED).

Types of interventions

Studies involving antimicrobial prophylaxis compared with placebo or usual care; and comparisons between different antimicrobial regimens, were eligible for inclusion.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Diagnosis of peristomal site infection (as defined by the study authors) up to 30 days after placement of PEG tube.

Secondary outcomes

Identification of bacteria causing infection

Peritonitis

Adverse effects, such as antibiotic‐associated diarrhoea or anaphylaxis

Mortality

Removal of PEG tube because of infection

Length of hospital stay

Search methods for identification of studies

Details of the search methods used in the second update are provided in Appendix 1.

Electronic searches

In August 2013, for this third update, we searched the following databases:

Cochrane Wounds Group Specialised Register (searched 30 August 2013);

The Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (The Cochrane Library 2013, Issue 7);

Ovid MEDLINE (2011 to August Week 3 2013);

Ovid MEDLINE (In‐Process & Other Non‐Indexed Citations August 29, 2013);

Ovid EMBASE (2011 to 2013 Week 34);

EBSCO CINAHL (2011 to 29 August 2013)

The search strategies for Ovid MEDLINE, Ovid EMBASE and EBSCO CINAHL can be found in Appendix 2, Appendix 3 and Appendix 4 respectively. The Ovid MEDLINE search was combined with the Cochrane Highly Sensitive Search Strategy for identifying randomised trials in MEDLINE: sensitivity‐ and precision‐maximizing version (2008 revision); Ovid format (Lefebvre 2011). The EMBASE and CINAHL searches were combined with the trial filters developed by the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN) (SIGN 2008). The following search strategy was used in CENTRAL and adapted as appropriate for other databases: #1 MeSH descriptor: [Endoscopy, Gastrointestinal] explode all trees 3527 #2 percutaneous 7013 #3 #1 and #2 53 #4 percutaneous next endoscopic next gastrostom* 167 #5 PEG next (tube* or feed*) 47 #6 peristomal near/5 endoscop* 6 #7 #3 or #4 or #5 or #6 190 #8 MeSH descriptor: [Antibiotic Prophylaxis] explode all trees 1111 #9 antimicrobial prophylaxis 864 #10 antibiotic* near/5 (prophyla* or prevent*) 3749 #11 MeSH descriptor: [Cephalosporins] explode all trees 3654 #12 MeSH descriptor: [Amoxicillin‐Potassium Clavulanate Combination] explode all trees 450 #13 cefuroxine or ceftriaxone or co‐amoxiclav 1210 #14 #8 or #9 or #10 or #11 or #12 or #13 7690 #15 #7 and #14 31

There were no restrictions on the basis of language of publication, date of publication, or publication status.

Searching other resources

The bibliographies of all retrieved publications identified by these strategies were searched for further studies. We contacted manufacturers of the PEG tubes and experts in the field regarding the studies for inclusion. Conference abstracts were searched whilst performing the electronic search.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

The two review authors independently examined titles and abstracts, where available, of studies identified from the search, to establish whether they met the inclusion criteria. Full‐text copies of all papers that potentially met the inclusion criteria were retrieved. The two review authors independently assessed the full‐text papers against the inclusion criteria. Disagreement regarding quality, or the inclusion or exclusion of a study, was resolved through discussion. Both review authors assessed duplicate publications, and, whilst data from duplicate publications were included only once, all publications pertaining to a single study were retrieved and used to enable full data extraction and quality assessment.

Data extraction and management

The two review authors extracted data independently using a piloted data extraction form. The data that were extracted, in addition to those required for assessment of study validity, included the following.

Country in which the study was conducted.

Study eligibility criteria, including reason for PEG tube placement.

Key baseline characteristics of participants by group.

Method of PEG tube insertion.

Intervention, dosage, route, timing.

PEG catheter material.

Comparator.

Co‐interventions by group.

Rates of peristomal site infection (as defined by the study authors) up to 30 days after placement of PEG tube.

Causal bacteria, and whether the infection arose from the person's own micro‐organisms or from an external source.

Author's definition of peristomal infection.

Duration of follow‐up.

Adverse effects, such as antibiotic‐associated diarrhoea or anaphylaxis.

Mortality.

Removal of PEG tube because of infection.

Number of peristomal infections specific to the PEG clinician.

Location in health care setting.

Length of hospital stay.

Sponsorship of studies by commercial organisations.

We contacted study authors for any missing data. We resolved disagreements by discussion and referred to the Cochrane Wounds Group editorial base when necessary.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Both review authors independently assessed each included study using the Cochrane Collaboration tool for assessing risk of bias (Higgins 2011). This tool addresses six specific domains, namely sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding, incomplete outcome data, selective outcome reporting and other issues (e.g. extreme baseline imbalance)(see Appendix 5 for details of criteria on which the judgement will be based). Blinding and completeness of outcome data were assessed for each outcome separately. We completed a risk of bias table for each eligible study. We discussed any disagreement between both review authors to achieve a consensus.

We presented assessment of risk of bias using a 'risk of bias summary figure', which presents all of the judgements in a cross‐tabulation of study by entry. This display of internal validity indicates the weight the reader may give the results of each study.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We explored both clinical and statistical heterogeneity. Where it was appropriate to pool studies, in the absence of clinical and statistical heterogeneity, we applied a fixed‐effect model to pool data. We assessed heterogeneity between study results using the I2 statistic (Higgins 2003). This examines the percentage total variation across studies due to heterogeneity rather than to chance. Values of I2 over 75% indicate a high level of heterogeneity. In instances where statistical synthesis would have been clinically inappropriate, we undertook a narrative overview.

Data synthesis

We entered the outcome data into RevMan 5.2 software. We presented results with 95% confidence intervals (CI); also, as the event rate was less than 30%, we reported estimates for dichotomous outcomes (for example, presence or absence of PEG placement infections) as odds ratios (OR) (Deeks 1996). We were unable to calculate the means and standard deviations of continuous data (for example, time to progression of peristomal infection). Decisions about the methods used for synthesising studies were based on the nature of the data (in terms of validity, similarity of study designs and statistical heterogeneity).

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

The data allowed us to perform the following preplanned subgroup analyses that assessed:

the impact of study validity on outcomes (i.e. adequate allocation concealment compared with inadequate allocation concealment);

the use of different antimicrobials (cephalosporins compared with penicillins); and,

commercial sponsorship of trials.

We were unable to perform other preplanned subgroup analyses to investigate specific patient groups (neonate, child, adult); different diagnostic groups (paediatric, head and neck cancer); or PEG tube placement techniques (push versus pull methods).

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

The search strategy for the review and updates resulted in 13 trials (including 1637 participants) meeting the inclusion criteria for the review (Ahmad 2003; Akkersdijk 1995;Blomberg 2010Dormann 2000; Gossner 1999; Jain 1987; Jonas 1985; Panigrahi 2002; Preclik 1999; Radhakrishnan 2006; Saadeddin 2005; Shastri 2008; Sturgis 1996). Three trials had multiple citations containing some of the same data (Dormann 2000; Gossner 1999; Preclik 1999). One new study was assessed and included for this update following full text retrieval (Blomberg 2010).

Of the 17 studies that were excluded from the review, nine were not RCTs (Adachi 2002; Arrowsmith 1997; Chowdhury 1996; Dormann 2004; Gopal 2004; Hull 2001; Lee 2002; Loser 2000; Rey 1998), one was a critique of two trials (Beales 2003), one examined PEG tube feeding and not placement (Kanie 2000), one was an abstract only (with no further detail on the study available) (Gawenda 1997) two were systematic reviews (Jafri 2007; Sharma 2000) and in three studies all patients were prescribed antibiotics (Horiuchi 2006; Maetani 2003; Maetani 2005). All studies are listed in the Characteristics of excluded studies table with reasons for their exclusion.

Included studies

Participants

Thirteen trials involved adults aged 16 years or over. All trials were published and were conducted between 1985 and 2010. Six trials by Dormann were retrieved and five were found to include similar data. Following personal correspondence, Dormann 2000 was identified as the primary study report, when confirmed by the author as being the largest and latest study. Of the 13 included trials, 12 involved both males and females, while one comprised men only (Jonas 1985). Trial sizes ranged from 37 patients (Jonas 1985), to 347 patients (Gossner 1999). The trials included hospitalised and nursing‐home patients referred for PEG tube placement, mainly for malignancy or neurological reasons that caused dysphagia. All trials took place in industrial countries, namely Germany (four trials), USA (three trials), Netherlands (one trial), Sweden (one trial) and the UK (four trials).

Antibiotics

Eleven trials compared antibiotics with a placebo, or no intervention. One trial compared intravenous antibiotics with antibiotics deposited into the PEG catheter (Blomberg 2010). One trial had three groups comparing antibiotics alone with antimicrobial skin antiseptic alone (povidone‐iodine spray) and with skin antiseptic plus antibiotics (Radhakrishnan 2006). Eight trials used a cephalosporin such as cefuroxime (Ahmad 2003; Blomberg 2010; Radhakrishnan 2006), ceftriaxone (Dormann 2000; Shastri 2008), cefazolin (Jain 1987; Sturgis 1996), or cefoxitin (Jonas 1985). Three trials used penicillin co‐amoxiclav/augmentin (Akkersdijk 1995; Panigrahi 2002; Preclik 1999). In one trial, patients were randomised into groups that received penicillin (piperacillin with tazobactam), or cephalosporin (cefotaxime), or no antibiotic (Gossner 1999). One trial compared co‐trimoxazole with cefuroxime (Blomberg 2010). In one study, patients were given co‐amoxiclav, or cephalosporin (cefotaxime) if they were allergic to penicillin (Saadeddin 2005).

In all trials but one antibiotics were administered intravenously (IV) either by bolus (Ahmad 2003; Akkersdijk 1995; Dormann 2000; Jain 1987; Jonas 1985; Panigrahi 2002; Radhakrishnan 2006; Saadeddin 2005; Shastri 2008; Sturgis 1996), or infusion (Gossner 1999; Preclik 1999). In one trial antibiotics were administered into the PEG catheter (Blomberg 2010). All but two trials (Akkersdijk 1995; Sturgis 1996), stated exclusion criteria for patients in relation to antimicrobial hypersensitivity.

Diagnostic groups

All trials gave information on patient diagnosis that comprised three major groups; malignancy, neurological conditions and miscellaneous other conditions. One trial excluded patients with malignancy (Saadeddin 2005), and in another, separate data could not be extracted from the neurological and miscellaneous group (Sturgis 1996). In the remaining eleven trials, there were a total of 460 patients with malignancy; 473 with neurological conditions, and 75 miscellaneous. In all but five trials (Akkersdijk 1995; Blomberg 2010; Dormann 2000; Preclik 1999; Radhakrishnan 2006), a greater number of patients with malignancy underwent PEG. Four trials gave details on infection rates for the diagnostic groups but further analysis of these data was not possible due to lack of detail (Dormann 2000; Jonas 1985; Preclik 1999; Sturgis 1996). Two trials did not include ambulatory patients, thus more dependent patients may have increased the proportion of infections detected (Ahmad 2003; Preclik 1999).

Outcome measures

Peristomal infection was the primary outcome in all trials. All trials used explicit criteria for assessment of peristomal infection. A wide range of other outcomes were identified by some authors, such as adverse effects of PEG, mortality, gastric pH, high levels of C reactive protein, white blood cell count, cost of antibiotic prophylaxis, major complications, post intervention antibiotic therapy, the role of oropharyngeal flora, and comparison between 'push' and 'pull' techniques (Akkersdijk 1995), however, measurements were individual to each study.

Criteria for peristomal infection

Eight trials used either the criteria devised by Jain 1987 (Ahmad 2003; Jain 1987; Radhakrishnan 2006; Saadeddin 2005), or a modified version of them (Dormann 2000; Gossner 1999; Preclik 1999; Sturgis 1996). One study (Panigrahi 2002), used the ASEPSIS criteria (see Wilson 1995), while another (Shastri 2008) used the criteria devised by Jain 1987 and Gossner 1999 (Shastri 2008). Three trials stated specific criteria for diagnosis of peristomal infection; these included redness, purulent discharge and the need for antibiotics based on judgement of physician (Akkersdijk 1995), or a red zone around the catheter, occurrence of pus, subcutaneous swelling and pain on palpation around the catheter, positive bacterial culture, high levels of C reactive protein and a high white blood cell count (Blomberg 2010), or redness, tenderness, induration, pus, local fever, and systemic leukocytosis (Jonas 1985). The number of criteria and the way in which scores were calculated differed between trials.

Length of follow‐up

The length of follow‐up for PEG patients ranged from three to 30 days. Timing of peristomal wound infection assessment varied between trials. Ahmad 2003 assessed the wound immediately and on days three, five and seven; Radhakrishnan 2006 on days three or four and seven; Dormann 2000 on days one, two, four and 10; Preclik 1999 on days one, four, seven and 30; Blomberg 2010 at follow up on days 7 to14; and Akkersdijk 1995 twice weekly for one month. Most of the other trials followed patients up daily for seven days (Gossner 1999; Jain 1987; Saadeddin 2005; Shastri 2008; Sturgis 1996), or daily for seven days and again on day 28 (Panigrahi 2002). Follow‐up for one study was unclear, but was up to day three or more (Jonas 1985).

Sample size calculations

Six trials gave no details of sample size calculations. Ahmad 2003 and Saadeddin 2005 based their trials on a group size of 45; the Shastri 2008 trial was based on 46 for a significance of P = 0.05 and a power of 80%; while Jain 1987 used 50 for a significance level of P = 0.05 and a power of 80%. The Dormann 2000 study was based on a minimum group size of 100 at a significance level of P = 0.05, but no power was stated. Four trials based their power calculations on an infection rate of 30% to 35% in the control group reducing to between 7% and 5 % with prophylaxis (Ahmad 2003; Dormann 2000; Jain 1987; Saadeddin 2005). In the trial by Preclik 1999, a sample size of 180 patients was calculated to detect a reduction in peristomal and other infections from 20% to 5% in the antibiotic group. An interim calculation was performed part way through because the reduction in infection had been achieved, and the study was prematurely terminated with 106 patients in two groups. Blomberg 2010 calculated the need for 89 or 112 patients to establish non‐inferiority at 80% power and significance level of 5% assuming infection rates of 15 or 20% in both groups respectively.

Sources of funding

One study was sponsored by a pharmaceutical company (Preclik 1999), and one of the study authors (K Madchka) was employed by the pharmaceutical company that manufactured the antibiotic used in the trial. Another study included data from an ongoing study funded by a pharmaceutical company (Dormann 2000) but it is unclear if this introduced bias. Eight trials did not report any sponsorship, and two trials reported 'no grants received' (Radhakrishnan 2006) and 'no disclosures' (Shastri 2008). One trial received funding from a cancer society and a government body and the authors declared no competing interests (Blomberg 2010).

Risk of bias in included studies

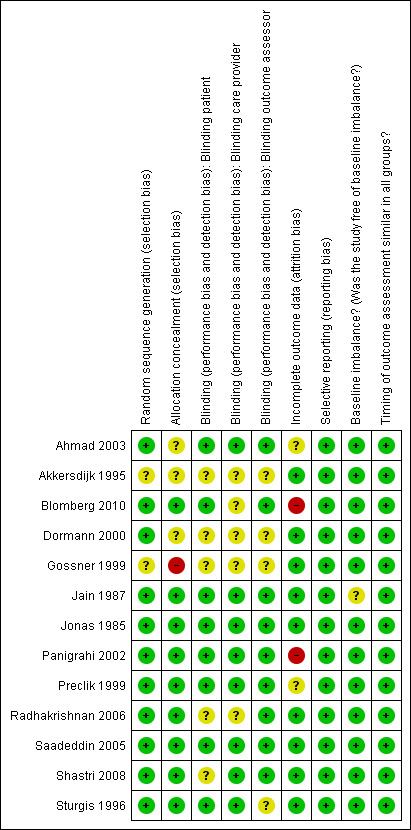

See Figure 1 for the risk of bias graph showing the review authors' judgements about each risk of bias domain as percentages across all studies. See also Figure 2 for the risk of bias summary.

1.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

2.

Methodological quality summary: review authors' judgements about each methodological quality item for each included study.

Allocation

Generation of the randomisation sequence

Four trials used block randomisation; two randomisation sequences were computer‐generated (Dormann 2000; Shastri 2008), a third trial reports a pre prepared block (Blomberg 2010), the fourth trial provided no details about the generation method of the block randomisation (Preclik 1999). Methods of randomisation were not stated in two trials (Akkersdijk 1995; Gossner 1999). Three trials used the pharmacy department to generate allocation of patients (Jonas 1985; Panigrahi 2002; Sturgis 1996); three used a computer (Ahmad 2003; Dormann 2000; Saadeddin 2005); one used a pocket calculator (Jonas 1985); and one used closed, shuffled envelopes opened at random (Radhakrishnan 2006). Overall, there was a low risk of bias for random sequence generation.

Allocation concealment

One trial provided inadequate allocation concealment methods (Gossner 1999). In three trials allocation concealment was unclear (Ahmad 2003; Akkersdijk 1995; Dormann 2000). The remaining nine trials were judged to have adequate allocation concealment (Blomberg 2010; Jain 1987; Jonas 1985; Panigrahi 2002; Preclik 1999; Radhakrishnan 2006; Saadeddin 2005; Shastri 2008; Sturgis 1996). In one trial allocation concealment was performed by one of the authors who was responsible for (and the only one aware of) assignment (Jain 1987), who did not evaluate the wounds.

Blinding

Three trials were not blinded (Akkersdijk 1995; Dormann 2000; Gossner 1999). In one trial the researcher was blinded to the allocation (Radhakrishnan 2006). In seven placebo controlled trials both the patients and care provider delivering the intervention were blinded(Ahmad 2003; Jain 1987; Jonas 1985; Panigrahi 2002; Preclik 1999; Saadeddin 2005; Sturgis 1996). In seven trials the outcome assessors were blinded (Ahmad 2003; Jain 1987; Jonas 1985; Panigrahi 2002; Preclik 1999; Radhakrishnan 2006; Saadeddin 2005). In one trial the patients and the outcome assessor were blinded (Blomberg 2010) and in another trial both the care provider and outcome assessor were blinded (Shastri 2008).

Incomplete outcome data

Drop outs / withdrawals from the study / Intention‐to‐treat analysis

Two studies reported no drop outs (Jain 1987; Sturgis 1996) and all the remaining studies reported drop outs or withdrawals from the study. Three studies stated that they had performed an intention‐to‐treat (ITT) analysis. In one study an ITT and a per‐protocol analysis was performed (Blomberg 2010). ITT analysis was not stated in two studies but as there were no drop outs and the analysis was completed on the complete data set an ITT analysis was assumed (Jain 1987; Sturgis 1996). The remaining studies reported dropouts/withdrawals, but did not report whether or not an ITT analysis had been undertaken.

Selective reporting

We did not have access to any of the trial protocols, however all the included studies reported on the pre‐specified outcomes in the methods sections of the paper.

Other potential sources of bias

Baseline comparability

All trials comprised adults aged 16 years and above; all patients had co‐morbidity that made their vulnerability to peristomal infection comparable. The participants shared similar indications for PEG tube placement and epidemiological baseline characteristics in nine of the 13 trials. In two trials the number of participants in each group differed slightly in the reasons for PEG tube insertion but this was not judged to have introduced serious bias (Jain 1987; Jonas 1985). In three trials there were slight differences in gender distribution between the antibiotic and placebo groups (Blomberg 2010; Gossner 1999; Panigrahi 2002). None of the baseline differences were judged to be at a level where they were likely to affect the outcomes or introduce serious bias.

Timing of outcome assessment

All studies reported on when the outcome assessments were made and they were judged to be similar for all arms of the trial.

Effects of interventions

Thirteen trials met the inclusion criteria for the review; no unpublished trials were identified and five authors responded to requests for information (Dormann 2000; Gossner 1999; Radhakrishnan 2006; Saadeddin 2005; Shastri 2008).

Meta‐analysis was performed where possible using a fixed‐effect model. The number of PEG infections was calculated from the last date of follow‐up in each study to ensure the maximal number of peristomal infections. Continuous data of infection rates were available in nine trials (Ahmad 2003; Dormann 2000; Jain 1987; Jonas 1985; Panigrahi 2002; Preclik 1999; Radhakrishnan 2006; Shastri 2008; Sturgis 1996), but only two studies included means and this prevented further analysis. In three trials (Akkersdijk 1995; Blomberg 2010; Radhakrishnan 2006) an ITT analysis was possible, otherwise we used available case data.

Peristomal infection

All trials recorded the incidence of peristomal infection as an outcome, and stated criteria for wound infection. In addition, all but one used intravenous antibiotics which were given prior to PEG, including two by infusion (Gossner 1999; Preclik 1999). In the remaining trial antibiotics were given intravenously and via the PEG catheter (Blomberg 2010). This trial gave antibiotics before insertion and immediately after insertion respectively.Ten trials administered the antibiotics around 30 minutes before, and two trials immediately prior to PEG tube placement (Radhakrishnan 2006; Saadeddin 2005). Two trials also gave two further doses at six‐hourly intervals (Akkersdijk 1995; Jonas 1985), and one trial gave two further doses at eight‐hourly intervals following PEG tube placement (Radhakrishnan 2006).

Systemic antibiotics (IV) compared with placebo

Eight trials with 586 participants were included in this comparison and all used saline as the placebo (Ahmad 2003; Jain 1987; Jonas 1985; Panigrahi 2002; Preclik 1999; Saadeddin 2005; Shastri 2008; Sturgis 1996). There were a total of 34/293 (11.6%) peristomal infections in the antibiotics groups, and 80/293 (27.3%) in the placebo groups. Trials were pooled using a fixed‐effect model (I2 = 0%), and statistically there were significantly fewer infections in people treated with antibiotics than with placebo (OR 0.34, 95% CI 0.22 to 0.53) (Analysis 1.1).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Systemic antibiotic (IV) compared with placebo, Outcome 1 Peristomal infection.

Systemic antibiotics (IV) compared with no intervention

Three trials with 613 participants were included in this comparison (Akkersdijk 1995; Dormann 2000; Gossner 1999). There was a total of 18/344 (5.2%) peristomal infections in the antibiotic groups, and 56/279 (20%) in the no intervention groups. Trials were pooled using a fixed‐effect model (I2 = 27%), and statistically there were significantly fewer infections in people treated with antibiotics than in those who had received no intervention (OR 0.30, 95% CI 0.17 to 0.53) (Analysis 2.1).

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Systemic antibiotic (IV) compared with no intervention, Outcome 1 Peristomal infection.

Systemic antibiotics (IV) compared with placebo or no intervention or skin antiseptic

The total number of patients included in the meta‐analysis was 1271 (n = 671 antibiotics (52.8%); n = 600 comparison groups (47.2%)). All 12 trials with 1271 participants that compared systemic antibiotics with placebo, or no intervention, or skin antiseptic, were pooled using a fixed‐effect model (I2 = 17%). Overall, 63/671 (9.4%) people in the antibiotics group, and 145/600 (24.2%) people in the placebo/no intervention/skin antiseptic groups acquired a peristomal infection. Statistically, there were significantly fewer infections in people treated with antibiotics compared with those who received placebo, or no intervention, or skin antiseptic (OR 0.36, 95% CI 0.26 to 0.50) (Analysis 3.1).

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Systemic antibiotic (IV) compared with placebo/no intervention/skin antiseptic, Outcome 1 Peristomal infection.

The finding was robust to exclusion of studies with inadequate allocation concealment. Eight trials with adequate allocation concealment were pooled using the fixed‐effect model (I2 = 61%) and this difference was statistically significant (OR 0.58, 95% CI 0.38 to 0.88), although if a random effects model is used this difference disappears (Analysis 3.2.1). The four trials with unclear or inadequate allocation concealment were pooled using the fixed‐effect model (I2 = 25%) (OR 0.34, 95% CI 0.21 to 0.58) (Analysis 3.2.2).

3.2. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Systemic antibiotic (IV) compared with placebo/no intervention/skin antiseptic, Outcome 2 Allocation concealment.

A subgroup analysis was also performed on the two trials sponsored by the pharmaceutical firms manufacturing the antibiotics administered to determine whether results were different from un sponsored trials). Pooled analyses of trials that were not sponsored (I2 = 25%) (OR 0.38, 95% CI 0.25 to 0.56) (Analysis 3.3) and sponsored trials (I2 = 0%) (OR 0.32, 95% CI 0.18 to 0.58) were consistent, in that both demonstrated a statistically significant benefit associated with antibiotics;.

3.3. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Systemic antibiotic (IV) compared with placebo/no intervention/skin antiseptic, Outcome 3 Sponsorship.

Sub‐group analyses could not be performed on specific diagnostic groups, or the use of different antibiotics, due to lack of data.

Systemic antibiotic compared with another systemic antibiotic

Two trials compared systemic antibiotics with systemic antibiotics. Gossner 1999 randomised participants between two different antibiotics given intravenously (OR 0.33, 95% CI 0.01 to 8.12) (Analysis 4.1). Blomberg 2010 randomised participants between two different antibiotics one given via PEG catheter and the other intravenously (OR 0.70, 95% CI 0.30 to 1.65) (Analysis 4.2). No difference in infection rates between the two groups could be determined in either trial.

4.1. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Systemic antibiotic compared with systemic antibiotic, Outcome 1 Systemic antibiotic (IV) compared with systemic antibiotic (IV).

4.2. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Systemic antibiotic compared with systemic antibiotic, Outcome 2 Systemic antibiotic (PEG) compared with systemic antibiotic (IV).

Systemic antibiotic (IV) compared with systemic antibiotic (IV) plus skin antiseptic

One trial with two groups of 68 participants was included in this comparison of systemic antibiotic with systemic antibiotic plus skin antiseptic (Radhakrishnan 2006). There were 11/34 (32.4%) infections in the antibiotic group and 1/34 (2.9%) in the systemic antibiotic plus skin antiseptic group, and there were statistically fewer infections when the systemic antibiotic was combined with a skin antiseptic (OR 15.78, 95% CI 1.90 to 130.86) (Analysis 5.1).

5.1. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Systemic antibiotic (IV) compared with systemic antibiotic (IV) and skin antiseptic, Outcome 1 Peristomal infection.

Skin antiseptic compared with systemic antibiotic (IV) plus skin antiseptic

One trial with two groups of 62 participants was included in this comparison of skin antiseptic with systemic antibiotic plus skin antiseptic (Radhakrishnan 2006). There were 9/28 (32.1%) infections in the skin antiseptic group and 1/34 (2.9%) in the antibiotic plus skin antiseptic group; there were statistically fewer infections when the skin antiseptic was combined with an antibiotic (OR 15.63 95% CI 1.84 to 133.09) (Analysis 6.1).

6.1. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Skin antiseptic compared with systemic antibiotic (IV) and skin antiseptic, Outcome 1 Peristomal infection.

Identification of bacteria causing infection

None of the trials reported on the causal organisms between groups.

Peritonitis

Five trials reported peritonitis as an outcome (Akkersdijk 1995; Dormann 2000; Gossner 1999; Radhakrishnan 2006; Shastri 2008).

Adverse effects associated with systemic antibiotics

Five trials did not mention any adverse effects associated with antibiotics and PEG tube placement (Jain 1987; Jonas 1985; Panigrahi 2002; Saadeddin 2005; Sturgis 1996). Six trials reported adverse effects associated with PEG tube placement but these were not antibiotic‐specific (Akkersdijk 1995; Blomberg 2010; Dormann 2000; Gossner 1999; Radhakrishnan 2006; Shastri 2008). Two trials reported adverse effects associated with antibiotics; Ahmad 2003 found that 6% of those who received antibiotics developed Clostridium difficile‐related diarrhoea, while none of the 51 patients in the placebo group developed this problem. In Preclik 1999, adverse effects occurred in two patients in the antibiotics group (nausea, seizure), and two patients in the placebo group (vomiting and allergic exanthema).

Mortality associated with systemic antibiotics

Two trials did not report any mortality figures (Jain 1987; Jonas 1985). One trial reported that there was no mortality (Gossner 1999). Ten trials reported mortality but deaths were stated as not associated with antibiotics (Ahmad 2003; Akkersdijk 1995; Blomberg 2010; Dormann 2000; Panigrahi 2002; Preclik 1999; Radhakrishnan 2006; Saadeddin 2005; Shastri 2008; Sturgis 1996).

Removal of PEG tube because of infection

One trial reported a single reinsertion of a PEG tube because of leakage that led to peritonitis (Preclik 1999). Four patients in one trial (Gossner 1999),and one patient in another (Dormann 2000) required PEG tube removal because of local peritonitis. We could not determine which treatment group these patients had been in for either trial.

Care of the peristomal site after PEG tube placement was described in seven trials, all of which used dry dressing without topical products (Ahmad 2003; Dormann 2000; Gossner 1999; Jain 1987; Preclik 1999; Saadeddin 2005; Sturgis 1996). One trial stated that all participants were given an information folder on how to perform daily care of the catheter and wound site (Blomberg 2010). Two trials stated that hydrogen peroxide was used to cleanse the PEG site (Jain 1987; Sturgis 1996).

Length of hospital stay as an indicator of increased costs

None of the trials compared length of hospital stay between groups.

Discussion

The results of this review support the use of systemic antibiotics and show that broad spectrum antibiotics are effective against peristomal infection in PEG tube placement. This supports current UK, European and USA guidelines (BSG 2001; Locke 2000; Rey 1998), and two previous systematic reviews (Jafri 2007; Sharma 2000).

The included trials were of a reasonable quality, and, although based on relatively small numbers, power calculations (where performed) suggested adequate sample sizes had been used (Ahmad 2003; Blomberg 2010; Dormann 2000; Jain 1987; Preclik 1999). The trials with inadequate allocation concealment showed fewer infections in the antibiotic groups than the trials with adequate allocation concealment.

The push method was used in at least two studies. Shastri 2008 used the push method alone, Akkersdijk 1995 compared push and pull methods and one study did not specify the method (Sturgis 1996). It is possible that pushing the PEG device through the abdominal wall, rather than pulling it though the nasopharynx and gastrointestinal tract, could avoid the risk of contamination by naso‐pharyngeal organisms including MRSA. This route may therefore negate the need for systemic prophylactic antibiotics. Further robust studies using the push method are needed to establish the evidence base.

Pooled analysis of twelve trials included in the review, comparing antibiotics with antibiotics or placebo or no intervention or skin antiseptic, showed a consistently beneficial effect for antibiotics. In one trial antibiotics plus a skin antiseptic were employed with more favourable results than antibiotic alone (Radhakrishnan 2006), however, this finding should be interpreted with caution because of the small numbers involved.

Follow‐up was insufficient in some trials (3‐30 days) which may have reduced the statistical power of the studies, particularly in the light of the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's (CDC) recommendation for a 30‐day follow‐up period to ensure that all surgical site infections are captured (Mangram 1999). Blinding in two trials may have been compromised, as PEG delivery of antibiotics (Blomberg 2010) and the use of the skin antiseptic could not be disguised (Radhakrishnan 2006).

Broad‐spectrum bactericidal antibiotics were used in all the trials reviewed. The type of antibiotics used depended on the origin of the study, as the recommendations given by UK, European and USA societies of gastroenterology cited different evidence available at the times of publication. Much of the current guidance is based on the trials included in this review. For example, one German study (Gossner 1999) used piperacillin and tazobactam in comparison with cefotaxime. Both these drugs are recommended as part of the European Society guidance (Rey 1998). One systematic review found that only six patients needed to be treated to prevent one peristomal infection when penicillin‐based antibiotics were administered, compared to 10 patients for cephalosporin‐based antibiotics (Jafri 2007).

There were prescribing differences between trials with regard to method of delivery, dose, and timing of antibiotics. The method of delivery was intravenous, by bolus or infusion, or by bolus via PEG catheter in all trials. Intravenous delivery is the UK standard for systemic antibiotic prophylaxis (BMA and RPS 2004). The dose of antibiotics given for prophylaxis was generally in accordance with routine formulary prescribing guidance for each drug used. Timing and length of administration of the systemic antibiotics varied between trials. The aim of antibiotics is to establish a bactericidal concentration in the tissues prior to PEG tube placement. This may have been compromised in the trials in which administration was not completed until immediately before PEG tube placement.

In summary, prophylactic antibiotics in PEG tube placement using the 'pull' method result in a statistically significant reduction in the number of peristomal infections.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

Prophylactic antibiotics should be routinely administered to people undergoing PEG tube insertion using the 'pull' method, since they are associated with a significant reduction in peristomal infections.

Implications for research.

No further research is needed to answer this question using the pull method. However, the 'push' method is becoming a more popular technique with limited evidence of effectiveness. A robust randomised controlled trial with sufficient power is recommended to compare the need for antibiotics using the push and pull methods. A research study comparing the use of antiseptics with and without antibiotics is recommended as there is some evidence to suggest that antiseptics combined with antibiotics may be more effective than antibiotics alone.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 30 August 2013 | New citation required but conclusions have not changed | New search, no change to conclusions. |

| 30 August 2013 | New search has been performed | Third update, one additional trial included (Blomberg 2010). |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 1, 2006 Review first published: Issue 4, 2006

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 16 February 2011 | New search has been performed | Second update, new searches one trial added (Shastri 2008), risk of bias assessment completed, no change to conclusions |

| 11 November 2008 | Amended | Contact details updated |

| 8 May 2008 | New search has been performed | First update, one new trial added (Radhakrishnan 2006), conclusions remain unchanged. |

| 2 May 2008 | Amended | Converted to new review format. |

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank their employer, the University of Glamorgan, for allowing them the time and resources to undertake the review. The authors would like to thank the following referees for their comments on the review: Cochrane Wounds Group Editors (Michelle Briggs, Nicky Cullum, Gill Cranny, David Margolis); Referees (Zoe Hodges, Ernst Kuipers, David Leaper, Caroline Main, Barbara Postle) and Copy Editor, Elizabeth Royle.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Search methods used in the second review update (2011)

Electronic searches

For this second update, we searched the following databases:

Cochrane Wounds Group Specialised Register (searched 16 February 2011);

The Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (The Cochrane Library 2011, Issue 1);

Ovid MEDLINE (1950 to February Week 1 2011);

Ovid MEDLINE (In‐Process & Other Non‐Indexed Citations February 15, 2011);

Ovid EMBASE (1980 to 2011 Week 06);

EBSCO CINAHL (1982 to 11 February 2011)

The search strategies for Ovid MEDLINE, Ovid EMBASE and EBSCO CINAHL can be found in Appendix 3, Appendix 4 and Appendix 5 respectively. The Ovid MEDLINE search was combined with the Cochrane Highly Sensitive Search Strategy for identifying randomised trials in MEDLINE: sensitivity‐ and precision‐maximizing version (2008 revision); Ovid format. The EMBASE and CINAHL searches were combined with the trial filters developed by the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN). The following search strategy was used in CENTRAL and adapted as appropriate for other databases: 1 MeSH descriptor Endoscopy, Gastrointestinal explode all trees 2 percutaneous 3 (#1 AND #2) 4 percutaneous NEXT endoscopic NEXT gastrostom* 5 PEG NEXT (tube* or feed*) 6 peristomal NEAR/5 endoscop* 7 (#3 OR #4 OR #5 OR #6) 8 MeSH descriptor Antibiotic Prophylaxis explode all trees 9 antimicrobial prophylaxis 10 antibiotic* NEAR/5 (prophyla* or prevent*) 11 MeSH descriptor Cephalosporins explode all trees 12 MeSH descriptor Amoxicillin‐Potassium Clavulanate Combination explode all trees 13 cefuroxine or ceftriaxone or co‐amoxiclav 14 (#8 OR #9 OR #10 OR #11 OR #12 OR #13) 15 (#7 AND #14)

There were no restrictions on the basis of language of publication, date of publication, or publication status.

Searching other resources

We searched the bibliographies of all retrieved and relevant publications identified by these strategies for further studies.

Appendix 2. Ovid MEDLINE search strategy

1 exp Endoscopy, Gastrointestinal/ 2 percutaneous.tw. 3 and/1‐2 4 percutaneous endoscopic gastrostom$.tw. 5 (PEG adj (tube* or feed*)).tw. 6 (peristomal adj5 endoscop*).tw. 7 or/3‐6 8 exp Antibiotic Prophylaxis/ 9 antimicrobial prophylaxis.tw. 10 (antibiotic* adj5 (prophyla* or prevent*)).tw. 11 exp Cephalosporins/ 12 exp Amoxicillin‐Potassium Clavulanate Combination/ 13 (cefuroxine or ceftriaxone or co‐amoxiclav).tw. 14 or/8‐13 15 7 and 14

Appendix 3. Ovid EMBASE search strategy

1 exp Percutaneous Endoscopic Gastrostomy/ 2 (PEG adj (tube$ or feed$)).ti,ab. 3 (peristomal adj5 endoscop$).ti,ab. 4 or/1‐3 5 exp Antibiotic Prophylaxis/ 6 antimicrobial prophylaxis.ti,ab. 7 (antibiotic$ adj5 (prophyla$ or prevent$)).ti,ab. 8 exp Cephalosporin Derivative/ 9 exp Amoxicillin Plus Clavulanic Acid/ 10 (cefuroxine or ceftriaxone or co‐amoxiclav).ti,ab. 11 or/5‐10 12 4 and 11

Appendix 4. EBSCO CINAHL search strategy

S15 S7 and S14 S14 S8 or S9 or S10 or S11 or S12 or S13 S13 TI ( cefuroxine or ceftriaxone or co‐amoxiclav ) or AB ( cefuroxine or ceftriaxone or co‐amoxiclav ) S12 (MH "Amoxicillin") S11 (MH "Cephalosporins+") S10 TI ( antibiotic* N5 prophylaxis or antibiotic* N5 prevent* ) or AB ( antibiotic* N5 prophylaxis or antibiotic* N5 prevent* ) S9TI antimicrobial prophylaxis or AB antimicrobial prophylaxis S8 (MH "Antibiotic Prophylaxis") S7 S3 or S4 or S5 or S6 S6 TI peristom* N3 endoscop* or AB peristom* N3 endoscop* S5 TI (PEG N3 tube* or PEG N3 feed* ) or AB (PEG N3 tube* or PEG N3 feed*) S4 TI percutaneous endoscopic gastrostom* or AB percutaneous endoscopic gastrostom* S3 S1 and S2 S2 TI percutaneous or AB percutaneous S1 (MH "Endoscopy, Gastrointestinal+")

Appendix 5. Risk of bias definitions

1. Was the allocation sequence randomly generated?

Low risk of bias

The investigators describe a random component in the sequence generation process such as: referring to a random number table; using a computer random number generator; coin tossing; shuffling cards or envelopes; throwing dice; drawing of lots.

High risk of bias

The investigators describe a non‐random component in the sequence generation process. Usually, the description would involve some systematic, non‐random approach, for example: sequence generated by odd or even date of birth; sequence generated by some rule based on date (or day) of admission; sequence generated by some rule based on hospital or clinic record number.

Unclear

Insufficient information about the sequence generation process to permit judgement of low or high risk of bias.

2. Was the treatment allocation adequately concealed?

Low risk of bias

Participants and investigators enrolling participants could not foresee assignment because one of the following, or an equivalent method, was used to conceal allocation: central allocation (including telephone, web‐based and pharmacy‐controlled randomisation); sequentially‐numbered drug containers of identical appearance; sequentially‐numbered, opaque, sealed envelopes.

High risk of bias

Participants or investigators enrolling participants could possibly foresee assignments and thus introduce selection bias, such as allocation based on: using an open random allocation schedule (e.g. a list of random numbers); assignment envelopes were used without appropriate safeguards (e.g. if envelopes were unsealed or non opaque or not sequentially numbered); alternation or rotation; date of birth; case record number; any other explicitly unconcealed procedure.

Unclear

Insufficient information to permit judgement of low or high risk of bias. This is usually the case if the method of concealment is not described or not described in sufficient detail to allow a definite judgement, for example if the use of assignment envelopes is described, but it remains unclear whether envelopes were sequentially numbered, opaque and sealed.

3. Blinding ‐ was knowledge of the allocated interventions adequately prevented during the study?

Low risk of bias

Any one of the following.

No blinding, but the review authors judge that the outcome and the outcome measurement are not likely to be influenced by lack of blinding.

Blinding of participants and key study personnel ensured, and unlikely that the blinding could have been broken.

Either participants or some key study personnel were not blinded, but outcome assessment was blinded and the non‐blinding of others unlikely to introduce bias.

High risk of bias

Any one of the following.

No blinding or incomplete blinding, and the outcome or outcome measurement is likely to be influenced by lack of blinding.

Blinding of key study participants and personnel attempted, but likely that the blinding could have been broken.

Either participants or some key study personnel were not blinded, and the non‐blinding of others likely to introduce bias.

Unclear

Any one of the following.

Insufficient information to permit judgement of low or high risk of bias.

The study did not address this outcome.

4. Were incomplete outcome data adequately addressed?

Low risk of bias

Any one of the following.

No missing outcome data.

Reasons for missing outcome data unlikely to be related to true outcome (for survival data, censoring unlikely to be introducing bias).

Missing outcome data balanced in numbers across intervention groups, with similar reasons for missing data across groups.

For dichotomous outcome data, the proportion of missing outcomes compared with observed event risk not enough to have a clinically relevant impact on the intervention effect estimate.

For continuous outcome data, plausible effect size (difference in means or standardised difference in means) among missing outcomes not enough to have a clinically relevant impact on observed effect size.

Missing data have been imputed using appropriate methods.

High risk of bias

Any one of the following.

Reason for missing outcome data likely to be related to true outcome, with either imbalance in numbers or reasons for missing data across intervention groups.

For dichotomous outcome data, the proportion of missing outcomes compared with observed event risk enough to induce clinically relevant bias in intervention effect estimate.

For continuous outcome data, plausible effect size (difference in means or standardised difference in means) among missing outcomes enough to induce clinically relevant bias in observed effect size.

‘As‐treated’ analysis done with substantial departure of the intervention received from that assigned at randomisation.

Potentially inappropriate application of simple imputation.

Unclear

Any one of the following.

Insufficient reporting of attrition/exclusions to permit judgement of low or high risk of bias (e.g. number randomised not stated, no reasons for missing data provided).

The study did not address this outcome.

5. Are reports of the study free of suggestion of selective outcome reporting?

Low risk of bias

Any of the following.

The study protocol is available and all of the study’s pre‐specified (primary and secondary) outcomes that are of interest in the review have been reported in the pre‐specified way.

The study protocol is not available but it is clear that the published reports include all expected outcomes, including those that were pre‐specified (convincing text of this nature may be uncommon)

High risk of bias

Any one of the following.

Not all of the study’s pre‐specified primary outcomes have been reported.

One or more primary outcomes is reported using measurements, analysis methods or subsets of the data (e.g. subscales) that were not pre‐specified.

One or more reported primary outcomes were not pre‐specified (unless clear justification for their reporting is provided, such as an unexpected adverse effect).

One or more outcomes of interest in the review are reported incompletely so that they cannot be entered in a meta‐analysis.

The study report fails to include results for a key outcome that would be expected to have been reported for such a study.

Unclear

Insufficient information to permit judgement of low or high risk of bias. It is likely that the majority of studies will fall into this category.

6. Other sources of potential bias

Low risk of bias

The study appears to be free of other sources of bias.

High risk of bias

There is at least one important risk of bias. For example, the study:

had a potential source of bias related to the specific study design used; or

has been claimed to have been fraudulent; or

had some other problem.

Unclear

There may be a risk of bias, but there is either:

insufficient information to assess whether an important risk of bias exists; or

insufficient rationale or evidence that an identified problem will introduce bias.

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Systemic antibiotic (IV) compared with placebo.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Peristomal infection | 8 | 586 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.34 [0.22, 0.53] |

Comparison 2. Systemic antibiotic (IV) compared with no intervention.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Peristomal infection | 3 | 623 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.30 [0.17, 0.53] |

Comparison 3. Systemic antibiotic (IV) compared with placebo/no intervention/skin antiseptic.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Peristomal infection | 12 | 1271 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.36 [0.26, 0.50] |

| 2 Allocation concealment | 12 | 1271 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.47 [0.34, 0.65] |

| 2.1 adequate allocation concealment | 8 | 554 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.58 [0.38, 0.88] |

| 2.2 unclear/inadequate concealment | 4 | 717 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.34 [0.21, 0.58] |

| 3 Sponsorship | 12 | 1271 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.36 [0.26, 0.50] |

| 3.1 Trials with no sponsorship | 10 | 962 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.38 [0.25, 0.56] |

| 3.2 Trials with sponsorship | 2 | 309 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.32 [0.18, 0.58] |

Comparison 4. Systemic antibiotic compared with systemic antibiotic.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Systemic antibiotic (IV) compared with systemic antibiotic (IV) | 1 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 1.1 Peristomal infection | 1 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 2 Systemic antibiotic (PEG) compared with systemic antibiotic (IV) | 1 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected |

Comparison 5. Systemic antibiotic (IV) compared with systemic antibiotic (IV) and skin antiseptic.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Peristomal infection | 1 | 68 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 15.78 [1.90, 130.86] |

Comparison 6. Skin antiseptic compared with systemic antibiotic (IV) and skin antiseptic.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Peristomal infection | 1 | 62 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 15.63 [1.84, 133.09] |

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Ahmad 2003.

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial. | |

| Participants | Male and female patients. Over 18 years. PEG tube inserted for CVA (n= 38) CNS disorders (n= 20), oropharyngeal cancer (n= 18) and miscellaneous (n= 26) (Taken from Table 1 ‐ 102 patients evaluable on a per protocol analysis). Excluded if no consent or suspected/confirmed allergy to antibiotic used. Total number of patients randomised; n = 141. | |

| Interventions | 'Pull' technique Group 1: cefuroxime 750 mg IV 30 min prior to PEG (n = 50); Group 2: saline placebo IV 30 min prior to PEG (n = 51); Group 3: receiving antibiotics before and during the study (n = 40). | |

| Outcomes | Peristomal infection. Complications. | |

| Notes | Group 3 excluded from analysis as not randomised.Used Jain et al criteria for wound assessment. Country of origin: Wales. Power calculation performed. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Predetermined computer‐generated randomisation scheme. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Review authors unable to contact study authors for clarification. |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) Blinding patient | Low risk | Patients received intravenous antibiotics or saline. |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) Blinding care provider | Low risk | Procedure by doctor or nurse not involved in the study. |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) Blinding outcome assessor | Low risk | Blinded to treatment group. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) Drop outs/withdrawals | Unclear risk | 8 (5.6%) of 141 patients excluded because of incomplete data. Comment: A 5.6% drop out rate makes the study at unclear risk of attrition bias. However the study reports 133 patients "were analysable on an intention to treat analysis". |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | Prespecified outcomes reported. |

| Baseline imbalance? (Was the study free of baseline imbalance?) | Low risk | Balanced for gender, age, reason for PEG, underlying conditions. |

| Timing of outcome assessment similar in all groups? | Low risk | In all groups outcomes were assessed immediately after procedure plus three, five and seven days. |

Akkersdijk 1995.

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial. | |

| Participants | Consecutive male and female patients. PEG tube inserted for oropharyngeal cancer (n= 56), neurological (n= 32) and other (n= 12). Inclusion and exclusion criteria not stated. Total number of patients randomised; n = 100. |

|

| Interventions | 'Pull' and 'push' techniques. Group 1: Pull, augmentin 1.2 g IV 3 doses given, 1st dose 30 min prior to procedure two doses administered over 24 hours (n = 37); Group 2: pull, no placebo, no antibiotic (n = 34); Group 3: push, no placebo, no antibiotic (n = 29). | |

| Outcomes | Peristomal infection. Major and minor complications. Comparison between push and pull technique. | |

| Notes | Criteria for wound assessment: minor infection present if redness with or without purulent discharge, major infection judged by physician as those requiring antibiotics. Country of origin: Netherlands. No power calculation performed. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not stated. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not stated. |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) Blinding patient | Unclear risk | Not stated; no placebo given. |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) Blinding care provider | Unclear risk | Not stated. |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) Blinding outcome assessor | Unclear risk | Not stated. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) Drop outs/withdrawals | Low risk | PEG placement failed in four patients (4%). |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | All prespecified outcomes reported. |

| Baseline imbalance? (Was the study free of baseline imbalance?) | Low risk | All groups were balanced for age, reason for PEG, underlying conditions. |

| Timing of outcome assessment similar in all groups? | Low risk | Outcomes assessed in all groups twice weekly for one month. |

Blomberg 2010.

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial | |

| Participants | Male and female patients. PEG tube inserted for ear, nose or throat cancer (127), neurological disease (42), oesophageal cancer (n= 30), stroke (n= 11), dementia (n= 1), gastric cancer (n= 1), and other (n= 22). Included if able to consent to participation in the study after receiving oral and written information or did not meet exclusion criteria and no contraindications for PEG. Excluded if ongoing antibiotic treatment, illness too severe to allow the patient to participate, allergy to any of the antibiotic alternatives. Total number of patients randomised; n = 234 |

|

| Interventions | Pull technique. Group 1: Co‐trimoxazole (800mg sulfamethoxazole &160mg trimethoprim) in 20ml deposited in the PEG immediately after insertion (n=116). Group 2: Cefuroxime 1.5g IV given 1 hour before PEG insertion (n= 118). | |

| Outcomes | Primary outcome ‐ wound infection Clinically evident peristomal infection at follow up appointment infection within 7‐ 14 days after insertion of the PEG catheter. Secondary outcomes ‐ Positive bacterial culture or blood biochemistry. |

|

| Notes | Criteria for wound assessment: a clinically identifiable wound infection, as judged by a red zone around the catheter or occurrence of pus, subcutaneous swelling, and pain on palpation in the area around the catheter. Secondary outcomes objective signs of infection, including a positive bacterial culture, high levels of highly sensitive C reactive protein, and a high white blood cell count. Country of origin: Sweden. Power calculation performed for non‐inferiority. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | "The randomisation process was conducted by personnel at a hospital department not engaged in the care of the included patients" "Personnel were contacted by telephone and on request opened a closed envelope, taken from a pre‐prepared block (50 envelopes in each block) of equally distributed and mixed envelopes, containing a randomisation sheet with information on the drug to be used" |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | "The randomisation process was conducted by personnel at a hospital department not engaged in the care of the included patients" "Personnel were contacted by telephone and on request opened a closed envelope, taken from a pre‐prepared block (50 envelopes in each block) of equally distributed and mixed envelopes, containing a randomisation sheet with information on the drug to be used" |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) Blinding patient | Low risk | "the blinding of the patients was accomplished by using intravenous fluid and manipulating the newly inserted PEG catheter in all patients. This sham manoeuvre was facilitated by the use of sedation" |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) Blinding care provider | Unclear risk | Not stated. |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) Blinding outcome assessor | Low risk | "The nurses who evaluated the patients at follow‐up visit were not involved in insertion of the PEG catheter, including the administration of antibiotics" |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) Drop outs/withdrawals | High risk | Out of 34 dropouts (14.5%) or withdrawals, a total of twelve participants in each group did not undergo PEG placement for anatomical reasons. Other attrition included five deaths, one patient pulled out PEG, three lost to follow‐up and one received co‐trimoxazole after being randomised to cefuroxime. Comment: 15% drop out rate makes the study at high risk of attrition bias, but ITT analysis undertaken. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | All prespecified outcomes reported. |

| Baseline imbalance? (Was the study free of baseline imbalance?) | Low risk | Both groups were balanced for age,smoking, diabetes, indications for PEG.Slight gender imbalance 42 females in group 1 versus 31 females in group 2. |

| Timing of outcome assessment similar in all groups? | Low risk | 7‐14 days for both groups. |

Dormann 2000.

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial. | |

| Participants | Male and female patients aged over 18 years requiring enteral feeding via PEG tube > six weeks. PEG tube inserted for neurological disease (n= 145), tumour (n= 63) and other (n= 8). (Taken from Table 1 ‐ 216 patients evaluable as 21 dropouts). Excluded if signs of infection, peritonitis ascites, peritoneal malignancy, prior gastric/bowel disease, granulocytopenia, previous radio/chemotherapy, antibiotic treatment within previous 72 h, clotting/platelet disorders, sensitivity to ceftriaxone. Total number of patients randomised; n = 237. |

|

| Interventions | 'Pull' technique:

Group 1: ceftriaxone 1 g IV 30 min prior to PEG (n = 106);

Group 2: no placebo, no antibiotic (n = 110). Numbers originally randomised into groups not given in trial report. |

|

| Outcomes | Peristomal infection. Mortality. Cost of antibiotic therapy. Post‐intervention antibiotic therapy. | |

| Notes | Used modified Jain et al criteria for wound assessment. Data from four previous studies incorporated into this study. Data from previous study (1999a), sponsored by Hoffman La Roche, incorporated into this study. Conducted in 12 secondary and tertiary medical centres. Country of origin: Germany. Power calculation performed. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Randomised in blocks of four using Rancode 3.1. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not stated. |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) Blinding patient | Unclear risk | Not stated. |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) Blinding care provider | Unclear risk | Not stated. |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) Blinding outcome assessor | Unclear risk | 'Study monitors' involved but specific role not stated. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) Drop outs/withdrawals | Low risk | 21 drop outs (8.9%). |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | Prespecified outcomes addressed. |

| Baseline imbalance? (Was the study free of baseline imbalance?) | Low risk | Both groups balanced for gender, age, reasons for PEG tube, BMI,indications for PEG, underlying conditions. |

| Timing of outcome assessment similar in all groups? | Low risk | Outcomes in both groups were assessed at one, two, four and ten days (mean 8.7). |

Gossner 1999.

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial. | |

| Participants | Male and female patients with proportionately more males (n = 243) than females (n = 93). PEG tube inserted for malignant disease (n= 210), neurological disorders (n= 97). (Taken from Table 1 ‐ 307 patients evaluable as 40 dropouts). Included if had functional resorption and digestive capacity with temporary, or permanent, dysphagia. Excluded if severe clotting or wound healing disorder, pronounced immune deficiency, paralytic ileus, Billroth II procedure, peritonitis, ascites, sensitive to antibiotics used. Total number of patients randomised; n = 347. |

|

| Interventions | Modified 'pull' technique.

Group 1: cefotaxime 2 g by infusion 30 min prior to PEG (n = 101);

Group 2: piperacillin 2 g + 0.5 g tazobactam by infusion (n = 100);

Group 3: no placebo, no antibiotic (n = 106).

Infusion given over 20 min. Numbers originally randomised into groups not given in trial report |

|

| Outcomes | Peristomal infection. Peritonitis. Mortality. | |

| Notes | Used Jain et al and Shapiro et al criteria for wound assessment. Included data from a previous study. Country of origin: Germany. No power calculation performed. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not stated. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | High risk | Randomly assigned to group after consent taken, and at least one day before procedure. |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) Blinding patient | Unclear risk | Not stated. |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) Blinding care provider | Unclear risk | Not stated. |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) Blinding outcome assessor | Unclear risk | Not stated. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) Drop outs/withdrawals | Low risk | 40 drop outs (11.5%). |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | Prespecified outcomes reported. |

| Baseline imbalance? (Was the study free of baseline imbalance?) | Low risk | All groups were balanced for age, gender, weight, Karnofksy index, reasons for PEG. |

| Timing of outcome assessment similar in all groups? | Low risk | Outcomes in all groups were assessed daily for seven days. Those discharged were assessed over the telephone or via the outpatient department, but the group was not specified. |

Jain 1987.

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial. | |

| Participants | Male and female patients (distribution not stated) who had given consent. PEG tube inserted for CVA (n= 53), oropharyngeal cancer (n= 27), CNS trauma (n= 8), CNS infection (n= 3), CNS degenerative disease (n= 10) and miscellaneous (n= 6). Excluded if: allergic to cefazolin, refused signed consent, technical reasons for PEG placement. Total number of patients randomised; n = 107. |

|

| Interventions | Technique not stated, but presumed to be 'pull' as the authors state 'the feeding tube traverses the mouth and pharynx'.

Group 1: receiving antibiotics before and during the study and were randomly assigned to:

Group 1 a: cefazolin 1 g IV 30 min prior to PEG (n = 25);

Group 1 b: saline placebo IV 30 min prior to PEG (n = 27); Group 2 not receiving antibiotics were randomly assigned to: Group 2 a: cefazolin 1 g IV 30 min prior to PEG (n = 27); Group 2 b: saline placebo IV 30 min prior to PEG (n = 28). |

|

| Outcomes | Peristomal infection. | |

| Notes | Criteria for wound assessment scoring devised by Jain et al which used indicators previously used by Shapiro et al (1982). Group 1 excluded from grouped analysis. Country of origin: USA. Power calculation performed. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Randomisation schedule generated by Hewlitt‐Packard HP‐67 pocket calculator. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | One author (KPC) was responsible for (and the only one aware of) assignment and did not evaluate the wounds. |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) Blinding patient | Low risk | Stated as 'double blind'. |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) Blinding care provider | Low risk | Stated as 'double blind'. |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) Blinding outcome assessor | Low risk | Outcomes assessed by team members blind to placebo allocation. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) Drop outs/withdrawals | Low risk | No drop outs. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | Prespecified outcomes addressed. |

| Baseline imbalance? (Was the study free of baseline imbalance?) | Unclear risk | All groups were balanced for gender, underlying conditions, reasons for PEG. In group 1 the mean age was slightly but significantly less than that of patients who did not receive prophylaxis. |

| Timing of outcome assessment similar in all groups? | Low risk | Outcomes in all groups were assessed daily for seven days. |

Jonas 1985.

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial. | |

| Participants | All male patients with dysphagia, consent, and functionally‐intact gastrointestinal tract. PEG tube inserted for underlying malignancy (n= 18) and neurological (n= 15). (Taken from Table 4 ‐ 33 patients evaluable as 4 dropouts). Excluded if had gastric ulcer/cancer, active infection requiring antibiotics, peritonitis, ascites, extensive abdominal surgery, contraindications to endoscopy, hypersensitivity to cephalosporins, or refused consent. Total number of patients randomised; n = 37. |

|

| Interventions | 'Pull' technique:

Group 1: cefoxitin 1 g IV 30 min prior to PEG (2 further doses given at 6 h intervals) (n = 17);